Dragan Novaković’s Club Row

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

These photographs of the Club Row animal and bird market were taken by Dragan Novaković in the late seventies – the market closed in 1983 when street trading in live animals became outlawed

Photographs copyright © Dragan Novaković

You also might like to take a look

In Old Haggerston

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

William Palin recalls the lost wonders of the once coherent and distinctive neighbourhood of Haggerston

Tudor Gothic Villas in Nichols Sq, 1945

Haggerston, in the Borough of Hackney, remains one of those ‘lost’ districts of London’s inner suburbs. Even the boundaries of this elusive locale have fluctuated, yet although the current electoral ward extends deep into Shoreditch, I would draw the borders of Haggerston at Hackney Rd to the south, Queensbridge Rd to the east, Kingsland Rd to the west and Regent’s Canal to the north.

Just a few important public buildings remain in Haggerston, including the old Haggerston Library – which was left to rot in the seventies before being facaded in the nineties – and the magnificent Haggerston Baths on Whiston St with its gilded Golden Hind weather vane. Poignant indicators of the glories that once were here.

Although Haggerston suffered some bomb damage – St Mary’s Church by John Nash was completely destroyed in 1941 – it was the post-war planners who erased most of the superior nineteenth century terraces, with streets of sound houses succumbing to the bulldozers as late as 1978. While the estates that replaced them may have provided superior accommodation and new amenities, they were brutal and uncompromising in their disregard for the intimacy, cohesion, humanity and community spirit of the old streets – attributes embraced in other similar London neighbourhoods wherever the terraces were retained.

As London’s population grew rapidly in the nineteenth century, Haggerston became a densely populated industrial suburb. In many eastern districts, land ownership tended to be fragmented, resulting in a series of relatively small-scale building speculations that eventually came together to form a coherent if quirky network of streets with pubs, shops and small industry, all adding to the diverse character of the streetscape. Although individual speculators – whether a few houses or a whole street – imposed a uniformity of design, there was surprising and delightful variation between streets with even modest houses exhibiting decorative flourishes in their brickwork, fanlights, shutters and front doors. Where streets met, the junctions were resolved with an effortless dexterity which was one of the striking characteristics of the London speculative builder and, on the rare occasion a pub was absent, a corner house was built with a side entrance.

In common with most of south Hackney and Shoreditch, the dominant industries of the area were the furniture and finishing trades. An insurance map of 1930 shows timber yards, French polishers, enamellers, cabinet factories, mirror frame factories, wood carvers and a plethora of other related trades. Interestingly, the legacy of these industries is still evident today in the Hackney Rd, where Maurice Franklin the ninety-three year old wood turner works at The Spindle Shop and D.J.Simons maintain their thriving business supplying mouldings for picture framing after more than a century, as well as in the handful of second hand shops trading in the furniture once made locally.

Unquestionably, the centrepiece of Haggerston’s nineteenth century development was Nichols Sq, situated east of the Geffrye Museum beyond the railway viaduct. Built in 1841 and featuring two outward facing rows of picturesque Tudor gothic villas at its centre, Nichols Sq was further enhanced in 1867-9 by a splendid church and vicarage – St Chad’s – by the architect James Brooks. Surviving in good condition until blighted by a Compulsory Purchase Order, the square was swept away in 1963 for the Fellows Court Estate. Geoffrey Fletcher, author of ‘The London Nobody Knows,’ lamented the impending loss in 1962 by illustrating the houses in the Daily Telegraph, and describing “the delightful Gothic villas … in excellent condition [which] if they were in Chelsea would fetch anything from £10,000 to £15,000.” Savouring the architectural detail, he comments “Typical of the finesse of the period is that, while the terrace railings have a Classic flavour, the similar ones of the cottages have a Tudor outline. But after next year none of this will matter any more.”

The London County Council planning files record no evidence of any robust defence of Nichols Sq. The principal concern – ironic in the context of the current plans to demolish the Marquis of Lansdowne pub – was the effect of the new tower blocks upon the setting of the Geffrye Museum. Nichols Sq had only one entrance, which led from Hackney Rd at the south east corner, and this was guarded by a Tudor lodge. The secluded location had helped it retain an isolated respectability until the very end, despite the incursion of the railway viaduct across its western extremity just a few years after completion.

To the south of Fellows Court Estate is Cremer St, the only direct link between Hackney Rd and Kingsland Rd, which was once graced by a series of modest but elegant semi-detached villas (a building type that became a defining characteristic of Hackney). These villas are captured in a beautiful series of LCC photographs of 1946, which also show a double-fronted detached house with a wide fanlight, where an old man perches on the high front steps, lighting a pipe. In Cremer St, The Flying Scud pub, with its distinctive blue Truman’s livery survived until only a few years ago, while running south from there – now reached via a rubbish-strewn alley – is Long St, whose distinctive yellow brick houses are also illustrated in the LLC old photographs. Of these, only a few paving stones survive.

To the north of the Fellows Court Estate is Dunloe Street, once lined by neat terraces, now bleak save for St Chad’s Church – the last fragment of Nichols Sq. Dunloe St linked into a network of small streets, including Appleby St and Ormsby St, where well-maintained and well-loved terraces endured until 1978 when they were controversially emptied of their occupants and demolished. A handful of houses on the west end of Pearson St are now the only reminders we have of this once vibrant and homogenous neighbourhood.

In 1966, architectural critic Ian Nairn spoke eloquently of the lost opportunities of the rebuilding of the East End, in words that perfectly describe the fate of old Haggerston – “All the raucous, homely places go and are replaced by well-designed estates which would fit a New Town but are hopelessly out of place here. This is a hive of individualists, and the last place to be subjected to this kind of large-scale planning. Fragments survive, and the East Enders are irrepressible …but they could have had so much more, so easily.”

Nichols Sq by Geoffrey Fletcher, 1963

Plan and perspective of Nichols Sq, 1845 – not really a square at all but highly picturesque. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

North side of Nichols Sq, 1960.

Washing the doorstep in Shap St with the Fellows Court Estate beyond, 1974. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

A rich and coherent cityscape – Shap St, looking north, 1974. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

Elegant dark-painted sashes and immaculately maintained shutters in Ormsby St, 1965. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

Hows St, c.1960. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

Whiston St in the hot summer of 1976, just before demolition. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

Intimate streetscape – Ormsby St, 1965. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

Weymouth Terrace shortly before demolition, 1964. Note the stuccoed ground floor facade. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

Geffrye St, 1960s (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

“All the homely places have gone”– Sitting room at 50 Shap St c.1959. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

Fellows Rd, 1959. Neat terraces with blank panels at parapet level. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

A perfect corner, courtesy of the London speculative builder. Pearson St and Fellows St, 1951. (Copyright Hackney Archives Department)

Ormsby St before demolition, 1978 – note the photographer’s blackboard on the window ledge. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Cremer St, 1946. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Cremer St, 1946. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Detail – Man lights a pipe in Cremer St, 1946. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Cremer St, 1946. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Tudor Gothic villas in Nichols Sq, 1950. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Tudor Gothic villas in Nichols Sq with fleur de lis railings, 1950. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Iain Nairn described the East End as “a hive of individualists” – this applied to the builders too, as shown in the delightfully quirky design of these houses in Long St, photographed in 1951. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

Fine eighteenth century doorcase at 171 Kingsland Road. The house and its neighbours came down in the late sixties. (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives)

A Gift From Libby Hall

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

Five Christmases ago, I received the most extraordinary present I ever expect to receive. It is Charles Dickens’ inkwell.

In the week before Christmas, I paid a seasonal visit to photographer & collector Libby Hall in Clapton and, as we sat there beside a table groaning with festive treats, she handed me a parcel with the words, ‘I thought you should have this.’ It is a phrase often used when gifts are presented but it was only when I unwrapped it that I discovered the true meaning of her words. What better gift could there be for a writer than an inkwell that once belonged to Charles Dickens?

It is a small travelling inkwell which screws shut and that a writer might easily carry in a pocket or bag, as Dickens did with this one when he visited America in 1842 and left it behind. Barely larger than a pocket watch, it is a modest utilitarian item comprising a square glass bottle and a hinged brass top with a screw fixture to hold it shut. What distinguishes this specimen are the initials engraved on the lid in tentative gothic capitals, C.D.

Libby told me that it was a gift from her friend Cinda in New York whose father had been given it in 1949/50 by a Dr Rhodebeck. All Cinda can remember is that the Rhodebecks were a long-established family in Manhattan who lived in Park Avenue near 86th St. She understood they had been custodians of the inkwell since the eighteen-forties.

Charles Dickens’ first visit to America, which he described in his American Notes, proved a great source of disappointment to the young writer. Although his books were bestsellers and he received universal adulation, there was no law of copyright and he earned no income whatsoever from his sales there. He arrived with an idealistic view of America, imagining a democratic, progressive society without the handicap of decayed old-world aristocracy. What he discovered was the brutal reality of slavery, inhuman prisons and rampant gangsterism.

It was also the first time that Dickens encountered the full wattage of his own celebrity, forced to flee through the streets of Manhattan with crowds of over-enthusiastic fans in pursuit. Yet he rose to the occasion by acquiring an ostentatious wardrobe of new outfits, even if he was spooked by the fanaticism of those who wanted to steal the fluff from his coat as souvenirs.

This raises the question whether Dickens mislaid the inkwell or whether it was appropriated? A chip on the top left corner of the bottle suggests it might have been dropped and then discarded. The wing-nut which secures the lid is missing too and the brass top has come adrift, perhaps indicating that the inkwell was damaged and was no longer considered of use? At this time in his career, Dickens used black iron gall ink which is a corrosive, explaining why the metal top came off the bottle.

Seeking further information about the inkwell, I took it along to the Charles Dickens Museum in Doughty St where curator Louisa Price agreed to take a look and she confirmed that it is an inkwell of the correct period. We searched the Collected Letters and back numbers of the Dickensian to no avail for any mentions of a lost inkwell in America or the Rhodebeck family. Then Louisa brought out a selection of engraved personal items belonging to Dickens from this era for comparison and we could see that he preferred his initials in gothic capitals over the roman or cursive alternatives that would have been available.

The most persuasive evidence was an inkwell from Dickens writing box which once sat upon his desk. Less utilitarian than the travelling version, this example nevertheless had an almost identical bottle in size and design, and although the large brass screw top was more elaborate, including his symbol of the lion recumbent, the gothic capitals were similar to those on the travelling inkwell.

Louisa Price concluded that the inkwell feels right and there is no evidence to suggest it is not authentic, but it would be helpful to uncover evidence linking Charles Dickens and the Rhodebeck family. So this is where I need your help, dear readers. I know that many of you are researchers and some of you are in America. Can anyone tell me more about the Rhodebecks or find any literary connections which might link them to Charles Dickens and establish the provenance of the inkwell?

UPDATE

With thanks to Linda Granfield & Theresa Musgrove for locating Dr Rhodebeck

Dr. Edmund Jean Rhodebeck, b. 1894 had an office at 1040 Park Ave (near 86th St) and a residential address nearby at 1361 Madison Ave. He was a collector of literary materials, including a copy of The Works of William D’Avenant with Herman Melville marginalia. He also wrote an article about Kateri Takakwitha, a Mohawk woman considered for sainthood, for a 1963 newsletter. His father was Frederick, born in the 1860s and his grandfather was a Peter Rhodebeck, born c. 1830 who worked as a saloon keeper on Broadway c 1880, but in New York directories for 1867 and 1868 is listed as a ‘driver’ at 124 West First Avenue and then West 49th St.

Can anyone tell us more about Dr Rhodebeck and his literary collection?

Dr Edmund Rhodebeck, former owner of the inkwell

Charles Dickens’ inkwell sits upon my desk

Comparative photograph showing an inkwell from Dickens’ writing box in the collection of the Dickens House Museum on the left and the travelling inkwell on the right. Note similarity of the glass bottles and the gothic capitals. (Writing box inkwell reproduced courtesy of Charles Dickens Museum)

Charles Dicken in 1838 (Reproduced courtesy of National Portrait Gallery)

Dickens’ calling card as a young man (Reproduced courtesy of Dan Calinescu)

You may also like to read about

Charles Dickens in Spitalfields

Libby Hall’s Outtakes

Click here to book for my tours through July, August and September

When Libby Hall (1941-2023) was a press photographer in the sixties, based in Clerkenwell and travelling back and forth from her home in Clapton, she occasionally photographed her immediate surroundings as a diversion from her daily work. Yet half a century later these almost inconsequential outtakes have transformed into a powerful evocation of a lost era.

Libby Hall’s desk In Farringdon Rd

‘These photographs were mostly just lens tests, or moments of light that appealed to me on my journeys back and forth to work as a press photographer. The bookstalls were immediately across the street from the newspaper I worked for. I do miss those wonderful bookstalls even though they used up a considerable chunk of my then meagre wages. It was impossible to pass by without having a look – but then what treasures there were to be found!’ – Libby Hall

Looking down onto Farringdon Rd

Looking across to Turnmills St, Clerkenwell Session House and Booth’s Gin Distillery

Bookstalls in Farringdon Rd

Farringdon Station

Liverpool St Station

Clapton Station

Photographs copyright © Estate of Libby Hall

You may also like to take a look at

Libby Hall’s London Dogs

Tickets are available for my tours throughout July, August & September

Commemorating Libby Hall (1941-2023), Photographer & Collector of Dog Photography

Click to enlarge

Sometimes in London, I think I hear a lone dog barking in the distance and I wonder if it is an echo from another street or a yard. Sometimes in London, I wake late in the night and hear a dog calling out to me on the wind, in the dark silent city of my dreaming. What is this yelp I believe I hear in London, dis-embodied and far away? Is it the sound of the dogs of old London – the guard dogs, the lap dogs, the stray dogs, the police dogs, the performing dogs, the dogs of the blind, the dogs of the ratcatchers, the dogs of the watermen, the cadaver dogs, the mutts, the mongrels, the curs, the hounds and the puppies?

Libby Hall, who gathered possibly the largest collection of dog photography ever made by any single individual, helped me select the dogs of old London from her personal archive. We pulled out those from London photographic studios and those labelled as London. Then, Libby also picked out those that she believed are London. And here you see the photographs we chose. How eager and yet how soulful are these metropolitan dogs of yesteryear. They were not camera shy.

The complete social range is present in this selection, from the dogs of the workplace to the dogs of the boudoir, although inevitably the majority are those whose owners had the disposable income for studio portraits. These pictures reveal that while human fashions change according to the era and the class, dogs exist in an eternal present tense. Even if they are the dogs of old London and even if in our own age we pay more attention to breeds, any of these dogs could have been photographed yesterday. And the quality of emotion these creatures drew from their owners is such that the people in the pictures are brought closer to us. They might otherwise withhold their feelings or retreat behind studio poses but, because of their relationships with their dogs, we can can recognise our common humanity more readily.

These pictures were once cherished by the owners after their dogs had died but now all the owners have died too, long ago. For the most part, we do not know the names of the subjects, either canine or human. All we are left with are these poignant records of tender emotion, intimate lost moments in the history of our city.

The dogs of old London no longer cock their legs at the trees, lamps and street corners of our ancient capital, no longer pull their owners along the pavement, no longer stretch out in front of the fire, no longer keep the neighbours awake barking all night, no longer doze in the sun, no longer sit up and beg, no longer bury bones, no longer fetch sticks, no longer gobble their dinners, no longer piss in the clean laundry, no longer play dead or jump for a treats. The dogs of old London are silent now.

Arthur Lee, Muswell Hill, inscribed “To Ruby with love from Crystal.”

Ellen Terry was renowned for her love of dogs as much as for her acting.

W.Pearce, 422 Lewisham High St.

This girl and her dog were photographed many times for cards and are believed to be the photographer’s daughter and her pet.

Emberson – Wimbledon, Surbiton & Tooting.

Edward VII’s dog Caesar that followed the funeral procession and became a national hero.

A prizewinner, surrounded by trophies and dripping with awards.

The Vicar of Leyton and his dog.

The first dog to be buried here was run over outside the gatekeeper’s lodge, setting a fashionable precedent, and within twenty-five years the gatekeeper’s garden was filled with over three hundred upper class pets.

Libby Hall, collector of dog photographs.

Photographs copyright © The Libby Hall Collection at the Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read my profile

So Long, Libby Hall

Libby Hall (1941-2023), Photographer & Collector of Dog Photography, died last Thursday

Libby Hall

Between 1966 and 2006, Libby Hall collected old photographs of dogs, amassing many thousands to assemble what is possibly the largest number of canine pictures ever gathered by any single person. Libby began collecting casually when the photographs were of negligible value, but by the end she had published four books and been priced out of the market. Yet through her actions Libby rescued an entire canon of photography from the scrap heap, seeing the poetry and sophistication in images that were previously dismissed as merely sentimental. And today, we are the beneficiaries of her visionary endeavour.

A joyful iconoclast by nature who had, “Stop! Do not resuscitate, living will extant,” tattooed on her chest – Libby Hall was a born and bred New Yorker originating from the Upper East Side of Manhattan, who moved into her house in Clapton in 1967 with her husband the newspaper cartoonist, Tony Hall, and stayed for the rest of her life.

“My husband Tony and I used to go to Kingsland Waste, where we had a friend who did house clearances, and in those days they sold old photo albums and threw away the pictures. So I used to rescue them and I began sorting out the dogs – because I always liked dogs – and it became a collection. Then I started collecting properly, looking for them at car boot sales and auctions. And eventually a publisher offered me an advance of two thousand pounds for a book of them, which was fantastic, and when each of my books was published I just used the royalties to buy more and more photographs. I had a network of dealers looking out for things for me and they would send me pictures on approval. They were nineteenth century mostly and I only collected up until 1940, because I didn’t want to invade anyone’s privacy. Noboby was interested until my first book was published in 2000, and afterwards people said I had shot myself in the foot because everybody started collecting them and they became very expensive, but by then I had between five and six thousand photographs of dogs.

Dogs have always been powerfully important to me, I’ve lived with dogs since the beginning of my days. There’s a photo of my father holding me as baby in one arm and a dog in the other – dog’s faces were imprinted upon my consciousness as early as humans, and I’ve always lived with dogs until six weeks ago when my dog Pembury died. For the last month, friends have been ringing my bell and there’s only silence because he doesn’t come and I open the door to find them in tears. It was an intense relationship because it was just the two of us, Pembury and me, and as he got older he depended on me greatly. So it is good to have my freedom now but only for a little while. At one point, we had three dogs and four cats in this house. We even had a dog and a cat that used to sleep together, during the day they’d do all the usual challenging and chasing but at night they’d curl up in a basket.

When I was eleven, I wanted a dog of my own desperately, I’d been campaigning for five years and I wanted a cocker spaniel. My father contacted a dog rescue shelter in Chester, Connecticut, and they said they had one. But as we walked past the chain link fence, there was a dog barking and we were told that it was going to be put down the next morning. Of course, we took that dog, even though he wasn’t a cocker spaniel. We wondered if they always told people this, but Chester and I were inseparable ever after.”

With touching generosity of spirit, Libby confided to me that her greatest delight is to share her collection of pictures. “What matters to me is others seeing them, I never made any money from my books because I spent it all on buying more photographs.” she said.

These photographs grow ever more compelling upon contemplation because there is always a tension between the dog and the human in each picture. The presence of the animal can unlock the emotional quality of people who might otherwise appear withheld, and the evocation of such intimacy in pictures of the long dead, who are mostly un-named, carries a soulful poetry that is all its own. Bridging the gap of time in a way that photographs solely of humans do not, Libby’s extraordinary collection constitutes an extended mediation upon mortality and the fragility of tender emotions.

“I put my heart and soul into it, and it was very hard giving up collecting, but my fourth book was the ultimate book, and it coincided with the realisation that my husband Tony was dying, so I realised that it was the end of a period of my life.” Libby concluded with a melancholy smile, sitting upon the couch where her dog Pembury had recently expired and casting her eyes thoughtfully around the pictures of dogs lining the walls. I asked Libby how she felt after she donated her collection to the Bishopsgate Institute. “I’ve got the books,” she reminded me, placing her hand upon them protectively, “I have no visual memory at all, so I keep going back to look at them.”

The two stripes on this soldier’s sleeve meant he had been wounded twice and was probably on leave recovering from the second wound when this photograph was taken.

HRH the Princess of Wales with her favourite dogs on board the royal yacht Osborne.

John Brown 1871. The dogs are Corran, Dacho, Rochie and Sharp, who was Queen Victoria’s favourite.

George Alexander, Actor/Manager, with his wife Florence.

This photograph of Mick came with the collar he is wearing.

Queen Victoria and Sharp (pictured above with John Brown) at Balmoral in 1867.

Ellen Terry.

Charles Dickens with his devoted dog Turk.

Libby’s recently deceased dog Pembury wearing the vest that was essential in his last days.

Libby on the couch where Pembury died six weeks earlier.

One of Libby’s six dog dolls’ houses. – “I think dolls’ houses with dolls are rather scary but dolls’ houses with dogs are ok.”

Libby Hall – “I put my heart and soul into it.”

Portraits of Libby Hall copyright © Martin Usborne

Dog photographs copyright © The Libby Hall Collection at the Bishopsgate Institute

Charles Jones, Photographer

Tickets are available for my tour throughout July, August & September

Garden scene with photographer’s cloth backdrop c.1900

These beautiful photographs are all that exist to speak of the life of Charles Jones. Very little is known of the events and tenor of his existence, and even the survival of these pictures was left to chance, but now they ensure him posthumous status as one of the great plant photographers. When he died in Lincolnshire in 1959, aged 92, without claiming his pension for many years and in a house without running water or electricity, almost no-one was aware that he was a photographer. And he would be completely forgotten now, if not for the fortuitous discovery made twenty-two years later at Bermondsey Market, of a box of hundreds of his golden-toned gelatin silver prints made from glass plate negatives.

Born in 1866 in Wolverhampton, Jones was an exceptionally gifted professional gardener who worked upon several private estates, most notably Ote Hall near Burgess Hill in Sussex, where his talent received the attention of The Gardener’s Chronicle of 20th September 1905.

“The present gardener, Charles Jones, has had a large share in the modelling of the gardens as they now appear, for on all sides can be seen evidence of his work in the making of flowerbeds and borders and in the planting of fruit trees. Mr Jones is quite an enthusiastic fruit grower and his delight in his well-trained trees was readily apparent…. The lack of extensive glasshouses is no deterrent to Mr Jones in producing supplies of choice fruit and flowers… By the help of wind screens, he has converted warm nooks into suitable places for the growing of tender subjects and with the aid of a few unheated frames produces a goodly supply. Thus is the resourcefulness of the ingenious gardener who has not an unlimited supply of the best appurtenances seen.”

The mystery is how Jones produced such a huge body of photography and developed his distinctive aesthetic in complete isolation. The quality of the prints and notation suggests that he regarded himself as a serious photographer although there is no evidence that he ever published or exhibited his work. A sole advert in Popular Gardening exists offering to photograph people’s gardens for half a crown, suggesting wider ambitions, yet whether anyone took him up on the offer we do not know. Jones’ grandchildren recall that, in old age, he used his own glass plates as cloches to protect his seedlings against frost – which may explain why no negatives have survived.

There is a spare quality and an uncluttered aesthetic in Jones’ images that permits them to appear contemporary a hundred years after they were taken, while the intense focus upon the minutiae of these specimens reveals both Jones’ close knowledge of his own produce and his pride as a gardener in recording his creations. Charles Jones’ sensibility, delighting in the bounty of nature and the beauty of plant forms, and fascinated with variance in growth, is one that any gardener or cook will appreciate.

Swede Green Top

Bean Runner

Stokesia Cyanea

Turnip Green Globe

Bean Longpod

Potato Midlothian Early

Pea Rival

Onion Brown Globe

Cucumber Ridge

Mangold Yellow Globe

Bean (Dwarf) Ne Plus Ultra

Mangold Red Tankard

Seedpods on the head of a Standard Rose

Ornamental Gourd

Bean Runner

Apple Gateshead Codlin

Captain Hayward

Larry’s Perfection

Pear Beurré Diel

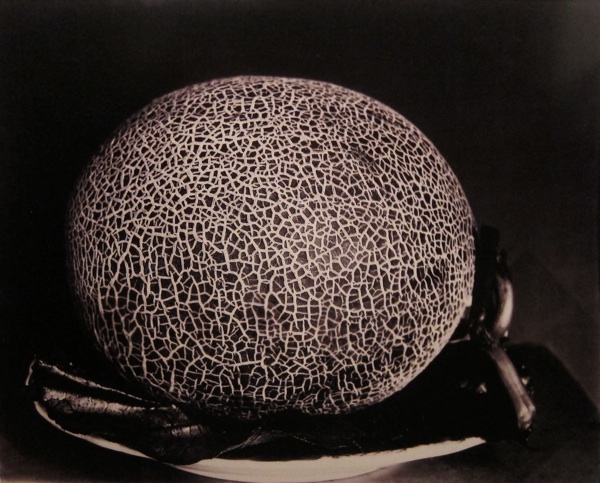

Melon Sutton’s Superlative

Mangold Green Top

Charles Harry Jones (1866-1959) c. 1904

The Plant Kingdoms of Charles Jones by Sean Sexton & Robert Flynn Johnson is published by Thames & Hudson

You might also like to read about

The Secret Gardens of Spitalfields

Thomas Fairchild, Gardener of Hoxton

Buying Vegetables for Leila’s Shop