At James Ince & Sons, Umbrella Makers

Click here to book for tour through September and October

Richard Ince, 11th generation umbrella maker

The factory of James Ince & Sons, the oldest established umbrella makers in the country, is one of the few places in London where you will not hear complaints about the rainy weather, because – while our moist climate is such a disappointment to the population in general – it has happily sustained generations of Inces for over two centuries now. If you walked down Whites Row in Spitalfields in 1824, you would have found William Ince making umbrellas and, six generations later, I was able to visit Richard Ince, still making umbrellas in the East End. Yet although the date of origin of the company is conservatively set at 1805, there was a William Inch, a tailor listed in Spitalfields in 1793, who may have been father to William Ince of Whites Row – which makes it credible to surmise that Inces have been making umbrellas since they first became popular at the end of the eighteenth century.

You might assume that the weight of so much history weighs heavily upon Richard Ince, but it is like water off a duck’s back to him, because he is simply too busy manufacturing umbrellas. Richard’s father and grandfather were managers with a large staff of employees, but Richard is one of only a handful of workers at James Ince & Sons today, and he works alongside his colleagues as one of the team, cutting and stitching, personally supervising all the orders. Watching them at work, it was a glimpse of what William Ince’s workshop might have been like in Spitalfields in 1824, because – although synthetics and steel have replaced silk and whalebone, and all stitching is done by machine now – the essential design and manufacturing process of umbrellas remains the same.

Between these two workshops of William Ince in 1824 and Richard Ince in 2011, exists a majestic history, which might be best described as one of gracious expansion and then sudden contraction, in the manner of an umbrella itself. It was the necessity of silk that made Spitalfields the natural home for James Ince & Sons. The company prospered there during the expansion of London through the nineteenth century and the increase in colonial trade, especially to India and Burma. In 1837, they moved into larger premises in Brushfield St and, by 1857, filled a building on Bishopsgate too. In the twentieth century, workers at Inces’ factory in Spitalfields took cover in the basement during air raids, and then emerged to resume making military umbrellas for soldiers in the trenches during the First World War and canvas covers for guns during the Second World War. Luckily, the factory itself narrowly survived a flying bomb, permitting the company to enjoy post-war success, diversifying into angling umbrellas, golfing umbrellas, sun umbrellas and promotional umbrellas, even a ceremonial umbrella for a Nigerian Chief. But in the nineteen eighties, a change in tax law, meaning that umbrella makers could no longer be classed as self-employed, challenged the viability of the company, causing James Ince & Sons to shed most of the staff and move to smaller premises in Hackney.

This is some of the history that Richard Ince does not think about very much, whilst deeply engaged through every working hour with the elegant contrivance of making umbrellas. In the twenty-first century, James Ince & Sons fashion the umbrellas for Rubeus Hagrid and for Mary Poppins, surely the most famous brollies on the planet. A fact which permits Richard a small, yet justly deserved, smile of satisfaction as the proper outcome of more than two hundred years of umbrella making by seven generations of his family. A smile that in its quiet intensity reveals his passion for his calling. “My father didn’t want to do it,” he admitted with a grin of regret, “but I left school at seventeen and I felt my way in. I used to spend my Saturdays in Spitalfields, kicking cabbages around as footballs, and when we had the big tax problem, it taught me that I had to get involved.” This was how Richard oversaw the transformation of his company to become the lean operation it is today. “We are the only people who are prepared to look at making weird umbrellas, when they want strange ones for film and theatre.” he confessed with yet another modest smile, as if this indication of his expertise were a mere admission of amiable gullibility.

On the ground floor of his factory in Vyner St, is a long block where Richard unfurls the rolls of fabric and cuts the umbrella panels using a wooden pattern and a sharp knife. Then he carries the armful of pieces upstairs where they are sewn together before Job Forster takes them and does the “tipping,” consisting of fixing the “points” (which attach the cover to the ends of the ribs), sewing the cover to the frame and adding the tie which is used to furl the umbrella when not in use.

Job was making huge umbrellas, as used by the doormen to shepherd guests through the rain, and I watched as he clamped the bare metal frame to the bench, revolving it as he stitched the cover to each rib in turn, to complete the umbrella. Then came the moment when Job opened it up to scrutinise his handiwork. With a satisfying “thunk,” the black cover expanded like a giant bat stretching its wings taut and I was spellbound by the drama of the moment – because now I understood what it takes to make one, I was seeing an umbrella for the first time, thanks to James Ince & Sons (Umbrella Makers) Ltd.

Richard Ince, seventh generation umbrella maker, prepares to cut covers for brollies.

Job Forster sews the cover to the ribs of the umbrella.

James Ince, born 1816

James John Ince, born 1830

Samuel George Ince, born 1853

Ernest Edward Sears, born 1870

Wilfred Sears Ince, born 1894

Geoffrey Ince, born 1932

Richard Ince, “Prepare for a rainy day!”

New photographs copyright © Chris Hill-Scott

Archive photographs copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

On Night Patrol With Constable Tassell

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

We join Constable Lew Tassell on a night patrol in the City of London on Tuesday December 12th 1972

Police Constable Lew Tassell of the City of London Police

“One week in December 1972, I was on night duty. Normally, I would be on beat patrol from Bishopsgate Police Station between 11pm-7am. But that week I was on the utility van which operated between 10pm-6am, so there would be cover during the changeover times for the three City of London Police divisions – Bishopsgate, Wood St and Snow Hill. One constable from each division would be on the van with a sergeant and a driver from the garage.

That night, I was dropped off on the Embankment during a break to allow me to take some photographs and I walked back to Wood St Police Station to rejoin the van crew. You can follow the route in my photographs.

The City of London at night was a peaceful place to walk, apart from the parts that operated twenty-four hours a day – the newspaper printshops in Fleet Street, Smithfield Meat Market, Billingsgate Fish Market and Spitalfields Fruit & Vegetable Market.

Micks Cafe in Fleet St never had an apostrophe on the sign or acute accent on the ‘e.’ It was a cramped greasy spoon that opened twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. During the night and early morning it served print-workers, drunks returning from the West End and the occasional vagrant.

Generally, we police did not use it. We might have been unwelcome because we would have stood out like a sore thumb. But I did observation in there in plain clothes sometimes. Micks Cafe was a place where virtually anything could be sourced, especially at night when nowhere else was open.”

Middle Temple Lane

Pump Court, Temple

King’s Bench Walk, Temple

Bouverie St, News of the World and The Sun

Fleet St looking East towards Ludgate Circus

Ludgate Hill looking towards Fleet St under Blackfriars Railway Bridge, demolished in 1990

Old Bailey from Newgate St looking south

Looking north from Newgate St along Giltspur St, St Bartholomew’s Hospital

Newgate St looking towards junction of Cheapside and New Change – buildings now demolished

Cheapside looking east from the corner of Wood St towards St Mary Le Bow and the Bank

HMS Chrysanthemum, Embankment

Constable Lew Tassell, 1972

Photographs copyright © Lew Tassell

You may also like to take a look at

A Walk Along The Ridgeway

Tickets available next Saturday 2nd September

They say it is the oldest road in Britain, maybe the oldest in Europe. Starting from the highest navigable point of the Thames in prehistoric times, the Ridgeway follows the hilltops to arrive at Salisbury Plain where once wild cattle and horses roamed. When the valleys were forested and impenetrable, the Ridgeway offered a natural route over the downland and into the heart of this island. Centuries of cattle driving wore a trackway that curved across the hillside, traversing the contours of the landscape and unravelling like a ribbon towards the horizon.

Over thousands of years, the Ridgeway became a trading route extending from coast to coast, as far as Lyme Regis in the west and the Wash in the east, with fortresses and monuments along the way. Yet once the valleys became accessible it was defunct, replaced by the Icknield Way – a lower level path that skirted the foot of the hills – and there are burial mounds which traverse the Ridgeway dated to 2000BC, indicating that the highway was no longer in use by then.

In fact, this obsolescence preserved the Ridgeway because it was never incorporated into the modern road network and remains a green path to this day where anyone can set out and walk in the footsteps of our earliest predecessors in this land. Leaving Spitalfields early and taking the hour’s rail journey to Goring & Streatley from Paddington, I was ascending the hill from the river by eleven and onto the upland by midday. In this section, the flinty path of the Ridgeway is bordered with deep hedges of hawthorn, blackthorn and hazel, giving way to the open downland rich with the pink and blue flowers of late summer, knapweed, scabious and harebells.

A quarter of a century has passed since I first passed this way and yet nothing has changed up there. It is the same huge sky and expansive grassy plain undulating into the distance with barely a building in sight. This landscape dwarfs the human figure, inducing a sense of exhilaration at the dramatic effects of light and cloud, sending patterns travelling fast across the vast grassy wind-blown hills. When I first began to write and London grew claustrophobic, I often undertook this walk through the different seasons of the year. I discovered that the sheer exertion of walking all day, buffeted upon the hilltops and sometimes marching doggedly through driving rain, never failed to clear my mind.

As a consequence, the shape of the journey is graven into memory even though, returning eighteen years since my last visit, the landscape was greater than I had fashioned it in recollection. And this is the quality that fascinates me about such epic terrain, which the mind cannot satisfactorily contain and thus each return offers a renewed acquaintance of wonder at the scale and majesty of the natural world.

In those days, I was in thrall to endurance walking and I would continue until I could go no further, either because of exhaustion or nightfall. This vast elevated downland landscape encouraged such excessive behaviour, leading me on and on along the empty path to discover what lay over the brow and engendering a giddy sense of falling forward, walking through the sky – as if you might take flight. I walked until I thought I could walk no more and then I carried on walking until walking became automatic, like breathing. In this state my body was propelled forward of its own volition and my mind was free.

One day’s walk brings you to Uffington and the famous White Horse, carved into the chalk of the downland. Placed perfectly upon the crest of a ridge within a vast fold of the hills, this sparsely drawn Neolithic figure looks out across the arable farmland of Oxfordshire beyond and can be seen for great distances. A mystery now, a representation that may once have been a symbol for a people lost in time, it retains a primeval charisma, and there is such an intensity of delight to reach this figure at the end of a day’s walking. Breathless and weary of limbs, I stumbled over the hill to sit there alone upon the back of the hundred foot White Horse at dusk, before descending to the village of Bishopstone for the night. There, at Prebendal Farm, Jo Selbourne offers a generous welcome and, as well as the usual bed and breakfast, will show you the exquisitely smoothed ceremonial Neolithic axe head found upon the farm.

The second day’s walk leads through the earthen ramparts of Liddington Hill and Barbary Castle, and on either side of the path the fields are punctuated by clumps of trees indicating the myriad ancient burial mounds scattered upon this bare Wiltshire scenery. It is a more expansive land than the fields of Berkshire where I began my journey, here the interventions made in ancient times still hold their own and the evidence of the modernity is sparser. As I made the final descent from the hill towards Avebury, a village within a massive earthwork and stone circle which was the culmination of my journey, I could not resist the feeling that it was all there for me and I had earned it by walking along the old path which for thousands of years had brought people to arrive at this enigmatic location of pilgrimage.

In two days upon the hilltops I had only passed a dozen lone walkers, and now the crowds, the coach parties, the shops and the traffic were a startling sight to behold. And so I knew my journey had fulfilled its purpose – to reacquaint me freshly with the familiar world and restore a sense of proportion. My feet were sore and my face was flushed by the sun. In Berkshire, the ripe fields of corn were standing, in Oxfordshire, they were being harvested and, in Wiltshire, I saw the stubble being ploughed in. It had been a walk to arrive at the end of the summer. It had been a walk through time along the oldest road.

Goring Mill

“Join it at Streatley, the point where it crosses the Thames, at once it strikes you out and away from the habitable world in a splendid purposeful manner, running along the highest ridge of the downs.” Kenneth Grahame, 1898

A ninety-two year old man told me this year is the worst harvest he could remember. “It doesn’t want to come in the barn,” he lamented.

At East Illsley

“A broad green track runs for many a long mile across the downs, now following the ridges, now winding past at the foot of a grassy slope, then stretching away through cornfield and fallow.” Richard Jefferies, 1879

“A rough way, now wide, now narrow, among the hazel, brier and nettle. Sometimes there was an ash in the hedge and once a line of spindly elms followed it round in a curve.” Edward Thomas, 1910

On White Horse Hill

“The White Horse is, I believe, the earliest hill drawing we have in England. It is a piece of design, in another category from the other chalk figures, for it has the lineaments of a work of art. The horse, which is more of a dragon than a horse, is cut on the top of the down’s crest, so that it can only be seen completely from the air, or at a long view, from the surrounding country – but it was precisely this aspect of the Horse design that I found so significant.” Paul Nash, 1938

The Neolithic axe head found at Prebendal Farm, photo by Rob Selbourne.

At Bishopstone

At Barbary Castle

“The origin of the track goes back into the dimmest antiquity: there is evidence that it was a military road when the fierce Dane carried fire and slaughter inland, leaving his nailed bark in the creeks of the rivers, and before that when the Saxons pushed up from the sea. The eagles of old Rome were, perhaps, borne along it and yet earlier the chariots of the Britons may have used it – traces of all have been found: so that for fifteen centuries this track of primitive peoples has maintained its existence through the strange changes of the times, til now in the season the cumbrous steam ploughing engines jolt and strain and pant over the uneven turf.” Richard Jefferies, 1879

Since the man suspected of making crop circles died, his protege has adopted a different style of design.

At Avebury

At Avebury

William Morris In The East End

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

William Morris spoke at Speakers’ Corner in Victoria Park on 26th July & 11th October 1885, 8th August 1886, 27th March & 21st May 1888

If you spotted someone hauling an old wooden Spitalfields Market orange crate around the East End, that was me undertaking a pilgrimage to some of the places William Morris spoke in the hope he might return for one last oration.

The presence of William Morris in the East End is almost forgotten today. Yet he took the District Line from his home in Hammersmith regularly to speak here through the last years of his life, despite persistent ill-health. Ultimately disappointed that the production of his own designs had catered only to the rich, Morris dedicated himself increasingly to politics and in 1884 he became editor of The Commonweal, newspaper of the Socialist League, using the coach house at Kelsmcott House in Hammersmith as its headquarters.

As an activist, Morris spoke at the funeral of Alfred Linnell, who was killed by police during a free speech rally in Trafalgar Sq in 1887, on behalf of the Match Girls’ Strike in 1888 and in the Dock Strike of 1889. His final appearance in the East End was on Mile End Waste on 1st November 1890, on which occasion he spoke at a protest against the brutal treatment of Jewish people in Russia.

When William Morris died of tuberculosis in 1896, his doctor said, ‘he died a victim to his enthusiasm for spreading the principles of Socialism.’ Morris deserves to be remembered for his commitment to the people of the East End in those years of political turmoil as for the first time unions struggled to assert the right to seek justice for their workers.

8th April 1884, St Jude’s Church, Commercial St – Morris gave a speech at the opening of the annual art exhibition on behalf of Vicar Samuel Barnett who subsequently founded Toynbee Hall and the Whitechapel Gallery.

During 1885, volunteers distributed William Morris’ What Socialists Want outside the Salmon & Ball in Bethnal Green

1st September 1885, 103 Mile End Rd

20th September 1885, Dod St, Limehouse – When police launched a violent attack on speakers of the Socialist League who defended the right to free speech at this traditional spot for open air meetings, William Morris spoke on their behalf in court on 22nd September in Stepney.

10th November 1886 & 3rd July 1887, Broadway, London Fields

November 20th 1887, Bow Cemetery – Morris spoke at the burial of Alfred Linnell, a clerk who was killed by police during a free speech rally in Trafalgar Sq. ‘Our friend who lies here has had a hard life and met with a hard death, and if our society had been constituted differently his life might have been a delightful one. We are engaged in a most holy war, trying to prevent our rulers making this great town of London into nothing more than a prison.’

9th April 1889, Toynbee Hall, Commercial St – Morris gave a magic lantern show on the subject of ‘Gothic Architecture’

1st November 1890, Mile End Waste – Morris spoke in protest against the persecution of Jews in Russia

William Morris in the East End

3rd January & 27th April 1884, Tee-To-Tum Coffee House, 166 Bethnal Green Rd

8th April 1884, St Jude’s Church, Commercial St

29th October 1884, Dod St, Limehouse

9th November 1884, 13 Redman’s Row

11th January & 12th April 1885, Hoxton Academy Schools

29th March 24th May 1885, Stepney Socialist League, 110 White Horse St

26th July & 11th October 1885, Victoria Park

8th August 1885, Socialist League Stratford

16th August 1885, Exchange Coffee House, Pitfield St, Hoxton

1st September 1885, Swaby’s Coffee House, 103 Mile End Rd

22nd September 1885, Thames Police court, Stepney (Before Magistrate Sanders)

24th January 1886, Hackney Branch Rooms, 21 Audrey St, Hackney Rd

2nd February 1886, International Working Men’s Educational Club, 40 Berners St

5th June 1886, Socialist League Stratford

11th July 1886, Hoxton Branch of the Socialist League, 2 Crondel St

24th August 1886, Socialist League Mile End Branch, 108 Bridge St

13th October 1886, Congregational Schools, Swanscombe St, Barking Rd

10th November 1886, Broadway, London Fields

6th March 1887, Hoxton Branch of the Socialist League, 2 Crondel St

13th March & 12th June 1887, Hackney Branch Rooms, 21 Audrey St, Hackney Rd

27th March 1887, Borough of Hackney Club, Haggerston

27th March, 21st May, 23rd July, 21st August & 11th September, 1887 Victoria Park

24th April 1887, Morley Coffee Tavern Lecture Hall, Mare St

3rd July 1887, Broadway, London Fields

21st August 1887, Globe Coffee House, High St, Hoxton

25th September 1887, Hoxton Church

27th September 1887, Mile End Waste

18th December 1887, Bow Cemetery, Southern Grove

17th April 1888, Mile End Socialist Hall, 95 Boston St

17th April 1888, Working Men’s Radical Club, 108 Bridge St, Burdett Rd

16th June 1888, International Club, 23 Princes Sq, Cable St

17th June 1888, Victoria Park

30th June 1888, Epping Forest Picnic

22nd September 1888, International Working Men’s Education Club, 40 Berners St

9th April 1889, Toynbee Hall, Commercial St

27th June 1889, New Labour Club, 5 Victoria Park Sq, Bethnal Green

8th June 1889, International Working Men’s Education Club, 40 Berners St

1st November 1890, Mile End Waste

This feature draws upon the research of Rosemary Taylor as published in her article in The Journal of William Morris Studies. Click here to join the William Morris Society

You may also like to read about

Pollock’s Toy Theatres In Spitalfields

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

Next weekend, Pollock’s Toy Theatres return to their roots with a two day pop up at House of Annetta in Spitalfields including performances, workshops and an exhibition. Below you can read my account of the origin of the nineteenth century toy theatre movement in the East End.

William Webb, 49 Old St, 1857

William Webb, 49 Old St, 1857

These days, Old St is renowned for its digital industries but – for over a hundred years – this area was celebrated as the centre of toy theatre manufacture in London. Formerly, these narrow streets within walking distance of the City of London were home to highly skilled artisans who could turn their talents to the engraving, printing, jewellery, clock, gun and instrument-making trades which operated here – and it was in this environment that the culture of toy theatres flourished.

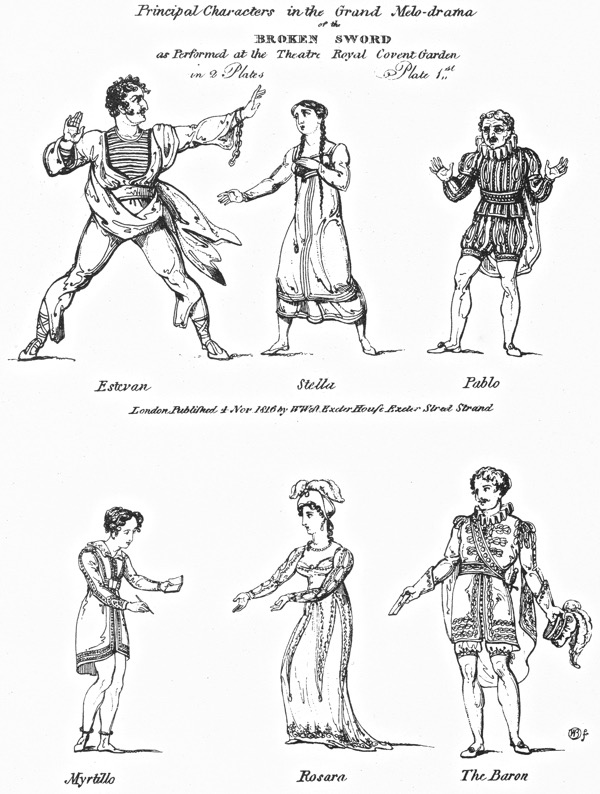

Between 1830 and 1945, at a handful of addresses within a half mile of the junction of Old St and City Rd, the modest art of publishing engraved plates of characters and scenery for Juvenile Dramas enjoyed its heyday. The names of the protagonists were William Webb and Benjamin Pollock. The overture was the opening of Archibald Park’s shop at 6 Old St Rd in 1830, and the drama was brought to the public eye by Robert Louis Stevenson in his essay A Penny Plain and Twopence Coloured in 1884, before meeting an ignominious end with the bombing of Benjamin Pollock’s shop in Hoxton St in 1945.

Responsibility for the origin of this vein of publishing belongs both to John Kilby Green of Lambeth and William West of Wych St in the Strand, with the earliest surviving sheets dated at 1811. Green was just an apprentice when he had the notion to produce sheets of theatrical characters but it was West who took the idea further, publishing plates of popular contemporary dramas. From the beginning, the engraved plates became currency in their own right and many of Green’s vast output were later acquired by Redington of Hoxton and eventually published there as Pollock’s. West is chiefly remembered for commissioning artists of acknowledged eminence to design plates, including the Cruickshank brothers, Henry Flaxman, Robert Dighton and – most notably – William Blake.

Green had briefly collaborated to open Green & Slee’s Theatrical Print Warehouse at 5 Artillery Lane, Spitalfields, in 1805 to produce ‘The Tiger’s Horde’ but the first major publishers of toy theatres in the East End were Archibald Park and his family, rising to prosperity with premises in Old St and then 47 Leonard St between 1830 until 1870.

Park’s apprentice from 1835-42, William Webb, set up on his own with shops in Cloth Fair and Bermondsey before eventually opening a quarter a mile from his master at 49 (renumbered as 146) Old St in 1857. Webb traded here until his death in 1898 when his son moved to 124 Old St where he was in business until 1931. Contrary to popular belief, it was William Webb who inspired Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous essay upon the subject of toy theatres. Yet a disagreement between the two men led to Stevenson approaching Webb’s rival Benjamin Pollock in Hoxton St, who became the subject of the story instead and whose name became the byword for toy theatres.

In 1876, at twenty-one years old, Benjamin Pollock had the good fortune to acquire by marriage the shop opened by his late father-in-law, John Redington in Hoxton in 1851. Redington had all the theatrical plates engraved JK Green and, in time, Benjamin Pollock altered these plates, erasing the name of ‘Redington’ and replacing it with his own just as Redington had once erased the name ‘Green’ before him. Although it was an unpromising business at the end of the nineteenth century, Pollock harnessed himself to the work, demonstrating flair and aptitude by producing high quality reproductions from the old plates, removing ‘modern’ lettering applied by Redington and commissioning new designs from the naive artist James Tofts.

In 1931, the writer AE Wilson had the forethought to visit Webb’s shop in Old St and Pollock’s in Hoxton St, talking to William Webb’s son Harry and to Benjamin Pollock, the last representatives of the two surviving dynasties in the arcane world of Juvenile Dramas. “In his heyday, his business was very flourishing,” admitted Harry Webb speaking of his father,” Why, I remember we employed four families to do the colouring. There must have been at least fifteen people engaged in the work. I could tell their work apart, no two of them coloured alike. Some of the work was beautifully done.”

Harry recalled visits by Robert Louis Stevenson and Charles Dickens to his father’s premises. “Up to the time of the quarrel, Stevenson was a frequent visitor to the shop, he was very fond of my father’s plays. Indeed it was my father who supplied the shop in Edinburgh from which he bought his prints as a boy,” he told Wilson.

Benjamin Pollock was seventy-five years old when Wilson met him and ‘spoke in strains not unmingled with melancholy.’ “Toy theatres are too slow for the modern boy and girl,” he confessed to Wilson, “even my own grandchildren aren’t interested. One Christmas, I didn’t sell a single stage.” Yet Pollock spoke passionately recalling visits by Ellen Terry and Charlie Chaplin to purchase theatres. “I still get a few elderly customers,” Pollock revealed, “Only the other day, a City gentleman drove up here in a car and bought a selection of plays. He said he had collected them as a boy. Practically all the stock has been here fifty years or so. There’s enough to last out my time, I reckon.”

Shortly after AE Wilson’s visit to Old St & Hoxton, Webb’s shop was demolished while Benjamin Pollock struggled to earn even the rent for his tiny premises until his death in 1937. Harry Webb lived on in Caslon St – named after the famous letter founder who set up there two centuries earlier – opposite the site of his father’s Old St shop until his death in 1962.

Robert Louis Stevenson visited 73 Hoxton St in 1884. “If you love art, folly or the bright eyes of children speed to Pollock’s” he wrote fondly afterwards. Stevenson was an only child who played with toy theatres to amuse himself in the frequent absences from school due to sickness when he was growing up in Edinburgh. I too was an only child enchanted by the magic of toy theatres, especially at Christmas, but I cannot quite put my finger on what still draws me to the romance of them.

Even Stevenson admitted “The purchase and the first half hour at home, that was the summit.” As a child, I think the making of them was the greater part of the pleasure, cutting out the figures and glueing it all together. “I cannot deny the joy that attended the illumination, nor can I quite forget that child, who forgoing pleasure, stoops to tuppence coloured,” Stevenson concluded wryly. I cannot imagine what he would have made of Old St’s ‘Silicon Roundabout’ today.

Drawings for toy theatre characters by William Blake for William West

The sheet as published by William West, November 4th 1816 – note Blake’s initials, bottom right

Another sheet engraved after drawings by William Blake, 1814

Another sheet engraved after drawings by William Blake, 1814

124 Old St, 1931

73 Hoxton St (formerly 208 Hoxton Old Town) 1931

Benjamin Pollock at his shop on Hoxton St in 1931

Fourteenth Annual Report

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

Fourteen years ago this week I began publishing daily in these pages with the ambition of reaching at least ten thousand posts, which would take twenty-seven years and four months. It seemed an outlandish endeavour then, yet recently I passed the halfway point without even noticing until a reader wrote to congratulate me.

I was motivated by the knowledge that my parents had both died at exactly the same age and ten thousand days would deliver me to that time. So I sought a means to make my days as rewarding and productive as I could through writing and participating in the life surrounding me. I happy to admit to you that in these terms the project has succeeded beyond all expectation.

Ten years ago, the readers of Spitalfields Life campaigned to save the Marquis of Lansdowne from 1838 in Haggerston from demolition and today it is restored as part of the Museum of the Home. Five years ago, we campaigned to save the five-hundred-year-old Bethnal Green Mulberry and now it is protected. This year, the mulberry cuttings have rooted and we plan to distribute them this autumn to those patient souls who contributed £100 or more to the legal fund.

As I write, Liverpool St Station and the Bishopsgate Bathhouse are under threat from development, while the #SaveBrickLane Coalition – of which Spitalfields Life is part – prepares to go to the Supreme Court to challenge the Truman Brewery’s plans for a shopping mall.

Down in Whitechapel, the bell foundry has been rotting since its closure five years ago, acquiring layers of graffiti now that the neglect is tangible. The developers have abandoned their plan for a boutique hotel and it has been on sale without takers for a year, despite a standing offer at market value from the London Bell Foundry to buy it to start casting bells again and cherish the historic buildings.

On a brighter note, in November last year it was my great delight to speak at the party for the tenth birthday of the East End Trades Guild of which I am proud have been one of the founders. You may have read recently of the Guild’s heroic campaign to champion the rights of Len Maloney and other tenants of railway arches in the face of excessive rent increases.

Eleven years have passed since I wrote my book Spitalfields Life and ten since I became a publisher myself with The Gentle Author’s London Album in 2013. Then I published twenty titles before the pandemic called a halt to operations. But this autumn I plan relaunch Spitalfields Life Books starting with a crowdfunding campaign next month and at least four new titles in hand.

When I take a reckoning of these milestones and contemplate the future, I do not regret my choice to embrace the relentless progress of life in this corner of London.

Thus, with all these thoughts in mind, I come to the end of the fourteenth year in the pages of Spitalfields Life.

I am your loyal servant

The Gentle Author

25th August 2023

The Gentle Author’s cat, Schrodinger (formerly of Shoreditch Church)

You may like to read my earlier Annual Reports

Summer At Bow Cemetery

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

At least once each Summer, I direct my steps eastwards from Spitalfields along the Mile End Rd towards Bow Cemetery, one of the “Magnificent Seven” created by act of Parliament in 1832 as the growing population of London overcrowded the small parish churchyards. Extending to twenty-seven acres and planned on an industrial scale, “The City of London and Tower Hamlets Cemetery” as it was formally called, opened in 1841 and within the first half century alone around a quarter of a million were buried here.

Although it is the tombstones and monuments that present a striking display today, most of the occupants of this cemetery were residents of the East End whose families could not afford a funeral or a plot. They were buried in mass public graves containing as many as forty bodies of random souls interred together for eternity. By the end of the nineteenth century the site was already overgrown, though burials continued until it was closed in 1966.

Where death once held dominion, nature has reclaimed the territory and a magnificent broadleaf forest has grown, bringing luxuriant growth that is alive with wildlife. Now the tombstones and monuments stand among leaf mould in deep woods, garlanded with ivy and surrounded by wildflowers. Tombstones and undergrowth make one of the most lyrical contrasts I can think of – there is a beautiful aesthetic manifest in the grim austerity of the stones ameliorated by vigorous plant life. But more than this, to see the symbols of death physically overwhelmed by extravagant new growth touches the human spirit. It is both humbling and uplifting at the same time. It is the triumph of life. Nature has returned and brought more than sixteen species of butterflies with her.

This is the emotive spectacle that leads me here, turning right at Mile End tube station and hurrying down Southern Grove, increasing my pace with rising expectation, until I walk through the cemetery gates and I am transported into the green world that awaits. At once, I turn right into Sanctuary Wood, stepping off the track to walk into a tall stand of ivy-clad sycamores, upon a carpet of leaves that is shaded by the forest canopy more than twenty metres overhead and illuminated by narrow shafts of sunlight descending. It is sublime. Come here to see the bluebells in Spring or the foxgloves in Summer. Come at any time of the year to find yourself in another landscape. Just like the forest in Richard Jefferies’ novel “After London,” the trees have regrown to remind us what this land was once like, long ago before our predecessors ever came here.

Over time, the tombstones have weathered and worn, and some have turned green, entirely harmonious with their overgrown environment, as if they sprouted and grew like toadstools. The natural stillness of the forest possesses greater resonance between cemetery walls and the deep green shadows of the woodland seem deeper too. There was almost no-one alive to be seen on the morning of my visit, apart from two police officers on horseback passing through, keeping the peace that is as deep as the grave.

Just as time mediates grief and grants us perspective, nature also encompasses the dead, enfolding them all, as it has done here in a green forest. These are the people who made East London, who laid the roads, built the houses and created the foundations of the city we inhabit. The countless thousands who were here before us, walking the streets we know, attending the same schools, even living in some of the same houses we live in today. The majority of those people are here now in Bow Cemetery. As you walk around, names catch your eye, Cornelius aged just two years, or Eliza or Louise or Emma, or Caleb who enjoyed a happy life, all over a hundred years ago. None ever dreamed a forest would grow over their head, where people would come to walk one day to discover their stones in a woodland glade. It is a vision of paradise above, fulfilled within the confines of the cemetery itself.

As I made my progress through the forest of tombstones, I heard a mysterious noise, a click-clack echoing through the trees. Then I came upon a clearing at the very heart of the cemetery and discovered the origin of the sound. It was a solitary juggler practicing his art among the graves, in a patch of sunlight. There is no purpose to juggling than that of delight, the attunement of human reflexes to create a joyful effect. It was a startling image to discover, and seeing it here in the deep woods – where so many fellow Londoners are buried – made my heart leap. In the vast wooded cemetery there was just me, the numberless dead and the juggler.

You may also like to read about