David Eyre, Chef

This is David Eyre, Head Chef at Eyre Brothers in Shoreditch, where, last night in his kitchen, he and his team prepared sixty meals between eight and nine o’clock, or if you include starters and side dishes, one hundred and twenty dishes – one every thirty seconds. Yet more important than David’s obvious panache and dexterity, is the superlative quality of the food at his Spanish/Portuguese restaurant which specialises in tapas and deft versions of traditional Iberian dishes.

It is no surprise that there is a discernible shine upon David’s brow and his stray locks have strayed – although in the circumstances I think we may indulge these details that only enhance the charm of his raffishly handsome Humphrey Bogart features, augmented by the deep baritone voice in which he calls out orders to his fellow chefs. Caught here in this fleeting moment of stillness within the clamour of the evening’s service, David was briefly silent, clutching himself in disbelief and wonder and joy at the horde of happy diners, noisily enjoying their meals in the moodily lit restaurant next door.

“I love cooking, so it suits me brilliantly that people want to eat what I like to cook,” David admitted to me with a broad grin, as if this state of affairs were merely accidental, when the truth is that he one of those who has encouraged the taste for Portuguese and Spanish cuisine in this country over the last twenty years.

It was David’s childhood in Mozambique, a former Portuguese colony, that gave him his passion for this particular food. “My father came from Spitalfields originally, ” he confided to me,“and my mother from the West Indies and I was sent to a school in Zimbabwe where the food was really horrendous, though I was fortunate that my mother was a fine cook. I came to London to do an Engineering degree but my passport was British, and I didn’t want to return to Mozambique and become an ex-patriot, so I decided to stay here. And I got offered a job at Massey Ferguson, the tractor manufacturer, but when I saw where I was going to work, I said, ‘I’m going to get a job as a waiter and you can keep this!'”

With a business partner that he met while working in Covent Garden, David opened The Eagle in the Farringdon Rd, Clerkenwell – the celebrated gastropub that set the template adopted by thousands of others in subsequent years. Yet even this spectacularly influential endeavour is one that David seeks to explain away. “We couldn’t get the finance to open a restaurant, so we opened a pub,” he revealed, “I was very briefly married at the time and my wife’s aunt was rich. She said, ‘The recession’s coming but people always want a drink, so open a pub.’ And we managed to scrape together fifteen thousand pounds and got a pub because the government monopoly commission was forcing breweries to sell them off at the time. It was the constraints that made it possible. We served coffee and steak sandwiches and braised vegetables (and Italian sausages because Gazzano’s was next door). It was all about the ingredients. And the menu changed twice a day because we had no fridge.”

Let me admit, in those days I had an office in Clerkenwell where I went to write every day and, if my work was going well, I treated myself to a delicious steak sandwich at The Eagle as a reward. Although it seems difficult to remember now, there were no other pubs at that time where you good get such high quality Mediterranean food in a bar.

Displaying his characteristic trait, rather than attribute The Eagle’s extraordinary success to his talent as a chef – and skirting over how he taught himself to cook – instead David confessed with a pitiful smile of self parody, “I used to groan the busier it got, because it caused me more and more sweat!” Seven years later, David moved on to open Eyre Brothers in Charlotte Rd, Shoreditch – “a jumped-up sandwich bar,” as he termed it, and from there it was only a short hop to the current restaurant.

“The reason I take my inspiration from Portuguese culture,” concluded David, “is because it is a modest way of life, in which peasants eat better than kings. I abhor pretentious restaurant food, designed on plates with tiny portions, that’s all about the chef and not about the ingredients. The English like food where they can see what they’re getting and here, even though this is a modernist restaurant, it is really granny’s cooking – that is if you have a granny who can cook!”

For one service, I joined David in the kitchen where he stood at the centre, studying the orders as they came in, giving instructions to his sous chefs for vegetables and tapas, while they called back their timings before he composed each dish upon the plate personally, leaning over with hunched shoulders to place the food with conscientious delicacy. David was in constant motion, turning and striding up and down, occasionally raising his arms in flights of lyricism – in gestures that were in part those of a conductor, in part those of the triumphant victor and in part those of hysteria. Yet as the orders accelerated, the team got onto a roll and the kitchen became a very dynamic place to be as everyone worked together as virtuosi under David’s tutelage. I realised I preferred to be there with them in the kitchen rather than sitting in the restaurant, I did not envy the customers – except, that is, for their food cooked by David Eyre.

You may also like to read about

Maria Pellicci, the Meatball Queen of Bethnal Green

The Pump of Death

See these people come and go at the junction of Fenchurch St and Leadenhall St in the City of London in 1927. Observe the boy idling in the flat cap. They all seem unaware they are in the presence of the notorious “Pump of Death” – that switched to mains supply fifty years earlier in 1876, when the water began to taste strange and was found to contain liquid human remains which had seeped into the underground stream from cemeteries.

Several hundred people died in the resultant Aldgate Pump Epidemic as a result of drinking polluted water – though this was obviously a distant memory by the nineteen twenties when Whittard’s tea merchants used to “always get the kettles filled at the Aldgate Pump so that only the purest water was used for tea tasting.”

Yet before it transferred to a supply from the New River Company of Islington, the spring water of the Aldgate Pump was appreciated by many for its abundant health-giving mineral salts, until – in an unexpectedly horrific development – it was discovered that the calcium in the water had leached from human bones.

This bizarre phenomenon quickly entered popular lore, so that a bouncing cheque was referred to as “a draught upon Aldgate Pump,” and in rhyming slang “Aldgate Pump” meant to be annoyed – “to get the hump.” The terrible revelation confirmed widespread morbid prejudice about the East End, of which Aldgate Pump was a landmark defining the beginning of the territory. The “Pump of Death” became emblematic of the perceived degradation of life in East London and it was once declared with superlative partiality that “East of Aldgate Pump, people cared for nothing but drink, vice and crime.”

Today this sturdy late-eighteenth century stone pump stands sentinel as the battered reminder of a former world, no longer functional, and lost amongst the traffic and recent developments of the modern City. No-one notices it anymore and its fearsome history is almost forgotten, despite the impressive provenance of this dignified ancient landmark, where all mileages East of London are calculated. Even in the old photographs you can trace how the venerable pump became marginalised, cut down and ultimately ignored.

Aldgate Well was first mentioned in the thirteenth century – in the reign of King John – and referred to by sixteenth century historian, John Stowe, who described the execution of the Bailiff of Romford on the gibbet “near the well within Aldgate.” In “The Uncommercial Traveller,” Charles Dickens wrote, “My day’s business beckoned me to the East End of London, I had turned my face to that part of the compass… and had got past Aldgate Pump.” And before the “Pump of Death” incident, Music Hall composer Edgar Bateman nicknamed “The Shakespeare of Aldgate Pump,” wrote a comic song in celebration of Aldgate Pump – including the lyric line “I never shall forget the gal I met near Aldgate Pump…”

The pump was first installed upon the well head in the sixteenth century, and subsequently replaced in the eighteenth century by the gracefully tapered and rusticated Portland stone obelisk that stands today with a nineteenth century gabled capping. The most remarkable detail to survive to our day is the elegant brass spout in the form of a wolf’s head – still snarling ferociously in a vain attempt to maintain its “Pump of Death” reputation – put there to signify the last of these creatures to be shot outside the City of London.

In the photo from 1927, you can see two metal drinking cups that have gone now, leaving just the stubs where the chains attaching them were fixed. Tantalisingly, the brass button that controls the water outlet is still there, yet, although it is irresistible to press it, the water ceased flowing in the last century. A drain remains beneath the spout where the stone is weathered from the action of water over centuries and there is an elegant wrought iron pump handle – enough details to convince me that the water might return one day.

Looking towards Aldgate.

The water head, reputed to be an image of the last wolf shot in London.

The pump was closed in 1876 and the outlet switched to mains water supply.

Archive photographs copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

Great News!

Although Thomas Rowlandson had the unexpected good luck to inherit a fortune of £7,000 from a French aunt, he was born as the son of a wool and silk merchant in Old Jewry in the City of London, who went bankrupt when Thomas was just two years old. Yet due to a profligate nature, Thomas’ inheritance got quickly squandered and he turned to caricature as a means of income, achieving memorable success. A series of life experiences which may permit us to surmise that Rowlandson’s use of the term “Lower Orders,” in the title of his “Characteristic Sketches of the Lower Orders” (a set of fifty prints published in 1820), was not entirely without irony.

While many sets of images of the “Cries of London” over the centuries presented a harmonious social picture in which hawkers knew their place, I treasure Rowlandson’s work for the exuberant anarchy that he brings to his subjects who stride energetically through the London streets like they own them, gleefully lacking any sign of subservience. Rude, rambunctious, horny and venal as rats, these are Londoners that we can all recognise and, even though Rowlandson’s vision is not a flattering view of humanity, his lack of sentimentality endears us to his subjects, in spite of their flawed natures.

In Rowlandson’s work, the drama of the city is all-consuming as everyone strives for gratification, whether making a living, seeking sexual pleasure, or purely to assert their being. And, to the outside eye, these inhabitants appear almost childlike in their preoccupations, because nobody has time for self-conscious reflection when everyone is too busy pursuing life.

In the Newspaper Seller and the Cab Driver, the “lower orders” are placed in relation to their “superiors” and, in each case, the tension of the relationship is obvious. The Paper Sellers’ trumpet and loud cries are irking their customers by awakening them in the early morning, while the Cabbie is affronted by his meagre tip and challenges his passengers. And neither shows any regard for those who are offended by their lack of manners.

By contrast, in the plates of the Postman and the Rose Seller, the tension is erotic – the Postman checks out his young female customer while a voyeur cranes from a balcony above and the Rose Seller assumes a faux innocence when an old lecher chucks her under the chin – in each instance proposing transactions both covert and overt. Then there are the clownish Cat & Dogs’ Meat Seller, beset by hungry dogs, and the senile Night Watchman, oblivious of burglars. Only two hawkers demonstrate humility, the Knife Grinder preoccupied with his work and the Curds & Whey Seller sitting to watch the happy young mother and her children with tacit envy. Finally, the China Sellers and the Tinker mending pots and kettles are grotesques. The China Sellers ingratiate themselves in a predatory manner, but the Tinker meets his match in the demanding old hag.

There are some appealingly scruffy spontaneous lines here that would not be out of place in a drawing by Quentin Blake. By his early sixties, Rowlandson had sacrificed the precise elegant flowing lines of his early career for these off-the-cuff sketches which communicate character with great immediacy.

Ultimately, the central ambiguity and source of drama in Rowlandsons “Characteristic Sketches of the Lower Orders” is the question – Who is playing who? And even in this selection, of just ten from the set of fifty, it is apparent that there is no simple answer. Instead, Rowlandson presents a series of precise scenarios that trace delicate lines of social and economic distinction with wit and humanity, avoiding any didactic or moral conclusion. Above all, these wonderful prints illustrate that moral worth does not equate with the “Lower” or “Higher” orders, and their relative economic worth. Thomas Rowlandson’s Londoners are just as good and as bad each other.

Wot d’yer call that?

Cats and Dogs’ Meat?

Letters for Post?

Past one o’clock and a fine morning!

Buy my Sweet Roses?

Knives and Scissors to Grind?

Curds and Whey?

Any Earthenware? Buy a Jug or a Teapot?

Constable’s Dues at the Tower of London

“Back in the mists of time….” began Lord General Richard Danatt – ex-Chief of Staff of the Army, now one hundred and fifty-ninth Constable of the Tower of London – as we sat in the magnificent Queen’s House at the Tower overlooking the Thames, which seemed to be there sparkling solely for our pleasure that morning. “Back in the mists of time, every ship that came upstream had to unload a portion of its cargo in return for the protection of the Tower,” he continued, glancing at the river,“and the Constable of the Tower collected the dues as the Sovereign’s proxy.”

And he gave a private smile because, as a seasoned military man, he is alive to the ambiguity of this tradition which began in the fourteenth century – admitting later that one of his predecessors John de Cromwell was put on trial for piracy in the fourteenth century. Nowadays, the Constable’s Dues is purely ceremonial and the only involvement with piracy recently was when the American ship that rescued the British hostages from the Somali pirates in the Gulf was invited to participate as a gesture of thanks. Yet I learnt that morning that HMS Westminster would be departing for Libya immediately after the ceremony, due to the escalating crisis there, and it emphasised how integral the life of the Tower is to the armed forces, manned by Yeoman Warders who are all ex-servicemen.

When I arrived at the Tower to meet Lord Dannatt, an hour before the ceremony, the fresh parallel stripes upon the lawn at Tower Green were the first hint that something was afoot. Days before, the scaffolding had been removed from the mythic eleventh century White Tower, revealed gleaming in the Spring sunshine after a three year programme of cleaning and renovation. Lord Dannatt sat on the couch beneath his most celebrated antecedent as Constable of the Tower, the Duke of Wellington, and explained that his is the most senior position at the Tower, in one of the oldest offices in the land, dating back to within a few years of the Norman Conquest. He told me the Iron Duke was Prime Minister twice whilst Constable of the Tower – a feat he did not intend to rival. Instead wanted to tell me about the fine choir he has encouraged in St Georges Chapel within the White Tower, where members of the public may come to a service any Sunday morning without the requirement of buying a ticket.

Then when he went off to change into his regalia, and I walked down to the waterfront where a drum band was stationed at the entrance to the Tower and sailors from HMS Westminster under the command of Tim Green were arrayed in ranks outside, two in front carrying an oar upon which was slung the crucial keg of wine – the Constable’s Dues. Yeoman Warders in their ceremonial red uniforms trimmed with gold braid were in evidence, scurrying through the tourist crowds with silver maces and staffs with ferocious blades mounted upon them. There was a certain frisson among the visitors who were puzzled by these strangely dressed men, like the ghosts of another age. Yet the reality was the converse, the Yeoman Warders were enacting a ritual which is six hundred years old while the tourists were interlopers of the modern day.

At midday, the Yeoman Warders swung the gates shut and Commander Tim Green approached, requesting entry. Then “words were spoken” in theatrically-raised voices – that I did not hear exactly – but which amounted to a negotiation in which the keg of wine was offered to the Constable in return for the ship’s passage up the Thames. John Keohane, the Chief Yeoman Warder, operating on behalf of the Constable duly accepted the offer and the gates were opened to admit the crew. Then John, with a dignified spirit that few could rival, led the procession with his mace in the shape of the Tower upon his shoulder. And as I followed, running alongside the drum band and the sailors marching in rank, through the narrow roadways and overhanging stone arches of the Tower, with the sound reverberating all around, I had the feeling of experiencing history – of an event played out for centuries in this ancient mysterious space that was designed for it, and has been here longer than anything else in London. In those moments, I was the ghost witnessing hundreds of years passing before my eyes in endless processions marching through. It was the seduction of pageantry.

Up on Tower Green, the Constable was waiting, resplendent in his long braided coat with an extravagantly feathered bicorn hat in the manner of the Iron Duke. The drum band and the sailors lined up in perfect formation upon the immaculate lawn and began to turn pale in the face of the biting wind at Winter’s end, as they stood immobile for the duration. As the keg of wine was presented, thanks were exchanged before everybody disappeared inside the Queen’s House for a reviving glass of spirits. Before he joined them, I had the opportunity of a brief chat with John Keohane who revealed he would be retiring in September – and leaving the Tower – making this the last Constable’s Dues at which he would officiate. It was poignant moment, watching John being photographed in front of the newly revealed White Tower. “It’s a job I love,” he confided to me with a soulful grin, casting his eyes around Tower Green where the ravens had moved into the space vacated by the procession. “Seven years as chief Yeoman Warder,” he mused quietly after the drama of the morning, “- a job I never expected to get when I came here twenty-three years ago.”

“Can I ask you something?” I enquired impertinently, as we shook hands,“Is there anything inside the keg?” And he looked at me in surprise. “Wine!” he said, breaking into radiant smile, looking at me in a quizzical fashion as if I had entirely missed the point,“We’ll decant it into bottles and enjoy it after the parade on Easter Sunday.” Then, in that moment, I understood everything which happened that morning anew. Although a ceremony, it was no mere performance but a ritual with vivid and authentic meaning for the participants, because the Tower of London is not where history was enacted – it is where history happened, and these people recognise they are part of that continuum stretching back over a thousand years upon this spot. “Back in the mists of time…” as the Constable put it.

Watch the ceremony of the installation of the Constable of the Tower of London in 1938 by clicking here

Lord General Richard Dannatt, Constable of the Tower of London, with the Duke of Wellington – his most celebrated predecessor.

John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder of the Tower of London

The keg of wine as the Constable’s Dues.

Commander Tim Green of HMS Westminster

The gate of the Tower is closed against the ship’s crew until “words are spoken”

The Chief Yeoman Warder leads the procession followed by the drum band ahead of the ship’s crew with the Constable’s Dues.

On Tower Green

The keg of wine is presented by the crew of HMS Westminster

Lord General Richard Dannatt in his uniform as Constable of the Tower.

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You can read my pen portrait of John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

Brick Lane Market 2

Pickles

Had I walked this street on a Sunday in 1911, I would have had florins or farthings or halfpennies in my pocket, and I would have been in search of a linnet or a parrot or maybe a Japanese Nightingale to share my home. And this narrow road would have been packed with all variations of humanity, a dark heaving mass ebbing and flowing, searching high amongst the piles of cages for a feathered companion to add song to their days. And, according to George Sims in his book “Off the Track in London,” when you buy a canary off a road hawker “he puts it in a little paper bag for you, and you carry it away as if it were a penny bun.”

But it is not 1911, it is now, and I am in search of a woman called “Pickles” who has traded at the market on and off for the last thirty years.

Ahead of me, I see a petite woman, pretty, with a red flower in her hair. The colour cuts through the grey light like a burst of joy. She stands in front of her Aladdin’s cave, part-tucked into a wall next to an old railway chapel. It is filled with the clothes and trinkets of past lives; rows of beads and racks of shoes, of hats – once someone’s favourite skirt, favourite jumper – ready to live again on swaying bodies. A treasured hoard of glass and crockery, of books and purses, and a mother’s hand-made dolls, and all – all – so cared for by Pickles, and displayed as she once would have done in her shop, the one with the old-fashioned bell above the door.

“Every class of man and woman came to that old bird market,” says Pickles, “and the same today. Markets – they’ve always been a great leveller,” and she hands me a welcomed cup of tea.

“I was hit hard by the development of Spitalfields. I always thought that this was a place that if you fell upon hard luck, hard times, you could start again. But it’s been difficult. When the old bridge was taken down, I lost everything – home and livelihood. Change bulldozes everything. I wrote to Prince Charles, and even Prince Charles tried to save the bridge. Development has no place for the everyman history,” she adds, her green eyes flashing. And I feel the injustice, a force potent and understandable. A sense of wrongness, an awakening to a world that is suddenly awry and unrecognizable.

“Even for kids, there are no discoveries to make anymore, nowhere to play,” Pickles adds. “Imagination is squashed – such a lack of creativity. I played on bomb sites when I was a child, and in the sink mud of the Thames,” she laughs. “I had a lot of freedom. Well it was after the war, and I suppose my mum had got quite desensitized, because of all the things she’d seen. She wasn’t overly protective. When I was nine, I got run over on the Wandsworth Bridge Road. When the policeman came to tell my mum, she said, ‘She’s dead, isn’t she?’ I suppose people were used to expecting the worst. When she came to see me in the hospital, I made out I was worse than I was and groaned and pretended to pass out. I had to stay like that till she’d gone – serves me right!” she laughs.

“Later I went with my mum and lived in a gypsy caravan. That’s where I learnt how to recycle things – make use of everything. Mum used to cut the zips and buttons off clothes and I‘d take them to the rag man and collect money. I’ve worked since I was fourteen. Played truant and worked as a waitress, a shop assistant in Woolworths, worked in a hat factory, started as a packer and ended up being able to make a block and hats. I’ve always done something, kept going. Always been a bit of an outsider too – I’ve lived up North, lived down here, lived wherever I could make a home.”

“Maybe it’s the gypsy caravan in your blood,” I venture.

“Maybe. But even my Nan moved a lot during the war. I think she was trying to outrun Hitler!”

“So what did you do after the development? After you were moved on?” I ask, and she points to the yellow van with the image of Mickey Mouse and “Pickles Parties” painted along the side. “I couldn’t do markets for a bit. A lot of stuff was ruined or in storage, and it hurt too much. So I did that. I made lucky dips and did face painting.”

And I marvel at Pickles’ spirit, at her passion and articulacy. Her tenacity and style is infectious. And as a sudden chill whips along the street, I’m about to cap my pen, when I stop.

“I have to ask you, you know,” I say.

“Oh Blimey, not my age!”

“No. Why are you called Pickles?”

“Ah,” she laughs, “that’s another story…”

Portrait copyright © Jeremy Freedman

ENVOI

My week is over and thanks are due. Thank you to the Gentle Author for the opportunity to spend time in Spitalfields Life – it is a beautiful and memorable world. Thank you to photographer Patricia Niven who has been with me all week and who has enhanced all I have written with the most wonderful and affecting images.

Sarah x

Photograph copyright © Patricia Niven

Grace Payne, City of London Resident

I am looking out from the thirty-sixth floor of one of the Barbican Towers. The clouds are low, and the City is trapped beneath a dismal fug. The spire of Christ Church, Spitalfields, is barely visible in the distance.

“You used to be able to see the Monument from here, but now it’s dwarfed by all the towers. Nothing is as it was, except perhaps the Honourable Artillery Company ground,” says Grace, as she places the tea tray down and offers me a delicious homemade flap jack. “Not that everything in the past is necessarily good. If you go back far enough, it becomes a hell of a lot worse.

My Granny had four children and her husband died of consumption. Died like flies from overcrowding then. Mummy was only six. Granny ended up living in the Corporation Buildings in Farringdon Road – The old Guardian home – There was one parlour, one bedroom and a scullery with a copper pot, and a loo out the back. I can still smell the linoleum in that parlour.”

I have known the ubiquitous Grace Payne for five years now. We sing in a Community Choir together and the first things I noticed about her was her style, her elegance, and her irrepressible vitality. Over this time I’ve got to know a little about her working life, her sixteen years spent in Hong Kong, a little about her family. But this afternoon, over a pot of tea, she is taking me back to a time before.

“I was born in 1924. We lived in a condemned tenement building in Brixton,” she tells me. “My father was in the police there. We then moved to Streatham and I went to Sunnyhill Primary School – think it’s still there actually. In 1934, my father was made Chief Inspector of a division at the Minories and we lived at the police station at number sixty. If you look for it now, it’s just a highway. I took a junior county scholarship for the City of London School for Girls, which was in Carmelite Street then. The headmistress was a Miss Turner: a slim woman, hair in a bun, flat buttoned shoes, dressed in purple, you know the type. Wouldn’t allow a book to be placed on top of the bible in her presence! It was quite a snobby environment, and I had rather a South London accent. My mother, a working class woman, went to meet Miss Turner and was asked, ‘What would happen about the fees if your husband lost his job?’ So insensitive. They recommended me to have elocution lessons.

I used to travel from Mark Lane Station (now Tower Hill) to Blackfriars. There were no school friends or neighbours who lived near me, except my friend Olga Raphalowsky who lived in Spitalfields. They were White Russian Refugees. Her father was a GP and they lived over the surgery. This family was like another world to me. Thick accents, intellectuals, wonderful and friendly – so exotic, not at all English. Uncle Danny was a film maker! I was still friends with Olga up until she died two years ago.

Oh I’ve stayed in touch with many of my school friends – Margaret and Mary, and Hazel Morris. I suppose wartime brought us together. In November 1940 we were evacuated to Keighley in Yorkshire. We waited in the church hall for one’s name to be called out and for someone to take you home. Margaret and I were billeted together with a family called Lumb. We were there for two years with the mother and father and three year old Jean. Well, Jean comes to stay with us now when she comes to London. She must be nearly seventy-three.

Keighley was grim. War was pretty bad by then and rationing tight. Coal was in short supply and homes were cold. But Margaret and I used to go into Bradford for the Hallé concerts. Henry Wood was conducting one night and he apologised for wearing a lounge suit. He explained that his suitcase had been lost on the train and that’s why he didn’t have his proper dress.

Before evacuation, however, we’d gone to live in Snow Hill police station because my father had again been promoted. He was in charge of all the ARP warden’s too. There was sticky tape across the bow windows and sandbags piled out the front. The police station had a flat roof and I used to collect shrapnel that had fallen during the night. I had a great collection. One morning, I found cans of fruit on the roof that had blown over from an exploding warehouse. I used to sleep in the basement and my parents slept at the back. A bomb fell on our building in September 1940. It was 10:30, 11:15 at night, I think. Four bombs were dropped all in a line – one hit the Evening Standard building, another St Bart’s hospital, another I can’t remember, but the last fell on us. I remember my parents coming out covered in dust.

From my school days until now, the one thing I’ve always done is sing in a choir – maybe with a few gaps. But my father always sang in a choir. He started the City of London Police Choral Society, started it during the war. He sang at Douglas’s and my wedding. We were married in St Bartholomew the Great Church. It was wonderful, didn’t cost an arm and a leg in those days – The film “Four Weddings and a Funeral” changed all that. Cost us seven shillings and sixpence, I think.

We didn’t consciously move back to the Barbican after our travels. We were living in South Kensington. But when we got to the age of seventy, we were nagged by one of our daughters to move before one of us had a stroke or something! But I can’t imagine not living here. At our age there’s so much to do. If we lived in the country what the hell would we do?”

There is a moment to pause, and I write: City of London Old Girl, Imperial College Old Girl, wife, mother, university teacher, text book writer, traveller, jewellery maker, and all round good egg.

“Anything else, Grace?” I ask.

“Grandmother and great grandmother,” she says. “Family, it’s the thing that matters most of all. Everything else is rather trivial in comparison,” she says and she smiles. And I know she is right.

I look up from my notebook and realize hours have passed. Night has fallen. We sit quietly as lights erupt across the spent City.

“I was also a model, you know,” says Grace matter-of-factly.” Must have been seven because after that I cut my hair and they didn’t want me then. I modelled for a Couture House in Bond Street – ‘Russell and Allen’s’ – I came up on the tram from Streatham, lovely to have a day off school. Also modelled for Paton and Baldwins’ knitting patterns.”

I take another succulent flap jack. I am happy. Grace Payne I salute you.

Home made flapjacks following a sixty year old recipe.

Grace’s first teddy bear.

Grace in her kitchen jewellery workshop.

Grace in her modelling days.

Grace at the Police Sports Day around 1930.

At Sunny Hill Road Primary School.

Grace’s father

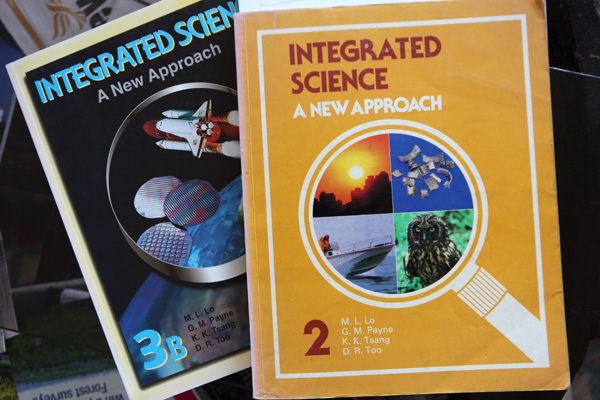

Science text books from Hong Kong co-written by Grace.

Grace Payne

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

Trevor Chelsea, Smithfield Butcher

Trevor Chelsea

“It was market-morning. The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire, and a thick steam, perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle, and mingling with the fog, which seemed to rest upon the chimney-tops, hung heavily above … Countrymen, butchers, drovers, hawkers, boys, thieves, idlers, and vagabonds of every low grade, were mingled together in a mass…” – This is Charles Dickens’ vivid account of the livestock market in Smithfield, described in Oliver Twist in 1838. Seventeen years later the trade in live animals was forced to move north to the open space of Islington, due to the frequency of injuries and deaths caused by wayward cattle stampeding through the narrow streets of the City. And in 1868, the Meat Market at Smithfield formally opened as the London Central Meat Market in new permanent buildings designed by the famous City Architect, Sir Horace Jones.

And it is to this monument of Victorian vision and practicality that I am heading; its ornamental coloured cast iron as familiar to me as the dome of the Old Bailey, which peeks out from the periphery.

The market is sleepy and the workers have gone – the forgotten joke will have to wait for another night. Discarded takeaway cups are filling with rain and the litter from a night of work plasters the sodden streets. Wooden pallets are packed away, and lights within start to dim, as yawns set in. But not everyone is closing down, the day butchers are ready and waiting for custom.

At Smithfield Butchers a typical day starts at five am, with orders prepared for the pubs and hotels, with deliveries and shop displays and, of course, with “the breaking down” – dividing carcasses into those recognisable cuts of meat. This to me is a male world. A man is never without a hatchet or a knife, or a lump of meat, working skilfully amidst blood and bone and flesh, carving to extract the perfect cut. This is a world of affable men, natural storytellers whose banter is as rich and as succulent as a belly of pork, a world where birth names are replaced by nicknames.

Trevor Chelsea (or “Chels” as he is known – “because I support Chelsea”) is no exception. He has worked at the market for twenty-five years now, and I used to pass him and his colleagues as I made my daily way along Charterhouse street, the “hello” to the men at Crosby’s a natural ritual. They had been there since 1971, a bit of a landmark, always there and always would be there, I thought. But one compulsory purchase by the railways later, and the butchers moved to the west side of the market, leaving a yawning gap where they used to be.

“There was no time for a celebration or a quiet drink with your memories,” says Trevor, “it was a Bank Holiday, I remember, we packed up on the Friday and were in the new premises on the Monday. We had orders to fill and we got on with it.

The market has changed a lot since I started twenty-five years ago. A lot of business is done behind closed doors now, and all the characters are leaving or have left. In those early days, there was a real hustle and bustle, lots of laughing and joking, like a proper market, like Petticoat Lane. Loads of shouting.

It was the camaraderie,” he continues. “If I was to leave tomorrow, that’s what I’d take with me. And the laughs. You had to – In the early days my shift started at two am and went on till two pm. In winter it was freezing, hands had chilblains, it was real hard work, and those winters seemed colder then, maybe because we were outside all the time. But joking around kept you warm – kept your spirits up.

The rules and regulations were unwritten then, but you always knew what line not to cross. It was about what you could get away with. We used to cut off rabbit heads and nail ‘em to the front doors of customers who hated rabbit! Joe Pasquale used to work down here too – he liked to put a chicken on his head and run around. Teddy Lynch too – the brother of the entertainer Kenny Lynch – he was the first black man down here to be a bummaree,” and I must have looked quizzical because he added, “You know the barrow boys who load the meat and carcasses for the customer. They were the only ones who had the right to carry meat in the market. When I started there were about fifteen hundred bummarees – now there’s five.”

And Trevor leads me inside to look at the photographs on the wall, the photos of these “barrow boys”. And yet I see no boys, just men over fifty, the hard toil etched into their faces, of a working life that starts when most are asleep, and ends as daylight ferociously erupts across the city skyline.

“Him there, sitting on the stone,” says Trevor, pointing to an old man, “well that’s “Disley” – when he retired he had no one left. All his family had died, so he just came back down here and sat and watched. And that one there, that’s “Treacle” – they called him that because he had sticky fingers. You couldn’t leave meat around when he was about. And that one, him with the glasses, that’s Pat Crosby – brought up in a workhouse. Number D12. He still works. And him there, with the bugle, that’s Johnny Green, he played the Last Post the day the market died.” (The day the market temporarily closed in the mid-nineties to bring it up to EU food safety regulations).

“So did you always want to be a butcher?” I ask.

“No, at first I was a signwriter in Queensway for seven months, and it seemed like I wrote the same word for seven months! It drove me mad, so I left. But there was a recession and the only job I saw advertised was for an experienced butcher, so I went for it – told ‘em I’d worked as a butcher for a year. They found me out when they sent me to the fridge to get something – hadn’t got a clue what they were on about. But they kept me on and trained me. And I’m still here today. Cold and hungry, as we say.”

Treacle

Disley

Pat Crosby

Trevor

Johnny Green

Black and white portraits copyright © Chris Clunn

Colour photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

You may also like to read about

Ivor Robins, Fruit & Vegetable Purveyor