Mud God’s Discoveries 3

For many people the Thames is a sacred river populated by diverse gods, as mudlark Steve Brooker has discovered from all the offerings that he finds deposited in the mud, representative of the religious beliefs amongst the immigrant cultures of contemporary London. “Ever since I started, I’ve found thousands of them,” Steve told me, suggesting that the sub-aquatic spiritual universe of the Thames must be a crowded place where immortals cohabit side by side. “Woolwich, Bermondsey and Rotherhithe are very big on Indian offerings,” added Steve helpfully, “whereas I find Chinese artifacts at Silvertown.”

Although Steve is not a religious person, these objects exert a powerful fascination upon him. When he is alone on the mud, scouring the water’s edge in the dawn mist and he discovers a religious offering, then Steve recognises a personal sense of awe in the human credulity which led to the deliberate placing of these offerings in the river with the expectation of a particular result.

Instead of fairies at the bottom of his garden, Mud God Steve presides over a large community of deities from the Thames, and amulets too – all artifacts contrived to evoke benign spirits. But when Steve finds Voodoo dolls impaled with needles or vials wrapped in paper with obscure texts including the word “Lucifer,” then he leaves these strange offerings where he finds them in the river. “I don’t believe it, but I do have a healthy respect for it,” he admitted Steve warily. Once he came within three feet of being hit by an effigy, when at low tide the owner threw it with considerable heft to reach the water, narrowly missing knocking Steve for six. “They are just for luck – but I could have been killed by an offering!” declared Steve in affront, widening his eyes at the absurdity of it.

An invitation to examine some “Roman” pots at Woolwich led Steve on an especially muddy episode, which revealed hundreds of terracotta ghee pots (resembling Roman lamps) associated with the Indian festival of Diwali, when traditionally these lamps are set adrift upon the Ganges – the Thames in this instance standing in for the sacred river among London Hindus. Another common find are square metal plates incised with designs, these “yantras” are talismans to avert misfortune.

Most fascinating to Steve are the many modest silk bundles he finds upon the shore bound up carefully in red thread, containing offerings of seeds and sweet corn and coins. Also, sometimes wrapped up and tied in red thread are padlocks and glass vials containing fluid enfolded in texts written upon waxed paper, and the significance of the red thread especially perplexes him. “It means something to someone,” he mused.

“Always collect any coconut you see in the Thames,” Steve advised me – especially if it has been drilled and resealed, because these commonly contain offerings, which sometimes may be of value. Naturally, gold is the offering of greatest worth and Steve once found a lump of gold wrapped up in lead – lead and gold being two materials often combined in religious offerings – another source of enigma.

Many of the effigies in the river are cheap mass-produced objects, purely for the purpose of sacrifice, yet the human significance placed up these things gives them emotional value and meaning for Steve. Although occasionally, extraordinary sculpted items also turn up like the exquisite bronze head below which has its own presence and is believed to be of African origin.

There is a collective mystery to these objects that do not give up their secrets easily, and Steve feels obligated to provide a safe home for them all – in the private hope that one day they will speak to him. “I’d like to be a Buddhist,” he confessed to me, with the rogueishly appealing smile that is his signature,“but I think I’m too nasty!’

Clay lamps used by Hindus in the festival of Diwali – filled with ghee and set alight, they drift off across the water.

Yantras, a talismans to ward off evil.

Fine bronze head believed to be of African origin.

Steve Brooker’s series MUDMEN continues on History and you can find out more from his website www.thamesandfield.co.uk

You may like to catch up with

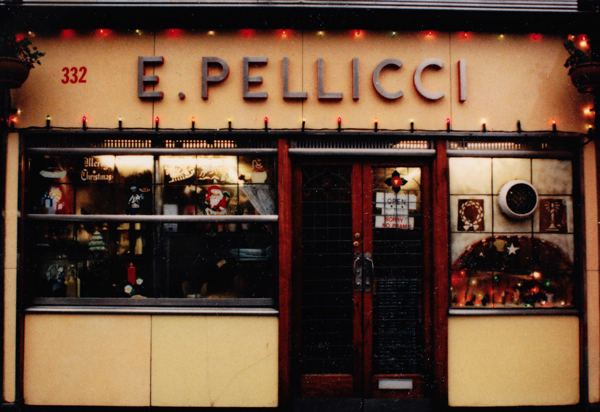

Pellicci’s Collection

This is Lucinda Rogers‘ drawing of E.Pellicci in the Bethnal Green Rd, London’s most celebrated family-run cafe, into the third generation now and in business for over a century – and continuing to welcome East Enders who have been coming for generations to sit in the cosy marquetry-lined interior and enjoy the honest, keenly-priced meals prepared every day from fresh ingredients.

E.Pellicci is a marvel. It is so beautiful it is listed, the food is always exemplary and I every time I come here I leave heartened to have met someone new.

I found Lucinda Rogers’ drawing on the wall in one of the small upper rooms that now serves as an informal museum of the history of the cafe, curated by Maria Pellicci’s nephew – Toni, a bright-eyed Neapolitan, who has been working here since he left school in Lucca in Tuscany and came to London in 1970. He led me up the narrow staircase, opened the door of the low-ceilinged room and with a single shy gesture of his arm indicated the family museum. Toni has lined the walls with press cuttings, photographs and all kinds of memorabilia, which tell the story of the ascendancy of Pellicci’s, attended by a few statues of saints to give the pleasing aura of a shrine to this cherished collection.

Primo Pellici began working in the cafe in 1900 and it was here in these two rooms that his wife Elide brought up his seven children single-handedly, whilst running the cafe below to keep the family after her husband’s death in 1931. Elide is the E.Pellicci whose initial is still emblazoned in chrome upon the primrose-hued vitroglass fascia and her portrait remains, she and her husband counterbalance each other eternally on either side of the serving hatch in the cafe. In 1921, Nevio senior was born in the front room here. He ran the cafe until his death in 2008, superceded as head of the family business today by his wife Maria who possesses a natural authority and charisma that makes her a worthy successor to Elide.

As I sat alone in the quiet of the room, leafing through the albums, surrounded by the walls of press coverage, Maria came upstairs from the kitchen to join me. She pointed out the flat roof at the rear where her former husband Nevio played as a child. “He was very happy here,” she assured me with a tender smile, standing silently and casting her eyes between the two empty rooms – sensing the emotional presence of the crowded family life that once filled in this space that is now a modest store room and an office. Maria and Nevio brought up their children in a terraced house around the corner in Derbyshire St, and these days Toni goes round each morning early to pick her up from there, before they start work around six at the cafe she runs with her son Nevio and daughter Anna.

Pellicci’s collection tells a very particular history of the twentieth century and beyond – of immigration, of wars, of coronations and gangsters too. But, more than this, it is a history of wonderful meals, a history of very hard work, a history of great family pride, and a history of happiness and love.

Primo Pellicci still presides upon the cafe where he started work in 1900.

Primo’s children, Nevio and Mary Pellicci, 1930.

Pellicci’s wartime licence issued to Elide Pellicci in 1939 by the Ministry of Food.

Pellicci’s paper bag issued to celebrate the Coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953 – note the phone number, Bishopsgate 1542.

Mary and Maria Pellicci, Trafalgar Sq, 1963.

Nevio junior, aged seven, skylarking outside the house in Derbyshire St with pals Claudio and Alfie.

Nevio senior and Toni, 1980.

Pellicci’s customers in 1980.

Nevio senior, 1980.

Nevio and Toni.

Christmas card from Charlie Kray, 1980.

Nevio junior and Nevio senior.

George Flay’s portrait of Nevio Junior, 2006. See more at www.artofflay.com

George Flay’s montage of the world of Pellicci’s.

Nevio Senior, 2005

Salvatore Zaccaria, known as Toni, keeper of Pellicci’s collection.

You may also enjoy reading

Leila’s Shop Report

Every Monday night, Leila McAlister goes to New Covent Garden Market in Nine Elms in to buy fruit and vegetables, and when I arrived at her shop on Tuesday morning, she had just finished packing up the weekly vegetable boxes that she delivers to her customers in the neighbourhood. The whole place was filled with enough spellbinding fragrances and astounding vivid colours of fresh Spring produce to lift the spirits of the saddest March day.

“At the end of Winter when you feel you are living in a black and white film, you need to eat lots of oranges!” declared Leila authoritatively, with a delighted smile – standing in her blue twill jacket amongst the stacks of boxes of oranges from Sicily that were just a fraction of her exciting night’s haul which she had driven back to Arnold Circus in the dawn.

As an adult in the thrall of a passion for fresh vegetables, Leila’s Shop gives me a comparable thrill to that I once received as a child entering a sweet shop, I really want to eat everything – from the humble varieties of English potatoes to the exotic delicacies from the Mediterranean. Fortunately, Leila has a liberal policy of allowing her customers to taste anything that can be consumed raw. You do not have to drop a heavy hint, you simply have to ask, “What’s this?” in a leading tone and usually a leaf or a slice will be forthcoming.

Among the crates of citrus from Italy were unwaxed leafy lemons and Moro, Tarocco and Sanguinello blood oranges. And in response to my query about the respective varieties, Leila seized the opportunity immediately to slice up a couple with a sharp knife to reveal the juicy ruby-red flesh, and we were able to savour the relative qualities of the Sanguinello and the Moro – the Sanguinello possessing a deep, almost pomegranate flavour with a strong citrus kick, while the Moro orange was a lighter, more scented fruit. We stood in silence for a moment of contemplative pleasure, with our mouths full of orange, as momentarily the spirit of the Mediterranean made its presence felt in Shoreditch.

Also from Italy, Leila has the most spectacular radicchios I ever saw – Castello Franco, a pale yellow rose-shaped plant and Tardivo, a purple bud-shaped plant – both available now in very limited supplies for a short season, through the markets of Verona. It is difficult to imagine a more delicious Spring salad leaf than these and I love to eat them with a simple dressing of lemon juice and olive oil, but Leila told me that the Italians, for whom bitter leaves are a national passion, like to grill them. These varieties are highly regionalised, and by law Tardivo can only be grown in the region around Traviso. “It’s a serious business in Italy,” confirmed Leila, casting her eyes affectionately upon her astonishing display of crisp yellow and purple leaves that cause her customers to gasp in wonder, and which I have seen nowhere else in London.

Wild English garlic is in season now and Leila buys bags of their smooth green leaves from traders at the market who have been out foraging to make some extra cash. She was quite surprised when I admitted that I like to put these pungently flavoured leaves raw into my ham sandwiches, because she prefers to braise them and add them to pasta or risotto, recounting their success as an unexpected addition in Bechamel sauce to liven up cauliflower cheese.

From nibbling these sharp green leaves, we moved on to thin peppery slices of French black radish, a vegetable grown with such loving care to the regular size and shape of salami. “With a lemon dressing, capers and chopped parsley, it would be heaven,” speculated Leila, her eyes glazing over in a day dream. Next we tried Jerusalem artichokes raw, at Olha’s suggestion, who informed us that they were known as “underground pears” in her native Ukraine, and surprisingly they do possess an attractive chestnut flavour. Since it was time for admissions, Leila revealed they were called “fartychokes” in her family – “We used to die laughing waiting for the farting to begin!” she confessed, rolling her eyes in happy reminiscence, and she confirmed that artichoke soup will be on the menu at Leila’s Cafe this weekend.

Yet we had only begun to explore the range of what is at its best this week. I must leave it to you to go along and try the forced rhubarb, the purple sprouting, the leeks, the fennel, the cabbages, the creamy avocados from Malaga and all the other goodies that are available now, as Spring moves inexorably North through Europe from the Mediterranean, encouraging new life in the fields, and bringing us the first crops of the year.

I used to have an eighty-four year old friend with whom I stayed in her apartment on the Upper West Side for many years, whenever I visited Manhattan. “If only they would invent something new to eat!” she used to lament endlessly in a humorous tone, as one of the trials of her advanced years. I wish I could have taken her to Leila’s Shop, because she would have discovered plenty of delicious things to inspire her appetite, not “new” at all – but simply Leila’s pick of the very best that is in season.

Leila’s weekly vegetable boxes are available for delivery throughout Shoreditch, Dalston, London Fields, Bethnal Green, Spitalfields and Whitechapel.

Sanguinello – blood oranges from Sicily.

Grape hyacinths.

Market day at Leila’s Shop.

Cabbages.

Forced Rhubarb.

Black French Radishes.

The bandstand at Arnold Circus.

Sicilian lemons.

Leeks.

Fennel.

Garlic.

Jerusalem Artichokes.

Corner table at Leila’s Cafe

English Daffodils.

Sage, Rosemary and Thyme.

Spring sunlight at Leila’s Cafe.

Castello Franco and Tardivo, radicchio from Northern Italy.

Green Irises

Paintings copyright © Olha Pryymak

You like to read about

Bryan Edwards, Pawnbroker

This dapper gentleman in the elegantly understated suit and tie, with the immaculately combed silver hair and naturally distinguished features is Bryan Edwards, who in 1985 acquired Attenborough Jewellers in the Bethnal Green Rd – the largest East End Pawnbroker, established in 1892. You might assume Attenborough’s was the last vestige of a former world of poverty – even a relic of another time – but you would be completely wrong because pawnbroking is a growth industry that is booming in the current financial climate, with each recession providing further opportunity for growth.

Whereas once the pawnbroker served only the poor, now members of all social groups find their way into Bryan’s modern pawnshop with its smart leather couch and air of being an upmarket bureau de change. “We’ve had a lot of people from the City in here,” confided Bryan proudly to me as I enjoyed a tour of his splendid facilities, without any trace of the dinginess that is associated with old-school pawnbroking in the popular imagination.

“Just after the war, there were only a hundred and forty pawnbrokers left in this country,” revealed Bryan – a former President and member of the Council of the National Pawnbrokers’ Association for twenty-seven years – widening his eyes in concern at the thought of those dark days. “We operated under a lot of financial restrictions until 1985 when the Consumer Credit Act of 1974 became law, and that gave us more scope. And now there are over twelve hundred pawnbrokers nationwide,” he continued, with a modest grin of satisfaction at the collective tenacity and prudence of those fellow members of his own industry who have proved themselves survivors through the thick and thin of the post-war years. “We’ve seen some changes!” he declared with the understated swagger of an old trouper.

“In 1985, the limit on lending went from fifty pounds to fifteen thousand in twenty-four hours,” he recalled, his eyes gleaming in retrospective delight, “And when the recession of the nineteen nineties kicked in, that was when it really began to grow and expand. We had people who couldn’t pay their mortgages and City executives coming in.” Adding for effect, “We kept calling up the bank and asking them to send over more money!” he said, to convey the sense of carnival at this glorious moment in the history of pawnbroking.

Bryan’s father started the family business as a jeweller in King’s Cross in 1944 and ran it until an unexpected illness in 1958. “In three years, I had to take over and run the business. I was thrown in at the deep end.” Bryan explained to me, introducing the account of his entire lifetime in the profession in which he has proved such an outstanding success. Counterbalancing Bryan’s modern pawnshop entered by the door on the right hand side of Attenborough’s, is the traditional jeweller’s entered through by the door on the left hand side. Approximately fifteen per cent of the items brought in through the right hand door as security for loans get sold through the left hand door when their owners default on their debt, Bryan told me. The average loan is between five and and fifteen thousand pounds, with jewellery as the most common form of security and approximately five months as the average pledge, I learnt.

“Some people are just not capable of managing their finances. They don’t budget and they overspend.” Bryan admitted reluctantly with a frown of disappointment, as if he felt personally let down. “But we do everything we can not to foreclose because it’s not in our interest to sell a customer’s goods since we lose a customer. Because we are a family business, we always help out if people are in difficulties and we bend over backwards to help those who are in real need.” he said, clasping his hands in concern and speaking more like an altruist than a businessman. His bold confidence reflecting the fact that the banking crisis and consequent dearth of credit and loans has been good news for the pawnbroking industry, enabling Bryan to expand his operations further – manifest in his sleek refitted pawn shop. “Our role is where the banks didn’t help. It’s like instant coffee, it’s instant money!” he enthused with a chuckle, spontaneously coining a slogan in his eagerness to give money away to people.

Bryan led me up an old staircase through a sequence of small matchboarded rooms to arrive at the office up above the shop, with a magnificent nineteenth century fireplace, shuttered sash windows and views up and down the Bethnal Green Rd. Here Bryan gave me his account of himself while his daughter sorted through filing, occasionally interjecting, “Just between ourselves” and “Don’t tell anyone this but…” into his monologue, much to her disapproval. I found it remarkable that he had retained such a trusting nature after more than half a century as a pawnbroker.

“I went to Las Vegas to a pawnbroker’s convention but I didn’t put a penny on anything, not even a fruit machine.” boasted Bryan Edwards, the model of abstention, giving unquestionably the most original excuse for a trip to Las Vegas I ever heard, yet revealing his humanity by confessing with reckless playfulness – leaning forward and whispering to me so that his daughter would not hear – “Just between ourselves, I did gamble once on a horse in the Grand National because it was called ‘Pawnbroker,’ and it lost!”

Brick Lane Market 3

This is John and his father Alf in the charismatic old shed they have just opened up beside the railway bridge in Brick Lane. Two stalwarts who have spent their working lives buying and selling all manner of commodities in the East End – Alf entered local lore when he bought a lion cub off a ship in the docks forty years ago and sold it at Club Row animal market, while his son John has always traded around Brick Lane.

“I used to to have the biggest railway arch here, then I was in Cheshire St and once I had the biggest yard in Bacon St.” he boasted, explaining that for the past six years he has lived in the tiny caravan nestled snugly at the rear of his shed. When you enter the tall red wooden doors leading off Brick Lane into the huge shack with a multiplicity of stalls and a tea stand, you enter John’s world where he sells “all and everything, from a-z.”

“Is this bric-a-brac or junk?” I ventured, casting my eyes around the ramshackle mixture filling the cavernous space, where Tom the weather-beatened and tanned sailor lurked in the shadows at the rear with his big black dog. Raising his brows at the impudence of my question, “It’s shabby chic!” John declared, twisting his stubbly features into the leery smirk of a showman – “’Shabby chic’ was invented in Brick Lane.”

“I used to come up here with my dad and it was like a day out. If you wanted something you could get it for pennies. This place is what Brick Lane was like twenty years ago,” he continued, introducing his personal view of the changing currents of the market. “Saturday is better for us than Sunday now,” he said,“People come to all the vintage clothes shops but I don’t know how they make any money. I reckon that’s why they call them ‘pop-up shops’ because they pop up and then pop off.”

Over a cuppa from the tea stall, I settled down to enjoy Alf’s lyrical stories of the old East End, of Spratt’s dog food, Twining’s Tea, Percy Dalton’s peanuts, and of the former magnificence of Wellclose Square and when Wilton’s Music Hall was a rag store, and of his poor old pet fox, and Quackers, his pet duck, that followed him around the streets. “I think it’s a more violent world now,” he confided in a whisper, “beyond Vallance Rd is a dangerous place with gangs and drug wars. I won’t go there.”

When John’s two sons arrived from school in their smart green uniforms, I asked them if they planned to continue trading here on Brick Lane but they both shook their heads in unison. “I want them to be traders in the stockmarket,” said John, accompanied by nods of enthusiasm from his boys, “I take them for walks around the Docklands and tell them which companies to work for.”

“You want them to be bankers?” I queried. “I want them to make money,” he confirmed, “A lot of successful people have come out of Brick Lane, Alan Sugar started round the corner and the old man used to sell records to Richard Branson.” And then, turning to his father, their eyes met in a moment of shared realisation. “Where did we go wrong?” he asked, raising his hands with a grimace of bewilderment.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Naseem Khan OBE, Friend of Arnold Circus

Behind this lyrical, quintessentially English image of a little girl surrounded by carnations in a cottage garden in Worcestershire lies an unexpected story – because this is Naseem Khan whose father was Indian and mother was German. They met in London and married in 1935 and Naseem was born in 1939. When the war came, they could not return either to India, which was in the early throes of partition, or Germany which was under the control of Adolf Hitler, and so they went to live in rural Worcestershire for the duration, where Naseem’s mother was able to maintain a discreet profile, concealing her true nationality and passing as French.

These were the uneasy circumstances of Naseem’s origin, and yet they granted her a unique vision of society which has informed her life’s work in all kinds of creative ways – including being Head of Diversity at the Arts Council and more recently Chair of the Friends of Arnold Circus, the group responsible for the rescue and sympathetic renovation of the neglected park and bandstand at the centre of the Boundary Estate last year.

Naseem’s father, Abdul Wasi Khan was a doctor from Seoni, the eldest of ten in a struggling family, who won an award from a foundation in Hyderabad to study in London where he completed a further three degrees qualifying as the highest level of surgeon, although as an Indian, discrimination prevented him practicing his expertise in this country at that time. Naseem’s mother, Gerda Kilbinger came to study English at a college in London, and her best friend at the language school was dating an Indian doctor who was “so handsome, so smart,” but when Gerda finally met this paragon who was to become her husband she exclaimed, “Ach, is that what the fuss is all about?” Gerda may have been initially unimpressed by Wasi’s diminutive stature, which matched her own, yet it was the first of his qualities that she noticed which unified the couple as a pair from the margins in British society.

“They were very concerned that I and my brother be accepted, and they thought the best way to achieve that was to send us to boarding school. But at Roedean, where Home Counties girls were sent – destined to be secretaries at the Foreign Office before they found a suitable young man to marry – I was like a fish out of water,” admitted Naseem, speaking softly yet with sublime confidence, and without any shred of resentment, “My best friends were a small group of Jewish girls.”

“At the end of the war, my mother got permission to go and find her parents in Germany and it was very shocking, the damage, despair and the demoralisation.” she recalled, “I was particularly impressed by my grandfather, a man of great integrity, and I would take my own children each year for open house on his birthday. He used to make a great soup, and members of the local football team and the mayor’s office would come. He would garden all Summer long in his allotment and do metalwork in the Winter. He had just a few good books and a few pieces of good furniture and I always liked that feeling, of having nothing superfluous.”

Blessed with a modest temperament and sharp intelligence, Naseem graduated from Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, and pursued a wide-ranging career as a journalist, including being among those who launched Notting Hill’s black newspaper The Hustler and becoming theatre editor at Time Out when the new experimental theatre erupted in Britain. Invited by the Arts Council to research aspects of immigrant culture, she left her job to write a report entitled “The Arts Britain Ignores,” a re-examination of what was considered as legitimate English culture, which became a cornerstone of policy and led to a further career for Naseem in policy-making. “It was an important period of recognition of difference, striving to find a world in which all sides are possible, contained and honoured.” said Naseem in quiet reflection.

For twenty-five years, Naseem lived in Hampstead and when her children George and Amelia finished university, she found that her marriage had evaporated. Separating on amicable terms with her husband and splitting the proceeds of the family house, she began a new life in the East End eleven years ago. “What I’d missed in Hampstead was diversity, a sense of community and dynamism,” she revealed with a weary smile, “And being closer to the Buddhist centre in the Roman Rd was a plus for me. When I first came to look at this terraced house beside Columbia Rd, it was Summer and the little garden was an oasis and I thought, ‘This is where I could put down my new life.’ – I knew this was where I wanted to be, although I didn’t realise it at the time. I wanted to be in a place of change.”

Over the last five years, as Chair of the Friends of Arnold Circus, Naseem has created a charity with over five hundred members dedicated to bringing together the diverse community of the Boundary Estate. While the renovation of the park – culminating in the joyous opening last Summer – has been the most visible aspect of the Friends’ work, all kinds of other projects including gardening and music-making continue throughout the year. “I think my particular skill is being able to create a space in which people with different skills and different outlooks can work together and achieve what they want to.” said Naseem, demonstrating her innate magnanimity while thinking out loud, “I am a connector and it means recognising the synergy by which different people can come together to create something new.”

Naseem’s work has contributed to a new sense of self respect and pride in the neighbourhood for the residents of the Boundary Estate. In this sense Naseem Khan’s work here is both a culmination of her personal journey informed by her parents’ experiences, while also continuing the ethos of Sir Arthur Arnold who built the Estate – in the authentic and radical tradition of social campaigners who have brought about real change for the people of the East End.

Naseem’s estimate of her achievement is simpler. “When you live a long time, you do a lot of things.” she said with a grin of self-effacing levity.

Read Naseem’s article about Sir Arthur Arnold Who is Arnold Circus?

Naseem’s grandmother Maria Kilbinger with Naseem’s mother Gerda and Aunt Elsa in 1916.

Naseem’s mother’s German school attendance card issued 1913.

Gerda & Wasi, newly married in 1935 in Edinburgh.

Naseem’s British identity card issued 1940.

Naseem with her father, aged eight, 1948.

Naseem’s family and neighbours in Worcestershire in 1951. Her mother Gerda stands in the centre with her father Wasi on the far right and her Uncle Mujtaba standing between them. Sitting in the centre is Naseem’s half-sister Shamim. Standing on the far left is Harold Tolly, the baker, with his wife Myfanwy, the midwife, seated on the right holding Anwar on her lap.

Naseem and her brother Anwar, 1952.

Naseem at Oxford, Lady Margaret Hall, 1958

The Temptation of Buddha, Naseem is the dancer in front on the right.

At a year’s Buddhist retreat at the Upaya Zen Centre in New Mexico, 2007.

Naseem Khan OBE, Chair of the Friends of Arnold Circus

Learn more at www.naseemkhan.com and www.foac.org.uk

At Liverpool St Station

When I was callow and new to London, I once arrived back on a train into Liverpool St Station after the last tube had gone and spent the night there waiting for the first tube next morning. With little money and unaware of the existence of night buses, I passed the long hours possessed by alternating fears of being abducted by a stranger or being arrested by the police for loitering. Liverpool St was quite a different place then, dark and sooty and diabolical – before it was rebuilt in 1990 to become the expansive glasshouse that we all know today – and I had such an intensely terrifying and exciting night then that I can remember it fondly now.

Old Liverpool St Station was both a labyrinth and the beast in the labyrinth too. There were so many tunnels twisting and turning that you felt you were entering the entrails of a monster and when you emerged onto the concourse it was as if you had arrived, like Jonah or Pinocchio, at the enormous ribbed belly.

I was travelling back from spending Saturday night in Cromer and stopped off at Norwich to explore, visiting the castle and studying its collection of watercolours by John Sell Cotman. It was only on the slow stopping-train between Norwich and London on Sunday evening that I realised my mistake and sat anxiously checking my wristwatch at each station, hoping that I would make it back in time. When the train pulled in to Liverpool St, I ran down the platform to the tube entrance only to discover the gates shut, closed early on Sunday night.

It was late August and I was in my Summer clothes, and although it had been warm that day, the night was cold and I was ill-equipped for it. If there was a waiting room, in my shameful fear I was too intimidated to enter. Instead, I sat shivering on a bench in my thin white clothes clutching my bag, wide-eyed and timid as a mouse – alone in the centre of the empty dark station and with a wide berth of vacant space around me, so that I could, at least, see any potential threat approaching.

Dividing the station in two were huge ramps where postal lorries rattled up and down all night at great speed, driving right onto the platforms to deliver sacks of mail to the awaiting trains. In spite of the overarching vaulted roof, there was no sense of a single space as there is today, but rather a chaotic railway station criss-crossed by footbridges, extending beyond the corner of visibility with black arches receding indefinitely in the manner of Piranesi.

The night passed without any threat, although when the dawn came I felt as relieved as if I had experienced a spiritual ordeal, comparable to a night in a haunted house in the scary films that I loved so much at that time. It was my own vulnerability as an out-of-towner versus the terror of the unknowable Babylonian city, yet – if I had known then what I knew now – I could simply have walked down to the Spitalfields Fruit & Vegetable Market and passed the night in one of the cafes there, safe in the nocturnal cocoon of market life.

Guilty, and eager to preserve the secret of my foolish vigil, I took the first tube to the office in West London where I worked then and changed my clothes in a toilet cubicle, arriving at my desk hours before anyone else.

Only the vaulted roof and the Great Eastern Hotel were kept in the dramatic transformation that created the modern station, sandwiched between new developments, and the dark cathedral where I spent the night is gone. Yet a magnetism constantly draws me back to Liverpool St, not simply to walk through, but to spend time wondering at the epic drama of life in this vast terminus where a flooding current of humanity courses through twice a day – one of the great spectacles of our extraordinary metropolis.

Shortly after my night on the station experience, I got a job at the Bishopsgate Institute – and Liverpool St and Spitalfields became familiar, accessed through the tunnels that extended beyond the station under the road, delivering me directly to my workplace. I noticed the other day that the entrance to the tunnel remains on the Spitalfields side of Bishopsgate, though bricked up now. And I wondered sentimentally, almost longingly, if I could get into it, could I emerge into the old Liverpool St Station, and visit the haunted memory of my own past?

A brick relief of a steam train upon the rear of the Great Eastern Hotel.

Liverpool St Station is built on the site of the Bethlehem Hospital, commonly known as “Bedlam.”

Archive images copyright © Bishopsgate Institute