Tony Hall, Photographer

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Bonner St, Bethnal Green

Tony Hall (1936-2008) would not have described himself as a photographer – his life’s work was that of a graphic designer, political cartoonist and illustrator. Yet, on the basis of the legacy of around a thousand photographs that he took, he was unquestionably a photographer, blessed with a natural empathy for his subjects and possessing a bold aesthetic sensibility too.

Tony’s wife Libby Hall, known as a photographer and collector of dog photography, gave her husband’s photographs to the Bishopsgate Institute where they are held in the archive permanently. “It was an extraordinary experience because there were many that I had never seen before and I wanted to ask him about them,” Libby confessed to me, “I noticed Tony reflected in the glass of J.Barker, the butcher’s shop, and then to my surprise I saw myself standing next to him.”

“I was often with him but, from the mid-sixties to the early seventies, he worked shifts and wandered around taking photographs on weekday afternoons,” she reflected, “He loved roaming in the East End and photographing it.”

Born in Ealing, Tony Hall studied painting at the Royal College of Art under Ruskin Spear. But although he quickly acquired a reputation as a talented portrait painter, he chose to reject the medium, deciding that he did not want to create pictures which could only be afforded by the wealthy, turning his abilities instead towards graphic works that could be mass-produced for a wider audience.

Originally from New York, Libby met Tony when she went to work at a printers in Cowcross St, Clerkenwell, where he was employed as a graphic artist. “The boss was member of the Communist Party yet he resented it when we tried to start a union and he was always running out of money to pay our wages, giving us ‘subs’ bit by bit.” she recalled with fond indignation, “I was supposed to manage the office and type things, but the place was such a mess that the typewriter was on top of a filing cabinet and they expected me to type standing up. There were twelve of us working there and we did mail order catalogues. Tony and the others used to compete to see who could get the most appalling designs into the catalogues.”

“Then Tony went to work for the Evening News as a newspaper artist on Fleet St and I joined the Morning Star as a press photographer.” Libby continued,” I remember he refused to draw a graphic of a black man as a mugger and, when the High Wizard of the Klu Klux Klan came to London, Tony draw a little ice cream badge onto his uniform on the photograph and it was published!” After the Evening News, Tony worked at The Sun until the move to Wapping, using this opportunity of short shifts to develop his career as a graphic artist by drawing weekly cartoons for the Labour Herald.

This was the moment when Tony also had the time to pursue his photography, recording an affectionate chronicle of the daily life of the East End where he lived from 1960 until the end of his life – first in Barbauld Rd, Stoke Newington, then in Nevill Rd above a butchers shop, before making a home with Libby in 1967 at Ickburgh Rd, Clapton. “It is the England I first loved …” Libby confided, surveying Tony’s pictures that record his tender personal vision for perpetuity,”… the smell of tobacco, wet tweed and coal fires.”

“He’d say to me sometimes, ‘I must do something with those photographs,'” Libby told me, which makes it a special delight to publish Tony Hall’s pictures.

Children with their bonfire for Guy Fawkes

In the Hackney Rd

“I love the way these women are looking at Tony in this picture, they’re looking at him with such trust – it’s the way he’s made them feel. He would have been in his early thirties then.”

On the Regent’s Canal near Grove Rd

On Globe Rd

In Old Montague St

In Old Montague St

In Club Row Market

On the Roman Rd

In Ridley Rd Market

In Ridley Rd Market

In Artillery Lane, Spitalfields

Tony & Libby Hall in Cheshire St

Tony & Libby Hall in Cheshire St

Photographs copyright © Estate of Libby Hall

Images Courtesy of the Tony Hall Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read

Billy & Charley’s Shadwell Shams

Tickets are available for my tour throughout August & September

William Smith & Charles Eaton – better known as Billy & Charley – were a couple of Thames mudlarks who sold artefacts they claimed to have found in the Thames in Shadwell and elsewhere. Yet this threadbare veil of fiction conceals the astonishing resourcefulness and creativity that these two illiterate East Enders demonstrated in designing and casting tens of thousands of cod-medieval trinkets – eventually referred to as “Shadwell Shams” – which had the nineteenth century archaeological establishment running around in circles of confusion and misdirection for decades.

“They were intelligent but without knowledge,” explained collector Philip Mernick, outlining the central mystery of Billy & Charley, “someone told them ‘If you can make these, you can get money for them.’ Yet someone must also have given them the designs, because I find it hard to believe they had the imagination to invent all these – but maybe they did?”

Working in Rosemary Lane, significantly placed close to the Royal Mint, Billy & Charley operated in an area where small workshops casting maritime fixtures and fittings for the docks were common. Between 1856 until 1870, they used lead alloy and cut into plaster of paris with nails and knives to create moulds, finishing their counterfeit antiquities with acid to simulate the effects of age. Formerly, they made money as mudlarks selling their Thames discoveries to a dealer, William Edwards, whom Billy first met in 1845. Edwards described Billy & Charley as “his boys” and became their fence, passing on their fakes to George Eastwood, a more established antiques dealer based in the City Rd.

Badges, such as these from Philip Mernick’s collection, were their commonest productions – costing less than tuppence to make, yet selling for half a crown. These items were eagerly acquired in a new market for antiquities among the middle class who had spare cash but not sufficient education to understand what they were buying. Yet many eminent figures were also duped, including the archaeologist, Charles Roach Smith, who was convinced the artefacts were from the sixteenth century, suggesting that they could not be forgeries if there was no original from which they were copied. Similarly, Rev Thomas Hugo, Vicar of St Botolph’s, Bishopsgate, took an interest, believing them to be medieval pilgrims’ badges.

The question became a matter for the courts in August 1858 when the dealer George Eastwood sued The Athenaeum for accusing him of selling fakes. Eastwood testified he paid £296 to William Edwards for over a thousand objects that Edwards had originally bought for £200. Speaking both for himself and Charley, Billy Smith – described in the record as a “rough looking man” – assured the court that they had found the items in the Thames and earned £400 from the sale. Without further evidence, the judge returned a verdict of not guilty upon the publisher since Eastwood had not been named explicitly in print.

The publicity generated by the trial proved ideal for the opening of Eastwood’s new shop, moving his business from City Rd to Haymarket in 1859 and enjoying a boost in sales of Billy & Charley’s creations. Yet, two years later, the bottom fell out of the market when a sceptical member of the Society of Antiquaries visited Shadwell Dock and uncovered the truth from a sewer hunter who confirmed Billy & Charley’s covert means of production.

As they were losing credibility, Billy & Charley were becoming more accomplished and ambitious in their works, branching out into more elaborate designs and casting in brass. It led them to travel beyond the capital, in hope of escaping their reputation and selling their wares. They were arrested in Windsor in 1867 but, without sufficient ground for prosecution, they were released. By 1869, their designs could be bought for a penny each.

A year later, Charley died of consumption in a tenement in Wellclose Sq at thirty-five years old. The same year, Billy was forced to admit that he copied the design of a badge from a butter mould – and thus he vanishes from the historical record.

It is a wonder that the archaeological establishment were fooled for so long by Billy & Charley, when their pseudo-medieval designs include Arabic dates that were not used in Europe before the fifteenth century. Maybe the conviction and fluency of their work persuaded the original purchasers of its authenticity? Far from crude or cynical productions, Billy & Charley’s creations possess character, humour and even panache, suggesting they are the outcome of an ingenious delight – one which could even find inspiration for a pilgrim’s badge in a butter mould. Studying these works, it becomes apparent that there is a creative intelligence at work which, in another time, might be celebrated as the talent of an artist or designer, even if in Billy & Charley’s world it found its only outlet in semi-criminal activity.

Yet the final irony lies with Billy & Charley – today their Shadwell Shams are commonly worth more than the genuine antiquities they forged.

You may also like to read about

Maxie Lea MB, Football Referee

Tickets are available for my tour throughout August & September

Maxie Lea – Ready for training!

At the top of Brick Lane, there was once a nest of densely populated streets where a group of young boys became friends in the nineteen thirties and although the topography has changed beyond all recognition, their friendship remains alive today. Max Lea was one of those who shared in the lively camaraderie engendered at the Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys’ Club, which was based nearby in Chance St, where the boys met each evening to let off steam and enjoy high jinks, while escaping their crowded homes.

“Maxie,” as he is commonly known, became a member in 1941 and then a club manager in 1947, a post that he held until it closed in 1989. For many years Maxie organised the annual reunions and, in 2000, the Queen gave him an MBE for his stalwart devotion to the heroic boys’ club. Of diminutive stature and playful by nature, with his pebble glasses and exuberant humour, Maxie was always a popular figure, but his experiences at the Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys’ Club encouraged his gregarious personality and his respect for justice – finding equal expression in the sporting life he has pursued both as player and as referee.

I was born in the Royal London Hospital Whitechapel on 29th June 1930 as a twin, with a blue baby that died after eight hours. My parents lived at 265 Brick Lane in a small grocery shop. My mother’s family came from Lodz in Poland and they had a tailoring business in Plumbers Row, Stepney. My father’s family were from Russia but I don’t know where, he came with his family to Portsmouth in the nineteen twenties. They met through friends. My father travelled up from Portsmouth and they got married and lived on Brick Lane where he started a tailoring business in the house. Mum ran the grocery shop, which was opposite Gossett St. There were five children, we all slept in the two upstairs rooms and we kept ourselves together, we were never short of food.

At nine, I was evacuated, at first to Soham and then to Stoke Hammond for eighteen months. The thing that always comes back to me was when we had a big snowfall, I was walking to school with my sister and the next thing she said was, “Where are you?” I fell into a ditch. Life was good, quite peaceful and I played football and cricket with the other boys. It taught me a lot about friendship.

At thirteen years, I came back for my Bar Mitzvah but on the day of the service I had Quinsy, a swelling of the throat. I was lying in bed and I could hardly speak. I heard my mother and father downstairs, saying,“What are we going to do?” At that moment, it burst! We went along but I could only say a portion of the Torah – just the pages in the front – and after that I went back to bed.

Then, at fourteen, I left school and, as my brother was a pastry cook, I decided I was going to do the same and I went to work at Joe Lyons in Coventry St, Piccadilly. Going to work so early in the mornings, the good-time girls used to take my arm and say “Come with me.” But I said, “I’m on my way to work!” I didn’t hardly know what it was all about – I was just a little fella.

In 1941, I joined the Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys Club in Chance St. Until then, the only holiday I ever had was Southend, staying in Mrs Lewis’ boarding house for a week while my father travelled back and forth to work each day. Joining the club, I got to go on camps and Harry Tichener, the club manager known as “T,” became like a second father to me. He was a photographer by profession and an Associate of the Royal Photographic Society. At fourteen, I joined the committee as a junior officer. It built a life of comradeship for us. And it taught me how to deal with others and how to talk to people. It taught me management, that you don’t say, “Oi, Can you do this?” You say, “Can you please help me?”

I moved out of Brick Lane in 1960, when they pulled the shop down and offered us a place in Vallance Rd. But it was under the railway, so we moved to Rostrevor Avenue instead and eventually to Stamford Hill. My mother ran the shop all this time and I lived with her until she died at seventy-seven in 1976. From being a pastry chef, I became a stock keeper for sportswear company and then I worked for Tower Hamlets Housing Office, staying until I retired in 1995. When I was working for Tower Hamlets, I used to deal with new properties and, one day, a lady came in to present the papers of 265 Brick Lane and my heart stopped. “What’s the matter?” she asked, and I said, “Before they pulled it down, I used to live at that number.”

Maxie has been back only twice to Brick Lane since 1960. “Each time, I went for walk and got lost,” he admitted to me with a crazy grin of self-parody, “but it’s just as mixed now as it ever was.” Yet although the streets are changed and the building in Chance St is gone long ago, Harry Tichener’s affectionate and beautiful photographs survive to witness the vibrant world of the Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys’ Club – which once offered an invaluable taste of freedom to so many young men from the East End.

Today, Maxie is in regular contact with the friends he made in Brick Lane in the nineteen thirties, and he lives now in an immaculate flat in Stanmore surrounded by trophies and certificates, commemorating his meritorious services to refereeing football matches. At first, I couldn’t quite understand the appeal of refereeing until Maxie confided, “As a player you only make acquaintances, but as a referee you make many more lasting friendships. It has given me a very fruitful and interesting life.”

Max enjoys a casual cigarette at age eleven, pictured here with Victor Monger, 1941.

Boat trip, Max raises his fingers to his chin in the centre left of the picture.

Camp Banquet, Max is on the far left.

On Herne Bay Sands, Max stands in profile on the right.

Looking down on Dover, Max is on the left of the group.

Max is in the chef’s hat with a pipe on the left of this picture.

Max is pictured doing the washing up on the left of the table.

Max is in the centre right, paddling with his pals, Stanley, Manny, Butch & Ken.

Max & Stanley go boating.

Treasure Hunt, Max is centre left beneath the tree.

The Treasure Hunt continues, Max is on the right.

A Human Pyramid with Max at the top.

Tea in the orchard 1942, Max sits on the right drinking a mug of tea.

Max peels the spuds at the centre of this picture.

Harold goes for breakfast while Paul & Max look on.

1950, Shackelford. Max, Roy & Albert get water.

Weekend Camp, Easter 1955. Max with his head in his pal’s lap.

France, 1959, Max at the centre of this group.

France 1959, Max is seen in profile, waving at the centre left of this picture.

France, 1959, Max is at the centre of this happy group.

Easter, 1955.

Weekend Course at Amersham, Max at the centre.

Hastings, 1957, Max and his scooter.

Max & pals at Middelkerne Beach.

In 2000, Max receives his MBE for services to the Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys’ Club.

Max Lea MBE –“The sporting life has kept me fit for all these years.”

Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys’ Club photographs by Harry Tichener ARPS

Portrait copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Read my other Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys Club Stories

At the Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys Club 86th Annual Reunion

At Eel Pie Island

Tickets are available for my tour throughout August & September

Even though Twickenham is a suburb of London these days, it still retains the quality of a small riverside town. The kind of place where a crowd forms to watch a crow eating a bag of crisps – as I observed in the High St, before I crossed the bowed footbridge over to Eel Pie Island.

This tiny haven in the Thames proposes a further remove from the metropolis, a leafy dominion of artists’ cabins, rustic bungalows and old boatyards where, at the overgrown end of the only path, I came upon the entrance to Eel Pie Island Slipway. Here, where there are no roads, and enfolded on three sides by trees and tumbledown shacks, a hundred-year-old boatshed over-arches a hidden slipway attended by a crowded workshop filled with an accretion of old tools and maritime paraphernalia.

For the past thirty years, this magnificent old yard has been run by Ken Dwan, where twelve men work – shipwrights, platers, welders, marine engineers and marine electricians – on the slipway and in the workshop. “We have all the skills here, “ Ken informed me, “and the older ones are passing it onto the younger ones. Everybody learns on the job.” One of just four yards left on the Thames, Ken has his order book full for the next year, busy converting barges into houseboats, and maintaining and repairing those already in existence which, by law, have to be surveyed every five years.

Like his brother John Dwan – the Lighterman I spent a day with once – Ken has worked on the river his whole life, earning a living and becoming deeply engaged with the culture of the Thames. Ken makes no apology to describe himself as a riverman and, as I discovered, the currents of this great watercourse have taken him in some unexpected directions.

“I started as an apprentice Waterman & Lighterman at fifteen. When the Devlin Report came out in 1967, all Lightermen had to be fully employed by lighterage companies, and I joined F.T.Everard & Sons. You got your orders over the phone the night before, and they sent you to collect and deliver from any of the docks between Hammersmith and Gravesend. We used to drive and row barges of every conceivable cargo – lamp black, palm oil, molasses, wool, petrol, sugar – I even moved a church once!

The work moved East as the docks quietened down and companies closed. Because of the Devlin Report, we had a domino effect whereby, when one company shut, everybody would join the next but there wasn’t enough work and so they shut too. But, as freemen of the Thames, we Lightermen were able to work in civil engineering. I worked on the building of the Thames Flood Barrier, and a lot went into the construction of Canary Wharf and the redevelopment of the Pool of London.

After that, I worked on the passenger boats, and I decided to buy one with a partner and we formed Thames Cruises – doing trips from Westminster to Gravesend. We started by buying other people’s cast-offs and we needed to repair them, so then we bought this place and I came up here while my partner ran the passenger boats. They still run from Lambeth. I found that if you have the facility, a lot of people want repairs and now most of our work is for other people. We also do a small amount of boat building and we provide a service of scattering of ashes on the river for the Asian community.

I did a lot of rowing years ago, I went to two Olympics as a single sculler, in 1968 and 1972. I won my Doggett’s Coat & Badge and was made a Queen’s Waterman, becoming the Queen’s Bargemaster for three years. My job was to move the crown in the State Coach from Buckingham Palace to Westminster for the Opening of Parliament. It dates back to the time when the safest way to travel was by water. They do suggest that the London streets are safer now than years ago, but you may wish to question that. I was Master of the Watermen’s Company from 2007/8, and now both my sons have got their Doggett’s Coat & badge and work on the river too.

I loved working around the Pool of London years ago, and, sometimes after work, I used to walk through Billingsgate Market late at night. There’d be be fish and ice everywhere, the atmosphere in that place was incredible. When we were out of work, we could get a tanner there for pushing the barrows of fish up the hill. My favourite place in London then was Tower Hill in the early morning, the escapologist on the corner trying to get out of the bag, and the old coffee shops where you could get steak and kidney pudding. When the big old tomato boats moored on the West side of London Bridge, the bridge would be full of people watching what was being moved around – it didn’t matter what time of year, people lined the bridge because there was always something different being unloaded. All the cranes were still working then and the place was hive of industry. It was a privilege to be part of it. For a fifteen year old, the London Docks was an adventure playground.

It’s never been hard getting out of bed and going to work. I still love going on the river seven days a week. It was never a job. It was an absolute pleasure. It was a life.”

When Ken visited Eel Pie Island as a fifteen year old apprentice Lighterman, he did not know that one day he would come back as master of the boatyard here. Yet today, as custodian of the slipway, he is aware of the presence of his former self – indicating to me the hull of a lighter that he worked on when it carried cargo which now he is converting to a houseboat. His sequestered boatyard is one of the few unchanged places of industry on the Thames, where the business of repairing old vessels that no other boatyard will touch is pursued conscientiously, using the old trades – where all the knowledge, skills and expertise that Ken Dwan once learnt in the London Docks is kept alive.

Ken Dwan, Waterman & Lighterman

A nineteenth century Dutch barge and Thames lighter of a hundred years ago.

“This barge, I worked on it when it moved cargo and now we are converting it into a palace!”

Ken Dwan – the Queen’s Bargemaster – stands at the centre, surrounded by fellow Watermen.

Looking across to the mainland and Twickenham church.

You may also like to read about

Dan Jones’ East End Portraits

Tickets are available for my tour throughout August & September

In recent years, Dan Jones has painted a magnificent series from different eras for his EAST END PORTRAITS. Many of these are well known but others less familiar, so you can click on any of the names to learn more about the subjects.

Police Constable James Stewart

Portraits copyright © Dan Jones

You may also like to take a look at

So Long, Terry O’ Leary

Tickets are available for my tour throughout August & September

Terry O’Leary died on 31st July aged sixty-four

Terry O’Leary 1960-2024

“For two years, I cared for my brother – who was diagnosed with HIV in 1987 – in his council flat, but after he died I couldn’t stay there because my relationship with him as his sister wasn’t recognised by the council, and that’s how I became homeless,” said Terry, speaking plainly yet without self-pity, as we sat on either side of a table in Dino’s Cafe, Spitalfields. And there, in a single sentence I learnt the explanation of how one woman, in spite of her intelligence and skill, fell through the surface of the world and found herself living in a hostel with one hundred and twenty-eight other homeless people.

Terry was a shrewd woman with an innate dignity and a lightness of manner too. She managed to be both vividly present in the moment and also detached – considering and assessing – though quick to smile at the ironies of life. She wore utilitarian clothing which revealed little of the wearer and sometimes she presented an apparently tentative presence, but when you met her sympathetic dark eyes, she revealed her strength and her capacity for joy.

No one could deny it was an act of moral courage, when Terry gave up her career as a chef to care for her brother at a time when little support or medication was available to those with AIDS, moving in with him and devoting herself fully to his care. Yet in spite of the cruel outcome of her sacrifice, Terry discovered the resourcefulness to create another existence, which allowed her to draw upon these experiences in a creative way, through her work as performer and teacher with Cardboard Citizens, the homeless people’s theatre company based in Spitalfields.

“I took what I could with me, the rest I left behind. I took photographs and personal things. You fill your car with your TV, records, books and all the rest of it – but then you find it can be quite liberating because you realise all that stuff is not important,” admitted Terry with a wry smile, recounting a lesson born out of necessity. In the Mare St hostel in Hackney, Terry stayed in her tiny room to avoid the culture of alcohol and drug-taking that prevailed, but instead she found herself at the mercy of the absurdly doctrinaire bureaucracy, “I remember the staff coming round and saying, ‘You have to remove one of the two chairs in your room because you’re only allowed to have one.'” Terry recalled, “You find you’re living in a universe where you can get evicted for having two chairs in your room,” she added with a tragic grin.

A few months after she came to the hostel, Cardboard Citizens visited to perform and stage workshops, permitting Terry to participate and make some friends – but most importantly granting her a new role in life. “I was hooked,” confided Terry, “What I liked about it was the opportunity to talk about our own experiences and how we can make a change. And the best part of it was when the audience became involved and got on stage.” Terry joined the company and described their aim to me as being to “give voice to the homeless oppressed and show the situations homeless people face.”

Inspired by the principles of theatrical visionary Augusto Boal, the company perform in homeless shelters and hostels, creating vital performances that invite audiences of the homeless to participate, addressing in drama the pertinent questions and challenges they face in life – all in pursuit of the possibility of change.

Terry’s role was central to the company, as mediator, bringing the audience to the play, and raising questions that articulated the discussion manifest in the drama. She carried it off with grace, becoming the moral centre of the performance. And it was a natural role for Terry, one she referred to as “Joker” – somebody who will always challenge – anchoring the evening with her sense of levity and quick intelligence, without ever admitting that she understood more than her audience. Though, knowing Terry’s story, I found it especially poignant to observe Terry’s measured equanimity, even when the drama dealt with issues of grief and dislocation that are familiar territory for her personally.

“You don’t have to accept things as they are. You can fight back,” declared Terry, her dark eyes glinting as she spoke from first hand experience, when I asked how her understanding of life had been altered by becoming homeless. “Why is it that the economic underclass are being hammered for the mess that we’re in?” she asked in furious indignation, “I think what’s opened my eyes is that there’s so much kindness and support coming from people who have got very little. I can’t deal with the big picture, I tend to narrow it down to the people in the room and just keep chipping away at small changes. And I’m going to do this for the rest of my life.” There was an unsentimental fire in Terry’s rhetoric, denoting someone who had been granted a hard won clarity of vision, and at the Code St hostel where I saw the performance I was touched to see her exchanging greetings with long-term homeless people she had known over the years she had worked with Cardboard Citizens.

As we left Dino’s Cafe and walked up the steps of Christ Church, Spitalfields, to take Terry’s portrait in the Winter sunlight, she cast her eyes around in wonder at the everyday spectacle of people walking to and fro, and confessed to me, “I teach up at Central School of Speech & Drama now and it’s quite amazing to think ten years ago I was sitting in a hostel, wondering what’s going to happen next and what’s my future going to be? Am I going to be like that woman down the hall, drunk off her head, or on crack?” Then she it shrugged off as she turned to the camera.

Terry thought often about her brother. “His eyesight started to go and he set fire to the bed,” she told me, explaining why it became imperative to move in with him, “He was a stubborn guy but he had to concede that he needed help. He was developing dementia and his eyesight was fading.” It was his unexpected illness and death that triggered the big changes in her existence, and afterwards Terry found herself at the centre of a whole new life.

Terry when she started with Cardboard Citizens in 2002.

“Terry worked for Cardboard Citizens after finding us first in the late nineties in the hostel in Mare St, an old police section house, where she was living and where we were first based. As she never tired of telling, she participated in a workshop I led in the old gym in the basement of the hostel, and was as mischievous on that first encounter as ever after, refusing to come down from one of those hanging ropes, and generally disrupting, in a most creative way. She was an actor for us for some years, then graduated to the role of Joker (facilitator/difficultator) and workshop leader, then Associate Director. She stepped down a couple of years back to care for her lifelong partner Kath Beach.”

Adrian Jackson, former Director of Cardboard Citizens

Charles Jones, Photographer & Gardener

Tickets are available for my tour throughout August & September

Garden scene with photographer’s cloth backdrop c.1900

These beautiful photographs are all that exist to speak of the life of Charles Jones. Very little is known of the events and tenor of his existence, and even the survival of these pictures was left to chance, but now they ensure him posthumous status as one of the great plant photographers. When he died in Lincolnshire in 1959, aged 92, without claiming his pension for many years and in a house without running water or electricity, almost no-one was aware that he was a photographer. And he would be completely forgotten now, if not for the fortuitous discovery made twenty-two years later at Bermondsey Market, of a box of hundreds of his golden-toned gelatin silver prints made from glass plate negatives.

Born in 1866 in Wolverhampton, Jones was an exceptionally gifted professional gardener who worked upon several private estates, most notably Ote Hall near Burgess Hill in Sussex, where his talent received the attention of The Gardener’s Chronicle of 20th September 1905.

“The present gardener, Charles Jones, has had a large share in the modelling of the gardens as they now appear, for on all sides can be seen evidence of his work in the making of flowerbeds and borders and in the planting of fruit trees. Mr Jones is quite an enthusiastic fruit grower and his delight in his well-trained trees was readily apparent…. The lack of extensive glasshouses is no deterrent to Mr Jones in producing supplies of choice fruit and flowers… By the help of wind screens, he has converted warm nooks into suitable places for the growing of tender subjects and with the aid of a few unheated frames produces a goodly supply. Thus is the resourcefulness of the ingenious gardener who has not an unlimited supply of the best appurtenances seen.”

The mystery is how Jones produced such a huge body of photography and developed his distinctive aesthetic in complete isolation. The quality of the prints and notation suggests that he regarded himself as a serious photographer although there is no evidence that he ever published or exhibited his work. A sole advert in Popular Gardening exists offering to photograph people’s gardens for half a crown, suggesting wider ambitions, yet whether anyone took him up on the offer we do not know. Jones’ grandchildren recall that, in old age, he used his own glass plates as cloches to protect his seedlings against frost – which may explain why no negatives have survived.

There is a spare quality and an uncluttered aesthetic in Jones’ images that permits them to appear contemporary a hundred years after they were taken, while the intense focus upon the minutiae of these specimens reveals both Jones’ close knowledge of his own produce and his pride as a gardener in recording his creations. Charles Jones’ sensibility, delighting in the bounty of nature and the beauty of plant forms, and fascinated with variance in growth, is one that any gardener or cook will appreciate.

Swede Green Top

Bean Runner

Stokesia Cyanea

Turnip Green Globe

Bean Longpod

Potato Midlothian Early

Pea Rival

Onion Brown Globe

Cucumber Ridge

Mangold Yellow Globe

Bean (Dwarf) Ne Plus Ultra

Mangold Red Tankard

Seedpods on the head of a Standard Rose

Ornamental Gourd

Bean Runner

Apple Gateshead Codlin

Captain Hayward

Larry’s Perfection

Pear Beurré Diel

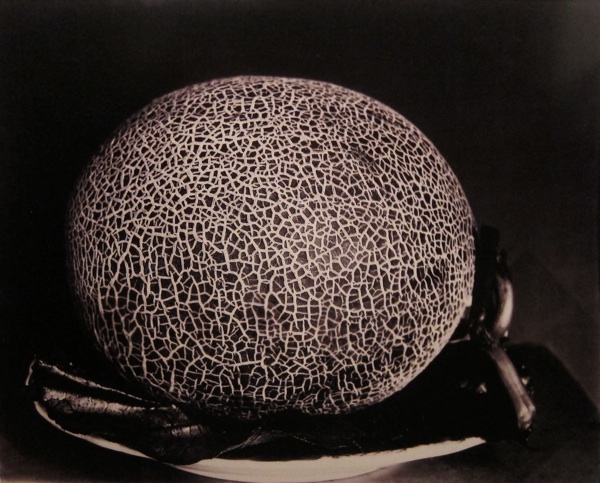

Melon Sutton’s Superlative

Mangold Green Top

Charles Harry Jones (1866-1959) c. 1904

The Plant Kingdoms of Charles Jones by Sean Sexton & Robert Flynn Johnson is published by Thames & Hudson

You might also like to read about

The Secret Gardens of Spitalfields

Thomas Fairchild, Gardener of Hoxton

Buying Vegetables for Leila’s Shop