Ashley Jordan Gordon’s Street Styles

You might think that it is in the nature of photography to reveal the present moment. It should be easy to take a picture and say, “This is how we look now,” yet one of the most elusive subjects to reveal in photography is the distinct reality of the present day.

Mostly, the qualities that define the time we are living through are invisible to us because we lack the sense of perspective which only appears later, when we look back up0n the pictures in a few years time and – discovering the photographs in a drawer – we experience with the familiar shock of recognition, as what was once contemporary is shown to be of its period.

The challenge for any photographer is to recognise subjects that characterise the present moment and capture them in pictures, making tangible the world as it is today. This is a task of particular fascination for Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer Ashley Jordan Gordon, especially when it comes to photographing people in the street and recording their clothing. A native of San Francisco, and one who loves to travel, Ashley has the advantage of being able to observe what is distinctive about how people dress in London by contrast with other cities and countries.

Returning after a time away, Ashley set out to photograph the here and now of street styles. “I was looking to pick out patterns that seemed very ‘London’ to me,” Ashley revealed, “I wanted to discover what made you look at a person and see that they are truly part of the living organism of the London streets – an aesthetic emblem – each with their unique interpretations, but who have all grown to feed off the history of the city and had it bleed into their sartorial choices, so that when you look at them you don’t just think ‘London fashion’ you think ‘London.'”

Scrutinised with an anthropologist’s eye, two trends are emergent in these pictures recording a particularly stylish and occasionally narcissistic tribe of East Enders. The first is of young women appropriating the leather biker jacket as an assertion of masculine power and protective armour against the rigors of urban life. The second is the influence of the clothing of Londoners of years gone, apparent either in the wearing of old clothes, like the girl (pictured above) in granny’s tweed cost in Bishopsgate, or through reference to styles of earlier times such as the literary chap outside Leila’s Cafe with the elaborately tied neckerchief of a nineteenth century student.

The special quality of Ashley Jordan Gordon’s pictures is that they transcend the commonplaces of street style photography to become portraits of individuals, revealing the personalities of which their clothes are an integral expression. As one who spends a lot of time looking at old photographs, it is a strange experience looking at Ashley’s work because the clarity of her vision makes me I feel I am looking through the lens of time, yet being shown a world that still exists outside my own front door in Spitalfields.

In Brick Lane.

At London Fields.

Beside the Regent’s Canal.

At Leila’s Cafe, Calvert Avenue.

In the City of London.

Beside the Regent’s Canal.

At Broadway Market.

At Broadway Market.

By Haggerston Park.

By London Fields.

At Cowling & Wilcox, Shoreditch High St.

In Dray Walk, Truman Brewery.

Photographs © Ashley Jordan Gordon

You may also like to look at

Maurice Evans at Compton Verney

At the end of last Winter, when the snowdrops were out, I went down to Steyning in Sussex to meet Maurice Evans who, at eighty-three years old, has amassed the most comprehensive collection of fireworks in Britain. Upon my departure, we shook hands in the cellar beneath Maurice’s house where he keeps his precious secret hoard and I did not know if we should meet again. Yet such was my delight in the encounter that – now the leaves are falling and as we begin another Winter – I travelled up to Warwickshire this week to attend the opening of the exhibition of Maurice’s fireworks organised by the Museum of British Folklore.

Gravel crunched beneath the wheels of the car as it swept along the curved drive approaching Compton Verney, travelling through grounds laid out by Capability Brown – where an ornamental lake glinted in the last rays of the sun and giant cedars loomed from the shadows – delivering me to the portico of the great mansion in the dark. I hurried through stately rooms, hung with fine old paintings in golden frames, to enter a magnificent hall designed by Robert Adam, where champagne was being served to a crowd of local worthies in all manner of gold chains, and flaunting badges of office.

At the centre of the gathering, I found Maurice Evans, dapper in a mid-grey lounge suit, clinking glasses with Simon Costin who masterminded the show, dressed up like a dandy coster. Although attended by his wife Kit and their grown up children – all amazed at the places fireworks can lead you – Maurice was as restless as a mischievous imp, demonstrating the liberated soul of one who has spent his life doing what he loves, which is collecting and setting off fireworks. So, once the speeches were out of the way, we set off along passages and up staircases to enter the midnight blue rooms where Maurice’s collection was displayed.

“It all started when I was a little boy, I had asthma and couldn’t go out to see the fireworks,” Maurice reminded me, as if simply to explain it away, before he walked into the exhibition that is the culmination of his lifetime of collecting.

Earlier this year, Maurice first showed me his box of exploding fruit that he has kept safe for decades in a niche in his cellar, crowded among hundreds of other dusty old fireworks that tell the history of pyrotechnics in this country – because, since the firework companies never held archives and their creations vanished into smoke each Bonfire Night, it was left to Maurice to become the self-appointed custodian of this beloved yet largely unacknowledged area of our culture.

Coming upon Maurice’s exploding fruit displayed in a glass museum case, we exchanged a glance of wonder. Then I followed the line of Maurice’s tender gaze to his treasures, nestling there in their original box. “Those are just like mine,” he said, placing a hand affectionately on the glass and looking back to me with a twinkle in his eye. “They are yours,” insisted Kit as she arrived, and Maurice gave me a complicit smile, turning and gazing in pleasure upon the huge firework posters on the walls. Slowly, we walked among the cases of fireworks, some designed like crates of gunpowder, others like roman candles and rockets, yet Maurice did not look too closely because the contents were familiar to him. “I’ve got a lot more than this at home,” he confided to me in a pantomime whisper, a little baffled as he cast his eyes around at the excited throng flocking into the gallery behind us.

Unable to resist looking at a case of indoor fireworks, I stepped away through the crowd and then my attention strayed from one item to another, until an attendant warned me it was time to go outside for the firework display. The blue rooms had emptied out when Kit asked me if I had seen Maurice, so we did another circuit of the exhibition together but he was not to be found. As we descended the stairs, Kit was concerned lest Maurice miss the display in his honour. “This is a very important day for him,” she assured me. Joining Maurice’s children, we all walked around the side of the mansion in the deep darkness to the wide lawn where, we were advised, we should enjoy the most advantageous view of the fireworks.

Maurice was already there, eagerly waiting on the grass at the front of the crowd, looking over his shoulder with a cheery smile to welcome us late-comers. Once, Kit and her children would have stood alone while Maurice ran around in the dark with the fuse, through the years he organised displays for a living. Now they stood together -after all this time, still enraptured by the fireworks that have never lost their magic.

Maurice & Kit at the firework display.

Maurice Evans, firework collector extraordinaire, and Simon Costin of the Museum of British Folklore.

[youtube GvsM5XRA138 nolink]

The Museum of British Folklore’s exhibition Remember, Remember featuring Maurice Evans’ firework collection runs at Compton Verney until 11th December.

You may also like to read my original profile of Maurice Evans, Firework Collector

Maurice Evans, Firework Collector

I am republishing my pen portrait of Maurice Evans today to celebrate the opening of the exhibition of his collection of fireworks entitled Remember, Remember presented by the Museum of British Folklore at Compton Verney.

Maurice Evans has been collecting fireworks since childhood and now at eighty-two years old he has the most comprehensive collection in the country – so you can imagine both my excitement and my trepidation upon stepping through the threshold of his house in Steyning. My concern about potential explosion was relieved when Maurice confirmed that he has removed the gunpowder from his fireworks, only to be reawakened when his wife Kit helpfully revealed that Catherine Wheels and Bangers were excepted because you cannot extract the gunpowder without ruining them.

This statement prompted Maurice to remember with visible pleasure that he still had a collection of World War II shells in the cellar and, of course, the reinforced steel shed in the garden full of live fireworks. “Let’s just say, if there’s a big bang in the neighbourhood, the police always come here first to see if it’s me,” admitted Maurice with a playful smirk. “Which it often isn’t,” added Kit, backing Maurice up with a complicit demonstration of knowing innocence.

“It all started with my father who was in munitions in the First World War,” explained Maurice proudly, “He had a big trunk with little drawers, and in those drawers I found diagrams explaining how to work with explosives and it intrigued me. Then came World War II and the South Downs were used as a training ground and, as boys, we went where we shouldn’t and there were loads of shells lying around, so we used to let them off.”

Maurice’s radiant smile revealed to me the unassailable joy of his teenage years, running around the downs at Shoreham playing with bombs. “We used to set off detonators outside each other’s houses to announce we’d arrived!” he bragged, waving his left hand to reveal the missing index finger, blown off when the explosive in a slow fuse unexpectedly fired upon lighting. “That’s the worst thing that happened,” Maurice declared with a grimace of alacrity, “We were worldly wise with explosives!”

Even before his teens, the love of pyrotechnics had taken grip upon Maurice’s psyche. It was a passion born of denial. “I used to suffer from bronchitis and asthma as a child, so when November 5th came round, I had to stay indoors.” he confided with a frown, “Every shop had a club and you put your pennies and ha’pennies in to save for fireworks and that’s what I did, but then my father let them off and I had to watch through the window.”

After the war, Maurice teamed up with a pyrotechnician from London and they travelled the country giving displays which Maurice devised, achieving delights that transcended his childhood hunger for explosions. “In my mind, I could envisage the sequence of fireworks and colours, and that was what I used to enjoy. You’ve got all the colours to start with, smoke, smoke colours, ground explosions, aerial explosions – it’s endless the amount of different things you can do. The art of it is knowing how to choose.” explained Maurice, his face illuminated by the images flickering in his mind. Adding, “I used to be quite big in fireworks at one time.” with calculated understatement.

Yet all this personal history was the mere pre-amble before Maurice led me through his house, immaculately clean, lined with patterned carpets and papers and witty curios of every description. Then in the kitchen, overlooking the garden where old trees stood among snowdrops, he opened an unexpected cupboard door to reveal a narrow red staircase going down. We descended to enter the burrow where Maurice has his rifle range, his collections, model aeroplanes, bombs and fireworks – all sharing the properties of flight and explosiveness. Once they were within reach, Maurice could not restrain his delight in picking up the shells and mortars of his childhood, explaining their explosive qualities and functions.

But my eyes were drawn by all the fireworks that lined the walls and glass cases, and the deep blues, lemon yellows and scarlets of their wrappers and casings. Such evocative colours and intricate designs which in their distinctive style of type and motif, draw upon the excitement and anticipation of magic we all share as children, feelings that compose into a lifelong love of fireworks. Rockets, Roman Candles, Catherine Wheels, Bangers, and Sparklers – amounting to thousands in boxes and crates, Maurice’s extraordinary collection is the history of fireworks in this country.

“I wouldn’t say its made my life, but its certainly livened it up,” confided Maurice, seeing my wonder at his overwhelming display. Because no-one (except Maurice) keeps fireworks, there is something extraordinary in seeing so many old ones and it sets your imagination racing to envisage the potential spectacle that these small cardboard parcels propose.

Maurice outgrew the bronchitis and asthma to have a beautiful life filled with fireworks, to visit firework factories around Britain, in China, Australia, New Zealand and all over Europe, and to scour Britain for collections of old fireworks, accumulating his priceless collection. Now like an old dragon in a cave, surrounded by gold, Maurice guards his cellar hoard protectively and is concerned about the future. “It needs to be seen,” he said, contemplating it all and speaking his thoughts out loud, “I would like to put this whole collection into a museum. I don’t want any money. I want everyone to see what happened from pre-war times up until the present day in the progression of fireworks.”

“My father used to bring me the used ones to keep,” confessed Maurice quietly with an affectionate gleam in his eye, as he revealed the emotional origin of his collection, now that we were alone together in the cellar. With touching selflessness, having derived so much joy from collecting his fireworks, Maurice wants to share them with everybody else.

Maurice with his exploding fruit.

Maurice with his barrel of gunpowder.

Maurice with his grenades.

Maurice with a couple of favourite rockets.

Firework photographs copyright © Simon Costin

The Museum of British Folklore’s exhibition Remember, Remember featuring Maurice Evans’ firework collection runs at Compton Verney until 11th December.

You also like to read about Simon Costin, Museum of British Folklore

Polly Hope, Jobbing Artist

Polly Hope does not go out too much. And why should she, when she has her own dreamlike world to inhabit at the heart of Spitalfields? Step off Brick Lane, go through the tall gate, across the courtyard, past the hen house, through the studio, up the stairs and into the brewery – you will find Polly attended by the huge dogs and small cats, and a menagerie of other creatures that share the complex of old buildings which have been her home for more than forty years.

Here, Polly has her sculpture workshop, her painting studio, her kiln, her print room, her library and her office. It goes on and on. At every turn, there are myriad examples of Polly’s lifetime of boundless creativity – statues, paintings, quilts, ceramics and more. And, possessing extravagant flowing blonde hair and the statuesque physique of a dancer, Polly is a goddess to behold. One who know who she is and what she thinks, and one who does not suffer fools gladly.

So, while I was on my mettle when I visited Polly’s extraordinary dominion, equally I was intoxicated to be in the presence of one so wholly her own woman, capable of articulating all manner of surprising truths, and always speaking with unmediated candour from her rich experience of life.

“I don’t know where it comes from. My father was a general in the British Army with generations of soldiers behind him. There were no artists on the family, and I have never found any great grandmother’s tapestry or grandfather’s watercolours.

I went to Chelsea and the Slade, and hated it. They wanted to teach you how to express yourself, but I wanted to learn how to make things. So I went to live in a tiny village in Greece because it was cheap, and I supported myself and my family by writing novels under a pseudonym. That was where I discovered textiles because they still make quilts there, and I was looking for a way to make large works of art which I could transport in my car. So I used the quiltmaker to help with the sewing. Today there’s various wall hangings of mine in different places around the world.

My second husband, Theo Crosby, and I liked East London, and Mark Girouard – who was a friend – showed us this place and we bought it for tuppence ha-penny in the early seventies. At that point, the professional classes hadn’t realised Spitalfields was five minutes walk from the City, but we cottoned onto it. This was one of the little breweries put up in the eighteen forties to get the rookeries off gin and onto beer, and make a few pounds into the bargain. Brick Lane was not the area of play it is now, it was a working place then with drycleaners, ironmongers, chemists, all the usual High St shops – and I could buy everything I needed for my textiles.

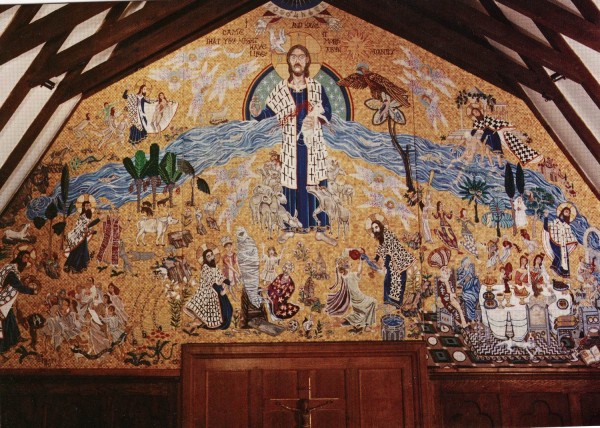

I decided it was time to do some community work, so I got everyone involved. Even those who couldn’t sew for toffee apples counted sequins for me. I did all the design and oversaw the work. The plan was to make a series of tableaux to hang down either side of Christ Church but we only completed the first two – the Creation of the World and the Garden of Eden – and they hang in the crypt now. I’ve done a lot for churches, I was asked to design a reredos for St Augustine’s at Scaynes Hill, but when I saw it – it was a perfect Arts & Crafts church – I said, “What you need is a Byzantine mosaic,” and they said, ‘”Yes.” And it took six years – we offered to include people’s pets in the design in return for five hundred pounds donation and that paid for the materials.

I am jack of all trades, tapestry, embroidery, painting, ceramics, stained glass windows, illustration, graphics, pots, candlesticks and bronzes. My ambition is to be a small town artist, so if you need decorations for the street party, or an inn sign painted, or a wedding dress designed, I could do it. I can understand techniques easily. When I worked with craftsmen in Sri Lanka, or with Ikat weavers, I learnt not to go into the workshop and ask them to make what you want, instead you get them to show you their techniques and you find a way to work with that. Techniques that have been refined over hundreds of years fascinate me. I don’t see any line between craft and art, I think it’s a mistake that crept in during the nineteenth century – high art and low craft.

I’m a countrywoman and I grew up on a mountain in Wales where there were always animals around. Living here, I play Marie Antoinette with my pets which all have opera names. My step-daughter Dido even brought her geese once to stay for Christmas. I have a mixed bag of chickens which give me four or five eggs a day – one’s not pulling her weight at the moment but I don’t know which it is. When they grow old, they retire to my niece in Kent. She takes my geriatric ones. I used to have more lurchers but one died and went to the big dog in the sky, now I have a new poodle I got six months ago and a yorkie who always takes a siesta with the au pair, as well as two cats. And I always had parrots, but the last one died. I got the original one, Figaro, from the Club Row animal market. One day I found him dead at the bottom of his cage. I just like living with animals, always have done all my life. A house is not a home without creatures in it.”

By now, we had emptied Polly’s teapot, so we set out on a tour of the premises, with a small procession of four legged creatures behind us. Polly showed me her merry-go-round horse from Jones Beach, and her hen house designed after the foundling Hospital in Florence, and her case of Staffordshire figures with some of her own slipped in among them, and the ceramic zodiac she made for Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, complementing the building designed by her husband Theo Crosby. And then we came upon the portraits of Polly’s military ancestors in bearskins and plaid trousers, in images dating back into the nineteenth century, and then we opened the cupboard of postcards of her work, and then we pulled box files of photographs off the shelf to rummage.

We lost track of time as it grew dark outside, and I thought – if I had created a world as absorbing as Polly Hope’s, I do not think I would ever go out either.

Monty & Fred, deer hound brothers, 2009.

Oscar, golden retriever.

Portrait of Theo Crosby, with one of the Club Row parrots and a lurcher.

Portrait of Roy Strong and his cat.

Portrait of Laura Williams depicted as Ariel.

Wall hanging at St Augustine’s, Scaynes Hill, West Sussex.

The Marriage at Canaa.

The Feeding of the Five Thousand.

The Red Flower, applique and quilting.

Archaeological Dig, applique and quilting.

Portrait of Polly Hope copyright © Lucinda Douglas Menzies

Artworks copyright © Polly Hope

Richard Jefferies in the City of London

Often when I set out for a walk from Spitalfields, my footsteps lead me to the crossroads outside the Bank of England , at the place where Richard Jefferies – a writer whose work has been an enduring inspiration – once stood. Like me, Jefferies also came to the city from the countryside and his response to London was one of awe and fascination. Whenever I feel lost in the metropolis, his writing is always a consolation, granting a liberating perspective upon the all-compassing turmoil of urban life and, in spite of the changes in the city, his observations resonate as powerfully today as they did when he wrote them. This excerpt from The Story of My Heart (1883), the autobiography of his inner life, describes the sight that met Richard Jefferies’ eyes when he stood upon that spot at the crossroads in the City of London.

“There is a place in front of the Royal Exchange where the wide pavement reaches out like a promontory. It is in the shape of a triangle with a rounded apex. A stream of traffic runs on either side, and other streets send their currents down into the open space before it. Like the spokes of a wheel converging streams of human life flow into this agitated pool. Horses and carriages, carts, vans, omnibuses, cabs, every kind of conveyance cross each other’s course in every possible direction.

Twisting in and out by the wheels and under the horses’ heads, working a devious way, men and women of all conditions wind a path over. They fill the interstices between the carriages and blacken the surface, till the vans almost float on human beings. Now the streams slacken, and now they rush again, but never cease, dark waves are always rolling down the incline opposite, waves swell out from the side rivers, all London converges into this focus. There is an indistinguishable noise, it is not clatter, hum, or roar, it is not resolvable, made up of a thousand thousand footsteps, from a thousand hoofs, a thousand wheels, of haste, and shuffle, and quick movements, and ponderous loads, no attention can resolve it into a fixed sound.

Blue carts and yellow omnibuses, varnished carriages and brown vans, green omnibuses and red cabs, pale loads of yellow straw, rusty-red iron clunking on pointless carts, high white wool-packs, grey horses, bay horses, black teams, sunlight sparkling on brass harness, gleaming from carriage panels, jingle, jingle, jingle! An intermixed and intertangled, ceaselessly changing jingle, too, of colour, flecks of colour champed, as it were, like bits in the horses’ teeth, frothed and strewn about, and a surface always of dark-dressed people winding like the curves on fast-flowing water. This is the vortex and whirlpool, the centre of human life today on the earth. Now the tide rises and now it sinks, but the flow of these rivers always continues. Here it seethes and whirls, not for an hour only, but for all present time, hour by hour, day by day, year by year.

All these men and women that pass through are driven on by the push of accumulated circumstances, they cannot stay, they must go, their necks are in the slave’s ring, they are beaten like seaweed against the solid walls of fact. In ancient times, Xerxes, the king of kings, looking down upon his myriads, wept to think that in a hundred years not one of them would be left. Where will be these millions of today in a hundred years? But, further than that, let us ask – Where then will be the sum and outcome of their labour? If they wither away like summer grass, will not at least a result be left which those of a hundred years hence may be the better for? No, not one jot! There will not be any sum or outcome or result of this ceaseless labour and movement, it vanishes in the moment that it is done, and in a hundred years nothing will be there, for nothing is there now. There will be no more sum or result than accumulates from the motion of a revolving cowl on a housetop.

I used to come and stand near the apex of the promontory of pavement which juts out towards the pool of life, I still go there to ponder. London convinced me of my own thought. That thought has always been with me, and always grows wider.”

Richard Jefferies (1848-1887)

Archive photographs copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

Glenys Bristow in Spitalfields

Glenys with her dad Stanley Arnabaldi in their cafe at 100 Commercial St

Glenys Bristow does not live in Spitalfields anymore. Today she lives in a well-kept flat in a quiet corner of Bethnal Green. Glenys might never even have come to Spitalfields if the Germans had not dropped a bomb on her father’s cafe in Mansell St, down below Aldgate. In fact, Glenys would have preferred to stay in Westcliff-on-Sea and never come to London at all, if she had been given the choice. Yet circumstances prevailed to bring Glenys to Spitalfields. And, as you can see from this picture taken in 1943 – in the cafe she ran with her father opposite the market – Glenys embraced her life in Spitalfields wholeheartedly.

“I came to London from Westcliff-on-Sea when I was fifteen. I didn’t like London at all. At first we were in Limehouse, I walked over to Salmon Lane and there was Oswald Mosley making a speech to his blackshirts. The police told us to go home. I was sixteen and I missed Westcliff so, me and my friend, we took a job in a cafe there for the Summer. We were naive. We weren’t streetwise. We didn’t have confidence like kids do today.

The family moved to Mansell St where had a cafe – our first cafe – and we lived above it. My father’s name was Arnabaldi, I used to hate it when I was at school. My father always wanted to have a cafe of his own. His father had come over from Italy and ran a shop in Friern Barnet but died when my father was only eleven, and my father told me his mother died young of a broken heart.

In September 1940, we were bombed out of Mansell St. Luckily no-one was inside at the time because it was the weekend. It was a big shock. My mother, sister Rita and brother Raymond had gone to Wales to visit my grandparents in the Rhonda Valley. I’d left that afternoon with my husband Jack, who was my boyfriend then. We had something to eat at his sister’s then we went by bus to my future in laws at Old St, where we slept in an Anderson shelter. On Monday morning, we were walking back to Mansell St and these people asked, “Where are you going?” I said, “Home, I’m going to change before going to work.” “You’ll be lucky,” they said. When we got there we found the site roped off. It was all gone. Just a pile of rubble.”

Glenys got married at eighteen years old at Arbour Sq Registry Office when Jack was enlisted. “We didn’t know if we were going to be here from one day to the next.” she told me, describing her experience of living through the blitz, suffering the destruction of her home in the bombing and then finding herself alone with a baby while her husband was at war.

“In late 1942, my father got the cafe at 100 Commercial St, Spitalfields, and I was living in a little house in Vallance Rd and had my first baby John and he was just eleven months old. My father bought the cafe and he arranged for me to stay in the top floor flat next door at 102, Commercial St. We just had two rooms above some offices with a cooker on the landing and a toilet. When the air raid sirens went, I didn’t want to get out of bed so my dad fixed up a bell on a string from next door. I used to wrap my baby in an eiderdown and wait until the shrapnel had stopped flying before I went out of the door into the street to the cafe next door.

I did a bit of everything, cooking, serving behind the counter. People came in from the Godfrey & Phillips cigarette factory, the market and all the workshops. The fruit & vegetable market kept going all through the war but, because of the blackout, it started later in the night. We were lucky being close to the market, we were never short of anything.

At the end of the war, Jack came back and worked for my parents until, after a few years, the lease on the cafe ran out and we had to give it up. In 1956, we rented a little cafe in Hanbury St that belonged to the Truman Brewery, but we were only there three years before we had to move again because they had expansion plans. We bought the cafe opposite where Bud Flanagan had been born and called it “Jack’s Cafe.” And we were there from 1960 until 1971.

Because of the market, we had to have dinner ready to serve at nine in the morning, and again from twelve ’til two. Nothing was frozen, everything was cooked daily and Jack used to buy everything fresh from the market. They said we had the best and the cleanest cafe in the Spitalfields Market, and a lot of our customers became friends. My daughter met her husband there, he was a porter – his whole family were porters – and my son went to work as a porter, he was called “an empty boy’ until he got his badge.

I just took it for granted. We used to open at half past four in the morning and I used to try and get cleaned up by half past six at night. It was very hard. Eventually, we sold it because I had back trouble and my husband bought a couple of lorries. In 1976, we moved from Commercial St to Chicksand St. I had four children altogether, only three that lived.

When it all changed, we went back – my daughter and I – to visit our old cafe. It had the same formica on the wall my husband had put up and I kept trying to look in the kitchen. I loved it when we worked for my mum and dad, and when we had our own place. I loved it and I miss it. They said I was the best pastry cook in Spitalfields.”

Glenys Bristow is a woman of astonishing resilience at ninety years old, with quick wits and a bright intelligence. Random events delivered her to Spitalfields in wartime, where she found herself at the centre of a lively working community. Losing everything when the bomb fell on her father’s cafe, and living day-to-day in peril of her life, she summoned extraordinary strength of character, bringing up her family and working long hours too. Glenys had no idea that she would live into another century, and enjoy the advantage of living peacefully in Bethnal Green and be able to look back on it all with affection.

Glenys Bristow

Glenys’ home in Mansell St after the bomb dropped in 1940.

At the cafe in Mansell St.

Glenys and her daughter Linda, 1950

Glenys and Linda visit the site of the former cafe in Mansell St, 1951.

Glenys with her children, John, Linda and Alan.

Glenys and her husband Jack with their first car.

Stan, Jack, Glenys and her mother Anne on a day trip to Broxbourne.

Glenys’ identity card with Commercial Rd mistakenly substituted for Commercial St.

Glenys with her granddaughter Sue Bristow.

You may also like to read about

At the Fish Harvest Festival

Frank David, Billingsgate Porter for sixty years

Thomas à Becket was the first rector of St Mary-at-Hill in the City of London, the ancient church upon a rise above the old Billingsgate Market, where each year at this season the Harvest Festival of the Sea is celebrated – to give thanks for the fish of the deep that we all delight to eat, and which have sustained a culture of porters and fishmongers here for centuries.

The market itself may have moved out to the Isle of Dogs in 1982, but that does not stop the senior porters and fishmongers making an annual pilgrimage back up the cobbled hill where, as young men, they once wheeled barrows of fish in the dawn. For one day a year, this glorious church designed by Sir Christopher Wren is recast as a fishmongers, with an artful display of gleaming fish and other exotic ocean creatures spilling out of the porch, causing the worn marble tombstones to glisten like slabs in a fish shop, and imparting an unmistakeably fishy aroma to the entire building. Yet it all serves to make the men from Billingsgate feel at home, in their chosen watery element – as Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer Ashley Jordan Gordon and I discovered when we went along to join the congregation.

Frank David and Billy Hallet, two senior porters in white overalls, both took off their hats – or “bobbins” as they are called – to greet us. These unique pieces of headgear once enabled the porters to balance stacks of fish boxes upon their heads, while the brim protected them from any spillage. Frank – a veteran of eighty-four years old – who was a porter for sixty years from the age of eighteen, showed me the bobbin he had worn throughout his career, originally worn by his grandfather Jim David in Billingsgate in the eighteen nineties and then passed down by his father Tim David.

Of sturdy wooden construction, covered with canvas and bitumen, stitched and studded, these curious glossy black artefacts seemed almost to have a life of their own. “When you had twelve boxes of kippers on your head, you knew you’d got it on,” quipped Billy, displaying his “brand new” hat, made only in the nineteen thirties. A mere stripling of sixty-eight, still fit and healthy, Billy continues to work at the new Billingsgate market driving a fork lift truck, having started his career at Christmas 1959 in the old Billingsgate market carrying boxes on his bobbin and wheeling barrows of fish up the incline past St Mary-at-Hill to the trucks waiting in Eastcheap. Caustic that the City of London is revoking the porters’ licences after more than one hundred and thirty years, nevertheless he is “hanging on” as long as he can. “Our traditions are disappearing,” he confided to me in the churchyard, rolling his eyes and striking a suitably elegiac Autumnal note.

Proudly attending the spectacular display of fish in the porch, I met Eddie Hill, a fishmonger who started his career in 1948. He recalled the good times after the war when fish was cheap and you could walk across Lowestoft harbour stepping from one herring boat to the next. “My father said, ‘We’re fishing the ocean dry and one day it’ll be a luxury item,'” he told me, lowering his voice, “And he was right, now it has come to pass.” Charlie Caisey, a fishmonger who once ran the fish shop opposite Harrods, employing thirty-five staff, showed me his daybook from 1967 when he was trading in the old Billingsgate market. “No-one would believe it now!” he exclaimed, wondering at the low prices evidenced by his own handwriting, “We had four people then who made living out of just selling parsley and two who made a living out of just washing fishboxes.”

By now, the swelling tones of the organ installed by William Hill in 1848 were summoning us all to sit beneath Wren’s cupola and the Billingsgate men, in their overalls, modestly occupied the back row as the dignitaries of the City, in their dark suits and fur trimmed robes, processed to take their seats at the front. We all sang and prayed together as the church became a great lantern illuminated by shifting patterns of October sunshine, while the bones of the long-dead slumbered peacefully beneath our feet. The verses referring to “those who go down the sea in ships and occupy themselves upon the great waters,” and the lyrics of “For those in peril on the sea” reminded us of the plain reality upon which the trade is based, as we sat in the elegantly proportioned classical space and the smell of fish drifted among us upon the currents of air.

In spite of sombre regrets at the loss of stocks in the ocean and unease over the changes in the industry, all were unified in wonder at miracle of the harvest of our oceans and by their love of fish – manifest in the delight we shared to see such an extravagant variety displayed upon the slab in the church. And I shall be enjoying my own personal Harvest Festival of the Sea in Spitalfields for the next week, thanks to the large bag of fresh fish that Eddie Hill slipped into my hand as I left the church.

St Mary-at-Hill was rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren in 1677.

Senior fishmongers from Billingsgate worked from dawn to prepare the display of fish in the church.

Fishmonger Charlie Caisey’s market book from 1967.

Charlie Caisey explains the varieties of fish to the curious.

Gary Hooper, President of the National Federation of Fishmongers, welcomes guests to the church.

Frank David and Billy Hallet, Billingsgate Porters

Frank’s “bobbin” is a hundred and twenty years old and Billy’s is “brand new” from the nineteen thirties.

Billy Hallet’s porter’s badge, soon to be revoked by the City of London.

Jim Shrubb, Beadle of Billingsgate with friends.

The mace of Billingsgate, made in 1669.

John White (President & Alderman), Michael Welbank (Master) and John Bowman (Secretary) of the Billingsgate Ward Club.

Crudgie, Sailor, Biker and Historian.

Dennis Ranstead, Sidesman Emeritus and Graham Mundy, Church Warden of St Mary-at-Hill.

Senior Porters and Fishmongers of Billingsgate.

Frank sweeps up the parsley at the end of the service.

The cobbled hill leading down from the church to the old Billingsgate Market.

Frank David with the “bobbin” first worn by his grandfather Jim David at Billingsgate in the 1890s.

Photographs copyright © Ashley Jordan Gordon

You may also like to read about

At the Pearly Kings & Queens’ Harvest Festival

Or see other photographs by Ashley Jordan Gordon