Scars Of War

Taking advantage of yesterday’s bright October sunshine, I set out for a walk across London with my camera to see what shrapnel and bomb damage I could find still visible from the last century. Much of the damage upon brick structures appears to have gone along with the walls, since most of what I discovered was upon stone buildings.

Shrapnel damage at the junction of Mansell St & Chambers St from World War II

Shrapnel pock-marks upon Southwark Cathedral from February 1941

Damage at St Bartholomew’s Hospital from zeppelin raids on 8th September 1915 and on 7th July 1917

Damage at St Bartholomew’s Hospital from zeppelin raids on 8th September 1915 and on 7th July 1917

Damage at Stone Buildings, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, from a bomb dropped on Wednesday 18th December 1917 at 8pm

Damage at Stone Buildings, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, from a bomb dropped on Wednesday 18th December 1917 at 8pm

Repair of shrapnel damage from September 194o at University College London, Zoology Museum, Gower St

Damage at St Clement Dane’s in the Strand from 10th May 1941 when the church was gutted

Damage at St Clement Dane’s in the Strand from 10th May 1941 when the church was gutted

Sphinx on the Embankment with damage from the first raid by German aeroplanes Tuesday 4th September 1917

Cleopatra’s Needle with damage from the first raid by German aeroplanes Tuesday 4th September 1917

Damage at Victoria & Albert Museum from two bombs in Exhibition Rd during World War II

Damage at Victoria & Albert Museum from two bombs in Exhibition Rd during World War II

Damage at Tate Britain from September 16th 1940

Please tell me of more locations of visible bomb damage and I will extend this series

You may also like to read about

The Baddeley Brothers Book

Over recent months, I have been collaborating with designer DAVID PEARSON to produce two books to delight you through the forthcoming winter months. Today, I invite you to join me in celebrating the publication of the first of these, BADDELEY BROTHERS at St Bride Printing Library, Fleet St, on October 15th at 7pm, with CRIES OF LONDON to follow in November.

Specialist printers & envelope makers, Baddeley Brothers have been established in the East End since the eighteen-twenties, yet before this they were clockmakers in the North of England since the sixteen-fifties, and it has been my great delight to write an account of the dramatic story spanning four centuries of how Baddeleys created one of today’s foremost printing companies. In six chapters, I trace the emergence of the modern culture of design and print from the journeyman clockmakers, die sinkers, letter cutters, engravers and artisans of the eighteenth century right up until the present day through the story of one family.

Specialist printers & envelope makers, Baddeley Brothers have been established in the East End since the eighteen-twenties, yet before this they were clockmakers in the North of England since the sixteen-fifties, and it has been my great delight to write an account of the dramatic story spanning four centuries of how Baddeleys created one of today’s foremost printing companies. In six chapters, I trace the emergence of the modern culture of design and print from the journeyman clockmakers, die sinkers, letter cutters, engravers and artisans of the eighteenth century right up until the present day through the story of one family.

David Pearson has worked with Baddeley Brothers to compose typographic samples exploiting their astonishing bravura printing techniques, engraving, embossing, foiling, debossing etc which will be tipped-in to all the copies of this beautiful book. Lucinda Rogers has done series of ink drawings of the printers and envelope makers at work at Baddeley Brothers factory in London Fields. Adam Dant has drawn a fold-out map which shows the locations of Baddeleys’ print works around the City of London and East End in the last two hundred years.

Please come along to ST BRIDE INSTITUTE, off Fleet St, on THURSDAY 15th OCTOBER at 7pm for drinks and book signing, as well as the opportunity to try working an embossing machine and make your own sample to take home.

NUMBERS ARE LIMITED SO PLEASE CLICK TO REGISTER FOR YOUR FREE TICKET

Jim Roche at the Heidelberg platen press

Gita Patel & Wendy Arundel and-folding & glueing envelopes

Gita Patel & Wendy Arundel and-folding & glueing envelopes

Gary Cline setting up the envelope machine

Jon Webster cutting a force

Working a manual die-stamping machine

Working a manual die-stamping machine

Paul King running a four-colour crest on the auto die-stamping press

Magnifying glass and tools

Jon Webster die-stamping a crest

Jon Webster die-stamping a crest

Danny Ede running the foiling machine

Typographic designs by David Pearson and drawings by Lucinda Rogers

You may also like to read about

Upon the Origins of Baddeley Brothers

JJ Baddeley, Die Sinker & Lord Mayor

Roland Collins, Photographer

Celebrating the achievements of artist Roland Collins who died on Sunday aged ninety-seven, it is my pleasure to show this selection of his evocative photographs of the East End and the City. For a spell in the sixties, while he was working as a Commercial Artist for the Scientific Publicity Agency in Fleet St, Roland Collins had access to a darkroom which enabled him to develop his own photography, and he produced striking and imaginative photoessays exploring different aspects of London life.

Fairground on the Hackney Marshes.

Salvation Army prayer meeting in the Lea Bridge Rd.

In Petticoat Lane.

In the East India Dock Rd.

Porters at Billingsgate.

Spirits are high as a porter is hoist onto his own shellfish barrow by his sixteen stone son.

A porter makes a bit extra on the side, street trading in boots and shoes.

The Monument.

View from the top of the Monument.

Looking down Eastcheap from the Monument.

Fish shop by the Monument.

Visitors at the top of the Monument.

The shadow of the Monument cast upon King William St.

Relief upon the Danish Embassy at Wellclose Sq at the time of demolition – now removed to Belgravia.

In Albury Rd, Rotherhithe.

At Limehouse Basin.

Photographs copyright © Estate of Roland Collins

You may also like to take a look at

Dennis Anthony’s Petticoat Lane

So Long, Roland Collins

Today I publish my interview with Roland Collins as a tribute to the late-blooming artist who drew Spitalfields and the East End in the fifties and died on Sunday at the fine old age of ninety-seven years

Roland Collins

Ninety-seven year old artist Roland Collins lived with his wife Connie in a converted sweetshop south of the river that he crammed with singular confections, both his own works and a lifetime’s collection of ill-considered trifles. Curious that I had come from Spitalfields to see him, Roland reached over to a cabinet and pulled out the relevant file of press cuttings, beginning with his clipping from the Telegraph entitled ‘The Romance of the Weavers,’ dated 1935.

“Some time in the forties, I had a job to design a lamp for a company at 37 Spital Sq” he revealed, as if he had just remembered something that happened last week,“They were clearing out the cellar and they said, ‘Would you like this big old table?’ so I took it to my studio in Percy St and had it there forty years, but I don’t think they ever produced my lamp. I followed that house for a while and I remember when it came up for sale at £70,000, but I didn’t have the money or I’d be living there now.”

As early as the thirties, Roland visited the East End in the footsteps of James McNeill Whistler, drawing the riverside, then, returning after the war, he followed the Hawksmoor churches to paint the scenes below. “I’ve always been interested in that area,” he admitted wistfully, “I remember one of my first excursions to see the French Synagogue in Fournier St.”

Of prodigious talent yet modest demeanour, Roland Collins was an artist who quietly followed his personal enthusiasms, especially in architecture and all aspects of London lore, creating a significant body of paintings while supporting himself as designer throughout his working life. “I was designing everything,” he assured me, searching his mind and seizing upon a random example, “I did record sleeves, I did the sleeve for Decca for the first Long-Playing record ever produced.”

From his painting accepted at the Royal Academy in 1937 at the age of nineteen, Roland’s pictures were distinguished by a bold use of colour and dramatic asymmetric compositions that revealed a strong sense of abstract design. Absorbing the diverse currents of British art in the mid-twentieth century, he refined his own distinctive style at his studio in Percy St – at the heart of the artistic and cultural milieu that defined Fitzrovia in the fifties. “I used to take my painting bag and stool, and go down to Bankside.” he recalled fondly, “It was a favourite place to paint, especially the Old Red Lion Brewery and the Shot Tower before it was pulled down for the Festival of Britain – they called it the ‘Shot Tower’ because they used to drop lead shot from the top into water at the bottom to harden them.”

Looking back over his nine decades, surrounded by the evidence of his achievements, Roland was not complacent about the long journey he had undertaken to reach his point of arrival – the glorious equilibrium of his life when I met him.

“I come from Kensal Rise and I was brought up through Maida Vale.” he told me, “On my father’s side, they were cheesemakers from Cambridgeshire and he came to London to work as a clerk for the Great Central Railway at Marylebone. Because I was good at Art at Kilburn Grammar School, I went to St Martin’s School of Art in the Charing Cross Rd studying life drawing, modelling, design and lettering. My father was always very supportive. Then I got a job in the studio at the London Press Exchange and I worked there for a number of years, until the war came along and spoiled everything.

I registered as a Conscientious Objector and was given light agricultural work, but I had a doubtful lung so nothing much materialised out of it. Back in London, I was doing a painting of the Nash terraces in Regent’s Park when a policeman came along and I was taken back to the station for questioning. I discovered that there were military people based in those terraces and they wanted to know why I was interested in it.

Eventually, my love of architecture led me to a studio at 29 Percy Studio where I painted for the next forty years, after work and at weekends. I freelanced for a while until I got a job at the Scientific Publicity Agency in Fleet St and that was the beginnings of my career in advertising, I obviously didn’t make much money and it was difficult work to like.”

Yet Roland never let go of his personal work and, once he retired, he devoted himself full-time to his painting, submitting regularly to group shows but reluctant to launch out into solo exhibitions – until reaching the age of ninety.

In the next two years, he enjoyed a sell-out show at a gallery in Sussex at Mascalls Gallery and an equally successful one in Cork St at Browse & Darby. Suddenly, after a lifetime of tenacious creativity, his long-awaited and well-deserved moment arrived, and I consider my self privileged to have witnessed the glorious apotheosis of Roland Collins.

Brushfield St, Spitalfields, 1951-60 (Courtesy of Museum of London)

Columbia Market, Columbia Rd (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St George in the East, Wapping, 1958 (Courtesy of Electric Egg)

Mechanical Path, Deptford (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

Fish Barrow, Canning Town (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St Michael Paternoster Royal, City of London (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St Anne’s, Limehouse (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St John, Wapping, 1938

St John, Wapping, 1938

Spark’s Yard, Limehouse

Images copyright © Roland Collins

At The Unveiling Of The Huguenot Plaque

Mavis Bullwinkle at Hanbury Hall

I hope Mavis Bullwinkle will not be too embarrassed if I reveal to you that, of all those who attended the unveiling of the Huguenot Plaque yesterday, it was she whose involvement with the Hanbury Hall extends the longest. Mavis’ uncle Albert was caretaker there before the war in the thirties and Mavis confessed to me that, as child, she remembers performing plays with her cousins on the stage after-hours, when she returned from being an evacuee at the end of the war. In 1951 at the age of nineteen, Mavis joined the weekly bible class there when her own church, All Saints Spitalfields, was demolished and then she graduated to the role of Sunday School teacher which occupied her each weekend until 1981.

Mavis may not herself be a Huguenot but, as a local resident for more than eighty years, she has come to embody a certain continuity in the neighbourhood and her generosity of spirit is emblematic of the best tradition of Spitalfields. As you can imagine, there was no shortage of Huguenot descendants yesterday to remember the quarter of a million refugees who came to Britain in the seventeenth century and, in particular, the twenty thousand who came to Spitalfields.

The Hanbury Hall was originally built as a Huguenot Chapel in 1719 then extended to the street and converted as a church hall for Christ Church in 1887 and now has been newly restored with flats on the top. Yesterday’s unveiling of the plaque was the culmination of three years of Huguenots of Spitalfields festivals organised by Charlie De Wet which were attended by more than twenty thousand people and the plaque of twenty Delft tiles designed by Paul Bommer is the legacy of this project.

As we all sat in the three hundred year old hall and listened to the story of the Huguenots, how they fled their home country in fear of their lives, of the refugee camps that were created here and of the charities that raised funds, the parallel to the contemporary crisis became inescapable. At the conclusion of the three year Huguenots of Spitafields festival which has brought light to the unexpected contributions of the Huguenots to British society, I think we all recognised that as one story ended another was just beginning.

Paul Bommer’s Huguenot Plaque

Charlie de Wet, Director of the Huguenot Festival for the last three years

Rev Andy Rider, Rector of Christ Church, leads the service of thanksgiving

You may also like to read about

At The Harvest Festival Of The Sea

Today I preview the Fish Harvest Festival which will take place this year on Sunday 11th October at 11am at St Mary-At-Hill, the Billingsgate Church, Lovat Lane, Eastcheap, EC3R 8EE

Frank David, Billingsgate Porter for sixty years

Thomas à Becket was the first rector of St Mary-at-Hill in the City of London, the ancient church upon a rise above the old Billingsgate Market, where each year at this season the Harvest Festival of the Sea is celebrated – to give thanks for the fish of the deep that we all delight to eat, and which have sustained a culture of porters and fishmongers here for centuries.

The market itself may have moved out to the Isle of Dogs in 1982, but that does not stop the senior porters and fishmongers making an annual pilgrimage back up the cobbled hill where, as young men, they once wheeled barrows of fish in the dawn. For one day a year, this glorious church designed by Sir Christopher Wren is recast as a fishmonger’s shop, with an artful display of gleaming fish and other exotic ocean creatures spilling out of the porch, causing the worn marble tombstones to glisten, and imparting an unmistakeably fishy aroma to the entire building. Yet it all serves to make the men from Billingsgate feel at home, in their chosen watery element.

Frank David and Billy Hallet, two senior porters in white overalls, both took off their hats – or “bobbins” as they are called – to greet me. These unique pieces of headgear once enabled the porters to balance stacks of fish boxes upon their heads, while the brim protected them from any spillage. Frank – a veteran of eighty-four years old – who was a porter for sixty years from the age of eighteen, showed me the bobbin he had worn throughout his career, originally worn by his grandfather Jim David in Billingsgate in the eighteen nineties and then passed down by his father Tim David.

Of sturdy wooden construction, covered with canvas and bitumen, stitched and studded, these curious glossy black artefacts seemed almost to have a life of their own. “When you had twelve boxes of kippers on your head, you knew you’d got it on,” quipped Billy, displaying his “brand new” hat, made only in the nineteen thirties. A mere stripling of sixty-eight, still fit and healthy, Billy started his career at Christmas 1959 in the old Billingsgate market carrying boxes on his bobbin and wheeling barrows of fish up the incline past St Mary-at-Hill to the trucks waiting in Eastcheap. Caustic that the City of London revoked the porters’ licences after more than one hundred and thirty years, “Our traditions are disappearing,” he confided to me in the churchyard, rolling his eyes and striking a suitably elegiac Autumnal note.

Proudly attending the spectacular display of fish in the porch, I met Eddie Hill, a fishmonger who started his career in 1948. He recalled the good times after the war when fish was cheap and you could walk across Lowestoft harbour stepping from one herring boat to the next. “My father said, ‘We’re fishing the ocean dry and one day it’ll be a luxury item,'” he told me, lowering his voice, “And he was right, now it has come to pass.” Charlie Caisey, a fishmonger who once ran the fish shop opposite Harrods, employing thirty-five staff, showed me his daybook from 1967 when he was trading in the old Billingsgate market. “No-one would believe it now!” he exclaimed, wondering at the low prices evidenced by his own handwriting, “We had four people then who made living out of just selling parsley and two who made a living out of just washing fishboxes.”

By now, the swelling tones of the organ installed by William Hill in 1848 were summoning us all to sit beneath Wren’s cupola and the Billingsgate men, in their overalls, modestly occupied the back row as the dignitaries of the City, in their dark suits and fur trimmed robes, processed to take their seats at the front. We all sang and prayed together as the church became a great lantern illuminated by shifting patterns of autumn sunshine, while the bones of the dead slumbered peacefully beneath our feet. The verses referring to “those who go down the sea in ships and occupy themselves upon the great waters,” and the lyrics of “For those in peril on the sea” reminded us of the plain reality upon which the trade is based, as we sat in the elegantly proportioned classical space and the smell of fish drifted among us upon the currents of air.

In spite of sombre regrets at the loss of stocks in the ocean and unease over the changes in the industry, all were unified in wonder at miracle of the harvest of our oceans and by their love of fish – manifest in the delight we shared to see such an extravagant variety displayed upon the slab in the church. And I enjoyed my own personal Harvest Festival of the Sea in Spitalfields for the next week, thanks to the large bag of fresh fish that Eddie Hill slipped into my hand as I left the church.

St Mary-at-Hill was rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren in 1677

Senior fishmongers from Billingsgate worked from dawn to prepare the display of fish in the church

Fishmonger Charlie Caisey’s market book from 1967

Charlie Caisey explains the varieties of fish to the curious

Gary Hooper, President of the National Federation of Fishmongers, welcomes guests to the church

Frank David and Billy Hallet, Billingsgate Porters

Frank’s “bobbin” is a hundred and twenty years old and Billy’s is “brand new” from the nineteen thirties

Billy Hallet’s porter’s badge, now revoked by the City of London

Jim Shrubb, Beadle of Billingsgate with friends

The mace of Billingsgate, made in 1669

John White (President & Alderman), Michael Welbank (Master) and John Bowman (Secretary) of the Billingsgate Ward Club

Crudgie, Sailor, Biker and Historian

Dennis Ranstead, Sidesman Emeritus and Graham Mundy, Church Warden of St Mary-at-Hill

Senior Porters and Fishmongers of Billingsgate

Frank sweeps up the parsley at the end of the service

The cobbled hill leading down from the church to the old Billingsgate Market

Frank David with the “bobbin” first worn by his grandfather Jim David at Billingsgate in the 1890s

Photographs copyright © Ashley Jordan Gordon

As part of the CRIES OF LONDON events at Bishopsgate Institute, we are staging a CHIT CHAT with traders from Billingsgate on November 4th at 7pm. Tickets are free. Click here to book yours.

You may also like to read about

The Last Fish Porters of Billingsgate Market

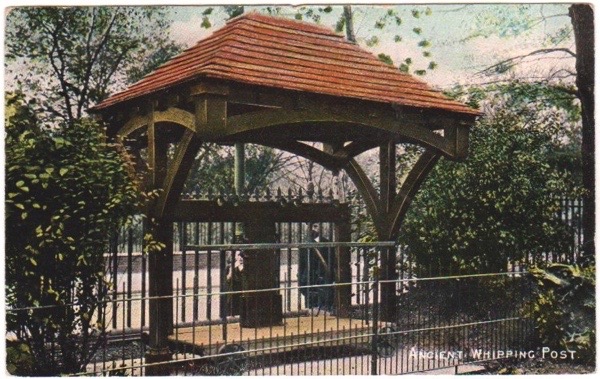

The Hackney Whipping Post

There is sometimes a certain tendency to talk about the past as if it were a better place, as if relics automatically speak of our ‘glorious history.’ Yet, occasionally, truth breaks through to remind us that, speaking of the past in this country, it was for many a place of suffering, of want and of violence – an inescapable but far less palatable historical reality.

Thus the emphasis of retelling history can often tend towards the celebratory and so, when the churchyard of St John-at-Hackney was handsomely restored with Lottery funds in recent years, the seventeenth century whipping post was conveniently consigned to the nearby backyard of Groundwork, the organisation which supervised the renovations, where it has been rotting ever since.

Historian Sean Gubbins of Walk Hackney drew my attention to this neglected artefact and took me there to see it last week. He showed me a photograph of it standing in the churchyard in 1919 and confirmed that it had decayed significantly in the last couple of years. Apparently, Hackney Council owns the whipping post but Sean can find no-one who wants to take responsibility for it and many would prefer if it simply rotted away.

In former centuries, the stocks, the whipping post and the pillory were essential elements of social control, but today these fearsome objects are treated with indifference or merely as subjects of ghoulish humour. Since they became defunct, they have acquired a phoney innocence as comic sideshows at school fetes where pupils can toss wet sponges at popular teachers to raise money for a worthy cause.

Yet the reality is that these instruments of violence and public humiliation were used to subjugate those at the margins of society – to punish the poor for petty thefts that might be as small as a loaf of bread, or to discourage vagrants, or to chasten prostitutes, or to drive homeless people out of the parish, or to subdue the mentally ill, or to penalise homosexuals, or to demean religious dissenters, or to intimidate immigrants into subservience, or against anyone at all who was considered socially unacceptable according to the prejudices of the day.

We need to remember this grim history, which reminds us that the struggle towards greater social equality and tolerance of difference in this country was a hard one, only achieved by those who resisted the culture of obedience enforced by state-sanctioned violence and enacted through instruments such as this whipping post.

Extract from Benjamin Clarke’s ‘Glimpses of Ancient Hackney & Stoke Newington’ 1894

Postcards supplied by Melvyn Brooks

Model of the Hackney whipping post

Tudor stocks and whipping post in the entrance to Shoreditch Church

If anyone is interested in helping to save and restore the whipping post please contact Sean Gubbins sean@walkhackney.co.uk

You might also like to read about