Doreen Fletcher, Painter

In the second of my series of profiles of artists featured in EAST END VERNACULAR, Artists who painted London’s East End streets in the 20th century to be published by Spitalfields Life Books in October, I present the remarkable paintings of Doreen Fletcher. Click here to learn how you can support the publication of EAST END VERNACULAR

Hairdresser, Ben Jonson Rd, 2001

This is a small selection of the paintings and drawings created by Doreen Fletcher in the East End between 1983 and 2003. “I was discouraged by the lack of interest,” admitted Doreen to me plainly, explaining why she gave up after twenty years of doing this work. Then, for a decade, all these pictures sat in Doreen’s attic until I persuaded her to take them out two years ago and let me photograph them for publication here on Spitalfields Life.

Doreen came to the East End in 1983 from West London. “My marriage broke up and I met someone new who lived in Clemence St, E14,” she revealed, “it was like another world in those days.” Yet Doreen immediately warmed to her new home and felt inspired to paint. “I loved the light, it seemed so sharp and clear in the East End, and it reminded me of the working class streets in the Midlands where I grew up,” she confided to me, “It disturbed me to see these shops and pubs closing and being boarded up, so I thought, ‘I must make a record of this,’ and it gave me a purpose.”

For twenty years, Doreen conscientiously sent off transparencies of her pictures to galleries, magazines and competitions, only to receive universal rejection. As a consequence, she forsook her art work entirely in 2003 and took a managerial job, and did no painting for the next ten years. But eventually, Doreen had enough of this too and has recently rediscovered her exceptional neglected talent in painting.

Many of Doreen’s pictures exist as the only record of places that have long gone and it is highly gratifying that she is finally receiving the recognition she deserves, not just for outstanding quality of her painting but also for her brave perseverance in pursuing her clear-eyed vision of the East End in spite of the lack of any interest or support.

Bartlett Park, 1990

Terminus Restaurant, 1984

Bus Stop, Mile End, 1983

Terrace in Commercial Rd under snow, 2003

Shops in Commercial Rd, 2003

Snow in Mile End Park, 1986

Laundrette, Ben Jonson Rd, 2001

The Lino Shop, 2001

Caird & Rayner Building, Commercial Rd, 2001

Rene’s Cafe, 1986

SS Robin, 1996

Benji’s Mile End, 1992

Railway Bridge, 1990

St Matthias Church, 1990

The Albion Pub, 1992

Turner’s Rd, 1998

The Condemned House, 1983

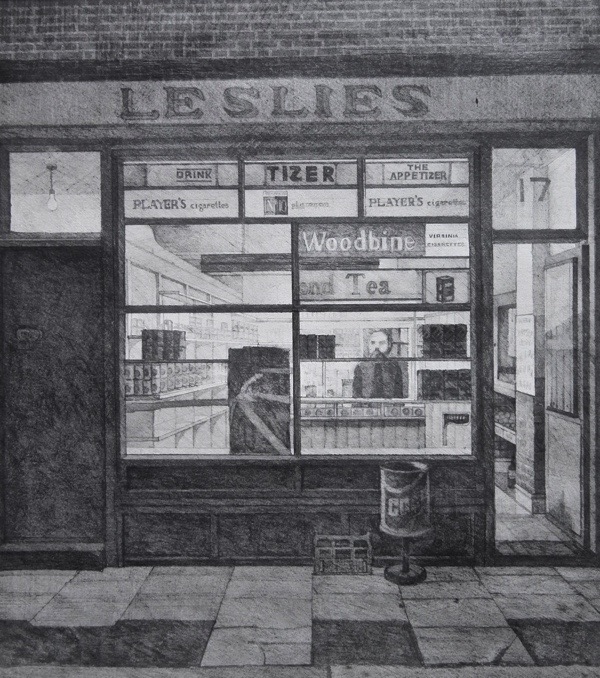

Leslie’s Grocer, Turner’s Rd, 1983 (Pencil Drawing)

Newsagents, Canning Town, 1991 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Bridge Wharf, 1984 (Pencil Drawing)

Pubali Cafe, Commercial Rd, 1990 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Ice Crean Van, 1990 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Images copyright © Doreen Fletcher

Click here to preorder a copy of EAST END VERNACULAR for £25

In the first of a series of profiles of artists featured in EAST END VERNACULAR, Artists who painted London’s East End streets in the 20th century to be published by Spitalfields Life Books in October, David Buckman author of From Bow to Biennale examines the life of Albert Turpin, artist, window cleaner & Mayor of Bethnal Green. Click here to learn how you can support the publication of EAST END VERNACULAR

Albert Turpin, Artist, Window Cleaner & Mayor of Bethnal Green

It is thanks to chance that the work of artist Albert Turpin has been preserved. Based in Claredale House, Claredale St, Bethnal Green, Turpin pursued his mission to record the area where he had been born and lived until his death in 1964. His work always sold well but, by the time his widow Sally died in 1981, Turpin’s realism had become unfashionable.

With their only daughter Joan living abroad, Sally worried about what to do with the legacy of paintings remaining after Turpin’s death. They might easily have ended in a skip but, luckily, storage was secured and they survived. Chance also played an important part in steering Turpin towards the East London Group and John Cooper, the man who inspired it.

Turpin’s background was not an auspicious one for an aspiring artist, born in 1900 in Ravenscroft Buildings off Columbia Rd, Bethnal Green, an area of acute deprivation. His father earned what little he could at jobs including being a tea-cooper, feather sorter and casual docker. When Albert Turpin left Globe Rd School at fourteen, like his father, he tried a bit of everything to earn a crust. But at fifteen, he joined the army until – at his father’s insistence – when the first World War was killing thousands, he was extracted and enlisted in the Royal Marines.

On ship, he began “to dabble away, trying to get Gibraltar and other overseas scenes down on canvas.” He was sufficiently encouraged by shipmates that, after he married Sally Fellows in 1922 and took up window cleaning, he finished the windows by lunchtime so he could spend the rest of the day painting. Interviewed after the Second World War when he was an established exhibitor at the Whitechapel Art Gallery’s East End Academy shows, Turpin revealed his motives as “a love of nature and a desire to copy it,” and the wish to show others “the beauty in the East End and to record the old streets before they go.”

Turpin was aware that tuition could improve his technique and he spent six years taking evening classes at Bethnal Green Working Men’s Institute and at the Bow & Bromley Commercial Institute, showing paintings in exhibitions held by the Institute at the Bethnal Green Museum. Among Albert’s teachers in Bethnal Green was the inspirational John Cooper, whose classes at Bow led to the important East London Art Club show at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in December 1928, in which Albert exhibited ten canvasses. They included characteristic and popular Turpin subjects, such as ‘The Dustbin,’ ‘At the Ale House,’ ‘Street Scene,’ ‘The Fruit Stall’ and ‘Jellied Eels’, but a portrait of ‘The Artist’s Wife’ was not for sale.

The Whitechapel show was so successful that Charles Aitken, Director of the National Gallery, Millbank, (now Tate Britain), transferred some of the pictures to his own gallery, including several of Turpin’s. Then, in the spring of 1929, a modified version of the Tate show toured to Salford, featuring Turpin’s ‘The Artist’s Wife’ and ‘The Dustbin,’ which had been bought by the influential dealer Sir Joseph Duveen.

While studying in Bethnal Green, Turpin met other future East London Group exhibitors who continued their tuition with John Cooper at Bow – men such as George Board, Archibald Hattemore, Elwin Hawthorne and the Steggles brothers, Harold and Walter. Hawthorne’s wife Lilian recalled Albert fondly as“a jolly chap” and Walter Steggles, who sketched with him, remembered his great sense of humour, describing Turpin as a man who “made jokes about everything including himself. He was liked by all who knew him.”

When Alex Reid & Lefevre launched the first of its eight annual exhibitions of work by the East London Group in November 1929, Turpin showed three pictures and in following years he contributed regularly to other East London Group exhibitions, as well as these annual shows at the Lefevre Galleries. But latterly his submissions became sporadic and his work was not present in the sixth exhibition in December 1934 or the last in December 1936. Group member Cecil Osborne told me that John Cooper had declined one of Turpin’s later pictures, a painting of his wife, and that the artist “went off in a huff and that was the last we saw of him.” Yet by the mid-thirties, Turpin had other demands upon his time.

In his fascinating unpublished autobiography, Turpin recalls how, once, on the way to an art group, he had been impressed to hear a speech by Bill Gee, a working class activist. It was during the winter of 1926, in the year of the General Strike, and Turpin wrote that Gee “did not teach me anything I did not already know, but what he did do was to make me forget all about my art class and join up with the organised workers right there.” Turpin joined the Labour Party, becoming affiliated to the North-East Bethnal Green Branch and eventually also to the Co-operative Party.

The East London Group had no political affiliations itself, but for Albert Turpin his political standpoint and his art merged naturally. His cartoons in local newspapers always “had a message,” Walter Steggles recalled. Speaking of Turpin’s painting ‘The Dustbin,’ originally displayed at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, Steggles recalled Turpin’s original title was ‘Man Must Eat,’ and the canvas depicted a man eating food scavenged from a bin – until Turpin modified the picture to avoid offending the public. Yet Turpin’s forthright titles did not deter the critics. Writing about the picture he submitted to the second Lefevre exhibition in December 1930, that model of refinement, The Lady, compared Turpin’s subjects to those of Daumier and Hogarth, praising his “rare and precious gift! – a sense of the physical beauty of oil paint.” Later Lefevre contributions would include titles that speak for themselves, such as ‘Unemployed,’ ‘Night Shelter,’ ‘Rags’ and ‘Slum Clearance.’

It was a tribute to Turpin’s physical stamina and determination that while earning his living as a window cleaner, he managed to pursue his political career and his art. He was an active anti-Fascist protester and, while a member of the Bethnal Green Borough Council, appeared at Old St Police Court accused of using insulting words and behaviour and assaulting a constable. He was also active in the Ex-Servicemen’s National Movement “for Peace, Freedom and Democracy” and supported the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

The Second World War offered further outlets for Turpin’s artistic talents. Having served part-time with the London Fire Brigade from early 1938, then full-time in September 1939 when he acted as secretary of a branch of the Fire Brigades Union, Turpin joined the National Fire Service in August 1941, remaining with it until October 1946. From 1940, he was an official Fire Brigade War Artist with his work exhibited both in Britain and North America. While an instructor at a London Fields Fire Service training school, after telling students the right way of doing a thing, he would sometimes “make a lightning sketch to show what might happen if they ignored my advice.”

After leaving the Fire Service, Turpin resumed window cleaning and part-time painting and was unanimously elected Mayor of Bethnal Green, 1946-47. He refused to wear mayoral robes, the Evening News reported, “because he thinks it is a waste of taxpayers’ money.” As a man with a strong moral standpoint, loathing gambling and – his mother having died of cirrhosis of the liver – refusing to clean pub windows, Turpin found Dr Frank Buchman’s Moral Re-Armament (MRA) movement attractive when he encountered it in 1946. Buchman hoped for “moral and spiritual rearmament” to achieve “a hate-free, fear-free, greed-free world.” After seeing the MRA play ‘The Forgotten Factor,’ Turpin was gripped by their message and became active in the cause. Early in 1947, MRA’s publication ‘New World News’ pictured Turpin on its cover as “Victory Mayor,” standing among blitzed ruins.

Until his death, seventeen years later, he continued to make drawings and paintings of Bethnal Green, Stepney, Hackney, Hoxton and Islington. Although the East London Group was no longer active post-war, Turpin still showed his pictures – at Morpeth School in Bethnal Green, Whitechapel Art Gallery, Guildhall Art Gallery and Qantas Gallery in Piccadilly.

Albert Turpin’s paintings are a unique record of the old East End by one who knew it intimately.

Columbia Market – Oil on board

The Arches, Mare St – Oil on board

Cable St – Oil on board

Marian Sq, Hackney – Oil on canvas, 1952

Rebuilding St Matthew’s Church, Bethnal Green – Oil on canvas, c.1956

Verger’s House, Shoreditch – Oil on canvas, 1954

Salmon & Ball, Bethnal Green – Oil on canvas, c.1955

Shakey’s Yard in Winter – Oil on Canvas, c.1952

Hackney Empire – Oil on board

East End Vernacular

Provisional cover design featuring ‘St James Rd, Old Ford’ by Henry Silk

With your help, this October I plan to publish EAST END VERNACULAR, a beautifully illustrated hardback book celebrating the work of artists who painted London’s East End streets in the 20th century.

In recent years, the East London Group of painters has been successfully reclaimed from obscurity – but I have found there are plenty of equally wonderful artists who came before and after who also deserve to be recognised, and a survey of all this important work is long overdue. Many of the paintings in the book have not been published before and many of these are by artists who have been unjustly neglected.

There are three ways you can help:

1. I am seeking readers who are willing to invest £1000 in EAST END VERNACULAR to help me bring recognition to this important aspect of East End culture, by cherishing these magnificent paintings in a handsome book. In return, we will publish your name in the book and invite you to a celebratory dinner hosted by yours truly at the end of June. If you would like to know more, please drop me an email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

2. Preorder a copy of EAST END VERNACULAR and you will receive your copy in the first week of October when the book is published. Click here to preorder your copy

3. If you own a painting of a street scene that you believe should be included in EAST END VERNACULAR please send me a photograph of it spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

On this page, you will find a selection of works from some of those artists we mean to include in EAST END VERNACULAR: John Allin, Pearl Binder, James Boswell, Roland Collins, Alfred Daniels, Anthony Eyton, Doreen Fletcher, Geoffrey Fletcher, Barnett Freedman, Noel Gibson, Charles Ginner, Harry Harmer, Elwin Hawthorne, Rose Henriques, Dan Jones, Nathaniel Kornbluth, Leon Kossoff, Cyril Mann, Jock McFadyen, Ronald Morgan, Grace Oscroft, Henry Silk, Harold Steggles, Walter Steggles & Albert Turpin.

The book will include a Prologue with paintings by nineteenth century artists and an Epilogue with works by artists painting the East End streets today including Nicholas Borden, Peta Bridle, Eleanor Crow, Adam Dant, Marc Gooderham, Joanna Moore & Lucinda Rogers.

I shall be opening the Write Idea Festival at the Idea Store in Whitechapel in November with an illustrated lecture on the artists in EAST END VERNACULAR and we are working with Hatchards to promote the book in the West End. There are forthcoming exhibitions this autumn of East London Group paintings at the Nunnery Gallery in Bow and at Southampton City Art Gallery where we will be doing EAST END END VERNACULAR events. Additionally, Townhouse in Spitalfields will be hosting a new Doreen Fletcher exhibition in October.

Consultants to the book include: Fiona Atkins, an expert on 20th century British Art and curator of Doreen Fletcher’s debut exhibition, David Buckman, author of From Bow to Biennale which rescued the East London Group from obscurity, Vicky Stewart, the genius researcher who discovered the Spitalfields Nippers and Alan Waltham who is the authority on the East London Group.

The book is designed by Friederike Huber, the distinguished book designer who has previously designed Brick Lane, East End, London Life, Spitalfields Nippers, Travellers Children in London Fields & Underground for Spitalfields Life Books.

Over the next week, I shall be publishing features about some of the artists from EAST END VERNACULAR

John Allin – Spitalfields Market, 1972

Pearl Binder – Aldgate, 1932 (Courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute)

James Boswell – Petticoat Lane (Courtesy of David Buckman)

Roland Collins – Brushfield St, Spitalfields, 1951-60 (Courtesy of Museum of London)

Alfred Daniels – Gramaphone Man on Wentworth St

Anthony Eyton , Christ Church Spitalfields, 1980

Doreen Fletcher – Turner’s Rd, 1998

Geoffrey Fletcher – D.Bliss, Alderney Rd 1979 (Courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives)

Barnett Freedman– Street Scene. 1933-39 (Courtesy of Tate Gallery)

Noel Gibson – Street Scene in Poplar (Courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives)

Charles Ginner – Bethnal Green Allotment, 1947 (Courtesy of Manchester City Art Gallery)

Elwin Hawthorne – Trinity Green Almshouses, 1935

Rose Henriques – Coronation Celebrations in Challis Court, 1937 (Courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives)

Dan Jones – Brick Lane, 1977

Leon Kossoff – Christ Church Spitalfields, 1999/2000 (Courtesy of Annely Juda Fine Art, London)

Cyril Mann – Christ Church seen over bombsites from Redchurch St, 1946 (Courtesy of Piano Nobile Gallery)

Jock McFadyen – Aldgate East

Grace Oscroft – Old Houses in Bow, 1934

Henry Silk – Snow, Rounton Rd, Bow

Harold Steggles – Old Ford Rd c.1932

Walter Steggles – Canal at Mile End

Albert Turpin, Columbia Market, Bethnal Green

Click here to preorder a copy of EAST END VERNACULAR for £25

Two Lost Breweries Of Whitechapel

Within living memory, Whitechapel was home to the Albion and the Blue Anchor Brewery, two of the largest breweries in the country, premises for Watney Mann and Charringtons respectively. Photographer Philip Cunningham‘s grandfather worked at The Albion brewery and it became his melancholy duty to record both breweries in the eighties at the point of their demise. (Accompanying text also by Philip Cunningham.)

The Albion Brewery in the nineteenth century

My grandfather was a train driver until the day he was discovered to be colour blind, when he was sacked on the spot. He then became a drayman and – apart from two world wars – spent the rest of his working life at the Albion Brewery in Whitechapel. He was one of the first draymen to drive a motorised vehicle, a skill which saved his life in WWI.

The brewery started trading in 1808 and although by 1819 it was under the control of Blake & Mann, by 1826 it was in the exclusive ownership of James Mann. In 1846, Crossman and Paulin became partners to form Mann, Crossman & Paulin Ltd. The brewery was re-built in 1863, becoming the most advanced brewery of that time, producing 250,000 barrels a year.

Stables were built on the east side of Cambridge Heath Rd with a nosebag room containing in excess of one hundred and fifty nosebags, each filled by a metal tube from the store above. The former Whitechapel workhouse in Whitechapel Rd was used for the bottling plant, but when this proved to be too small it was moved to a site on Raven Row, two hundred yards south.

In 1958, the company merged with Watney Combe & Reid to become Watney Mann Ltd. In 1978, a spokesperson for Grand Metropolitan the corporate owner who acquired Watney declared, ‘The bottling plant has a very strong future as a distribution and bottling centre for the GLC area and parts of Southern England.’ Yet the plant was closed in 1980 with a loss of two hundred jobs after the building was declared unsafe and too costly to repair. Keg filling transferred to Mortlake, the bottling plant became a distribution centre and the brewery was shut down in 1979. The buildings on the Whitechapel Rd were converted to flats and the rest of the site is now occupied by Sainsbury’s.

Gates of the Blue Anchor Brewery

In 1757, John Charrington moved his brewing business from Bethnal Green to the Mile End Rd. This was the Blue Anchor Brewery, and John Charrington’s brother Harry lived next to the brewery in Malplaquet House from about 1790 until his death in 1833.

The brewery was built on Charrington Park, extending for sixteen acres behind the malt stores. Some land was sold off for building and a section was given to St. Peter’s Church, while the remainder was used for cooperages and for stables housing one hundred horses and a blacksmith’s forge. There were also coppersmiths, tinsmiths, gasfitters, millwrights, hoopers, engineers, and carpenters with a timber store and saw pit. The hop store was a spacious darkened chamber one hundred feet long, filled from floor to ceiling with hops, and the odour was overpowering.

The Blue Anchor brewery became the second largest in London producing 20,252 barrels of beer a year. In the nineteenth century, steam engines were installed which ran until 1927, when they were replaced by electric power. During the Second World War, half the lorry fleet was commandeered for the army.

Yet in 1967, the company merged with Bass to become Charrington Bass and later Bass Ltd – the largest brewing company in the country. The last brew at Charringtons was in 1975 and distribution was then moved to Canning Town. A new administration block was built at a cost of three and a half million, only to be demolished for a retail park.

Photographs copyright © Philip Cunningham

You may also like to take a look at

Philip Cunningham’s London Docks

Philip Cunningham’s East End Portraits

More of Philip Cunningham’s Portraits

Yet More Philip Cunningham Portraits

Philip Cunningham at Mile End Place

So Long, Naseem Khan OBE

Today we pay tribute to Naseem Khan OBE who died yesterday at the age of seventy-eight. Naseem will be long remembered in the East End for her stirling work as Chair of the Friends of Arnold Circus, masterminding the restoration of the park and bandstand on the Boundary Estate in Shoreditch.

Behind this lyrical, quintessentially English image of a little girl surrounded by carnations in a cottage garden in Worcestershire lies an unexpected story – because this is a photogaph of Naseem Khan whose father was Indian and mother was German. They met in London and married in 1935, and Naseem was born in 1939. When the war came they could not return either to India, which was in the early throes of partition, or Germany which was under the control of Adolf Hitler, so they went to live in rural Worcestershire for the duration where Naseem’s mother was able to maintain a discreet profile, concealing her true nationality and passing as French.

These were the uneasy circumstances of Naseem’s origin yet they granted her a unique vision of society which informed her life’s work in all kinds of creative ways – including becoming Head of Diversity at the Arts Council and subsequently Chair of the Friends of Arnold Circus, the group responsible for the rescue and sympathetic renovation of the neglected park and bandstand at the centre of the Boundary Estate.

Naseem’s father, Abdul Wasi Khan was a doctor from Seoni, the eldest of ten in a struggling family who won an award from a foundation in Hyderabad to study in London where he completed a further three degrees, qualifying as the highest level of surgeon. Yet, as an Indian, discrimination prevented him practicing his expertise in this country at that time. Naseem’s mother, Gerda Kilbinger came to study English at a college in London and her best friend at the language school was dating an Indian doctor who was reportedly “so handsome, so smart.” However, when Gerda finally met this paragon who was to be her future husband she exclaimed “Ach, is that what the fuss is all about?” Gerda may have been initially unimpressed by Wasi’s diminutive stature, which matched her own, yet it was only the first of his qualities that she noticed, drawing them together them as a from couple from the margins in British society.

“They were very concerned that I and my brother be accepted, and they thought the best way to achieve that was to send us to boarding school. But at Roedean, where Home Counties girls were sent – destined to be secretaries at the Foreign Office before they found a suitable young man to marry – I was like a fish out of water,” admitted Naseem, speaking softly with sublime confidence yet without any shred of resentment, “My best friends were a small group of Jewish girls.”

“At the end of the war, my mother got permission to go and find her parents in Germany and it was very shocking, the damage, despair and the demoralisation. I was particularly impressed by my grandfather, a man of great integrity, and I would take my own children each year for open house on his birthday. He used to make a great soup, and members of the local football team and the mayor’s office would come. He would garden all summer long in his allotment and do metalwork in the winter. He had just a few good books and a few pieces of good furniture and I always liked that feeling, of having nothing superfluous.”

Blessed with a modest temperament and sharp intelligence, Naseem graduated from Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford and pursued a wide-ranging career as a journalist. She was among those who launched Notting Hill’s black newspaper The Hustler before becoming theatre editor at Time Out when the new experimental theatre erupted in Britain. Invited by the Arts Council to research aspects of immigrant culture, she left her job to write a report entitled The Arts Britain Ignores, a re-examination of what was considered as legitimate English culture which became a cornerstone of policy and led to a further career for Naseem at the Arts Council. “It was an important period of recognition of difference, striving to find a world in which all sides are possible, contained and honoured,” admitted Naseem in quiet reflection.

For twenty-five years, Naseem lived in Hampstead but when her children George and Amelia finished university, she found that her marriage had evaporated. Separating on amicable terms with her husband and splitting the proceeds of the family house, she began a new life in the East End sixteen years ago. “What I’d missed in Hampstead was diversity, a sense of community and dynamism,” she revealed to me with a weary smile one day, “And being closer to the Buddhist centre in the Roman Rd was a plus for me. When I first came to look at this terraced house beside Columbia Rd, it was summer and the little garden was an oasis and I thought, ‘This is where I could put down my new life.’ – I knew this was where I wanted to be, although I didn’t realise it at the time. I wanted to be in a place of change.”

Over five years as Chair of the Friends of Arnold Circus, Naseem created a charity with over five hundred members dedicated to bringing together the diverse community of the Boundary Estate. While the renovation of the park became the most visible aspect of the Friends’ work, all kinds of other projects including gardening and music-making still continue throughout the year. “I think my particular skill is being able to create a space in which people with different skills and different outlooks can work together and achieve what they want to,” revealed Naseem, demonstrating her innate magnanimity while thinking out loud. “I am a connector and it means recognising the synergy by which different people can come together to create something new.”

Naseem’s work contributed to a new sense of self respect and pride in the neighbourhood for the residents of the Boundary Estate. In this sense, Naseem Khan’s work in the East End was both a culmination of her personal journey, informed by her parents’ experiences, while also re-igniting the ethos of Sir Arthur Arnold who built the Estate.

She will be remembered as a notable figure in the authentic and radical tradition of social campaigners who have brought about real change for the people of the East End. Yet Naseem’s estimate of her achievement was simpler. “When you live a long time, you do a lot of things.” she assured me with a grin of self-effacing levity.

Naseem’s grandmother Maria Kilbinger with Naseem’s mother Gerda and Aunt Elsa in 1916

Naseem’s mother’s German school attendance card issued 1913

Gerda & Wasi, newly married in 1935 in Edinburgh

Naseem’s British identity card issued 1940

Naseem with her father, aged eight, 1948

Naseem’s family and neighbours in Worcestershire in 1951. Her mother Gerda stands in the centre with her father Wasi on the far right and her Uncle Mujtaba standing between them. Sitting in the centre is Naseem’s half-sister Shamim. Standing on the far left is Harold Tolly, the baker, with his wife Myfanwy, the midwife, seated on the right holding Anwar on her lap.

Naseem and her brother Anwar, 1952

Naseem at Oxford, Lady Margaret Hall, 1958

The Temptation of Buddha, Naseem is the dancer in front on the right

At a Buddhist retreat at the Upaya Zen Centre in New Mexico, 2007

Naseem Khan OBE (1939-2017)

Arnold Circus

You may also like to read

At Cable St Gardens

Cable St Community Gardens will open on Sunday 18th June from 10:30am – 4pm as part of London Open Garden Squares Weekend. Click here for more information.

In September 2003, photographer Chris Kelly was invited to the open day and the result was a year-long project which culminated in an exhibition and a book. Fifty-two plot holders took part, aged from seven to eighty and originating from a dozen different countries, yet all unified by a love of gardening and the need for a haven where they could cultivate flowers, grow vegetables, chat to neighbours or enjoy solitude. “Some of the old faces are no longer there,” Chris told me,“but the gardens thrive, new people have joined and it is still a magical place.”

Bill Wren – I was born in Wapping and I moved to Shadwell nine years ago. I’ve had the plot for about fifteen years. We never had a garden when I was young. The nearest I came to gardening was picking hops in Kent. Later I had a friend in Burgess Hill and I used to grow things in her garden. That’s where the greenhouse came from, I put it on the roof of the car and brought it up from Sussex. I’ve built a shed here and a pond. There are plenty of frogs and newts, and I’ve planted a bank next to the road. It’s a wildlife haven now.

Jane Sill – I was born in Liverpool. My grandfather had an allotment in County Durham and my father was a very good gardener. I helped with weeding and cultivated sunflowers. I was living in Cable Street in the late seventies in a top floor flat with no balcony. One day I went to a community festival and Friends of the Earth were offering plots here. I was given one in 1980 and I knew straight away how important it was to establish ourselves as an organisation. We’ve had a two year waiting list since 1981. At one time I was working in a Job Centre and people used to come in and put their names down for a plot.

Mohammed Rahmat Ali Pathni – I have always been a gardener. I started on my father’s land in Bangladesh and when I came to live in Birmingham in 1978 I had a garden behind the back yard. I have lived in Wapping since 1983 and started gardening in Cable Street ten years ago. I’m enjoying myself and it helps my frozen shoulder. I taught my children to garden and my wife often works here too. Many gardeners provide food for other people and I regularly give vegetables to friends. I also write poetry which is printed in the Eurobangla News Weekly, and I am a member of a writers’ group.

Alison Cochran – I moved to Shadwell five years ago because of the allotments and I live just across the road. I noticed them when I was living in Bethnal Green. I was born in Salisbury on a hill fort. I was keen on gardening when I was a child but when I came here I hadn’t gardened for years. I knew I wanted lots of flowers, but now I also grow salad vegetables and leeks, tomatoes, carrots and radishes. The soil is wonderful, everything seems to thrive here. I’ve used Victorian bricks for the paths because I wanted my plot to be in keeping with nearby housing.

Monir Uddin – I’ve lived in the borough for twenty years and I’ve gardened here for eight or nine years. The plot was completely wild at first. I had to uproot everything and it took about two years to get the soil right. I used to grow about sixty different plants and vegetables, including huge pumpkins. I love experimenting with plants and growing them for their medicinal properties. I’m a photographer and I also wanted to produce plants to photograph. I’ve done many different types of work including weddings and portraits. I was involved in the Bollywood film industry, I’ve photographed celebrities and at one time I had a restaurant.

Agatha Athanaze – I’ve been gardening here for twelve years. I was born in Dominica and came to Tower Hamlets in 1961. I’ve done different jobs. I’ve been a machinist and a cleaner. I live in Wapping now. I had a garden in Dominica so I did have some experience. The vegetables came first – I grow cabbages, onions, spring onions, runner beans, carrots, tomatoes, rhubarb and kidney beans. I like flowers too. I’ve ordered roses from Holland and from Spalding. I just like to come here and grow things. There are two benches but I haven’t time to sit down.

John Kelly – I was born in Cork City and I wasn’t a gardener. I came to this country in 1943 to work in the construction industry and started gardening as a hobby and to feed the family. I’ve had the plot here for seventeen years. I didn’t know much but I picked it up as I went along. I’ve always grown vegetables, never flowers. I can’t spend too much time here because I have to look after my wife and I have health problems too. I hate the sight of weeds but I don’t throw them out. I leave them on the ground to let them rot and they form green manure.

Manda Helal – I’m from Hertfordshire and I’ve lived in Tower Hamlets for twenty-six years. I’ve always been keen on gardening. We had a big garden when I was a child and I was given a section of my own. I’ve had my plot here for three years. My flat in Whitechapel is small and dark, so it’s wonderful to come here. The wheels are a frame for pumpkins. Squashes and pumpkins are so versatile. I grow artichokes and rocket, garlic, kale, cabbage, cauliflower, spinach and climbing purple beans. I’ve taught pottery in the borough for years and more recently I became a compost educator for the Women’s Environmental Network.

John Stokes – I’ve been gardening at Cable Street since I retired six years ago. I asked one of the nuns in the convent across the road and she said the allotments were for local people. I had no experience but I was brought up on a farm and I found I had an instinct for gardening. I came over from Ireland fifty years ago. I worked for London Transport for thirty-six years and missed only nine days. Now I’m at the gardens almost every day in summer and twice a week in winter. I grow vegetables for myself and my cousin and an aunt.

Anna Gaudion – I was born in Guernsey. I’ve lived in Stepney for the last ten years and I work as a midwife in Peckham. I was brought up in the country and I love being outside, hearing birds and growing things. I like allotments too, even just seeing them from trains. I’ve had this plot for three years now. My shed is made from a packing case used to take an object abroad from the British Museum where I was a curator. I enjoy cultivating flowers so I planted a nature garden. I share my plot with Claire who grows vegetables. Mine is the higgledy-piggledy part.

Andy Pickin – I grew up in Finchley and we moved to Shadwell twenty years ago. We spent eight years in Huntingdon when the firm moved there but most of us came back to London. I wanted an allotment because I’d always had great fun sharing one with my dad. I’ve had the plot for fourteen years. I grew vegetables because money was tight and the first year’s crop was fantastic. Our thirteen children all liked coming here when they were young. The older ones grow their own vegetables now. My wife likes the gardens too, she knows I sometimes come here to get away from the telly or the kids arguing.

Robin & Maria Albert – Robin was in catering before becoming a gardener eight years ago. He was born in Mile End and he’s lived in London all his life. I was born in London too and brought up in Margate. My family is always trying to persuade us to move out to Kent but we like living in Bethnal Green. We grow flowers at home but we wanted somewhere separate for vegetables. The fact that everything is organic is part of the appeal. Producing your own pure food is very satisfying. We have some flowers too and a pond that attracts frogs. I can’t do so much now but I still find gardening very therapeutic.

Ray Newton – I’ve always grown things. I share this plot with Agatha. We grow about a dozen different types of vegetables. It’s all organic. We don’t use pesticides. I retired last year from teaching business studies at Tower Hamlets College. Before that I worked in industry and at one time I was manager of a betting shop. I studied for O and A levels at evening classes and then took a degree course. I became a teacher and taught for twenty-five years. My other interests are local history and football. I’m the secretary of the History of Wapping Trust and a lifelong Millwall supporter.

Will Daly – I was a founder member of the gardens. I was in a nearby pub when Jane came in with another Irish chap and they persuaded me to have a plot. I’ve been in the borough for twenty-seven years. I was born in Ireland and I made a living salmon fishing on a tributary of the Shannon. I came to this country in 1951 and did building work. One of my brothers came over too but he missed the river and went home after a while. I still go back to Ireland but only for weddings and funerals. I can’t do very much gardening now but I love the peace of it.

Raymond Hussey – This is my second year. I live in one of the flats nearby. I’m growing vegetables and learning as I go along. What I’m most proud of is the brussels. And my runner beans were unbelievable. I don’t know whether it’s the soil or me talking to them. Weeds are a problem. Sometimes I’d like to use gallons of weedkiller but we’re not allowed. So I come in and have a chat. I call them everything but weeds. I was born on one of the estates off Brick Lane. I’ve done lots of things including acting. In my last job I was a dustman but I got trapped by the lorry. I still can’t do heavy work so the plot’s a bit of a mess but it’s my little world and I love it.

Robin, Yvonne and Katie Guess – We live at the other end of Cable Street. There’s a small courtyard garden but Yvonne and I were used to growing fruit and vegetables before we lived in London. We love soft fruit, we had a huge crop last year. We grow several vegetables and Yvonne has planted a mixed flower and herb bed. Our daughter Katie likes planting and picking but not weeding. We’re both from the south-east. I’ve been in the East End since 1968 and I worked on the Isle of Dogs as a quality control chemist. Now I’m with the Music Alliance in Oxford Street dealing with composer copyright.

Carl Vella – I came to Tower Hamlets from Malta in 1950 and worked for the NHS, mostly as a fitter and stoker. I’m retired and since I took over the plot four years ago I like to come here every day. I grow mostly vegetables – potatoes and cabbages. I’m on my own now so I give a lot of produce away to an elderly neighbour. I live in the flats nearby and there’s no garden. Coming here stops me getting fed up. I take my dog for a walk, go to the bookie’s and come here. I’d like to bring Pedro more often but he won’t stay in one place.

Sister Elizabeth O’Connor – Our Order has been part of the local community since 1859 and I came to the convent in 1949. After the houses here were demolished the site became a dumping ground until Friends of the Earth initiated the gardens project. When I retired from teaching in 1991, I started gardening here. All the sisters appreciate home grown vegetables and having fresh flowers for the chapel. As a child in County Clare I enjoyed helping my father in our kitchen garden. Apart from the practical use, the gardens are a great place for breaking down barriers and it’s especially good that women can feel safe here on their own.

Graham Kenlin – I was born in Bermuda. My father was a navy chef and had a land-based job working for an admiral. We came back to England when I was four and I grew up in Hackney. I’ve lived in Wapping for thirty-eight years and I’ve had a plot here for about fifteen years. My family have always had allotments. It’s very relaxing but I’m a lazy gardener. I’m an archaeologist and I work abroad sometimes so the plot gets neglected. I’ve had the odd good year but normally I do just enough to stay credible. I like growing large weeds, anything that’s interesting.

Sheila McQuaid – I came across the gardens at an open day. It was such an oasis of green and calm that I put my name down on the spot. Gardening is in the family. My parents were horticulturalists and I grew plants as a child but I’ve only become really interested in the last ten years. We decided on fruit because it’s expensive, especially if you want organic, and it doesn’t need constant attention. I was born and brought up in Cornwall and I’ve lived in Tower Hamlets for twenty-five years. I’m a housing adviser for Camden Council and I work for Stitches in Time on community textile projects.

Anna Girvan and John Griemsman – We’ve had the plot for about ten years. We’re in a 10th floor flat in Limehouse and we wanted somewhere to spend time outside and to grow vegetables. I’m from Belfast and I’ve lived in Limehouse for twenty-five years. John is from Wisconsin and he’s been here for almost thirty years. I work as a librarian in the West End and John is a special needs assistant. I’m more pleased by the flowers in the end than the vegetables. My favourite is a dahlia that Annemarie gave me. It’s a beautiful purple pink and it flowers for such a long time.

Mary Laurencin – I’ve been gardening here for about ten years. A cousin asked me to help then passed the plot on to me. I’d never gardened before but I was suffering from depression and sometimes it was the only place I felt comfortable. I learned to garden mainly by watching television. I’m from St Lucia and I’ve lived in Tower Hamlets for forty years. I came to England in 1962 and at one time I did four jobs every day – I worked in a cafe, had a job at Sainsbury’s, I was a machinist and I did some cleaning. I grow vegetables here. I love flowers but you can’t eat flowers.

Conrad, Donald and James Korek – I garden here with my wife Catherine and our two younger sons, Donald, ten, and James, six. Our eldest boy isn’t interested now. We’ve lived in the borough for fourteen years and started gardening at Cable Street about a year after we arrived. We have a flat nearby and we like to spend time outdoors. I was born in North London and Catherine was brought up on a farm in Scotland, so she has more experience of growing food. James likes weeding and he supports Arsenal. Donald is a West Ham supporter and he’s good at picking up stones and chatting to the other gardeners.

Annemarie Cooper – I’m a supply teacher and I write poetry. I’ve had a plot since 1986. I didn’t know anything about gardening but I love nature and being close to the earth. My dad was a very good vegetable gardener. He and my grandfather shared a plot and they were always arguing about it. I’ve lived in Tower Hamlets for twenty years. When I started here I thought I wanted to grow flowers then I got into vegetables. I love growing sweet peas and big flashy dahlias. Really I like anything that deigns to grow. I enjoy growing tomatoes and digging up potatoes.

Emir Hasham – I’m on the waiting list and until I have a plot I’ll be working on the communal area. My work is computer based graphics and special effects for television and what I like about gardening is the real honest labour and getting my hands dirty. It will be great to grow my own fruit and vegetables My parents used to garden and I helped as a child. I was born in Sheffield. My mum is a Yorkshire lass and my dad is mainly Asian. I’ve lived in Tower Hamlets for twelve years now. I haven’t a garden at home and there’s only so much you can grow on a balcony.

Anwara Begum – I was born in Bangladesh. My father was a businessman and had some land. My seven sisters and I helped mother with the farming. We never had to buy food from the market and we sold bamboo and bananas. When I was sixteen I came to live in Tower Hamlets and ten years ago I started gardening at Cable Street. The four children helped when they were younger but now they are busy with other things. They have to study and help with the housework. I’m studying too – IT, Childcare, Maths and English. And I’m taking Bengali GCSE as well as doing voluntary work in a nursery school.

Joseph Micallef – I first came to the borough from Malta in 1955 and settled here permanently in 1961. I’ve had the plot for ten years. I didn’t know anything about gardening but my father had a farm in Malta so I knew something about agriculture. The vegetables came first and my wife likes the flowers, but I just enjoy seeing things grow and passing the time here. A lot of the produce is given away. You do tend to get too much at once. People look at the plot and think I’m an expert but I’m not, I just plant things and they grow.

Photographs copyright © Chris Kelly

To learn more about Cable Street Community Gardens or buy copies of the Cable St Gardeners book, contact Jane Sill (janesill@aol.com) or visit www.cablestreetcommunitygardens.co.uk

You may also like to take a look at these other photographs by Chris Kelly

Chris Kelly’s Columbia School Portraits 1996

The Cats of Spitalfields (Part One)

The Night I Kissed Joan Littlewood

This is what happens when you try to carry a ladder the wrong way down a narrow alley, as Roy Kinnear is discovering in this frame from Joan Littlewood’s film Sparrows Can’t Sing.

You can see through the arch to Cowley Gardens in Stepney as it was in 1962. This is where Fred (Roy Kinnear’s character) lived with his mother in the film and here his brother Charlie (James Booth) turned up after two years at sea to ask the whereabouts of his wife Maggie (Barbara Windsor), finding that the old terrace in which he lived with Maggie had been demolished in his absence.

The drama revolves around Charlie’s discovery that Maggie has moved into a new tower block with a new man, and his attempts to woo her back. Perhaps there are too many improvised scenes, yet the film has a rare quality – you feel all the characters have lives beyond the confines of the drama, and there is such spirit and genuine humour in all the performances that it communicates the emotional vitality of the society it portrays with great persuasion. In supporting roles, there is Harry H. Corbett, Yootha Joyce, Brian Murphy and several other superb actors who came to dominate television comedy for the next twenty years. Filmed on location around the East End, many locals take turns as extras, including the Krays – Barbara was dating Reggie at the time – who can be seen standing among the customers in the climactic bar room scenes.

My favourite moment in the film is when Charlie searches for Maggie in an old house at the bottom of Cannon St Rd. On the ground floor in an empty room sits an Indian at prayer with his little son, on the first floor some Afro-Caribbeans welcome Charlie into their party and on the top floor Italians are celebrating too. Dan Jones, who lives round the corner in Cable St, told me that this was actually Joan Littlewood’s house where she and Stephen Lewis wrote the screenplay.

I once met Joan Littlewood at an authors’ party hosted by her publisher. She was a frail old lady then but I recognised her immediately by her rakish cap. She was sitting alone in a corner, being ignored by everyone, and looking a little lost. I pointed her out discreetly to a couple of fellow writers but, too awestruck by her reputation, they would not dare approach. Yet I loved her for her work and could not see her neglected, so I walked over and asked if I could kiss her. She consented graciously and, once I had explained why I wanted to kiss her – out of respect and gratitude for her inspirational work – I waved my pals over. We enjoyed a lively conversation but all I remember is that as we said our goodbyes, she took my hand in hers and said ‘I knew you’d be here.’ Although she did not know me or my writing, I understood what she meant and I shall always remember the night I kissed Joan Littlewood.

Watching Sparrows Can’t Sing again recently, I decided to go in search of Cowley Gardens only to discover that it is gone. The street plan has been altered so that where it stood there is not even a road anymore. Just as James Booth’s character returned from sea to find his nineteenth century terrace gone, the twentieth century tower where Barbara Windsor’s character shacked up with the taxi driver has itself also gone, demolished in 1999. Thus, the whole cycle of social and architectural change recorded in this film has been erased.

I hope you can understand why I personally identify with Roy Kinnear and his ladder problem, it is because I too want to go through this same arch and I am also frustrated in my desire – since nowadays there is a solid wall filling the void and preventing me from ever entering. The arch is to be found beneath the Docklands Light Railway between Sutton St and Lukin St. Behind this brick wall, which has been constructed between the past and the present, Barbara Windsor and all the residents of Cowley Gardens are waiting. Now only the magic of cinema can take me there.