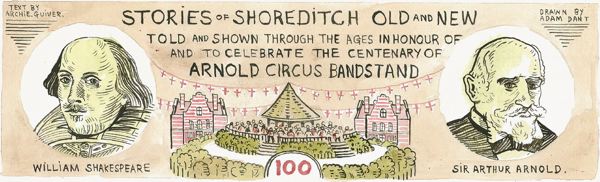

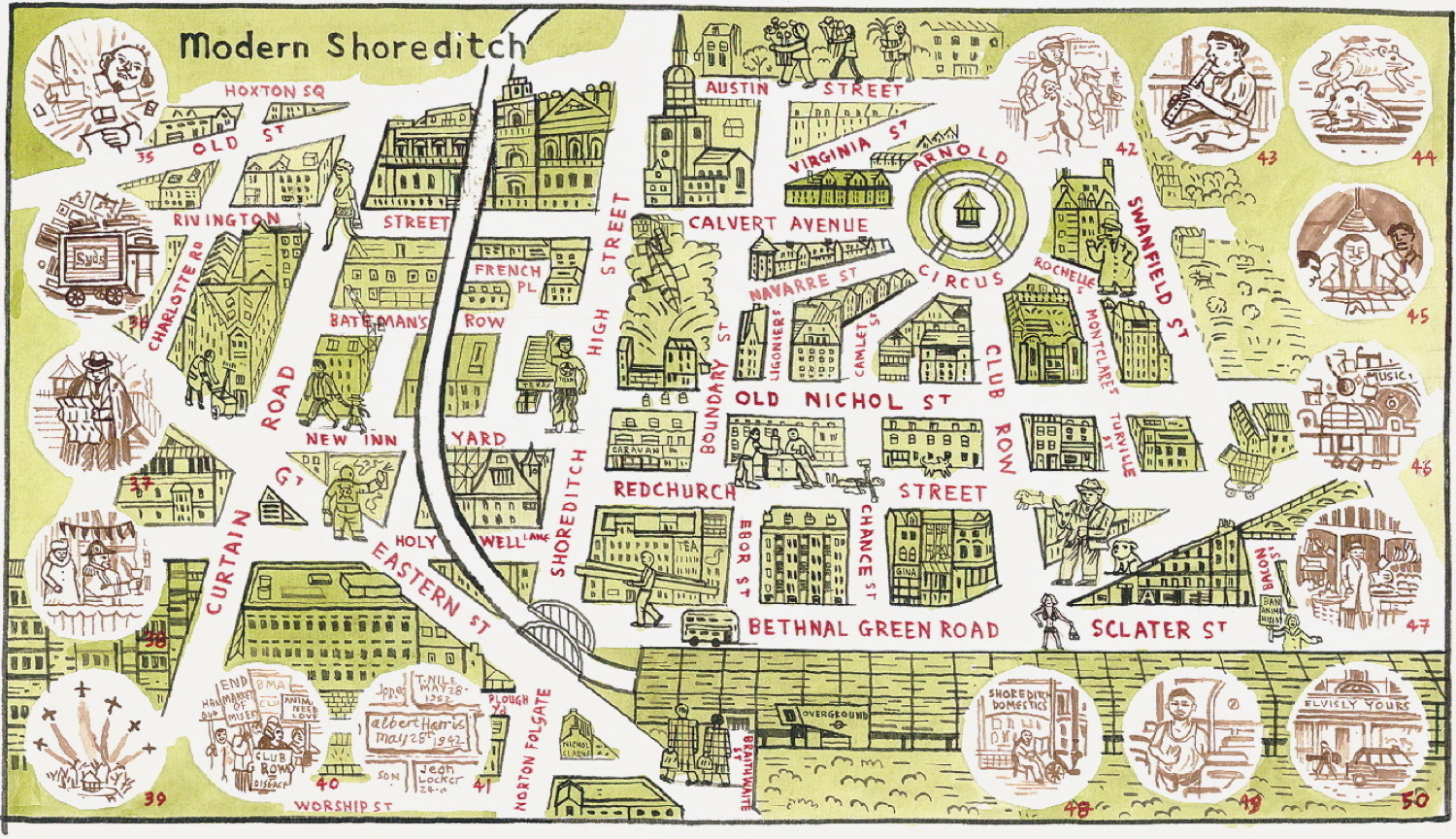

Stories Of Shoreditch Old & New

Each Saturday, we shall be featuring one of Adam Dant’s MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND from the forthcoming book of his extraordinary cartography to published by Spitalfields Life Books & Batsford on June 7th.

Please support this ambitious venture by pre-ordering a copy, which will be signed by Adam Dant with an individual drawing on the flyleaf and sent to you on publication. CLICK TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND BY ADAM DANT

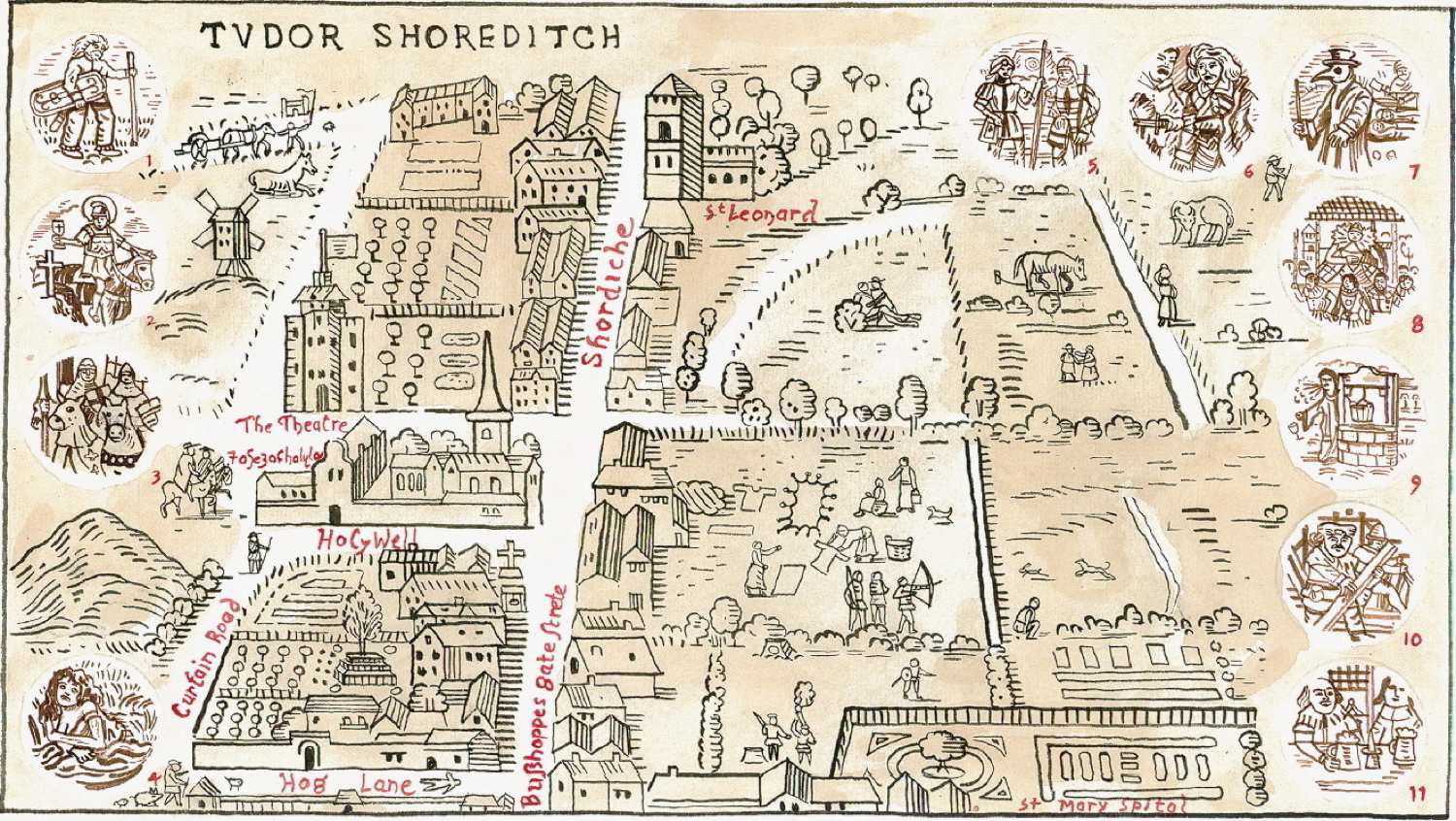

1. Iron Age Man establishes a track along what is now “OLD STREET”.

2. Christian Roman Soldiers worship at the source of the river Walbrook, now St Leonards.

3. Sir John de Soerditch rides against the French Spears alongside The Black Prince.

4. Jane Shore, a goldsmith’s daughter & lover of Edward IV dies in “a ditch of loathsome scent.”

5. “Barlow” the archer is given the dubious title “Duke of Shoreditch” by Henry VIII.

6. Christopher Marlowe murders the son of a Hog Lane innkeeper, he escapes prosecution.

7. Plague burials take place at “Holywell Mound” by the Priory of St John the Baptist at Holywell.

8. Queen Elizabeth I on passing by medieval St Leonards is “Pleased by its Bells.”

9. The sweet water of “The Holywell” is spoilt by manure heaps of local nursery gardens,

10. James Burbage’s sons Cuthbert & Richard dismantle “The Theatre” in two to four days & transport it to the South bank of the Thames where it is rebuilt as “The Globe”.

11. William Shakespeare enjoys a “bumper” at an inn on the site of the present “White Horse.”

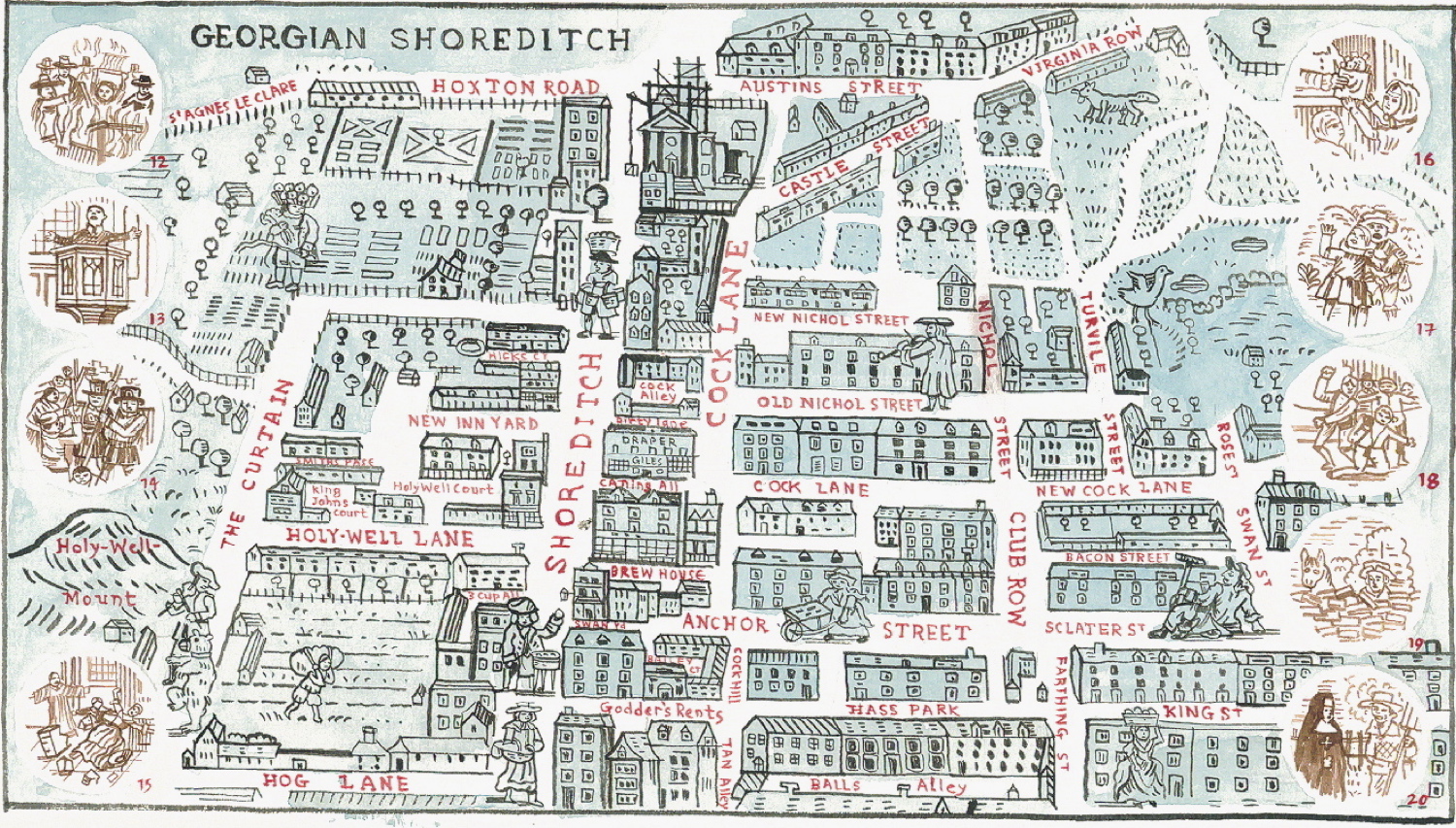

12. Local Huguenot weavers riot for three days protesting against & burning “multi-shuttle looms”.

13. Thomas Fairchild, a gardener, donated £25 to St Leonards for an annual Whitsunday sermon titled “Wonderful Works of God in creation” or “On the certainty of resurrection of the dead proved by certain changes of the animal and vegetable parts of creation.”

14. Militia are called from the Tower to quell four thousand Shoreditch locals rioting against cheap Irish labour being used to build the new George Dance tower of St Leonards.

15. Large lumps of masonry fall onto the congregation during a service at the collapsing old St Leonards.

16. The Huguenot speciality “fish & chips” appear at Britain’s first fish & chip shop on Club Row.

17. The many murders & muggings at Holywell Mount lead to it being levelled.

18. Local theatres such as The Curtain sink to become “no more than sparring rooms.”

19. Brick Lane takes its name from local brickfields, occasional location of furtive criminality.

20. Visitors to James Fryer’s land at Friar’s Mount wrongly assume a monastery stood there.

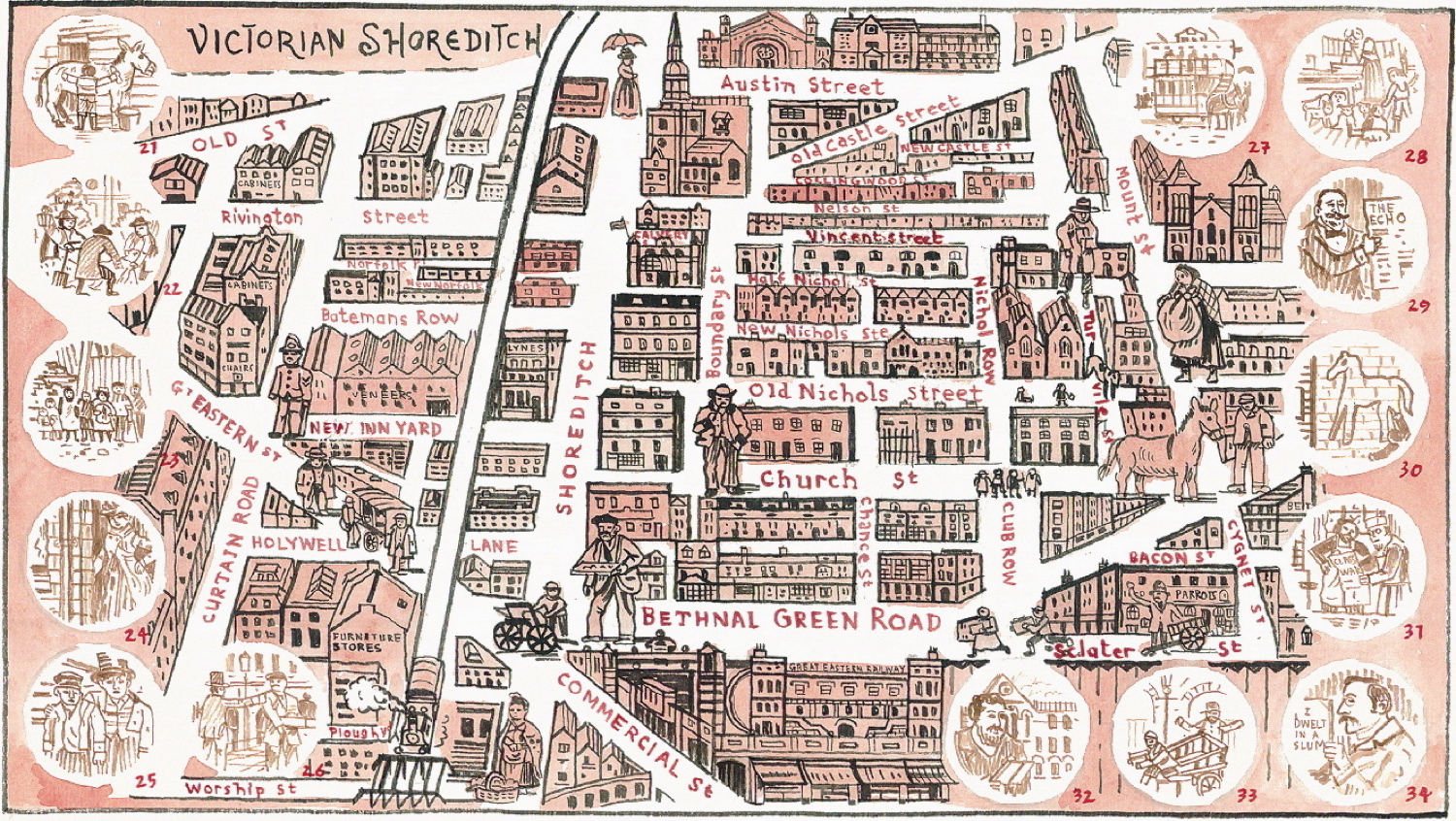

21. Joe Lee, the local horsewhisperer, coaxes improved productivity from working donkeys.

22. “Resurrection Men,” notorious body snatchers pinch recent interred corpses from St Leonards, some coffins in the crypt are found to contain bricks instead of bodies,

23. Four thousand people are dispossessed as Bishopsgate Goods Yard replaces streets around Swan Lane & Leg Alley.

24. Mary Kelly’s funeral procession leaves St Leonards amidst huge crowds. The poor victim of Jack the Ripper is given a second funeral at her own catholic cemetery.

25. Oliver Twist is said to have resided in Shoreditch. Many other unfortunate children arrive each morning at The White St Child Slave Market seeking work.

26. So many unruly pavement-side street vendors populate Shoreditch High St that a regular uniformed Street Keeper is employed.

27. Horse drawn trams add to the general commotion bustle and smell of the High Street.

28. Cats meat sellers, watercress hawkers & dog breeders all cram into the Old Nichol’s filthy tenements.

29. Sir Arthur Arnold, head of the LCC main drainage committee is commemorated at Arnold Circus.

30. For decades the chalk horse on Eastern Counties Railway, Bishopsgate terminus is redrawn by unknown local artist.

31. Enthusiastic Anarchists hoping to bring political awareness to the Old Nichol proletariat through their Boundary St printing operation find the task “like tickling an elephant with a straw.”

32. Artist, Lord Leighton calls the interior of Holy Trinity, Old Nichol St, “The most beautiful in England.”

33. Arthur Harding’s memories of his slum boyhood, “van dragging” etc are recalled in “East End Underworld.”

34. Arthur Morrison pens his slum tale “Child of the Jago” following Reverend Jay’s invitation to the Old Nichol.

35. The chapel dedicated to Shakespeare on Holywell Lane is destroyed by a WWII bomb.

36. Syd’s Coffee Stall, now Hillary Caterers, is saved from destruction during an air raid as two parked buses shelter it from a bomb blast. Thomas Austen’s medieval chancel window is less fortunate.

37. Novelist Arthur Machen identifies a “leyline” running through the mystic ancient earthwork Arnold Circus.

38. King Edward VIII officially inaugurates Boundary Estate from a platform on Navarre St.

39. The Red Arrows pass over the bandstand en-route once more to the Queen’s Birthday.

40. Protestors eventually force the closure of Club Row animal market, once home to dogs, parrots, pigeons and the occasional lion cub.

41. Navarre St is used as a playground by children who carve their names into the brickwork.

42. Artist, Ronald Searle visits Club Row animal market to illustrate Kaye Webb’s “Looking at London.”

43. The resident Bengali flute player of Arnold Circus is often heard across the Boundary Estate on warm Summer evenings.

44. The IRA bomb which explodes on Bishopsgate disturbs the rats in Shoreditch who emerge in large numbers from the drains,

45. The great train robbers plan their notorious crime upstairs in The Ship & Blue Ball, Boundary St.

46. Jeremiah Rotherham demolishes the Shoreditch Music Hall for another warehouse.

47. Joan Rose‘s father proudly displays his fruit & vegetables on Calvert Avenue whilst she is sent to buy more bags at Gardners Market Sundriesmen (still trading today).

48. Every type of vacuum cleaner bag is sold by “Zammo from Grange Hill’s dad” at Shoreditch Domestics on Calvert Avenue.

49. The failed Suicide Bus Bomber is seen by security camera leaving the No 26 at Shoreditch.

50. Mono-recording virtuoso, Liam Watson strides past Shoreditch’s “Elvisly Yours” souvenir shop en-route to legendary Toe-rag recording studios in French Place.

CLICK TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND BY ADAM DANT

Adam Dant’s MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND is a mighty monograph collecting together all your favourite works by Spitalfields Life‘s cartographer extraordinaire in a beautiful big hardback book.

Including a map of London riots, the locations of early coffee houses and a colourful depiction of slang through the centuries, Adam Dant’s vision of city life and our prevailing obsessions with money, power and the pursuit of pleasure may genuinely be described as ‘Hogarthian.’

Unparalleled in his draughtsmanship and inventiveness, Adam Dant explores the byways of English cultural history in his ingenious drawings, annotated with erudite commentary and offering hours of fascination for the curious.

The book includes an extensive interview with Adam Dant by The Gentle Author.

The Departure Of Ken Long

Tomorrow will be Ken Long‘s last day in Chrisp St Market where four generations of his family have traded in fruit and vegetables, so I hope as many readers as possible will take this last opportunity to pay him a visit, pick up supplies for the Easter weekend, and shake the hand of a legendary East End greengrocer.

Photographer Andrew Baker introduced me to his pal Kenny Long at Chrisp St Market in Poplar. Ken is an heroic greengrocer who always sets up his stall earlier than anyone else each day and whose family have been trading in this location through four generations, since before the current market was even built.

For the past thirty years, Ken has been setting up in the dawn, after he has been to the wholesale market to buy fresh produce, wheeling out the old wooden barrows and arranging his stall in the traditional manner with the vegetables to the right and the fruit to left. On his stall sit black and white photographs of those who preceded him, as a reminder of this long-standing family endeavour, which Ken has maintained through his daily ritual out of loving devotion to those who are dead and gone.

While we chatted, Ken popped across the square to place a few bets on the horses, just as he did every day, and our conversation was interrupted by long-standing customers coming to buy. Although Ken made a good living and his work kept him fit and wiry at sixty-one years old, I learnt from him that being a greengrocer is a way of life and a way of understanding the world, as much as it is a business – as much culture as it is commerce.

In Chrisp St Market, Ken Long was the overseer of time passing and the custodian of history.

“It all stems back to before the Second World War when my great-grandmother, Ellen Walton – old granny Walton they used to call her – she had a greengrocer’s shop in Violet Rd in the thirties. My great-grandfather was a merchant seaman and in those days you could bring anything home, and he brought my mum a monkey and they used to have the monkey swinging about in the shop.

When the shop got bombed during the War, they moved onto a stall in Chrisp St Market. Old granny Walton passed the business on to my grandmother, Nell Walton – her name is on my barrow – and from her it went to her son, Freddie Walton and his sister, my mum Joanie Long, worked on the stall fifty years.

In 1951, they moved into the Lansbury Market ( as it was then) on the newly-built Lansbury Estate and we’ve been here ever since. When Uncle Freddie passed away two weeks after his sixty-fifth birthday, my mum took over. By then, I was already working on the fruit stall. My dad, William Long, was a docker and he died when I was eight in 1965. He got killed in the docks. As a child I was up here all the time, I used to come up to my nan on a Saturday and I used to run around the market. I would stay with my nan on a Saturday night and my dad would come and pick me up on a Sunday morning and take me home.

Eventually, I took the stall over from my mum and the licence changed from my uncle into my name but – as far as I was concerned – as long as my mother worked here, she was in charge because I had to do what I was told. At first, I got involved with the vegetable end of the stall, which my aunt used to run with my uncle until she had to have her leg off and couldn’t do it no more. My uncle was going to rent it out but I overheard my mum talking about it and I said, ‘Don’t rent it out to no stranger, keep it in the family. I’ll try it for a couple of years and see how I go’ – and the rest is history. I was thirty-one when I started and this year it will be thirty years that I have been here.

When I started, my uncle let me have the vegetable end of the stall and work it for myself, and I gave him the rent to pay to the council. After about two years, he dropped down dead indoors so we shut the stall up for a week and I had to decide what I was going to do, and I decided to take it on. I had been up to the Spitalfields Market with uncle and seen what he bought and what he didn’t buy. There were four of us working here then – me, my mum, my daughter and a girl. You needed at least three then, but now trade is not what it used to be, so I get by on my own.

For a while now, my stall has been the longest-established here in the market. We’ve been here everyday, every week for as long as this market has existed. Traditionally, people bought their bread, their meat, and their fruit and veg for the weekend on a Friday. Everybody used to cook a roast dinner on a Sunday but there’s not a lot of people that do that anymore. We had customers queueing up from half past six – seven o’clock in the morning and we’d have a queue at either end of the stall. They’d buy their vegetables at one end and pay for them, and then go up to the other end and queue up to buy their fruit. My mum would be serving here, I’d have a girl serving there and I’d be serving in the middle. It was like that all the time, from seven in the morning until four in the afternoon. People who knew me would say, ‘Ken, you know what I have.’ Ten pounds of potatoes, a cabbage, a cauliflower, carrots, onions and parsnips – the whole lot for their roast dinner. Now you get customers who come on a Saturday and ask for two pounds of potatoes, a carrot and a parsnip just to get them by.

Working like I do is a dying trade, serving customers individually and weighing out fruit and veg. On the other stalls in this market and you’ll see ‘pound a bowl’ and ‘pound a bag’ – everything is pre-packed. I am a traditional greengrocer and, although I can get everything all year round now, I know when the seasons are and I know when to buy, and there’s times when I won’t buy certain things because it ain’t proper.

I known greengrocers who have worked in Roman Rd, Watney Market, Bethnal Green and Rathbone Market, packing up and nobody ever replaces them, whereas once upon a time it was family and people came in to the business, taking over from their mum or dad. That’s not happening now.

You don’t have to serve an apprenticeship, you just have to go the wholesale market with whoever you are going to take over from and you have to have some experience to know what you are selling. There’s ten different oranges I can buy, but I know to buy seedless Spanish navels because they are best oranges. Elsewhere in this market, you can buy cheaper oranges and people think it’s better value, but only because they do not understand what they are buying. The soft fruit I sell will ripen nicely, whereas much of the fruit you buy in a supermarket will not ripen until it rots because they select varieties to have a long shelf life.

You don’t always buy with your eyes. Most of my regular customers know me and they say, ‘They look lovely, what are they like?’ and I’ll say, ‘Don’t have them, have these.’ I’ve been doing this long enough to know which people will trust me. I look after my loyal customers.

I enjoy it. I’ve earned a good living. It’s been good to me and it’s been good to all the family over the years. Fifteen years ago, I said ‘When I’m fifty-five, I want to be out.’ That would have been after twenty-five years in the market. But I got to fifty-five and it was still a good living, but by then all my family who worked the stall were dead and gone, and I couldn’t walk away from it. I wouldn’t walk away from a floating ship and it was still is a living to me, but the main reason I carried on was because my conscience told me I could not walk away from it. I could not pack it in because of all the people who came before me. If they saw me walk away for no reason at all, I could see my mum giving me dirty looks, I could see Freddie turning in his grave and I could see my nan. So I thought, ‘No, I’ve got to stick it out.’

In the last couple of years, they have been refurbishing the market and everything is coming down for redevelopment, so I am going now. I’ve got two sheds round the corner which I put these stalls in every night, they’re coming down first before the work starts and that puts me out of a job. There’s nothing I can do about it. I’m being pushed out but it suits me, I’m sixty-one this year. I have been trying to find reasons to go. They’ve offered me alternative accommodation but it won’t be in the vicinity. It only takes me fifteen minutes to pull all these stalls round every morning at present.

We’ve had these old barrows hired off Hiller Brothers since 1951 when we came into the market. I have always paid thirty-seven pounds sixty per month, it never goes up and they maintain them for me at no extra charge.

I’m doing my own thing here. Since my mum’s been gone, and my daughter’s been gone and the girl’s been gone, I did what I liked! As much as I was running the stall, doing the buying and sorting the money out, when they was here I was still ‘the boy.’ It was still – ‘Ken, make us a cup of tea!’ -‘Ken do this!’- ‘Ken do that!’ – ‘Ken, go round the shed and get some orders’ There was three women telling me what to do. It was lovely and I did it because I thought I was supposed to, so I didn’t mind.

I have been serving people I have served for thirty years but I have had new customers come along too. I like the variety. I like being outside. I prefer the winter to the summer, because I don’t want to be here in the summer I want to be somewhere else nice. The hot weather doesn’t help all this stuff, you have to careful what you buy and how much you buy – it makes the job a little but harder. In the winter, you can buy a little bit more because it will keep an extra day or two, and in the winter you sell an even amount of fruit and veg, whereas in the summer you don’t sell a lot of veg because people don’t eat so many hot dinners.

I enjoy the job but – if I am honest – nowadays if I had a shop, I’d be shut at one o’clock because that’s when I start packing up, by two o’clock I am closing down and by three o’clock I am gone. I like getting away in the afternoon. I like getting up in the morning. I like going to the New Spitalfields Market. I like the buzz up the market, buying and running around. Things change all the time with the seasons, so you are always looking around for something different.”

Ken arrives before anyone else to pull his old wooden barrows into the market

Ken sets up his stall in the dawn while the market is empty

Ken’s grandmother Nell Walton is remembered on the side of a barrow made in Wheler St, Spitalfields

Ken’s mother, Joanie Long

Nell Walton & Uncle Freddie

Ellen Walton, known as ‘Old Granny Walton’

Each day Ken enjoys a flutter on the horses

Ken welcomes a long-standing customer

Photographs copyright © Andrew Baker

You may also like to read about

James Ince & Sons, Umbrella Makers

The factory of James Ince & Sons, the oldest established umbrella makers in the country, is one of the few places in London where you will not hear complaints about the rainy weather, because – while our moist climate is such a disappointment to the population in general – it has happily sustained generations of Inces for over two centuries now. If you walked down Whites Row in Spitalfields in 1824, you would have found William Ince making umbrellas and, six generations later, I was able to visit Richard Ince, still making umbrellas in the East End. Yet although the date of origin of the company is conservatively set at 1805, there was a William Inch, a tailor listed in Spitalfields in 1793, who may have been father to William Ince of Whites Row – which makes it credible to surmise that Inces have been making umbrellas since they first became popular at the end of the eighteenth century.

You might assume that the weight of so much history weighs heavily upon Richard Ince, but it is like water off a duck’s back to him, because he is simply too busy manufacturing umbrellas. Richard’s father and grandfather were managers with a large staff of employees, but Richard is one of only four workers at James Ince & Sons today, and he works alongside his colleagues as one of the team, cutting and stitching, personally supervising all the orders. Watching them at work, it was a glimpse of what William Ince’s workshop might have been like in Spitalfields in 1824, because – although synthetics and steel have replaced silk and whalebone, and all stitching is done by machine now – the essential design and manufacturing process of umbrellas remains the same.

Between these two workshops of William Ince in 1824 and Richard Ince in 2011, exists a majestic history, which might be best described as one of gracious expansion and then sudden contraction, in the manner of an umbrella itself. It was the necessity of silk that made Spitalfields the natural home for James Ince & Sons. The company prospered there during the expansion of London through the nineteenth century and the increase in colonial trade, especially to India and Burma. In 1837, they moved into larger premises in Brushfield St and, by 1857, filled a building on Bishopsgate too. In the twentieth century, workers at Inces’ factory in Spitalfields took cover in the basement during air raids, and then emerged to resume making military umbrellas for soldiers in the trenches during the First World War and canvas covers for guns during the Second World War. Luckily, the factory itself narrowly survived a flying bomb, permitting the company to enjoy post-war success, diversifying into angling umbrellas, golfing umbrellas, sun umbrellas and promotional umbrellas, even a ceremonial umbrella for a Nigerian Chief. But in the nineteen eighties, a change in tax law, meaning that umbrella makers could no longer be classed as self-employed, challenged the viability of the company, causing James Ince & Sons to shed most of the staff and move to smaller premises in Hackney.

This is some of the history that Richard Ince does not think about very much, whilst deeply engaged through every working hour with the elegant contrivance of making umbrellas. In the twenty-first century, James Ince & Sons fashion the umbrellas for Rubeus Hagrid and for Mary Poppins, surely the most famous brollies on the planet. A fact which permits Richard a small, yet justly deserved, smile of satisfaction as the proper outcome of more than two hundred years of umbrella making by seven generations of his family. A smile that in its quiet intensity reveals his passion for his calling. “My father didn’t want to do it,” he admitted with a grin of regret, “but I left school at seventeen and I felt my way in. I used to spend my Saturdays in Spitalfields, kicking cabbages around as footballs, and when we had the big tax problem, it taught me that I had to get involved.” This was how Richard oversaw the transformation of his company to become the lean operation it is today. “We are the only people who are prepared to look at making weird umbrellas, when they want strange ones for film and theatre.” he confessed with yet another modest smile, as if this indication of his expertise were a mere admission of amiable gullibility.

On the ground floor of his factory in Vyner St, is a long block where Richard unfurls the rolls of fabric and cuts the umbrella panels using a wooden pattern and a sharp knife. Then he carries the armful of pieces upstairs where they are sewn together before Job Forster takes them and does the “tipping,” consisting of fixing the “points” (which attach the cover to the ends of the ribs), sewing the cover to the frame and adding the tie which is used to furl the umbrella when not in use.

Job was making huge umbrellas, as used by the doormen to shepherd guests through the rain, and I watched as he clamped the bare metal frame to the bench, revolving it as he stitched the cover to each rib in turn, to complete the umbrella. Then came the moment when Job opened it up to scrutinise his handiwork. With a satisfying “thunk,” the black cover expanded like a giant bat stretching its wings taut and I was spellbound by the drama of the moment – because now I understood what it takes to make one, I was seeing an umbrella for the first time, thanks to James Ince & Sons (Umbrella Makers) Ltd.

Richard Ince, seventh generation umbrella maker, prepares to cut covers for brollies.

Job Forster sews the cover to the ribs of the umbrella.

James Ince, born 1816

James John Ince, born 1830

Samuel George Ince, born 1853

Ernest Edward Sears, born 1870

Wilfred Sears Ince, born 1894

Geoffrey Ince, born 1932

Richard Ince, “Prepare for a rainy day!”

New photographs copyright © Chris Hill-Scott

Archive photographs copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

Chris Kelly’s Columbia School Portraits

It is my pleasure to publish Chris Kelly‘s portraits of an entire class at Columbia Primary School, Columbia Rd, Bethnal Green. Distinguished by extraordinary presence and insight, these tender pictures taken twenty-three years ago in 1996 are the outcome of a unique collaboration between the photographer and the schoolchildren. Chris has been taking photographs for education and health services, and voluntary organisations in the East End for almost twenty years, and these astonishing timeless portraits illustrate just one aspect of the work of this fascinating photographer.

I like myself because I am smart and cool and my name is Rufus and Rufus means red one and I really like to play with my friends.

My name is Abdul. I am eight years old. I was born in 7.10.88 and I like trainers called keebok classic.

When I grow up I want to be a singer and travel around the world. My name is Jay and I am eight years old.

My name is Imran. I am eight years old. I like going to school. I like drawing. My sister Happy gives me sweets.

Hello my name is Salma and I was born in 1988. I am eight years old. I like to go to Bangladesh. At school I like Art. I go to Columbia Primary School. And my teachers name is Lucy.

I like myself because I am smart and cool. My name is Ibrahim. My age is eight years old.

My name is Jamal. I go to Columbia School and I am eight years old. I enjoy reading and art and the new book bags. I am special because there are no other people like me.

I’m eight. I like to play. My mummy loves me. My name is Shumin.

I am special because I am good at reading and maths. I am good at running. I am eight years old and I am year three. My address is London E2. My best friend is Rokib. My name is Kamal.

My name is Kamal Miah. I like chocolate cake with chocolate custard. I love computers at home. I learn at Columbia School. Before school I drink fizzy drink and I eat chips. My date of birth is 13.10.88. My best chocolate bar is Lion. My best colour is dark blue. I’m good at maths. Speling group is C.

I am eight years old. My name is Nazneen. I like doing maths and I like doing singing. I have three sisters. And I have lots of friends.

My name is Paplue. I like football and I like fried chicken because they give me chicken. I am eight.

My name is Rahima. I was born in October the eleventh. I’m eight years old. I go to Columbia School. I live in number thirty.

My name is Halil. I am eight years old. I like to play with my three game boys. I like to see funny films.

My name is Litha. I like chocolate. I was born in London. I am eight years old. I live in a flat. When I grow up I want to be a hairdresser.

My name is Robert. I am eight years old and I live in London E2. I like where I live because I have lots of friends to play with.

My name is Rajna. I’m good at running. I do writing at home. And I’m the middle sister.

I am eight years old. I go to school. I play in the playground and my name is Dale.

My name is Sadik. I’m eight years old. I am quite good at football. I practise with my uncle.

My name is Rokib, I am eight years old. I am special because I can read and write and I can do maths and I can be thoughtful and helpful.

My name is Shafia. I am eight years old. I have two sisters. My big sister is called Nazia and my baby sister is called Pinky.

My name is Shokar. I like kick boxing and swimming and I like football.

My name is Urmi and I like going to Ravenscroft Park. I have a black bob cut, browny skin and black eyes. I am eight years old.

My name is Wahidul. I am eight years old. My favourite prehistoric animals are dinosaurs and I like reading and science.

My name is Yousuf. I want to be a computer designer. If I want to be a computer designer I have to be an artist as well.

My name is Ferdous. I am eight years old. I go to Columbia School. My favourite thing is playing games. My date of birth is 10.12.88.

My name is Akthar. I like to go to Victoria Park. I am eight years old.

Hello my name is Fahmida. I am eight years old and I was born in 1989. I like to play skipping and Onit. I like going to school. In school I like Art.

I go to play out with my friends. I go to the shops with my mum. I go to my sisters new house. My name is Ashraf and I’m eight years old.

My name is Fateha. I go to school. I like art. I am eight years old. I am lucky that I’ve got a good art teacher.

Photographs copyright © Chris Kelly

Chris Kelly hopes to make contact with the subjects of these pictures again, now thirty years old, for the purpose of taking a new set of portraits. So, if you were one of these children, please get in touch with chriskellyphoto@blueyonder.co.uk

You may also like to take a look at

Stanley Rondeau, Huguenot

If you visit Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church, Spitalfields on any given Tuesday, you will find Stanley Rondeau – where he works unpaid one day each week, welcoming visitors and handing out guides to the building. The architecture is of such magnificence, arresting your attention, that you might not even notice this quietly spoken white-haired gentleman sitting behind a small table just to the right of the entrance, who comes here weekly on the train from Enfield. But if you are interested in local history, then Stanley is one of the most remarkable people you could hope to meet, because his great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Jean Rondeau was a Huguenot immigrant who came to Spitalfields in 1685.

“When visiting a friend in Suffolk in 1980, I was introduced to the local vicar who became curious about my name and asked me ‘Are you a Huguenot?'” explained Stanley with a quizzical grin.“I didn’t even know what he meant.” he added, revealing the origin of his life-changing discovery,” So I went to Workers’ Educational Association evening classes in Genealogy and that was how it started. I’ve been at it now for thirty years. My own family history came first, but when I learnt that Jean Rondeau’s son John Rondeau was Sexton of Christ Church, I got involved in Spitalfields. And now I come every Tuesday as a volunteer and I like being here in the same building where he was. They refer to me as ‘a piece of living history’, which is what I am really. Although I have never lived here, I feel I am so much part of the area.”

Jean Rondeau was a serge weaver born in 1666 in Paris into a family that had been involved in weaving for three generations. Escaping persecution for his Protestant faith, he came to London and settled in Brick Lane, fathering twelve children. Jean had such success as weaver in London that in 1723 he built a fine house, number four Wilkes St, in the style that remains familiar to this day in Spitalfields. It is a measure of Jean’s integration into British society that his name is to be discovered on a document of 1728 ensuring the building of Christ Church, alongside that of Edward Peck who laid the foundation stone. Peck is commemorated today by the elaborate marble monument next to the altar, where I took Stanley’s portrait which you can see above.

Jean’s son John Rondeau was a master silk weaver and in 1741 he commissioned textile designs from Anna Maria Garthwaite, the famous designer of Spitalfields silks, who lived at the corner of Princelet St adjoining Wilkes St. As a measure of John’s status, in 1745 he sent forty-seven of his employees to join the fight against Bonnie Prince Charlie. Appointed Sexton of the church in 1761 until his death in 1790, when he was buried in the crypt in a lead coffin labelled “John Rondeau, Sexton of this Parish,” his remains were exhumed at the end of twentieth century and transported to the Natural History Museum for study.

“Once I found that the crypt was cleared, I made an appointment at the Natural History Museum, where Dr Molleson showed his bones to me.” admitted Stanley, widening his eyes in wonder. “She told me he was eighty-five, a big fellow – a bit on the chubby side, yet with no curvature of the spine, which meant he stood upright. It was strange to be able to hold his bones, because I know so much about his history.”, Stanley told me in a whisper of amazement, as we sat together, alone in the vast empty church that would have been equally familiar to John the Sexton.

In 1936, a carpenter removing a window sill from an old warehouse in Cutler St that was being refurbished was surprised when a scrap of paper fell out. When unfolded, this long strip was revealed to be a ballad in support of the weavers, demanding an Act of Parliament to prevent the cheap imports that were destroying their industry. It was written by James Rondeau, the grandson of John the Sexton who was recorded in directories as doing business in Cutler St between 1809 and 1816. Bringing us two generations closer to the present day, James Rondeau author of the ballad was Stanley’s great-great-great-grandfather. It was three generations later, in 1882, that Stanley’s grandfather left Sclater St and the East End for good, moving to Edmonton when the railway opened. And subsequently Stanley grew up without any knowledge of Huguenots or the Spitalfields connection, until that chance meeting in 1980 leading to the discovery that he is an eighth-generation British Huguenot.

“When I retired, it gave me a new purpose.” said Stanley, cradling the slender pamphlet he has written entitled, “The Rondeaus of Spitalfields.” “It’s a story that must not be forgotten because we were the originals, the first wave of immigrants that came to Spitalfields,” he declared. Turning the pages slowly, as he contemplated the sense of connection that the discovery of his ancestry has given him, he admitted, “It has made a big difference to my life, and when I walk around in Christ Church today I can imagine my ancestor John the Sexton walking about in here, and his father Jean who built the house in Wilkes St. I can see the same things he did, and when I hear the great eighteenth century organ, I know that my ancestor played it and heard the same sound.”

There is no such thing as an old family, just those whose histories are recorded. We all have ancestors – although few of us know who they were, or have undertaken the years of research Stanley Rondeau has done, bringing him into such vivid relationship with his ancestors. I think it has granted him an enviably broad sense of perspective, seeing himself against a wider timescale than his own life. History has become personal for Stanley Rondeau in Spitalfields.

The silk design at the top was commissioned from Anna Maria Garthwaite by Jean Rondeau in 1742. (5981.9A Victoria and Albert Museum. Photo courtesy of V&A images)

4 Wilkes St built by Jean Rondeau in 1723. Pictured here seen from Puma Court in the nineteen twenties, it was destroyed by a bomb in World War II and is today the site of Suskin’s Textiles.

The copy of James Rondeau’s song discovered under a window sill in Cutler St in 1936.

Stanley Rondeau standing in the churchyard near his home in Enfield, at the foot of the grave of John the Sexton’s son and grandson (the author of the song) both called James Rondeau, and who coincidentally also settled in Enfield.

Arful Nessa’s Sewing Machine

Contributing Writer Delwar Hussain writes a memoir of his mother and her sewing machine

Arful Nessa with her sewing machine table

Rather than the sound of Bow bells, I was born to the whirring of sewing machines in my ear. Throughout most of my childhood, my mother did piecework while my father worked in a sweatshop opposite the beigel shop on Brick Lane, stitching together leather jackets for Mark & Spencer. The factory closed down long ago.

Initially my mother’s industrial-grade Brother sewing machine was in the kitchen, in between the sink and the pine wood table. But it took up too much space there and was also considered dangerous, once ambulatory children started populating the house. It was decided that it would be moved to one of the attic rooms on the top floor of our home, following the custom of the Huguenot silk weavers of the past. There the machine lived and there my mother would be found hunched over it, during all hours of the day and often late into the night. She says it was most hard on her back and shoulders, which would ache from the work.

“The men used to work in the factories. I preferred to do it at home because it was less work compared to what they did. They had to work harder,” she explains, “I began before the children were born. I wasn’t doing much at home, so I thought I should try it and earn a little money. Other women were working as machinists then and an old neighbour who had lived on Parfett St taught me how to operate the machine. I couldn’t do pockets, but I did pleats, belts and hems on skirts for women who worked in offices. I took in work for a factory on Cannon St Rd that made suits and another on New Rd that made blouses.”

For a while my mother sewed the lining into jackets and winter coats, working for a short Sikh man who had a clothes shop on Fournier St. He had quick steps and a bunch of heavy keys dangling from the belt on his trousers. The man still owes her money, she recalls. He would give her wages in arrears, promising to pay, but it never materialised. Following him, she worked for another man, who also did not pay. “Where would you go looking for them today?” my mother asks, “Everyone we used to know around here has left. So much has changed.”

I remember the almost-sweet smell of the machine oil, the thick needles, bundles of colourful nylon yarn, piles and piles of skirts in all shades and sizes, the metal bobbin cases and the sound of the sewing machine. When the foot peddle was down, the vibration could be felt throughout the house. Strangely, this provided a sense of comfort – the knowledge that my mother was upstairs and everything in the world was as it should be.

When I was around twenty, my brothers and sisters and I colluded with each other to get rid of the sewing machine. It had lain dormant in the attic room ever since my mother gave up taking in piecework some years previously. The work had slowly become more irregular and less financially rewarding. “When I first started, I was able to earn around seventy-five pence per skirt, then towards the end, when there were many more women working, it dropped to around ten pence per coat.” These were also the days when much of the manufacturing in East London was being shipped out to parts of the world where there was cheaper labour, including Bangladesh and Turkey.

With my mother’s working paraphernalia left as it was, the space resembled Rodinsky’s room – he was the mythical recluse who once lived a few doors down from us in the attic of 19 Princelet St and who had disappeared one day, leaving everything intact. I had an idea to turn our attic into a study, installing my PC which my mother had bought for me from the money she had saved from sewing. With a separate monitor, keyboard and large hard drive, it was almost as big as her Brother sewing machine.

She had always been a hoarder, so we knew that getting rid of it was going to be a delicate and difficult matter. We had given her prior warnings, but these had fallen on deaf ears. Then one night, when she had gone to bed, my siblings and I crept upstairs and, with a lot of effort, detached the head of the sewing machine from the table. Huffing and puffing, we carried it down three flights of stairs and delicately dumped it at the end of our street. We did the same with the table base.

Of course, she discovered the machine was missing the next day and was incredibly upset. She had “spent one hundred and forty pounds on it,” she said. “It still worked,” she said, “why had we not told her, she could have given it to someone at least, instead of it being thrown away” and “what had she done to deserve children who were so wasteful.” After that, I forgot all about the Brother sewing machine that once lived in our attic.

Recently, I returned from a research trip to Dhaka. I am currently writing a book about the people of that city and had interviewed garment workers about their lives and fears. I came home and was speaking to my mother about it when the subject of her earlier life as a machinist came up. And then she announced her revelation.

My mother and our Somali neighbour had managed to rescue the sewing machine from where my brothers, sisters and I had thought we had discarded the thing. The two women had somehow managed to shuffle the table base along, scraping hard along the pavement. But instead of bringing it back to the house, they took it to the neighbour’s, where it was to stay in the garden until they decided what to do with it. The machine head on the other hand was far too heavy for them to carry and they abandoned it.

This disclosure had to be investigated. My mother and I immediately knocked on our neighbour’s door, and asked if it was still there. The neighbour led us to the garden where, hidden behind wooden boarding and tendrils of ivy, we found the sewing machine my mother had spent so many years working on.

Considering it had endured years outdoors, it looked like it was still in relatively good health. Bits of it, such as the bobbin winder and the spool base were slightly rusty, but the address of the showroom on Cambridge Heath Rd where my mother bought it was clearly labelled and the motor looked in working condition.

She is still upset with my brothers and sisters and me for throwing it away. This confused me. “Why would you want to hold onto something that is a source of oppression?” I asked, high-mindedly. “The machine helped to feed and educate my family,” she answered quietly.

My mother then reminded me that my aunt, her sister, also had a Brother sewing machine and made skirts for many years from her kitchen in Bethnal Green. We went to speak to her. She no longer works as a seamstress and has resorted to keeping her dismembered machine on the veranda of her ground floor flat. The table now stores pots and pans, baskets containing seeds and drying leaves. The head was in the bottom drawer of a metal cabinet next to it, wrapped up in a Sainsbury’s shopping bag. My aunt still has some of the cloth which she would make into skirts and she showed me the pleats on a piece of salmon-coloured material.

“Most of the women in this block worked for different factories and one of them taught me how to do it. I worked for a Turkish man on Mare St for around seven years. I would get started around 7am after the morning prayer at 6am. I can’t remember where the skirts were being sold, but they were for well known shops in the West End. In one day, I could work on fifty or sixty pieces. Some days I made around a hundred. I received around forty or fifty pence per piece and could earn around three hundred pounds per week. But it was all irregular, nothing was fixed. My children would help by cutting the loops off when they got home after school. There is no work anymore, but I kept the machine in case I needed to fix things. It still works.”

While I took notes, sitting on the chair she would sit on whilst working, I could hear dregs of conversation between the two sisters, comparing the quality of oranges in Bethnal Green market to Asda and Iceland, as well as recalling what happened to other women whom they both knew that had worked as seamstresses. This industry, now gone, is a piece of the thread that joins the past with the present in the East End and, in turn, unites the people who have come to make this part of London their home.

My aunt with her sewing machine in Bethnal Green

Arful Nessa

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may like to read Delwar Hussain’s other story about his mother

Chris Skaife, Master Raven Keeper & Merlin The Raven

Chris Skaife & Merlin

Every day at first light, Chris Skaife, Master Raven Keeper at the Tower of London, awakens the ravens from their slumbers and feeds them breakfast. It is one of the lesser known rituals at the Tower, so Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer Martin Usborne & I decided to pay an early morning call upon London’s most pampered birds and send you a report.

The keeping of ravens at the Tower is a serious business, since legend has it that, ‘If the ravens leave the Tower, the kingdom will fall…’ Fortunately, we can all rest assured thanks to Chris Skaife who undertakes his breakfast duties conscientiously, delivering bloody morsels to the ravens each dawn and thereby ensuring their continued residence at this most favoured of accommodations.“We keep them in night boxes for their own safety,” Chris explained to me, just in case I should think the ravens were incarcerated at the Tower like those monarchs of yore, “because we have quite a lot of foxes that get in through the sewers at night.”

First thing, Chris unlocks the bird boxes built into the ancient wall at the base of the Wakefield Tower and, as soon as he opens each door, a raven shoots out blindly like a bullet from a gun, before lurching around drunkenly on the lawn as its eyes accustom to the daylight, brought to consciousness by the smell of fresh meat. Next, Chris feeds the greedy brother ravens Gripp – named after Charles Dickens’ pet raven – & Jubilee – a gift to the Queen on her Diamond Anniversary – who share a cage in the shadow of the White Tower.

Once this is accomplished, Chris walks over to Tower Green where Merlin the lone raven lives apart from her fellows. He undertakes this part of the breakfast service last, because there is little doubt that Merlin is the primary focus of Chris’ emotional engagement. She has night quarters within the Queen’s House, once Anne Boleyn’s dwelling, and it suits her imperious nature very well. Ravens are monogamous creatures that mate for life but, like Elizabeth I, Merlin has no consort. “She chose her partner, it’s me,” Chris assured me in a whisper, eager to confide his infatuation with the top bird, before he opened the door to wake her. Then, “It’s me!” he announced cheerily to Merlin but, with suitably aristocratic disdain, she took her dead mouse from him and flounced off across the lawn where she pecked at her breakfast a little before burying it under a piece of turf to finish later, as is her custom.

“The other birds watch her bury the food, then lift up the turf and steal it,” Chris revealed to me as he watched his charge with proprietorial concern, “They are scavengers by nature, and will hunt in packs to kill – not for fun but to eat. They’ll attack a seagull and swing it round but they won’t kill it, gulls are too big. They’ll take sweets, crisps and sandwiches off children, and cigarettes off adults. They’ll steal a purse from a small child, empty it out and bury the money. They’ll play dead, sun-bathing, and a member of the public will say, ‘There’s a dead raven,’ and then the bird will get up and walk away. But I would not advise any members of the public to touch them, they have the capacity to take off a small child’s finger – not that they have done, yet.”

We walked around to the other side of the lawn where Merlin perched upon a low rail. Close up, these elegant birds are sleek as seals, glossy black, gleaming blue and green, with a disconcerting black eye and a deep rasping voice. Chris sat down next to Merlin and extended his finger to stroke her beak affectionately, while she gave him some playful pecks upon the wrist.

“Students from Queen Mary University are going to study the ravens’ behaviour all day long for three years.” he informed me, “There’s going to be problem-solving for ravens, they’re trying to prove ravens are ‘feathered apes.’ We believe that crows, ravens and magpies have the same brain capacity as great apes. If they are a pair, ravens will mimic each other’s movements for satisfaction. They all have their own personalities, their moods, and their foibles, just like people.”

Then Merlin hopped off her perch onto the lawn where Chris followed and, to my surprise, she untied one of Chris’s shoelaces with her beak, tugging upon it affectionately and causing him to chuckle in great delight. While he was thus entrammelled, I asked Chris how he came to this role in life. “Derrick Coyle, the previous Master Raven Keeper, said to me, ‘I think the birds will like you.’ He introduced me to it and I’ve been taking care of them ever since.“ Chris admitted plainly, opening his heart, “The ravens are continually on your mind. It takes a lot of dedication, it’s early starts and late nights – I have a secret whistle which brings them to bed.”

It was apparent then that Merlin had Chris on a leash which was only as long as his shoelace. “If one of the other birds comes into her territory, she will come and sit by me for protection,” he confessed, confirming his Royal romance with a blush of tender recollection, “She sees me as one of her own.”

“Alright you lot, up you get!”

“A pigeon flew into the cage the other day and the two boys got it, that was a mess.”

“It’s me!”

“She chose her partner, it’s me.”

“She sees me as one of her own.”

Chris Skaife & Merlin

Charles Dickens’ Raven “Grip” – favourite expression, “Halloa old girl!”

Tower photographs copyright © Martin Usborne

Residents of Spitalfields and any of the Tower Hamlets may gain admission to the Tower of London for one pound upon production of an Idea Store card.

You may also like to take a look at these other Tower of London stories

Alan Kingshott, Yeoman Gaoler at the Tower of London

Graffiti at the Tower of London

Beating the Bounds at the Tower of London

Ceremony of the Lilies & Roses at the Tower of London

Bloody Romance of the Tower with pictures by George Cruickshank

John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

Constables Dues at the Tower of London

The Oldest Ceremony in the World

A Day in the Life of the Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London