Adam Dant’s Maps Of London & Beyond

The Map of Spitalfields Life

Generously praising the quality of the books we have published, Richard Bucht, bookseller at Hatchards, described Spitalfields Life Books as ‘the last art publisher.’ Consequently, I am delighted to announce our most ambitious publishing project to date which is a mighty monograph undertaken in proud collaboration with Batsford Books (established 1843).

On June 7th, we are publishing MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND, a spectacular hardback containing all your favourite maps by our Contributing Cartographer, Adam Dant. Large pages allow the reader to study all the astonishing and hilarious details – from gin-sodden drunks brawling in the gutter to the lofty paragons of enlightenment thought – and each plate is annotated with erudite commentary offering hours of fascination for the curious.

MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND includes an interview with the artist by The Gentle Author.

Please support this ambitious venture by pre-ordering a copy, which will be signed by Adam Dant with an individual drawing on the flyleaf and sent to you on publication.

CLICK TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND BY ADAM DANT

Below are a selection of maps from the book

The Map of the Coffee Houses

The Map of Shoreditch as the globe

The Map of Shoreditch as New York

The Map of Shoreditch in the year 3000

The Hackney Treasure Map

The Map of Industrious Shoreditch

The Map of Wallbrook

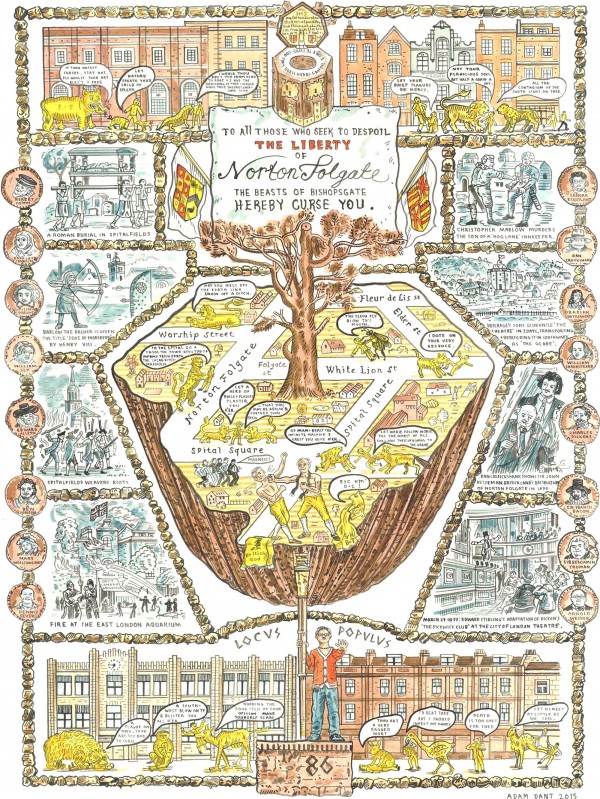

The Map of Norton Folgate

The Map of William Shakespeare’s Shordiche

The Map of Thames Shipwrecks

Maps copyright © Adam Dant

CLICK TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND BY ADAM DANT

Batsford Books, 1893

Bradley Thomas Batsford

Batsford colophon designed by George Kruger Gray

Letitia Batsford

John Stow’s Spittle Fields

At the Bishopsgate Institute, I love to study the 1599 copy of John Stow‘s Survey Of London. As a publisher myself, I find it touching to see the edition that John Stow himself produced, with its delicate type resembling gothic script, and sobering to recognise what a great undertaking it was to publish a book four hundred years ago – requiring every page of type to be set and printed by hand.

Born into a family of tallow chandlers, John Stow became a tailor yet devoted his life to writing and publishing, including an early edition of the works of Geoffrey Chaucer who had lived nearby in Aldgate more than a century earlier. In Stow’s lifetime, the population of London quadrupled and much of the city he knew as a youth was demolished and rebuilt. The sense of grief that he felt to see the city of his youth destroyed inspired him to write and publish his great work – a survey that would record this change for posterity. Consequently, on the title page of the Survey, Stow outlines his intention to include “the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Modern estate and description of that citie.”

Yet in contrast to the dramatic changes he witnessed at first hand, John Stow also described his wonder at the history that was uncovered by the redevelopment, drawing consolation for his sense of loss by setting his life’s experience against the great age of the city and the generations who preceded him in London .

SPITTLE FIELDS

There is a large close called Tasell close sometime, for that there were Tasels planted for the vse of Clothworkers: since letten to the Crosse-bow-makers, wherein they vsed to shoote for games at the Popingey: now the same being inclosed with a bricke wall, serueth to be an Artillerieyard, wherevnto the Gunners of the Tower doe weekely repaire, namely euerie Thursday, and there leuelling certaine Brasse peeces of great Artillerie against a But of earth, made for that purpose, they discharge them for their exercise.

Then haue ye the late dissolued Priorie and Hospitall, commonly called Saint Marie Spittle, founded by Walter Brune, and Rosia his wife, for Canons regular, Walter Archdeacon of London laid the first stone, in the yeare 1197.

On the East side of this Churchyard lieth a large field, of olde time called Lolesworth, now Spittle field, which about the yeare 1576 was broken vp for Clay to make Bricke, in the digging whereof many earthen pots called Vrnae, were found full of Ashes, and burnt bones of men, to wit, of the Romanes that inhabited here: for it was the custome of the Romanes to burne their dead, to put their Ashes in an Vrna, and then burie the same with certaine ceremonies, in some field appoynted for that purpose, neare vnto their Citie: euerie of these pots had in them with the Ashes of the dead, one peece of Copper mony, with the inscription of the Emperour then raigning: some of them were of Claudius, some of Vespasian, some of Nero, of Anthonius Pius, of Traianus, and others: besides those Vrnas, many other pots were there found, made of a white earth with long necks, and handels, like to our stone Iugges: these were emptie, but seemed to be buried ful of some liquid matter long since consumed and soaked through: for there were found diuerse vials and other fashioned Glasses, some most cunningly wrought, such as I haue not seene the like, and some of Christall, all which had water in them, northing differing in clearnes, taste, or sauour from common spring water, what so euer it was at the first: some of these Glasses had Oyle in them verie thicke, and earthie in sauour, some were supposed to haue balme in them, but had lost the vertue: many of those pots and glasses were broken in cutting of the clay, so that few were taken vp whole.

There were also found diuerse dishes and cups of a fine red coloured earth, which shewed outwardly such a shining smoothnesse, as if they had beene of Currall, those had in the bottomes Romane letters printed, there were also lampes of white earth and red, artificially wrought with diuerse antiques about them, some three or foure Images made of white earth, about a span long each of them: one I remember was of Pallas, the rest I haue forgotten.I my selfe haue reserued a mongst diuerse of those antiquities there, one Vrna, with the Ashes and bones, and one pot of white earth very small, not exceeding the quantitie of a quarter of a wine pint, made in shape of a Hare, squatted vpon her legs, and betweene her eares is the mouth of the pot.

There hath also beene found in the same field diuers coffins of stone, containing the bones of men: these I suppose to bee the burials of some especiall persons, in time of the Brytons, or Saxons, after that the Romanes had left to gouerne here. Moreouer there were also found the sculs and bones of men without coffins, or rather whose coffins (being of great timber) were consumed. Diuerse great nailes of Iron were there found, such as are vsed in the wheeles of shod Carts, being each of them as bigge as a mans finger, and a quarter of a yard long, the heades two inches ouer, those nayles were more wondred at then the rest of thinges there found, and many opinions of men were there vttred of them, namely that the men there buried were murdered by driuing those nayles into their heads, a thing vnlikely, for a smaller naile would more aptly serue to so bad a purpose, and a more secret place would lightly be imployed for their buriall.

And thus much for this part of Bishopsgate warde, without the gate.

A copper coin from the Spitalfields Roman Cemetery that I wear around my neck

Bishopsgate Ward entry by John Stow in his Survey of London

Monument to John Stow in St Andrew Undershaft

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Photograph of Stow’s monument copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

You may also like to read about

At Caravanserail

Contributing Writer Rosie Dastgir visits Caravanserail, the new French bookshop in Cheshire St

In the wide shop window of Caravanserail on Cheshire St sit a pair of plush winged armchairs, facing one another over a dimpled copper table as if in silent dialogue. It is a beguiling scene, and I enter to find an elegant new French and English bookshop, café and gallery space in the middle of Spitalfields.

Founded by two French cousins, Anne Vegnaduzzo and Laura Cleary, Caravanserail offers a rendezvous for French and English books, art exhibitions, poetry readings, music and translation events in one space. The name evokes hostelries where travellers and merchants stopped by for the night on their journeys.

“It’s more home than shop,” says Anne, when I remark upon the cosy atmosphere. Behind the counter I spy a set of Hornsea tea and coffee caddies, like the ones we had at home when I was growing up. There are croissants and copper cafetieres, and tea served in blue and white china tea cups for book browsers in search of sustenance.

“Caravanserail is a place to rest,” Laura says, “and it’s also a place to learn and interact for our neighbourhood and those traveling through it.”

The cousins grew up in France, though they have both travelled beyond Europe for work and study. Laura studied Turkish in Istanbul, and considered moving to Turkey before landing a job with the French Embassy in Beirut for six years, and Anne worked in Paris, and then Vancouver, for an artists’ agency

When Laura moved to London in 2015, she felt it was the perfect hub for what they both had in mind, offering a diverse cultural mix in a city that is favourable to start ups and small businesses. The project began incubating during the run up to the Brexit referendum in June 2016.

“We knew it could happen,” Anne tells me, “and then it did, and we opened after that.”

The result did not deter them, they insist.

In December 2016, they decided they wanted to open a book shop together. It was just six months after the referendum, with much talk of a downturn in the economy and a feared exodus of French and other EU nationals.

Were they nervous about opening a business at that moment?

“On the contrary,” Laura says, “it felt more necessary than ever before.”

They began looking around for a place in the East End, attracted by the cultural dynamism of an area with a long history of migration. Like the French Huguenots before them, Laura and Anne are part of a wave of French arrivals in London, a younger crowd who escape the pull of the Lycees in South Kensington and Kentish Town into Bethnal Green, Haggerston, and Spitalfields.

Laura was walking around Spitalfields one day when she came across a former vintage clothes shop. “We stopped by The Society Club next door, and there was a friendly guy there who told us that the premises were available.”

Laura felt at once that this was the one. It was a Saturday, and Anne was in Paris. The cousins had to make a quick decision – the landlord wanted a deposit by Monday. The shop was run down, dark and dingy and neon lit, with a low ceiling, but it was the wide window that convinced them. They imagined the vista of books and art from the street into the shop, the snug for people to sit by the window, sipping coffee and browsing through a book.

That was the coup de foudre moment. The next challenge was how to transform the dilapidated shop into the hybrid platform they had in mind. They drummed up the services of an architect friend in Paris, and within a week or so, he had produced a set of drawings.

“We wanted to have a space where people can hang out, a bookshop and a gallery, and a space for events,” Laura says. Six months later, give or take a few snags, they had it: tawny wooden floors and book shelving, white walls with exposed copper piping snaking around the ceiling, and pockets of bright, warm light. They opened the shop in July 2017, just over a year after the referendum, and have not looked back.

On offer there are book titles in French and English, and international literature translated into English. Laura explains that a big difference between the United Kingdom and France is that there is little translated fiction. Around five per cent of fiction sales here last year came from books in translation, while in France it is closer to fifty per cent. In addition to literature, there are art books, graphic novels and a dedicated section of children’s books, in both languages.

Contemporary art photography is displayed on the walls and the shelving that doubles as a seating area for music, art and literary events in the evenings. First Tuesdays of the month are for spoken word events in collaboration with BoxedIn. More recently, they have introduced a monthly evening on the art of translation, and there are jazz and poetry evenings, and book events for children.

On the day I visit, I am shopping for the birthday of an old friend who is half French. There is a wall of the striking white-spined novels so prominent in classic French bookshops – Madame Bovary is turned out to face me. I cannot quite decide, and select Albert Camus’ L’Etranger for my teenage daughter, who’s studying French A level. Then I notice a select supply of stationery that is hard to resist, and I choose two birthday cards, designed by Letter Press de Paris.

I scan titles in translation and in the original French by authors such as Leila Slimani, whose bestseller, Lullaby, is displayed prominently, and Muriel Barbery’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog. There is the eye-catching graphic novel by Hamid Sulaiman, Freedom Hospital, A Syrian Story. I’m spoilt for choice, but eventually I pick a book on 25 contemporary French artists, and also Lauren Binet’s latest novel in English, The Seventh Function of Language, described by one reviewer as a post-modern hybrid of other texts. It feels right for my half-French, West London dwelling friend.

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Caravanserail, 5 Cheshire St, E2 6ED – open Tuesdays to Sundays.

Rosie Dastgir’s novel, Une Petite Fortune, is published by Editions Bourgois in France and Quercus in the UK.

You may also like to read about

Henry Mayhew, The London Vagabond

Chris Anderson introduces his new biography of Henry Mayhew, The London Vagabond

When Henry Mayhew died in 1887, one newspaper noted ‘The chief impression created in the public mind was one of surprise that he should still be alive.’ Yet nearly forty years earlier, his London Labour & the London Poor had gripped the country, confronting it with the voices of those who had been overlooked. His masterwork began as a series of ‘Letters’ commissioned by The Morning Chronicle and, from 1849 onwards, these grew into a panoramic survey of London’s poorest workers, a long exposure snapshot of mid-nineteenth century life.

The Spitalfields silk weavers were the first group of the working poor Mayhew reported on. Descended from Huguenot refugees, their livelihood was undermined by free trade after the abolition of import tariffs on French silk. Their experience was common among many highly-skilled London workers, as their quality of life deteriorated from the early years of the century, eroded by technological and social change. Late at night, in a narrow Shoreditch street, Mayhew mounted the stairs to a top floor room and visited an old weaver, sick in bed. The weaver lived and worked in a shared top floor room, cobwebbed with sagging clothes lines, where three looms jostled among several beds. The old man asked his daughter, Tilly, to pull up a chair for Mayhew, then began his tale.

“Yes, I was comfortable in ’24. I kept a good little house and I thought, as my young ones growed up – why I thought as I should be comfortable in my old age, and ‘stead of that, I’ve got no wages. I could live by my labour then, but now, why it’s wretched in the extreme. Then I’d a nice little garden and some nice tulips for my hobby, when my work was done. … As for animal food, why it’s a stranger to us. Once a week, may be, we gets a taste of it, but that’s a hard struggle, and many a family don’t have it once a month … Tilly, just turn up that shell now and let the gentlemen see what beautiful fabrics we’re in the habit of producing – and then he shall say whether we ought to be in the filthy state we are. Just show the light, Tilly! That’s for ladies to wear and adorn them. And make them handsome’”

(It was an exquisite piece of maroon coloured velvet. That, amidst all the squalor of the place, seemed marvellously beautiful, and it was a wonder to see it unsoiled amid all the filth that surrounded it).

Mayhew formed a close bond with the Spitalfields silk weavers. Yet The Morning Chronicle fired him after a year – for asking for more work, they said – for speaking up for the workers, Mayhew said. He revived the Letters as his own weekly serial, entitled London Labour & the London Poor. Increasingly, he focused on street folk, costers and other itinerant traders, yet he continued to support the silk weavers cause, even after London Labour ended abruptly in court over unpaid printer’s bills.

On Tuesday 4th May 1852 at the school room, St John’s St, Brick Lane, The Trade Society for the Protection of Native Industry convened a mass meeting to ‘adopt resolutions condemnatory of the present unregulated and stimulated system of competition, which is reducing the working classes of this country to the continental level’. Mayhew came on stage to loud cheering. He told how he had commenced his ‘inquiries into the state of the working classes, being at the time an inveterate Free-trader’ with The Morning Chronicle, but his research among the poor had converted him to protectionism.

Mayhew returned to Spitalfields for a very different occasion four years later, as part of his second major series, The Great World of London. On the evening of 8th April 1856, he summoned a gathering of professional villains, the ‘Swell Mobsmen’ at the White Lion Tavern, Fashion St. Entry was by ticket only, signed by Mayhew and stating the police were barred. A hundred crooks gathered in the well-lit, comfortable room where a ‘free and easy’ atmosphere prevailed.

“A stranger would have had no suspicion that the men there assembled were at war with society. They one and all appeared well fed, well clad, and at ease with themselves. In the course of the evening several showily-dressed youths, who were evidently the ‘aristocracy’ of the class, walked into the room. These were mainly habited as clerks or young men in offices, some wearing gold guard chains, others with pistol keys dangling from their waistcoat pockets, and having diamond pins in their cravats. They were, however, all ‘mobsmen,’ as they are called – men who in some instances, we are assured, are gaining their £10 or even £20 a week by light-fingered operations. Indeed, several present were pointed out as ‘tip-top sawyers,’ ‘moving in the best society and doing a heavy business’. Beside those there were a few notorious ‘cracksmen’ (house-breakers) and one or two ‘fences’ (receivers of stolen goods), who were said to be worth their weight in gold.”

Mayhew proposed a society to help these people to go straight. In the event, most of the Swell Mobsmen seemed appreciative but unpersuaded.

“A few candidly stated ‘they didn’t seem to care’ about reforming themselves, but they would gladly assist any of their body who was desirous of so doing.”

A unique exploration of working Londoners, London Labour & the London Poor influenced an entire generation of writers, Charles Dickens among them. A pioneering work of social science, criminology and oral history, it was a century ahead of its time, yet within a few years of Mayhew’s death the work was all but forgotten, along with its author.

Only when the great metropolis that Mayhew loved lay in ruins after the Blitz did London Labour & the London Poor resurface. By the late sixties, all four volumes were available once more, riding the wave of a Victorian revival. ‘It is a book’, wrote W. H. Auden in 1968, ‘in which one can browse for a lifetime without exhausting its treasures.’ Yet a veil remained over Mayhew and, by the seventies, as academics fought over the meaning of his legacy, the historian E. P. Thompson observed:

“He was the subject of no biography and there is something like a conspiracy of silence about him in some of the reminiscences and biographies of his contemporaries … Mayhew remains a puzzling character and some final clue seems to be missing.”

By the eighties, when London Labour & the London Poor had become established as a fixture on the reading list for courses on literature, history, criminology, culture studies and more, the Penguin edition could still open with, ‘It is strange that not more is known about the life of Henry Mayhew.’ Today, Mayhew crops up on the National Curriculum, feted as a philanthropist. His work inspires novels and films exploring the lost world of Victorian London. Terry Pratchet dedicated his final novel, Dodger, to Mayhew. Even so, his life has remained shrouded – until now.

Born into a wealthy family, Mayhew’s public school years were cut short and he was shipped off to Calcutta as a midshipman. Taken on at his father’s law firm upon his return, he left when – absentmindedly – he got his father arrested. Then he became a journalist and dramatist in eighteen-thirties London, neither considered respectable occupations, crowning the decade by founding Punch. It became the most successful magazine of the century and should have set him up for life.

Instead, his path led to bankruptcy and prison. He spent years in exile in Guernsey and Germany. In between, he became famous for his revelations about the poor and brought out London Labour & the London Poor in 1851. He was a respected children’s author, a popular comic novelist, a criminologist who gave evidence to Parliamentary Select committees and a war correspondent. He wrote for the stage, tried to enter politics, the darling of both radicals and conservatives for attacking the liberal mantra of Free Trade. He was known as a philosopher and as a scientist, who revered his friend Michael Faraday, and sought to bring electric lighting to London decades before it arrived.

Mental illness haunted him though, his periodic peaks alternating with deep troughs. He mixed with Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray and stood at the centre of the burgeoning literary world, met with government ministers to advocate social reforms, and mingled with costers, dockers and the underworld too, keeping an open house for thieves and paroled prisoners. His closeness to some of them backfired in blackmail and death threats. His wife, Jane Jerrold, who dealt with the bailiffs for him and secretly co-wrote much of his work, left him when their children had grown up and insisted on being buried under her maiden name. Forgotten, Henry Mayhew spent his last decades moving from one Bloomsbury bedsit to another, plotting new schemes and new books, even until the very last.

The Oyster Stall. “I’ve been twenty years and more, perhaps twenty-four, selling shellfish in the streets. I was a boot closer when I was young, but I had an attack of rheumatic fever, and lost the use of my hands for my trade. The streets hadn’t any great name, as far as I knew, then, but as I couldn’t work, it was just a choice between street selling and starving, so I didn’t prefer the last. It was reckoned degrading to go into the streets – but I couldn’t help that. I was astonished at my success when I first began, I made three pounds the first week I knew my trade. I was giddy and extravagant. I don’t clear three shillings a day now, I average fifteen shillings a week the year through. People can’t spend money in shellfish when they haven’t got any.”

The Irish Street-Seller. “I was brought over here, sir, when I was a girl, but my father and mother died two or three years after. I was in service, I saved a little money and got married. My husband’s a labourer, he’s out of worruk now, and I’m forced to thry and sill a few oranges to keep a bit of life in us, and my husband minds the children. Bad as I do, I can do a penny or tuppence a day better profit than him, poor man! For he’s tall and big, and people thinks, if he goes round with a few oranges, it’s just from idleniss.”

The Groundsel Man. “I sell chickweed and grunsell, and turfs for larks. That’s all I sell, unless it’s a few nettles that’s ordered. I believe they’re for tea, sir. I gets the chickweed at Chalk Farm. I pay nothing for it. I gets it out of the public fields. Every morning about seven I goes for it. I’ve been at business about eighteen year. I’m out till about five in the evening. I never stop to eat. I am walking ten hours every day – wet and dry. My leg and foot and all is quite dead. I goes with a stick.”

The Baked Potato Man. “Such a day as this, sir, when the fog’s like a cloud come down, people looks very shy at my taties. They’ve been more suspicious since the taty rot. I sell mostly to mechanics, I was a grocer’s porter myself before I was a baked taty. Gentlemen does grumble though, and they’ve said, “Is that all for tuppence?” Some customers is very pleasant with me, and says I’m a blessing. They’re women that’s not reckoned the best in the world, but they pays me. I’ve trusted them sometimes, and I am paid mostly. Money goes one can’t tell how, and ‘specially if you drinks a drop as I do sometimes. Foggy weather drives me to it, I’m so worritted – that is, now and then, you’ll mind, sir.”

The London Coffee Stall. “I was a mason’s labourer, a smith’s labourer, a plasterer’s labourer, or a bricklayer’s labourer. I was for six months without any employment. I did not know which way to keep my wife and child. Many said they wouldn’t do such a thing as keep a coffee stall, but I said I’d do anything to get a bit of bread honestly. Years ago, when I as a boy, I used to go out selling water-cresses, and apples, and oranges, and radishes with a barrow. I went to the tinman and paid him ten shillings and sixpence (the last of my savings, after I’d been four or five months out of work) for a can. I heard that an old man, who had been in the habit of standing at the entrance of one of the markets, had fell ill. So, what do I do, I goes and pops onto his pitch, and there I’ve done better than ever I did before.”

Coster Boy & Girl Tossing the Pieman. To toss the pieman was a favourite pastime with costermonger’s boys. If the pieman won the toss, he received a penny without giving a pie, if he lost he handed it over for nothing. “I’ve taken as much as two shillings and sixpence at tossing, which I shouldn’t have done otherwise. Very few people buy without tossing, and boys in particular. Gentlemen ‘out on the spree’ at the late public houses will frequently toss when they don’t want the pies, and when they win they will amuse themselves by throwing the pies at one another, or at me. Sometimes I have taken as much as half a crown and the people of whom I had the money has never eaten a pie.”

The Street- Seller of Nutmeg Graters. “Persons looks at me a good bit when I go into a strange place. I do feel it very much, that I haven’t the power to get my living or to do a thing for myself, but I never begged for nothing. I never thought those whom God had given the power to help themselves ought to help me. My trade is to sell brooms and brushes, and all kinds of cutlery and tinware. I learnt it myself. I was never brought up to nothing, because I couldn’t use my hands. Mother was a cook in a nobleman’s family when I was born. They say I was a love child. My mother used to allow so much a year for my schooling, and I can read and write pretty well. With a couple of pounds, I’d get a stock, and go into the country with a barrow, and buy old metal, and exchange tinware for old clothes, and with that, I’m almost sure I could make a decent living.”

The Crockery & Glass Wares Street-Seller. “A good tea service we generally give for a left-off suit of clothes, hat and boots. We give a sugar basin for an old coat, and a rummer for a pair of old Wellington boots. For a glass milk jug, I should expect a waistcoat and trowsers, and they must be tidy ones too. There is always a market for old boots, when there is not for old clothes. I can sell a pair of old boots going along the streets if I carry them in my hand. Old beaver hats and waistcoats are worth little or nothing. Old silk hats, however, there’s a tidy market for. There is one man who stands in Devonshire St, Bishopsgate waiting to buy the hats of us as we go into the market, and who purchases at least thirty a week. If I go out with a fifteen shilling basket of crockery, maybe after a tidy day’s work I shall come home with a shilling in my pocket and a bundle of old clothes, consisting of two or three old shirts, a coat or two, a suit of left-off livery, a woman’s gown maybe or a pair of old stays, a couple of pairs of Wellingtons, and waistcoat or so.”

The Blind Bootlace Seller. “At five years old, while my mother was still alive, I caught the small pox. I only wish vaccination had been in vogue then as it is now or I shouldn’t have lost my eyes. I didn’t lose both my eyeballs till about twenty years after that, though my sight was gone for all but the shadow of daylight and bright colours. I could tell the daylight and I could see the light of the moon but never the shape of it. I never could see a star. I got to think that a roving life was a fine pleasant one. I didn’t think the country was half so big and you couldn’t credit the pleasure I got in going about it. I grew pleaseder and pleaseder with the life. You see, I never had no pleasure, and it seemed to me like a whole new world, to be able to get victuals without doing anything. On my way to Romford, I met a blind man who took me in partnership with him, and larnt me my business complete – and that’s just about two or three and twenty year ago.”

The Street Rhubarb & Spice Seller. “I am one native of Mogadore in Morocco. I am an Arab. I left my countree when I was sixteen or eighteen years of age, I forget, sir. Dere everything sheap, not what dey are here in England. Like good many, I was young and foolish – like all dee rest of young people, I like to see foreign countries. The people were Mahomedans in Mogadore, but we were Jews, just like here, you see. In my countree the governemen treat de Jews very badly, take all deir money. I get here, I tink, in 1811 when de tree shilling pieces first come out. I go to de play house, I see never such tings as I see here before I come. When I was a little shild, I hear talk in Mogadore of de people of my country sell de rhubarb in de streets of London, and make plenty money by it. All de rhubarb sellers was Jews. Now dey all gone dead, and dere only four of us now in England. Two of us live in Mary Axe, anoder live in, what dey call dat – Spitalfield, and de oder in Petticoat Lane. De one wat live in Spitalfield is an old man, I dare say going on for seventy, and I am little better than seventy-three.”

The Street-Seller of Walking Sticks. “I’ve sold to all sorts of people, sir. I once had some very pretty sticks, very cheap, only tuppence a piece, and I sold a good many to boys. They bought them, I suppose, to look like men and daren’t carry them home, for once I saw a boy I’d sold a stick to, break it and throw it away just before he knocked at the door of a respectable house one Sunday evening. There’s only one stick man on the streets, as far as I know – and if there was another, I should be sure to know.”

The Street Comb Seller. “I used to mind my mother’s stall. She sold sweet snuff. I never had a father. Mother’s been dead these – well, I don’t know how long but it’s a long time. I’ve lived by myself ever since and kept myself and I have half a room with another young woman who lives by making little boxes. She’s no better off nor me. It’s my bed and the other sticks is her’n. We ‘gree well enough. No, I’ve never heard anything improper from young men. Boys has sometimes said when I’ve been selling sweets, “Don’t look so hard at ’em, or they’ll turn sour.” I never minded such nonsense. I has very few amusements. I goes once or twice a month, or so, to the gallery at the Victoria Theatre, for I live near. It’s beautiful there, O, it’s really grand. I don’t know what they call what’s played because I can’t read the bills. I’m a going to leave the streets. I have an aunt, a laundress, she taught me laundressing and I’m a good ironer. I’m not likely to get married and I don’t want to.”

The Grease-Removing Composition Sellers. “Here you have a composition to remove stains from silks, muslins, bombazeens, cords or tabarets of any kind or colour. It will never injure or fade the finest silk or satin, but restore it to its original colour. For grease on silks, rub the composition on dry, let it remain five minutes, then take a clothes brush and brush it off, and it will be found to have removed the stains. For grease in woollen cloths, spread the composition on the place with a piece of woollen cloth and cold water, when dry rub it off and it will remove the grease or stain. For pitch or tar, use hot water instead of cold, as that prevents the nap coming off the cloth. Here it is. Squares of grease removing composition, never known to fail, only a penny each.”

The Street Seller of Birds’ Nests. “I am a seller of birds’-nesties, snakes, slow-worms, adders, “effets” – lizards is their common name – hedgehogs (for killing black beetles), frogs (for the French – they eats ’em), and snails (for birds) – that’s all I sell in the Summertime. In the Winter, I get all kinds of of wild flowers and roots, primroses, buttercups and daisies, and snowdrops, and “backing” off trees (“backing,” it’s called, because it’s used to put at the back of nosegays, it’s got off yew trees, and is the green yew fern). The birds’ nests I get from a penny to threepence a piece for. I never have young birds, I can never sell ’em, you see the young things generally die of cramp before you can get rid of them. I gets most of my eggs from Witham and Chelmsford in Essex. I know more about them parts than anybody else, being used to go after moss for Mr Butler, of the herb shop in Covent Garden. I go out bird nesting three times a week. I’m away a day and two nights. I start between one or two in the morning and walk all night. Oftentimes, I wouldn’t take ’em if it wasn’t for the want of the victuals, it seems such a pity to disturb ’em after they made their little bits of places. Bats I never take myself – I can’t get over ’em. If I has an order of bats, I buys ’em off boys.”

The Street-Seller of Dogs. “There’s one advantage in my trade, we always has to do with the principals. There’s never a lady would let her favouritist maid choose her dog for her. Many of ’em, I know dotes on a nice spaniel. Yes, and I’ve known gentleman buy dogs for their misses. I might be sent on with them and if it was a two guinea dog or so, I was told never to give a hint of the price to the servant or anybody. I know why. It’s easy for a gentleman that wants to please a lady, and not to lay out any great matter of tin, to say that what had really cost him two guineas, cost him twenty.”

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

New Hope For Trinity Green Almshouses

Three years ago, I reported upon the sorry neglect that has occurred in recent years – under the stewardship of Tower Hamlets Council – of the Grade 1 listed Trinity Green Almshouses in Whitechapel designed by Sir Christopher Wren. The outcome of my article was the formation of the Friends of Trinity Green which has been instrumental in challenging Sainsbury’s plan to build a tower of luxury flats overshadowing the almshouses.

Yet no improvement to the maintenance of Trinity Green has resulted. Buildings that were decaying then are decaying still and the vacant Council-owned flat remains empty after all this time.

At the Cabinet Meeting today, Tower Hamlets Council members are discussing selling off the empty cottage at auction. In response, The Spitalfields Trust is offering to buy it and the entire site from the Council, taking on complete responsibility for the maintenance of Trinity Green and giving it a sustainable future. They propose creating an independent buildings preservation trust that would use income from rents and grants available to such heritage trusts to maintain the property and manage it in perpetuity.

Below you can read The Spitalfields Trust letter and, if you wish to support this initiative, please write today to John Biggs, Mayor of Tower Hamlets: john.biggs@towerhamlets.gov.uk

THE SPITALFIELDS TRUST

18 Folgate Street,

London E1 6BX

Cabinet Meeting – 20th March 2018

Regarding the disposal of 2 Trinity Green, Mile End Rd

Dear Mayor Biggs & Cabinet Members,

I am writing to you in relation to Trinity Green, one of the most important groups of Grade I listed buildings in London; buildings which are critical in the architectural history of London and which played an important role in the development of the conservation movement in Britain.

I attach our previous letter dated the 13th April 2016 in which we outlined our concerns surrounding the condition of the buildings and the lack of a comprehensive plan for their future management – a concern which is also shared by a number of other conservation and heritage groups.

Subsequent to this letter, we met onsite with Council officers and encouraged them to produce condition reports which we saw as an important first step to finding a comprehensive solution.

We are surprised that paragraph 3.17 of the report issued last Thursday 15th makes no mention of The Spitalfields Trust, nor of our initial approach which has led to this outcome. Indeed we would not have been aware of the report’s existence but for the intervention of The Friends of Trinity Green.

The Spitalfields Trust are still ready, willing and able – for the reasons set out in our previous letter – to engage with the Council. But we feel that there is a lack of understanding on the part of officers of the complexity of the situation and a lack of willingness to work with us to find a potential solution. It seems that this will now require direction and leadership from Councillors and the Mayor.

We feel that the proposed sale will impact adversely on finding a strategy for the site as a whole. It is obvious that only one comprehensive strategy can produce a durable solution, thus relieving the council of its significant obligations.

We estimate the restoration of the Chapel will cost £500,000, while the street frontage and green will cost £100,000. The notion that the Council will be able to cover this cost or be able to carry out the specialist work required is not realistic.

Consequently, The Spitalfields Trust would like to propose a comprehensive plan for the restoration and protection of Trinity Green which will be cost effective to the Council and will relieve it of its current and long-term obligations.

- We are prepared to purchase the site as a whole from Tower Hamlets Homes, to restore it fully.

- We are prepared to take on responsibility for the common parts of Trinity Green and to develop and carry out a comprehensive restoration plan for the common parts (e.g. the gates) of the buildings.

- We would transfer the common parts to a newly created buildings preservation trust, including the current owners of the buildings, which would be responsible for their long-term maintenance.

The Council is obliged as a best value authority under section 3 of the Local Government Act 1999 to “make arrangements to secure continuous improvement in the way in which its functions are exercised having regard to a combination of economy, efficiency and effectiveness.”

Selling No.2 at auction, with no provision to mitigate the short-term repairs or future expense of maintaining Trinity Green would be a short-sighted move. The Trust would not be prepared to purchase No 2 in isolation and instead proposes an overall strategy which takes into account the considerable cost of restoring the chapel and common areas which have been badly neglected.

We would like the opportunity to continue the dialogue begun in 2016, to meet and find an effective and durable solution.

Yours faithfully

Patrick Streeter

Chairman, The Spitalfields Trust

While this council owned cottage sits empty, the water tank has leaked for years damaging brick work

Council owned cottage to the left and privately owned cottage to the right reveal comparative levels of maintenance

Unappreciated interior of the chapel, where seventeenth century chandeliers have been removed leaving just the chains

This stone ball was removed from the roof of a council owned cottage and never replaced, meanwhile a vent punctures the cornice of this grade 1 listed building

After three hundred years, the hands have been removed from the clock face

Trinity Almshouses, Mile End Rd, 1695

Click here to learn more about the FRIENDS OF TRINITY GREEN

You may also like to read about

A Walk Through Time In Spitalfields Market

Once upon a time, the Romans laid out a graveyard along the eastern side of the road leading north from the City of London, in the manner of the cemetery lining the Appian Way. When the Spitalfields Market was demolished and rebuilt in the nineteen-nineties, stone coffins and funerary urns with copper coins were discovered beneath the market buildings – a sobering reminder of the innumerable people who came to this place and made it their own over the last two thousand years. Outside the City, there is perhaps no other part of London where the land bears the footprint of so many over such a long expanse of time as Spitalfields.

In his work, Adam Tuck plays upon this sense of reverberation in time by overlaying his own photographs upon earlier pictures to create subtly modulated palimpsests, which permit the viewer to see the past in terms of the present and the present in terms of the past, simultaneously. He uses photography to show us something that is beyond the capability of ordinary human vision, you might call it God’s eye view.

Working with the pictures taken by Mark Jackson & Huw Davies in 1991, recording the last year of the nocturnal wholesale Fruit & Vegetable Market before it transferred to Leyton after more than three centuries in Spitalfields, Adam revisited the same locations to photograph them today. The pictures from 1991 celebrate the characters and rituals of life within a market community established over generations, depicted in black and white photographs that, at first glance, could have been taken almost any time during the twentieth century.

In Adam Tuck’s composites, the people in the present inhabit the same space as those of the past, making occasional surreal visual connections as if they sense each others presence or as if the monochrome images were memories fading from sight. For the most part – according to the logic of these images – the market workers are too absorbed in their work to be concerned with time travellers from the future, while many of the shoppers and office workers cast their eyes around aimlessly, unaware of the spectres from the past that surround them. Yet most telling are comparisons in demeanour, which speak of self-possession and purpose – and, in this comparison, those in the past are seen to inhabit the place while those in the present are merely passing through.

Although barely more than a quarter cenury passed since the market moved out, the chain stores and corporate workers which have supplanted it belong to another era entirely. There is a schism in time, since the change was not evolutionary but achieved through the substitution of one world for another. Thus Adam’s work induces a similar schizophrenic effect to that experienced by those who knew the market before the changes when they walk through it today, raising uneasy comparisons between the endeavours of those in the past and the present, and their relative merits and qualities.

Brushfield St, north side.

Lamb St, south side.

Brushfield St, looking east.

In Brushfield St.

In Gun St.

Brushfield St, looking south-east.

Looking out from Gun St across Brushfield St.

In Brushfield St.

Market interior.

Northern corner of the market.

In Lamb St.

Lamb St looking towards The Golden Heart.

Photographs copyright © Mark Jackson & Huw Davies & Adam Tuck

Mark Jackson & Huw Davies photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to look at more of Adam Tuck’s work

A Walk Through Time in Spitalfields

and Mark Jackson & Huw Davies pictures of the Spitalfields Market

Spitalfields Market Portraits, 1991

Night at the Spitalfields Market, 1991

Mark Jackson & Huw Davies’ Photographs of the Spitalfields Market

At The Pet Cemetery

Now that I have recovered from my chill, I thought I might venture an excursion on a rare day of sunlight last week and fulfil my long-held ambition to visit the pet cemetery in Ilford.

While I lay sick in my bed, watching the snow falling outside the window, I was keenly aware of the empty space at my feet and, when I rose and sat by the stove, there was an absence at the hearth where my old cat Mr Pussy once lay. Six months since his demise, I discovered a curiosity to view the garden of remembrance where more three thousand of his fellow creatures lie interred and see how they have been memorialised by adoring owners as a means to assuage their sense of loss.

It is a commonplace to observe the peace that prevails in a cemetery yet this was my first impression, provoked by the thought of the cacophonous din that would result if all these dogs, cats, pigeons and budgies were confined together within this space while they were alive. On closer examination, the collective emotionalism of so many affectionate elegies upon the gravestones expressing both gratitude and grief for dead pets is overwhelming. Especially as most of the owners who placed these monuments are dead too – including Sir Bruce Forsyth whose beloved collie Rusty is interred here.

Between the twenties and the sixties, animals were buried continuously in this quiet corner of Redbridge but then the cemetery was closed and fell into neglect until 2007, when it was reopened with a celebratory fly-past of racing pigeons and a military ceremony by the King’s Rifle Corps. Especially noticeable today are the white marble headstones for heroic animals, carrier pigeons that delivered vital wartime messages, dogs that rescued survivors from buildings in the Blitz and ships’ cats that killed rats on naval vessels.

Yet in spite of the heroism of animals in war and the depth of feeling evinced by domestic pets, the cemetery is quite a modest affair, just the corner of a field hidden behind the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals. Curiously, many of the owners attribute themselves as ‘Mother’ and ‘Father’ on the gravestones, declaring a relationship to their pets that was parental and a bereavement which registered as the loss of a member of the family.

Animals surprise us by discovering and occupying a particular intimate emotional space close to our hearts that we did not realise existed until they came along. They forge an unspoken yet eternal bond, entering our psyche irrevocably, and thus while we consider ourselves their custodians, they become out spiritual guardians.

In memory of Binkie, an Adorable Little Budgie Who Died

In Memory of our Dumb Friend, the Dog that God gave us, Trixie

Peter the Home Office Cat – Payment for Peter’s food was authorised by the Treasury thus, ‘I see no objection to your office keeper being allowed 1d a day from petty cash towards the maintenance of an efficient office cat.’ It seems that the money was requested not because Peter was underfed, but rather that he was overfed because of all the titbits that staff provided. It was felt that this ‘interfered with the mousing’, so if food was provided officially, the office keeper could tell staff not to give Peter any food.

In Loving memory of Our Boxers, Gremlin Gunner, Bramcote Badenia, Bramcote Blaise, Bramcote Benightful & Panfield Rhapsody

Be-Be, Our Little Dog So Loyal and True, Now He is in Peace God Bless You

In Loving Memory of our Darling Sally & Our Greyhound Swan & Our Cat Brandy Ball

In Loving Memory of Benny, a Brave Little Cat and Constant Companion to Those he Loved

Mary of Exeter, Awarded Dicken Medal for Outstanding War Service – A pigeon that made four flights carrying messages back from wartime France, returning seriously injured each time. On her last return, shrapnel damaged her neck muscles but her owner, Charlie Brewer an Exeter cobbler, made her a leather collar which held her head up and kept her going for another 10 years.

In Memory of Our Dear Pal Wolf

Mickey Callaghan, Here Lies Our Darling and You Always Will Be

In Memory of Simon, Served as ship’s cat on HMS Amethyst – Simon’s heroic ratting saving the crew from starvation during the hundred days the ship spent trapped by Communists on the Yangtze River in 1949. Simon was originally the Captain’s cat, a privileged creature who fished ice cubes out of his water jug and crunched them, but after he survived being blown up along with the Captain’s cabin, he was promoted to ‘Able Seacat’ and became pet of the whole crew. Unfortunately, the decision to bring the feline hero back to Britain proved the end of him as he caught cat flu in quarantine and died.

In Memory of Good Old Brownie

Memories of Our Faithful Doggie Pal Sally

My Babies Always In My Heart, Dede, Nicky, Sophie & Scruffy

In Memory of Rip DM, for Bravery in Locating Victims Trapped Under Blitzed Buildings – Rip was a stray who became the first search and rescue dog

In Memory of Jill who Adopted Us and Gave Us 15 Years of Loving Companionship

Shane, Bobby & Tina

In Loving Memory of Whisky, We Loved Him So, Mummy & Aunty Flo

Rusty, A Magnificent Irish Setter, We Were Better For Having Known Him, He Died with More Dignity Than That Most of Us Live – Rusty lived with Sir Bruce Forsyth in his touring caravan and performed on stage at the London Palladium. Rusty was a truly lovely fellow who performed all sorts of fantastic tricks, his favourite was to flip a biscuit off his nose and catch it in his mouth,’ recalled Sir Bruce, ‘But one day his back legs gave up on him. It was awful to witness – almost overnight he had become this pathetic, helpless animal. The only way I could take him outside for exercise was to grab hold of his tail and lift his back legs up, allowing him to walk on his front legs with his back end gliding along. This didn’t hurt him at all and he loved to be outside, but people in the street gave me filthy looks.’

In Fond Memory of Tops & Tiny Tim

In Loving Memory of Scottie Tailwaggger & Muffin

Our Buster, Faithful Intelligent Beautiful Golden Labrador

In Memory of Our Little Dog Sonny & Our Beloved Shandy, Quietly You Fell Asleep Without a Last Goodbye

In Loving Memory of Our Darling Poppet

Our Most Precious Snoopy

In Loving Memory of Perdix Crough Patrick, Bulldog

To the Dear Memory of Patch

In Loving Memory of Dinky & Dee-Dee

Beautiful Memories of Binkie, Golden Cocker Spaniel & Tender Memories of Joey, Blue Budgie

Nanoo, Sally & Rags

In Memory of Punch for Saving the Lives of Two British Officers in Israel by Attacked An Armed Terrorist

In Memory of Tiger & Rosie, Two Dear Old Strays

Peter, Loved by Everyone

Tim, Out Little Darling

Unfortunately, the Ilford Pet Cemetery is currently closed to visitors due to safety concerns after a Eucalyptus tree was brought down by the snow, but you can contribute to a fund to remove the tree and reopen the cemetery by clicking here

You may also like to read about