Bluebells At Bow Cemetery

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

With a few bluebells in flower in my garden in Spitalfields, I was inspired make a visit to Bow Cemetery and view the display of bluebells sprouting under the tall forest canopy that has grown over the graves of the numberless East Enders buried there. In each season of the the year, this hallowed ground offers me an arcadian refuge from the city streets and my spirits always lift as I pass between the ancient brick walls that enclose it, setting out to lose myself among the winding paths, lined by tombstones and overarched with trees.

Equivocal weather rendered the timing of my trip as a gamble, and I was at the mercy of chance whether I should get there and back in sunshine. Yet I tried to hedge my bets by setting out after a shower and walking quickly down the Whitechapel Rd beneath a blue sky of small fast-moving clouds – though, even as I reached Mile End, a dark thunderhead came eastwards from the City casting gloom upon the land. It was too late to retrace my steps and instead I unfurled my umbrella in the cemetery as the first raindrops fell, taking shelter under a horse chestnut, newly in leaf, as the shower became a downpour.

Standing beneath the dripping tree in the half-light of the storm, I took a survey of the wildflowers around me, primroses spangling the green, the white star-like stitchwort adorning graves, a scattering of palest pink ladies smock highlighting the ground cover, yellow celandines sharp and bright against the dark green leaves, violets and wild strawberries nestling close to the earth and may blossom and cherry blossom up above – and, of course, the bluebells’ hazy azure mist shimmering between the lines of stones tilting at irregular angles. Alone beneath the umbrella under the tree in the heart of the vast graveyard, I waited. It was the place of death, but all around me there was new growth.

Once the rain relented sufficiently for me to leave my shelter, I turned towards the entrance in acceptance that my visit was curtailed. The pungent aroma of wild garlic filled the damp air. But then – demonstrating the quick-changing weather that is characteristic of April – the clouds were gone and dazzling sunshine descended in shafts through the forest canopy turning the wet leaves into a million tiny mirrors, reflecting light in a vision of phantasmagoric luminosity. Each fresh leaf and petal and branch glowed with intense colour after the rain. I stood still and cast my eyes around to absorb every detail in this sacred place. It was a moment of recognition that has recurred throughout my life, the awe-inspiring rush of growth of plant life in England in spring.

You may also like to read about

Find out more at www.towerhamletscemetery.org

Terry Barns, Knot Tyer

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

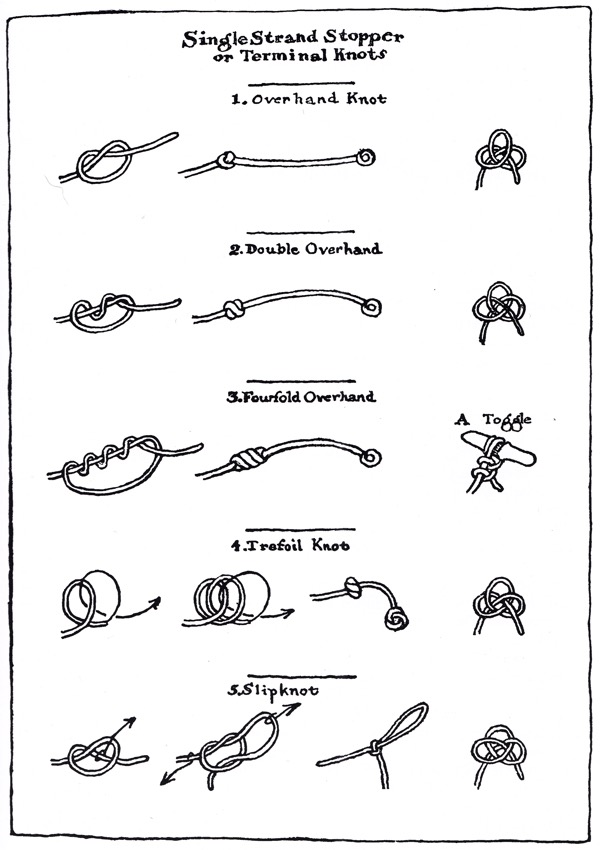

‘There isn’t really a word for it in English,’ admitted Terry Barns, ‘in French, they call it ‘matelotage’ meaning ‘sailors’ knot-making.’

Terry did not become a serious knot tyer until his fifties, yet it was a tendency that revealed itself in childhood. Celebrating the Queen’s Coronation in 1952, when Terry was just nine years old, his mother made him a guardsman’s outfit from red and black crepe paper with a busby fashioned from the shoulders cut out of an old fur coat. Terry’s contribution was to make the chin strap. ‘We got some gold string and I tied reef knots over a core, making what I now know is known as a ‘Pilgrim’s Sennet’ or a ‘Soloman’s Bar,’ he explained to me in wonder at his former precocious self, ‘but I never thought anything about it at the time.’

This is how Terry tells the story of the intervening years –

‘My early life was in the Queensbridge Rd but I was born in Hertfordshire because Hitler was trying to blow up the East End in 1944. My mum was a dress machinist and my dad was a wood machinist, he used to drill the holes in bagatelles and I still have one he made at home. In 1950, when I was six, we got a Council House in Clapton with a bathroom and an inside toilet – it was wonderful.

Somehow, I passed the 11-plus and ended up at Grocers’ Company School in Hackney Downs. When I left school at fourteen, being a prudent person, I joined the General Post Office as a telephone engineer, running around Mare St and Dalston. Nobody told me I could have stayed on at school and I soon realised that if I didn’t leave the GPO, I’d never know anything else. So I became a ‘Ten Pound Pom’ and went off to Australia in 1966.

I met my wife Carol in Pedro St in Hackney at that time and she followed me to Australia shortly after. I was a very quick learner and I had a very good job in Sydney working for a Japanese telephone company, Hitachi, but we had no intention of staying and came back in 1968. Then we got married in 1969, had three children and bought a house, so that occupied me for the next twenty years! I went back to the GPO which became BT and, when I was fifty, they asked if I would like to take some money and not go back again. So I have been living on my BT pension for the past twenty years and that has been the story of my life.’

Yet, all this time that Terry had been working with telephone cables, his tendency with string and rope had been merely in abeyance. ‘In the seventies, my wife bought me a copy of The Ashley Book of Knots,’ he revealed, bringing out a pristine hardback copy of the knotter’s bible containing nearly four thousand configurations. At a stall outside the Maritime Museum in Greenwich, Terry came across the International Guild of Knot Tyers which led to a four day course with legendary knot tyer, Des Pawson in 1994. ‘He’s got a museum of rope work in his back garden,’ Terry confided in awe.

‘I’m an engineer, but Des – he’s artistic,’ Terry informed me, ‘he educated me how to see things, he showed me when things look right.’ For over ten years, Terry has been on the Council of the Guild of Tyers, accompanying Des as his bag man, demonstrating knot work at festivals of matelotage in France – ‘My kind of holiday,’ he describes it enthusiastically.

When a sculptor cast a rope in bronze to symbolise the identity of the East End, it was Terry who wound the strands – and you can see the result at the junction of Sclater St and Bethnal Green Rd today. The largest pieces of rope you ever saw are placed as features in Terry’s front garden in Woodford. Inside the house, walls are hung with nautical paintings and shelves are lined with volumes of maritime history. They tell the story of one man’s lifetime entanglement with cable, rope and string, and remind of us of how the East End was built upon the docks, of which the ancient and ingenious culture of rope work was a major thread, still kept alive by enthusiasts like Terry Barns.

Terry with one he tied earlier

You might like to find out more at International Guild of Knot Tyers

You may also like to read about

My Pilgrimage Along The Black Path

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

‘Whan that Aprille with his shoures sote… Than longen folk to goon on pilgrimages’

Taking to heart the observation by the celebrated poet & resident of Aldgate, Geoffrey Chaucer, that April is the time for pilgrimages, I set out for day’s walk along the ancient Black Path from Walthamstow to Shoreditch. The route of this primeval footpath is still visible upon the map of the East End today, as if someone had taken a crayon and scrawled a diagonal line across the grid of the modern street plan. There is no formal map of the Black Path yet any keen walker with a sense of direction may follow it as I did.

The Black Path links with Old St in one direction and extends beyond Walthamstow in the other, tracing a trajectory between Shoreditch Church and the crossing of the River Lea at Clapton. Sometimes called the Porter’s Way, this was the route cattle were driven to Smithfield and the path used by smallholders taking produce to Spitalfields Market. Sometimes also called the Templars’ Way, it links the thirteenth century St Augustine’s Tower on land once owned by Knights Templar in Hackney with the Priory of St John in Clerkenwell where they had their headquarters.

No-one knows how old the Black Path is or why it has this name, but it once traversed open country before the roads existed. These days the path is black because it has a covering of asphalt.

I took the train from Liverpool St Station up to Walthamstow to commence my walk. In observance of custom, I commenced my pilgrimage at an inn, setting out from The Bell and following the winding road through Walthamstow to the market. A tavern by this name has stood at Bell Corner for centuries and the street that leads southwest from it, once known as Green Leaf Lane, reveals its ancient origin in its curves that trace the contours of the land.

Struggling to resist the delights of pie & mash and magnificent 99p shops, I felt like Bunyan’s pilgrim avoiding the temptations of Vanity Fair as I wandered through Walthamstow Market which extends for a mile down the High St to St James, gradually sloping away down towards the marshes. Here I turned left onto St James St itself before following Station Rd and then weaving southwest through late nineteenth century terraces, sprawling over the incline, to emerge at the level of the Walthamstow Marshes.

Then I walked along Markhouse Avenue which leads into Argall Industrial Estate, traversed by a narrow footpath enclosed with high steel fences on each side. Here you may find Allied Bakeries, Bates Laundry and evangelical churches including Deliverance Outreach Mission, Praise Harvest Community Church, Celestial Church of Christ, Mountain of Fire & Miracle Ministries and Christ United Ministries, revealing that religion may be counted as an industry in this location.

Crossing an old railway bridge and a broad tributary of the River Lea brought me onto the Leyton Marshes where I was surrounded by leaves unfurling, buds popping and blossom exploding – natural wonders that characterise the rush of spring at this sublime moment of the year. Horses graze on the marshes and the dense blackthorn hedge which lines the footpath provided a sufficiently bucolic background to evoke a sense that I was walking an ancient footpath through a rural landscape. Yet already the municipal parks department were out, unable to resist taking advantage of the sunlight to give the verges a fierce trim with their mechanical mower even before the the plants have properly sprouted.

It was a surprise to find myself amidst the busy traffic again as I crossed the Lea Bridge and found myself back in the East End, of which the River Lea is its eastern boundary. The position of this crossing – once a ford, then a ferry and finally a bridge – defines the route of the Black Path, tracing a line due southwest from here.

I followed the diagonal path bisecting the well-kept lawn of Millfields and walked up Powerscroft Rd to arrive in the heart of Hackney at St Augustine’s Tower, built in 1292 and a major landmark upon my route. Yet I did not want to absorb the chaos of this crossroads where so many routes meet at the top of Mare St, instead I walked quickly past the Town Hall and picked up the quiet footpath next to the museum known as Hackney Grove. This byway has always fascinated me, leading under the railway line to emerge onto London Fields.

The drovers once could graze their cattle, sheep and geese overnight on this common land before setting off at dawn for Smithfield Market, a practice recalled today in the names of Sheep Lane and the Cat & Mutton pub. The curve of Broadway Market leading through Goldsmith’s Row down to Columbia Rd reveals its origin as a cattle track. From the west end of Columbia Rd, it was a short walk along Virginia Rd on the northern side of the Boundary Estate to arrive at my destination, Shoreditch Church.

If I chose to follow ancient pathways further, I could have walked west along Old St towards Bath, north up the Kingsland Rd to York, east along the Roman Rd towards Colchester or south down Bishopsgate to the City of London. But flushed and footweary after my six mile hike, I was grateful to return home to Spitalfields and put my feet up in the shade of the house. For millennia, when it was the sole route, countless numbers travelled along the old Black Path from Walthamstow to Shoreditch, but on that day there was just me on my solitary pilgrimage.

At Bell Corner, Walthamstow

‘Fellowship is Life’

Two quinces for £1.50 in Walthamstow Market

Walthamstow Market is a mile long

‘struggling to resist the delights of pie & mash’

At St James St

Station Rd

‘leaves unfurling, buds popping and blossom exploding which characterise the rush of spring’

Enclosed path through Argall Industrial Estate skirting Allied Bakeries

Argall Avenue

‘These days the path is black because it has a covering of asphalt’

Railway bridge leading to the Leyton marshes

A tributary of the River Lea

Horses graze on the Leyton marshes

“dense blackthorn which line the footpath provided a sufficiently bucolic background to evoke a sense that I was walking an ancient footpath”

‘the municipal parks department were out, unable to resist taking advantage of the sunlight to give the verges a fierce trim with their mechanical mower even before the the plants have properly sprouted’

The River Lea is the eastern boundary of the East End

Across Millfields Park towards Powerscroft Rd

Thirteenth century St Augustine’s Tower in Hackney

Worn steps in Hackney Grove

In London Fields

At Cat & Mutton Bridge, Broadway Market

Columbia Rd

St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch

You may also like to read about

Cruikshank’s London Almanack, 1835

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

In 1835, George Cruikshank drew these illustrations of the notable seasons and festivals of the year in London for The Comic Almanack published by Charles Tilt of Fleet St. Produced from 1835 – 53, distinguished literary contributors included William Makepeace Thackeray and Henry Mayhew, but I especially enjoy George Cruikshank’s drawings for their detailed observation of the teeming street life of the capital. (Click on any of these images to enlarge)

JANUARY – Everybody freezes

FEBRUARY – Valentine’s Day

MARCH – March winds

APRIL – April showers

MAY – Sweeps on May Day

JUNE – At the Royal Academy

JULY – At Vauxhall Gardens

AUGUST – Oyster day

SEPTEMBER – Bartholomew Fair

OCTOBER – Return to Town

NOVEMBER – Penny for the Guy

DECEMBER – Christmas

You may also enjoy

George Cruikshank’s Comic Alphabet

At The Monument

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

Novelist Kate Griffin describes her first visit to The Monument

If you lay The Monument on its side to the West, the flame hits the spot in Pudding Lane where the fire broke out in Mr Farriner’s bakery during the early hours of 2nd September, 1666.

One of my earliest London memories is climbing to the top of The Monument with my dad when I was around four years old. I remember clearly pushing through the turnstile and dodging through people’s legs to reach the enticing black marble staircase that spiralled up through the centre of the column.

I could not wait to get to the top and see the view. Once we were up there and my dad lifted me onto his shoulders – so that I was even higher than everyone around us on the narrow stone platform – the thrill was electrifying. Yet I doubt ‘Health & Safety’ would allow that these days, even though the top of The Monument is now securely caged as a protection against pigeons, and a deterrent to potential suicides. (There were a few of those in the past.)

When I was four, I raced up those three hundred and eleven stairs but returning – in the company of ohotographer Alex Pink – over half a century later, I make the ascent at a much more leisurely pace. In fact, I stop several times and lean against the curved wall of cool Portland stone. Ostensibly, this is to allow an excited party of school children to pass as they loop back down the narrow stairs but, actually, I pause because the muscles in my legs are crying out for mercy and I am beginning to wonder if there could be an oxygen cylinder around the next turn of the stair.

Guide Mandy Thurkle grins as I gasp for breath. “You could say it keeps us fit. There are always two of us here on duty and, between us, we have to go up four times a day to make our regular checks. They say the calories you’ve burned off when you reach the top is the equivalent of a Mars Bar – not that I’m tempted. I’m not that keen on them.” She stands aside in the narrow entrance through the plinth as another party of school children jostles into the little atrium at the foot of the stairwell. There is an ‘ooh’ of excitement as they cluster together and crane their necks to look up at the stone steps coiling above them. “I love working here,” Mandy says, “I love the interaction with the visitors, seeing their reactions and answering their questions – the children’s are usually the best.”

Built to commemorate the rebuilding of the City after the Great Fire of London in 1666, The Monument – still the tallest isolated stone column in the world – attracts more than 220,000 visitors a year. Designed by Robert Hooke under the supervision of Christopher Wren, it was one of the first visitor attractions in London to admit paying entrants. Back in the eighteenth century, early wardens and their families actually lived in the cell-like basement beneath the massive plinth. This room was originally designed to house Hooke’s astronomical observatory – he dreamed of using the new building as a giant telescope while Wren saw it as a useful place to conduct his gravity experiments.

It is easy to imagine those first wardens welcoming a succession of bewigged and patch-faced sightseers eager to view the newly-rising city from the finest vantage point. Once, The Monument was a towering landmark, clearly visible from any angle in the City, now that it is confined by ugly, boxy offices, its former significance is obscured by walls of glass and concrete. In any other great European capital, the little piazza in which it stands would become a destination in itself, flanked by coffee shops or smart boutiques, but these days you come upon this extraordinary building almost accidentally.

French-born Nathalie Rebillon-Lopez, Monument Assistant Exhibition Manager, agrees, “In France, I worked for the equivalent of English Heritage and they would never have allowed a building like this to be hemmed in. There is a rule that development cannot take place within fifty metres of an important site.” She shrugs, “But then, Paris is sometimes like a giant museum. You have to move with the times and things have to change. I often think London is good at that – it is very open to creativity and eclecticism, it is always alive.”

Of course, Nathalie is right but as we speak in the little paved square it is hard not to feel oppressed by the sheer scale of the new ‘Walkie Talkie’ building lumbering ever upwards in the streets beyond. Where The Monument is all about elegant neo-classical balance, the ‘Walkie Talkie’ is a cumbersome affront to the skyline – a visual joke that is not very funny. Monument guide Mandy, who has worked at the building and at its sister attraction Tower Bridge for twenty-three years, shares my misgivings. “I get a little bit upset at the top sometimes,” she confides, “I look down and see all the tiny old churches and their spires completely lost amongst the new buildings and it seems wrong.”

Not surprisingly, given that the Great Fire of London is a component of Key Stage One on the national curriculum, many of The Monument’s visitors today are under ten-years-old. They all receive a certificate on leaving to prove that they have been to the top. “Usually they are very well behaved,” says Nathalie approvingly,“We have to monitor stickers on the walls and things like chewing gum and even the odd bit of graffiti, but generally with those unwelcome additions, adults are more likely to be the offenders!”

The interior of The Monument – all two hundred and two feet of it – is cleaned by a team of regulars who come in three times a week at night when the visitors are gone. They must be the fittest cleaning crew in London! “They use simple mops and buckets to clean the marble stairs from top to bottom,” Nathalie explains, “We have to treat the building very, very gently because it is Grade One listed. We cannot make any changes or alterations without consulting English Heritage – even our turnstile, which we no longer use, is listed.”

When I first visited The Monument back in the sixties, it was black with soot and pollution. Today, after the major conservation work, the creamy Portland stone gleams almost as brightly as the gilded flame at the very top.

“We welcome visitors from all over the world and a surprising number of Londoners come here too,” says Nathalie, “It’s important to people – it’s part of the fabric of the city. It has a good feeling and it’s a very romantic place. For a fee, we allow people to come here after hours and propose with the whole of London spread out below them. Imagine that!” Standing on the viewing platform at the very top of the column, it is not hard to see why that would be appealing. Despite the development taking place in every direction, the view is simply breathtaking. Here at the very heart of old London you can look down on the streets below and still see, quite clearly, the imprint of the ancient, incinerated city that The Monument was built to commemorate.

Once I manage to catch my breath, I ask if people ever give up before they reach the top and the spectacular view. Nathalie laughs, “That’s quite rare. Once they’ve started most people are very determined. Just occasionally we might have a visitor who can’t make it because of vertigo, but we always give them a refund.”

For my money, whether you are a tourist or native, the best three pounds you could possibly spend in the City of London is the the entry fee to The Monument.

“my legs are crying out for mercy”

The view from the top photographed by Alex Pink

The view from the top photographed fifty years ago by Roland Collins

The Monument seen from Billingsgate.

In Pudding Lane

Mandy Thurkle –“You could say it keeps us fit. There are always two of us here on duty and, between us, we have to go up four times a day to make our regular checks.”

Sean Thompson-Patterson, first day of work at The Monument.

The reclining woman on the left is the City ‘injured by fire.’ The beehive at her feet represents the industry that will help to rebuild the City. The winged creature behind her is Time which will help the City to regain her feet again. Charles II stands on the right in a Roman breastplate, putting things to rights. At his feet Envy is disappearing into a hole, while Peace and Plenty float on a cloud above the scene.

Photographs copyright © Alex Pink

The Monument, Fish St Hill, EC3R 6DB . Open daily. Summer (April – September) 9:30am – 6pm. Winter (October -March) 9:30am – 5:30pm.

The Highdays & Holidays Of Old London

Join me for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF THE CITY OF LONDON this afternoon Easter Monday 1st April at 2pm or Sunday 21st April

CLICK HERE TO BOOK

On Easter Monday, let us to consider the highdays & holidays of old London

Boys lining up at The Oval, c.1930

School is out. Work is out. All of London is on the lam. Everyone is on the streets. Everyone is in the parks. What is going on? Is it a jamboree? Is it a wingding? Is it a shindig? Is it a bevy? Is it a bash?

These are the high days and holidays of old London, as recorded on glass slides by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society and once used for magic lantern shows at the Bishopsgate Institute.

No doubt these lectures had an educational purpose, elucidating the remote origins of London’s quaint old ceremonies. No doubt they had a patriotic purpose to encourage wonder and sentiment at the marvel of royal pageantry. Yet the simple truth is that Londoners – in common with the rest of humanity – are always eager for novelty, entertainment and spectacle, always seeking any excuse to have fun. And London is a city ripe with all kinds of opportunities for amusement, as illustrated by these magnificent photographs of its citizens at play.

Are you ready? Are you togged up? Did you brush your hair? Did you polish your shoes? There is no time to lose. We need the make the most of our high days and holidays. And we need to get there before the parade passes by.

At Hampstead Heath, c.1910.

Walls Ice Cream vendor, c.1920.

At Hampstead Heath, c.1910.

At Hampstead Heath, c.1910.

Balloon ascent at Crystal Palace, Sydenham, c.1930.

At the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens, 1896.

Christ’s Hospital Procession across bridge on St Matthews Day, 1936.

A cycle excursion to The Spotted Dog in West Ham, 1930.

Pancake Greaze at Westminster School on Shrove Tuesday, c.1910.

Variety at the Shepherds Bush Empire, c.1920.

Dignitaries visit the Chelsea Royal Hospital, c.1920.

Games at the Foundling Hospital, Bloomsbury, c.1920.

Riders in Rotten Row, Hyde Park, c.1910.

Physiotherapy at a Sanatorium, 1916.

Vintners’ Company, Master’s Installation procession, City of London, c.1920.

Boating on the lake in Battersea Park, c.1920.

The King’s Coach, c.1911.

Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession, 1897.

Lord Mayor’s Procession passing St Paul’s, 1933.

Policemen gives directions to ladies at the coronation of Edward VII, 1902.

After the procession for the coronation of George V, c.1911.

Observance of the feast of Charles I at Church of St. Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe, 1932.

Chief Yeoman Warder oversees the Beating of the Bounds at the Tower of London, 1920.

Schoolchildren Beating the Bounds at the Tower of London, 1920.

A cycle excursion to Chingford Old Church, c.1910.

Litterbugs at Hampstead Heath, c.1930.

The Foundling Hospital Anti-Litter Band, c.1930.

Distribution of sixpences to widows at St Bartholomew the Great on Good Friday, c.1920.

Visiting the Cast Court to see Trajan’s Column at the Victoria & Albert Museum, c.1920.

A trip from Chelsea Pier, c.1910.

Doggett’s Coat & Badge Race, c.1920.

Feeding pigeons outside St Paul’s, c.1910.

Building the Great Wheel, Earls Court, c.1910.

Glass slides copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

My Scrap Collection

Join me for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF THE CITY OF LONDON on Easter Monday 1st April at 2pm

CLICK HERE TO BOOK

For some years, I have been collecting Victorian scraps of tradesmen and street characters, and putting them in a drawer. The Easter holidays gives me the ideal opportunity to search through the contents and study my collection in detail. I am especially fascinated by the mixture of whimsical fantasy and social observation in these colourful miniatures, in which even the comic grotesques are derived from the daily reality of the collectors who once cherished these images.

Street Photographer

Exotic Birds

Sweets & Dainties

Acrobat & Performing Dog

Performing Dogs

The Muffin Man

Street Musician

Street Musician

Baker

Smoker

Butcher

Waiter

Itinerant

Sweep

Naturalist

Lounge Lizard

Dustman

Costermonger

Spraying the roads

Milkman

Knife Grinder

Scottish Herring Girls followed the shoals around the East Coast, gutting and packing the herring.

You may like to see these other scraps from my collection