The Hackney Yearbook

Behold the wonders of commerce and retail over a century ago, courtesy of the Hackney Year Book 1906 from the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute!

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Adverts from Shoreditch Borough Guide

An Important Correction

The email address we published yesterday for you to write to the Secretary of State asking him to call in the Whitechapel Bell Foundry was incorrect.

You email you need to use is PCU@communities.gsi.gov.uk

If you wrote to the wrong address, please resend it to the email above.

We apologise for any confusion, and thank you for your patience and support.

Note that the incorrect email which we published yesterday in good faith was accurately quoted from ‘House of Commons Briefing Paper Number 00930, 31st January 2019, Calling-in planning applications (England).’

Read the full instructions here

Peri Parkes’ Conder St Paintings

Fiona Atkins who curated the current exhibition at Townhouse Spitalfields considers the first pictures Peri Parkes painted while living in Conder St, Stepney. In these works, he evolved subtly from the academic style of the Slade towards a recognition of the presence of people in the East End.

These paintings and more are on display until Sunday 8th December in ‘Peri Parkes, The Last View.’

Conder St 1, 1979

The years after Peri Parkes left the Slade were turbulent ones for him. He had married while he was there and they had the first of his two daughters shortly after, but by 1979 he and his wife had divorced and he moved in with his artist friend Martin Ives, who was living in a prefab run by Acme Housing Association on Conder St, off Salmon Lane in Stepney.

In the seventies, artists were at college for four or five years but were given no practical advice on how to survive or make a living in the world. Afterwards, they were faced with the prospect of finding a studio, buying materials and equipment and then, unable to make a living as artists, finding a job to pay for it. Inevitably, artists cut costs to reduce the amount of time spent working and devote as much time as possible to their art.

Acme Housing Association was started in 1972 to provide studio and living space for artists, by working with the Greater London Council and taking derelict properties for low rents. The GLC had thousands of such properties on its hands, bought by compulsory purchase as part of plans for post-war redevelopment before the money ran out in the economic downturn of the seventies.

Thus Peri Parkes lived at 9 Conder St in the late seventies and early eighties while working as an art teacher locally. His paintings show the influence of William Coldstream who had been Head of the Slade. During Peri’s time there, Coldstream had started to paint a series of views of Westminster from the seventeenth floor of the Department of the Environment. Although probably not originally conceived as a series, his biographer Bruce Laughton says he kept seeing new configurations each time he finished one. This may also be true of Peri’s paintings of the backs of houses in Conder St. They reveal the same desire to show new configurations, which can be used to put most of this series of paintings in order.

The painting above appears to be the first of the Conder St series of paintings of backs of houses and was probably painted shortly after Peri arrived in the East End in 1979. It has a tight, linear structure, the bricks in the walls at the front are all carefully delineated and Coldstream-style ‘dots and dashes’ for measurements are visible. The paint is applied in broad washes of colour, particularly on the backs of the houses themselves, which gives a luminous glow to the colour.

By the second Conder St painting below, Peri’s style is looser. The tree reflected in the window is painted more freely, the bricks are indicated rather than painted individually and the colour is no longer applied in expanses of colour. The angle of the painting is different too and Peri’s gaze is more focused on the foreground and the collection of a picket fence, a compost bin and a washing line.

The third painting of Conder St was titled ‘House in the East’ at the Tolly Cobbold Eastern Arts exhibition. The focus in this picture is on the same view as the previous painting but with the addition of foliage.

Peri Parkes wrote a statement in the catalogue: ‘This was painted in the space of a year. I hope something of the building’s organic structure (moisture, decomposition) has registered in the painting. At the very beginning, a rich snakeskin pattern of moss down a wall was the painting’s main focal point. One day it was scraped away. Nonetheless, I have determined that its absence remains the main focus of the painting.’

It is curious that, although for Peri the absence of the moss was the focus, it is not depicted in the finished painting. He had written in an essay for his teacher’s training: ‘By imagination I do not mean the ability to invent, but to inhabit, to find oneself in everything.’

This painting illustrates Peri’s desire to ‘inhabit’ his paintings and paint as though ‘touching the surface,’ in order that his brushstrokes reflected what he knew had once been there, so his sensation of it would inhabit the painting. This notion came from Peri’s teacher at the Slade, Patrick George, who had been at Camberwell College of Art after the war with William Coldstream. His paintings are a search for the essence of his subject rather than a literal representation. Patrick George was one of the curators of the Tolly Cobbold exhibition for which this painting was selected in 1981, Peri’s first recorded exhibited work.

The similarity in Peri’s style, palette and treatment of the foliage suggests that the fourth Conder St painting was done at the same time as ‘House in the East.’ Ten years later, Peri successfully submitted it for exhibition in the RA Summer Show of 1995, suggesting that this was a painting which continued to satisfy him.

The fifth Conder St picture represents a complete change of approach: an exploration of the visual logic of the relationship between the lines and the structure holding it all together, which renders the painting almost abstract in places. Interestingly though, there is the suggestion of two figures, the first in Peri’s work. They are faceless and probably hanging out washing – representing a virtual constant of life rather than any individual – but something so frequently observed it became a fundamental part of his world in the East End.

Conder St 2, c.1980

Conder St 3, House in the East, c. 1980-1

Conder St 4, c.1982

Conder St 5, c.1982 – in this painting, figures appear for the first time

Conder St 6, c. 1981-2

Conder St 7, c. 1981-2

Paintings copyright © Estate of Peri Parkes

You may also like to read about

A Letter To The Secretary Of State

Casting a bell at Whitechapel Bell Foundry in July 1933

We were appalled by the disgraceful decision of Tower Hamlets Council in November to grant permission for change of use from bell foundry to boutique hotel. This destroys any future for the Whitechapel Bell Foundry as a working foundry, reducing centuries of our history to a side-show for tourists in a quirky bell-themed hotel.

It is imperative now that the Secretary of State call in this planning application, taking it out of the hands of Tower Hamlets Council and holding a Public Inquiry. Last month’s farcical planning meeting revealed that the national and international significance of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry render it too important for its fate to be decided by the local authority.

With the forthcoming General Election imminent, we have to move very fast. We need as many people as possible to write to Secretary of State immediately. Use your own words and give your personal opinions but be sure to include the key points listed here. Read the guidance below and write today, then forward this to your friends and family, encouraging them to do the same.

HOW TO WRITE EFFECTIVELY TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE

- Address your letter to Robert Jenrick, Secretary of State for Housing, Communities & Local Government.

- Ask the Secretary of State to issue a ‘holding direction’ which means that planning permission cannot proceed.

- Ask the Secretary of State to call in the planning application for the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and hold a Public Inquiry.

- Point out that the hotel planning application causes ‘substantial harm’ to a very important heritage asset.

- Emphasise the significance of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and the very controversial nature of this proposal, locally, nationally and internationally.

Anyone can write, wherever you are in the world, but be sure to include your postal address and send your letter by email to

PCU@communities.gsi.gov.uk

or by post to

National Planning Casework Unit

5 St Philips Place

Colmore Row

Birmingham BP3 2PW

The Bell of Hope in Manhattan was cast at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and presented by the Lord Mayor of London to the people of New York on the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks

You may also like to read about

The Fate of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Nigel Taylor, Tower Bell Manager

Four Hundred Years at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Pearl Binder at Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Dorothy Rendell at Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Hope for The Whitechapel Bell Foundry

A Petition to Save the Bell Foundry

Save the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

So Long, Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Fourteen Short Poems About The Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Authors At The Bloomsbury Jamboree

In collaboration with Tim Mainstone of Mainstone Press and Joe Pearson of Design for Today, I am organising a BLOOMSBURY JAMBOREE, a festival of books and print, illustration, talks and merriment on SUNDAY 8th DECEMBER from 11am until 5pm at the ART WORKERS GUILD, 6 Queens Sq, WC1.

Meet the authors and artists who will be speaking and signing copies of their books.

We advise readers to come early to avoid the rush…

Photo by George Woodford

Julian Woodford will be signing THE BOSS OF BETHNAL GREEN at 1pm

Photo by Patricia Niven

Click here for a talk on MEMOIRS OF A COCKNEY SIKH by Suresh Singh at 1pm

Photo by Colin O’Brien

Click here for a talk on SHOPFRONTS OF LONDON by Eleanor Crow at 2pm

Photo by The Gentle Author

Click here for a talk on MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND by Adam Dant at 3pm

Photo by Stuart Freedman

Doreen Fletcher will be signing copies of her monograph at 3pm

Click here for a talk on GHASTLY FACADISM in London by The Gentle Author at 3pm

The Gentle Author will be signing books at 4pm

William Marshall Craig’s Itinerant Traders

A personal favourite among the innumerable prints of the “Cries of London” published over the centuries is William Marshall Craig’s Itinerant Traders of London in their Ordinary Costume with Notices of Remarkable Places given in the Background from 1804. A portrait artist who exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1788 and 1827, Craig was appointed painter in watercolours to the queen. This set of prints was discovered at the Bishopsgate Institute, bound into the back of a larger volume of “Modern London” published in 1805, and the vibrancy of their pristine colours suggests they have never been exposed to daylight in two centuries.

Hair brooms, hearth brooms, brushes, sieves, bowls, clothes horses and lines and and almost every article of turnery, are cried in the streets. Some of these walking turners travel with a cart, by which they can extend their trade and their profit, but the greater number carry the shop on their shoulders, and find customers sufficient to afford them a decent subsistence, the profit on turnery being considerable and the consumption certain. (Shoreditch Church, standing at the northern extremity of Holywell St, commonly called Shoreditch, is a church of peculiar beauty. It has a portico in front, elevated upon a flight of steps and enclosed with an iron railing, which is disgraced by a plantation of poplar trees.)

Baking & boiling apples are cried in the streets of the metropolis from their earliest appearance in sumer throughout the whole winter. Prodigious quantities of apples are brought to the London markets, where they are sold by the hundred to the criers, who retail them about the streets in pennyworths, or at so much per dozen according to their quality. In winter, the barrow woman usually stations herself at the corner of a street, and is supplied with a pan of lighted charcoal, over which, on a plate of tin, she roasts a part of her stock, and disposes of her hot apples to the labouring men and shivering boys who pass her barrow. (At Stratford Place, on the north side of Oxford St.)

Band boxes. Generally made of pasteboard, and neatly covered with coloured papers, are of all sizes, and sold at every intermediate price between sixpence and three shillings. Some made of slight deal, covered like the others, but in addition to their greater strength having a lock and key, sell according to their size, from three shillings and sixpence to six shillings each. The crier of band boxes or his family manufacture them, and these cheap articles of convenience are only to be bought of the persons who cry them through the streets. (Bibliotheque d’Education or Tabart’s Juvenile Library is in New Bond St.)

Baskets. Market, fruit, bread, bird, work and many other kinds of baskets, the inferior rush, the better sort of osier, and some of them neatly coloured and adorned, are to be bought cheaply of the criers of baskets. (Whitfield’s Tabernacle, north of Finsbury Sq, is a large octagon building, the place of worship belonging to the Calvinistic methodists.)

Bellows to mend. The bellows mender carries his tools and apparatus buckled in a leather bag to his back, and, like the chair mender, exercises his occupation in any convenient corner of the street. The bellows mender sometimes professes the trade of the tinker. (Smithfield where the great cattle market of London is held, on which days it is disagreeable, if not dangerous to pass in the early part of the day on account of the oxen passing from the market, on whom the drovers sometimes exercise great cruelty.)

Brick Dust is carried about the metropolis in small sacks on the backs of asses, and is sold at one penny a quart. As brick dust is scarcely used in London for any other purpose than that of knife cleaning, the criers are not numerous, but they are remarkable for their fondness and their training of bull dogs. This prediliction they have in common with the lamp lighters of the metropolis. (Portman Sq stands in Marylebone. In the middle is an oval enclosure which is ornamented with clumps of trees, flowering shrubs and evergreens.)

Buy a bill of the play. The doors of the London theatres are surrounded each night, as soon as they open, with the criers of playbills. These are mostly women, who also carry baskets of fruit. The titles of the play and entertainment, and the name and character of every performer for the night, are found in the bills, which are printed at the expense of the theatre, and are sold by the hundred to the criers, who retail them at one penny a bill, unless fruit is bought, when with the sale of half a dozen oranges, they will present their customer a bill of the play gratis. (Drury Lane Theatre, part of the colonnade fronting to Russell St, Covent Garden.)

Cats’ & dogs’ meat, consisting of horse flesh, bullocks’ livers and tripe cuttings is carried to every part of the town. The two former are sold by weight at twopence per pound and the latter tied up in bunches of one penny each. Although this is the most disagreeable and offensive commodity cried for sale in London, the occupation seems to be engrossed by women. It frequently happens in the streets frequented by carriages that, as soon as one of these purveyors for cats and dogs arrives, she is surrounded by a crowd of animals, and were she not as severe as vigilant, could scarcely avoid the depredations of her hungry followers. (Bethlem Hospital stands on the south side of Moorfields. On each side of the iron gate is a figure, one of melancholy and the other of raging madness.)

Chairs to mend. The business of mending chairs is generally conducted by a family or a partnership. One carries the bundle of rush and collects old chairs, while the workman seating himself in some convenient corner on the pavement, exercises his trade. For small repairs they charge from fourpence to one shilling, and for newly covering a chair from eighteen pence to half a crown, according to the fineness of the rush required and the neatness of the workmanship. It is necessary to bargain for price prior to the delivery of the chairs, or the chair mender will not fail to demand an exorbitant compensation for his time and labour. (Soho Sq, a square enclosure with shrubbery at the centre, begun in the time of Charles II.)

Cherries appear in London markets early in June, and shortly afterwards become sufficiently abundant to be cried by the barrow women in the streets at sixpence, fourpence, and sometimes as low as threepence per pound. The May Duke and the White and Black Heart are succeeded by the Kentish Cherry which is more plentiful and cheaper than the former kinds and consequently most offered in the streets. Next follows the small black cherry called the Blackaroon, which is also a profitable commodity for the barrows. The barrow women undersell the shops by twopence or threepence per pound but their weights are generally to be questioned, and this is so notorious an objection that they universally add “full weight” to the cry of “cherries!” (Entrance to St James’ Palace, its external appearance does not convey any idea of its magnificence.)

Doormats, of all kinds, rush and rope, from sixpence to four shillings each, with table mats of various sorts are daily cried through the streets of London. (The equestrian statue in brass of Charles II in Whitehall, cast in 1635 by Grinling Gibbons, was erected upon its present pedestal in 1678)

Dust O! One of the most useful, among the numberless regulations that promote the cleanliness and comfort of the inhabitants of London, is that which relieves them from the encumbrance of their dust and ashes. Dust carts ply the streets through the morning in every part of the metropolis. Two men go with each cart, ringing a large bell and calling “Dust O!” Daily, they empty the dust bins of all the refuse that is thrown into them. The ashes are sold for manure, the cinders for fuel and the bones to the burning houses. (New Church in the Strand, contiguous to Somerset House and dividing the very street in two.)

Green Hastens! The earliest pea brought to the London market is distinguished by the name of “Hastens,” it belongs to the dwarf genus and is succeeded by the Hotspur. This early pea, the real Hastens, is raised in hotbeds and sold in the markets at the high price of a guinea per quart. The name of Hastens is however indiscriminately used by all the vendors to all the peas, and the cry of “Green Hastens!” resounds through every street and alley of London to the very latest crop of the season. Peas become plentiful and cheap in June, and are retailed from carts in the streets at tenpence, eightpence, and sixpence per peck. (Newgate, on the north side of Ludgate Hill is built entirely of stone.)

Hot loaves, for the breakfast and tea table, are cried at the hours of eight and nine in the morning, and from four to six in the afternoon, during the summer months. These loaves are made of the whitest flour and sold at one and two a penny. In winter, the crier of hot loaves substitutes muffins and crumpets, carrying them in the same manner, and in both instances carrying a little bell as he passes through the streets. (St Martin in the Fields, the design of this portico was taken from an ancient temple at Nismes in France and is particularly grand and beautiful.)

Hot Spiced Gingerbread, sold in oblong flat cakes of one halfpenny each, very well made, well baked and kept extremely hot is a very pleasing regale to the pedestrians of London in cold and gloomy evenings. This cheap luxury is only to be obtained in winter, and when that dreary season is supplanted by the long light days of summer, the well-known retailer of Hot Spiced Gingerbread, portrayed in the plate, takes his stand near the portico of the Pantheon, with a basket of Banbury and other cakes. (The Pantheon stands on Oxford St, originally designed for concerts, it is only used for masquerades in the winter season.)

A Showman – This amusing personage generally draws a crowd about him in whatever street he fixes his moveable pantomime, as the children who cannot afford the penny or halfpenny insight into the show box are yet greatly entertained with his descriptive harangues and the perpetual climbing of the squirrels in the round wire cage above the box, by whose incessant motion the row of bells on the top are constantly rung. The show consists of a series of coloured pictures which the spectator views through a magnifying glass while the exhibitor rehearses the history and shifts the scenes by the aid of strings. (Hyde Park Corner, this entrance to London is worthy of the grandeur and extent of the metropolis. On one side of the spacious street of Piccadilly are lofty and elegant houses and on the other is a fine view of Green Park and Westminster Abbey.)

Mackerel – More plentiful than any other fish in London, they are brought from the western coast and afford a livelihood to numbers of men and women who cry them through the streets every day in the week, not excepting Sunday. Mackerel boats being allowed by act of Parliament to dispose of their perishable cargo on Sunday morning, prior to the commencement of divine service. No other fish partake that privilege. (Billingsgate Market commences at three o’clock in the morning in summer and four in winter. Salesmen receive the cargo from the boats and announce by a crier of what kinds they consist. These salesmen have a great commission and generally make fortunes.)

Rhubarb! – The Turk, whose portrait is accurately given in this plate, has sold Rhubarb in the streets of the metropolis during many years. He constantly appears in his turban, trousers and mustachios and deals in no other article. As his drug has been found to be of the most genuine quality, the sale affords him a comfortable livelihood. (Russell Sq is one of the largest in London, broad streets intersect at its corners and in the middle, which add to its beauty and remove the general objection to squares by ventilating the air.)

Milk below! – Every day of the year, both morning and afternoon, milk is carried through each square, each street and alley of the metropolis in tin pails, suspended from a yoke placed on the shoulders of the crier. Milk is sold at fourpence per quart or fivepence for the better sort, yet the advance of price does not ensure its purity for it is generally mixed in a great proportion with water by the retailers before they leave the milk houses. The adulteration of the milk added to the wholesale cost leaves an average profit of cent per cent to the vendors of this useful article. Few retail traders are exercised with equal gain. (Cavendish Sq is in Marylebone. In the centre of the enclosure, erected on a lofty pedestal is a bronze statue of William Duke of Cumberland, all very richly gilded and burnished. In the background are two very elegant houses built by Mr Tufnell.)

Matches – The criers are very numerous and among the poorest inhabitants, subsisting more on the waste meats they receive from the kitchens where they sell their matches at six bunches per penny, than on the profits arising from their sale. Old women, crippled men, or a mother followed by three or four ragged children, and offering their matches for sale are often relieved when the importunity of the mere beggar is rejected. The elder child of a poor family, like the boy seen in the plate, are frequent traders in matches and generally sing a kind of song, and sell and beg alternately. (The Mansion House is a stone building of considerable magnitude standing at the west end of Cornhill, the residence of the Lord Mayor of London. Lord Burlington sent down an original design worthy of Palladio, but this was rejected and the plan of a freeman of the City adopted in its place. The man was originally a shipwright and the front of his Mansion House has all the resemblance possible to a deep-laden Indiaman.)

Strawberries – Brought fresh gathered to the markets in the height of their season, both morning and afternoon, they are sold in pottles containing something less than a quart each. The crier adds one penny to the price of the strawberries for the pottle which if returned by her customer, she abates. Great numbers of men and women are employed in crying strawberries during their season through the streets of London at sixpence per pottle. ( Covent Garden Market is entirely appropriated to fruit & vegetables. In the south side is a range of shops which contain the choicest produce and the most expensive productions of the hot house. The centre of the market, as shown in the plate, although less pleasing to the eye is more inviting to the general class of buyers.)

A Poor Sweep Sir! – In all the thoroughfares of the metropolis, boys and women employ themselves in dirty weather in sweeping crossings. The foot passenger is constantly importuned and frequently rewards the poor sweep with a halfpenny, which indeed he sometimes deserves for in the winter after fall of snow if a thaw should come before the scavengers have had time to remove it, many streets cannot be crossed without being up to the middle of the leg in dirt. Many of these sweepers who choose their station with judgement reap a plentiful harvest from their labours. (Blackfriars Bridge crosses the river from Bridge St to Surrey St where this view is taken. The width and loftiness of the arches and the whole light construction of this bridge is uncommonly pleasing to the eye and St Paul’s cathedral displays much of the grandeur of its extensive outline when viewed from Blackfriars Bridge.)

Knives to grind! – The apparatus of a knife grinder is accurately delineated in this plate. The same wheel turns his grinding and his whetting stone. On a smaller wheel, projecting beyond the other he trundles his commodious shop from street to street. He charges for grinding and setting scissors one penny or twopence per pair, for penknives one penny each and table knives one shilling and sixpence per dozen, according to the polish that is required. (Whitehall – this beautiful structure stands in Parliament St, begun in 1619 from a design by Inigo Jones in his purest manner and cost £17,000. The northern end of the palace, to the left of the plate, is that through which King Charles stepped onto the scaffold.)

Lavender – “Six bunches a penny, sweet lavender!” is the cry that invites in the street the purchasers of this cheap and pleasant perfume. A considerable quantity of the shrub is sold to the middling-classes of the inhabitants, who are fond of placing lavender among their linen – the scent of which conquers that of the soap used in washing. (Temple Bar was erected to divide the strand from Fleet St in 1670 after the Great Fire. On the top of this gate were exhibited the heads of the unfortunate victims to the justice of their country for the crime of high treason. The last sad mementos of this kind were the rebels of 1746.)

Sweep Soot O! – The occupation of chimney sweep begins with break of day. A master sweep patrols the street for custom attended by two or three boys, the taller ones carrying the bag of soot, and directing the diminutive creature who, stripped perfectly naked, ascends and cleans the chimney. The greatest profit arises from the sake of soot which is used for manure. The hard condition of the sweep devolves upon the smallest and feeblest of the children apprenticed from the parish workhouse. (Foundling Hospital, a handsome and commodious building in Guildford St, stands at the upper end of a large piece of ground in which the children of the foundation are allowed to play in fine weather.)

Sand O! – Sand is an article of general use in London, principally for cleaning kitchen utensils. Its greatest consumption is in the outskirts of the metropolis where the cleanly housewife strews sand plentifully over the floor to guard her newly scoured boards from dirty footsteps, a carpet of small expense and easy to be renewed. Sand is sold by measure, red sand twopence halfpenny and white five farthings per peck. (St Giles’ Church at the west end of Broad St Giles is a very handsome structure. Over the gate, entering the church yard is fixed a curious bass-relief representing the Last Judgement and containing a very great number of figures, set up in the 1686)

New potatoes – About the latter end of June and July, they become sufficiently plentiful to be cried at a tolerable rate in the streets. They are sold wholesale in markets by the bushel and retail by the pound. Three halfpence or a penny per pound is the average price from a barrow. (Middlesex Hospital at the northern end of Berners St is the county hospital for diseased persons. It stands in a large court with trees, covered by a wall in front with two gates, one of which is represented in the plate.)

Water Cresses – The crier of water cresses frequently travels seven or eight miles before the hour of breakfast to gather them fresh. There is a good supply in the Covent Garden Market brought along with other vegetables where they are cultivated like other garden stuff, but they are inferior to those grown in the natural state in a running brook, wanting that pungency of taste which makes them very wholesome. (Hanover Sq is on the south side of Oxford St, there is a circular enclosure in the middle with a plain grass plot. In George St, leading into the square, is the curious and extensive anatomical museum of Mr Heaviside the surgeon, to the inspection of which respectable persons are admitted, on application to Mr Heaviside, once a week.)

Slippers – The Turk is a portrait, habited in the costume of his nation, he has sold Morocco Slippers in the Strand, Cheapside and Cornhill, a great number of years. To these principal streets, he generally confines his walks. There are other sellers of slippers, particularly about the Royal Exchange who are very importunate for custom while the venerable Turk uses no solicitation beyond showing his slippers. They are sold at one shilling and sixpence per pair and are of all colours. (Somerset House is a noble structure built by the government for the offices of public business. The plate shows the west side of the entrance which contains a gate for carriages and two foot ways. A visit will amply repay the trouble of a stranger.)

Rabbits – The crier of rabbits in the plate is a portrait well known by persons who frequent the streets at the west end of town. Wild and tame rabbits are sold from ninepence to eighteen pence each, which is cheaper than they can be bought in the poulterers’ shops. (Portland Place is an elegant street to the north of Marylebone. From the opening at the upper end is a fine view of Harrow and the Hampstead and Highgate Hills, making it one of the airiest situations in town. The houses being of perfect uniformity and no shops or meaner buildings interrupting the regularity of the design, it is one of the finest street in London.)

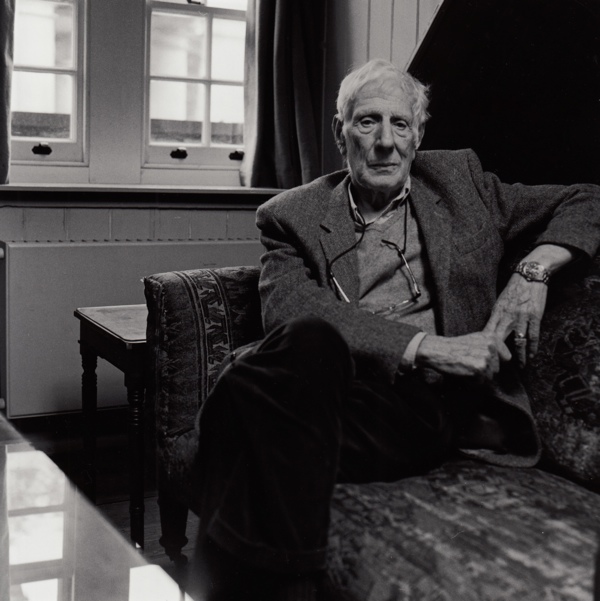

So Long, Jonathan Miller

A few years ago I met Jonathan Miller, the comedian, polymath and celebrated intellectual who died this week at the age of eighty-five, when he came in search of his East End roots

Jonathan Miller visited 5 Fournier St once, to see the house where his grandfather Abram lived and brought up his family more than a hundred years ago. Abram came to London from Lithuania in 1865 and worked as furrier in the attic workshop, the same room where Lucinda Douglas Menzies took this portrait of his grandson.

Jonathan did not know when Abram acquired the surname Miller. His grandfather arrived in the Port of London as an adolescent and found work as a machinist in the sweatshops of Whitechapel, where he met Rebecca Fingelstein, a buttonhole hand, whom he married in 1871. Somehow Abram worked his way up to become his own boss during the next ten years, running his own business from premises at 5 Fournier St by the time his son (Jonathan’s father) Emanuel was born in 1892, as the youngest of nine siblings. Emanuel’s sister Clara remembered how the children fell asleep listening to the whirr of sewing machines overhead.

As a supplier of fur hats to Queen Victoria and bearskins to the Grenadiers, Abram aspired to be an English gentleman with a pony and trap. Yet, at 5 Fournier St, the horse had to be kept in the back yard which meant leading it through the front hall, blindfolded in case it reared up at the chandelier.

Jonathan’s aunt Janie wrote her own account of her childhood there – “We lived in a large Queen Anne House in Spitalfields and part of the house was taken over by my father’s business who was a furrier. Needless to say, we all had coats trimmed with fur… My earliest recollection was my first day at the infant school in Old Castle St, and I remember the summer holidays we spent in Ramsgate for two weeks, year after year.”

Janies’s younger brother Emanuel looms large in her narrative – “We moved to Hackney when he was eight and he went to Parminter’s School, and from there got a scholarship to the City of London School and then another scholarship to St John’s College, Cambridge. I remember spending a really lovely week in Cambridge for May Week, attending the concerts etc and meeting all Emanuel’s friends. After leaving Cambridge, he went to the London Hospital in Whitechapel where he qualified as a doctor and served in the 1914 war as a Captain RAMC, and helped to cure the shell-shocked soldiers.” It was a long journey that Emanuel travelled from his father’s beginnings in Whitechapel and, as Janie records, he rejected the family trade in favour of the medical profession, “Emanuel refused to go into the business, as he had been to Cambridge and wanted to be a doctor, and he won the day.”

Jonathan Miller did not recall Emanuel speaking about the East End. “I never talked to my father very much because I was always in bed by the time he was back from his work, so I was completely out of it,” he admitted to me, “I am only a Jew for anti-Semites. I say ‘I am not a Jew, I am Jew-ish!'”

Although intrigued to visit the house where his father was born and where his grandfather worked, Jonathan was unwilling to acknowledge any personal response. “I’m not interested in my ancestry,” he joked, “I’m descended from chimpanzees but I am not interested in them either.” Like many immigrant families that passed through Spitalfields, in Jonathan’s family there was a severance – the generation that moved out and rose to the professional classes chose not to look back. And for Jonathan it was a gap – in culture and in time – that could no longer be bridged, even as we sat in the attic where his grandfather’s workshop had been a century earlier. “I know nothing about their life here,” he confessed to me, gesturing extravagantly around the tiny room and wrinkling that famously-furrowed brow.

As one who has constructed his own identity, Jonathan rejected distinctions of religion and ethnicity in favour of a broader notion of humanity to which he allied himself. Yet he was proud to tell me that his father came back and founded the East London Child Guidance Clinic in 1927, acknowledging where he had come from by bringing his scholarship to serve the people that he had grown up among. “He was interested in juvenile delinquents and he was really the founder of child psychiatry in this country,” Jonathan explained me, and the work that his father began continues to this day – with the Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services on the Isle of Dogs housed in the Emanuel Miller Centre.

So I found a curious irony in the fact that the son of a leading figure in the understanding of child development in this country should admit to no relationship to his father, and therefore none to his family’s past either. When 5 Fournier St was renovated, the gaps between the floor boards were found to be crammed with clippings of fur and every inch of this old house bears the marks of its three hundred years of use. Constantly, people come back to Spitalfields to search for their own past in the locations familiar to their antecedents, yet often the past they seek is already within them in their cultural inheritance and family traits – if they could only recognise it.

Clearly, Jonathan Miller’s choice to study medicine was not unconnected to his father’s career. When Jonathan reminded me of the familar Jewish joke about asking the way to get to Carnegie Hall and receiving the reply, ‘Practice, practice!’, he suggested that the pursuit of fame as musicians and as comedians had proved to be an important means of advancement for Jewish people. And I could not but think of Jonathan Miller’s own distinguished work in opera and his early success with ‘Beyond the Fringe.’ It set me wondering whether ancestry had influenced him more than he realised, or was entirely willing to admit.

Eighteenth century roof joists, exposed during renovations, still with their original joiner’s numbers which reveal that the roof was made elsewhere and then assembled on site

Weatherboarding revealed between 3 and 5 Fournier St during renovations, indicating that until the mid-eighteenth century number 5 was the end of the street, before number 3 was built

Abram Miller arrived from Lithuania in 1865 and is recorded at 5 Fournier St in the census of 1890

Wallpaper at 5 Fournier St from the era of Abram Miller

Watercolour of Fournier St, 1912 – the cart stands outside number 5

Emanuel Miller was born at 5 Fournier St in 1892

“I remember the summer holidays we spent in Ramsgate for two weeks year after year.” Emanuel is on the far right of this photograph.

Fournier St in the early twentieth century, number 5 is the third house

5 Fournier St today, now the premises of the Townhouse

The hallway where the blindfolded horse was led through

Emanuel Miller as an old man

Jonathan Miller

Portraits of Jonathan Miller © Lucinda Douglas Menzies