The Mysterious Tree Huts Of Epping Forest

Who can resist the lure of the forest at Midsummer? Since Epping Forest is a mere cycle ride from Spitalfields, I paid a visit this week to seek refuge among the leafy shades. In the depths of the forest, I came upon these makeshift tree huts which fascinated me with the variety and ingenuity of their design.

Who can be responsible? Is it children making dens or land artists exploring sculptural notions? Clearly never weatherproof, they are not human habitations. I wondered if the sprites and hobgoblins had been at work constructing arbors for the spirits of the forest. But then I remembered I had seen something similar once before, Eeyore’s hut at the edge of the Hundred Acre Wood.

Some are elaborate constructions that are worthy of architecture and others merely collections of twigs which tease the eye, questioning whether they are random or deliberate. They conjure an air of ritualistic mystery and, the more I encountered, the more intrigued I became. So much effort and skill expended suggest deliberate purpose or intent, yet they remain an enigma.

You may also like to take a look at

Portraits Of Working Lads Of Whitechapel

These portraits were taken around 1900 at the Working Lads Institute, known today as the Whitechapel Mission. Founded in 1876, the Institute offered a home to young men who had been involved in petty criminal activity, rehabilitating them through working at the Mission which tended to the poor and needy in Whitechapel. Once a lad had proved himself, he was able to seek independent employment with the support and recommendation of the Institute.

The Working Lads Institute was the first of its kind in London to admit black people and Rev Thomas Jackson, the founder, is pictured here with five soldiers at the time of World War I

Stained glass window with a figure embodying ‘Industry’ as an inspiration to the lads

In the dormitory

Rev Thomas Jackson & the lads collect for the Red Cross outside the Mission

Click here to learn more about The Whitechapel Mission

You may also like to take a look at

At St Mary’s Secret Garden

The garden is currently open for plant sales on Tuesday and Friday from 10am until 1pm

St Mary’s Secret Garden is situated in a quiet back street in Shoreditch and it comes as a welcome surprise to discover this verdant enclave amongst the dense maze of streets and housing that surround it. Yet two hundred years ago, this area North of Old St was the preserve of market gardens and nurseries, before the expansion of the city rendered what was once commonplace as the exception.

In 1986, some volunteers cultivated plants upon a piece of wasteground and, more than a quarter century later, there are well-established trees and a density of luxuriant growth that propose a convincingly leafy grove worthy of being described as a secret garden. You walk through the gate and you leave the realm of concrete and enter the realm of plants. Here nature is not something to be eradicated but is encouraged, where the enclosing trees induce a state of calm and urban anxieties retreat.

One overcast morning, with fine rain blowing in the wind, I cycled over to explore this Shoreditch Eden. I followed a path through an overarching stand of hazels with beehives in a line, leading round to the greenhouse and an old market barrow used to display plants for sale, while beyond this lay a vegetable garden organised in raised beds and a peaceful herb garden with a huge bay tree at the centre, with plants selected for their scent and texture.

Once you have made this journey you are at the centre of St Mary’s Secret Garden, and when I sat here alone to contemplate the peace, an hour passed before I realised it. Clearly it is not just me that finds gardens therapeutic because, as well being open to the public, St Mary’s runs gardening sessions for people with disabilities of all kinds.

Anyone can come to St Mary’s Secret Garden to seek solace. You can volunteer, take gardening courses, rent space to grow vegetables, and buy plants and seeds cheaply. Or you can simply escape the city streets to sit and dream surrounded by the green leaves – as I did – enjoying horticultural therapy.

Victoria Fellows and Israel Forrest planting Scabious

The garden where I lost an hour.

You may also like to read about

Heather Stevens, Head Gardener at the Geffrye Museum

The Gentle Author’s Coronavirus Diary

Oxford St in March

Early in the lockdown I pulled the volume of Samuel Pepys’ diary for 1665 from the shelf and, as my daily exercise, wandered over to St Olave’s in Seething Lane to walk in his footsteps through the vacant city.

At first, his diary consoled me like a dark mirror, describing a tragedy so much grimmer and more extreme than in our own times. It was at the end of April that he noted ‘Great fears of the Sickenesse here in the City, it being said that two or three houses are already shut up.’ Yet with every day that passed as the numbers of deaths increased, the difference in our circumstances lessened and his words acquired greater immediacy for me.

I took off my watch and let time go adrift since there were no longer any appointments or meetings. From that moment I forgot which day of the week it was, and the rituals of a daily walk and cooking dinner prevailed as the measure of time.

Searching for objective news, I deliberated each evening over the ascendant curve of the mortality rate, willing it to level off and decline until my anxious curiosity was rewarded by the realisation that these figures were unreliable and the true numbers were much higher.

I struggled to write of my experience because I was thinking of those who were suffering while I had the good fortune to remain healthy. As long as I was able to sit safely at home, this crisis was happening to others elsewhere but, without fail, every day on my walk I encountered an ambulance in the street as a constant reminder that it was all around me.

I began sleeping later, discovering that it was the traffic noise which previously woke me early each morning. I slept again as I did when a child, falling off the edge of consciousness into a soft dark oblivion and awakening to birdsong to find the world unfamiliar, as if – every morning – I were a traveller returning from a long journey to wonder at the changes.

Like Pepys, I was grateful that I had written my will and my affairs were in order. I am older than Pepys who was thirty-six years in 1665 and I feel I have already lived many lifetimes, even if I am not ready to leave this one. For the first time I found I was grateful that my parents are dead, since they have been spared these times. I realised was mentally preparing myself for whatever might come.

Each Friday, I cycled to deliver essential supplies to a couple of older friends in West London who live alone and of whom one was shielded. I shall never forget the solitariness of my first trip as the only cyclist in Oxford St on a cold afternoon in spring, traversing the lonely city as if I were the last human alive. Each week, more boards appeared upon the closed-up shops, seemingly in anticipation of the gathering apocalypse. I changed my route, cycling through the back streets of Bloomsbury and Marylebone in a vain hope of avoiding exposure.

I did the most conscientious spring clean of my house I have ever done and sewed all the missing buttons back on my clothes. I did it all slowly. I darned my quilt and I lay on the floor for two days, sewing patches on the sofa where the cat had torn it apart. Each day, I watered the garden and delighted in the plants flourishing as they gained inches in height from one day to the next in the exceptionally warm spring.

Other writers have written of their relative ease in adapting to the lockdown, since our work is solitary by nature and, over years, we learn to be comfortable with our own company. Thus it was with me too, until I fell into a hole when the coronavirus struck.

The virus – and my dawning recognition of the scale of the calamity – have left me with a mental paralysis. I had always been able to force myself to write, resisting tiredness, laziness or indolence. It is different now. I cannot force myself any more, I have to wait until the impulse arises. This is a significant departure for one with such a puritanical work ethic, yet for the first time in years the dark rings have gone from under my eyes. Now I can sit with the cat on my lap in the sunlight and spend the afternoon looking out at the garden, letting my thoughts drift into daydreams just I did in childhood.

When I picked up Pepys’ diary again, I discovered I had fallen out of sympathy with him. At the time of writing this, the cumulative death toll in London has passed ten thousand, as many people have died as perished in a single week in 1665 in a much smaller city. I realised that the quality of Pepys’ diary lies in its emotional authenticity, including some callous observations which make uncomfortable reading. At the height of the plague, he was filled with delight and self-satisfaction that his career was in its ascendancy and his bank account was growing. He was shocked when his coachman was struck down with the plague mid-journey in Holborn and horrified when confronted at night by a corpse on a stretcher on the watermen’s stairs, yet he lived in a bubble of privilege that permitted him to compartmentalise with astonishing disregard.

Once I recovered sufficiently to resume my weekly deliveries by bicycle, I found the city had changed with more people on the streets, dispelling the ghost town atmosphere that had pervaded. I want London to renew itself now, but I do not want it to return to how it was before. I have grown accustomed to the peace. My watch sits on my desk – still ticking – keeping the time of that earlier world before all this happened. I wonder when I shall put it on again.

Trafalgar Sq in March

You may also like to read about

Charles Jones, Gardener & Photographer

Garden scene with photographer’s cloth backdrop c.1900

These beautiful photographs are all that exist to speak of the life of Charles Jones. Very little is known of the events and tenor of his existence, and even the survival of these pictures was left to chance, but now they ensure him posthumous status as one of the great plant photographers. When he died in Lincolnshire in 1959, aged 92, without claiming his pension for many years and in a house without running water or electricity, almost no-one was aware that he was a photographer. And he would be completely forgotten now, if not for the fortuitous discovery made twenty-two years later at Bermondsey Market, of a box of hundreds of his golden-toned gelatin silver prints made from glass plate negatives.

Born in 1866 in Wolverhampton, Jones was an exceptionally gifted professional gardener who worked upon several private estates, most notably Ote Hall near Burgess Hill in Sussex, where his talent received the attention of The Gardener’s Chronicle of 20th September 1905.

“The present gardener, Charles Jones, has had a large share in the modelling of the gardens as they now appear, for on all sides can be seen evidence of his work in the making of flowerbeds and borders and in the planting of fruit trees. Mr Jones is quite an enthusiastic fruit grower and his delight in his well-trained trees was readily apparent…. The lack of extensive glasshouses is no deterrent to Mr Jones in producing supplies of choice fruit and flowers… By the help of wind screens, he has converted warm nooks into suitable places for the growing of tender subjects and with the aid of a few unheated frames produces a goodly supply. Thus is the resourcefulness of the ingenious gardener who has not an unlimited supply of the best appurtenances seen.”

The mystery is how Jones produced such a huge body of photography and developed his distinctive aesthetic in complete isolation. The quality of the prints and notation suggests that he regarded himself as a serious photographer although there is no evidence that he ever published or exhibited his work. A sole advert in Popular Gardening exists offering to photograph people’s gardens for half a crown, suggesting wider ambitions, yet whether anyone took him up on the offer we do not know. Jones’ grandchildren recall that, in old age, he used his own glass plates as cloches to protect his seedlings against frost – which may explain why no negatives have survived.

There is a spare quality and an uncluttered aesthetic in Jones’ images that permits them to appear contemporary a hundred years after they were taken, while the intense focus upon the minutiae of these specimens reveals both Jones’ close knowledge of his own produce and his pride as a gardener in recording his creations. Charles Jones’ sensibility, delighting in the bounty of nature and the beauty of plant forms, and fascinated with variance in growth, is one that any gardener or cook will appreciate.

Swede Green Top

Broad Beans

Stokesia Cyanea

Turnip Green Globe

Bean Longpod

Potato Midlothian Early

Pea Rival

Onion Brown Globe

Cucumber Ridge

Mangold Yellow Globe

Bean (Dwarf) Ne Plus Ultra

Mangold Red Tankard

Seedpods on the head of a Standard Rose

Ornamental Gourd

Bean Runner

Apple Gateshead Codlin

Captain Hayward

Larry’s Perfection

Pear Beurré Diel

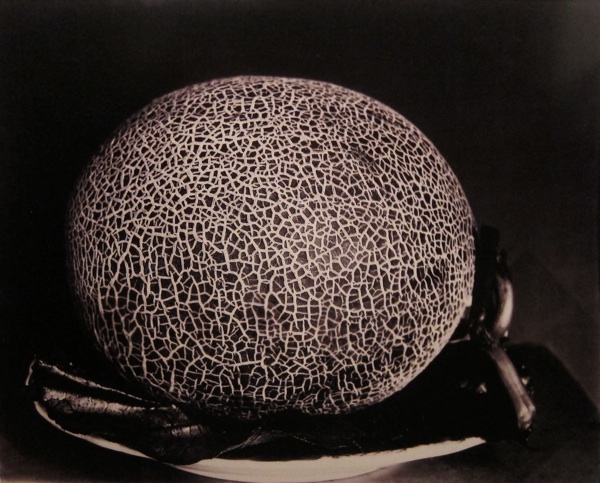

Melon Sutton’s Superlative

Mangold Green Top

Charles Harry Jones (1866-1959) c. 1904

Charles Jones photographs are currently being exhibited at the Michael Hoppen Gallery

You might also like to read about

The Secret Gardens of Spitalfields

Thomas Fairchild, Gardener of Hoxton

Buying Vegetables for Leila’s Shop

George Cruikshank’s London Summer

JULY 1838 – Flying Showers in Battersea Fields

Should you ever require it, here is evidence of the constant volatility of English summer weather, courtesy of George Cruikshank’s Comic Almanack published by Henry Tilt of Fleet St annually between 1835 & 1853, illustrating the festivals and seasons of the year for Londoners. (Click on any of these images to enlarge)

JUNE 1835 – At the Royal Academy

JUNE 1836 – Holidays at the Public Offices

JUNE 1837 – Haymaking

JULY 1835 – At Vauxhall Gardens

JULY 1836 – Dog Days in Houndsditch

JULY 1837 – Fancy Fair

AUGUST 1836 – Bathing at Brighton

AUGUST 1837 – Regatta

SEPTEMBER 1835 – Bartholomew Fair

SEPTEMBER 1837 – Cockney Sportsmen

You may also like to take a look at

Suresh Singh, The Cockney Sikh, On Zoom

Stefan Dickers and Suresh Singh will be in conversation on Zoom tomorrow, Friday 19th June at 6pm, showing Suresh’s family photographs and discussing his book A MODEST LIVING, MEMOIRS OF A COCKNEY SIKH. All are welcome at this free event which is part of Newham Heritage Month.

Click here for more information and tickets

Suresh Singh has been wearing this tank top since 1973

Perhaps everyone has a favourite piece of clothing they have worn for years? I always admired Suresh Singh’s jazzy tank top and I was astonished when he told me he has been wearing it for nearly half a century.

Suresh’s father Joginder Singh came to London from the Punjab in 1949 and the Singh family lived at 38 Princelet St longer than any other family in Spitalfields.

In our age of disposable fashion, the story of Suresh’s treasured tank top is an inspiring example of how a well made garment can be cherished for a lifetime.

“My mum made this tank top for me in 1973 when I was eleven. She had friends who all knitted and they had bits of wool left over – what you would call ‘cabbage’ – so mum collected all these balls of different coloured wool. Otherwise, they would have been chucked away. She kept them in her carrier bag with her needles that she bought at Woolworths in Aldgate East. They were number ten needles.

Mum said to me, ‘Suresh, I’m going to knit you a tank top.’ I never asked her because dad had taught me that I should always be patient, but I think mum saw the twinkle in my eyes and she knew I wanted one. I had asthma, so it was to keep my chest warm. She knitted it over the winter, from November to January. Mum never had the spare time to spend all day long knitting, she had to do it in bits as she went along and keep putting it away.

Mum did not follow a pattern, she just looked at me and sometimes took measurements. It started getting really huge, so I said, ‘Mum, it’s going to be too big.’ She had a sense of scale, she did not draw round me and cut a pattern. Mum never did that. She replied, ‘You’ll grow into it.’ The idea was you would slowly grow into new clothes.

When my tank top was finished, it hung down to my knees and the armholes were at my waist, but Mum was adamant I would grow into it. I loved it because it was all the rainbow colours. There was red, then yellow, then black, then pink and that really beautiful green. It was so outrageous. No other Punjabi kid had one like it. They all wore Marks & Spencer or John Collier grey nylon jumpers, but I had this piece of art. To me, it was a masterpiece. It was so beautifully made, it was mum’s pride and joy. When I wore it, people would exclaim, ‘That tank top, mate, it’s classic!’ I would say, ‘Yeah, my mum made it.’ Sometimes, because it was too big, I could pull it up and tie it in a knot at the front.

Mum made it with such love that I have always kept it. Eventually, my children wore it, but I am claiming it these days. It is a one-off. What made the tank top special for mum was that she was making it for her son. People often say it is a work of art but mum never went to art school. She picked up the tradition of making something for your child. She put so much love into it and I wear it today and it is still really nice. It gives me comfort and it keeps my chest warm.

It has got swag, you know what I mean?

It fits me now.”

Suresh and his mum at 38 Princelet St

Suresh Singh aged four

Suresh Singh & Jagir Kaur at 38 Princelet St (Photograph by Patricia Niven)

You may also like to read about

Click here to order a copy of A MODEST LIVING for £20