Tony Bock’s East Enders

Clock Winder at Christ Church, Spitalfields

Here are the East Enders of the nineteen seventies as pictured by photographer Tony Bock in the days when he worked for the East London Advertiser – the poncy dignitaries, the comb-over tories, the kids on the street, the market porters, the fascists, the anti-fascists, the shopkeepers, the sheet metal workers, the unions, the management, the lone dancers, the Saturday shoppers, the Saturday drinkers, the loving family, the West Ham supporters, the late bride, the wedding photographer, the clock winder, the Guinness tippler, the solitary clown, the kneeling politician and the pie & mash shop cat.

Welcome to the teeming masses. Welcome to the infinite variety of life. Welcome to the exuberant clear-eyed vision of Tony Bock. Welcome to the East End of fifty years ago.

Dignitaries await the arrival of the Queen Mother at Toynbee Hall. John Profumo kneels.

Children playing on the street in Poplar.

On the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral.

National Front supporters gather at Brick Lane.

Watching a National Front march in Hackney.

Shopkeepers come out to watch an anti-racism march in Hackney.

A family in Stratford pose in their back yard.

Wedding photographer in Hackney – the couple had been engaged many years.

West Ham fans at Upton Park, not a woman to be seen.

Sports club awards night in Hackney.

Dancers in Victoria Park.

Conservative party workers in the 1974 electoral campaign, Ilford.

Ted Heath campaigns in Ilford for the General Election of 1974.

Ford workers union meeting, Dagenham.

Ford managers, Dagenham.

Press operator at Ford plant, Dagenham.

At Speakers’ Corner, Hyde Park.

Mr East End Contest at E1 Festival.

The shop cat at Kelly’s Pie & Mash Shop, Bethnal Green Rd.

At the White Swan in Poplar.

Enjoying a Guinness in the Royal Oak, Bethnal Green.

Boy on demolition site, Tiller Rd, Isle of Dogs.

Brick Lane Sunday Market.

Clown in Stratford Broadway.

Saturday morning at Roman Rd Market.

Saturday night out in Dagenham.

Spitalfields Market porter in the workers’ club

Photographs copyright © Tony Bock

You may like to see these other photographs by Tony Bock

The Ceremony Of The Widow’s Sixpence

While my tours start tomorrow afternoon in Spitalfields at 2pm, over in Smithfield tomorrow morning at 11:30am hot cross buns will be distributed at St Bartholomew the Great.

Distribution of buns to widows in the churchyard of St Bartholomew the Great

St Bartholomew the Great is one of my favourite churches in the City, a rare survivor of the Great Fire, it boasts the best Norman interior in London. Composed of ancient rough-hewn stonework, riven with deep shadow where feint daylight barely illuminates the accumulated dust of ages, this is one of those rare atmospheric places where you can still get a sense of the medieval world glimmering. Founded by Rahere in 1123, the current structure is the last vestige of an Augustinian Priory upon the edge of Smithfield, where once martyrs were burnt at the stake as public entertainment and the notorious St Bartholomew Fair was celebrated each summer from 1133 until 1855.

In such a location, the Good Friday tradition of the distribution of charity in the churchyard to poor widows of the parish sits naturally. Once known as the ‘Widow’s Sixpence,’ this custom was institutionalised by Joshua Butterworth in 1887, who created a trust in his name with an investment of twenty-one pounds and ten shillings. The declaration of the trust states its purpose thus – “On Good Friday in each year to distribute in the churchyard of St. Bartholomew the Great the sum of 6d. to twenty-one poor widows, and to expend the remainder of such dividends in buns to be given to children attending such distribution, and he desired that the Charity intended to be thereby created should be called ‘the Butterworth Charity.'”

Those of use who gathered at St Bartholomew the Great on the Good Friday I visited were blessed with sunlight to ameliorate the chill as we shivered in the churchyard. Yet we could not resist a twinge of envy for the clerics in their heavy cassocks and warm velvet capes as they processed from the church in a formal column, with priests at the head attended by vergers bearing wicker baskets of freshly buttered Hot Cross Buns, and a full choir bringing up the rear.

In the nineteen twenties, the sum distributed to each recipient was increased to two shillings and sixpence, and later to four shillings. Resplendent in his scarlet robes, Rev Martin Dudley, Rector of St Bartholomew the Great climbed upon the table tomb at the centre of the churchyard traditionally used for that purpose and enacted the motions of this arcane ceremony – enquiring of the assembly if there were a poor widow of the parish in need of twenty shillings. To his surprise, a senior female raised her hand. “That’s never happened before!” he declared to the easy amusement of the crowd, “But then, it’s never been so cold at Easter before.” Having instructed the woman to consult with the churchwarden afterwards, he explained that it was usual to preach a sermon upon this hallowed occasion, before qualifying himself by revealing that it would be brief this year, owing to the adverse meteorological conditions. “God’s blessing upon the frosts and cold!” he announced with a grin, raising his hands into the sunlight, “That’s it.”

I detected a certain haste to get to the heart of the proceedings – the distribution of the Hot Cross Buns. Rev Dudley directed the vergers to start with the choir, who exercised admirable self-control in only taking one each. Then, as soon as the choir had been fed, the vergers set out around the boundaries of the yard where senior females with healthy appetites, induced by waiting in the cold, reached forward eagerly to take their allotted Hot Cross Buns in hand.

The tense anticipation induced by the chill gave way to good humour as everyone delighted in the strangeness of the ritual which rendered ordinary buns exotic. Reaching the end of the line at the furthest extent of the churchyard, the priests wasted no time in satisfying their own appetites and, for a few minutes, silence prevailed as the entire assembly munched their buns.

Then Rev Martin returned to his central position upon the table tomb. “And now, because there is no such thing as free buns,” he announced, “we’re going to sing a hymn.” Yet we were more than happy to oblige, standing replete with buns on Good Friday.

The Priory Church of St Bartholomew the Great, a century ago

John Betjeman once lived in this house overlooking the churchyard.

The ceremony of the Widow’s Sixpence in the nineteen twenties.

“God’s blessing upon the frosts and cold!”

A crowd gathers for the ceremony a hundred years ago

Hungry widows line up for buns

The churchyard in the nineteenth century

Rev Martin Dudley BD MSc MTh PhD FSA FRHistS AKC is the 25th Rector since the Reformation

Testing the buns

The clerics ensure no buns go to waste

Hymns in the cold – “There is a green hill far away without a city wall…”

The Norman interior of St Bartholomew the Great at the beginning of the twentieth century

The Gatehouse prior to bombing in World War I and reconstruction

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

Udham Singh, The Patient Assassin

A few tickets are left for my tours this weekend: www.thegentleauthorstours.com

Udham Singh

On this day, we remember the victims of the mass shooting of 13th April 1919 at Jallianwala Bagh, known as the Amritsar Massacre, in which between four hundred (low estimate) and fifteen hundred (high estimate) were shot by British soldiers at the instruction of Sir Michael O’Dwyer, Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab.

Although this event of a century ago might appear remote, there is a direct connection with Spitalfields because Udham Singh, who survived the massacre as a child, came to London in the thirties and lodged in Artillery Passage before taking action in 1940 to avenge the atrocity.

Udham Singh is widely remembered in his home country but in here in Spitalfields, and indeed throughout Britain, he almost unknown. In common with many figures of such renown, myths have grown up around Udham Singh, fuelled by multiple films and representations in popular culture, yet his story is real and this is how I understand it.

During World War I, a significant number of Indian soldiers fought for Britain. Yet British rulers were increasingly concerned by anti-colonial activities, in particular by the pro-independence Ghadar party, and they recognised a need to suppress them.

On 13th April 1919, over twenty thousand unarmed people were assembled at Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar, to celebrate the sikh festival of Baisakhi. At the instruction of Sir Michael O’Dwyer, Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab, soldiers were sent under the command of Brigadier General Reginald Dyer and they shot the crowd of men, women and children, indiscriminately.

Udham Singh was an orphan of seven years old and he claimed to have been present serving water to the picnicking crowd, witnessing the massacre and receiving a bullet wound in his arm. Although this was contested by the British authorities for lack of proof, what is certain is that he joined Ghadar party in response to the events of that day and made it his life’s purpose to seek revenge.

The Amritsar Massacre was a turning point that led moderate Indians to turn against British rule and was one of the darkest moments in the history of the British in India, but Rudyard Kipling justified it. In 1927, at the death of Brigadier General Reginald Dyer – known as the Butcher of Amritsar – who ordered the soldiers to shoot at the crowd in the park, Kipling wrote, ‘He did his duty as he saw it.’

Udham Singh came to London in 1934, aged twenty-two, and led a transient existence. He told Scotland Yard he lived at Nayyar’s warehouse, 30 Back Church Lane, Whitechapel, and 4 Duke St, Spitalfields, yet he was registered on the electoral roll at 4 Crispin St where he shared with thirteen pedlars. Another pedlar believed he lived with them in Adler St, Aldgate, as well as at 15 Artillery Passage.

On 13th March 1940, Sir Michael O’Dwyer gave a speech at the Caxton Hall to a meeting of the East India Association and the Central Asian Society. Udham Singh attended, carrying a book in which he had cut out the pages to conceal a gun and, at the end of the meeting, he shot O’Dwyer twice, killing him.

After a hunger strike and force-feeding at Brixton Prison, Udham Singh came to trial on 4th June at the Old Bailey where he explained his motive eloquently, ‘I did it because I had a grudge against him. He deserved it. He was the real culprit. He wanted to crush the spirit of my people, so I have crushed him. For full twenty-one years, I have been trying to seek vengeance. I am happy that I have done the job. I am not scared of death. I am dying for my country. I have seen my people starving in India under the British rule. I have protested against this, it was my duty.’

After being declared guilty, Udham Singh made a speech which the judge ruled could not be made public and that was not published until 1996, in which Singh declared, ‘I say down with British Imperialism. You say India do not have peace. We have only slavery. Generations of so-called civilisation has brought us everything filthy and degenerating known to the human race. All you have to do is read your own history.’

On 31st July, Udham Singh was executed by hanging at Pentonville Prison. In 1974, his remains were exhumed and repatriated to India where they were received by Indira Gandhi and today he is revered as a martyr in his homeland.

I learnt of the presence of Udham Singh in Spitalfields from Parkash Kaur who lives on the Holland Estate beside Petticoat Lane. Suresh Singh, author of A Modest Living, Memoirs of a Cockney Sikh, introduced me to Parkash who told me how she ran the first sikh grocers in the East End with her late husband Jarnail Singh at 5 Artillery Passage.

She recalled Suresh’s father Joginder who came to London in 1947 and became a close friend of her husband, saying ‘They often spoke of the assassin Udham Singh who lodged in 15 Artillery Passage in the thirties.’

Udham Singh lodged on the first floor at 15 Artillery Passage in the thirties

Jarnail Singh outside his grocery shop at 5 Artillery Passage

Portrait of Parkash Kaur by Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

Vera Hullyer, Parishioner of St Dunstan’s

This is Vera Hullyer sitting in front of the cupboard in the parish room where she keeps the vases and other paraphernalia she uses for creating the spectacular floral displays at St Dunstan’s – just one of myriad ways she has been involved with this ancient East End church since she first came here in 1945. Vera’s life has been interwoven with that of St Dunstan’s and its community over all these years, and she has become its devoted custodian, captivated by its mythic history and speaking of the distant past as vividly as she describes events of recent years.

Older in origin even than the Tower of London, St Dunstan’s once served the entire area now defined by the Borough of Tower Hamlets, which means that until Christ Church was built in the eighteenth century it was the parish church for Spitalfields. A wooden church dedicated to All Saints was built in Stepney after St Augustine’s conversion of the English in the sixth century and St Dunstan himself built the first stone church here in 952. A rough hewn stone relief from his time survives today, set into the wall behind the altar.

Along Fieldgate St from Whitechapel, I followed the route of the former path across the fields to visit this low-set medieval ragstone church that for centuries stood among orchards and farms until the modern East End grew up around it, spawning no less that sixty-seven “daughter” parishes out of the former rural parish of St Dunstan’s. Stepping in from the August rain and placing my umbrella in the stand, I was greeted by that distinctive silence which is unique to old stone buildings, and standing there in the gloom to survey the scene beneath the vast wooden roof, like a great upturned ship, I realised could have been in a country church almost anywhere in England.

A door opened at the far end of the chancel, spilling illumination into the half-light, and Vera came out of the shadows with nimble steps to greet me, shepherding me kindly to the octagonal parish room, where she made me a cup of tea and I was able to dry out my raincoat while she told her story.

I had an aunt that lived nearby in Stepney, she stayed here all through the war and had her roof blown off seven times. And my mother promised me that when the war ended we could come up from Fordingbridge, where we lived, to visit her for a holiday. So we came in August 1945 for VJ night, and I remember the church bells and the hooters on the river. Next day, we went up to Buckingham Palace and joined the crowd up against the railings.

I came to stay with my aunt every year after that for holidays, until 1953 when I came to London to work at the Air Ministry and I lived with her for the first two years. I was young and impecunious and seventeen and three quarters – people didn’t really go away from home then as they do now.

I’m half a Londoner, on my father’s side – he was born in Lambeth – and that bit came through. I’m a very different person now than if I had stayed down in Fordingbridge. Because I had been up to London for holidays, I knew my way around and I enjoyed it. I worked for several officers who had been in the war and Spitfire pilots who had been promoted – for a young girl it was very exciting. I was responsible for ordering and making sure that all the radio parts were in stock. From the Air Ministry, I went to be PA to a senior officer in Whitehall and I was there all through the Suez crisis and when Cyprus was partitioned.

I moved into a hostel in Queensgate, Kensington, in Spring 1955. It was a nice area, but there were four of us to a room. You got bed, breakfast and an evening meal, and the food was terrible. This was before fridges, and I acquired an ability to drink black Nescafe and toast made on the gas fire. At twenty-two, I moved out to Chiswick because we could afford a shared flat. But I still kept on coming to St Dunstans, and when I got married I came to live here and never moved again.

From when I first came to London, I joined the church badminton club to get to meet people. I met my husband, Charlie Hullyer, through the club, we were members of a big group of people there and I knew him for quite a while before we got married. He worked at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry as a carpenter. He made the frames for the bells and his last job, before he died in 1981, was to make a frame for the bells at Canterbury Cathedral. We got married at St Dunstan’s in 1965 and my son was baptised here. Charlie had a flat because he was the last child to leave home and he took it over after his parents died. So when we got married, we had somewhere to live – we didn’t have to move out like most people did. It was very difficult for the children of families to find homes locally and stay here, that’s why many East End families are split.

When I first came to the Ocean Estate, it was a bomb site and we used to walk my aunt’s dog there and there was this smell I will never forget. Then the flats went up. Most people were living in two-up two-downs, with no bathroom and a toilet in the backyard. Some were still living in bomb damaged homes. People were worn out, they had been evacuated and come back, and many had lost family in the bombing. So they were delighted with the new flats, it was real step up and it was luxurious.

The population then was old East Enders and Jewish people, but it’s changed a lot since 1953 and now it’s changing again. The Jewish people have all gone, and West Indians and Bangladeshis came in. It was all social housing then and people were poor. But the new housing is a mixture of some to buy and some to rent, so we have young professionals today who work in the City or at Canary Wharf. Whereas before it was just secretaries and machinists in the garment trade, while the men all worked in the docks.

Yet all the changes that Vera has seen are set in perspective by her relationship with St Dunstan’s. “We fly the red duster,” she announced to me with raffish glee, referring to red merchant navy flag fluttering from the tower, “That’s because before the registrar at Trinity House was established, all births and marriages at sea wherever they took place in the world were registered here in St Dunstan’s parish register and those people were parishioners of St Dunstan’s.”

Over more than seventy years now, Vera has pursued a constant involvement with St Dunstan’s, as member of the parish church council, as a church warden, as a sidesperson and as member of the congregation too. She has read the lesson. She has raised money to replace the magnificent wooden roof and to renovate the elaborate churchyard railings. She has headed the 17th Stepney Cub Scouts and she has done the church flowers for the last twenty years. When her husband Charlie brought his carpentry skills to the construction of crosses for elaborate performances of the Stations of the Cross performed upon the streets of Stepney in the seventies, Vera was stitching costumes.

It all adds up to a rich existence for Vera Hullyer at the centre of her chosen community in this remarkable building – a charismatic meeting place with a long history of devotion, offering an endless source of tales of those who have gone before to inspire the imagination.

Vera at the Tower of London when she first moved to London to work at the Air Ministry in the Winter of 1953, aged seventeen and three quarters, in the bottle green coat that she bought with her first earnings.

This tenth century stone relief carving is a relic of the church built by St Dunstan in 952.

St Dunstans on a map of 1615.

Honest Abraham Zouch, Ropemaker of Wapping, died 16th July 1648.

The Carthage stone, a souvenir of a sailor’s visit to Tunis.

Spandrel over the West door – legend has it that the devil came to tempt St Dunstan when he was working at his anvil, and the saint tweaked the devil’s nose with his red-hot pincers.

Vera Hullyer first came to St Dunstan’s on VJ day in the Summer of 1945.

East End Blossom Time

Only a few tickets left for my tours at Easter: www.thegentleauthorstours.com

In Bethnal Green

Let me admit, this is my favourite moment in the year – when the new leaves are opening fresh and green, and the streets are full of trees in flower. Several times, in recent days, I have been halted in my tracks by the shimmering intensity of the blossom. And so, I decided to enact my own version of the eighth-century Japanese custom of hanami or flower viewing, setting out on a pilgrimage through the East End with my camera to record the wonders of this fleeting season that marks the end of winter incontrovertibly.

In his last interview, Dennis Potter famously eulogised the glory of cherry blossom as an incarnation of the overwhelming vividness of human experience. “The nowness of everything is absolutely wondrous … The fact is, if you see the present tense, boy do you see it! And boy can you celebrate it.” he said and, standing in front of these trees, I succumbed to the same rapture at the excess of nature.

In the post-war period, cherry trees became a fashionable option for town planners and it seemed that the brightness of pink increased over the years as more colourful varieties were propagated. “Look at it, it’s so beautiful, just like at an advert,” I overheard someone say yesterday, in admiration of a tree in blossom, and I could not resist the thought that it would be an advertisement for sanitary products, since the colour of the tree in question was the exact familiar tone of pink toilet paper.

Yet I do not want my blossom muted, I want it bright and heavy and shining and full. I love to be awestruck by the incomprehensible detail of a million flower petals, each one a marvel of freshly-opened perfection and glowing in a technicolour hue.

In Whitechapel

In Spitalfields

In Weavers’ Fields

In Haggerston

In Weavers’ Fields

In Bethnal Green

In Pott St

Outside Bethnal Green Library

In Spitalfields

In Bethnal Green Gardens

In Museum Gardens

In Museum Gardens

In Paradise Gardens

In Old Bethnal Green Rd

In Pollard Row

In Nelson Gardens

In Canrobert St

In the Hackney Rd

In Haggerston Park

In Shipton St

In Bethnal Green Gardens

In Haggerston

At Spitalfields City Farm

In Columbia Rd

In London Fields

Once upon a time …. Syd’s Coffee Stall, Calvert Avenue

Adam Dant’s New Studio

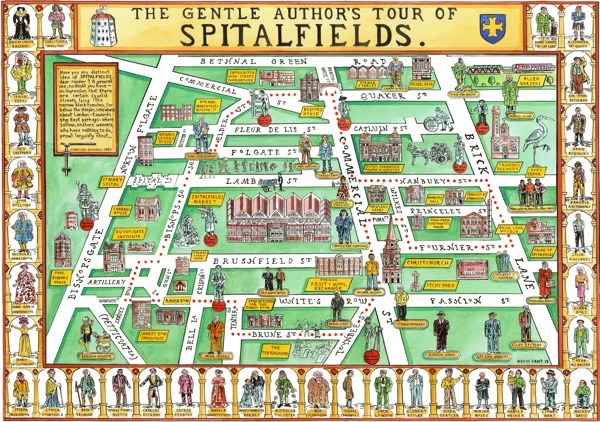

I was delighted to visit my long-time collaborator and Spitalfields Life Contributing Cartographer Adam Dant at his beautiful new studio high up in the roof of Sandys Row, London’s oldest Ashkenazi synagogue.

For over twenty years, Adam had a studio on Redchurch St but was forced to leave when it fell foul of redevelopment yet he landed on his feet in this magnificent garret, as he explained to me last week.

‘I wanted to stay in Spitalfields because I have a sentimental attachment to the place and it is the grist to my mill, where everything starts in terms of my work. The neighbourhood has changed a lot since I moved here in 1995. Ironically, there are as many empty spaces now as when I moved here, then they were empty because everything was derelict and nobody wanted them but now nobody can afford to rent them.

I knew some of the board members at Sandys Row Synagogue and I heard that the caretaker had left several years ago, and there was a garret and the top of the building that would make an ideal artist’s studio. It is nice and quiet here, and they still have services in the synagogue.

So I wrote them some charming letters and they thought it was a good idea to have an artist in residence, and here I am. The caretaker left her bright orange wood-chip wallpaper but I prefer a more muted orange. The colour honours William of Orange, whom the first congregation came over with, and today the interior of the synagogue is painted orange and cream in recognition.

This is exactly at the boundary of Tower Hamlets and the City of London is on the other side of the road, within spitting distance. It is very odd, the rubbish does always seem to end up on this side of the street. I have nice view of Broadgate, St Mary Axe and Tower 42 which lights up with different messages at night. The pub on the corner gets a bit noisy on a Friday night and I think the caretaker here did not like that.

I moved in three yeas ago, and I have redecorated it to suit my artistic preference and moved my library of London books in. It was the hottest day of the year and I had to carry everything up the stairs. During the pandemic, it was so quiet here it was eerie but I carried on working. It was just here alone, I picked up the post and made sure all was in order at the synagogue.

Then they took the roof off the synagogue and replaced it. I was out of here for several months and my murals got damaged but I quite like it because now it looks like they were here before I came.

The subjects of the wall painting are my personal heroes of Spitalfields history as featured on the map of The Gentle Author’s Tour of Spitalfields. There is Christopher Marlowe with his spaniel, Mary Wollstonecraft who was born not far from here in a house by the market, Jack Sheppard who was born round the corner in Whites Row, Anna Maria Garthwaite, the eighteenth century silk designer, Nicholas Culpeper and Emilia Lanier, Shakespeare’s Dark Lady and the first woman in this country to publish a book of poems under her own name.

It is like a fancy dinner party here with guests from history around the table which is from the cellar of the synagogue, they say it is a coffin table.’

You can visit Adam’s studio as part of an open day at Sandys Row Synagogue on Sunday May 1st noon-5pm. (£5 admission charge towards the upkeep of the synagogue and East End kosher fare served. For security reasons please do not bring backpacks and large bags.)

McDonalds’ map of Rome over the fireplace

Portraits of Anna Maria Garthwaite, Christopher Marlowe and Mary Wollstonecraft.

Portraits of Emilia Lanier Bassano and Nicholas Culpeper

Click here to buy a copy of The Gentle Author’s Tour of Spitalfields Map for £5

Thanks to the magnificent generosity of over 400 people who supported our crowdfund, The Gentle Author’s Tour of Spitalfields runs throughout the summer.

There are only few tickets left at Easter and we are now taking bookings until the end of May.

BOOK YOUR TOUR AT WWW.THEGENTLEAUTHORSTOURS.COM

Adam Dant’s limited edition prints are available to purchase through TAG Fine Arts

The East London Waterworks Scandal

Nick Higham author of The Mercenary River – Private Greed, Public Good: A History of London’s Water reveals a salient lesson from history, warning of the dangers of privatised water companies who invariably put profit above safety.

The largest cylinder ever made for a water-pumping engine, 1849 (courtesy of London Museum of Water & Steam)

Take a walk along the banks of the River Lea in the shadow of the Olympic stadium and your gaze might land on a collection of ancient pipes straddling the river, graffitied and begrimed. They look out of place beside the manicured lawns and landscaped pathways of the Olympic Park.

These pipes are all that remain of a waterworks on which hundreds of thousands of East Enders once depended for almost a century and which, in London’s last cholera outbreak in 1866, was responsible for the deaths of nearly 3,800 people.

The East London Waterworks was first set up at Old Ford in 1806. It was one of a raft of new water companies founded in east, west and south London to serve the expanding metropolis, and one of the more ramshackle. Its engineer was fired before he had laid a yard of water main. Its chairman was forced to resign following an insider share trading scandal and later fled the country when it was revealed that he had also embezzled thousands of pounds of public money. Later members of the board included Joseph Merceron, a corrupt magistrate and slum landlord dubbed the ‘Boss of Bethnal Green.’

Towards the end of its life, the company struggled to get enough water from the Lea to keep the East End supplied. It had to build an eighteen-mile pipeline to bring water from the Thames at Hanworth in the eighteen-sixties and large storage reservoirs in the Lea valley – now Walthamstow Wetlands – where a couple of the company’s old pumping stations still loom over the waterfowl. Even those measures proved insufficient in a series of droughts in the eighteen-eighties and nineties when the company had to ration water.

The East London Waterworks, one of eight private London water companies, was not all bad. In 1829, it recruited the young Thomas Wicksteed as its chief engineer and he introduced the latest high-pressure steam pumping engines developed for use in Cornwall’s mines. These engines were more than twice as powerful as the previous generation of steam-driven pumps built by the Birmingham partnership of Boulton & Watt and two-thirds more efficient. A handful survive and have been restored, massive constructions of cast iron and brass. You can see them at work at the London Museum of Water & Steam at Kew Bridge.

The East London Waterworks was also a pioneer of ‘constant supply.’ Originally, water in London was delivered only a few hours every two or three days. Turncocks toured, turning the water on and off street by street. In the eighteen-fifties, the East London Waterworks was the first to take on the challenge of keeping its mains charged permanently so water was always available to customers at the turn of a tap.

But the 1866 cholera outbreak marked a low point in the company’s history. In the eighteen-forties and fifties, the tidal reaches of the River Lea had become increasingly tainted with sewage and toxic discharges. Prompted by legislation, the company moved its intake upriver to Lea Bridge, beyond the reach of the tide. There it installed filter beds to purify its water – today the beds have been left to run wild, part sculpture park, part nature reserve.

But the water from Lea Bridge still entered a covered aqueduct leading down to the company’s original reservoirs at Old Ford, from which it was pumped into the mains. Somehow the water in these holding tanks became tainted with cholera.

There are several possible explanations. One was contamination from sewage discharges upstream, perhaps from new houses built as homes for the 1,500 employees at the government’s arms factory at Enfield. Another was that water from the polluted river was seeping through the walls of the reservoirs at Old Ford. It was a problem made worse by the fact that this was the last place where London’s magnificent new sewerage system by Joseph Bazalgette was not yet finished and untreated sewage still poured into the Lea.

Yet an official inquiry established the likeliest cause of the contamination was negligence on the part of Wicksteed’s successor as chief engineer who allowed his foreman, on a nod and a wink, to top up the Old Ford reservoirs – illegally – with unfiltered water when supplies ran short.

Not everyone accepted that the company’s water was to blame. Even though official statistics showed that ninety per cent of those who died from the cholera were in the East London Waterworks’ area. Many – including several medical officers of health in the East End – refused to accept the findings of Dr John Snow, published before his death in 1858, that cholera was a waterborne disease.

The City of London’s medical officer insisted the water could not be the cause because he had analysed it and found it free of impurities, but he was also on the East London Waterworks’ payroll.

The company’s directors appear – from the minutes of their meetings – to have been blithely unperturbed by the revelation that their service might be killing the customers. They scarcely discussed the issue, and contented themselves with passively approving whatever steps their engineer took in response to the outbreak. It was not an untypical response from the capitalists of the era. This was one reason why the East London Waterworks disappeared in 1904, when with all the London water companies were taken over by the publicly-owned Metropolitan Water Board. The shareholders were richly rewarded.

Today, London’s water is again in private hands and campaigners report that the Lea is contaminated by discharges of untreated sewage.

The pipes that brought the cholera to the East End, still in use today

East London Waterwoks Coppermills pumping station in Walthamstow

East London Waterworks manhole cover at the junction of Old St and Hoxton St

Announcement of water shortage, 1896

Thomas Wicksteed’s drawing of a Cornish high-pressure steam pumping engine (courtesy of London Museum of Water & Steam)

You may also like to read about