Happy Birthday East End Trades Guild!

In celebration of the tenth anniversary of the guild, I am hosting THE EAST END TRADES GUILD TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS on Saturday 3rd December, telling the stories of local shops and their origins in this traditional heartland for small traders.

A coveted EETG tote bag, a copy of the 2022 map of independent shops designed by Rob Ryan, and small gifts from guild members are included in the ticket, along with refreshments served by a member of the guild at the end of the tour.

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

Click to enlarge Martin Usborne’s photograph

These are the founder members of The East End Trades Guild who gathered at Christ Church, Spitalfields, ten years ago this week to summon their new organisation into being and speak collectively on behalf of all independent and proprietor-run businesses in the East End.

That night, the church was full and the anticipation immense as trumpets sounded in a fanfare from the gallery, resounding throughout Nicholas Hawksmoor’s masterpiece of English baroque, to announce the arrival of this bold endeavour.

Nevio Pellicci, the East End’s most celebrated host, his dark eyes shining with eagerness and looking flash in a three-piece suit, stepped up to the microphone to welcome everyone by revealing that among the many things the small traders had in common, they could be proud of the fact that none were registered in Luxembourg. He was greeted by a cheer worthy of a rock star.

As the opening speaker of the evening, Paul Gardner brought the house down by suggesting to the assembly,“I’m sure most of you are here just for the novelty of seeing me in a suit!” The Founder of the Guild, Paul had been shaking hands with guests as they arrived and now he recounted the history of his family business in Spitalfields commencing with his great-grandfather James, a Scalemaker, in 1870.

Two years before, an unrealistic rent demand threatened to put Paul out of business yet the public outcry after my story about this – which caused the landlord to reconsider – became the catalyst for the formation of the Guild. Paul spoke candidly of his own sense of vulnerability as a sole trader and of the struggles experienced by his devoted customers who are all small businesses. In speaking of the Guild, Paul described the elation he felt after attending the first meetings and many in the audience nodded their heads in recognition, acknowledging the camaraderie which the Guild has already fostered among the traders.

Next, Henry Jones of Jones Brothers’ Dairy and Shanaz Khan of Chaat Bangladeshi Tea House shared the platform. Born above the shop, Henry Jones told how his great grandfather and namesake drove the cattle from Aberystwyth in 1877 to start the dairy in Middlesex St. Surviving two World Wars and the bombings in the City of London, Henry had to reinvent Jones Bros as a wholesale supplier when supermarkets and chainstores took away his domestic business, and he spoke of the need for independents to share information and to speak with the authority of a collective voice.

Shanaz Khan had a different story to tell. Like Henry, she grew up above the family business which in her case was an Indian restaurant. Yet, although she only came to the East End ten years before, she was equally enthusiastic about the opportunity she has found here, and spoke of her commitment to use local suppliers and employ local people. When Shanaz opened up Chaat away from the curry houses of Brick Lane, it seemed a pioneering move, but the fashionability of Redchurch St – bringing in luxury brands – led to a punishing rent increase which was, in effect, a penalty for her hard work and success.

Drawing from these personal experiences, it fell to Shanaz to outline the intentions of the Guild – developing campaigns, giving voice to small businesses, creating a network for the members to share information and trade, offering advice, and building the local economy. Her passionate speech was the heartfelt climax of proceedings.

Ten years ago, as I walked through the excited throng where many traders were meeting each other for the first time, I could hear snatches of conversation. There was a lively discussion of the issues that need to be addressed, especially rents and council tax, but I also heard them saying, “I could supply you with that,” and “If you need those I’ve got them in stock.” There was a collective dynamic at work in the room as the traders followed their instincts, discovering ways they could help each other and – in that moment – I realised the Guild existed and had its own life.

Graphic by James Brown

Event photographs © Simon Mooney

Group photograph © Martin Usborne

You may also like the read about

The Founding of the East End Trades Guild

Burdekin’s London Nights

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

East End Riverside

As you will have realised by now, I am a night bird. In the mornings, I stumble around in a bleary-eyed stupor of incomprehension and in the afternoons I wince at the sun. But as darkness falls my brain begins to focus and, by the time others are heading to their beds, then I am growing alert and settling down to write.

Once I used to go on night rambles – to the railway stations to watch them loading the mail, to the markets to gawp at the hullabaloo and to Fleet St to see the newspaper trucks rolling out with the early editions. These days, such nocturnal excursions are rare unless for the sake of writing a story, yet I still feel the magnetic pull of the dark city streets beckoning, and so it was with a deep pleasure of recognition that I first gazed upon this magnificent series of inky photogravures of “London Night” by Harold Burdekin from 1934 in the Bishopsgate Library.

For many years, it was a subject of wonder for me – as I lay awake in the small hours – to puzzle over the notion of whether the colours which the eye perceives in the night might be rendered in paint. This mystery was resolved when I saw Rembrandt’s “Rest on the Flight into Egypt” in the National Gallery of Ireland, perhaps finest nightscape in Western art.

Almost from the beginning of the medium, night became a subject for photography with John Adams Whipple taking a daguerrotype of the moon through a telescope in 1839, but it was not until the invention of the dry plate negative process in the eighteen eighties that night photography really became possible. Alfred Stieglitz was the first to attempt this in New York in the eighteen nineties, producing atmospheric nocturnal scenes of the city streets under snow.

In Europe, night photography as an idiom in its own right begins with George Brassaï who depicted the sleazy after-hours life of the Paris streets, publishing “Paris de Nuit” in 1932. These pictures influenced British photographers Harold Burdekin and Bill Brandt, creating “London Night” in 1934 and “A Night in London” in 1938, respectively. Harold Burdekin’s work is almost unknown today, though his total eclipse by Bill Brandt may in part be explained by the fact that Burdekin was killed by a flying bomb in Reigate in 1944 and never survived to contribute to the post-war movement in photography.

More painterly and romantic than Brandt, Burdekin’s nightscapes propose an irresistibly soulful vision of the mythic city enfolded within an eternal indigo night. How I long to wander into the frame and lose myself in these ravishing blue nocturnes.

Black Raven Alley, Upper Thames St

Street Corner

Temple Gardens

London Docks

From Villiers St

General Post Office, King Edward St

Leicester Sq

Middle Temple Hall

Regent St

St Helen’s Place, Bishopsgate

George St, Strand

St Botolph’s and the City

St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Smithfield

Images courtesy © Bishopsgate Institute

You might like to read these other nocturnal stories

On Christmas Night in the City

Night at the Brick Lane Beigel Bakery

Night at The Spitalfields Market, 1991

Martin White, Textile Consultant

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Martin White, aged two in 1933

“That was the difference between Philip & me,” explained Martin White, articulating the nature of the precise distinction between himself and his former business partner at Crescent Trading, the late Philip Pittack, “He was a Rag Merchant, whereas I am a Textile Consultant. I understand textiles, I know about suitings and have been dealing in them since 1946. Our different specialities complemented each other.”

Famous for his monocle and pearl tiepin, as well as his unrivalled knowledge, Martin White was one half of the duo known as Crescent Trading, in which today he is the sole trader. Possessing more than one hundred and twenty years of experience in the business between them, their continuous comedy repartee won them a reputation as the Mike & Bernie Winters of the textile trade until Philip died of Covid in 2020.

Martin is celebrated for his ability to make an offer on a parcel of textiles on sight. “Very few people know how to do it,” he admitted to me. “Philip & I went on a buying trip twice a year, but in the past I used to go buying every day.” Martin’s story reveals how he acquired his remarkable knowledge of textiles, developing an expertise that permits him obtain the quality fabrics for which Crescent Trading is renowned.

“My father, William White, was a leather merchant but he also had some boot repair shops and, because he was a bit of mechanic, he rebuilt boot repairing machines. And that’s what he wanted me to go into. We lived in a very nice house in Shepherd’s Hill, Highgate, but unfortunately my father was diabetic who didn’t believe in conventional medicine. He was a herbalist and he became very ill in his forties and died at forty-six.

I started work at fourteen for my two uncles, Joe Barnet & Mark Bass (known as Johnny,) at their shop in Noel St off Berwick St in 1946. I was a little boy who didn’t know anything and in those days fabric was rationed and very hard to come by. Joe used to go up north and he had contacts in Manchester who used to get him stuff from the mills. It was a tiny shop and everything we got we sold immediately. They were making thousands every week and I was getting two pounds a week for carrying the fabric in and out. I used to like touching the fabric and that’s how I learnt about it.

While I was there, my father died and another of my uncles, David Bass, came to see my mother and he said he would take me to work for him and give me a wage, so she wouldn’t have to worry about me. But when the two uncles I was already working for heard this, Joe Barnet sent his wife Zelda to my mother to say that, if I worked for David, I would take all their customers from Noel St and it would ruin their business. So Joe Barnet told my mother he would look after me. He had just formed an association with a government supply business in Bethnal Green and he asked me to go down there and watch because he didn’t trust them, and that was my job.

So the first Friday came and he gave me five pounds, that was my wages. The following week, I found a parcel of cloth for sale in Brick Lane and I bought three thousand yards at a shilling a yard and I sold it for three shillings and sixpence a yard. The next Friday, Joe gave me fifteen pounds but I realised I had no chance of furthering myself with him, so I left and started working with another boy of my own age, Daniel Secunda. We were fifteen years old. We had no premises. We used to stand by the post at the corner of Berwick St, and people came to us with samples and goods to sell. We took the samples and sold them, and we made a good living between the two of us. We were young and we were carefree.All the money we earned, we spent it. We were happy. We went out every night. And that lasted for about three years, before the business got hard when rationing ended.

Then I met a guy who wanted to go into business properly with us, Pip Kingsley. He took premises in Berwick St and formed P. Kingsley & Co. After a while, it became apparent that while Danny was a very good-looking and likeable fellow, I was the worker out of the two of us. So Kingsley got rid of Danny and rehired an old job buyer who had retired, Myer King, and we started working together. He was an Eastern European, a very big man who couldn’t read or write. He had the knack of job buying ‘by the look.’ He’d go into a factory and make an offer for everything on the spot. This method of buying was different to anything I had ever seen but it worked. By working with him, I learnt what to do and what not do. And that knowledge was the basis of how I did business from then on.

I was happy working with Kingsley & Myer, but then I met my wife to be, Sheila, and I decided that I wanted my share of the money that my father had left in trust for my younger brother Adrian and me when we were twenty-one. I wanted to get married, and Sheila had been married before and she had a little boy. She was very beautiful. She’s eighty-five and she’s still beautiful.

My brother Adrian was known as Eddie and, at the age of eleven while my father was dying, he contracted sugar diabetes, so they were both in hospital. In the next bed to him was George Hackenschmidt, a boxer who had done body-building and my brother became interested in this. It was a very sad thing, my dad died when they were both in hospital and an uncle said to Eddie, ‘When you get out, I’ll buy you anything you want,’ to make him feel better. So Eddie said, ‘I want a set of weights.’

It was back in 1945, Eddie was twelve and he got one hundred pounds worth of weights and equipped a gym in our garage, and he started doing these workouts in the American magazines that George Hackenschmidt had given him. Eventually, he became Charles Atlas’ body. They would take the head of Charles Atlas and put it on a photo of my brother in the adverts for body-building.

When we broke my father’s trust fund, Eddie was twenty-one and we each received eight hundred pounds. My brother only lifted weights and sat in the sun, so I said to him, ‘What are you going to do with this? Give it to me and we’ll be partners, and I’ll do all the work and you can sit in the sun.’

Now, I wanted to get married to Sheila and her father was a textile merchant but her family didn’t like who I was. One of them was A. Kramer who happened to be Dave Bass’ solicitor and he phoned me up to warn me off her. So I told him what he could do, and Sheila and I got married in a registry office in 1955. Sheila’s little boy was four and her father, Lou Mason, didn’t want him to suffer, so he came to see me at my business and I showed him what I was buying.

Then he approached me one day and asked if I was interested in looking at a parcel of goods he had found in Wardour St at a lingerie company called Row G. So I went to see the parcel and made an offer of seven hundred pounds on sight. Lou said, ‘We don’t do business that way,’ and I said, ‘I’ll do it how I want to do it.’

The owner said, ‘No,’ but two weeks later I went back. He took the seven hundred pounds and it was all sold within two weeks for eighteen hundred pounds. My father-in-law said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this. It’s wonderful, why don’t you come and work with me?’ I couldn’t say, ‘No,’ to my father-in-law. There was no option. I said to my brother, ‘We’ll have to part company and I’ll give you your money back.’ He never forgave me.

The very first deal that came along was Cooper & Keyward, they had a lot of rolls of suiting and it came to two thousand pounds. But when I asked my father-in-law for the money to buy it, he said, ‘I’m a bit short this week.’ I just about had the two thousand pounds so I laid out the money myself and took the goods, and my father-in-law was able to sell it to his customers. On Friday, I said to him, ‘I need forty pounds to take my wife out,’ and he said, ‘We don’t spend money that way!’ So I fell out with my father-in-law. It turned out, he didn’t have the money to pay me because his business was going bankrupt.

I went round to get my goods which were in the basement of a shop in Berwick St and my mother-in-law was in the shop. A cousin came out and said, ‘You’re going to kill her, can’t we meet at the weekend and sort this out?’ At the meeting, my father-in-law accused me of being a liar but my wife’s aunt, Joyce, knew him and said to me, ‘I believe you.’ I never was a liar. She said to me, ‘If I lend you a thousand pounds, can you make a living?’

In Berwick St, Johnny Bass was trying to sell his stock at the shop where I had started work. The Noel St shop was full of fabric and he’d offered it to several people but no-one could assess what was there. He wanted four thousand pounds yet, because of my knowledge, I was able to cut a deal for two thousand four hundred pounds. It was Friday night and he said, ‘Give me some money.’ He’d just come of out of the bookmakers and he was penniless. I had a hundred pounds on me, so I gave him that and I had to find the rest of the money.

I went to get it from Joyce but she was in hospital. So I visited her and she said, ‘My husband Bert will get the money for you,’ and on the Monday he came with me to pay Johnny. Joyce had a property in Mansell St and I filled it up with the fabric and started selling it every day from there. Joyce was coming over to collect money from me in her handbag. She was charging me one hundred pounds a week rent plus interest, so I realised she thought I was working for her now but it wasn’t a partnership in my eyes and I wouldn’t go along with it.

I told her I wanted premises in Great Portland St and I needed money for that. It was agreed and that’s what we did. It was called the Robert Martin Company – Sheila’s son was called Robert. I got Daniel Secunda back to work with me. It was 1956, I had my own shop at last. And that’s how I became a textile merchant.”

Aged two, 1933

Aged three, 1934

Aged five in 1936

At school in Highgate, 1936

At a family wedding in September 1939. On the left are William & Muriel White, Martin’s parents. Beside them is Joe Barnet, Martin’s first employer, and his wife Zelda.

Martin’s brother Adrian (known as Eddie) who became the body of Charles Atlas

Martin’s brother Adrian (known as Eddie) who became the body of Charles Atlas

Martin White & Danny Secunda, his first working partner in 1956

Martin White & Philip Pittack, Crescent Trading Winter 2010

Martin White with his trademark monocle

Crescent Trading, Quaker Court/Pindoria Mews, Quaker St, E1 6SN. Open Sunday-Friday.

You may also like to read about

The Reopening of Crescent Trading

The Return of Crescent Trading

The Antiquarian Bookshops Of Old London

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

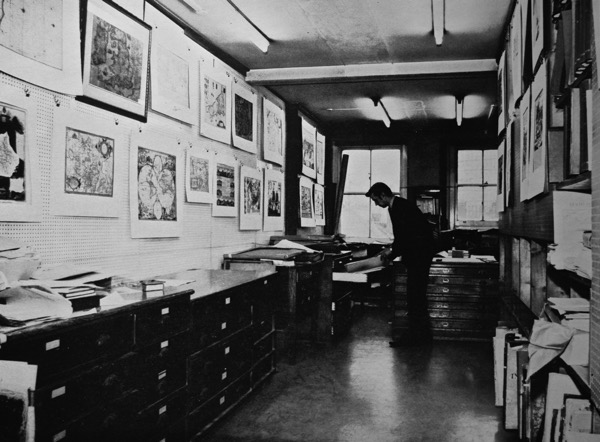

At Marks & Co, 84 Charing Cross Rd

When Mike Henbrey reminisced for me about his time working at Sawyer Antiquarian Booksellers in Grafton St and showed me these evocative photographs of London’s secondhand bookshops taken in 1971 by Richard Brown, it made me realise how much I miss them all now that they have mostly vanished from the streets.

After I left college and came to London, I rented a small windowless room in a basement off the Portobello Rd and I spent a lot of time trudging the streets. I believed the city was mine and I used to plan my walks of exploration around the capital by visiting all the old bookshops. They were such havens of peace from the clamour of the streets that I wished I could retreat from the world and move into one, setting up a hidden bedroom to sleep between the shelves and read all day in secret.

Frustrated by my pitiful lack of income, it was not long before I began carrying boxes of my textbooks to bookshops in the Charing Cross Rd and swapping them for a few banknotes that would give me a night at the theatre or some other treat. I recall the wrench of guilt when I first sold books off my shelves but I found I was more than compensated by the joy of the experiences that were granted to me in exchange.

Inevitably, I soon began acquiring more books that I discovered in these shops and, on occasion, making deals that gave me a little cash and a single volume from the shelves in return for a box of my own books. In this way, I obtained some early Hogarth Press titles and a first edition of To The Lighthouse with a sticker in the back revealing that it had been bought new at Shakespeare & Co in Paris. How I would like to have been there in 1927 to make that purchase myself.

Once, I opened a two volume copy of Tristram Shandy and realised it was an eighteenth century edition rebound in nineteenth century bindings, which accounted for the low price of eighteen pounds. Yet even this sum was beyond my means at the time. So I took the pair of volumes and concealed them at the back of the shelf hidden behind the other books and vowed to return.

More than six months later, I earned an advance for a piece of writing and – to my delight when I came back – I discovered the books were still there where I had hidden them. No question about the price was raised at the desk and I have those eighteenth century volumes of Tristram Shandy with me today. Copies of a favourite book, rendered more precious by the way I obtained them and now a souvenir of those dusty old secondhand bookshops that were once my landmarks to navigate around the city.

Frank Hollings of Cloth Fair, established 1892

E. Joseph of Charing Cross Rd, established 1885

Mr Maggs of Maggs Brothers of Berkeley Sq, established 1855

Marks & Co of Charing Cross Rd, established 1904

Harold T. Storey of Cecil Court, established 1928

Henry Sotheran of Sackville St, established 1760

Andrew Block of Barter St, established 1911

Louis W. Bondy of Little Russell St, established 1946

H.M. Fletcher, Cecil Court

Harold Mortlake, Cecil Court

Francis Edwards of Marylebone High St, founded 1855

Stanley Smith of Marchmont St, established 1935

Suckling & Co of Cecil Court, established 1889

Images from The London Bookshop, published by the Private Libraries Association, 1971

You might also like to read about

The Executions Of Old London

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Coinciding with the new exhibition EXECUTIONS at Museum of London Docklands, I present this fine election of execution broadsides. In the days before internet, television or cinema, public executions were a popular source of entertainment. I am grateful to Ed Maggs, fourth generation proprietor of Maggs Bros booksellers, who drew my attention to these gruesome wonders.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution Broadside of Henry Horler for the murder of his wife Ann Horler on 17th November 1852, at Sun St, Bishopsgate.

Ann Horler’s mother, Ann Rogers, came to take her daughter away from her husband Henry Horler on the night before the murder was discovered. She had been told that her daughter had been abused by her husband. Henry Horler insisted his wife would not go with her mother that night, but Mrs Rogers should return in the morning for her. The next morning Ann Horler was found dead.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of John Wiggins at Newgate, 15th October 1867, for the murder of Agnes Oakes on the morning of Wednesday 24th July at Limehouse. Printed with the trial and execution of Louis Bordier, a Frenchman charged with the murder of Mary Ann Snow on the 3rd September 1867 on Old Kent Rd.

Agnes Oakes lived with John Wiggins as his wife for about six months prior to the murder. Neighbours said they witnessed John beating Agnes and she had said she would leave him if he did not stop.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of Michael Barrett, the Fenian, and last man to be hanged in public, on the 26th May 1868, Newgate. Barrett was arrested for the “Clerkenwell Explosion” on 13th December 1867 which killed twelve people and injured many others. Barrett was the only Irish Republican to be convicted of the crime, five others were acquitted.

This tragic event occurred during an attempt to release Richard O’Sullivan Burke from prison. The explosion was misjudged and not only did it blast a sixty foot hole in the prison wall, (O’Sullivan Burke is thought to have been killed in the blast), a number of tenements on Corporation Lane were also destroyed.

The conviction appeared largely to be based on the fact Michael Barrett was a Fenian and that several witnesses claimed he may have been in London at the time. Barrett stated he was in Glasgow on the day of the explosion and if ‘there were 10,000 armed Fenians in London, it was ridiculous to suppose they would send to Glasgow for a person of no higher abilities than himself.’

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of John Devine for the murder of Joseph Duck in the early morning of 11th March 1863, Little Chesterfield St, Marylebone.

The condemned pleaded not guilty to the crime which appeared to result from a robbery that went wrong. The jury was sympathetic to Devine and, although the verdict returned was guilty, there was a strong recommendation to mercy, as they were of the ‘opinion that the prisoner inflicted the injuries on the deceased while in the act of robbing him; but, at the same time they thought he did not intend to murder him.’ The scene of the execution was described thus: ’There was not a large concourse assembled to witness the sad spectacle, nor was there exhibited by those present any of that unseemly demonstrativeness which they are wont to indulge in.’

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of the nurse Catherine Wilson for the murder by poisoning with colchicine of her patient Maria Soames in Albert St, Bloomsbury, on the 18th October 1856. The last woman to be publicly hanged in London.

This was Catherine Wilson’s second indictment for poisoning a patient, having been acquitted the first time round to the astonishment of many. When the first trial took place, on 16th June 1862, in the documents the accused appeared as Constance Wilson and was also occasionally found under the alias Catherine Taylor/Turner. Immediately, she was taken back in to custody and charged with the murder of Maria Soames. During the initial trial, the police had been busy putting together evidence of further victims and even exhumed several bodies, including that of Ann Atkinson, Peter Mawer and James Dixon, who was one of Ms. Wilson’s former lovers. In seven of these exhumed bodies a variety of poisons were found.

The Judge presiding said he had ’never heard of a case in which it was more clearly proved that murder had been committed, and where the excruciating pain and agony of the victim were watched with so much deliberation by the murderer.”

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of Dr William Palmer, for the poisoning of John Parsons Cook at Stafford. Dr Palmer was described by Charles Dickens as ‘The greatest villain that ever stood at the Old Bailey’ in his article on ’The Demeanor of Murderers’. He is also referenced in several novels and an Alfred Hitchcock film.

He was also suspected, although never indicted, of the murder of his four children, all of whom died in infancy, his wife Ann Palmer, Brother Walter Palmer, a house guest Leonard Bladen, and his mother-in-law, Ann Mary Thornton. The doctor benefited financially from all of these deaths.

Dr Palmer was executed at Stafford Prison Saturday 14th June 1856. Although not mentioned in this broadside, the prisoner was said to have had an interesting exchange with the prison governor moments before his death. When Dr Palmer was asked to confess his crimes, the exchange went thus:

Dr Palmer – ’Cook did not die from strychnine.’

Prison Governor -’There is not time for quibbling – Did you or did you not kill Cook?’

Dr Palmer – ’The Lord Chief Justice summed up for poisoning by strychnine.’

In the trial text, it is stated Dr Palmer reiterated he was: ‘innocent of poisoning Cook by strychnia.’

The Judge stated in his summation: ‘Whether it is the first and only offence of this sort which you have committed is certainly known only to God and your own conscience.’

Dr Palmer became notorious for his supposed crimes. It was said 20,000 people attended his execution and a wax figure of him was displayed at Madame Tussauds in the Chamber of Horrors from 1857 – 1979.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Trial broadside of Thomas Cooper,‘would-be’ highwayman, for the murder of Timothy Daly, policeman, and also for shooting at and maiming, with intent to murder, Charles Mott (a baker), and Charles Moss (another police officer) on 5th May at Highbury.

The defence, Mr Hory, addressed the jury, saying ‘for the first time during the seven years that he had been at the bar, he was called upon to address a jury upon a charge, conviction upon which was certain death. He almost felt that his anxiety would defeat itself. He could not help referring to different published statements, most of them monstrous perversions of established fact, and all calculated to excite the prejudices of a jury. When he saw these he could hardly fancy they lived in an enlightened age’.

Mr Hory made the case that the prisoner was not of sound mind, citing attempts of suicide, and claims of being Dick Turpin and Richard III. But this defence was unsuccessful with the jury reached a verdict of guilty, and Thomas Cooper was sentenced to death and executed July 7th 1842.

(Click on the image to enlarge and read the text)

Execution broadside of Charles Peace the notorious Blackheath burglar, for the murder of Arthur Dyson at Banner Cross, on the 29th November 1876.

Charles Peace murdered Arthur Dyson after become obsessed with Mr Dyson’s wife. Then Peace went on the run for two years with a £100 reward on his head, until he was betrayed by his mistress, Mrs Sue Thompson, who revealed his whereabouts to the police. She never received her expected reward as the police claimed her information did not lead directly to Peace’s arrest. He was caught on 10th October 1878, by Constable Robinson, who Peace shot at five times.

Subsequently, a waxwork figure of Charles Peace featured at Madame Tussaud’s, and two films and several books were produced about his life and crimes.

Images courtesy of Maggs Bros

You may also like to read about

Dorothy Rendell’s East End Portraits

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

Dorothy Rendell trained at St Martin’s School of Art during the Second World War and was encouraged by Henry Lamb, Carel Weight and Orovinda Pissarro at the beginning of her career. While teaching art at Harry Gosling School in Whitechapel for forty years, she undertook portraits of her favourite pupils and, subsequently, drew people in the doctor’s waiting room at the Jubilee St Practice. These dignified and tender images comprise an important social record of East Enders in the post-war years.

“When I started teaching I thought I would teach in the West End but they would not take women, so I had to move to the East End – but I don’t regret that at all because I got so wrapped up in it and there were all these places where I could go and draw,” Dorothy admitted to me.

“This little boy was one of the pupils I taught. A little horror! He’d been badly behaved – so the head teacher told me, ‘Take him and make him sit for you!’ So he had to sit still for about two or three days. I think I did a painting of him too”

“This is a nice little girl who had a terrible life. She was pretty and I liked her, so I drew her. I think I probably went to her house. It was squared up for a painting but I don’t know what happened to the painting. Children are very good to draw as long as they are not commissioned, when they are commissioned they are hellish. One mother came to me and wanted a portrait of her daughter. She looked a nice kid and I didn’t charge very much. She wore jeans, but when she turned up she was all dressed up – it was awful!”

“I used to give them their drawings. They used to beg me for them and were so persuasive that I used to hand them over, until one day a boy took my drawing and folded it up in half and put it in his pocket. I nearly screamed! They never did that in Italy, they treasure their drawings there.”

“This is Harry. Miss Parry, the head teacher, she adored this drawing. Harry was really thick and he used to look at you with that blank expression, but he was marvellously funny and he made a tremendous effort. Somebody who used to work with me said, ‘I’m going to bring Harry to Miss Parry’s funeral,’ and I said, ‘But he’ll be middle aged now.’ She found him and he came to the funeral. I couldn’t believe it. He was a lorry driver for Charringtons.”

“This was a little Afghan girl, I thought she was beautiful. She was a vain little girl who would sit for hours in the art room. Miss Parry thought it was better for pupils to sit with me than to sit and do nothing, so she would send the badly behaved ones to the art room and I would draw them. They liked being drawn, they were flattered by it.”

“I never had any absentees from my art classes, they were always very keen. As my head teacher used to say, ‘They’ll always go to art with you!’ They enjoyed doing it. There were always a certain number who could not draw, who found it very difficult. I would get them started making patterns but they would think they could not do that. So I would say, ‘Yes you can.’ I would get something like an electric light bulb and say, ‘Make some patterns from what you can see with that.’ – repeating and so forth. And they would come up with some marvellous things. Then they got keen. You have to think up strange things to get children really interested.”

“This little girl, I got to know her mother and father, and she went on to grammar school. The children of immigrants always did much better than the English ones because their parents wanted them to work.”

“This was in the doctor’s waiting room. Quite a well known doctor round here invited me to draw there.”

Pictures courtesy of Dorothy Rendell Collection at Bishopsgate Insititute

You may also like to read about

John James Baddeley, Engraver, Die Sinker & Lord Mayor

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

“I haven’t time in my life for much else than work”

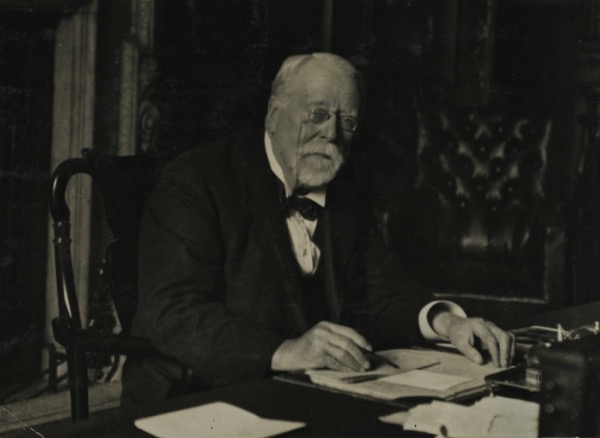

One hundred years ago this week, John James Baddeley, an engraver and die sinker, became Lord Mayor of London. Today his company, Baddeley Brothers, still flourishes as the pre-eminent specialist printers and envelope makers.

These photographs show Sir John James Baddeley, Baronet – known colloquially as ‘JJ’ – taking a Sunday morning walk with his wife through the empty City of London in 1922, when he was Lord Mayor and residing at the Mansion House.

With his top hat, cane and Edwardian beard, the eighty-year-old gentleman looks the epitome of self-confident respectability and worldly success, yet there is a poignancy in his excursion through the deserted streets, when the hubbub of the week was stilled, pausing to gaze into the windows of the shabby little printshops that competed to supply letterheads and engraved stationery to the banks, stock-brokers and insurance companies of the City.

In those days, all transactions and share issues required elaborately-engraved forms and there was a legal obligation to list all the directors on business notepaper which needed constant reprinting and adjustment of the dies whenever there were staff changes. Consequently, the City of London teemed with small highly-specialised companies eager to fulfil the constant demand for all this printed paper.

At the time of these photographs, nearly sixty years had passed since, at the age of twenty-three in October 1865, JJ had set up independently as a die sinker in a shared workshop in Little Bell Alley at the back of the Bank of England under entirely inauspicious circumstances. The eldest of thirteen children, JJ had already acquired plenty of experience of the long hours of labour required to scrape a modest living in the trade of die-sinking and engraving when he was apprenticed to his father at fourteen years old in Hackney.

Even by the standards of nineteenth century fiction, it was an extraordinary story of personal advancement. JJ oversaw the transformation of his business from an artisan trade to an industrialised process employing hundreds in a single factory. Born into an ever-increasing family that struggled to keep themselves, he inherited a powerful work ethos and a burning desire to overcome the injustice his father had suffered. JJ can only have been a driven man, the eldest brother who set his own modest industry in motion and then drew in his younger siblings to assist with spectacular results.

“In January 1857, I started my business life with my father in his workshop in Hackney at the back of the house at the Triangle in Mare St where I first donned a white apron, turned up my shirt sleeves and did all sorts of jobs,” he wrote of his apprenticeship in the trade of die sinking, “sweeping up and lighting the forge fire, warming the dies and later forging them on the anvil, then annealing them and afterwards filing them to shape and, when engraved, hardening them and tempering them.”

“During the whole time there, I was the errand boy, taking the dies and stamps to the few customers that my father had, Jarrett at No 3 Poulty being the chief one,” he recalled at the end of his life, “Many a time have I trudged – in winter with my feet crippled with chilblains – to the Poultry and at night to his other shop in Regent St. During the time I was at work with my father I had very good health, but we were all poorly-clad and none of the children had overcoats.”

In 1851, Griffith Jarrett exhibited his popular embossing press at the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, ordering the dies from JJ’s father who took on a larger house for his growing family and more apprentices on the basis of this seemingly-endless new source of income. Yet Griffith Jarrett exploited the situation mercilessly, inducing JJ’s father to make dies for him alone, then driving the prices down and eventually turning JJ’s father into a mere journeyman who worked like a slave and found he had little left after he had paid his production costs, impoverishing the family.

When, as a boy, JJ walked through the snow at night to deliver the dies for his father to Griffith Jarrett’s Regent St shop at 8pm or 10pm, Jarrett sometimes gave JJ tuppence to ride part of the way home. It was an offence of meagre omission that JJ never forgot. “These two pennies were the beginnings of my savings which enabled me to set up in business for myself and to defy the man who for more than twenty years had my father in his clutches,” admitted JJ in later years.

“I began work by doing simple dies for my father at journeyman prices and began making traces, stops, commas, letter punches and other small tools. By the end of the year, I managed to get a few orders for dies from Messrs John Simmons & Sons who had a warehouse in Norton Folgate,” he recorded, looking back on his small beginnings in the light of his big success, “I turned out my work quicker than my competitors and gave better personal attention to my customers, trusting to this rather than obtaining orders by quoting lower prices.”

“These were very strenuous and hard working times, I commenced work at nine and seldom leaving before ten o’clock at night,” he confessed – but twenty years later, in 1885, the company occupied a six storey factory at the corner of Moor Lane and employed more than three hundred people. It was an astonishing outcome.

Yet, while embracing the potential of technological progress so effectively, JJ possessed an equal passion for craft and tradition – especially the history of Cripplegate where he became a Warden. “In 1889, an attempt to take down the St Giles Church Tower, after a good fight I saved it,” he wrote with succint satisfaction. Later, devoting a year of his life to writing an authoritative history of Cripplegate, he prefaced it with the words – “Let us never live where there is nothing ancient, nothing to connect us with our forefathers.”

No wonder then that, as an old man, John James Baddeley chose to stroll through the empty streets of London on Sunday mornings, pausing to look into old print shop windows, and consider his own place in the long history of printing and the City.

John James Baddeley’s business card

Over 300 hands were employed at Baddeley Brothers in Moor Lane, 1888

Engineering & Press Making Dept in the basement

Paper & Envelope Department on the first floor where over fifty hands are employed in envelope making, gumming, black and silver bordering, scoring etc

Die Sinking & Engraving Dept – The largest in the trade, twenty-one die sinkers are employed alongside twenty-one copperplate engravers and eight wood engravers.

Litho Dept on the second floor with fourteen copperplate presses, three litho machines, nine litho presses and three Waddie lithos

The view from the Mansion House in 1922

JJ in the Venetian Parlour at the Mansion House

You may also like to read about