Wonderful London’s East End

JOIN ME FOR FOR A WALK THROUGH 2000 YEARS OF HISTORY IN SPITALFIELDS THIS EASTER

READ THE EMBARRASSINGLY GOOD REVIEWS

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR SPRING & SUMMER TOURS

It is my pleasure to publish these evocative pictures of the East End (with some occasionally facetious original captions) selected from the popular magazine Wonderful London edited by St John Adcock and produced by The Fleetway House in the nineteen-twenties. Most photographers were not credited – though many were distinguished talents of the day, including East End photographer William Whiffin (1879-1957).

Boys are often seen without boots or stockings, and football barefoot under such conditions has grave risks from glass or old tin cans, but there are many urchins who would rather run about barefoot.

When this narrow little dwelling in St John’s Hill, Shadwell, was first built in 1753, its inhabitants could walk in a few minutes to the meadows round Stepney or, venture further afield, to hear the cuckoo in the orchards of Poplar.

Middlesex St is still known by its old name of Petticoat Lane. Some of the goods on offer at amazingly low prices on a Sunday morning are not above suspicion of being stolen, and you may buy a watch at one end of the street and see it for sale again by the time you reach reach the other.

A vanished theatre on the borders of Hoxton, just before demolition, photographed by William Whiffin. In 1838, a tea garden by the name of ‘the Eagle Tavern’ was put up in Shepherdess Walk in the City Rd near the ‘Shepherd & Shepherdess,’ a similar establishment founded at the beginning of the same century. Melodramas such as ‘The Lights ‘O London’ and entertainments like ‘The Secrets of the Harem,’ were also given. In 1882, General Booth turned the place into a Meeting Hall for his Salvation Army. There is little suggestion of the pastoral about Shepherdess Walk now.

In the East End and all over the poorer parts of London, a strange kind of establishment, half booth, half shop, is common and particularly popular with greengrocers. Old packing cases are the foundation of a slope of fruit which begins unpleasantly near the level of the pavement and ends in the recess behind the dingy awning. At night, the buttresses of vegetables are withdrawn into shelter.

Old shop front in Bow photographed by William Whiffin. Pawnbroking, once as decorous as banking, has fallen from the high estate in the vicinity of Lombard St. Now, combined instead with the sale of secondhand jewellery, furniture and hundred other commodities, it is apt to seek the corners of the meaner streets.

A water tank covered by a plank in a backyard among the slums is an unlikely place for a stage, but an undaunted admirer of that great Cockney humorist, Charlie Chaplin, is holding his audience with an imitation of the well-known gestures with which the famous comic actor indicates the care-free-though-down-and-out view of life which he has immortalised.

Old shop front in Poplar photographed by William Whiffin

An old charity school for girl and boy down at Wapping founded in 1704. The present building dates from 1760 and the school is supported by voluntary subscriptions. The school provided for the ‘putting out of apprentices’ and for clothing the pupils.

The hunt for bargains in Shoreditch. A glamour surrounds the rickety coster’s barrow which supports a few dozens of books. But, to tell the truth, the organisation of the big shops is now so efficient that the chances of finding anything good at these open air book markets may have long odds laid against it.

The landsman’s conception of a sailing vessel, with all its complex of standing and running rigging that serves mast and sail with ordered efficiency, is apt for a shock when he sees a Thames barge by a dockside. The endless coils and loops of rope of different thickness, the length of chain and the litter of brooms, buckets, fenders and pieces of canvas, seem to be in the most insuperable confusion.

Gloom and grime in Chinatown. Pennyfields runs from West India Dock Rd to Poplar High St. A Chinese restaurant on the corner and a few Chinese and European clothes are all that is to be seen in the daytime.

The gem of Cornhill, Birches, where it stood for two hundred years. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the brothers Adam erected its beautiful shop front. Within were old bills of fare printed on satin, a silver tureen fashioned to the likeness of a turtle and many other curious odd-flavoured things. Birches have catered for the inspired feasting of the City Companies and Guilds for two centuries but now this shop has moved to Old Broad St and, instead of Adam, we are to have Art Nouveau ferro-concrete.

It is doubtful if the Borough Council of Poplar had any notion, when they supplied the district with water carts, that the supplementary use pictured in this photograph by William Whiffin would be made of them. Given a complacent driver, there is no reason why these children should not go on for miles.

Grime and gloom in St George’s St photographed by William Whiffin. St George’s St used to be the famous Ratcliff Highway and runs from East Smithfield to Shadwell High St. It is a maritime street and contains various establishments, religious and otherwise, which cater for the sailor.

River Lea at Bow Bridge photographed by William Whiffin. On the right are Bow flour mills, while to the left, beyond the bridge, a large brewery is seen.

A view of Curtain Rd photographed by William Whiffin, famed for its cabinet makers. It runs from Worship St – a turning to the left when walking along Norton Folgate towards Shoreditch High St – to Old St. Curtain Rd got its name from a curtain wall, once part of the outworks of the city’s fortifications.

Fish porters of Billingsgate gathered around consignments lately arrived from the coast. At one time, smacks brought all the fish sold in the market and were unloaded at Billingsgate Wharf, said to be the oldest in London.

Crosby Hall as it stood in Bishopsgate. Alderman Sir John Crosby, a wealthy grocer, got the lease of some ground off Bishopsgate in 1466 from Alice Ashfield, Prioress of St Helen’s, at a rent of eleven pounds, six shillings and eightpence per annum, and built Crosby Hall there. It came into the possession of Sir Thomas More around 1518 and by 1638 it was in the hands of the East India Company, but in 1910 it was taken down and re-erected in Cheyne Walk.

Whatever their relations with the Constable may come to be in later life, the children of the East End, in their early days, are quite willing to use his protection at wide street crossings.

There is no more important work in the great cities than the amelioration of the slum child’s lot. Many East End children have never been beyond their own disease-ridden courts and dingy streets that form their playground.

Photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Susannah Dalbiac’s Almanack

JOIN ME FOR FOR A WALK THROUGH 2000 YEARS OF HISTORY IN SPITALFIELDS THIS EASTER

READ THE EMBARRASSINGLY GOOD REVIEWS

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR SPRING & SUMMER TOURS

Margaret Nairne brought her great-great-great-great-aunt’s diary to show me. It is an Almanack of 1776 belonging to fourteen-year-old Susannah Dalbiac, whose father Charles Dalbiac was a silk & velvet merchant who ran the family business with his brother James at 20 Spital Sq. The Dalbiacs were Huguenots and Susannah’s grandfather escaped France as a youth in a hamper in July 1681 after his parents and three sisters were murdered. At the opening of the diary in January 1776, London was suffering a Great Frost with temperatures as low as minus eighteen degrees. (You can click on any diary page to enlarge it)

Monday JANUARY 1st 1776

Mama & Lucy drank tea at Mrs Martin’s. I stayed at home to make tea for Papa and Cousin James

Tuesday

Papa & Cousin James Dalbiac went to Town before Dinner.

Wednesday

Mama went to Town in the Coach at nine o’clock, took Harriet & Nurse with her. The man came to take down the Organ.

Thursday

We worked at our muffs, drew and did the same as when Mama is at home.

Friday

The man finished packing up the organ. We finished our muffs.

Saturday

I was very glad to see Papa and Mama. They came to dinner. Mama was so good as to make a present of a fan and an Almanack.

Sunday

We did not go to Church. We read a sermon in the morning… The text was Felix’s behaviours towards Paul explained.

Monday JANUARY 15th

Mr Cooke call’d in the morning. They play’d at Quadrille in the evening.

Tuesday

Papa went to town. Mama read Cyrus in the evening.

Wednesday

At Home alone.

Thursday

Mama read Cyrus in the evening.

Friday

Papa came down to dinner. They play’d at Quadrille in the evening.

Saturday

Papa took a ride in the morning to Admiral Geary’s. They play’s at Quadrille in the evening.

Sunday

We read a sermon in the morning, the text was National Mercies considered. I wrote what I understood by it. I kept up a hundred at Battledore Shuttlecock with Miss Watson.

Monday MARCH 11th

Went to Town. Took CM. Din’d at GM’s. Came back to tea. Mama drank tea at Mr Sebly’s. We at home with CM. Papa went to Bookham.

Tuesday

CKL & CM drank tea here. DK slept here.

Wednesday

Papa came to tea. Sally & Frank came to dinner from Bookham.

Thursday

Papa went to Town. We took a ride with Mama & Aunt L to Hackney. Papa came to Dinner.

Friday

Mama took a ride in the Phaeton with Papa.

Saturday

Papa went to Town. Came back to dinner, Papa went to Mr Paris’s. At home with Mama, Lucy and CM.

Sunday

Went to church with CL & we din’d here Papa & Mama drank tea at Uncle Lamotte’s.

(Susannah mistakenly entered her grandmother’s death on the wrong date and crossed it out)

Monday APRIL 1st

Aunt Lamotte went to town with Papa. Came back to tea. They all came in the evening. Grandmama very ill.

Tuesday

Papa went to town. Took CM with him. Came back to tea.

Wednesday

Aunt & Uncle Lamotte went to town with Papa. Aunt and Uncle came back to tea. We spent the day with Mama at Uncle Lamotte’s.

Miss Louise Delaporte

Thursday

Aunt & CL went to town with Papa. Aunt & Uncle came back to tea. We spent the day with Mama at Uncle Lamotte’s.

Grandmama died at four in the evening. Though expected at her age it is always a great loss. She was 84 next July

Friday

Aunt and CL went to Town Came back to dinner with Papa. They spent the evening here. CM came in the morning.

Friday

Papa went to town. Came back to tea. Mama drank tea at Uncle Lamotte’s. CM came here.

Saturday

Went to town with Papa, Uncle and Aunt L & CL who was so good as bespeak some mourning for us, Mama not being well enough. Saw G’mama. Did not find her much alter’d.

Sunday

CL came in the morning. We drank tea at Uncle Lamotte’s. Papa came down in the evening.

Monday APRIL 22nd

Drank tea at Uncle Lamotte’s where we met Uncle Dalbiac’s family

Tuesday

CK call’d. Papa slept in town

Wednesday

Papa came to dinner. Mr Paul and Peter L [..?] spent the day here

Thursday

CM spent the day here. CK called

Friday

Papa went to town. We spent the day at Uncle Lamotte’s

Saturday

CK call’d in the afternoon with MJ Lamotte.

Sunday

Went to church with CK. Sukey din’d here. CM came in the morning.

(Susannah’s own mother had died young and her stepmother gave birth to a baby boy in April.)

Monday APRIL 29th

Mama rather low at little boys going out to nurse. We drank at Uncle. Aunt came here to tea and CL in the evening. Note on opposite page – The little boy went out to nurse upon the Forest the nurse not being able to come.

Tuesday

Papa went to town

Wednesday MAY 1st

Went with nurse Flaxman to see the little boy. Found him very well

Thursday

Staid at home. Aunt Ch CS Dalbiac drank tea here

Friday

Went with nurse Flaxman to see the little boy

Saturday

Papa went to Uncle Lamotte’s in the evening where he met a great many people

Sunday

Went to church with CKL. After church we went with CM to fetch little boy. She spent the day with us.

Monday MAY 13th

Sir John Silvester came to see mama, she was so very low. CK call’d

Tuesday

Sir John Silvester came. Papa went to town came back at night

Wednesday

Papa went to town. Came back for tea.

Thursday

Sir John Silvester came

Friday

Papa went, came to back to tea. Took a ride after tea to see little boy. Found him very well. Call’d on Uncle Lamotte

Saturday

Sir John Silvester came. Ordered mama today a bed till Monday as had a little rash. CM drank tea here.

Sunday

There was no service. Took a ride with Papa & Aunt Lamotte. Called at Uncle Dalbiac.

(Sir John Silvester was a doctor from the French Hospital and one of the top physicians of the day)

(Susannah records her winnings at Quadrille on the right hand page)

Monday JUNE 10th

We drank tea at Mrs Brickendon’s with Mr and Mrs B and C. Walles. Met Mr ? and Mr Forbes

Tuesday

At Home. Play’d at Quadrille in the evening

Wednesday

Mr and Mrs Jourdan came down to dinner. Mrs Fellen and Mrs Draper dined here. Played at Piquet with Mr Barbut.

Thursday

Mrs Brickendon and Miss Streton drank tea here.

Friday

Drank tea at Mrs Brickendon. Lucy played at cards after they came home. Went halfs with her.

Saturday

Drank tea at Mrs Fellen’s. Mr Barbut came down in the Phaeton

Sunday

Went to Church with Miss Barbut. Mrs Rose & Mrs Forbes. Drank tea here.

Monday JUNE 24th

Spent the day at Uncle Lamotte’s. Slept there. Left Wanstead Lane.

Tuesday

In the Morning Papa tooke with the Phaeton to Uncle Dalbiac’s. Took a walk in the evening to see Harriet with Aunt.

Wednesday

At home alone.

Thursday

Spent the day at Sir J Silvester’s with Aunt & Uncle, CL & CM. We had a very agreeable day.

Friday

At home all day

Saturday

We went with Aunt in the morning to see little boy. Found him very well at 1 0’clock Mr Gallie called in the coach. We went with him to Uncle Lamotte’s

Monday JULY 1st

The coach came for us after Dinner to go to Town. Found Mama very well which made me quite happy

Tuesday

Went with mama the other end of Town in the morning. Very busy all day.

Wednesday

We all went down to Uncle Lamotte’s in the evening.

Thursday

Went to Town in the morning. CL & CM with us. We all went to Vauxhall in the evening & I found it much greater than my expectations as I had never see it before. In the morning we saw little Harriet and little boy.

Friday

Very busy all day. Mr Laport din’d with us. He came from New Providence to see Grandmama his sister but was disappointed.

Saturday

We set out a journey…

There is a gap in Susannah Dalbiac’s diary between 6th July and 14th October, after which she is in Paris and from then on many of the entries are written in French. It may be that her stepmother’s illness led the family to return to France where she had relatives or that the turbulence of the Weavers’ Riots in Spitalfields at this time caused James Dalbiac to withdraw his business. Susannah never married or had children but, living with her sister Louisa, she died at her brother-in-law Peter Luard’s house, Blyborough Hall, Lincolnshire in 1842, aged eighty.

Follow Margaret Nairne’s blog www.huguenotgirl.com

You may also like to take a look at

New Consultation For The Chest Hospital

JOIN ME FOR FOR A WALK THROUGH SPITALFIELDS THIS GOOD FRIDAY, EASTER SATURDAY OR EASTER MONDAY

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR SPRING & SUMMER TOURS

The Bethnal Green Mulberry, September 2022

Long-standing readers may recall how I once visited the palatial Victorian London Chest Hospital next to Victoria Park as a patient to have the capacity of my lungs measured when recovering from pneumonia. On a return visit, upon the day the hospital was shut down and sold off for redevelopment, I was introduced to the historic Bethnal Green Mulberry planted by Bishop Bonner in 1540 and the oldest tree in the East End.

After a five year campaign, under the patronage of Dame Judi Dench and with the magnificent support of you, the readers of Spitalfields Life, we stopped developers Crest Nicholson digging up this tree and proceeding with their overblown proposal which offered too small a proportion of affordable housing and retained too little of the existing buildings.

Defeated, they sold off the site to Latimer Homes (part of Clarion Housing Group) who committed publicly to ‘retaining the mulberry tree in its current location’ and ‘providing more genuinely affordable homes that meet local need.’ This was a result and now we must hold them to it.

The new development proposal for the London Chest Hospital site is to be revealed next week at public consultation on Wednesday 22nd March 6pm-8pm and Saturday 25th March 11am-2pm at Bethnal Green Methodist Church Approach Rd, E2 9JP. Readers are encouraged to attend.

Last September, Clarion Housing Group invited me to pay a visit to the Bethnal Green Mulberry, now protected by a ring of fencing with a sign declaring ‘Tree protection area. Keep out!’ and under the supervision of a designated arborculturalist. It was an emotional moment to encounter the old tree again, years since I first saw it and after so much grief expended to save it.

Laudably, the developers now declare a commitment to ‘Create the most sustainable scheme possible.’

Walking around the site, it was obvious that several buildings are of significant quality, even beyond the listed main hospital building. In particular, I was struck by the handsome Edwardian terrace of nurses dwellings at the rear of the hospital which would only take refurbishment to be put back into use as flats for single people. Yet it was indicated to me that this is likely to be demolished, even though it is obvious that the ‘greenest’ building is one which already exists. So I think the imperative now is to maximise the repurposing of the extant buildings.

These handsome Edwardian nurses’ dwellings could be refurbished as flats for single people but instead are likely to be demolished.

Terrace of nurses’ dwellings at the London Chest Hospital

A NOTE ABOUT MULBERRY CUTTINGS

Those who contributed £100 or more to our fighting fund to save the Bethnal Green Mulberry in 2020, were eligible to saplings grown as cuttings from a scion of a Mulberry planted by William Shakespeare. Unfortunately, the cuttings we took in 2021 failed due to a fungal infection that affected the tree then. Now the tree has recovered, we are going to try again this spring and we will keep you posted.

Read more about the Bethnal Green Mulberry

The Bethnal Green Mulberry Verdict

The Fate of the Bethnal Green Mulberry

At Margolis Silver

JOIN ME FOR FOR A WALK THROUGH SPITALFIELDS THIS GOOD FRIDAY, EASTER SATURDAY OR EASTER MONDAY

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR SPRING & SUMMER TOURS

Kudret Yirtici, Polisher

There are still traditional manufacturing industries thriving in the East End – as Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I were delighted to discover when we visited Margolis Silver, market-leaders in silverware, at their factory in London Fields. Here we found a band of highly-skilled silversmiths with proud dirty faces, designing and manufacturing silverware for the swankiest West End hotels, restaurants and clubs, employing techniques that have not changed in centuries.

Upstairs in his solitary garret, we met the most senior member of staff, Albert Alot, a virtuoso metal spinner of a lifetime’s experience who can take a disc of copper and expertly spin it into a cup on a lathe with all the flamboyant magic of Rumplestiltskin. Down below, led by Richard Courcha whose father started the company half a century ago, we found the polishers at work, cleaning the copper vessels prior to plating. With their grimy visages and overalls topped off by a characterful array of hats, they were a charismatic band who generously welcomed us into their lair and tolerated our nosy questions with patience and good humour. Next door, Chloe Robertson supervised the electroplating, first with nickel and then silver, cheerfully presiding over two enormous boiling vats of steaming hydrochloric acid and livid green arsenic bubbling away.

There is a compelling alchemy to this fascinating process which, thanks to immense skills of the silversmiths, transforms the raw material of copper sheets into sophisticated gleaming silverware, sufficient to grace the grandest tables with its luxurious allure. It is exceptional to visit a workshop such as this, where everyone takes such obvious delight in their collective achievement.

Away from the workshop, Valerie Lucas runs an office stacked to the roof with myriad examples of silverware, teapots, coffeepots, condiments, basins, bowls and plates of every imaginable design. Here we met director Lawrence Perovetz, who is of Huguenot descent and cherishes the living tradition of Huguenot silversmiths in London through his work.

Yet all these people, machines and processes are crammed into a tiny factory that few in London Fields even know exists. As Polisher Pascal Fernandes quipped, summing it up succinctly for me, “It’s a little house of treasures this is!”

Arthur Alot – “I’m from Plaistow and I was born in the war. I’ve been doing this all my life, since I did an apprenticeship down at Shaw’s Metal Spinners in Stratford years and years ago. They’ve gone now. Years ago in the twenties, the old spinners used to walk in dressed in spats and whatever. I moved to a factory in the Holloway Rd where I met this spinner, a proper one, who had come out of Hungary at the time of the revolution. He had been taught by the sixth best spinner in Hungary and he taught me and my brothers. I have taught a few who are starting on their own.”

Arthur spins a cup out of a disc of copper

Arthur Alot, Metal Spinner

Richard Courcha – “I am the factory manager and I do polishing. It was my father, Thomas Courcha’s business, he started it in 1968. He was a metal polisher and he went into partnership with Johnny Mansfield in a little factory in North London and then, when this place came up for grabs in 1968, they moved in. The company was called TC Plating Ltd – Tommy Courcha Plating in full.

I came here all the time as child, every other Saturday in the back of my dad’s old red Escort van. It was a bustling place. I used to help out with the makers, there were ten makers working here during the late seventies. In those days we manufactured for the retail market, producing gallery trays, punchbowls and wine coolers that were sold in the West End. Designers would bring in their drawings, and my dad and his team would make the moulds and conjure them up.

The retail side dropped off in the eighties because of cheap products coming in from India. So then we moved into restoring antique silverware. About ten years ago, it all changed again. This was around the time I met Lawrence who had this idea of supplying hotels and now we are joined at the hip.

I came here to work in 1982. I did not have any plans to do anything else. It was a bustling business and my brother was here as well until he retired. I suppose I like the job. It is what I do. It is in my blood. It is what I grew up with. After thirty-six years, I know how to do making.”

Collin Foru-berkoh, Polisher

Bradley Hitchman – “I am a silversmith and maker of thirty-four years. When I was thirteen, I moved to Morden and the next door neighbour owned this company. A few years after I left school, I was doing a training scheme to be an engineer but I thought ‘Silversmith’ sounded more glamorous than ‘Engineer.’ So I came here. It was a struggle at first. It was very repetitive, hundreds of this, thousands of that. The same thing over and over again. But when it comes to doing it now it is second nature. Once I got the hang of things and things came easier, it was no longer boring – you just got on with it. I have always liked working with my hands. I like the creative side of this work, you can take a piece of metal and turn it into something – like this dessert trolley! Pretty much everything here is bespoke. ”

Pascal Fernandes – “I am a polisher and a finisher. Way back in 1976, I got an apprenticeship as a polisher and I was taught by three very good people. It is very dangerous work because the machines show you no mercy, they can take your hand off. At first, I found it boring but over the years you learn from other people who might do something differently. You do not necessarily copy them because each has an art of their own. My way is the way I was taught originally by a man who was taught by the best. It is creative and I took it as my living, so I must like it. You learn your lessons as you go along. You have got to take the good with the bad.”

Chloe Robertson – “I am a maker and I do electroplating as well. I did a degree in Design in Liverpool and picked working with metal and wood. I won ten thousand pounds start-up business funding and I funded myself to go to Bishopsland which is a post-graduate college for silversmiths and jewellers, and then I won an award as ‘Woodturner of the Year’ which meant I got a free workshop for a year. Then this job popped up and I have been here two years. I am the newbie, but I love this work and I intend to stay at least ten years. It is fascinating working alongside these guys who have been here for all these years, I learn something new every day. Some of these techniques they know are mind-boggling.”

Chloe plates the copper with nickel in a vat of boiling arsenic

Chloe dries the plated objects in a box of grain

Lawrence Perovetz, Director & Valerie Lucas, Secretary, Margolis Silver

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to look at these nearby manufacturers

Sheila Bell Remembers Great Eastern Buildings

JOIN ME FOR FOR A WALK THROUGH SPITALFIELDS THIS GOOD FRIDAY, EASTER SATURDAY OR EASTER MONDAY

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR SPRING & SUMMER TOURS

(Click on this photograph to enlarge it)

Can you spot Sheila Bell in this photograph of the residents of Great Eastern Buildings celebrating Victory in Europe Day at the Grey Eagle in Quaker St on 2nd May 1945? Look more closely, there she is sitting in the front row, to the left of the girl in a floppy hat. Sheila has a bow in her hair for this special occasion.

Unfortunately, this picture was not too much use when I met Sheila at Victoria Station recently to hear about her life at Great Eastern Buildings on the corner of Brick Lane and Quaker St. Yet, as Sheila began to tell her story, I quickly recognised the little girl in this photograph of a lifetime ago.

“My grandparents, George & Sarah Keppel, lived in Great Eastern Buildings and my great-grandparents, Emma & Frederic Lewis lived in the same flat before them – before that I do not know. My nan never went out to work, she stayed at home, cooked the dinner and kept the house, and my granddad worked down Spitalfields Market. He started off as a porter but he was a carpenter by trade, so he made the ladders for the guys in the market. He hired two rooms in the next block at the Buildings and did all his carpentry work there. I used walk in there and smell the fresh wood shavings. He had a black iron glue pot and he made me stir it. It looked like toffee but it did not smell like toffee, I can assure you.

My parents lived in the Buildings as well and, as soon as I was born, I was taken to the Buildings, as the fourth generation of my family there. My mother worked in Truman’s Brewery as a bottling girl, she wore a green overall, a white apron and clogs, and my father was a smoked salmon curer in Frying Pan Alley, opposite Liverpool St Station. We lived in flat number sixty-eight Great Eastern Buildings, on the second floor. I was brought up in those Buildings with Jewish, Irish and Maltese, and we all rubbed along very nicely.

There always used to be a lot of workmen in and out of the Buildings, fixing things, and my first memory was of playing with a load of sand and water. Me and my cousins used to make sandcastles in the builders’ sand. That was our life! We lived in two rooms. We shared a wash house with a mangle and three sinks, two normal-sized and one butler’s sink with two taps. There was no hot water and each of the four flats on the landing shared the wash house. If you wanted a bath you had to boil a kettle. We had a tin bath like everybody else and an outside toilet that we shared with the three other families. We took it in turns to clean the toilet on a weekly rota system.

I do not remember a gas stove but I do remember a black range. You could lift the lid with a poker and put coal in. The kettle was always on the hob and there was an oven to the side. On Sunday, my nan would black-lead the range and it used to gleam. It had a white hearth and she used to whiten it, that was her pride and joy. It was always done, and our two rooms were kept clean. One room doubled as a front-room-come-kitchen, -come-everything really. We had old armchairs in there and a settee made of Rexine, that looked like leather but it was plastic and, in the summer, it used to stick to your legs, so we had to put a blanket on it. We had an old piano, I think everybody in those days had a piano. There was a little sink in the corner for the bowl and jug which we kept in the bedroom. That was all you had plus a table and a cupboard.

In the bedroom, we had a double bed and a single bed, if you had more than one child or if anybody came to stay. Unfortunately, that was how it was. We put up with because we did not know any different. I was the eldest and I had a younger brother. Now my nan had two rooms and my mum had two rooms, so my brother slept in the front room which meant mum and dad had the bedroom, my nan and grandad had the other bedroom and I slept in the other front room on a made-up bed. I used to lie on the floor and listen to the trains shunting in the goodsyard. Both flats were opposite each other across the same landing.

When I was fourteen, the flats were modernised by combining two, so then we had two bedrooms, a kitchen and a lounge. They put in electricity. It was amazing because I had only known gaslight since childhood. We did not know we were born! It was like a palace. I had my own room and my brother had his own room. It was our home and they did not move us out while they modernised, they just worked around us.

As children, we used to love to run through Wheler St Arch because it was always dark and gloomy with gas lamps – it was a dare really. We liked to go down Spitalfields Market and pick up the specks – the damaged fruit – and we used to bring them home. We did not have any other fruit. At Christmas time, my granddad came home with a sack full of specks. All the family would get together round the piano. My Auntie used to play the piano fantastically, sitting on a crate of brown ale. My nan never went out all week but on a Saturday night she went with out her friend and they would go either to the Two Brewers on the corner or the Grey Eagle. On a Saturday night, when she did not go out, my nan and I, we would get our pillow and put it on the window sill, and sit with our cups of tea and wait for the pubs to turn out. There would be fights and it was entertainment for us.

My granddad used to have a stall at the top of Brick Lane on Sundays and sell nuts and bolts, and I took tea to him in a white enamel flask. The market was packed in those days and, by the time I got there, the tea would be splashed everywhere, so he only got one cup out of it.

My first job was for Durrants the printers opposite Mount Pleasant Post Office in Clerkenwell and I absolutely hated it. I was sixteen or seventeen and I used to come home black with ink. Then I went into the rag trade, machining at Universal Underwear – it was very highbrow, we made it for Marks & Spencers – just off Shoreditch High St. I loved it and stayed there for ten years. I did an apprenticeship and my first week’s pay was four pounds, nineteen shillings and eleven pence. I thought I was rich!

After three months, they put you on piecework and I used to earn a fortune. Twenty or thirty pounds a week was a lot of money in those days. I was a saver and there would be times when I only had a shilling and sixpence in my purse but that was fine. I have always put a bit by because you never know what might happen. My parents did the same and they taught me not to spend money on non-essentials. Then, if you really need that money you do not have to go to anybody, you have got it there. My mother was very independent and my parents never owed anybody any money. I only ever wanted to pay the rent and put food on the table.

When I was twenty-five, I left Great Eastern Buildings to get married. I met my husband Riaz at Queen’s Ice Skating Rink in Bayswater. It was a ritual, I used to go there every Friday. Every Saturday, we went to the cinema and, every Sunday, we went to the Mecca Ballroom in Leicester Sq. We had a fantastic social life. We moved to a rented two bedroom flat in Hackney Downs when we got married and my daughter was born in Lower Clapton Rd at the Salvation Army Hospital. My husband was an aircraft engineer at Gatwick and the travelling was too much for him, so they offered us a flat down there and we stayed thirty years.

I still miss the community spirit of Great Eastern Buildings. Nobody went without, the people in those Buildings would give you their last ha’penny even if they had nothing.”

The Grey Eagle photographed by Philip Marriage in 1967

Corner of Grey Eagle St today

Steven Harris, who also grew up in Great Eastern Buildings, managed to identify these people:

Little girl at front, right of centre, with floppy white hat is Joyce Gibbons (my Aunty Joyce).

Next to floppy white hat, toddler with bow in hair is Sheila Bell herself.

The lady to the left, with her arm up, may well be Franny Vigas.

Behind Franny, with the dark hair is Sarah Keppel (Sheila’s grandmother)

The shorter of the two men, just to Sarah’s right, is Sheila’s granddad, George Keppel.

To George’s right, with her back against the pub wall is Lily Bell (Sheila’s mother)

Further to the right, holding two children (you can just see her head against the pub window) is Bessie Lee, sister to Lily Bell. The two children were Lorraine and Ronnie Lee.

Staying at the back and just along from Bessie Lee and her children, are two dark haired women – they were sisters, Celia and Sarah Bawes.

One forward and three along to the right from Lily Bell is a blond girl with roundish face – that was Betty Wright (who was long standing friends with my Aunty Pat)

Third row back, a little to the left of the roll of honour, with her beret pulled down at a sharp angle and standing slightly alone, is Phyllis Greenslade.

To the extreme right of the photo, sitting next to the honours roll, is Pat Green.

Third row back, to the left of the central line of children, is George Hall (with finger in mouth).

To the left of George is, I believe, my very own nine-year-old dad – Eddie Harris!

George’s sister, Rosie, is the blond girl with big smile, one row forward and three along to the right of George.

Sheila Butt (nee Bell)

You may also like to read about

Booker T. Washington In Petticoat Lane

JOIN ME FOR FOR A WALK THROUGH SPITALFIELDS THIS EASTER!

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR SPRING & SUMMER TOURS

Portrait by Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1895

Spokesman and leader of African American people in the USA, Booker T. Washington came to London in 1910 to study the living conditions of the poor on this side of the Atlantic by comparison with his own country. On arrival in London, his first destination was Petticoat Lane Market, as he described in his book The Man Farthest Down, The Struggle of European Toilers, written with the collaboration of sociologist Robert E. Park and published in 1912.

‘The first thing about London that impressed me was its size, the second was the wide division between the different elements in the population.

London is not only the largest city in the world, it is also the city in which the segregation of the classes has gone farthest. The West End, for example, is the home of the King and the Court. Here are the Houses of Parliament, Westminster Abbey, the British Museum, most of the historical monuments, the art galleries, and nearly everything that is interesting, refined, and beautiful in the lives of seven millions of people who make up the inhabitants of the city.

If you take a cab at Trafalgar Square, however, and ride eastward down the Strand through Fleet Street, where all the principal newspapers of London are published, past the Bank of England, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and the interesting sights and scenes of the older part of the city, you come, all of a sudden, into a very different region, the centre of which is the famous Whitechapel.

The difference between the East End and the West End of London is that East London has no monuments, no banks, no hotels, theatres, art galleries; no history – nothing that is interesting and attractive but its poverty and its problems. Everything else is drab and commonplace.

It is, however, a mistake, as I soon learned, to assume that East London is a slum. It is, in fact, a city by itself, and a very remarkable city, for it has, including what you may call its suburbs, East Ham and West Ham, a population of something over two millions, made up for the most part of hard-working, thrifty labouring people. It has its dark places, also, but I visited several parts of London during my stay in the city which were considerably worse in every respect than anything I saw in the East End.

Nevertheless, it is said that more than one hundred thousand of the people in this part of the city, in spite of all the efforts that have been made to help them, are living on the verge of starvation. So poor and so helpless are these people that it was, at one time, seriously proposed to separate them from the rest of the population and set them off in a city by themselves, where they could live and work entirely under the direction of the state. It was proposed to put this hundred thousand of the very poor under the direction and care of the state because they were not able to take care of themselves, and because it was declared that all the service which they rendered the community could be performed by the remaining portion of the population in their leisure moments, so that they were, in fact, not a help but a hindrance to the life of the city as a whole.

I got my first view of one of the characteristic sights of the East End life at Middlesex Street, or Petticoat Lane, as it was formerly called. Petticoat Lane is in the centre of the Jewish quarter, and on Sunday morning there is a famous market in this street. On both sides of the thoroughfare, running northward from Whitechapel Road until they lose themselves in some of the side streets, one sees a double line of pushcarts, upon which every imaginable sort of ware, from wedding rings to eels in jelly, is exposed for sale. On both sides of these carts and in the middle of the street a motley throng of bargain-hunters are pushing their way through the crowds, stopping to look over the curious wares in the carts or to listen to the shrill cries of some hawker selling painkiller or some other sort of magic cure-all.

Nearly all of the merchants are Jews, but the majority of their customers belong to the tribes of the Gentiles. Among others I noticed a class of professional customers. They were evidently artisans of some sort or other who had come to pick out from the goods exposed for sale a plane or a saw or some other sort of second-hand tool, there were others searching for useful bits of old iron, bolts, brass, springs, keys, and other things of that sort which they would be able to turn to some use in their trades.

I spent an hour or more wandering through this street and the neighbouring lane into which this petty pushcart traffic had overflowed. Secondhand clothing, secondhand household articles, the waste meats of the Saturday market, all kinds of worn-out and cast-off articles which had been fished out of the junk heaps of the city or thrust out of the regular channels of trade, find here a ready market.

I think that the thing which impressed me most was not the poverty, which was evident enough, but the sombre tone of the crowd and the whole proceeding. It was not a happy crowd, there were no bright colours, and very little laughter. It was an ill-dressed crowd, made up of people who had long been accustomed to live, as it were, at second-hand and in close relations with the pawnbroker.

In the Southern States it would be hard to find a coloured man who did not make some change in his appearance on Sunday. The Negro labourer is never so poor that he forgets to put on a clean collar or a bright necktie or something out of the ordinary out of respect for the Sabbath. In the midst of this busy, pushing throng it was hard for me to remember that I was in England and that it was Sunday. Somehow or other I had got a very different notion of the English Sabbath.

Petticoat Lane is in the midst of the “sweating” district, where most of the cheap clothing in London is made. Through windows and open doors I could see the pale faces of the garment-makers bent over their work. There is much furniture made in this region, also, I understand. Looking down into some of the cellars as I passed, I saw men working at the lathes. Down at the end of the street was a barroom, which was doing a rushing business. The law in London is, as I understand, that travellers may be served at a public bar on Sunday, but not others. To be a traveller, a bona-fide traveller, you must have come from a distance of at least three miles. There were a great many travellers in Petticoat Lane on the Sunday morning that I was there.

This same morning I visited Bethnal Green, another and a quite different quarter of the East End. There are a number of these different quarters of the East End, like Stepney, Poplar, St. George’s in the East, and so forth. Each of these has its peculiar type of population and its own peculiar conditions. Whitechapel is Jewish, St. George’s in the East is Jewish at one end and Irish at the other, but Bethnal Green is English. For nearly half a mile along Bethnal Green Road I found another Sunday market in full swing, and it was, if anything, louder and more picturesque than the one in Petticoat Lane.

It was about eleven o’clock in the morning; the housewives of Bethnal Green were out on the street hunting bargains in meat and vegetables for the Sunday dinner. One of the most interesting groups I passed was crowded about a pushcart where three sturdy old women, shouting at the top of their lungs, were reeling off bolt after bolt of cheap cotton cloth to a crowd of women gathered about their cart.

At another point a man was “knocking down” at auction cheap cuts of frozen beef from Australia at prices ranging from 4 to 8 cents a pound. Another was selling fish, another crockery, and a third tinware, and so through the whole list of household staples.

The market on Bethnal Green Road extends across a street called Brick Lane and branches off again from that into other and narrower streets. In one of these there is a market exclusively for birds, and another for various sorts of fancy articles not of the first necessity. The interesting thing about all this traffic was that, although no one seemed to exercise any sort of control over it, somehow the different classes of trade had managed to organize themselves so that all the wares of one particular sort were displayed in one place and all the wares of another sort in another, everything in regular and systematic order. The streets were so busy and crowded that I wondered if there were any people left in that part of the town to attend the churches.

One of the marvels of London is the number of handsome and stately churches. One meets these beautiful edifices everywhere, not merely in the West End, where there is wealth sufficient to build and support them, but in the crowded streets of the business part of the city, where there are no longer any people to attend them. Even in the grimiest precincts of the East End, where all is dirt and squalor, one is likely to come unexpectedly upon one of these beautiful old churches, with its quiet churchyard and little space of green, recalling the time when the region, which is now crowded with endless rows of squalid city dwellings, was, perhaps, dotted with pleasant country villages. These churches are beautiful, but as far as I could see they were, for the most part, silent and empty. The masses of the people enjoy the green spaces outside, but do not as a rule, I fear, attend the services on the inside. They are too busy.

It is not because the churches are not making an effort to reach the people that the masses do not go to them. One has only to read the notices posted outside of any of the church buildings in regard to night schools, lectures, men’s clubs and women’s clubs, and many other organizations of various sorts, to know that there is much earnestness and effort on the part of the churches to reach down and help the people. The trouble seems to be that the people are not at the same time reaching up to the church. It is one of the results of the distance between the classes that rule and the classes that work. It is too far from Whitechapel to St. James’s Park.’

Petticoat Lane by Charles Chusseau-Flaviens, 1911. Photograph courtesy George Eastman House

Booker T. Washington speaking in Atlanta in 1895

Click here to read ‘The Man Farthest Down, The Struggle of European Toilers’

You may also like to take a look at

Dennis Anthony’s Petticoat Lane

Laurie Allen of Petticoat Lane

The Wax Sellers of Wentworth St

The Streets Of Old London

JOIN ME FOR FOR A WALK THROUGH SPITALFIELDS THIS EASTER!

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR SPRING & SUMMER TOURS

Piccadilly, c. 1900

In my mind, I live in old London as much as I live in the contemporary London of here and now. Maybe I have spent too much time looking at photographs of old London – such as these glass slides once used for magic lantern shows by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society at the Bishopsgate Institute?

Old London exists to me through photography almost as vividly as if I had actual memory of a century ago. Consequently, when I walk through the streets of London today, I am especially aware of the locations that have changed little over this time. And, in my mind’s eye, these streets of old London are peopled by the inhabitants of the photographs.

Yet I am not haunted by the past, rather it is as if we Londoners in the insubstantial present are the fleeting spirits while – thanks to photography – those people of a century ago occupy these streets of old London eternally. The pictures have frozen their world forever and, walking in these same streets today, my experience can sometimes be akin to that of a visitor exploring the backlot of a film studio long after the actors have gone.

I recall my terror at the incomprehensible nature of London when I first visited the great metropolis from my small city in the provinces. But now I have lived here long enough to have lost that diabolic London I first encountered in which many of the great buildings were black, still coated with soot from the days of coal fires.

Reaching beyond my limited period of residence in the capital, these photographs of the streets of old London reveal a deeper perspective in time, setting my own experience in proportion and allowing me to feel part of the continuum of the ever-changing city.

Ludgate Hill, c. 1920

Holborn Viaduct, c. 1910

Trinity Almshouses, Mile End Rd, c. 1920

Throgmorton St, c. 1920

Highgate Forge, Highgate High St, 1900

Bangor St, Kensington, c. 1900

Ludgate Hill, c. 1910

Walls Ice Cream Vendor, c. 1920

Ludgate Hill, c. 1910

Strand Yard, Highgate, 1900

Eyre St Hill, Little Italy, c. 1890

Eyre St Hill, Little Italy, c. 1890

Muffin man, c. 1910

Seven Dials, c. 19o0

Fetter Lane, c. 1910

Piccadilly Circus, c. 1900

St Clement Danes, c. 1910

Hoardings in Knightsbridge, c. 1935

Wych St, c.1890

Dustcart, c. 1910

At the foot of the Monument, c. 1900

Pageantmaster Court, Ludgate Hill, c. 1930

Pageantmaster Court, Ludgate Hill, c. 1930

Holborn Circus, 1910

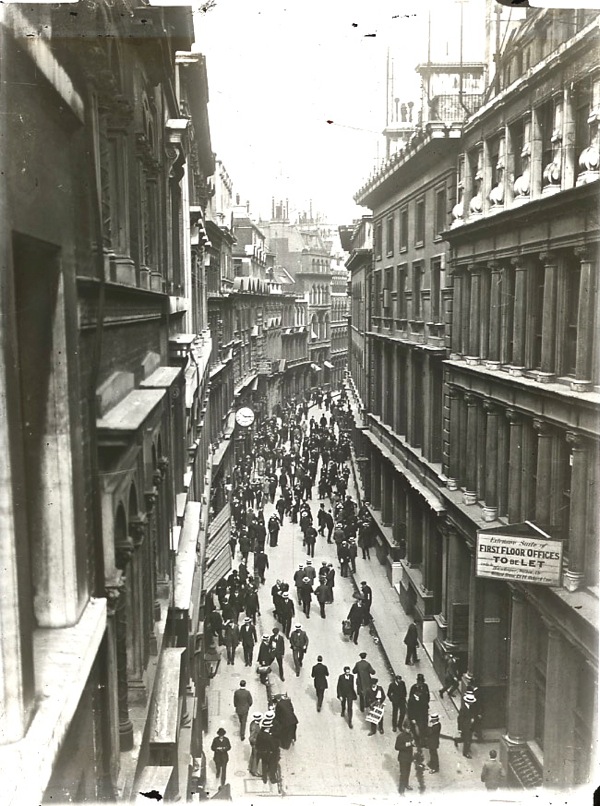

Cheapside, 1890

Cheapside ,1892

Cheapside with St Mary Le Bow, 1910

Regent St, 1900

Glass slides copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at