The Markets Of Old London

Tickets are available for my walking tour this Saturday!

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Clare Market c.1900

I never knew there was a picture of the legendary and long-vanished Clare Market – where Joseph Grimaldi was born – until I came upon this old glass slide among many thousands in the collection of the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society, housed at the Bishopsgate Institute. Scrutinising this picture, the market does not feel remote at all, as if I could take a stroll over there to Holborn in person as easily as I can browse the details of the photograph. Yet the Clare Market slum, as it became known, was swept away in 1905 to create the grand civic gestures of Kingsway and Aldwych.

Searching through this curious collection of glass slides, left-overs from the days of educational magic lantern shows – comprising many multiple shots of famous landmarks and grim old church interiors – I was able to piece together this set of evocative photographs portraying the markets of old London. Of those included here only Smithfield, London’s oldest wholesale market, continues trading from the same building, though Leather Lane, Hoxton Market and East St Market still operate as street markets, but Clare Market, Whitechapel Hay Market and the Caledonian Rd Market have gone forever. Meanwhile, Billingsgate, Covent Garden and Spitalfields Fruit & Vegetable Market have moved to new premises, and Leadenhall retains just one butcher selling fowl, once the stock-in-trade of all the shops in this former cathedral of poultry.

Markets fascinate me as theatres of commercial and cultural endeavour in which a myriad strands of human activity meet. If you are seeking life, there is no better place to look than in a market. Wherever I travelled, I always visited the markets, the black-markets of Moscow in 1991, the junk markets of Beijing in 1999, the Chelsea Market in Manhattan, the central market in Havana, the street markets of Rio, the farmers’ markets of Transylvania and the flea market in Tblisi – where, memorably, I bought a sixteenth century silver Dutch sixpence and then absent-mindedly gave it away to a beggar by mistake ten minutes later. I often wonder if he cast the rare coin away in disgust or not.

Similarly in London, I cannot resist markets as places where society becomes public performance, each one with its own social code, language, and collective personality – depending upon the nature of the merchandise, the location, the time of day and the amount of money changing hands. Living in Spitalfields, the presence of the markets defines the quickening atmosphere through the week, from the Thursday antiques market to the Brick Lane traders, fly-pitchers and flower market in Bethnal Green every Sunday. I am always seduced by the sense of infinite possibility when I enter a market, which makes it a great delight to live surrounded by markets.

These old glass slides, many of a hundred years ago, capture the mass spectacle of purposeful activity that markets offer and the sense of self-respect of those – especially porters – for whom the market was their life, winning status within an elaborate hierarchy that had evolved over centuries. Nowadays, the term “marketplace” is sometimes reduced to mean mere economic transaction, but these photographs reveal that in London it has always meant so much more.

Billingsgate Market, c.1910

Billingsgate Market, c.1910

Whitechapel Hay Market c.1920 (looking towards Aldgate)

Whitechapel Hay Market, c.1920 (looking east towards Whitechapel)

Porters at Smithfield Market, c.1910

Caledonian Rd Market, c.1910

Book sale at Caledonian Rd Market, c.1910

Caledonian Rd Market, c.1910

Caledonian Rd Market, c.1910

Covent Garden Market, c.1920

Covent Garden Market, c.1910

Covent Garden, c.1910

Covent Garden Market, 1925

Covent Garden Market, Floral Hall, c.1910

Leadenhall Market, Christmas 1935

Leadenhall Market, c.1910

East St Market, c.1910

Leather Lane Market, 1936

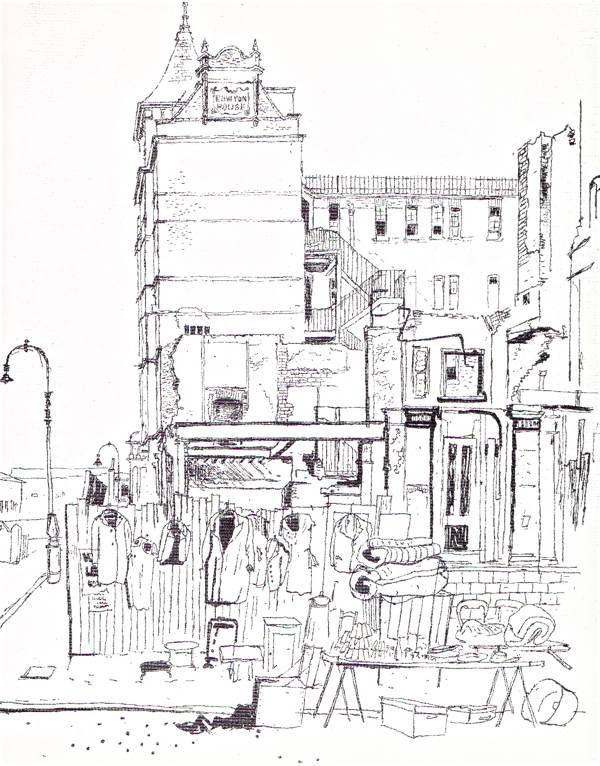

Hoxton Market, Shoreditch, 1910

Hoxton Market, Shoreditch, 1910

Spitalfields Market, c.1930

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to look at these old photographs of the Spitalfields Market by Mark Jackson & Huw Davies

Night at the Spitalfields Market

Other stories of Old London

A Walk With Suresh Singh

Tickets are available for my walking tour this Saturday!

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

I am very proud to be the publisher of A MODEST LIVING, Memoirs of a Cockney Sikh, London’s first Sikh biography, telling the story of one family in Spitalfields over seventy years. Suresh and I enjoyed a ramble round Spitalfields one day and he showed me some of the places that hold most meaning for him.

“I love Whitechapel Library, Aldgate East. It was the library I used to go to every Friday when I was at primary school. You could sit and read. It was just lovely. Upstairs was the art and music library. They had big oversize books of Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, the Impressionists, Matisse, Degas and Le Corbusier’s book about Chandigarh.

It was amazing to have this in Brick Lane, at the end of my street. You were given freedom to look at the books and could borrow twelve books and five records at a time. The librarian in the music library would order whatever you requested. Even if you asked for ‘Yes’ album, he would get it by next week. My dad had a record player and I learnt to be really careful with a record because when you returned it they would meticulously check it.

The library was a whole world. It taught me to read quietly. It exposed me to books that I might never have found. My mum and dad could not read or write. We had no books at home. I liked the art section because the books had pictures and I learnt that pictures told stories as well as words. The librarians always helped me and I could spend hours there. It was a sanctuary from the mayhem outside, a kind of university of the ghetto.”

“Christ Church School, Brick Lane, was my primary school. I loved it when I came back after a long visit to India at six years old. I have frightening memories of it too, as the place I had to go to after the freedom I had experienced in our village. My mum used to walk me here every day and I would walk home for dinner at Princelet St and come back again. School dinners were so bland but my mum gave me dal and roti.

The water fountain used to work and we could drink from it. I remember it as so high, my friends had to give me a lift up so I could drink from it. You pressed the button and it worked. There were little fish that lived in there.

Later on, Eric Elstob – a friend whom I worked for in the renovation of his house in Fournier St – was treasurer of the school and he restored the railings, which was lovely. A couple of years ago, they were repainting them blue and I asked them to paint a bit of my bike with the same colour to remind me of the great memories I have of this school. We used to have great jumble sales at Christmas. You could climb through the school and out through the back, past the gardens of the houses in Fournier St and Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church into Itchy Park, and out into Commercial St and Spitalfields Market. I loved it because it was a backstreet school.”

“I have fond memories of the rectory at 2 Fournier St when Eddie Stride was Rector. It is one of the few Hawksmoor houses. I helped Eddie wash the steps with Vim when the tramps pissed all over them. There used to be queues outside and Irene Stride made sandwiches for them.

It was a place where Eddie made me feel very welcome. I rang the bell or knocked on the door, and he would always open it to me. The door was never closed. I could always go in and play in the garden. Later on, there were big power meetings at the rectory when Eddie became the chairman of the Festival of Light. So you would meet people like Malcolm Muggeridge, Mary Whitehouse, Cliff Richard and Lord Longford coming and going. It was always an open house.

I was brought up as a Sikh but there were no gurdwaras in Spitalfields, and my dad said ‘You need some moral purpose,’ so he send us to Sunday school and that was how I became friends with Eddie Stride. He was a great friend to our family. He helped me get grants for further education from the Sir John Cass Foundation which led me to study architecture. I loved that time and these steps mean a lot to me. It is amazing how Vim can clean Portland stone. ”

“I always knew the Hanbury Hall as 22a Hanbury St. In those days, Christ Church was closed because it was unsafe and this was used for services instead. There was a youth club at the top of the building on Thursdays and Fridays and we had our Sunday school in the hall.

Because it was built as a Huguenot chapel, everyone used to say that this hall is older than the church and sometimes that used to scare me late at night. There were these big wooden doors that closed with a hasp and I always feared someone might come down the winding stone staircase. Later, when I was doing carpentry work, Eddie gave me the task of housing the remains of the smallpox victims that they found when they were cleaning out the crypt.

When I started a group, we were allowed to rehearse in the vestry at the back. This place was a playground for me but also a church where services were held until the eighties. Then I helped move the furniture from here back to Christ Church. I remember we put the communion table on casters and I had to clear out all the copies of Lord Longford’s pornography report which were being stored in the church.

This hall was a treasure because it had a lovely atmosphere but also a haunted atmosphere too. It was the main meeting point for all of us in Spitalfields at that time.”

“Once, the Truman Brewery in Brick Lane was a dark scary corridor for me. It was my route from my home in Princelet St to my secondary school, Daneford in Bethnal Green. At that time, it used to smell of hops and it was dark and dirty. I got beaten up by a bunch of fascist skinheads at the corner of the brewery where it meets Buxton St. I still try to avoid this route but like a magnet it draws me through. I used to run through or cycle because to go round the other way was much longer and sometimes more scary- you would have to cut past Shoreditch Station and round the back to Cheshire St.

So this was the quickest route but it was like going through a factory. The brewery was always there in my childhood. The smell and the noise were twenty-four hours, and it was always dark beneath the brewery walls. The brewery was a landmark and I remember smoke coming out of that chimney. It was a place that you had no choice but to pass through. At the other end of the brewery was where the skinheads hung out but at this end was the Bengali area where I felt safer. Every day I hoped I would not get my head kicked in as I went to school.

As a kid, I found these long brewery walls interminable. I walked and walked and thought, ‘Will I ever get through to the end?’ It still scares me in a way.”

“I used to pass Franta Belsky’s sculpture in Bethnal Green every day when I walked along the little passageway to Daneford Secondary School. Today, I am wearing the tank top my mum knitted when I was eleven and I remember wearing it to a non-school uniform day all those years ago.

I always used to see this sculpture out of the side of my eye. My friends would say, ‘You go on Singhey, I dare you to touch her breasts and come back down again.’ But slowly I began to appreciate the beauty of it and began looking at books of Henry Moore and David Smith. It was a lovely thing to see before you went to school every day. It comforted me to see a woman and her baby because I thought, ‘That’s how my mum cares for me.’ It gave me a sense of security. I thought, ‘How amazing that we have a piece of sculpture outside our school.’ It made me feel proud because of the sculpture. My dad used to take me to Hyde Park where there were Henry Moores next to the Serpentine. I thought, ‘We’re on a par with the West End here in Bethnal Green.’

I slowly started loving it. I loved her plait and it reminded me of when I had a topknot. I appreciated it in different types of light and I still love it today.”

Suresh Singh & Jagir Kaur at 38 Princelet St (Photograph by Patricia Niven)

You may also like to read about

So Long, Chris Georgiou

Tickets are available for my walking tour this Saturday

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Tailor Chris Georgiou (1945-2024) died on 28th May aged seventy-nine. A funeral will be held at the Greek Orthodox Church of St Sophia, Moscow Rd, W2 4LQ this Friday 21st June at 2pm.

“I’ve worked seven days a week for forty-five years – each morning I come in about half eight and stay until seven o’clock,” tailor Chris Georgiou assured me, “If I didn’t like it, I wouldn’t do it.”

I was standing in his tiny tailoring shop situated in one of the last quiet stretches of the Kings Cross Rd. “You don’t want to retire,” Chris advised me, thinking out loud and wielding his enormous shears enthusiastically, “The bank manager round the corner retired and he’s had three heart attacks in three years and he now he takes thirty-five pills a day. He came to see me. ‘Chris, never retire!’ he said. A friend of mine, a tailor who worked from home, he retired but after a couple of years he came to see me, ‘Chris,’ he said, ‘Can I come and help you for a couple of days each week? I don’t want any money, I just need a reason to walk down the road.'”

Chris shook his head at the foolishness of the world as he resumed cutting the cloth and thus I was assured of the unlikelihood of Chris ever retiring. And why should when he had so many devoted long-term customers who appreciate his work? As I discovered, when a distinguished-looking gentleman came in clutching an armful of striped shirts that matched the one he was wearing and readily admitted he was a customer of fourteen years standing. Thus it was only a brief interview that Chris was able to grant me but, like all his work, it was perfectly tailored.

“I started out to be tailor at twelve years old, to learn this job you have to start early and you need a lot of patience to hold a needle. My mother was a very good dressmaker and she made shirts, that’s where I got it from. In Cyprus, when you finish school at twelve years old, you must choose a trade. I always liked to dress smart, so I said, ‘I’m going to be a tailor.’ I came from a poor family and I couldn’t have gone to college.

So learnt from a tailor in our village of Zodia. First, I learnt to make trousers and then I learnt to make a jacket, and then it was time to change. After that, I went to another place and said, ‘I know how to make jackets.’ I told lies and I got the job, and I started to learn the art of tailoring. Then I came here in 1968, under contract to a maker of leather wear in Farringdon Rd but, after a year, I told my boss I was going off to do tailoring. And I went to several tailors to see how they do it in England and I bought this shop from one of them in 1969, just a year after I arrived. At first, I used to get jobs from other tailors doing alterations and then I acquired my own customers. 95% of them are barristers and I have never advertised, all my customers have come through recommendations.

When I make a suit, it’s not for the customer, it’s for the people who see the suit. That’s my secret. They wear their suits in chambers and the others ask them where they get their suits. My customers come from the City. It pleases me when you do something good, satisfy your customer and they leave happy. You can’t get rich by tailoring but you can make a good living. I’ve made a lot of suits for famous people whom I’m not at liberty to mention but I can tell you I made a dinner suit for Roger Daltrey, when he got an award for charity work from George Bush, and I made a suit for Lord Mayhew. He brought two security guards who stood outside the shop. I made suits for both his sons and he asked them where they got their suits. He used to go to Savile Row but now he comes here.

I don’t go out for lunch, I eat food prepared by my wife that I bring with each day from East Finchley. She doesn’t see too much of me, that must be why my marriage has lasted forty years.”

“When I make a suit, it’s not for the customer, it’s for the people who see the suit”

“To learn this job you have to start early and you need a lot of patience to hold a needle”

“It pleases me when you do something good, satisfy your customer and they leave happy”

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

You may also like to read about

The Alteration Tailors Of The East End

James Boswell’s East End

A few years ago, I visited a leafy North London suburb to meet Ruth Boswell – an elegant woman with an appealing sense of levity – and we sat in her beautiful garden surrounded by raspberries and lilies, while she told me about her visits to the East End with her late husband James Boswell who died in 1971. She pulled pictures off the wall and books off the shelf to show me his drawings, and then we went round to visit his daughter Sal who lives in the next street and she pulled more works out of her wardrobe for me to see. And when I left with two books of drawings by James Boswell under my arm as a gift, I realised it had been an unforgettable introduction to an artist who deserves to be better remembered.

From the vast range of work that James Boswell undertook, I have selected these lively drawings of the East End done over a thirty year period between the nineteen thirties and the fifties.There is a relaxed intimate quality to these – delighting in the human detail – which invites your empathy with the inhabitants of the street, who seem so completely at home it is as if the people and cityscape are merged into one. Yet, “He didn’t draw them on the spot,” Ruth revealed as I pored over the line drawings trying to identify the locations, “he worked on them when he got back to his studio. He had a photographic memory, although he always carried a little black notebook and he’d just make few scribbles in there for reference.”

“He was in the Communist Party, that’s what took him to the East End originally,” she continued, “And he liked the liveliness, the life and the look of the streets, and and it inspired him.” In fact, James Boswell joined the Communist Party in 1932 after graduating from the Royal College of Art and his lifelong involvement with socialism informed his art, from drawing anti-German cartoons in style of George Grosz during the nineteen thirties to designing the posters for the successful Labour Party campaign of 1964.

During World War II, James Boswell served as a radiographer yet he continued to make innumerable humane and compassionate drawings throughout postings to Scotland and Iraq – and his work was acquired by the War Artists’ Committee even though his Communism prevented him from becoming an official war artist. After the war, as an ex-Communist, Boswell became art editor of Lilliput influencing younger artists such as Ronald Searle and Paul Hogarth – and he was described by critic William Feaver in 1978 as “one of the finest English graphic artists of this century.”

Ruth met James in the nineteen-sixties and he introduced her to the East End. “We spent quite a bit of time going to Blooms in Whitechapel in the sixties. We went regularly to visit the Whitechapel when Robert Rauschenberg and the new Americans were being shown, and then we went for a walk afterwards,” she recalled fondly, “James had been going for years, and I was trying to make my way as a journalist and was looking at the housing, so we just wandered around together. It was a treat to go the East End for a day.”

Rowton House

Old Montague St, Whitechapel

Gravel Lane, Wapping

Brushfield St, Spitalfields

Wentworth St, Spitalfields

Brick Lane

Fashion St, illustration by James Boswell from “A Kid for Two Farthings” by Wolf Mankowitz, 1953.

Russian Vapour Baths in Brick Lane from “A Kid for Two Farthings.”

James Boswell (1905-1971)

Leather Lane Market, 1937

Images copyright © Estate of James Boswell

You might also like to take a look at

In the footsteps of Geoffrey Fletcher

In Old Holborn

Next tickets for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS are available for Saturday 22nd June

Holborn Bars

Even before I knew Holborn, I knew Old Holborn from the drawing of half-timbered houses upon the tobacco tins in which my father used to store his rusty nails. These days, I walk through Holborn once a week on my way between Spitalfields and the West End, and I always cast my eyes up in wonder at this familiar fragment of old London.

Yet, apart from Leather Lane and the International Magic Shop on Clerkenwell Rd, I rarely have reason to pause in Holborn. It is a mysterious, implacable district of offices, administrative headquarters and professional institutions that you might never visit, unless you have business with a lawyer, or seek a magic trick or a diamond ring. So this week I resolved to wander in Holborn with my camera and present you with some of the under-appreciated sights to be discovered there.

Crossing the bed of the Fleet River at Holborn Viaduct, I took a detour into Shoe Lane. A curious ravine of a street traversed by a bridge and overshadowed between tall edifices, where the cycle-taxis have their garage in the cavernous vaults receding deep into the brick wall. John Stow attributed the name of Holborn to the ‘Old Bourne’ or stream that ran through this narrow valley into the Fleet here and, even today, it is not hard to envisage Shoe Lane with a river flowing through.

Up above sits Christopher Wren’s St Andrew’s, Holborn, that was founded upon the bank of the Fleet and stood opposite the entrance to the Bishop of Ely’s London residence, latterly refashioned as Christopher Hatton’s mansion. A stone mitre upon the front of the Mitre Tavern in Hatton Garden, dated 1546, is the most visible reminder of the former medieval palace that existed here, of which the thirteenth century Church of St Etheldreda’s in Ely Place was formerly the chapel. It presents a modest frontage to the street, but you enter through a stone passage way and climb a staircase to discover an unexpectedly large church where richly-coloured stained glass glows in the liturgical gloom.

Outside in Ely Place, inebriate lawyers in well-cut suits knock upon a wooden door in a blank wall at the end of the street and brayed in delight to be admitted by this secret entrance to Bleeding Heart Yard, where they might discreetly pass the afternoon in further indulgence. Barely a hundred yards away across Hatton Garden where wistful loners eyed engagement rings, Leather Lane Market was winding down. The line at Boom Burger was petering out and the shoe seller was resting his feet, while the cheap dresses and imported fancy goods were packed away for another day.

Just across the road, both Staple Inn and Gray’s Inn offer a respite from the clamour of Holborn, with magnificent tranquil squares and well-kept gardens, where they were already raking autumn leaves from immaculate lawns yesterday. But the casual visitor may not relax within these precincts and, when the Gray’s Inn Garden shuts at two-thirty precisely, you are reminded that your presence is that of an interloper, at the gracious discretion of the residents of these grand old buildings.

Beyond lies Red Lion Sq, laid out in 1684 by the notorious Nicholas Barbon who, at the same time, was putting up cheap speculative housing in Spitalfields and outpaced the rapacious developers of our own day by commencing construction in disregard of any restriction. Quiet benches and a tea stall in this leafy yet amiably scruffy square offer an ideal place to contemplate the afternoon’s stroll.

Then you join the crowds milling outside Holborn tube station, which is situated at the centre of a such a chaotic series of junctions, it prompted Virginia Woolf to suggest that only the condition of marriage has more turnings than are to be found in Holborn.

The One Tun in Saffron Hill. reputed to be the origin of the Three Tuns in ‘Oliver Twist’

In Shoe Lane

St Andrew Holborn seen from Shoe Lane

On Holborn Viaduct

Christopher Wren’s St Andrew Holborn

In St Etheldreda’s, Ely Place

Staircase at St Etheldreda’s

The Mitre, Hatton Garden

Charity School of 1696 In Hatton Garden by Christopher Wren

Choosing a ring in Hatton Garden

In Leather Lane

Seeking sustenance in Leather Lane

Shoe Seller, Leather Lane

Barber in Lamb’s Conduit Passage

Staple Inn, 1900

In Staple Inn

In Staple Inn

In Gray’s Inn

In Gray’s Inn Gardens

In Gray’s Inn

Chaos at Holborn Station

Rush hour at Holborn Station

Fusiliers memorial in High Holborn

You may also like to take a look at

Moyra Peralta At Crispin St Night Shelter

Next tickets for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS are available for Saturday 22nd June

Remembering photographer Moyra Peralta (1936-2024) who died on 8th May aged eighty-eight

“I am standing in the one-time women’s dormitory and have brought a photograph of my friend Peggy. Her husband had died and she could not bear to remain alone in her home surrounded by thoughts of him. Chance, desperation and loss brought many people to Providence Row, myself included, and its existence was a lifeline – a refuge from the ruthlessness of life.”

Providence Row, the night shelter for destitute men, women and children in Crispin St, opened in 1860 and operated until 2002 when it moved to new premises in Wentworth St, where it continues now as a day centre. Twenty years on, photographer Moyra Peralta, who worked at Providence Row in the seventies and eighties, returned to have a final look at the familiar rooms that had seen so much life and she took these evocative pictures published here for the first time.

Reconstructed and expanded to create an uneasy architectural hybrid, the building is now student housing for the London School of Economics, where once it housed Students of the London School of the Economics of Pennilessness. Famously, this was where James Mason came to interview those dignified gentlemen down on their luck in ‘The London Nobody Knows.’

Over one one hundred and forty years, Providence Row offered refuge to the poorest and most vulnerable of Londoners and, at the last moment before the building was gutted, Moyra went in search of the residue of their hope and despair, their yearning and their loneliness. She found a sacred space resonant with echoes of the past and graven with the tell-tale marks of those who had passed through.

Peggy

Memorial plaque to the opening of Providence Row in 1860

The yard where Roman skeletal remains were excavated

Looking towards the City of London

HE WHO OPENS THIS DOOR SHALL BE CURSED FOR A HUNDRED AND ONE YEARS

Former women’s dormitory

Women’s dormitory in the sixties

This free-standing disconnected facade is still to be seen in Artillery Lane

Gerry B

“I am struck by the notion that with a careless step or two, I too might meet a premature end as I circumnavigate holes in floors and gaping apertures in walls.”

The room where Moyra Peralta slept when she worked at Providence Row and where she wrote these words – “Only the present is real – for some reason I feel this most of all when listening to the lorries moving at the street’s end and the slamming of crates being unloaded in Crispin St. There is a rhythm to the deep sound of the slow low-thrumming engines that I like to contemplate. On sleep-over, rising early from my bed following the refuge nightshift, I watch what is now – 6:00am. A thousand cameos change and regroup under my gaze. Jammed traffic forms and reforms where the roads meet.”

Photographs copyright © Estate of Moyra Peralta

You may also like to read these other stories about the Crispin St Night Shelter

The Doss Houses of Spitalfields

and see Moyra Peralta’s other work

Moyra Peralta’s Portraits

Next tickets for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS are available for Saturday 22nd June

Remembering photographer Moyra Peralta (1936-2024) who died on 8th May aged eighty-eight

Sylvia in Tenterground, Spitalfields

This compelling photograph has been haunting me with its tender emotional resonance. Sylvia’s once-smart shoes and flowery dress tell us about the life she wished to lead – and maybe about the life she had led – yet it is apparent from Moyra Peralta’s affectionate portrait that the life Sylvia aspired to was lost to her forever. Unwillingly to enter a night shelter, she slept rough in Spitalfields in the seventies and today this photograph exists as the only lasting evidence that, in spite of her straitened circumstance, Sylvia kept her self-respect.

Through the seventies and until the end of the nineties, Moyra Peralta befriended people living on the street in the capital, visiting them several times each week. “I miss that world terribly,” she admitted to me, looking back on it, “my relationships were more social than photographic, but in the process of those relationships I took portraits – there are those here that I knew over thirty years, most of these people I knew for well over twenty to thirty years.”

“Definitions of the homeless lost all meaning for me.” Moyra emphasised, “As a photographer, I tried to show the human face, rather than the problem of homelessness itself because those termed ‘homeless’ are not an alien grouping – they are people of all ages and backgrounds, many of whom have met with crippling misfortunes.”

Moyra’s intimate photographs succeed as portraits of heroic individuals, evoking the human dignity of those marginalised by society. “To me, those I have photographed are an important part of our social history.” Moyra asserted to me, “I want my photographs to rescue people from oblivion and celebrate their lives lived in a climate of disregard.”

John T in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Bert known as ‘Birdman’ slept outdoors since the age of fourteen. He had an affinity with the black swans and sparrows in St James’ Park and was treated with tolerance by the Park Police.

Two men sitting in a cellar.

Maxie on the steps of the Cumberland Hotel, Marble Arch.

Maxie pours Stan a drink at Marble Arch.

Eddie and Brian tell tall stories on Kinsgway

Brian raps on the church door, Kingsway

Man and a cat in a Cyrenian short stay hostel, 1974.

Grant and pal laughing at the Bullring, South Bank

Mary reads the Big Issue in Holborn

Tommy M in Lincoln’s Inn Fields

Bill H, Cyrenian House, Barons Court, in the seventies.

Brian D at Middlesex Hospital, 1997

Brian’s begging hand.

Francis at Cable St

JW and Jim at Pratt St, Camden

John T, Storyteller, Whetstone 1995.

John T, the valentine.

Kerry’s Christmas Tree, Kingsway 1994.

Drag artistes from the Vauxhall Tavern give a surprise performance to entertain guests at a night shelter, 1974

Drag artistes improvise costumes at the Vauxhall shelter.

Billy and Maxie, two ex-servicemen at Marble Arch, 1976. Billy (left) died of a broken heart the year after Maxie’s death

Billy at Marble Arch in the seventies.

Sid takes tea at Ashmore Rd short stay hostel in West London.

Resident washing dishes at West London Mission, St Luke’s House – part of former Old Lambeth Workhouse, 1974.

Tiny, ex-circus hand and born wanderer extends a greeting at the Vauxhall Night Shelter, 1974.

Man and his bottle in Central London, seventies

Disabled Showman Zy with his wheels.

Zy plays a trick with his teeth

Brian the Poet in Kingsway, 1994.

Photographs copyright © Estate of Moyra Peralta

You may also like to read about