Rodney Archer, Aesthete

Rodney Archer kindly took me to lunch at E.Pellicci yesterday, but first I went round to his eighteenth century house in Fournier St to take this portrait of him in front of his cherished fireplace that once belonged to Oscar Wilde. One day in 1970, Rodney was visiting an old friend who lived in Tite St next to Wilde’s house and saw the builders were doing renovations, so he seized the opportunity to walk through the door of the house that had once been the great writer’s dwelling. The fireplace had been torn out of the wall in Wilde’s living room as part of a modernisation of the property and the workmen were about to carry it away, so Rodney offered to buy it on the spot. For ten pounds he acquired a literary relic of the highest order, the fine pilastered fireplace with tall overmantle that you see above, and which today has become a shrine to Wilde that is the centrepiece of Rodney’s first floor living room in Fournier St. You can see Spy’s famous caricature of Wilde up on the chimneypiece, but the gem of Rodney’s Wilde collection is a copy of Lord Alfred Douglas’ poems with pencil annotations by Douglas himself. Encountering these artifacts in this environment – that already possess such a potent poetry of their own, amplified by their proximity to each other – is especially enchanting.

Rodney has allowed the patina of ages to remain in his house, enhanced by his sensational collection of pictures, carpets, furniture, books, china and god-knows-what, accumulated over all the years he has lived in it, which transform the house into three-dimensional map of his vigorous mind, crammed with images, stories and all manner of cultural enthusiasms. In Rodney’s house, anyone would feel at home the minute they walked in the door because the result of all these accretions is that everything has arrived in its natural place, yet nothing feels arranged. It is a relaxing place, with reflected light everywhere, and although there is so much to look at and so many stories to learn, it is peaceful and benign, like Rodney himself. Rodney’s style can never be replicated by anyone else, unless you became Rodney and you could live through those years again.

Rodney made his home in London’s most magical street in 1980. It came about after his mother fell down a well at The Roundhouse and broke her hip while visiting a performance of “The Homosexual (or The Difficulty of Sexpressing Yourself)” by Copi in which Rodney was starring. It was the culmination of Rodney’s distinguished career of just eight years as an actor, that included playing the Player Queen in Hamlet at the Bristol Old Vic in a production with Richard Pasco in the title role and featuring Patrick Stewart as Horatio.

After she broke her hip, Rodney’s mother told him that her doctor insisted she live with her son, much to Rodney’s surprise. Gamely, Rodney agreed, on the condition they find somewhere large enough to live their own lives with some degree of independence, and rang up his friends Riccardo and Eric who lived in Fournier St, asking them to keep their eyes open for any house that went on sale. Within three months, a house came up. It was the only one they looked at and Rodney has lived there happily ever since. Thirty years ago, Spitalfields was not the desirable location it is today, “My mother thought I was joking when I told her where I wanted live,” declared Rodney, raising his eyebrows, “Now it would nice if there were more people living here who were not millionaires. I visit people in houses today where there are ghosts of people I used to know and the new people don’t know who they were, it’s sad.”

Rodney’s roots are in East London, he was born in Gidea Park, but once his father (a flying officer in the RAF) was killed in action over Malta in 1943, his mother took Rodney and his sister away to Toronto when they were tiny children and brought them up there on her own. Rodney came back to London in 1962 with the rich Canadian accent (which sounds almost Scottish to me) that he retains to this day, in spite of the actor’s voice training he received at Lamba which has imparted such a mellifluous tone to his speech. After his brief years treading the boards, Rodney became a teacher of drama at the City Lit and ran the Operating Theatre Company, staging his own play “The Harlot’s Curse” (co-authored with Powell Jones) in the Princelet St Synagogue with great success.

“When I retired, I decided to do whatever I wanted to do,” announced Rodney with a twinkly smile, at this point in his life story. “Now I am having a wonderful third act. Writing about that time, my mother, the cats and me…” he said, introducing the long-awaited trilogy of autobiographical fiction that he is currently working on, in which the first volume will cover his first eight years in Spitalfields concluding with the death of his mother in 1988, the second volume will conclude with the death of his friend Dennis Severs in 1999 and the third with the death of Eric Elstob. (Elstob was a banker who loved architecture and left a fortune for the refurbishment of Christ Church, Spitalfields.) “There is something about the nature of Spitalfields, that fact becomes fiction – as you become involved with the lives of people here, it gets you telling stories.” explained Rodney, expressing a sentiment that is close to my own heart too.

Now it was time for lunch and, as we walked hungrily up Brick Lane towards Bethnal Green in the Spring sunshine, the postman saluted Rodney and, on cue, the owner of the eel and pie shop leaned out of the doorway to give him a cheery wave too, then, as if to mark the occasion as auspicious, we saw the first shiny new train run along the recently completed East London Line, gliding across the newly constructed bridge, glinting in the sunlight as it passed over our heads and sliding away across Allen Gardens towards Whitechapel. This is the elegant world of Rodney Archer, I thought.

Turning the corner into Bethnal Green Rd, I asked Rodney about the origin of his passion for Wilde and when he revealed he once played Algernon in “The Importance of Being Earnest” at school, his intense grey-blue eyes shone with excitement. It made perfect sense, because I felt as if I was meeting a senior version of Algernon who retained all the wit, charm and sagacity of his earlier years, now having “a wonderful third act” in an apocryphal lost manuscript by Oscar Wilde, recently discovered amongst all the glorious clutter in a beautiful old house in Fournier St, Spitalfields.

Pelliccis' celebrity album

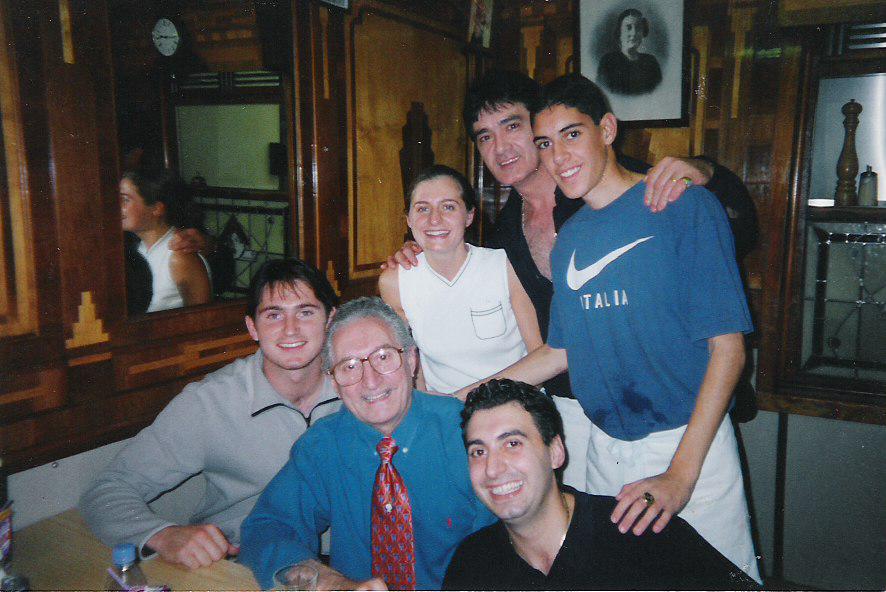

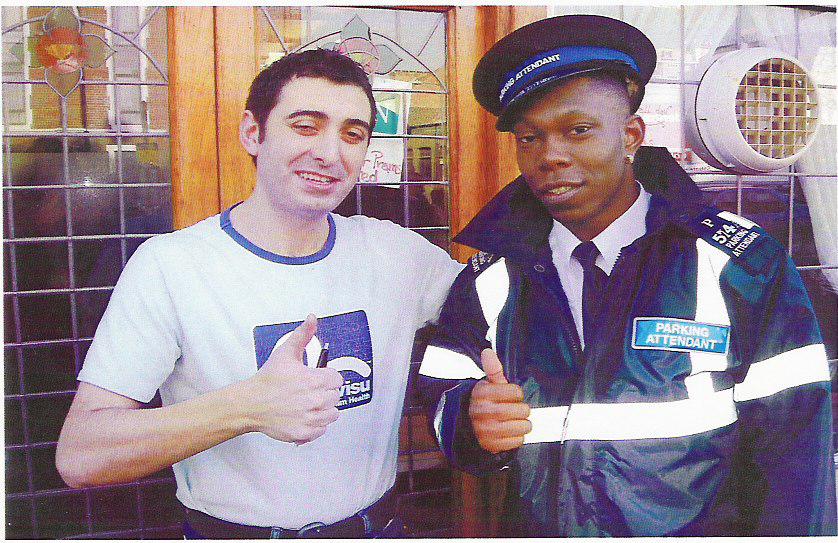

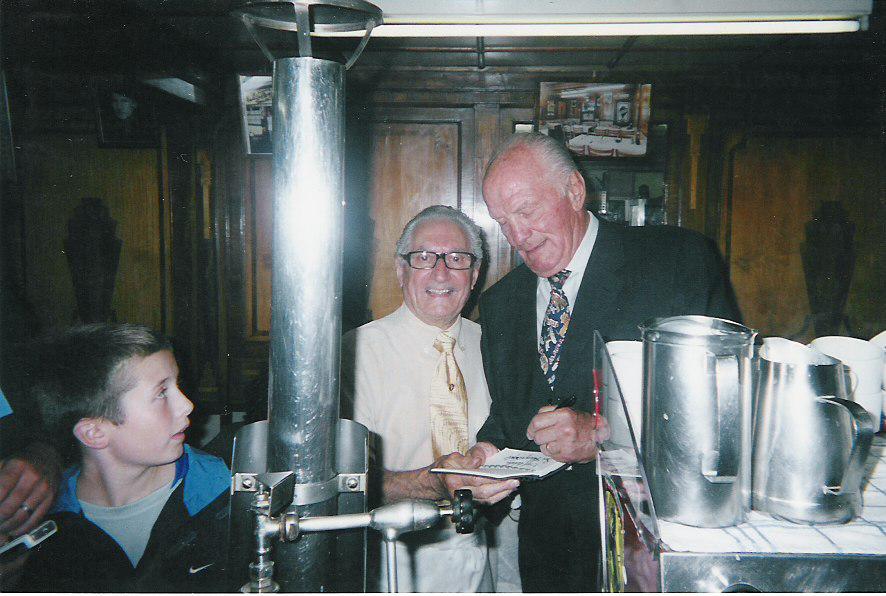

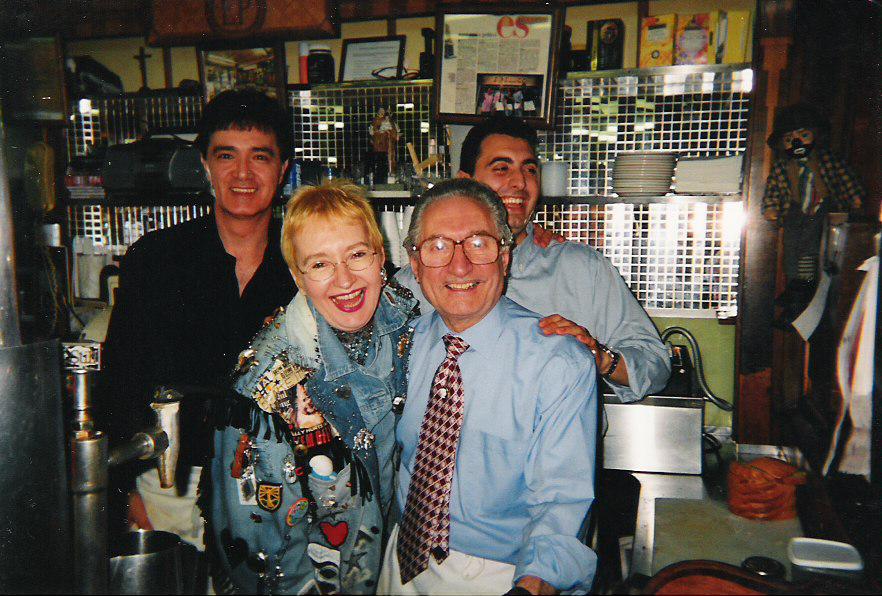

For over fifteen years they have kept a celebrity album behind the counter at E.Pellicci, the Italian family-run cafe in the Bethnal Green Rd that was founded in 1900 by Priamo Pellicci. Salvatore (on the extreme left of the picture above) started the album after Julie Christie came in for a cup of coffee years ago and they did not think to ask for her picture until she had gone. So Salvatore decided that any celebrity who passes through must be recorded for posterity, either in a snapshot or at very least by an autograph on a scrap of paper. Regular customers will be familiar with this fat little album which is brought out frequently, whenever anyone feels like leafing through the pages of treasured images and savouring the memorable moments enshrined there, but now thanks to generosity of the Pellicci family I am able to publish a choice selection here for you to enjoy.

The distinguished gentleman with the stylish glasses who recurs throughout these pictures is Nevio Pellicci senior and the skinny young man who grew up to develop Groucho Marx eyebrows is Nevio Pellicci junior (in the green shirt above) whose glamorous sister Anna Pellicci is also to be seen completing the happy family group in many of the photographs.

Colin Farrell and Anna Friel were photographed at Pelliccis just last July whilst filming “The London Boulevard” and there is no doubt that Colin carries the picture above with his graphic features and charismatic emotional presence, just as we are accustomed to seeing him do with such exuberant success in the cinema. But in this instance, while he makes a plausible show of looking cool at first glance, on closer inspection there is an undeniable element of the-rabbit-caught-in-the-headlights about his expression, whereas on the right hand side of the picture Nevio Pellici junior is hamming it up with gleeful reckless abandon.

In fact, as I examined these pictures in detail, it dawned on me that the real star turn here is not delivered by any of the celebrities, it is Nevio Pellicci junior himself with his outrageous cartoon features who reveals the most potent star quality on display. Scrolling through these images, I was almost blinded by his dazzling grin that has a wattage sufficient to light up the entire Bethnal Green Rd at night. Only hoary old troupers like Michael Gambon and Su Pollard manage to avoid being upstaged by young Nevio’s incandescent smile.

The truth is that I find the open-hearted playfulness of this album irresistible. Here you see the Pellicci family (except Maria Pellicci who is always in the kitchen) at home over the last fifteen years as they participate in the long-running drama enacted daily at their beloved cafe. And by the end of this series, Nevio Pellicci junior has taken over from his father Nevio Pellicci senior in Bethnal Green, just as Michael Douglas took over from Kirk Douglas in Hollywood. Interestingly, a comparison of the images of Nevio senior and Nevio junior reveals that Nevio junior inherited his trademark smile from Nevio junior, just as Michael inherited the dimple from Kirk.

If you want to see the full album for yourself and pore over all the autographs too, you simply have to go round to E.Pellicci at 332 Bethnal Green Rd, and if you are a celebrity you should be aware that you cannot truly claim with any credibility to have arrived until you have got your picture in the Pelliccis’ book. Salvatore confided that he was thinking of getting the famous album insured, which sounds like a wise move to me because it is priceless.

Eastenders star Patsy Palmer, who grew up round the corner in Columbia Rd, experiences an emotional return to the cafe where she once enjoyed spaghetti as a little girl.

David Schwimmer takes a break from filming “Run Fat Boy Run” in Columbia Rd to chill with his new friends at Pelliccis in 2007.

Eager young Frank Lampard in 1998 when he played for West Ham before he transferred to Chelsea.

Better known as Sergeant Lynch from “Z Cars,” James Ellis knows how to froth a coffee.

Dizzee Rascal takes a break from filming a video to hang with his brutha in the hood, Nevio.

Clive Owen enjoyed a slap-up breakfast with all the trimmings.

Boxing legend Sir Henry Cooper is proud to make his mark at Pelliccis.

Michael Gambon, who signed himself as Dumbledore, re-enacts a ham sandwich for the camera.

Coronation St’s Ali King and Nevio Pellicci deny all the rumours.

Lil Peters flirts shamelessly with two Chelsea Pensioners.

Ross Kemp and the Pellicci boys.

Jools Holland always pops in when he’s in the East End.

“I’m completely stuffed,” declared Su Pollard.

Hookey Alf of Whitechapel

In 1877, photographer John Thomson and radical journalist Adolphe Smith published “Street Life in London” in twelve monthly parts. A series of portraits of common people following upon the model of Henry Mayhew’s “London Labour and London Poor,” adding photography to the project.

“We have sought to portray these harder phases of life, bringing to bear the precision of photography in illustration of our subjects. The unquestionable accuracy of this testimony will enable us to present true types of the London poor and shield us from the accusation of either underrating or exaggerating individual peculiarities of appearance.” wrote the authors in their joint preface.

At first, I was attracted by the evocative photography yet suspicious of the dubious claim of scientific detachment, but when I read this plain account of the life of a man in Whitechapel my sympathies shifted. In fact, “Street Life in London” provided sympathetic interpretation of the lives of the poor for curious middle class readers who wanted to learn more about their fellow men and women.

In the photograph before us we have the calm, undisturbed face of the skilled artisan who has spent a life of tranquil, useful labour, and can enjoy his pipe in peace, while under him sits a woman whose painful expression seems to indicate a troubled existence, and a past which even drink cannot obliterate. By her side, a brawny, healthy “woman of the people” is not to be disturbed from her enjoyment of a “drop of beer” by domestic cares and early acclimatizes her infant to the fumes of tobacco and alcohol. But in the foreground the camera has chronicled the most touching episode. A little girl, not too young, however, to ignore the fatal consequences of drink, has penetrated boldly into the group, as if about to reclaim some relation in danger, and drag him away from evil companionship. There is no sight to be seen in the streets of London more pathetic than this oft-repeated story – the child leading home the drunken parent.

The most remarkable figure in this group is that of “Ted Coally” or “Hookey Alf,” as he is called according to the circumstances. His story is a simple illustration of the accidents that may bring a man into the streets, though born of respectable parents, well-trained and of steady disposition. This man’s father worked in a brewery, earned large wages, married, kept a comfortable home, and apprenticed his son to the trunk-making and packing trade. The boy frequently helped to affix heavy cases to a crane, so that they might be lowered from the top floor of a warehouse into the street. As the boxes were lined up it required considerable strength to push them out of the loop-hole out into the street, and, the young apprentice having inherited his father’s stalwart form, was selected for this work.

On one occasion, however, he threw the whole of his weight against a huge case which, through some mistake, had not been lined with tin; of course the case yielded at once to so tremendous a shock, it swung out into the street, and the lad carried away by his own unresisted impetus, fell head foremost to the pavement below. This accident at once put an end to his career in the trunk and packing trade, and rendered all the expense of his apprenticeship useless.

He recovered, it is true, from the fall, but has ever since been subject to epileptic fits. Finding that under these circumstances, he could no longer attempt complicated and difficult work, he thought he would seek out his living in one of those occupations where mere muscular strength is the chief qualification required. Thus he was able for some time to make his living as a coal porter but, even in this more humble calling, fate seemed to conspire against him. While high up on an iron ladder near the canal, at the Whitechapel coal wharfs, he twisted himself round to speak to someone below, lost his balance and fell head first to the ground. Hastily conveyed to the London Hospital, it was discovered that he had broken his right wrist and his left arm. The latter limb was so seriously injured that amputation was unavoidable, and when Ted Coally reappeared in Whitechapel society, a hook had replaced his lost arm. Thus crippled, he was no longer fit for regular work of any description, and having that time lost his father, the family soon found themselves reduced to want.

“Hookey Alf,” as he was now called, did not, however, lose heart, and, pocketing his pride, he wandered from street to street in search of any sort of work he could find. Hovering in the vicinity of the coal-yards he often met his old fellow-workers, and whenever a little extra help was required they gladly offered him a few pence for what feeble assistance he could render. Gradually he became accustomed to the use of his hook, and proved himself of more assistance than might have been anticipated, but, nevertheless, he has never been able to secure anything like regular employment.

He may often be found waiting around the brewery in the Whitechapel Rd, where ten or twelve tons of coal are frequently taken during the course of the day. “Hookey” stands here on guard, in the hope that when the coal arrives there will be some need of his services to unload. On these occasions he will earn a meal and few pence, and with this he returns home rejoicing. But, if after a long day’s patient endeavour he fails to make anything, the worry and disappointment will probably cause an attack of epilepsy, and thus add ill-health to poverty.

The tender concern of his mother cannot soothe the wounded feelings of the strong man. The energy and will are still there, it is the power of action alone that is wanting, and this good-natured honest man, feels he ought to be supporting his mother and sister, while in reality he is often living off their meagre earnings. The position is certainly trying, and it is difficult to make poor “Hookey” understand that an epileptic cripple cannot be expected to fulfil the same duties as a man in sound health.

Perhaps the lowest depths of misery were reached when “Hookey” in despair, slung a little string around his neck to hold in front of him a box or tray containing Vesuvians, and presented himself at the entrance of a neighbouring railway station, and sought to sell a few matches. “Hookey’s” misfortunes will, however, serve for one good purpose. They demonstrate that even those who resort to the humblest methods of making money in the streets are not always unworthy of respect and sympathy.

Many cases of this description might be found “Whitechapel way,” by those who have the time, energy and desire to seek them out. It will always be found that those who have the best claim to help and succour are the last to seek out for themselves the assistance that they should receive. It is only by accident that such cases are discovered, and hence my belief that time spent amongst the poor themselves is far more productive of good and permanent results, than liberal subscriptions given to institutions of which the donor knows no more than can be gleaned from the hurried perusal of an abbreviated prospectus. In this manner Dickens acquired his marvellous stores of material and knowledge of the people. Exaggerated as some of his characters may seem, their prototypes are constantly coming on the scene, and as I talked to “Hookey” it seemed as if the shade of Captain Cuttle had penetrated the wilds of Whitechapel.

To be honest, examining the picture, I cannot discern the “painful existence” of the woman from her “troubled expression” with “unquestionably accuracy” (as Thomson and Smith intended), though I was not there when the photograph was taken to learn the full story. It would be easy to distance ourselves from this pitiful tale of “Hookey Alf” by dismissing it as illustrative of the world before employers’ liability and incapacity benefits, yet it remains a common sight today to see people with visible disabilities on the streets of East London who are either begging or selling the Big Issue.

I respect Adophe’s engagement with “Hookey Alf’s” feelings of frustration, humiliation and desperation, drawing the reader to empathise with his subject, creating a sympathetic portrait that anyone with an ounce of humanity can recognise. Significantly, Dickens is the touchstone when it comes descriptions of the common people of London. And I feel that Adophe is evangelically persuasive in arguing the case for the moral integrity of the man to refute a contrary voice that, like Ebenezeer Scrooge, is condemning the poor as feckless and irresponsible.

Most interesting and radical is Adolphe’s proposal to his educated readers that they might actually consider spending time among the poor, engaging directly with their fellow humans, rather than merely making charitable donations to salve their guilt. Living in the city, it is hard not to become inured or indifferent to those who ask for money in the street, but Adolphe Smith’s article speaks across more than a century to remind us, if we should need it, that “those who resort to the humblest ways of making money in the street are not always unworthy of respect and sympathy”.

Hullabaloo at the Thrift Store

One Saturday morning recently, I was walking down Brick Lane when I saw a long line of hundreds of excited young people that stretched the entire length of Sclater St. When the Thrift Store decided to post an invitation to their jumble sale on facebook, they never dreamed that over two and a half thousand people would arrive, many coming from as far away as Oxfordshire and Cambridgeshire. At opening time there was already a queue of four hundred people waiting outside but during the morning it grew and grew, until the line reached all the way round the corner into Brick Lane. You have to admit it was a good deal, for £10 you could fill a small bag with as many clothes as you pleased or for £20 you could fill a big bag.

There are so many reasons to love thrifting but I had no idea the culture of secondhand was this huge – until I saw the line of enthusiasts in Sclater St, all dressed in their diverse individual styles created from vintage. Spitalfields is now the capital of this culture and thousands of eager people come every weekend from all over, to trawl through the different thrift stores side by side on Brick Lane, Cheshire St and Sclater St. Taking the occasional break for coffee or lunch, and meeting up with friends along the way, it is a pleasant day’s occupation. I see them parade back to Liverpool St clutching their bags triumphantly at the end of the afternoon.

Quite simply, vintage clothes have brought the fun and creativity back to fashion because they are cheap and every item is unique. With tantalising ambiguity, these clothes manage to be both democratic and exclusive simultaneously, permitting everyone to create a distinctive look, expressive of their personal identity, that no-one else has or can have. And the alterations that are often required invite the purchaser to restyle the garments, using second-hand to become fashion-forward. Another attraction is that old clothes often display higher quality workmanship and are manufactured from better fabric than many new clothes.

I love the poetry of old clothes that carry their history, of design, of manufacture, of the previous owner, and of other times and other worlds. There is a fascinating dynamic present when a younger generation take on the garments of a previous generation, subtling adjusting them to the suit the requirements and expectations of contemporary life. We wear them differently. In their form and structure, these clothes connect the wearer to the social custom of the past while revealing how the world has changed too.

For those politically aware fashionistas, wearing secondhand clothes is an ethical statement in itself, and one of the best kinds of recycling, providing the easiest path to the moral high ground that I know. Because you are conserving the resources that would be used to make new clothes and also dissociating yourself from the exploitative labour practices of the High St stores. Imagine, all this integrity that can be acquired just by purchasing some old rag!

Each month, the East End Thrift Store holds a lively shopping party with a free bar at their vast warehouse in Whitechapel. Once I heard about it, I realised this was an opportunity too good to be missed. So last week, photographer Sarah Ainslie and I went along to investigate. We hoped to photograph some extravagant wild flowers to show you, but instead of a bunch of secondhand roses, we discovered these raging beauties…

Poppy is thinking about whether to buy this silver hat for £10.

Duke knows how to look good in primary coloured sweaters.

This is Nimi and Tina, showing off the snazzy red dress she discovered for £15.

This is Jen, triumphant with the classic shirtdress she found for £30.

This is Rafal who knows instinctively how to carry off a cape.

This is Nina delighted with the nautical-themed shiftdress she will wear all summer long.

This is Paula and Ainara who are going to share this jacket.

This is Robson, an artist and curator, looking for an outfit for the opening of his show on Thursday.

Emma is deliberating between a red dress and this one in deep turquoise for £30.

Max has just moved to London from Weymouth and is considering investing in a leather jacket, maybe.

All pictures copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Nina Bawden, novelist

In recent years, a recurring highlight in my existence has been the opportunity to walk from Spitalfields through Hoxton and along the canal path up to Islington to enjoy a light lunch with the sublimely elegant novelist Nina Bawden, who lives in an old terrace backing onto the canal and whom I consider it a great honour to count as my friend. I first met Nina when I took my copy of “Carrie’s War” along to a bookshop and queued up with all the hundreds of other children to have it signed by the famous author. She appeared to my child’s eyes as the incarnation of adult grace and authoritative literary intellect, and it is an opinion that I have had no reason to qualify, except to say that my estimation of Nina has grown as I have come to know her.

Years after that book signing, Kaye Webb, Nina’s editor who had encouraged my own nascent efforts at writing, rang me up at six-thirty one evening to say she had just remembered Nina and her husband Austen Kark were coming to dinner that very night and she had nothing to give them. At this time Kaye was over eighty and housebound, so I sprinted through the supermarket to arrive breathless at Kaye’s flat beside the canal in Little Venice by seven-thirty – and when Nina and Austen arrived at eight, dinner was in the oven.

They were an impressive couple, Austen (who was Head of the BBC World Service) handsome in a well-tailored suit and Nina, a classically beautiful woman, stylish in a Jean Muir dress. I regret that I cannot recall more of the evening, but I was working so hard to conceal my anxiety over the hasty cuisine that I was completely overawed. Naturally, in such sympathetic company, it all passed off smoothly and I only revealed the whole truth to Nina last year when Valerie Grove was writing her biography of Kaye Webb, “So Much to Tell,” to be published by Penguin in May.

Given the background to our friendship, it has been my great delight to get to know Nina a little better since we became “neighbours” on this side of London and I was thrilled when she consented to my writing this pen portrait, celebrating the occasion of her recent nomination for the Lost Booker Prize of 1971 for her novel “The Birds on the Trees” which has just been republished by Virago. When a journalist from The Times rang Nina to ask what “The Birds on the Trees” was about, Nina pulled a copy from her shelves, where it had sat since 1971, crowded among all her other works in her peaceful study at the back of the house overlooking the garden, and read it to find out. “You do learn as you go on,” admitted Nina to me, “so I expected bad bits but I wasn’t displeased as I expected.” Adding rhetorically, “Who was it who said,’We write novels so we have something to read when we are old?'”

Born in East London in 1925, Nina was evacuated during the blitz and then became amongst the first of her post-war generation to go up to Oxford. At Somerville College, she had the temerity to attempt to persuade fellow undergraduate Margaret Thatcher (Margaret Roberts as she was then) to join the Labour Party, that enshrined the spirit of egalitarianism which defined those years. Even then, young Margaret displayed the hard-nosed pragmatism that was her trademark, declaring that she joined the Conservatives because they were less fashionable and consequently, with less competition, she would have a better chance of making it into parliament.

The catalogue of Nina’s literary achievement, which stretches from the early fifties into the new century, consists of over forty novels, twenty-three for adults and nineteen for children. A canon that is almost unparalleled among her contemporaries and that, in its phenomenal social range and variety, can be read as an account of the transformation brought about by the idealistic post-war culture of the Welfare State, and of its short-comings too.

Nina met Austen, the love of her life, by chance on the top of a bus in 1953 when they were both in their twenties and married to other people. They both divorced to remarry, finding happiness together in a marriage that lasted until Austen’s death in 2002. At first,they created a family home in Chertsey, moving in 1979 to Nina’s current home in Islington, when it was still an unfashionable place to live. Although her terrace is now considered rather grand (Boris Johnson lives a stone’s throw away), Nina told me she understood they were originally built for the servants and mistresses of those who lived on the better side of Islington.

Nina is someone who instinctively knows how to live, and through her persistent application to the art of writing novels and in her family life with Austen and their children, she won great happiness and fulfillment. I know this because I sense it in her bright spirit and powerfully magnanimity, but equally I know that her life has been touched with grief and tragedy in ways that give her innate warmth and generosity an exceptional poignancy. When Nina reread “The Birds on the Trees”, she discovered it had been inspired by the suicide of her son Nicky, “When bad things happen, you absorb them into yourself and make use of them in novels.” she said soberly, “In the case of Austen, I had a fight with the railways.”

On 1oth May 2002, Nina and Austen boarded a train at Kings Cross to got to Cambridge for a friend’s birthday party. They never arrived. The train derailed at over one hundred miles an hour and Nina’s carriage detached itself, rolling perpendicular to the direction of travel and entering Potters Bar station to straddle the platforms horizontally. Austen was killed instantly and Nina was cut from the wreckage at the point of death, with every bone in her body broken. In total, seven people died and seventy were injured that day.

After multiple surgeries and, defying the predictions of her doctors, Nina stood up again through sheer willpower, walked again and returned to live in the home that she had shared with Austen. In grief at the loss of Austen and no longer with his emotional support, Nina found herself exposed in a brutally politicised new world, “I suppose I am lucky to have lived so long believing that most men are for the most part honourable. And lucky to have taken a profession in which owning up and telling the truth is rarely a financial disadvantage” she wrote. Nothing in her experience prepared her for the corporate executives of the privatised rail companies who refused to admit liability or even apologise in case their share price went down. It was apparent at once that the crash was caused by poorly maintained points as the maintenance company had cut corners to increase profitability at the expense of safety, but they denied it to the end.

Refused legal aid by a government who for their own reasons deemed the case of the survivors seeking to establish liability as “not in the public interest”, it was only when Nina stepped forward to lead the fight herself, setting out to take the rail companies to the High Court personally, that they finally admitted liability. If Nina had lost her case, she risked forfeiting her home to pay legal costs. But after losing so much, inspired by her love for Austen, Nina was determined to see it through and, in doing so, she won compensation for all the survivors.

You can read Nina’s own account of this experience in “Dear Austen”, a series of letters that she wrote to her dead husband to explain what happened. “When we bought tickets for this railway journey we had expected a safe arrival, not an earthquake smashing lives into pieces,” wrote Nina to Austen,“I dislike the word ‘victim’. I dislike being told that I ‘lost’ my husband – as if I had idly abandoned you by the side of the railway track like a pair of unwanted old shoes. You were killed. I didn’t lose you. And I am not a victim, I am an angry survivor.”

Sometimes extraordinary events can reveal extraordinary qualities in human beings and Nina Bawden has proved herself to be an extraordinary woman, remarkable not only as a top class novelist, but also as a woman with moral courage who risked everything to stand up for justice. It is one thing to write as a humanitarian but is another to fight for your beliefs when you are at your most vulnerable – this was the moment when Nina transformed from writer to protagonist, and became a heroine in the process. Nina may not look like an obvious heroine because she is so fragile and retiring, but her strength is on the inside.

Whenever I visit Nina, my sanity is restored. I walk home to Spitalfields along the canal and the world feels a richer place as I carry the aura of her gentle presence with me. Concluding our conversation in the study last week, before we went downstairs to enjoy our lunch, Nina smiled radiantly and said, ” I’ve decided to get on with my novel…” in a line that sounded like a defiant challenge to the universe.

Hugo Glendinning, photographer

This is the unforgettable moment when the rock chicks of the Speed Angels (the world’s first trans-sexual pop group) took Spitalfields by storm, caught on film by photographer Hugo Glendinning who lived at 27 Fournier St when he took this picture. For nearly twenty-five years, Henry Barlow, the owner of this magnificent eighteenth century house, let it out to a lucky group of young actors and artists at rents they could afford, until it was sold this year. When Hugo arrived in 1989, he was just three years into his career but by the time he moved out in 2002, after more than a decade of ceaselessly inventive and stylish photography, he had achieved a reputation as one of the most distinguished and prolific photographers in the sphere of theatre and dance.

All the photographs shown here were taken by Hugo using 27 Fournier St as his location. And the location fees for these shoots covered the electricity and gas bills for years – even though it is a large old house and expensive to heat. So in return for accepting the occasional invasion by trans-sexual rock chicks and other extravagant glamorous personalities, the residents of 27 Fournier St were able to remain warm all winter. Speaking as someone who collects broken pallets in the street to chop up for firewood, this sounds like a very good deal to me.

Each of these superlative pictures were commissions for major publications, work that Hugo undertook in addition to his performing arts photography. When I met with Hugo in his studio last week, we thought it would be amusing to show you these photographs because collectively they tell a different story from their original intention. Many people have speculated about the stories that this sedate old house could tell but I do not think anyone ever imagined the scenarios pictured here.

Even though these photo shoots were undertaken years apart, I cannot resist imagining them all happening simultaneously, as some kind of phantasmagoric party at 27 Fournier St. They propose a bizarre game of consequences in which the Speed Angels encounter Patrick Stewart, better known as Jean-Luc Picard, the Captain of the Star Ship Enterprise, in a time-warp in which Amelia Fox is dressed up for a costume drama (looking as if she might be one of the original residents from the early eighteenth century), while the high-flying Fuel Design team cavort in the back garden, and maverick dancer and choreographer Nigel Charnock takes a bath to promote AIDS awareness.

Hugo’s innovative panoramic photography takes a step further in permitting the architecture of 27 Fournier St to become an integral part of the drama, metamorphosing into a theatrical landscape heaving with surreal possibilities. In fact, digital manipulation permitted Hugo to twist and reconfigure the house to become as labyrinthine as the Topkapi Palace. These panoramas present a compositional challenge to a photographer that is closer to narrative painting than to conventional photography. Although in Hugo’s case, he was placing figures within his own personal domestic space, which may account, in part, for the graceful accomplishment of these notable examples of the genre. You might like to click on each of the panoramas below to enlarge them so you can examine all the nooks and crannies of the old house in detail.

The first panorama is an elegant group portrait of a whole generation of young women artists photographed in the ground floor living room at 27 Fournier St in 1997. You will recognise Tracey Emin, who is a neighbour in Fournier St, perched on top of the television set, but how many others can you identify? The next eight panoramas were the result of Hugo’s collaboration with Forced Entertainment Theatre Company, entitled “Frozen Palaces” and shot in the house over a single weekend as a very early Quick Time Virtual Reality project. Conceived by Forced Entertainment as “a landscape of interlocking dreams, these images allowed the viewer to explore, view or investigate – in an experience akin to wandering, or trying out versions of the truth and of making playful connections.” I am fascinated by these enigmatic melodramas, an unlikely combination of eighteenth century architecture and the technology of virtual reality, as a means to unlock the dream life of the old house. Finally, you can see one of Hugo’s witty “Chill in tonight” series of panoramic advertisements that he shot for Guinness. Once they were posted around the East End, Hugo ran out with his camera to photograph his own pictures on billboards and enjoy the secret irony of these private interiors visible in the public arena. The one pictured here shows Hugo’s living room in 27 Fournier St on display in Old St.

Scattered across different publications at different times, no-one would ever have made the connection that unifies these diverse photographs but, seen together, this set of pictures illustrates just how inspiring a single charismatic architectural space can be, for a photographer with such an exceptionally fertile imagination as Hugo Glendinning.

All photographs copyright © Hugo Glendinning

I am grateful to Hugo Glendinning for permitting me to use a detail of a photograph he took of the Market Cafe in Fournier St on the day it closed down, as the header for the month of March. In this picture, the passersby are reading the notice announcing the closure. I look forward to showing you more of the pictures Hugo took during his time in Spitalfields at a later date.

Columbia Road Market 24

I woke in the night several times to the sound of rain falling and, sure enough, I found myself walking up the road to the market in the wet early this morning. The market was the emptiest I ever saw it, with just the stallholders huddling under their canopies clutching cups of hot tea after a long night, loading their vans, travelling and setting up in the pouring rain. I was admiring all the additional herbs on sale this week, when I saw the herb women shivering and congratulated them on their courage in making it here. “We’ve got no choice, this is our living,” they replied brightly, “Let’s hope we get some brave customers today!”

Certainly, the prices were as ridiculous as the weather, with cut flowers at four bunches for a fiver. Anyone that braves the rain today can buy armfuls of flowers for just a few pounds. I bought four pots of tiny lustrous Aconites (Eranthis hyemalis) for £5 and replanted them in this bowl to place on my old dresser, continuing the display of plant life that I have maintained through the Winter while I await the Spring flowers in my garden.