At Waterbeach

Tickets are available for my walking tour now

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

I set out to visit the intriguingly named Waterbeach and Landbeach in Cambridgeshire with the object of viewing Denny Abbey. Built in the twelfth century as an outpost of Ely Cathedral, it passed through the hands of the Benedictine Monks, the Knights Templar and a closed order of Franciscan nuns known as the ‘Poor Clares’ – all before being converted into a private home for the Countess of Pembroke in the fifteenth century. Viewed across the meadow filled with cattle, today the former abbey presents the appearance of an attractively ramshackle farmhouse.

A closer view reveals fragments of medieval stonework protruding from the walls, tell-tale signs of how this curious structure has been refashioned to suit the requirements of diverse owners through time. Yet the current mishmash delivers a charismatic architectural outcome, as a building rich in texture and idiosyncratic form. From every direction, it looks completely different and the sequence of internal spaces is as fascinating as the exterior.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the property came into the ownership of the Ministry of Works and archaeologists set to work deconstructing the structure to ascertain its history. Walking through Denny Abbey today is a vertiginous experience since the first floor spaces occupy the upper space of the nave with gothic arches thrusting towards the ceiling at unexpected angles. Most astonishing is to view successive phases of medieval remodelling, each cutting through the previous work without any of the reverence that we have for this architecture, centuries later.

An old walnut tree presides over the bleached lawn at the rear of the abbey, where lines of stone indicate the former extent of the building. A magnificent long refectory stands to the east, complete with its floor of ancient ceramic tiles. While the Farmland Museum occupies a sequence of handsome barns surrounding the abbey, boasting a fine collection of old agricultural machinery and a series of tableaux illustrating rural trades.

Nearby at Landbeach, I followed the path of a former Roman irrigation system that extends across this corner of the fen, arriving at the magnificent Tithe Barn. Stepping from the afternoon sunlight, the interior of the lofty barn appeared to recede into darkness. As my eyes adjusted, the substantial structure of purlins and rafters above became visible, arching over the worn brick threshing floor beneath. Standing in the cool shadow of a four hundred year old barn proved an ideal vantage point to view the meadow ablaze with sunlight in this exceptional summer.

Denny Abbey, Waterbeach

Mysterious stone head at Denny Abbey

The Farmland Museum, Waterbeach

Tithe Barn, Landbeach

You may also like to read my other story about Waterbeach

Julius Mendes Price’s London Types

Click to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

It is my delight to show these examples of London Types, designed and written by the celebrated war artist Julius Mendes Price and issued with Carreras Black Cat Cigarettes in 1919. These are among the favourites in my ever-growing collection of London Street Cries down through the ages. Almost all are men and some of these images – such as the cats’ meat man – are barely changed from earlier centuries, yet others – such as the telephone girl – are undeniably part of the modern world.

CLICK TO BUY A COPY OF CRIES OF LONDON FOR £20

You may also like to take a look at these other sets of the Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

Dee Tocqueville, Lollipop Lady

Click to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS this Saturday

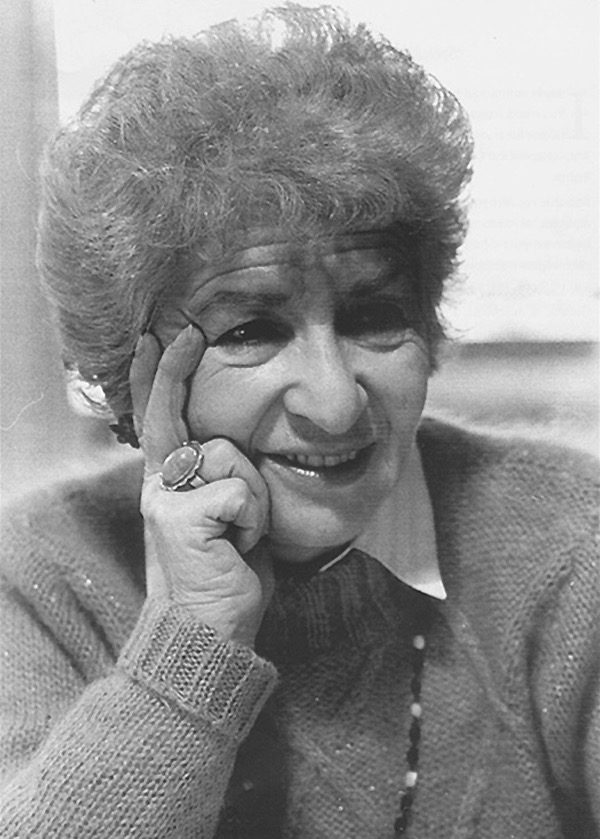

Cordelia Tocqueville

Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I made the trip over to Leytonstone to pay homage to Cordelia – known as ‘Dee’ – Tocqueville, the undisputed queen of East End Lollipop Ladies, who has been out on the street pursuing her selfless task every day, come rain or shine, for as long as anyone can remember. “I took the job at first when my daughter was small, because she was at the school and I could be at home with her in the holidays,” Dee admitted to me, as she scanned the road conscientiously for approaching cars,“Though after the first winter in the rain and cold, I thought, ‘I’m not sticking this!’ but here I am more than forty years later.”

Even at five hundred yards’ distance, we spotted Dee Tocqueville glowing fluorescent at the tricky bend in Francis Rd where it meets Newport Rd outside the school. A lethal configuration that could prove a recipe for carnage and disaster, you might think – if it were not for the benign presence of Dee, wielding her lollipop with imperial authority and ensuring that road safety always prevails. “After all these years, I’m part and parcel of the street furniture,” she confessed to me coyly, before stepping forward purposefully onto the crossing, fixing her eyes upon the windscreen of an approaching car and extending her left hand in a significant gesture honed over decades. Sure enough, at the sight of her imperial sceptre and dazzling fluorescent robes the driver acquiesced to Dee’s command.

We had arrived at three, just before school came out and, over the next half hour, we witnessed a surge of traffic that coincided with the raggle-taggle procession of pupils and their mothers straggling over the crossing, all guaranteed safe passage by Dee. In the midst of this, greetings were exchanged between everyone that crossed and Dee. And once each posse had made it safely to the opposite kerb, Dee retreated with a regal wave to the drivers who had been waiting. Just occasionally, Dee altered the tone of her voice, instructing over-excited children at the opposite kerb to “Wait there please!” while she made sure the way was clear. Once, a car pulled away over the crossing when the children had passed but before they had reached the other side of the road, incurring Dee’s ire. “They’re impatient, aren’t they?” she commented to me, gently shaking her head in sage disappointment at human failing.

Complementing her innate moral authority, Dee is the most self-effacing person you could hope to meet.“It gives you a reason to get up in the morning, and you meet lots of people and make lots of friends,” she informed me simply, when I asked her what she got out of being a Lollipop Lady. Dee was born and grew up fifty yards away in Francis Rd and attended Newport Rd School as a pupil herself, crossing the road every day, until she crossed it for good when she married a man who lived a hundred yards down Newport Rd. Thus it has been a life passed in the vicinity and, when Dee stands upon the crossing, she presides at the centre of her personal universe.“After all these years I’ve been seeing children across the road, I have seen generations pass before me – children and their children and grandchildren. The grandparents remember me and they come back and say, ‘You still here?'” she confided to me fondly.

At three-thirty precisely, the tumult ceased and the road emptied of cars and pedestrians once everyone had gone home for tea. Completing her day’s work Dee stowed the lollipop in its secret home overnight and we accompanied her down Newport Rd to an immaculately-appointed villa where hollyhocks bloomed in the front garden. “I have rheumatism in my right hand where the rain runs down the pole and it’s unfortunate where I have to stand because the sun is in my eyes,” she revealed with stoic indifference, taking off her dark glasses once we had reached the comfort of her private den and she had put her feet up, before adding, “A lot of Boroughs are doing away with Lollipop Ladies, it’s a bad thing.” In the peace of her own home, Dee sighed to herself.

The shelves were lined with books, evidence of Dee’s passion for reading and a table was covered with paraphernalia for making greetings cards, Dee’s hobby. “People don’t recognise me without my uniform,” she declared with a twinkle in her eye, introducing a disclosure,“every Thursday, I go up to Leyton to a cafe with armchairs, and I sit there and read my book for an hour with a cup of coffee – that’s my treat.” Such is the modest secret life of the Lollipop Lady.

“When my husband died, I thought of giving it up,” Dee informed me candidly, “but instead I decided to give up my evening cleaning job for the Council, when I reached seventy, and keep this going. I enjoy doing it because I love to see the children. One year, there was an advert on the television in which a child gave a Lollipop Lady a box of Cadbury’s Roses and I got fifteen boxes that Christmas!”

“After all these years, I’m part and parcel of the street furniture”

Dee puts her feet up in the den at home in Newport Rd

Dee with her brother David in 1959 outside the house in Francis Rd where they grew up

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to take a look at

Lorna Brunstein Of Black Lion Yard

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS this Saturday

Lorna with her mother Esther in Whitechapel, 1950

In this photograph, Lorna Brunstein is held by her mother outside Fishberg’s jewellers on the corner of Black Lion Yard and Whitechapel Rd. It is a captivating image of maternal pride and affection that carries an astonishing story. The tale this tender photograph carries is one of how this might never have happened and yet, by the grace of fortune, it did.

I met Lorna upon her return visit to Whitechapel where she grew up the early fifties. Although she left Black Lion Yard at the age of six, it is a place that still carries great meaning for her even though it was demolished forty years ago.

We sat together in a crowded cafe in Whitechapel but, as Lorna told me her story, the sounds of the other diners faded out and I understood why she carries such affection for a place that no longer exists beyond the realm of memory.

“My relationship with the East End goes back to when I was born. I have scant memories, it was the early years of my childhood, but this was the area where I spent the first six years of my life. I was born in Mile End maternity hospital in December 1950.

Esther, my mother came to London in 1947. She was liberated from Belsen in April 1945 and she stayed in their makeshift hospital to recuperate for a few months. She had been through Auschwitz and lost all her family, apart from one brother who survived (though she did not know it at the time).

In the summer of 1945 she was taken to Sweden, to a place she said was beautiful – in the forest – where she and many others were looked after. It was while she was in Sweden that she and her brother Perec discovered via the Bund ( Polish Jewish workers Socialist party) that they had both survived. Esther was the youngest of three and Perec was the middle child. Their surname was Zylberberg, which means silver mountain. He was one of the boys who was taken to Windermere from Theresienstadt at the end of the War. They each wrote letters and confirmed that the other had survived. Esther had last seen Perec in March 1944.

After a few months in Windermere, he went to London and his sole mission was to get Esther over. That was all she wanted to do too, but it took two years from 1945 to 1947 for a visa to be granted. So not much has changed really. She was seventeen years old, had lost her mother at Auschwitz and her teenage years yet she was not allowed to come into the country unless she had a job, an address, and the name of a British citizen to be her guarantor and sponsor.

Maurice Regen (Uncle Moishe as I knew him) was an eccentric yet kind man. He came to London in the twenties from Lodz, which was my mother’s hometown. He and his wife were elderly, they had no children and lived in Romford. He said, ‘She can live in our house, so she will have an address, and she can be our housekeeper, that will be her job, and she won’t be dependent on the state.’ That was how my mother came over. My Uncle Perec met her and I think Uncle Moishe was probably there at Tilbury too.

She lived in Romford but she met Stan, my father, at the Grand Palais Yiddish Theatre in Whitechapel where she was acting — her Yiddish was brilliant – and he was the scenic designer. He was an artist from Warsaw. He fled at the beginning of the War and was put in a labour camp in Siberia after spending fourteen months of solitary confinement in a prison in the Soviet Union. His story was pretty horrific too. He was an only child, and he lost everyone, his entire family. He was thirteen years older than my mother.

Stan also came to London in 1947. At the end of the War, he ended up in Italy. The Hitler/Stalin pact was broken while he was in Siberia and he was freed when the political amnesty was declared, so he joined up with the Polish Free Army under General Anders — as many of them did — and fought at the Battle of Monte Casino. Afterwards, he was in Rome for two years, studying scenic design at the Rome Academy of Fine Arts.

So my mother and father met in 1947 or 1948. I do not know exactly when. They got married in 1949 and I was born in 1950. They lived in a little flat in Black Lion Yard in Whitechapel until they moved to Ilford.

Rachel Fishberg – known as Ray – was really significant in my life and my parents’ life, my mother in particular. Ray was an old lady who became a surrogate grandma to my sister – who is four years younger – and me. We remember her with such affection. The Fishbergs were jewellers and were reasonably wealthy among Jewish people in the East End at that time. Ray ran her husband’s and his father’s jewellery shop, on the corner of Whitechapel Road and Black Lion Yard. I remember going back and visiting it when I was six, after we moved out.

My parents had no money, so grandma Ray Fishberg said they could live in the flat above the shop. At the time, they had nothing. My father could not live on his art and he took a diploma in design, tailoring and cutting at Sir John Cass School of Art in Aldgate. He designed and made children’s clothes on a sewing machine in the room we lived in and sold them in the market, and that was how we got by. Grandma Ray let them live there – probably for nothing – and, in fact, she paid for their wedding. When they got married in 1949 in Willesden Green, she paid for the wedding dress.

In 1957, when I was six, we moved to Ilford because my parents did not want to stay in the East End. She gave them the deposit for their first house. She was a lovely lady and she enabled them to have a start a life. This is why I feel so connected to this place, even though my memories of actually living here are scant.

I have this one memory of being in a pram, or maybe a pushchair, and feeling the sensation of the wheels on the cobbles in Black Lion Yard, going to the dairy — my mother said it was Evans the Dairy at the end of the Yard — to get milk.

Apparently, I went Montefiore School in Hanbury Street and I remember my mother talking about Toynbee Hall, where there were meetings, and taking me in the pram to Lyons Corner House in Aldgate where there was this chap, Shtencl, the poet of the East End.

He was quite an eccentric person who wandered around the streets and my mother told me he called into Lyons Corner House when she was sitting there with me as a baby. She said he stroked my head and said, ‘Sheyne, sheyne,’ which in Yiddish is ‘beautiful.’ My mother was in awe of him because his Yiddish was so brilliant and Yiddish was the language so dear to her heart. I was anointed by him even though I have no memory of him.

My mother and father talked a lot about Black Lion Yard. They said, on Sunday mornings at the entrance to Black Lion Yard where the pavement was quite deep, employers and potential employees in the tailoring ‘shmatte’ trade would gather and connect. That was what my father was doing then. He would stand there on a Sunday morning to get work.

Those were the founding years of my life. I have a deep affection for this place because for my parents – even though they wanted to leave for a better life – it was where they found sanctuary. My father used to say, ‘Thank goodness I’m here, I’ve finally found a place where I am able to walk down the street without having to look over my shoulder.”

Black Lion Yard, early seventies, by David Granick

Steps down to Black Lion Yard by Ron McCormick

Lorna aged eight

Esther & Stan Brunstein in the seventies

Esther Brunstein

Stan Brunstein

You may also like to read about

The Cries Of London

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS this Saturday

I am giving an illustrated lecture about THE CRIES OF LONDON as a prologue to Berio’s CRIES OF LONDON performed by the Carice Singers at St Botolph’s Without Bishopsgate on Tuesday 2nd July at 6:30pm as part of SPITALFIELDS MUSIC FESTIVAL. Click here to book your ticket

It is my delight to show you this tiny anonymous pamphlet no larger than a folded banknote entitled simply THE CRIES OF LONDON. More than two centuries old, it is one of innumerable publications on this subject down through the ages and consequently only of little monetary worth. Yet, to me, this shabby rag is one of my favourites in the series because of the modesty of its production. The stained pages evidence its fond usage by those who, once upon a time, actually saw these mythic characters upon the streets of London.

You may also like to take a look at these other sets of the Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

More Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

Hester Mallin, Artist

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS this Saturday

Langdale St leading to Cannon St Rd

Like the princess in the tower, when I met her in the last year of her life at ninety-one years old, Hester Mallin was confined to her flat on the top floor of a tall block off the Roman Rd in Bow, where I had the privilege of visiting and hearing her story. From this lofty height, Hester contemplated the expanse of her time in the East End. Born to parents who escaped Russia early in the last century, Hester spent the greater part of her life in Stepney, where she grew up in the close Jewish community that once inhabited the narrow streets surrounding Hessel St.

Of independent mind and down-to-earth nature, Hester took control of her destiny at thirteen and plotted her own path through life ever after. When the Stepney streets where her parents’ sought their existence emptied as residents left to seek better housing in the suburbs and demolition followed, Hester could not bear to see this landscape – which had such intense personal meaning – being erased. So she began to photograph it.

Decades later, when her photographs were all that remained, Hester transformed these images, coloured by memory, into the haunting, austere paintings you see here. Of deceptive simplicity, these finely wrought watercolours of subtly-toned hues were emotionally charged images for Hester. Even if the streets and buildings are gone and even if Hester could never go back to her childhood territory, she had these paintings. She kept them safely beside her bed to cherish as the only record of the place which contains her parents’ lives, their community and their world, which have now all gone completely.

In later years, Hester discovered a talent as a gardener, celebrated for her flair at high-rise gardening, exemplified by her thirty-five foot balcony garden on the twenty-third floor in Bow, where the great and the good of the horticultural world came to pay homage to Hester’s achievements. Feature coverage and television appearances brought Hester international fame and demands for lectures, including a trip to the Falkland Isles to inspire the troops with horticultural aspirations.

Yet in spite of her remarkable life and resources of creativity, Hester modestly considered herself a ‘typical East Ender’ – as she confided to me.

“I never got married and had children. In my experience, marriage for the working class girl was horrible. If she was unlucky, she met a man who she thought was nice, she would marry and he would change and become a wife beater. It was not for me. I saw so much of it. I thought ‘I’d rather stay single than get beaten up every time my husband gets drunk, Jewish or not.’ It never appealed to me. I never wanted to be married. Other people wanted to marry me but I never wanted to be married.

My father, Maurice Smolensky, came in his early twenties from Lomza which is part of Poland now and I think my mother came from Russia too, but I am not quite sure. Her name was Rachel Salzburg – what was she doing with a German sounding name like that?

It was very sad, she was sent on her own at fourteen years old. Can you imagine? A very beautiful young girl, illiterate, speaking no English and knowing nothing. There must have been a reason why they chucked her out to England. She was in terrible danger. She stood staring in bewilderment and grief. This was the time of the white slave trade when young girls were packed off to South America to be prostituted, yet she was luckyecause there was a gang of Jewish men looking out at the port in London. If they saw any young girl travelling alone, they would ask ‘Have you been sent?’ They would look after these girls and this is what happened to Rachel, my mother. They took her to the Jewish shelter in Aldgate and from there she spent a bewildering youth, working as a servant when she could get work. She was always pure. Poor girl. She was beautiful, with blonde teutonic looks.

Apparently, her family came to the East End years later and she was in touch with them but only loosely. There must have been some big family goings-on, but I know not. They were bombed out of their house in Sutton St, off Commercial Rd, and disappeared, they did not take her. There must have been a falling-out.

My father was a journeyman baker, who learnt his trade in Russia where, apparently, his father owned a mill. He worked in all the local bakeries around Hessel St, Christian St, Fairclough St – all those adjacent streets in Stepney where there were lots of little Jewish baker’s shops. He worked in the basements.

My parents were put together by a Jewish matchmaker, that was how they met.

At Raynes Foundation School, when I drew, my teacher used to say I was copying it from somewhere – but where would I copy it from? I remember we were all asked to draw a biblical scene. So I drew a picture of Moses leading his people out into the desert in chalk, with all these figures disappearing into the distance led by Moses with a long stick. I remember it clearly, the teacher stormed over to my desk and said, ‘Where did you get this from?’ Of course, I was flummoxed, I did not know what she was talking about so I could not answer. ‘No answer!’ she said, ‘You didn’t draw this.’ I was a shy child, I was absolutely silenced and defeated. That was my introduction to Art.

I grew up in Langdale St Mansions, a block of two hundred flats of the slum variety and almost entirely occupied by Jewish people. It was horrible but my mother was exceptionally clean, she was fighting dirt all the time. I had a brother, Harry, he died a few years ago. He turned Left and became Communist, and that wrecked everything. He was lured into it by shameful people.

My mother was a brave, brave woman. She went along to the Battle of Cable St to see what was going on. She was an amazing lady. When she came back, I asked ‘What was it like?’ but she would not answer me. It was obviously horrible. Even though she was illiterate, my mother knew what was happening in the world. Jewish people felt under threat.

I left school at thirteen and a half just as the war began. Nobody bothered about me because they were doing their own thing. I found any old job – odds and ends of work in an office for six months. Then I started as an Air Raid Precautions messenger girl but that was not good enough for me – it was not dangerous enough – so I decided I wanted to be warden. I persisted and I became Britain’s youngest Air Raid Warden. I chose to do it because I wanted to do my bit and it was interesting because there was always action – Stepney was bombed and bombed and bombed. People got used to the sight of this little girl in warden’s uniform. I was not frightened, I was excited.

Some of the elderly Jewish men who were too old for the armed services would come with me and we would stroll through the streets with bombs falling all around us. Our job was shutting doors. Street doors would pop open every time a bomb fell and we would put out a hand and shut it, and on the way back we would shut the same door again. There was a lot of looting going on.

Towards the end of the war, I was moved into doing office work for Stepney Borough Council on the corner of Philpot St and Commercial Rd. It brought some money into the house and relieved my poor dad. He worked like a slave and died of overwork at seventy-one. He worked all night.

I taught myself photography, I am a self-taught woman – an autodidact polymath. During the war, I realised the houses were all going, so I started to photograph them. I thought, ‘Why aren’t more people doing this?’ I photographed architecture and out of my photographs came my paintings. The houses were being pulled down and I wanted to make a permanent record. So I took a lot of photographs and later on I thought, ‘That would make a good subject for painting.’ It was one of those things, I just started painting because it attracted me. I never went out in the street and did paintings, some are from photographs and some are from memory. I never exhibited my work.

I worked at the council until I was sixty when I retired because I wanted to concentrate on gardening and painting. I always wanted a garden when I was a child growing up in that slum flat on the fourth floor of hideous Langdale Mansions. I do not know how I knew, but I just knew I wanted plants. I never learnt about plants, it was instinctive for me. I used to buy seeds and little plantlets.

In 1980, I moved into this tower block and there was an opportunity to create a thirty-five foot long balcony garden. I looked for plants that were low maintenance, wind resistant, needed little watering and did not grow too big. I had to teach myself and learn by experiment. I did many exhibitions of my gardening including one at Selfridges. I did the whole thing myself.

I am always asked the same question, ‘Why do you speak so nicely?’ I do not know why I speak as I do. I listen to myself and I think ‘Where did you get that phrase from?’ I am self-educated, I have read a lot but anyone can do that. I am not a feminist, feminists have many faults and can be as vicious as anyone else.

I have always lived in Stepney, not by choice – it was just one of those things. I always lived in slum flats until this one. I am a typical lifelong East Ender of the old kind, I have never lived anywhere else.”

Entrance to Langdale St

Cannon Street Rd

Burslem St Shops (Demolished 1975)

Rear of Morgan Houses, Hessel St

Hessel St

Hessel St leading to Commercial Rd

Wicker St Flats

“The idea of making a garden on the topmost twenty-third floor of a council tower block in East London might be compared with a brave, but astonishingly foolhardy attempt to make a garden in a crow’s nest of an old fashioned sailing ship” – Hester Mallin, 1980

Hester Mallin & Joe Brown in 1988

Hester’s father Maurice Smolensky stands centre in this photograph taken early in the last century

Paintings copyright © Estate of Hester Mallin

You may also like to take a look at

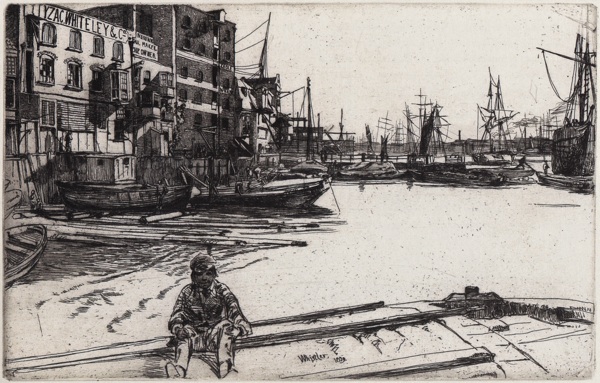

Whistler In Limehouse & Wapping

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

William Jones, Limeburner, Wapping High St

American-born artist, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, was the first artist to appreciate the utilitarian environment of the East End on its own terms, seeing the beauty in it and recognising the intimate relationship of the working people to the urban landscape they had constructed.

He was only twenty-five when he arrived in London from Paris in the summer of 1859 and, rejecting the opportunity of staying with his half-sister in Sloane St, he took up lodgings in Wapping instead. Influenced by Charles Baudelaire to pursue subjects from modern life and seek beauty among the working people of the teeming city, Whistler lived among the longshoremen, dockers, watermen and lightermen who inhabited the riverside, frequenting the pubs where they ate and drank.

The revelatory etchings that he created at this time, capturing an entire lost world of ramshackle wooden wharfs, jetties, warehouses, docks and yards. Rowing back and forth, the young artist spent weeks in August and September of 1859 upon the Thames capturing the minutiae of the riverside scene within expansive compositions, often featuring distinctive portraits of the men who worked there in the foreground.

The print of the Limeburner’s yard above frames a deep perspective looking from Wapping High St to the Thames, through a sequence of sheds and lean-tos with a light-filled yard between. A man in a cap and waistcoat with lapels stands in the pool of sunshine beside a large sieve while another figure sits in shadow beyond, outlined by the light upon the river. Such an intriguing combination of characters within an authentically-rendered dramatic environment evokes the writing of Charles Dickens, Whistler’s contemporary who shared an equal fascination with this riverside world east of the Tower.

Whistler was to make London his home, living for many years beside the Thames in Chelsea, and the river proved to be an enduring source of inspiration throughout a long career of aesthetic experimentation in painting and print-making. Yet these copper-plate etchings executed during his first months in the city remain my favourites among all his works. Each time I have returned to them over the years, they startle me with their clarity of vision, breathtaking quality of line and keen attention to modest detail.

Limehouse and The Grapes – the curved river frontage can be recognised today

The Pool of London

Eagle Wharf, Wapping

Billingsgate Market

Longshore Men

Thames Police, Wapping

Black Lion Wharf, Wapping

Looking towards Wapping from the Angel Inn, Bermondsey

You may also like to read about

Dickens in Shadwell & Limehouse

Madge Darby, Historian of Wapping