From Spitalfields to the Isle of Sheppey

Standing here among the intricate chimneypots and crenellated turrets upon the roof of Shurland Hall on the Isle of Sheppey, there are expansive views across the Thames Estuary and the North Sea in one direction and over the Isle of Harty towards the Kentish Weald in the other. Caught in a sheltered dell beneath a gentle ridge, adjoining an old duck pond and surrounded by rolling fields, it is a favoured spot for a house, and I was delighted to spend an afternoon at Shurland, courtesy of the Spitalfields Historic Buildings Trust who have spent the last five years renovating this ancient edifice.

Standing on the roof, listening to the chorus of bird song, surrounded by trees coming into leaf, and observing the towering clouds that manifest the weather for the next few hours heading towards me over the ocean, I was aware of constants that would be familiar to any of the residents over the last thousand years of habitation. A Danish Prince Hoestan built his fort on this site in 893 and King Canute resided there in 1017, with the De Shurland family arriving at the time of the Norman Conquest. Hoestan, Canute and the De Shurlands would not have seen the fields and the distant caravan park I could see, but otherwise they would recognise the view, the background sounds and aroma of pollen on the Spring breeze. When Margaret de Shurland married Sir William Cheyne in the twelfth century, the Cheyne Family became the Lords of Shurland, reaching their zenith when Henry VIII came to visit with his new wife Anne Boleyn.

Henry VIII’s visit was the occasion of the building of the wings on either side of the gatehouse that stand to this day, now the great house that once existed behind the gatehouse is long gone, evidenced only by a fragmentary ruin of a door frame that the legendary monarch entered with his ill-fated wife in 1532. It was the expense of this visit that led to the decline of the house, accelerated by the stipulation of Elizabeth I that Shurland maintain a garrison to defend the valuable trade in wool and sheepskin, from which the island takes its name. Over successive centuries, the house was let to tenant farmers, becoming a barracks in the First World War and finally derelict for much of the last century, when rumours of a ghostly lady dressed in black silk were whispered in the nearby village of Eastchurch, and barn owls took up occupation in the turrets.

As you walk uphill to approach the mellow red brick and ragstone Tudor gatehouse with its raffish towers at Shurland, there is such an undeniable grandeur that you almost expect trumpets to emerge from the turret windows to sound a fanfare. Yet once you are inside the door, you find yourself in a domestic entrance that adjusts your expectations, offering a home for your umbrella and boots, and promising a quiet cup of tea by the fire, rather than the audience with the stroppy overweight monarch, which you had feared.

The gatehouse is only one room deep and behind it is the grassy courtyard that once led to the great house. The ground levels off here, and with the rear of the gatehouse facing South, there is a milder climate, sheltered from the wind at this side. My hosts, Tim Whittaker and Oliver Leigh-Wood of the Spitalfields Trust, left me to wander around while they set to work, Oliver patching up an old wall and Tim scattering grass-seed. I discovered that the gatehouse itself offers four large austere rooms, leading off a medieval staircase enclosed in a turret – two rooms on two floors on either side, all with windows at front and back, plain stone fireplaces and tall windows.

By contrast, the East wing has been reinstated with an eighteenth century staircase salvaged from Hatton Garden, connecting more domestic-scaled bedrooms, kitchen and bathroom. This reconception of the house permits the gatehouse rooms to be used for more formal living and the other end to become the domestic hub of the household. Now that the work reaches completion and the Hall is up for sale, these spaces cry out for life, because the house is ready to become a family home again.

The Spitalfields Trust have painstakingly put the whole place back together, stabilising the structure, adding new floors, windows and roof, and using their unique collective body of experience to make sure that all aspects of the work are in harmony with the building. Even the mortar, mixed with lime and crushed seashells matches the original, reminding you in the essence of the structure, that the name Shurland derives from “Shoreland”. Everything new that you can see has been done using materials that match the originals, letting the place speak for itself – because with so much history this is a building with plenty to say.

The flat roof is a great vantage point to observe the passage of distant traffic in the estuary, it creates an attractively slow-moving focus of attention. But once the future resident has become sated with this lazy amusement, they will cast their eyes down upon the large sheltered space at the rear of the house, enclosed by a perimeter wall. The potential for a garden is god-sent. Indeed, the name of Sissinghurst has been envoked as a precedent for what could be attempted to enfold the rich palimpsest of these walls with plants and flowers. So the future owner will need green fingers, as well as a healthy bank balance.

The completion of Shurland Hall is the culmination of the most ambitious project to date for the Trust, originally formed over thirty years ago to save the old houses in Spitalfields. In this instance, they have rescued a building with a venerable history that had been reduced to a mere shell and ensured its future as a dwelling for generations to come.

If you are interested to buy Shurland Hall contact spitalfieldstrust@hotmail.com

Looking through the arched doorway that Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn walked through in 1532.

John Howard, the carpenter who has reconstructed all the woodwork at Shurland Hall.

Oliver patching up an old garden wall.

Spitalfields Antique Market 7

This charismatic chatty young Italian is Giovanni Grosso, who sells immaculately fine gloves, hand-made in the nineteen fifties by his father Alberto, the renowned glovemaker of Naples – a rare opportunity to purchase this precious stock, since Alberto ceased glovemaking in the nineteen seventies. Giovanni himself is a talented sculptor who showed me some tiny cameos he has carved with astonishing skill into seashells. Currently serving an apprenticeship in stone carving with Raniero Sambuci, Giovanni explained to me that he came to London because “…in Naples, unless you compromise with the mafioso you leave!”

This noble man with the face of saint from a Romanesque cathedral is John Andrews, who deals in “vintage fishing tackle for the soul” and is the author of “For All Those Left Behind,” a memoir about his father and fishing. Learning that angling is a dying art, I was hooked by the melancholy poetry of John’s collection which speaks of the magnificent age of British fishing between the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth century. “I am addicted to buying and selling it, and I live in my own little world,” confessed John, which sounded so attractive to me that I accepted his invitation to join a fishing trip immediately. See his collection for yourself at www.andrews of arcadia.com Trousers by Old Town.

This is the distinguished Mr Singh, expertly modelling a dress sword which belonged to the Lieutenant General to the Tower of London between 1880-90, a very fine example of its kind, that was once presented to Lord Chelmsford. “I must differentiate myself from the general public and I do it by an emphasis on quality,” explained Mr Singh modestly and, as I cast my eyes upon his impressive selection of antique silver cutlery, I found no reason to disagree. If you see Mr Singh, impeccably dressed English gentleman, and dealer in militaria and classy bric-a-brac, either here in Spitalfields or at St James, Piccadilly, be sure to pay your respects and wish him “Good day”.

This is the lovely and innately sassy Amelie Kondzot who brings a modish touch of French glamour and sophistication to the old Spitalfields Market, dealing in her select vintage French women’s fashions. “Every two months, I go back to see my family and get new stock,” she explained in her softly spoken tones – that draw you closer to catch her words – before confiding shyly, “I do have a big wardrobe of clothes, shoes and bags!”, rolling her dark eyes while blushing at her own admission. Let us indulge her penchant, because no-one can deny Amelie possesses a certain irresistible feminine chic which we need more of in Spitalfields.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

The Secrets of Christ Church, Spitalfields

There is a such a pleasing geometry to the architecture of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church, Spitalfields, completed in 1729, that when you glance upon the satisfying order of the facade you might assume that the internal structure is equally apparent – but in fact it is a labyrinth inside. Like a theatre, the building presents a harmonious picture from the centre of the stalls, yet possesses innumerable unseen passages and rooms, backstage.

When I joined the bellringers in the tower at New Year, I noticed a narrow staircase spiralled up further into the thickness of the stone spire, beyond the one I had climbed to the bellringers’ loft. Since then I have harboured a burning curiousity to ascend those steps, and yesterday I returned to climb that mysterious staircase to discover what is at the top. As you ascend the worn stone steps within the thickness of the wall, the walls get blacker and the stairs get narrower and the ceiling gets lower. By the time you reach the top, you are stooping as you climb and the giddiness of walking in circles permits the illusion that, as much as you are ascending into the sky, you might equally be descending into the earth. There is a sense that you are beyond the compass of your experience, entering indeterminate space.

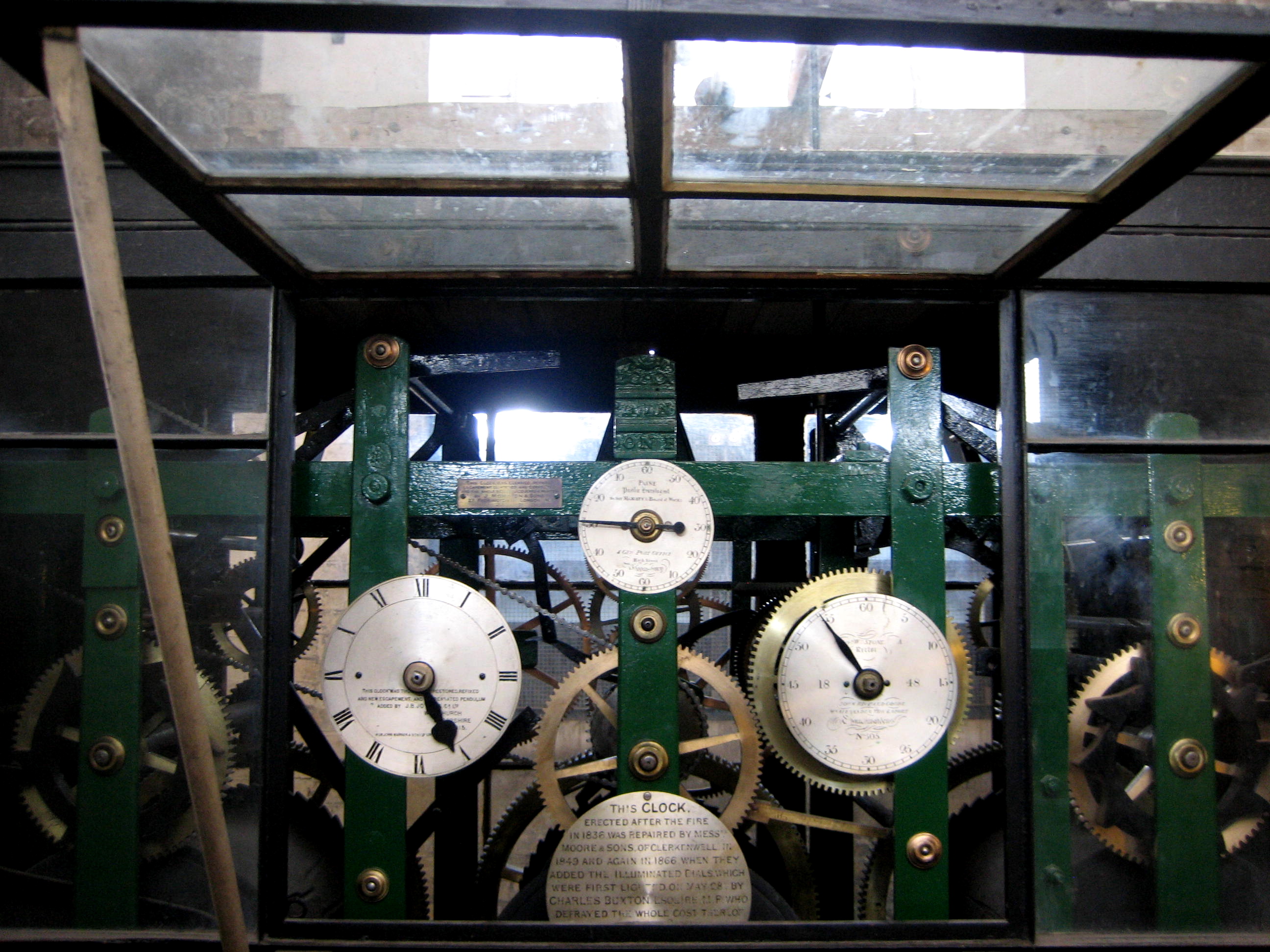

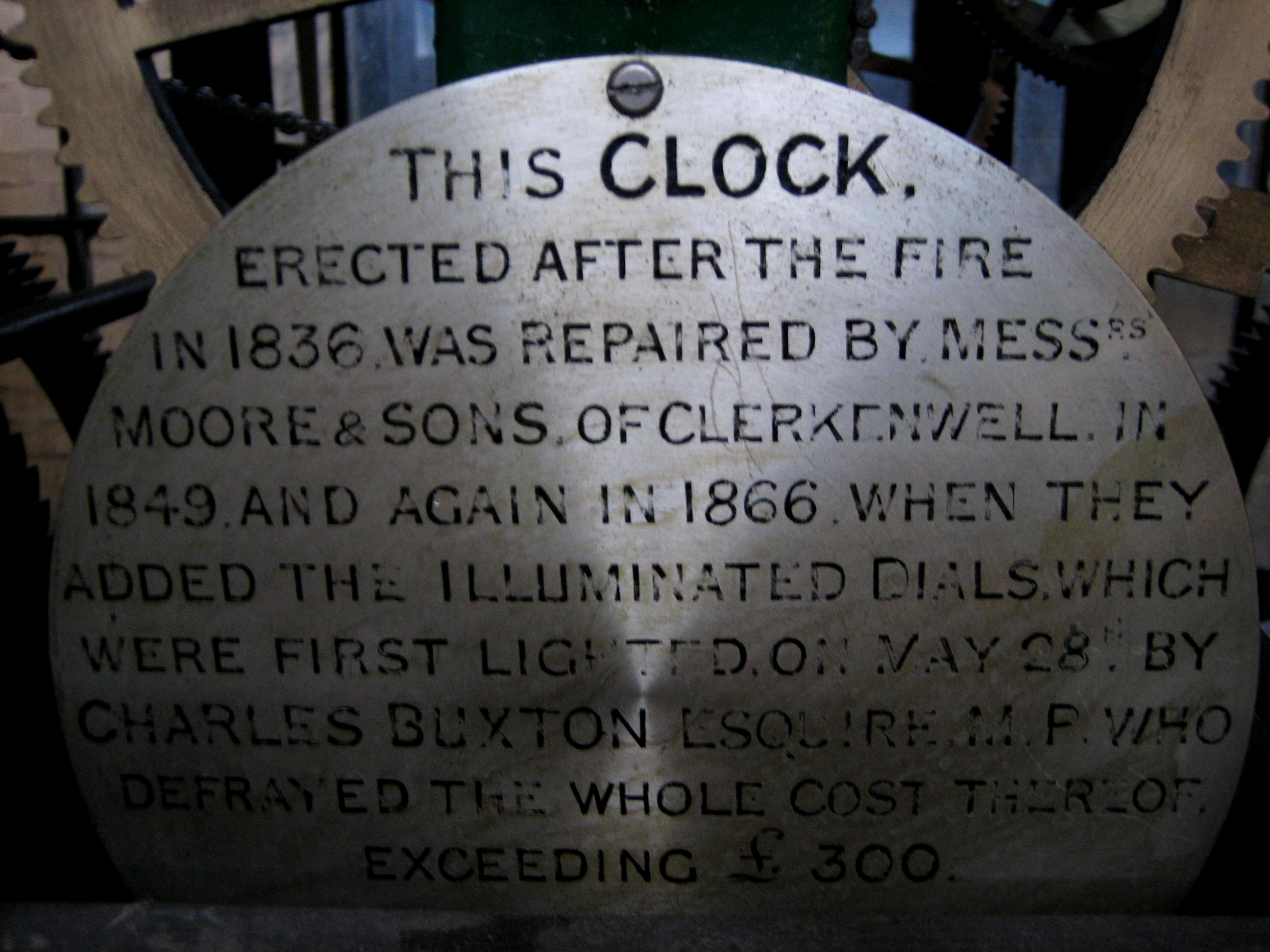

No-one has much cause to come up here and, when we reached the door at the top of the stairs, Iesah Littledale, the head verger, was unsure of his keys. As I recovered my breath from the climb, while Iesah tried each key in turn upon the ring until he was successful, I listened to the dignified tick coming from the other side of the door. When Iesah opened the door, I discovered it was the sound of the lonely clock that has measured out time in Spitalfields since 1836 from the square room with an octagonal roof beneath the pinnacle of the spire. Lit only by diffuse daylight from the four clock faces, the renovations that have brightened up the rest of the church do not register here. Once we were inside, Iesah opened the glazed case containing the gleaming brass wheels of the mechanism, turning with inscrutable purpose within their green-painted steel cage, driving another mechanism in a box up above that rotates the axles, turning the hands upon each of the clock faces. Not a place for human occupation, it was a room dedicated to time and, as intervention is required only rarely here, we left the clock to run its course in splendid indifference.

By contrast, a walk along the ridge of the roof of Christ Church, Spitalfields, presented a chaotic and exhilarating symphony of sensations, buffered by gusts of wind beneath a fast-moving sky that delivered effects of light changing every moment. It was like walking in the sky. On the one hand, Fashion St and on the other Fournier St, where the roofs of the early eighteenth century Huguenot houses topped off with weavers’ lofts created an extravagant roofscape of old tiles and chimney pots at odd angles. Liberated by the experience, I waved across the chasm of the street to residents of Fournier St in their rooftop gardens opposite, like one waving to people from a train.

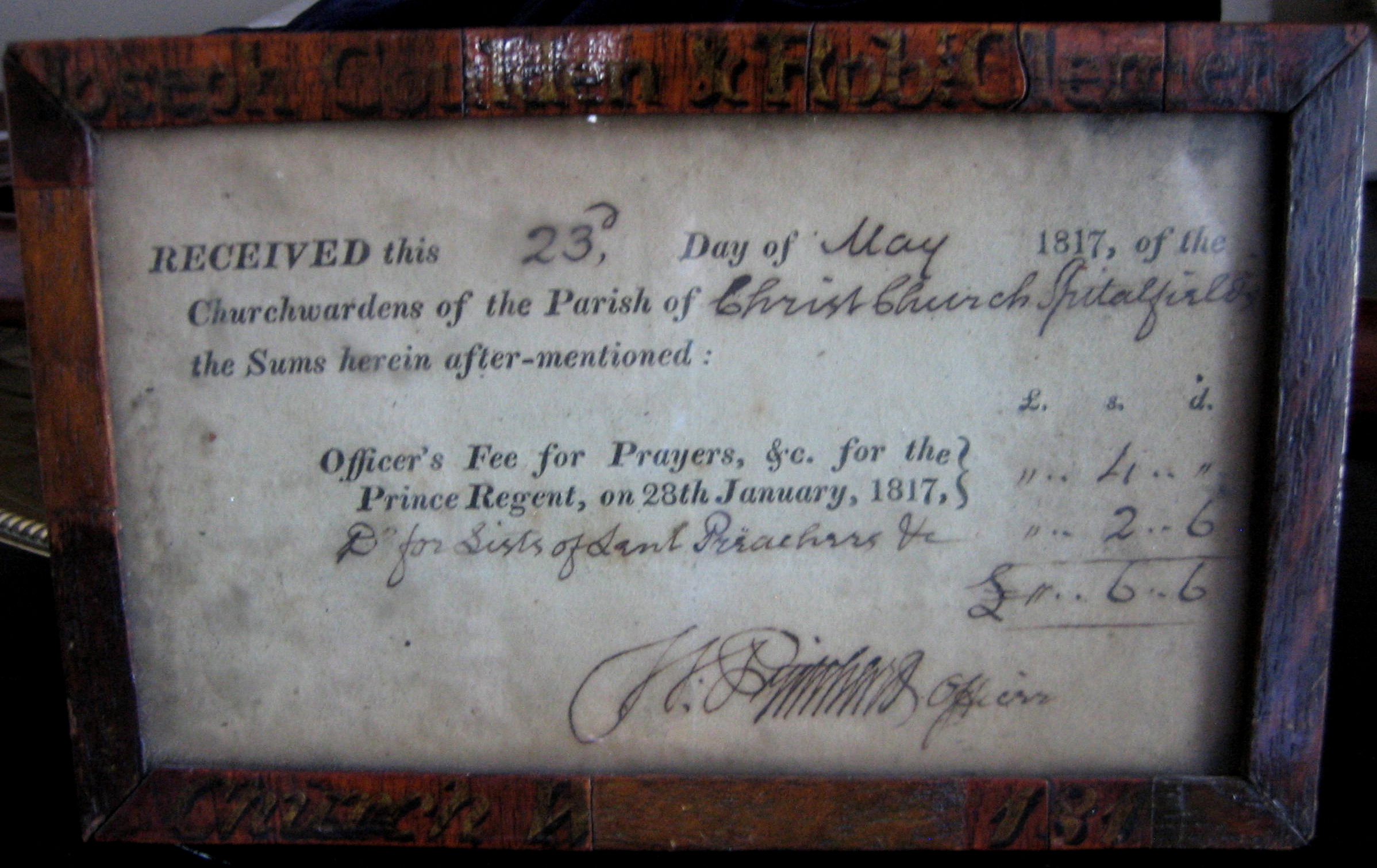

Returning to the body of the church, we explored a suite of hidden vestry rooms behind the altar, magnificently proportioned apartments to encourage lofty thoughts, with views into the well-kept rectory garden. From here, we descended into the crypt constructed of brick vaults to enter the cavernous spaces that until recent years were stacked with human remains. Today these are large, apparently innocent limewashed spaces without any tangible presence to recall the thousands who were laid to rest here until it was packed to capacity and closed for burial in 1812 by Rev William Stond MA, as confirmed by a finely lettered stone plaque.

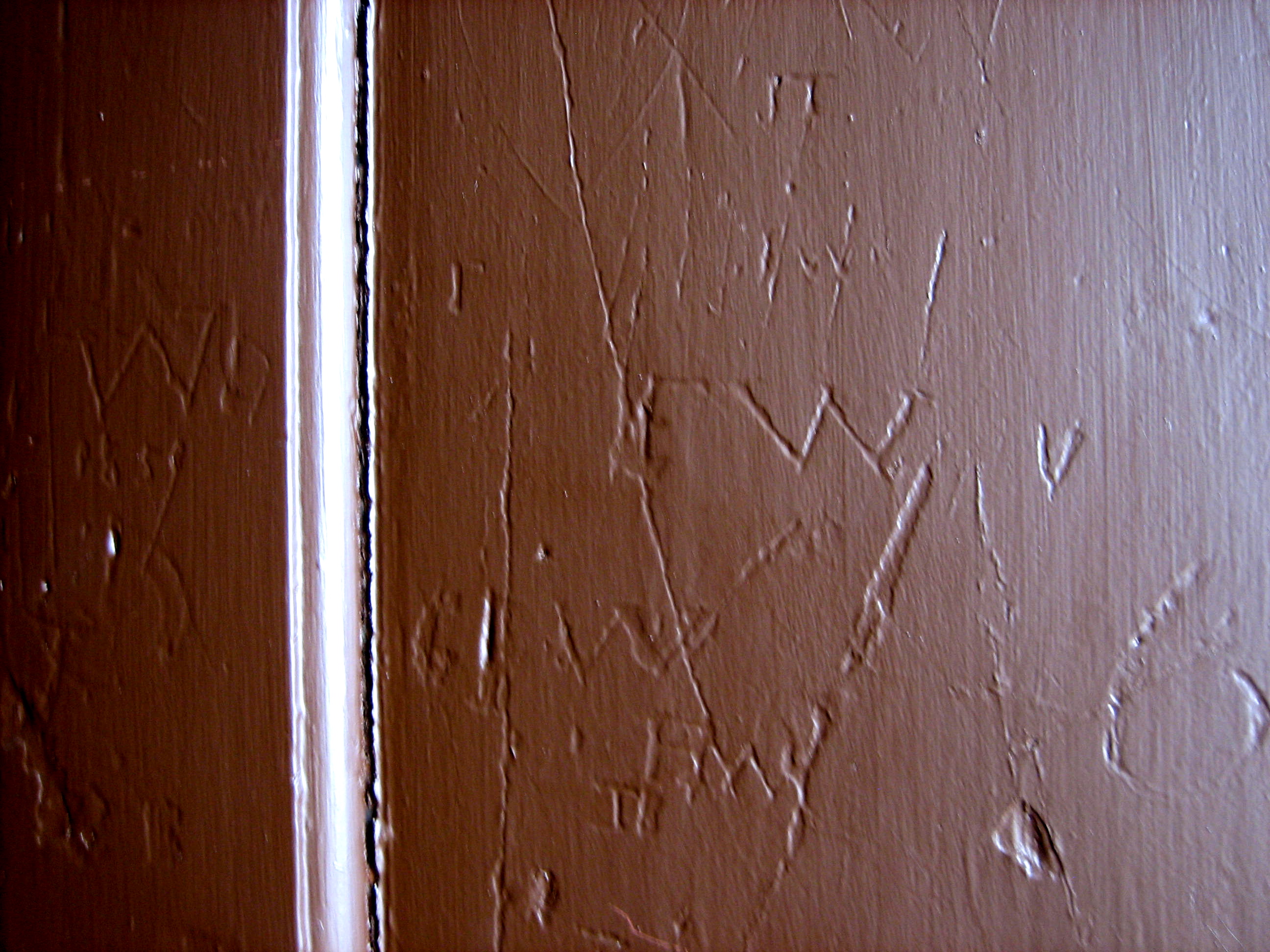

Passing through the building, up staircases, through passages and in each of the different spaces from top to bottom, there were so many of these plaques of different designs in wood and stone, recording those were buried here, those who were priests, vergers, benefactors, builders and those who rang the bells. In parallel with these demonstrative memorials, I noticed marks in hidden corners, modest handwritten initials, dates and scrawls, many too worn or indistinct to decipher. Everywhere I walked, so many people had been there before me, and the crypt and vaults were where they ended up.

My visit started at the top and I descended through the structure until I came, at the end of the afternoon, to the small private vaults constructed in two storeys beneath the porch, where my journey ended, as it did in a larger sense for the original occupants. These delicate brick vaults, barely three feet high and arranged in a crisscross design, were the private vaults of those who sought consolation in keeping the family together even after death. All cleaned out now, with modern cables and pipes running through, I crawled into the maze of tunnels and ran my hand upon the vault just above my head. This was the grave where no daylight or sunshine entered, and it was not a place to linger on a bright afternoon in May.

Christ Church gave me a journey through many emotions, and it fascinates me that this architecture can produce so many diverse spaces within one building and that these spaces can each reflect such varied aspects of the human experience, all within a classical structure that delights the senses through the harmonious unity of its form.

The mechanism of this clock runs so efficiently that it only has to be wound a couple of times each year.

Looking up into the spire.

A model of the rectory in Fournier St.

On the reverse of the door of the organ cupboard.

In the vestry.

Beneath the porch,two storeys of vaults descend into the earth.

For nearly three centuries, the shadow of the spire has travelled the length of Fournier St each afternoon.

The ‘Drawing London’ Group in Spitalfields

One afternoon last Winter, as I was walking through the lobby of the Barbican library to return my books, a beautiful drawing caught my eye among the works exhibited there. It was a fine architectural drawing, with precise spidery lines and subtle watercolour tints, by the wonderfully named Shelby Dawbarn and the exhibition was organised by the ‘Drawing London’ Group.

I wrote a compliment in their comments book and, to my surprise, within days I received an invitation to the opening party where I had the honour of meeting the talented Shelby Dawbarn. She explained that, although she had once studied architecture and attended Liverpool College of Art, her talent in drawing had only come to fruition recently, after a long gap in which she had a family and a career. It was inspiring to meet someone who had recently achieved the fulfilment of a gift that had lain dormant for years – discovering so much pleasure in drawing today.

Each month, the ‘Drawing London’ Group, which has around fifteen members, meets in a different part of the city and spends a day drawing on the streets. Once I was introduced to Bill Aldridge and Marion Wilcocks who (with Shelby) founded the group spontaneously in 2003 when they met on a course at the Prince’s Drawing School, I took the opportunity to invite them over to Spitalfields and last week it was my pleasure to welcome them to the neighbourhood.

When I arrived in the morning to greet them at St John, Nicky Sherrott was already hungrily tucking in to a bacon sandwich as sustenance for a serious day’s drawing and I was captivated at once by the group’s collective anticipation at the potential which lay ahead. Even though these were Londoners and it was merely one day’s drawing, there was the feeling of an expedition. On these occasions, the members of this gentle and freewheeling drawing group leave their usual lives at home and set out, enjoying the camaraderie of the freshly sharpened pencil, to look at life afresh. It is a small adventure and an intensely civilised one. Last Friday, clutching their fishing stools and drawing boards, they spread out around the Spitalfields Market and the surrounding streets, and set to work.

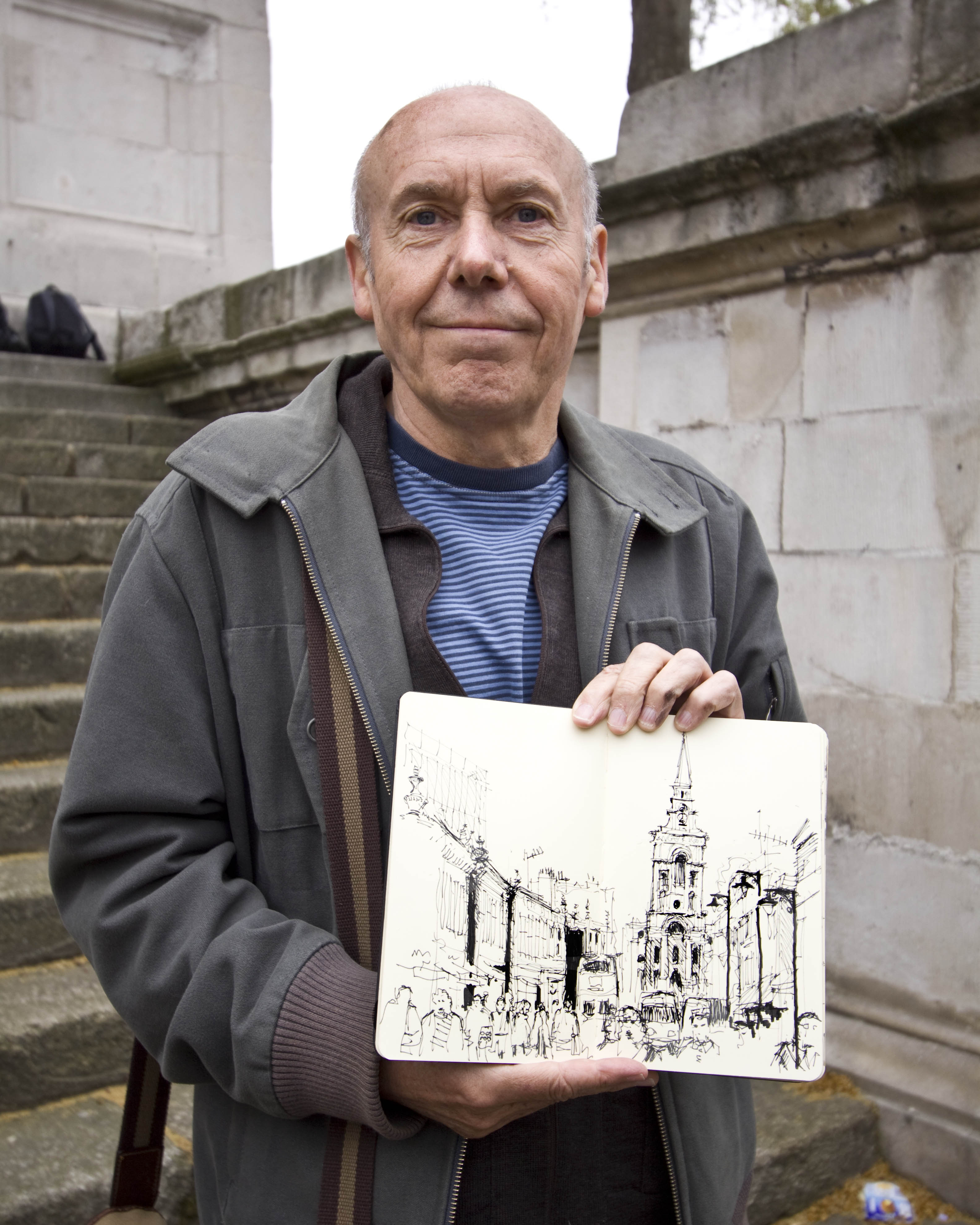

When I returned later, the members were all shyly clutching their artworks, but I managed to persuade them to step out from the lunch queue and onto the steps of Christ Church, where Spitalfields Life contributing photographer Jeremy Freedman took their portraits with their drawings, which you can see below.

Holding up her sketchbook in the wind with her curls blowing everywhere, the charming Wendy Winfield was especially pleased to be back in Spitalfields, and fascinated by all the changes, because she first came here while she was at art school in London between 1947-53, when this was the Jewish neighbourhood. “In those days, you left home to go to art school at sixteen,” she confided, “it was very exciting!” Such was her passionate curiousity that Jeremy offered to take Wendy inside the Sandys Row Synagogue, one of the last fragments of Jewish Spitalfields.

“I love London, my mother was a Londoner. She thought London was the only place in the world and she instilled it in me. So I am grateful for the chance to travel round London and see the parts other people don’t know,” explained Marilyn Southey modestly, a woman of natural elegance who had passed her morning drawing in the market, discovering a consensus from the other members that the elaborate cast iron roof makes it a challenging subject. Meanwhile, Nicky Sherrott, the keen-eyed retired lawyer who enjoys bacon sandwiches, confessed to me that after twenty years working in the city, she appreciated the opportunity drawing gave simply to look at things closely. For her, the finished artwork was secondary to the privilege of concentrated looking.

After lunch, I accompanied the group on the private tour of the Sandys Row Synagogue hosted by Jeremy, and it was refreshing to find myself amongst people for whom, although they had all lived plenty of life, the common factor was that they retained their sense of wonder. I could have spent the whole afternoon talking with these folk, but before long it was time for them to return to their drawings and make the most of the rest of their day in Spitalfields.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Joan Naylor of Bellevue Place

This is Joan Naylor, photographed last year in the garden of her house in Bellevue Place, the hidden terrace of nineteenth century cottages in Stepney featured in “The London Nobody Knows,” that I visited recently in the footsteps of Geoffrey Fletcher.

Joan moved into Bellevue Place with her husband Bill in 1956 when they were first married, and they brought up their family there. “When we first moved in it was known as ‘Bunghole Alley’ and no-one wanted to live there,” she recalled with a shrug. Originally built as a crescent of cottages around a green which served in the Victorian period as tea gardens, Charringtons built a brewery on the site, lopping the terrace in half, constructing a wall round it and using the cottages for their key workers. Enclosed on all sides, there is a door in one wall that led directly into the brewery, which remains locked today, now the brewery is gone.

Joan’s husband, Bill, was a load clerk whose job it was to devise the most efficient delivery routes and loads for the draymen on the rounds of all the Charringtons pubs in the East End. When Joan arrived, the brewery workers started early, commencing each day with a few pints in the tap-room before beginning work, and Bill was able to pop home through the door in the wall at nine o’clock to enjoy breakfast with Joan.

“If you looked out of the bedroom window, you could see a pile of wooden barrels a hundred foot high, and the smell of stale beer permeated the air.” said Joan, recalling her first impressions.“Nothing had been changed in the house. The brewery brought in the decorators but we still had a tiny bathroom off the kitchen and an outside loo. It didn’t bother me. When you think we brought up six of us in that house – I remember the ice on the inside of the window! We used to cut up old barrels to light the fire and they’d burn really well because they had pitch in them.”

It is with pure joy that Joan remembers the days when there were around a dozen children, including her own, living in Bellevue Place. They all played together, chasing up and down the gardens, an ideal environment for games of hide and seek, and there were frequent parties when everyone celebrated together on birthdays, Christmas and bonfire night. “There was always a party coming up, always something to look forward to,” explained Joan, because it was not only the children who enjoyed a high old time in the secret enclave of Bellevue Place.

Although unassuming by nature, Joan became enraptured with delight as she explained that, since everyone knew each other on account of working together at the brewery, there was a constant round of parties for adults too. It was the arrival of Stan, the refrigeration engineer and famous practical joker, to live in the end cottage, that Joan ascribes as the catalyst for the Golden Age of parties in Bellevue Place. You can see Stan in the pith helmet in the photo below. When all the children were safely tucked up asleep (“We had children, we couldn’t go out“), the residents of Bellevue Place enjoyed lively fancy dress parties, in and out of the gardens, and each other’s houses too. “The word would go around from Stan and we would go round the charity shops to see what we could find, but no-one would tell anyone what their outfit was going to be. It was lovely. Everybody had fun and nobody carried on with each other’s wives.” Joan told me.

Let us not discount the proximity of the brewery in our estimation of the party years at Bellevue Place because I have no doubt there was never any shortage of drinks. Also, number one Bellevue Place, the large house at the beginning of the terrace, was empty and disused for many years, and the brewery even gave the residents a key, so it could become the social venue and youth club for the terrace, with a snooker table, and a roof top that was ideal for firework parties. With all these elements at their disposal, the enterprising party animals of Bellevue Place became expert at making their own entertainments.

There is a bizarre twist to Joan’s account of the legendary parties at Bellevue Place, because she was born on the twenty-ninth of February, which means she only had a birthday every leap year. So, when she did have a birthday, Joan’s neighbours organised parties appropriate to the birthday in question. In the photo below you can see her reading a Yogi Bear annual as a present for her seventh birthday, when she was twenty-eight years old. I hope Joan will not consider it indiscreet if I reveal to you that she has now at last reached her twenty-first birthday.

It is apparent that the mutual support Joan enjoyed amongst the women in her terrace, who became her close friends, and the camaraderie shared by the men, who worked together in the brewery – all surrounded by the host of children that played together – created an exceptionally warm and close-knit community in Bellevue Place, that became in effect an extended family. Even though they did not have much money and lived together in a house that many would consider small for six, Joan’s memories of her own family life are framed by this rare experience of the place and its people in this particular circumstance, and it is an experience that many would envy.

Last winter, Joan moved out of Bellevue Place for good, but she had become the resident who had lived there the longest and remains the living repository of its history. Last week, I visited her in sheltered housing in Bethnal Green where she told me her beautiful stories of the vibrant social life of this modest brewery terrace, while her son John, who is a regular visitor, worked on his handheld computer in the corner of the room.

“We were very lucky to have lived down there to bring up the family,” said Joan, her eyes glistening with happiness, as she spread out her collection of affectionate and playful photographs, cherishing the events which incarnate the highlights of her existence in Bellevue Place. She may have first known it as “Bunghole Alley,” but for Joan Naylor “Bellevue Place” lived up to the promise of its name.

Joan, as flapper, with her neighbour Harry.

Joan (holding the glass) and her neighbours as hippies.

Lil, Teddy and Tilly, Joan’s neighbours in Bellevue Place.

Lil, Teddy and Tilly, Joan’s neighbours in Bellevue Place.

Joan with her husband Bill, and Mrs Boxall who had lived the longest in Bellevue Place at that time.

Joan with her husband Bill, and Mrs Boxall who had lived the longest in Bellevue Place at that time.

One of Joan’s birthday parties, with presents appropriate to her seventh birthday.

One of Joan’s birthday parties, with presents appropriate to her seventh birthday.

Joan Naylor

Columbia Road Market 33

The first weekend in May traditionally produces the most profitable Sunday’s trading in the entire year for the plant sellers of Columbia Rd. In spite of this morning’s cheery shouts – from the trader wishfully singing,“Rain before seven, dry before eleven,” – it was obvious they were all dismayed by the downpour that drove their customers away. I was there early among the hardy souls that could not keep away and our fortitude was rewarded by the astounding display of plants just waiting to be carried off the to fill the gardens of East London.

Incongruously, I was searching for some flowers to enhance a dry border against a sunny wall in my garden and I found these three plants which complement each other beautifully. The white flower is a hardy alpine variety of Phlox that grows low to ground and cost me £4. It has the softest grey-green leaves and the sharp white flowers have tiny purple rosettes at the heart. The blue flower is Lithodora, another hardy alpine variety with gentian-like flowers in finely differentiated tones of blue, for £5. These are both contrasted nicely with this tricolore Sage for £3, one of my favourite herbs, to be savoured for its subtly variegated red, green and white leaves as well as its culinary potential.

Pearl Binder, artist & writer

“City and East End meet here, and between five and six o’clock it is a tempest of people.”

This is Aldgate, pictured in a lithograph of 1932 by Pearl Binder, as one of a series that she drew to illustrate “The Real East End” by Thomas Burke, a popular writer who ran a pub in Poplar at the time. Among the many details of this rainy East End night that she evokes so atmospherically with such economy of means, I could not help noticing the number fifteen bus which still runs through Aldgate today. In her lithographs, Pearl Binder found her ideal medium to portray London in the days when it was a grimy city, permanently overcast with smoke and smog, and her eloquent visual observations were based upon first hand experience.

This book was brought to my attention by Pearl Binder’s son Dan Jones, the rhyme collector, who explained that his mother came from Salford to study at the Central School of Art and lived in Spread Eagle Yard, Whitechapel in the nineteen twenties and thirties. It was an especially creative period in her life and an exciting time to be in London, when one of as the first generation after the First World War, she took the opportunity of the new freedoms that were available to her sex.

In Thomas Burke’s description, Pearl Binder’s corner of Whitechapel sounds unrecognisably exotic today, “It is in one of the old Yards that Pearl Binder has made her home, and she has chosen well. She enjoys a rural atmosphere in the centre of the town. Her cottage windows face directly onto a barn filled with hay-wains and fragrant with hay, and a stable, complete with clock and weather-vane; and they give a view of metropolitan Whitechapel. One realises here how small London is, how close it still is to the fields and farms of Essex and Cambridgeshire.” From Spread Eagle Yard, Pearl Binder set out to explore the East End, and these modest black and white images illustrate the life of its people as she found it.

Her best friend was Aniuta Barr (known to Dan as Aunt Nuta), a Russian interpreter, who remembered Lenin, Kalinin and Trotsky coming to tea at their family home in Aldgate when she was a child. Dan described Aunt Nuta announcing proudly, “Treat this bottom with respect, this has sat upon the knee of father Lenin!” He called her his fairy godmother, because she did not believe in god and at his christening when the priest said, “In the name of the father, the son and the holy ghost…”, she added, “…and Lenin”.

Pearl Binder’s origins were on the border of Russia and the Ukraine in the town of Swonim, which her father Jacob Binderevski, who kept Eider ducks there, left to come to Britain in 1890 with a sack of feathers over his shoulder. After fighting bravely in the Boer War, he received a letter of congratulation from Churchill inviting him to become English. Pearl lived until 1990 and Nuta until 2003, both travelling to Russia and participating in cultural exchange between the two countries through all the ups and downs, living long enough to see the Soviet Union from beginning to end in their lifetimes.

Pearl left the East End when she married Dan’s father Elwyn Jones, a young lawyer (later Lord Elwyn Jones and member of parliament for Poplar), and when they were first wed they lived at 1 Pump Court, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, yet she always maintained her connections with this part of London. “Mum was trying to fry an egg and dad came to rescue her,” was how Dan fondly described his parents’ meeting, adding,“I think the egg left the pan in the process,” and revealing that his mother never learnt to cook. Instead he has memories of her writing and painting, while surrounded by her young children Dan, Josephine and Lou. “She was amazingly energetic,” recalled Dan,“Writing articles for Lilliput about the difficulties of writing while we were crawling all over the place.”

Pearl Binder’s achievements were manifold. In the pursuit of her enormous range of interests, her output as a writer and illustrator was phenomenal – fiction as well as journalism – including a remarkable book of pen portraits “Odd Jobs” (that included a West End prostitute and an East End ostler), and picture books with Alan Lomax and A.L.Lloyd, the folk song collectors. In 1937, she was involved in children’s programmes in the very earliest days of television broadcasting. She was fascinated by Pocahontas, designing a musical on the subject for Joan Littlewood at the Theatre Royal Stratford East. She was an adventurous traveller, travelling and writing about China in particular. She was an advocate of the pearly kings & queens, designing a pearly mug for Wedgwood, and an accomplished sculptor and stained glass artist, who created a series of windows for the House of Lords. The explosion of creative energy that characterised London in the nineteen twenties carried Pearl Binder through her whole life.

“She was always very busy with all her projects, some of which came about and some of which didn’t.” said Dan quietly, as we leafed through a portfolio, admiring paintings and drawings from his mother’s long career. Then as he closed the portfolio and stacked up all her books and pictures that he had brought out to show me – just a fraction of all of those his mother created – I opened the copy of “The Real East End” to look at the pictures you can see below and Dan summed it up for me. “I think it was a very important part of her life, her time in the East End. She was really looking at things and using her own eyes and getting a feel of the place and the people – and I think the best work of her life was done during those years.”

A Jewish restaurant in Brick Lane.

A Jewish restaurant in Brick Lane.

A beigel seller in Whitechapel High St.

A beigel seller in Whitechapel High St.

A Jewish bookshop in Wentworth St.

A slop shop in the East India Dock Rd. Pearl Binder’s self-portrait

Pearl Binder’s self-portrait

Pearl Binder ( 1904-1990)