Beating the Bounds in the City of London

Yesterday, I joined my old friends from the Lord Mayor’s Parade, the Portsoken Militia, along with a host of City worthies and the children of Sir John Cass Primary School at the annual Beating of the Bounds ceremony, setting out from St Botolph-without-Aldgate to walk the boundaries of the Portsoken ward in the City of London. As we set forth with the Ward Constable in front, followed by the Beadle leading the Potsoken Millitia and the Aldermen of Portsoken, ahead of the mass of schoolchildren straggling along at the rear, we made an unlikely procession, but one impressive enough to stop the traffic, cause every office worker to reach for their camera phone and generally bring the City to a halt around us.

First stop was Mitre Square, where a bunch of tourists on a Jack the Ripper tour had the shock of their lives as we all came round the corner, walking out of history with a mob of children in tow. “Get your cameras ready!” quipped the Ward Constable, with a smirk of pride, occasioning a dramatic moment seized by Laura Burgess, the Rector of St Botolph, to announce the first stop on our circuit, causing everyone to gather round in a crowd.

There is a curious mixture of civility and anarchy about the Beating the Bounds ceremony, held annually on Ascension Day, which the Rector explained dates from a time when maps were rare and the community joined together to mark the boundaries of the parish, and to pray for God’s blessing to ward off evil from the territory. Civility is represented by the dignitaries and anarchy is introduced when the children are handed sticks and given liberty to use them. Although, in the absence of boundary stones, lampposts, bollards, signs, railings and a wall had to stand substitute, none of the children seemed disappointed. Without hesitation, they all embraced the absurdity of this extraordinary moment, in which the adults distributed long sticks and stood around in approval, as the children worked themselves up into a state of great excitement, battering the designated inert objects with gleeful enthusiasm. In fact, I can confirm a proud consensus held by the adults present that the children all played their part well.

Naturally, there is a certain necessary ritual that precedes this invitation to violence. In each location, as a precursor, the Rector delivered a brief history lecture followed by a quiet prayer. Then the Alderman gave the instruction, “Now let us beat this boundary!” and everyone chanted “Cursed be he that removeth his neighbours’ landmark.” while wielding their sticks, and the children cried, “Beat! Beat! Beat!”

We moved on swiftly through Devonshire Place, Petticoat Lane, across Aldgate High St, down to Portsoken St, St Clare St and back up the Minories to St Botolph’s Church in an hour’s circuit, stopping off for the ritual beatings as went. As the journey progressed, the various constituencies in our procession mingled, acknowledging that we were fellow travellers upon some kind of pilgrimage with our particular chosen purpose, that set us apart from the present day world around us. During the Rector’s history lectures we all nodded in reverence to the waves of immigrants in Petticoat Lane, the memory of Wat Tyler and the Peasants’ Revolt, in whose footsteps we trod when in Aldgate High St, and William the Conquerer, who entered the City through Portsoken St and is known to this day here as William I, because he negotiated a truce with the City of London, he did not conquer it.

Arriving back at St Botolph, the children were invited to beat upon the churchyard railings one last time, and then the sticks were summarily removed from their sweaty hands and locked away in a vestry cupboard until next year, before the possibility of any improvised high jinks could occur.

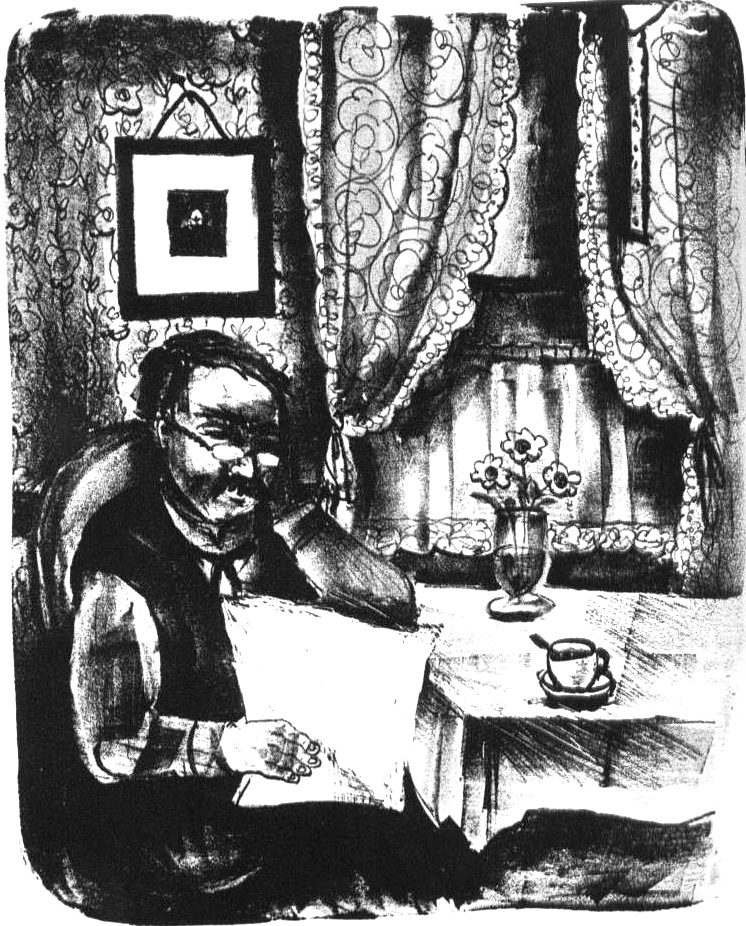

When the children went home, the adults, who were now feeling rather playful – catching the infectious holiday spirit engendered by all the excited children – had their pictures taken on the steps of St Botolph. This was followed by tea and iced cakes inside and, for the duration of the party, the atmosphere was of a parish tea in a small village. The bounds had been truly beaten for another year. We were celebrating. We all felt we have achieved something, although no-one quite knew what. Children and adults together, we had left our daily routines for an hour and shared our delight in the romance of the great city, enacting a ritual that drew us closer to each other and to all those who went before.

Brian Buckington, the Commanding Office of the Portsoken Militia, enjoys a well deserved cup of tea, served by the ladies at St Botolph without Aldgate, after leading his troops around the City of London.

Spitalfields Antiques Market 8

This is Harvey Derriell, a lean and soulful Frenchman of discriminating tastes, and a connoisseur of tribal art from West Africa, with his prized collection of sculptures, textiles and beads, including my own personal favourite, chevron trading beads. “Fourteen years ago, I went to Mali, and I fell in love with the place and the people and I wanted to return. Now I go back four times a year.” revealed Harvey, brimming with delight. I was dismayed to learn that the Golonina bead market is closed but Harvey reassured me that beads are still to be found. “In Bamako, they ask ‘What do you want? Drugs, gold, diamonds, girls, boys or beads?’ “ he explained.

This is Anna Karlin who is moving to New York and selling off all her things before she departs these shores permanently. “I still have a house full!” she admitted with a cheerful shrug, carefree yet shivering in the May sunshine, as she pulled the blanket round her, in unconscious evocation of the woman in Ford Madox Brown’s painting of nineteenth century emigrants The Last of England. Anna is a designer who is moving from Hackney to Manhattan’s fashionable Lower East Side, so once she has disposed of her things here, she can go to the Chelsea Flea Market each Sunday in the West Village and start all over again.

This dignified fellow is Alex McHattie, a book dealer, who has been trading in markets on and off since 1978. “I’ve had jobs in between but I always come back to having a stall,” he confided to me with a gentle smile, acknowledging the intangible magnetism of the market place that everyone here recognises. A quietly cultured man, I have no doubt Alex has read every volume in his fascinatingly varied stock, which he characterised tersely as, “Mainly arts books, illustrated literature, and a few pieces of junk.” – revealing that Alex has mastered both the appealingly droll understatement and the cool learned aura, which distinguish nobility among the second-hand book dealers of London.

This is Elizabeth Bartley who deals in jewellery and old tins.“It’s a good thing to buy things you like and hold onto them for a while before passing them on,” explained this generous-spirited Australian woman, who teaches children with special needs for three days every week. Holding up a sparkly nineteenth century ring with stones in the shape of a heart, she used this to illustrate “the sentiment that is attached to things,” which touches her. Every single thing on Elizabeth’s stall has particular meaning for her personally, especially the commemorative biscuit tins that people treasured once, yet have become disposable items today.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Syd's Coffee Stall, Shoreditch High Street

This is Sydney Edward Tothill pictured in 1920, proprietor of the Coffee Stall that still operates, open for business five days a week at the corner of Calvert Avenue and Shoreditch High St, where this photo survives, screwed to the counter of the East End landmark that carries his name. “Ev’rybody knows Syd’s. Git a bus dahn Shoreditch Church and you can’t miss it. Sticks aht like a sixpence in a sweep’s ear,” reported the Evening Telegraph in 1959.

This is a story that began in the trenches of World War I when Syd was gassed. On his return to civilian life in 1919, Syd used his invalidity pension to pay £117 for the construction of a top quality mahogany tea stall with fine etched glass and gleaming brass fittings. And the rest is history, because it was of such sturdy manufacture that it remains in service over ninety years later.

Jane Tothill, Syd’s granddaughter who upholds the proud family tradition today, told me that Syd’s Coffee Stall was the first to have mains electricity, when in 1922 it was hooked up to the adjoining lamppost. Even though the lamppost in question has been supplanted by a modern replacement, it still stands beside the stall to provide the power supply. Similarly, as the century progressed, mains water replaced the old churn that once stood at the rear of the stall and mains gas replaced the brazier of coals. In the nineteen sixties, when Calvert Avenue was resurfaced, Syd’s stall could not be moved on account of his mains connections and so kerbstones were placed around it instead. As a consequence, if you look underneath the stall today, the cobbles are still there.

Throughout the nineteenth century, there was a widespread culture of Coffee Stalls in London, but, in spite of the name – which was considered a classy description for a barrow serving refreshments – they mostly sold tea and cocoa, and in Syd’s case “Bovex”, the “poor man’s Bovril.” The most popular snack was Saveloy, a sausage supplied by Wilsons’ the German butchers in Hoxton, as promoted by the widespread exhortation to “A Sav and a Slice at Syd’s.” Even Prince Edward stopped by for a cup of tea from Syd’s while on his frequent nocturnal escapades in the East End.

With his wife May, Syd ran an empire of seven coffee stalls and two cafes in Rivington St and Worship St. The apogee of this early period of the history of Syd’s Coffee Stall arrived when it featured in a silent film Ebb Tide, shot in 1931, starring the glamorous Chili Bouchier and praised for its realistic portrayal of life in East London. The stall was transported to Elstree for the filming, the only time it has ever moved from its site. While Chili acted up a storm in the foreground, as a fallen woman in tormented emotion upon the floor, you can just see Syd discharging his cameo as the proprietor of an East End Coffee Stall with impressive authenticity, in the background of the still photograph below.

In spite of Syd’s success, Jane revealed that her grandfather was “a bit of a drinker and gambler” who gambled away both his cafes and all his stalls, except the one at the corner of Calvert Avenue. When Syd junior, Jane’s father was born, finances were rocky, and he recalled moving from a big house in Palmer’s Green to a room over a laundry, the very next week. May carried Syd junior while she was serving at the stall and it was pre-ordained that he would continue the family business, which he joined in 1935.

In World War II, Syd’s Coffee Stall served the ambulance and fire services during the London blitz. Syd and May never closed, they simply ran to take shelter in the vaults of Barclays Bank next door whenever the air raid sounded. When a flying bomb detonated in Calvert Avenue, Syd’s stall might have been destroyed, if a couple of buses had not been parked beside it, fortuitously sheltering the stall from the explosion. In the blast, poor May was injured by shrapnel and Syd suffered a mental breakdown, leaving their young daughter Peggy struggling to keep the stall open.

The resultant crisis at Syd’s Coffee Stall was of such magnitude that the Mayor of Shoreditch and other leading dignitaries appealed to the War Office to have Syd junior brought home from a secret mission he was undertaking for the RAF in the Middle East, in order to run the stall for the ARP wardens. It was a remarkable moment that revealed the essential nature of the service provided by Syd’s Coffee Stall to the war effort on the home front in East London, and I can only admire the Mayor’s clear-sighted sense of priority in using his authority to demand the return of Syd from a secret mission because he was required to serve tea in Shoreditch. As he wrote to May in January 1945, “I do sincerely hope that you are recovering from your injuries and that your son will remain with you for a long time.”

Syd junior was determined to show he was more responsible than his father and, after the war, he bravely expanded the business into catering weddings and events along with this wife Iris, adopting the name “Hillary Caterers” as a patriotic tribute to Sir Edmund Hillary who scaled Everest at the time of the coronation of Elizabeth II. No doubt you will agree that as a caterer for a weddings, “Hillary Caterers” sounds preferable to “Syd’s Coffee Stall.” In fact, Syd junior’s ambition led him to become the youngest ever president of the Hotel & Caterer’s Federation and the only caterer ever to cater on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral, topping it off by becoming a Freeman of the City of London.

Jane Tothill began working at the stall in 1987 with her brothers Stephen and Edward, and the redoubtable Clarrie who came for a week “to see if she liked it” and stayed thirty -two years. Jane manages the stall today with the loyal assistance of Francis, who has been serving behind the counter these last fifteen years. Nowadays the challenges are parking restrictions that make it problematic for customers to stop, hit and run drivers who frequently cause damage which requires costly repair to the mahogany structure and graffiti artists whose tags have to be constantly erased from the venerable stall. Yet after ninety years and three generations of Tothills, during which Syd’s Coffee Stall has survived against the odds to serve the working people of Shoreditch without interruption, it has become a symbol of the enduring human spirit of the populace here.

Syd’s Coffee Stall is a piece of our social history that does not draw attention to itself, yet deserves to be celebrated. Syd senior might not have survived the trenches in 1919, or he might have gambled away this stall as he did the others, or the bomb might have fallen differently in 1944. Any number of permutations of fate could have led to Syd’s Coffee Stall not being here today. Yet by a miracle of fortune, and thanks to the hard work of the Tothill family we can enjoy London’s oldest Coffee Stall here in our neighbourhood. We must cherish it now, because the story of Syd’s Coffee Stall teaches us that there is a point at which serving a humble cup of tea transcends catering and approaches heroism.

May Tothill, Syd’s wife, behind the counter in the nineteen thirties.

Jane Tothill, Syd and May’s granddaughter, behind the counter today.

Syd junior and his mother May, behind the counter in the nineteen fifties.

A still from the silent film “Ebb Tide” starring Chili Bouchier with Syd in a cameo as himself.

In 1937 with electricity hooked up to the lamppost.

Jane Tothill

colour photographs © Sarah Ainslie

Charlie Burns, King of Bacon Street

You may not have seen Charlie Burns, the oldest man on Brick Lane, but I can guarantee that he has seen you. Seven days a week, Charlie, who is ninety four years old, sits in the passenger seat of a car in Bacon St for half of each day, watching people come and go in Brick Lane. The windscreen is a frame through which Charlie observes the world with undying fascination and it offers a deep perspective upon time and memory, in which the past and present mingle to create a compelling vision that is his alone.

For a couple of hours yesterday, I sat in the front seat beside Charlie, following the line of his gaze and, with the benefit of a few explanations, I was able to share some fleeting glimpses of his world. The car, which belongs to Charlie’s daughter Carol, is always parked a few yards into Bacon St, outside the family business, C.E. Burns & Sons, where they deal in second hand furniture and paper goods. Carol runs this from a garden shed constructed inside the warehouse, and lined with a rich collage of family photographs, while Charlie presides upon the passage of custom from the curbside.

Many passersby do not even the notice the man in the anonymous car who sits impassive like Old Father Time, taking it all in. Yet to those who live and work in these streets, Charlie is a figure who commands the utmost respect and, as I sat with Charlie, our conversation was constantly punctuated by a stream of affectionate greetings from those that pay due reverence to the king of Bacon St, the man who has been there since 1915.

The major landmark upon the landscape of Charlie’s vision is a new white building on the section of Bacon St across the other side of Brick Lane. But Charlie does not see what stands there today, he sees the building which stood there before, where he grew up with his brothers Alfie, Harry and Teddy, and his sister, Marie – and where the whole family worked together in the waste paper merchants’ business started by Charlie’s grandfather John in 1864.

“We lived on this street all our life. We were city people. We all grew up here. We were making our way. We were paper merchants. We all went round collecting in the City of London and we sold it to Limehouse Paper Mills. There was no living in it. Prices were zero. Eventually we went broke, but we still carried on because it was what we did. Then, in 1934, prices picked up. We were moving forward, up and up and up. We carried on through the war. We never stopped. This was my life. We used to own most of the houses in this street. They were worth nothing then. They couldn’t give them away.”

Once the business grew profitable, the family became involved in boxing, the sport that was the defining passion of the Burns brothers, who enjoyed a longstanding involvement with the Repton Boxing Club in Cheshire St where Tony Burns, Charlie’s nephew, is chief coach today.

“Somehow or other, we got into boxing and then we were running the Bethnal Green Men’s Club and then we took a floor in a pub. We were unstoppable. We used to box the Racing Men’s Club. We used to box at Epsom with all the top jockeys. We made the Repton Boxing Club. I was president for twenty years and I took them to the top of the world. When we joined there was only one boy in the club. (He still comes over and sees me.) We built them up, my brothers, myself and friends. They all done a little bit of boxing.

We had some wonderful boxers come here. They were all poor people in them days, they were only too glad to get into something. We used to take all the kids with nothing and get them boxing. They played some strokes but they never did anything bad. Everything we done was for charity. We were young people and we were business people and we had money to burn.

All of the notorious people used to come to our shows at the York Hall. We had the Kray brothers and Judy Garland and Liberace. I remember the first time I met Tom Mix, the famous cowboy from the silent films. We met all the top people because this was the place to be. I had a private audience with the Pope and he gave me a gold medal because of all the work we did for charity.”

You would think that the present day might seem disappointing by contrast with vibrant memories like these, but Charlie sits placidly in the front seat of the parked car every day, fascinated by the minutiae of the contemporary world and at home at the centre of his Bacon St universe.

“This place, years ago, was one of the toughest places there was, but one of the best places to be.” he announced, and I could not tell if Charlie was talking to himself, or to me, or the windscreen, until he charged me with the rhetorical question, “Where else can you go these days?” I was stumped to give Charlie a credible reply. Instead, I peered through the windscreen at the empty street, considering everything he had said, as if in expectation that Charlie’s enraptured version of Bacon St might become available to me too.

Charlie reminded me again,“We were paper merchants. We were moving forward.”, as he did several times during our conversation, recalling an emotional mantra that had become indelibly printed in his mind. It was an incontestable truth. We were King Lear and his fool sitting in a car beside Brick Lane. Becoming aware of my lone reverie, Charlie turned to reassure me. “I’ll get some of the boys round for a chat and we’ll go into it in depth,” he promised, with quiet largesse, his eyes glistening and thinking back over all he had told me,”This is just a little bit for starters”.

On the wall of Carol’s shed, in the yellowed photo at the centre, taken in Bacon St in 1951, you can see Charlie’s brothers Alfie and Teddy, with Charlie on the right.

The Burns family in 1951, with Charlie again in the right.

The redoubtable Carol Burns in her shed with the photo of her Uncle Tony, president of the Repton Boxing Club, being honoured by the Queen.

Charlie’s good friend and neighbour Asad Khan sent in this photo of the two of them together.

Nathaniel's latest discoveries

If you should find yourself at a loose end in Shoreditch on a rainy Saturday afternoon, the very best thing you could do is to drop in to M.Goldstein, the quirky antique shop in the Hackney Rd where you can always be assured of engaging conversation and an intriguing display of Nathaniel Lee-Jones‘ latest unexpected discoveries.

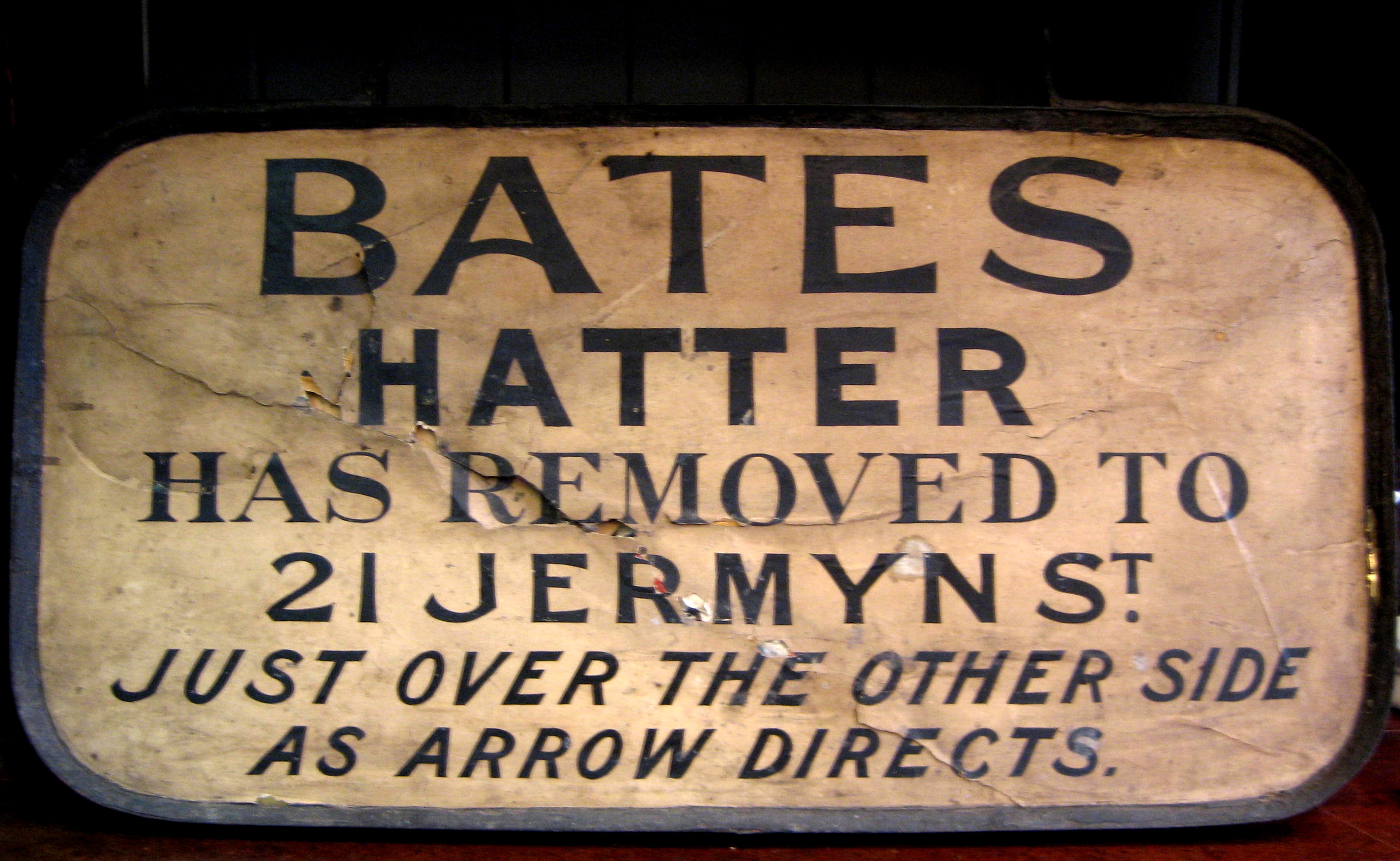

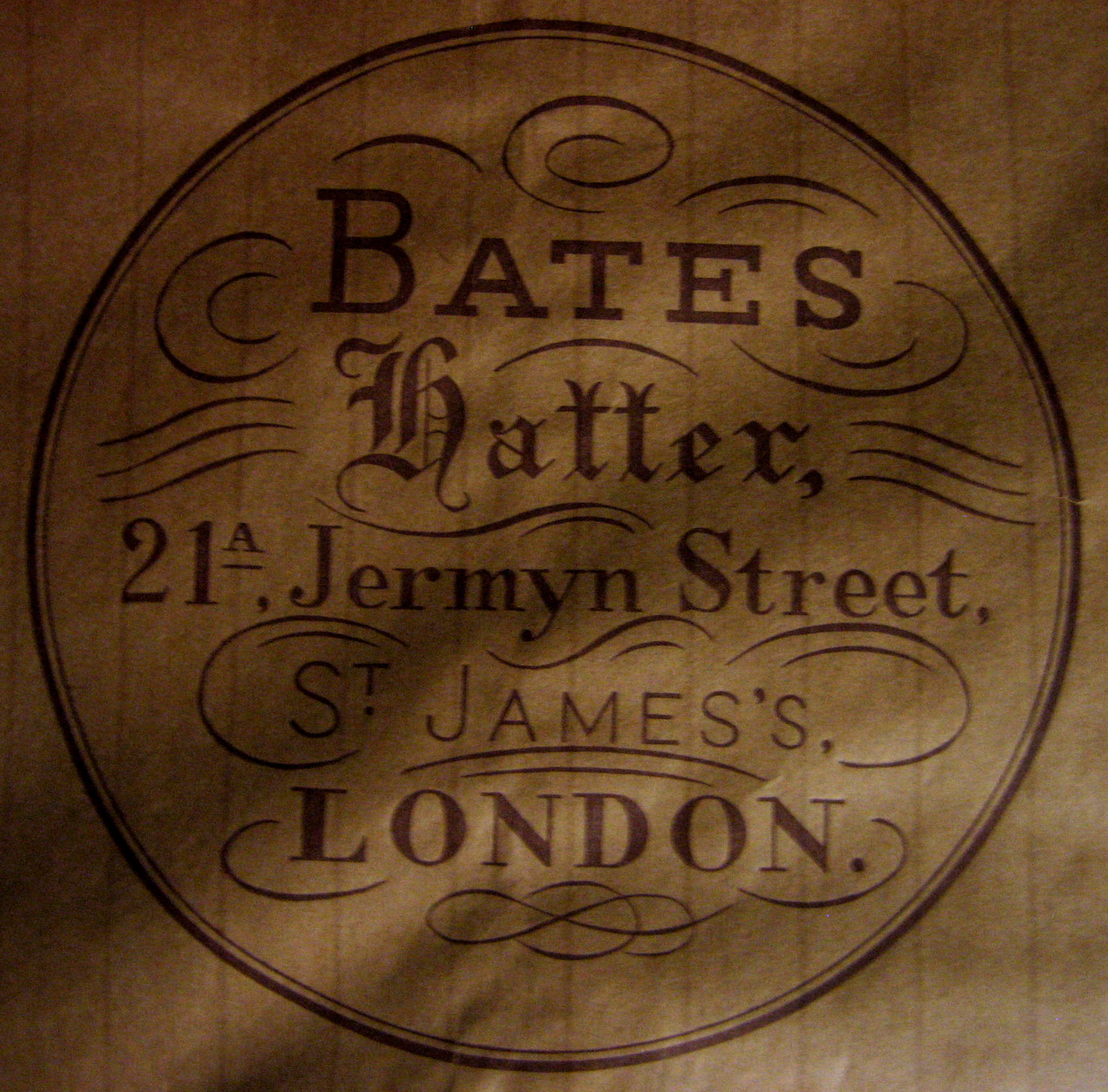

With a glance at the cheery illuminated golden “M” from McDonalds in the window, I stepped from the drizzle into the narrow shop where Nathaniel has just installed the fixtures and fittings he salvaged from Bates, the Hatter of Jermyn St, now the company has been sold to Hilditch & Key, the shirtmakers. On one side, Pippa Brooks, Nathaniel’s wife and business partner, nimbly perched upon an old iron bench from Regent’s Park Zoo and engaged in animated chat with a pal, while opposite Nathaniel was happily preoccupied, rearranging his beloved trophies upon the mahogany shelves that he has rescued from one of St James’ most famous shops – thanks to his extensive and mysterious connections in Mayfair, Soho and the West End.

It was a charming scene, and I was a willing audience as Nathaniel started talking, cheeks glowing and eyes sparkling in excitement at his recent acquisitions. Explaining that the staff of Bates, the venerable Hatter, have moved up Jermyn St to Hilditch & Key (taking their hats and their mascot, Binky the stuffed cat, with them), Nathaniel produced a string of treasures they left behind, the shelves, the cabinets, the canopy, the chandeliers, the bags and the signs. Opening up cupboards, he revealed all the press-cuttings and photos, lovingly pasted there, recording the actors, celebrities, military and royalty who have worn Bates’ hats over the years. These are cabinets that held the hats that crowned the famous.

Turning from these items that speak of the elevated clientele of a West End hatter, my eye fell upon a hat with an entirely different history. A nineteenth century Billingsgate market porter’s hat, which Nathaniel also acquired recently. A utilitarian style of headgear that exists beyond the range even of Bates’ extensive collection. With a flat top designed to balance fish crates upon, made of thick leather on a wooden base, and held together by hobnails and bitumen, it is an astounding sculptural object. The deep channel within the brim was designed to catch any water that might spill from a fish crate and Nathaniel explained that if these hats sprang leaks, the skin of a Dover sole was used to seal the holes.

Nathaniel bought the porter’s hat from a photograph, bidding over the phone, from an auction house in the North, and a surprise awaited him when it arrived and he put it on. “It fits me like a glove!”, Nathaniel declared in triumph, snatching the lumpy black hat from its stand and placing it upon his head with an exultant grin to illustrate the point, and, in doing so, producing a painterly image that evoked another century and another world.

I was fascinated to hold the market porter’s hat in my hands and see it close up, nearer to the weight of a helmet that a hat, it was nevertheless expertly balanced. The purposeful yet irregular shapes of leather that enfolded the crown creating curved ridges, lined with heads of gleaming hobnails and daubed with layers of bitumen to create a form and surface that was distinctly fishlike. There was bare wood inside the hat and upon the worn flat top, where the boxes sat. As much as the hat bore evidence of use, it revealed careful maintenance too, because this was an essential piece of kit for a porter, whose livelihood depended on it. No longer manufactured after 1957, Nathaniel wondered if it might be rare, though since the word went round, several porters have rung to claim, “I’ve got one too!”

In a flash of inspiration, Nathaniel has a plan – the Billingsgate porter’s hat is to become the first of a display of different headgear to fill the glass-fronted cabinets from Bates, which are designed to show hats. I could already sense the excitement as he explained his vision and, since he has an incomparable genius for seeking out unlikely and wonderful things, in future I shall keep my eye upon M.Goldstein, awaiting the latest discoveries in Nathaniel’s hat collection.

Nathaniel in his nineteenth century Billingsgate porter’s hat

A Billingsgate porter photographed by Bill Brandt in 1936

Columbia Road Market 34

For just £3 I bought this magnificent pelargonium The Marquess of Bute from Lyndon this morning at Columbia Rd. This particular pelargonium with its satin petals in deep sensuous Victorian tones has been a star of the market scene over many recent Summers. I bought some two years ago which I enjoyed over two successive Summers before they became casualties of last Winter.

Lyndon, who hails from New Zealand and always has one of the most reliably interesting selections of plants in the market, told me that it was bred by the wealthy nineteenth century industrialist John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute, who used the coal from his Welsh mines to heat his glasshouses where he employed some of the greatest botanists of the day. Apparently, the deep crimson hue with its paler trim is bred to evoke the ecclesiastical tones of a Cardinal. The Marquess whose interests included medievalism, the occult and linguistics, as well as horticulture, and whom Lyndon alleges was the lover of the Princess of Wales, entered into partnership with the great architect William Burges to create two of the finest buildings of the late Gothic revival, Cardiff Castle and Castle Coch.

Henceforth, I shall nurture this pelargonium on my kitchen window sill to encourage lush Victorian fantasies of my own, while I am washing the dishes.

Bill the Ostler of Spread Eagle Yard

Last week, I wrote about Pearl Binder, the artist and writer, who lived in the seemingly idyllic Spread Eagle Yard in Aldgate during the nineteen twenties and thirties while studying at the Central School of Art. Binder was a life-long socialist, whose political beliefs were informed by her formative experiences in the East End.

This week, I am publishing these excerpts from her pen portrait of Bill the Ostler, who with his wife Emmie, was Pearl Binder’s neighbour in Spread Eagle Yard. It was originally included in her book “Odd Jobs”” published in 1935. This is a plain story, revealing the effects of the shift from horsepower to the petrol engine upon the life of a modest couple with little control over their destinies. A tale of the shifting labour market as a consequence of industrial and technological change, that became all too familiar as the century wore on, but no less devastating for those at the mercy of these changes.

Pearl Binder’s self-effacing protagonists, like Arnold Bennett’s dignified characters, draw us to empathise with feelings that are all the more poignant for being understated or withheld.

Bill began work as a butter-slapper in the local branch of the Home and Colonial. Later he drifted into driving vans for one of the City straw merchants. After twenty-five years of van-driving, his feet had become so crippled that the Governor gave him the job of Ostler instead.

As Ostler, Bill, together with his wife Emmie, was sent to live in the horse-keeper’s cottage in the Governor’s straw yard. He applied himself to his new job with patient industry, spreading his affection for his own horse over twelve. His duties consisted in feeding and grooming the twelve cart-horses, cleaning the stables after the last load of hay had been weighed and stacked in the hay-loft and acting as a caretaker when the office was closed. He received a small wage and lived rent-free.

The proud heraldic eagle, which gave the Yard its name, spread its stone wings above the big clock in the north wall of the Yard. Over a hundred years ago, the clock had stopped at twenty-five minutes past nine. The Yard had once been the inn yard of the old Spread Eagle Inn.

The sweet smell of the hay in the lofts and the peaceful cooing of the pigeons in the Yard seemed so remote from the cosmopolitan roaring of the City, just outside the gate, that Emmie used to imagine herself in the country. In the cool of the evening, Bill would take his stumpy pipe and sit outside the Yard, in the door-way of the big gate, watching the swirling life of the city go by and resting his aching feet after his day’s work.

He never tired of the endless procession: modish little Jewesses from Whitechapel escorted by bold-eyed sweethearts with bravely padded shoulders, noisy children from Leman Street, their smooth Egyptian heads sticking precociously above English gymnasium tunics and cheap Norfolk suits, sad-eyed Malay sailors on their way to the East India Dock Rd, swarthy turbaned Lascars carrying brand-new cardboard suit-cases, argumentative Irish labourers on their way to Shadwell public houses, silent Chinese from Pennyfields, hurried businessmen from the City, and the rector from St Mary’s.

Early in June, the governor’s clerk informed Bill that the business was closing down and that the Yard was going to be let. The increasing motor traffic was making the sale of hay unprofitable.

The sun shone dazzlingly in the Yard on the day of the auction, and the heavy air, pungent with hay barely stirred. Bill had risen especially early to sweep and sand the Yard. Lovingly he groomed the horses to immaculate satin, and in their fine tails he plaited braids of straw.

The sale began. One by one, Bill led out the gleaming cart-horses for inspection, each with a numbered paper disc newly stuck on its flank. When all the horses had been sold, the carts were quickly knocked down. After that the bales of hay were disposed of in an off-hand manner, as though of little significance.

The Governor said that they could go on living in the cottage, for the time being at least. The Yard itself was not yet sold. In the meantime, they could remain there and keep an eye on the place. But no wages. He advised Bill to apply for the dole. When the dreadful day came to sign on at the Labour Exchange, he was so ashamed and nervous that he could hardly hold the pen in his hand to write.

Emmie tried to be cheerful. She vowed that Bill would soon be in work again. His character and his copperplate handwriting were in his favour. But he was getting on for sixty and his feet were against him. She tried to persuade him to take a walk every day, for the good of his health, across Tower Bridge towards Bermondsey, or in the other direction as far as the Whitechapel Library, where the workless men crowded outside the entrance round the Want ads, displayed under a wire frame.

November saw the hasty installation of a fun fair. The Yard buildings suffered the indignity of orange-coloured paint. The proud stone creature above the silent clock was daubed with aluminium. Ringed round with electric globes, the clock itself stared down from this disguise, its hands fixed immovably at nine-twenty-five. The cottage was festooned with coloured electric lights, and even Emmie’s sandstoned front step, hollowed out by two hundred years of footsteps, was smeared over with silver paint. The whole Yard looked startled and outraged like a dignified old lady forcibly tricked into wearing flashy modern clothes.

The fun fair opened at last. The twentieth century swarmed in from the street and ran riot over the eighteenth. Outside the gate glittered LUNAPARK in red and white electric bulbs, and inside the Yard blazed with coloured points of light, containing here and there a sudden blank where the hasty work had fused. The alley entrance to the Yard was decorated with a row of wildly distorting mirrors, which proved such a big attraction that the gangway was constantly blocked. Bill did not like the invasion. His dignity and his quiet were gone. There was no more smell of horses in the Yard.

The new boss promised to give Bill some sort of job when the fair started. The white faced boy asked Emmie if she could provide him with a bite of dinner each day. He could afford sixpence. Emmie contrived to cook up a daily plateful of meat and vegetables, which the boy fell upon ravenously. In between mouthfuls, he informed her that his father had been dead some years and that he, being the eldest of six children, was the mainstay of his mother. He said he had been at work four years already and was seventeen.

The scattered morsels of food presently attracted swarms of hungry rats, and the boss, cursing at the expense, ordered Bill to put rat poison in all the corners. Bill’s new job was to sweep up the Yard every night when the fair ended and to act as caretaker at all times. Wages one pound a week, less insurance, and the cottage rent free again. Little as it was, he and Emmie were both deeply relieved. It was less than the dole, but more respectable.

With the loss of his job as an Ostler, separated from his intimate working relationship with horses, Bill became an anachronism of an ancient world, and, in retrospect, the Lunapark funfair reads as both emblematic and prophetic of the modern world. His story is a fable that stands for a million other personal tragedies of dislocation that continue around us today, whenever the lives of small people are sacrificed to big changes beyond their control.

All this Pearl Binder witnessed in the place she first took lodgings when she came to the London as a young woman, the fate of Spread Eagle Yard – the hay yard that became a theme park – was a microcosm of the twentieth century itself.

Bill the Ostler