At Sandys Row Synagogue

Here is Mr Sender Chaim, always the last to leave after the lunchtime service at Sandys Row. On his way out he touches the box on the door frame which contains the Mezuzah, a scroll with two chapters of the Torah written in Hebrew to be recited daily.

This is one of thousands of intimate photographs taken by Jeremy Freedman over the last five years, documenting his growing involvement with Sandys Row, the oldest surviving Ashkenazi community in London and the only remaining synagogue in Spitalfields. Jeremy’s great-great-great-great-grandfather was one of the founders of the synagogue in 1854, but it was the death of his grandfather Alfred Freedman, the last president of the synagogue, which brought Jeremy back here in July 2005 – where five generations of his family have been before him.

A week after the funeral, Jeremy’s father Henry Freedman called an Extraordinary General Meeting to discuss the future of the shul which had dwindling attendances and a decaying building, and it was at this sombre gathering that Jeremy took his very first photograph in the synagogue, which you can see below. Henry Freedman is at the centre of the photo, and to the left in the dark cap is Jimmy Wilder who had been treasurer of the synagogue for seventeen years. “It was a catharsis,” admitted Jeremy, “As I took pictures, I realised that the majority of the board members were over sixty, many much older, and that nothing could happen unless a new generation got involved.”

Seeking to explore his own family’s past, Jeremy went down into the cellar, his feet sinking into the dust gathered like sand on the beach, making the first footprints in a generation. There he discovered a forgotten vault for the burial of religious documents containing Torah scrolls from the beginning of the community and, under debris, Jeremy found a relic that halted his photography. It was a forgotten vellum commemorating those who paid for the refurbishment of the synagogue a century earlier, in the promise that the acknowledgement of their work would always hang in the vestry.

Six months later, a broken water tank in the caretaker’s flat caused a flood that almost brought down the vestry ceiling. An accident which hastened the imperative for renewal, yet also revealed more of the history of the shul, as Jeremy explained,“We had to empty out the vestry before it was refitted. It took several weekends to clear the contents accumulated over a hundred years, books, letters, ledgers – some written in Dutch, indicative of the origins of past members of the shul. We even found a prayerbook dated 1680, produced by appointment to the Austro-Hungarian Emperor.”

Now the vestry has been refurbished and the vellum’s place is secured, indicative that the reins have been passed to a new generation – as the synagogue looks to the future, celebrating weddings and barmitzvahs with increasing attendances, and anticipating the renovation of the roof funded by English Heritage in time for the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the building’s construction. With a quiet emotionalism, Jeremy’s subtle photographs record this transition through the eyes of a participant, while also honouring those senior members, many of whom have passed away in these five years, yet remembered today for keeping the Sandys Row synagogue open when all the others in Spitalfields closed.

The crisis meeting at the synagogue in July 2005.

Barry Pash is the fourth generation of his family to worship at Sandys Row. A gentle man, once a photographer for a London newspaper, Jeremy took this picture of Barry in the flat where he lives alone in Petticoat Tower, Petticoat Lane.

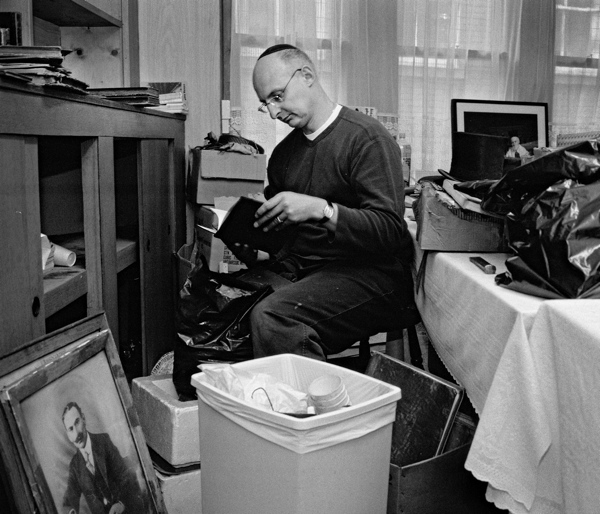

Michael Davidson, a scholar from an orthodox background, sifts through a century of accumulated books and documents in the vestry after the flood of 2006.

Stella Wilder (widow of Jimmy Wilder, the treasurer, whose picture is to be seen on the right) was the secretary of the Sandys Row synagogue for seventeen years until 2005. Born in Old St, she once worked for British Overseas Airways Corporation at their office there and, in spite of her fading sight, still takes huge pleasure today in watching the planes cross the sky, seen from the window of her flat nearby in the Golden Lanes Estate.

For the first time, Misha is summoned to carry the Torah that he will read at his Barmitzvah, as part of the ritual of becoming a man enacted by his forefathers.

Joe Listner, who used to run the shul, examining the vellum of 1905 discovered in the basement.

Many years ago, Milton who has resided and worked in the locality his whole life, celebrated his marriage here at Sandys Row.

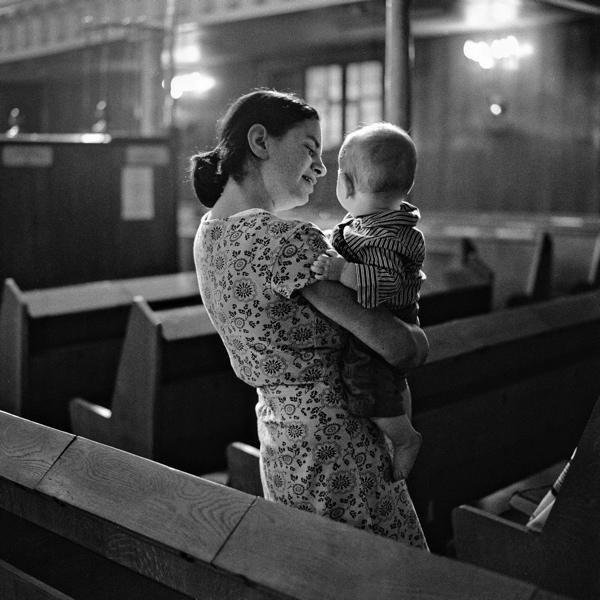

For fifteen years there were no marriages at Sandys Row, then there were three in a year, and now young families are joining the synagogue, as Jewish people move back into the neighbourhood for the first time in a generation.

You can read further about Sandys Row Synagogue and see more of Jeremy Freedman’s portraits of the senior members of the shul here: Jeremy Freedman, photographer

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Spitalfields Antique Market 14

This is Justin Melican, an agreeable young actor of antipodean origin who enjoys selling kitschy collectables when he is not working. “I’m just back from Cambodia, shooting an episode of an American TV docudrama, playing a drug trafficker,” he let slip with deeply impressive indifference – as if this was something everyone did – before explaining that he has just completed the first year of a three-year interior design course as well. “I’m juggling everything at the moment!” he declared, brimming with the bright energy, bold schemes and winning charisma of one eager to discover his destined place in the world.

This is the gracious Sonoe Sugawara, seen here proudly holding an exquisite nineteenth century girl’s silk undergarment. Sonoe originally sold vintage English clothes from a stall in a Tokyo department store and now has a clever business going whereby she sells kimonos in London too, moving back and forth two or three times a year with a full suitcase in both directions. “My boyfriend’s great-grandparents were dealers before the war, collecting nineteenth and early twentieth century kimonos,” revealed Sonoe with a signficant nod, accounting for the origins of her ravishingly beautiful stock of fine antique kimonos.

This is Matthew Mcfarlane, a free-thinking one man band who enjoys the community here as much as the selling. “I can leave my stall unattended and no one will touch it,” he vouched confidently. Matthew modestly contends his stall offers him a day off from his work as a set builder and designer of shop windows, but I could see he possesses a good eye – and the rescued chairs he has reinvented (to be seen on his blog Sew Watless) testify to a cunning ingenious sensibility. “There is something hauntingly beautiful about dishevelled furniture, left to waste, yet with so much more to give.” he added, revealing his true soulful self.

This is Jennie Sedwell, Heather Sedwell and Lesley Willis – not sisters as you might assume, but in fact three generations who work happily together selling a breathtaking range of vintage textiles, clothing and haberdashery. Lesley has done it as a hobby for twenty-five years, while her mother Jennie joined ten years ago and daughter Heather completed the trio on leaving school. “It was ridiculous!” exclaimed Lesley, “We used to have twelve stalls – as much stock as a big shop – and a van with a mirror for a changing room. We didn’t even have time to sit down, whereas now unfortunately…”, protesting in appealingly overemphatic self-deprecation, whilst still presiding over one of the busiest stalls in the market.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

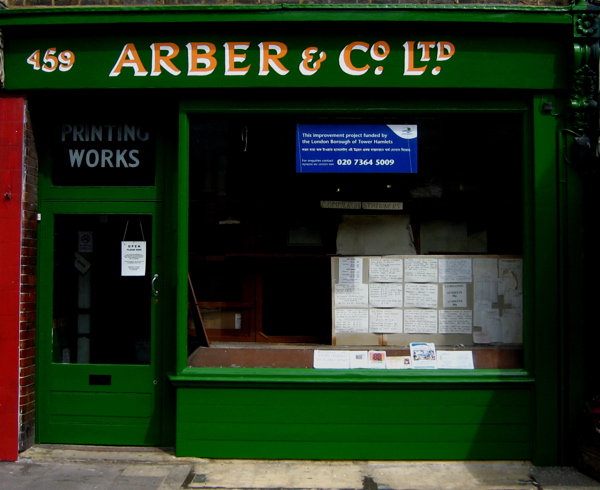

Return to W. F. Arber & Co, Printing Works

There have been changes at W.F.Arber & Co Ltd (the printing works opened by Gary Arber’s grandfather in 1897 in the Roman Rd) since I was last here in February. At that time, Gary was repairing the sash windows on the upper floors, replacing rotten timber and reassembling the frames with superlative skill. This Spring, Gary was the recipient of a small grant from the Olympic fund for the refurbishment of his shop front, which had not seen a lick of new paint since Gary last painted it in 1965.

The contractors were responsible for the fresh coat of green but Gary climbed up a ladder and repainted the elegant lettering himself with a fine brush, delicately tracing the outline of the letters from the originals, just visible through the new paint. This was exactly what he did once before, in 1965, tracing the lettering from its first incarnation in 1947, when the frontage was spruced up to repair damage sustained during the war.

No doubt the Olympic committee can sleep peacefully in their beds now, confident that the reputation of our nation will not be brought down by shabby paintwork on the front of W.F.Arber’s Printing Shop, glimpsed by international athletes making their way along the Roman Rd to compete in the Olympics at Stratford in 2012. Equally, Gary is happy with his nifty new paint job and so all parties are pleased with this textbook example of the fulfilment of the ambitious rhetoric of regeneration in East London which the Olympics promises.

If you look closely, you will see that the glass bricks in the pavement have been concreted over. When Gary found they were cracking and there was a risk of some passerby falling eight feet down into the subterranean printing works, he obtained quotes from builders to repair them. Unwilling to pay the price of over five thousand pounds suggested – with astounding initiative, Gary did the work himself. He set up a concrete mixer in the basement printing shop, filled the void beneath the glass bricks with rubble, constructed a new wall between the building and the street, and carried all the materials down the narrow wooden cellar stairs in a bucket, alone. Gary’s accomplishments fill me with awe, for his enterprising nature, undaunted resilience and repertoire of skills.

“I shouldn’t be alive,” said Gary with a wry melancholic smile, referring not to his advanced years but to a close encounter with a doodle bug, while walking on his way down the road to school during the war, “The engine cut, which means it was about to explode and I could see it was coming straight for me, but then the wind caught it and blew it to one side. We lost all the glass in the explosion! Another day, my friend David Strudwick and I were eyeballed by the pilots of two Fokker Wolf 190s. We saw them looking down at us but they didn’t fire. – David joined the airforce at the same time I did, he flew Nimrods and died many years later, while making a home run during a cricket match in Devon.”

These thoughts of mortality were a sombre counterpoint to the benign season of the year. Leading Gary to recall the happy day his father and grandfather walked out of the printing works at dawn one Summer’s morning and, in their enthusiasm for walking, did not stop until they got to Brighton where they caught the train home, having walked sixty miles in approximately twelve hours.

In those days, Gary’s uncles Len and Albert, worked alongside Gary’s father and grandfather here in the print shop, when it was a going concern with six printing presses operating at once. Albert was an auxiliary reserve fireman who was killed in the London blitz and never lived to see his baby daughter born. Gary told me how Albert worked as a printer by day and as a fireman every night, until he was buried hastily in the City of London in an eight person grave. “I don’t know when he slept!” added Gary contemplatively. There was no trace of the grave when Gary went back to look for it, but now Albert is commemorated by a plaque at the corner of Althelstan Grove and St Stephen’s Rd.

Whenever I have the privilege of speaking with Gary, his conversation always spirals off in fascinating tangents that colour my experience of contemporary life, proposing a broad new perspective upon the petty obsessions of the day. My sense of proportion is restored. This is why I find it such a consolation to come here, and leads me to understand why Gary never wants to retire. Each of Gary’s resonant tales serve to explain why this printing shop is special, as the location of so much family and professional life, connected intimately to the great events of history, all of which remains present for Gary in this charmed location.

Now that Gary is a sole operator, with only one press functional, he is scaling back the printing operations. And I joined him as he was taking down the printing samples from the wall where they have been for over half a century, since somebody pasted them onto some cheap paper as a temporary measure. It was the scrutiny of these printing specimens that occasioned the reminiscences outlined above. Although these few samples comprise the only archive of Arber’s printing works, yet even these modest scraps of paper have stories to tell, of businesses long gone, because Gary remembers many of the proprietors vividly as his erstwhile customers.

I was fascinated by the letters ADV, indicating the Bethnal Green exchange, which prefix the telephone numbers on many of these papers. Gary explained this was created when smart people who lived in the big houses in Bow Rd objected to having BET for Bethnal Green, which they thought was rather lower class, on their notepaper. There were letters to the Times and a standoff with the Post Office, until the local schoolmaster worked out that dialling BET was the same as dialling ADV – which might be taken to stand for ‘advance’ indicating a widely-held optimistic belief in progress, which everyone could embrace. So just like Gary’s Olympic paint job, all parties were satisfied and looked to the future with hope.

“Bill Newman of Advance Insulation used to be covered in white asbestos powder. The whole place was like a flour mill! He smoked a fat cigar which we thought was the cause of the cancer that killed him, but later we learnt the truth. The Victoria Box Company closed in the nineteen sixties after a woman had her fingers cut off by a tin pressing machine and the compensation claim shut the company down. Mr Courcha was around in the nineteen fifties, he had a huge lump on his bald head like something out of a comic. We had three generations of Meggs chimney sweeps until the introduction of the smokeless zone finished them off.”

“Sollash made boxes, the factory took up four or five shops in the Hackney Rd but they packed up when Mr Sollash got old. You see that bull on the Bull Hotel notepaper, that was the bull we used on butcher’s bills! ‘Dr.’ means ‘debtor’, it was standard on invoices then.”

“This is a World War II ration card from Osborne the Butcher. Harry Osborne was a German who changed his name during World War I, his son Len ran the business until he retired in the nineteen seventies.”

You may like to read about my previous visits to Gary Arber’s printing works:

Jo & Sheba Eferoghene, Novo Fashions

Many times I have dawdled in Wentworth St to marvel at the wonderful range of dazzling African fabrics on sale in the specialist shops that line this street, drawing me with their powerful allure, every one presided over by charismatic sassy ladies who are both the proprietors and style exemplars in this glamorous world of “wax” and “lace.”

Since 1608, this neighbourhood has been known as “Petticoat Lane” on account of the textile and clothing markets here and, even though the name was changed in 1830, this is still how it is referred to. Where once Huguenot weavers wove cloth in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in a location that was heart of the Jewish clothing industry in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, today it is Nigerian and Ghanaian women that uphold the traditional identity of these streets as a centre for textiles. They have made it the pre-eminent destination in London for the variety and quality of African fabric on sale here.

So it was a rare pleasure for me when Trevor of Liverpool St Chicken (that I wrote about in February) introduced me to Jo & Sheba Eferoghene, two vivacious sisters who run Novo Fashions at the corner of Wentworth and Leyden St, a tiny treasure trove of a narrow shop stacked to the roof with every kind of colourful attractive fabric in pattern and lace. “My mother was a dealer in Nigeria, so we learnt it from her and it is something we both love to do,” confessed Sheba, her bright eyes – enhanced by eyeshadow in peacock shades – glittering in delight. She welcomed me graciously, gesturing freely to the dazzling kaleidoscopic displays lining every wall. “The African fabric, this is what we wear – and the demand is so great that there never can be too much!”, she declared in dignified celebration.

Next, Jo, the other half of this impressive duo, came to greet me from the rear of the shop – alive with charm, and emerging suddenly from the melee of vivid competing patterns resplendent in a poker dot dress. She explained that although as sisters they work together, Sheba takes more responsibility for the shop, while she, the senior, travels around the globe to buy the fabric. With the keen sensibility and shrewd authority of a born businesswoman, Jo sets out three times a year to visit the distant warehouses of the cloth salesmen who turn up in Wentworth St leaving their cards, because she wants to be certain of the quality of the fabric she is buying for her customers.

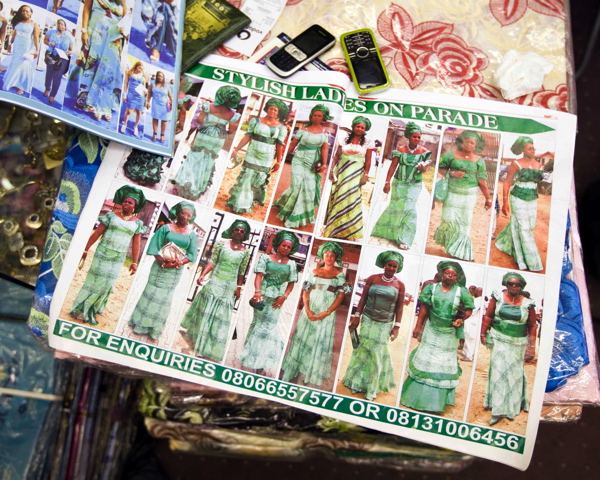

The biggest selling textile in Wentworth St is “wax” – meaning batik fabric, created using the technique whereby patterns are printed onto cloth in wax which resists dye. Elaborate designs are built up through successive layers of dying, forming bold geometric patterns in strong colours. It is indicative of our modern world that very little of this “African” fabric is from Africa, in fact the best “wax” originates from Holland. Sheba apprised me of this with professional expertise, laying out a length of lustrous mustard coloured cloth as an example of “Holland wax” manufactured by Vlisco in Helmond for the African market. China and Thailand also produce wax, and Sheba hauled specimens from the shelves creating an extravagant collage of coloured cloth for me to appreciate, before she revealed there is also an “English Wax,” though ironically this recently moved manufacture from Manchester to Ghana.

Cloth is sold in pre-cut lengths of six yards, sufficient to make an outfit. For a woman, six yards gives you two sarongs, a top and a scarf, or a boubou (long kaftan) plus a headscarf – whereas for a man, six yards is enough to make a buba (short kaftan) plus sokoto (trousers). Although the wax fabric is for everyday wear, Jo & Sheba also sell elaborate “lace” manufactured in Switzerland and Austria, expensive perforated cloth, sometimes richly embroidered and sequined, that is reserved for special occasions, weddings, birthdays and other celebrations.

Once you bear in mind that lace can be combined with wax in a single outfit, topped off with a contrasting cloth (a gele) tied around the head and also accessorized with costume jewellery, then you begin to realise the dizzying number of permutations that are presented by the fabrics in this tiny shop. This is where Jo & Sheba offer professional advice as stylists, because commonly people come to get fabric for an entire wedding party to dress everyone in toning outfits, yet with the most expensive cloth for the bride and groom. With so many different outfits for a single event, I can see that it takes a miracle of diplomacy to steer people away from potentially disastrous colour combinations towards a sympathetic scheme. Yet equally, the creative possibilities for mixing these patterns and vibrant tones are limitless.

Jo & Sheba Eferoghene have been trading in Wentworth St for eight years – dealing to neighbours and friends from their home before that – and through working together and demonstrating strength of character they have won loyal customers and built a reputation for discernment, crucial when the entire street is full of shops in direct competition. In the serious business of wax and lace, these two proud sisters know what they are talking about, and the photographs below of them modelling their own glorious fabric are absolute confirmation that they really know how to wear it too.

Sheba Eferoghene

Novo Fashions at the corner of Wentworth St and Leyden St.

The Eferoghene sisters, Jo, Helen & Sheba, celebrating Helen’s sixtieth birthday in their own fabrics.

Rose, Sheba & Jo at a wedding celebration for which Novo Fashions supplied the fabric.

Jo, Morayo, Rose & Sheba at a child’s tenth birthday party dressed in Novo Fashions’ fabrics.

New photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

The Boat Club photographic collection

Inspired by Lucinda Douglas-Menzies’ photo essay on the Victoria Model Steam Boat Club, I walked over to Victoria Park yesterday to meet Keith Reynolds, the secretary, a sympathetic man with an appealingly straggly moustache, who had agreed to let me take a look at the club’s photographic collection. So, as the members got steam up on the lakeside, I sat inside the club house and sifted through the archive, listening to all the variously enigmatic whistling and chugging sounds coming from the shore. Keith told me that the club existed even before the founding of the Model Steam Boat Club in 1904, preceded by a Model Sailing Boat Club that he believes was founded in 1875. The venerable club house dates from this period and Keith showed me where the lockers once were, custom-built to store huge model sail boats, before the age of steam took over.

There are just a handful of early black and white pictures, donated years ago by member Olive Cotman. The photograph above is from January 3rd 1937, but the earlier one at the top is tantalizingly undated. As well as the impressive display of model boats in both photographs, the members display a fine selection of hats, and in the top picture, if you look closely, you can see the pennant-shaped club badge pinned onto many of the caps. The dignity of these men, so serious with their moustaches and caps yet so proud to be photographed with their fleet of model steam boats, is very touching. I presume these boats were miniature versions of the vessels that you might see a mile away on the Thames at that time. By contrast, the diversity of the 1937 picture draws you into a relationship with individuals in the crowd, who braved the chill wind of Victoria Park in January to watch the model boats. The anonymous schoolboy in his cap is more interested in the camera than the boats, he gazes towards us and into eternity.

As I looked through the many thousands of photographs from the modern era taken by Janet Reynolds, Keith’s wife, over the thirty-five Summers since their marriage, I became fascinated by these idyllically beautiful colour pictures which tenderly evoke so many long happy Sunday afternoons. I realised that I was looking at images of the younger selves of those same members of the club who I had been introduced to that morning. Keith has been sailing steam boats for fifty years – since he was ten, although he had to wait until he was fourteen to become a full-fledged member in his own right, in 1964.

One day Keith’s father stopped by the lake to speak with the father of the current chairman Norman Lara, and that was how it began for the Reynolds family, which has now been involved for four generations. “She married into the Boating Club,” admitted Keith affectionately, referring to the induction of his wife Jan, “She took photographs because she didn’t want to boat, but then she decided it was more fun to get involved, and now my daughter and my grandson of fourteen are also members.” I was intrigued by Keith’s statement, revealing the narrative behind these lyrical images, which were taken by a photographer who became seduced by this diminutive nautical sport, embracing it as a family endeavour to entertain successive generations.

Out on the shore, Keith introduced me to the engineer Phil Abbott who showed me the oldest vessel still in use, a steam-powered straight-racing boat with the chic melancholic name of “All alone” from 1920, beside it sat “Yvonne” a high-speed steam-powered straight-racing boat from 1947. These boats speak of the different eras of their manufacture,“All alone,” with its brass funnels and tones of brown with an eau-de-nil interior, possesses a quiet twenties elegance in direct contrast to the snazzy red and beige forties colour scheme of the speed boat, that raises its prow arrogantly in the water as it roars along.

“All alone” was made by Arthur Perkins, who offered it to the club, as many members do, before his demise. “Yvonne” has a similar provenance. And when Keith explained that he had acquired half of the thirty-seven boats he possessed, making the others himself, I began to wonder if perhaps the focus of the club was the boats rather than the members. They are in effect mere custodians, providing maintenance for these vessels, enabling them to sail on, across Victoria Park Boating Lake, over decades and through generations.

Keith pinned a blue and white pennant-shaped enamel club badge on my shirt, just like those in the photo at the very top, and confessed that the club is eager for new members. It does not matter if you do not have a boat, anyone is welcome to join the conversation at the lakeside, and guidance is offered if you want to buy or make your own vessel, he explained courteously. It would be the perfect excuse to spend every Sunday boating for the rest of your life and you would be joining the honoured ranks of men and women who have pursued this noble passtime since 1904 on the lake in Victoria Park. These treasured photographs speak for themselves.

Contact Keith Reynolds of the Victoria Model Steam Boat Club by email vmscvictoriapark@aol.com

Columbia Road Market 42

It is not my custom, on the whole, to buy cut flowers – but they are in such profusion now at the market, at such low prices, that I could not resist. In these baking days of high Summer there is something quite magical about walking from the blinding sunlight of the day into the cool of the dark rooms in the old house where flowers glow in the half-light. Last week, I bought three bunches of lush Peonies for just £5 that I replaced this morning with these Larkspur, two bunches for a fiver.

Like last week, I was on the lookout for plants that will thrive in a dry sunny location under my window. This week, I bought a white Scabious for £4 and a Geranium (cinerum Ballerina) for £6. Scabious reminds me of childhood holidays in Dorset where I first saw them growing wild on the chalky downs, and this white one will be an interesting compliment to the blue one I already have. The Geranium is of the evergreen perennial variety that grows close to the ground, again this will give an interesting contrast to the other Geraniums I have in pink and blue, and some with dark foliage. The delicate lilac pink flowers, with intricate dark veins and neat diminutive leaves, of this particular variety, appealed to me.

My East End Photography Competition

Spitalfields Life was one of the winners in the My East End Photography Competition – for this portrait of Gary Arber the third generation printer, that I took in February in the comp room of the printing works in Roman Rd, opened by Gary’s grandfather Walter Francis Arber in 1897, where once the Suffragettes’ handbills were printed. “I’m here under duress because I’m an airman,” Gary told me when I first met him, because he sacrificed a career flying Lincoln Bombers to take over the printing works when his father died in 1954. Presiding over this print shop of a century ago where the twentieth century passed through like a whirlwind, Gary still retains the nonchalant professionalism of a flying ace.

On Thursday night, I went over to meet Gary when he shut up shop at five thirty and we sauntered casually along together down the Roman Rd to the Four Corners centre for film and photography, for the opening of an exhibition of the winning photos, where at a small ceremony Gary graciously accepted the award on my behalf. Among over four hundred entries, there were a large number of interesting photographs that add up to an impressive panorama of the East End at this moment. After searching through all the entries, it is my pleasure to present this small personal selection of works that caught my eye. Other notable inclusions were pictures by Spitalfields Life contributing photographers Sarah Ainslie and Jeremy Freedman, Sarah’s portrait of John Wright in Shadwell and Jeremy’s picture of Sandys Row Synagogue at dawn.

The judges of the competition were Martin Parr, photographer, Steven Berkoff, actor, and Kate Edwards of the Guardian. Speaking for the judges, Steven Berkoff said, “The pictures that stuck out for me were the pictures that expressed the deepest humanity. There is something eternal about the East End – a toughness and sturdiness, a tremendous amount of tolerance to difficult times.”

Yilmaz the tailor, Leyla Guler

Ann & Kitty eating jellied eels at the Eid party, Micahel Jones

Family in Lounge, Mary Cavanagh

Meat Trolley, Ridley Rd Market, Dalston, Agnes Sanvito

Old Sailor in Brick Lane, Johnny Pitts

Hasidic jews blessing the sun at dawn in Clissold Park, Olivia Harris

East London Line workforce, Scott Cullen

Working Nights, Bella Felling

I worked on the locks at the docks for twenty years,Vince Felice

Looking East from Canary Wharf on a snowy day, Shamir Sangrajka

Scattered thoughts, Jourdan.