Spitalfields Antiques Market 21

This is Emma, who usually shares a stall, pictured here on her first day of going it alone. “I’m coming back after having my baby, Albert, a year and a half ago on Christmas Day,” she confided to me gingerly, pushing her long hair behind her ears as she summoned the confidence to reassert herself in the world. Emma’s collection of pressed flowers, papercuts, old stationery and life drawings make an intriguing display with a poetry all of its own. “They fit together to make a story, a little bit like a fairytale, but I don’t know what the story is yet…” she added with a cautious smile of anticipation.

This is Scott & Alan, two lads from Brentwood in Essex, discreetly shielding their stock of prehistoric antiquities from view. “After eighteen years of metal detecting and collecting, we started buying and selling,” explained Scott, eagerly holding up a coin minted by the Iceni tribe two thousand years ago, “I’ve been doing it since I was eleven and developed a passion for it.” Surveying their trove of coins dating from the Iron Age to the sixteenth century, beside Anglo-Saxon bridle mounts and strappings of bronze overlaid with gold, who could resist the mystery and allure of these precious trophies?

This is happy-go-lucky Natalie from Dalston cradling Brian, her favourite bear. “He looks like a Brian,” she informed me with inexplicable authority, “Not a martian or a dodo, as some have suggested, but a nineteen fifties homemade attempt at a bear.” Do not always expect to see Natalie here in the market, because, as she declared candidly, “It’s too much like hard work to do it every week.” Yet Natalie is no slacker.“The truth is I am more of a buyer than a seller,” she confessed later, “I get sentimentally attached to everything and I don’t want to sell any of it.”

This is Marcus Rixon, a supply teacher from Portsmouth whose life changed six weeks ago. “Someone gave me a cabinet, and I thought ‘I want to do it up,'” said Marcus, open-heartedly revealing the origin of his modest business enterprise, reclaiming old furniture that has been beaten up and knocked about, repairing and recycling it. “It’s just me, a garage and the Volvo at the moment!” he added with a carefree shrug, relishing this newly discovered freedom from the classroom and excited by the possibilities of his first day stalling out in Spitalfields Market.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

At the Boys' Club 86th Anniversary Dinner

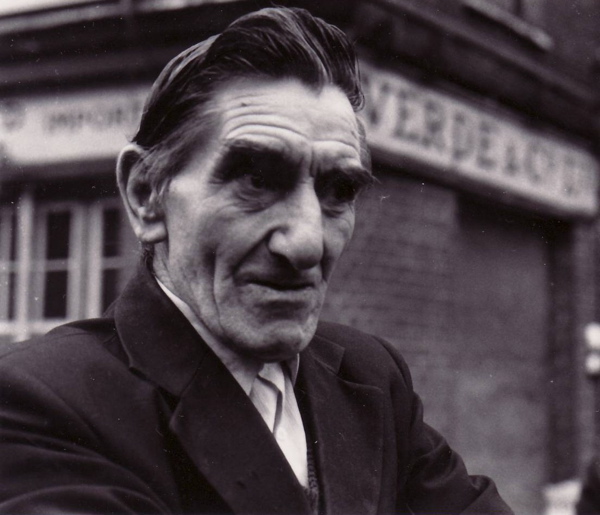

Last night, I had the delight of attending the Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys’ Club eighty-sixth anniversary dinner at the invitation of my new friend, club member Ron Goldstein. Entering the bar, I was immediately in the thick of a loud exuberant party of a hundred old boys in dark suits and club ties – the majority were octogenarians – all laughing and greeting each other flamboyantly in unselfconscious joy.

The rare spectacle of so many happy people together in one room stopped me in my tracks, it was sight to lift the heaviest heart. These were boys of modest origins who grew up on the Boundary Estate and in the surrounding streets of Bethnal Green and for whom the boys’ club (founded in 1924) offered a place of refuge where they could participate in cultural, educational and physical activities that served to raise their expectations of life. And many of the bonds of friendship formed there a lifetime ago exist to this day, as these lively reunions testify.

Aubrey Silkoff, the boy who wrote his name on the wall in Navarre St, Arnold Circus on the 19th April 1950, came to greet me. Like me, he was a newcomer attending his first reunion but already he was swept along by the emotion of the occasion. “I’ve just met people I haven’t seen for fifty years!” he declared with breathless excitement, introducing three childhood friends Alan Kane, David Goldsmith and Melvyn Burton who also wrote their names on the wall in 1950 when they used to play together. “We were happy in those days,” announced Alan, turning sentimental and speaking on behalf of his pals. “Do you know why? Because we hadn’t got a pot to piss in!” he continued, answering his own question, guffawing and breaking into the broadest smile, while the others exchanged fond satirical glances. Reunited, the excited dynamic of their childhood friendship took over and, as I cast my eyes around the room, I realised that while all these men lived as husbands, fathers and grandfathers in daily life, tonight they were free to be boys.

Once everyone was gathered, Maxie Lea MBE, the diminutive and playful club secretary, invited us to walk through into the dining room, where Ron and I took our seats at large round tables. Then Monty Meth MBE, the bright-eyed club chairman welcomed everyone, reading out apologies for absentees, saluting an old boy who had flown in from Dallas for the night and remembering those who had died since last year. Each name was received with cheers, applause and cheerful hammering on the tables, with the greatest affectionate response reserved for those who were here last year and all previous years, but who would never be seen again.

After a chicken dinner followed by chocolate gateau, Tony and Irving Hiller stood up to sing, providing the opportunity for everyone to express the sentiment that had been building up all evening. The gentleman next to me confided he had been friends with Tony – a talented songwriter who won the Eurovision Song Contest in 1976 – since they both met in kindergarten at the age of four, eighty years ago. All shyness and unfamiliarity were overcome now, bonds of friendship had been reaffirmed and it was time to play. Beginning with the club song (with new words to the tune of “Anchors Away”), providing the catalyst to release any lingering inhibitions, “So, as members of the best club of all/We’re shouting Cambridge/With a C-A-M-B-R-I-D-G-E/ Whizz bang, Whizz bang, Whizz bang rah/Who in the hell do you think we are?/C-A-M-B-R-I-D-G-E !” It was the cue for everyone to wave their hands, link arms, or stand and gyrate, re-enacting teenage idiosyncrasies and celebrating them in others, as distant memories of years ago came back to life. Although very little alcohol was drunk that night, everyone was high on emotion. A sense of mortality intensified the delight for some, and in the midst of the skylarking and high jinks a few tears of happiness were discreetly wiped away.

Few of these men live in the East End anymore, although many grew up here before the blitz – in a world we perceive today through black and white photographs of terraces with children playing in the street. Quite literally, some of these men were those children in the photos. Yet in their hearts they all still live in the East End, as incarnated by the spirit of emotional generosity, decency and respect that was encouraged by the boys’ club and which forms the basis of their common understanding. It is not the same East End you and I know today, but it is an East End that has a vibrant existence between members of this generation whenever they come together. My experience of the Cambridge & Bethnal Green Boys’ Club reunion dinner was a living vision of the very best of this lost world.

Through my many conversations, I learnt that while they have achieved professional careers and some have been honoured for distinguished service in the forces, none was ashamed of their origin. All were eager to come and show their gratitude to the boys’ club that provided such a life-changing experience – because, as the years go by, they recognise the familiar sense of belonging together more than they can belong to the increasingly unfamiliar geographical space of the East End.

I shook hands with Aubrey Silkoff at the end of our first reunion dinner, and we both turned to the spectacle of multiple farewells that filled the room. “Everyone turned out well, didn’t they?” he said, nodding his head in approval as the quiet realisation came to him. I think he will be back next year.

Pictured in the top photograph, boyhood chums Des Gammon and Sidney Berns.

Joe and Simon Brandez, father and son, both old boys.

Ron Goldstein with boyhood pal Ben Lampert.

Alan Kane

Len Sanders with his grandson Scott, both old boys.

Michael Denton, the oldest boy of all at ninety seven years of age.

At Canvey Island

Each Summer, as a respite from Spitalfields, I take a day trip to the sea. Last year, I enjoyed a visit to Broadstairs, but this year, inspired by a brochure given to me by Gary Arber, I decided to be more adventurous and go to Canvey Island. Printed by W.F.Arber & Co Ltd in the nineteen twenties – when Gary’s grandfather Walter ran the shop, his father (also Walter) was the compositor and uncles Len and Albert ran the presses – this brochure seduced me with its lyrical prose.

“Canvey Island, owing to its unique position at the meeting place of fresh and salt waters, which continually wash its shores, enjoys a nascent air which is extraordinarily health-giving and invigorating, and is, indeed in this respect, possibly above all other places in the kingdom. Prominent physicians in our leading hospitals pay tribute to the properties of the air, by sending patients to the Island in preference to any other locality.”

Yet in spite of this irresistible account of the Island’s charms, when I told people in Spitalfields I was going to Canvey, they pulled long faces and declared, “You’re joking?” Undeterred by prejudice, I packed ham sandwiches in my satchel and set out from Fenchurch St Station with an open mind to discover Canvey Island for myself. Alighting at Benfleet, I crossed the River Ray to the Island arriving at the famous wall that reclaimed the land from the sea – constructed in the seventeenth century by three hundred dutch dyke diggers under the supervision of Cornelius Vermuyden.

“One of the first places the visitor will make for is the sea-wall, which he has undoubtedly heard a good deal about before coming to Canvey, and with which he will be anxious to make a closer acquaintance. The wall completely encircles the Island, and, following all its windings in and out, covers a distance of about eighteen miles.”

Since I had no map and had not been to Canvey before, Gary Arber’s brochure was my only guide. And so I set out along the wall where stonecrop and asters grew wild, buffered and blown by salt winds from the estuary. With a golf course to the landward side and salt marshes to the seaward side, that widened out into a vast open expanse stretching away towards Southend Pier on the horizon, it was an exhilarating prospect and I enjoyed the opportunity to fill my lungs with fresh sea air.

“The grand secret of the wonderful health-giving properties of the air is the evaporation from the “saltings,” during the time when the tides are out, which charges the air with ozone, which is thus constantly renewed and refreshed, making it extremely healthy, clean and bracing.”

Reaching Canvey Heights and looking back, the contrast between the hinterland crowded with bungalows and whimsical cottages, and the bare salt flats beyond the wall became vividly apparent. Many thousands before me, coming to escape from East London, had also been captivated by the Island romance that Canvey weaves – and I could understand their affection for this charmed Isle that proposes such a persuasive pastoral idyll, when resplendent beneath a sky of luminous blue.

“There is a charming freedom about life on Canvey which will appeal to most people whose work-a-day life has to be spent in towns or their suburbs. The change of scene is complete in every respect; streets, bricks and mortar, are replaced by bungalows of very varied designs and appearances”

Surrounding Canvey Heights, I found a neglected orchard of different varieties of plum trees all heavy with fruit, and filled my satchel with a selection of red, yellow and purple plums, before making my way to Rapkins Wharf with its magnificent old hulks nestled together in a forgotten creek. The Island breezes played upon the rigging like a wind harp, filling the boat yard with other-worldly music, where old sea salts sheltering amongst the array of rotting vessels. Next, turning the corner of the Island, I reached the shore facing the estuary and walking along the esplanade soon came to Concord Beach Paddling Pool where I joined the happy throng at the tea stall, spying the big ships that pass close by.

“All the vessels, bound to and from the large ports on the Thames, must pass Canvey, and thus a constant procession of all sizes can be watched with interest and pleasure, ploughing their lonely furrows through the waters. Monster ocean-going liners bound for the other side of the world, sailing vessels with their full rig of canvas spread, and, as the sun catches the sails, delighting the eye with one of the most haunting sights to be imagined – the estuary teems with interest at all times. Here one can realise that, despite the progress of motor and steam in water travel, there still remain a few ocean-going vessels under sail only.”

At the next table, a group of residents were debating the relative merits of Benidorm and Costa del Sol as holiday destinations, only to arrive at the startling yet prudent consensus that staying here in Canvey Island was best. Eavesdropping on their conversation, and observing the idiosyncratic villas adorned with pigeon lofts and flags, I recognised that an atmosphere of gleeful Island anarchy reigns in Canvey, situated at one remove from mainland Britain.

“The strict conventions of dress and deportment so tiresomely observed in towns can be ignored here in Canvey, and the visitor casts off all artificial restraints, simply observing the ordinary rules of decency and respect towards others which his own courtesy will dictate.”

Crossing through the streets, marvelling at the varieties of bungalows, I came to the Canvey Island Rugby Club playing field at Tewkes Creek, where I sat upon a bench to rest and admire the egrets feeding in the creek, while men walked their bull terriers on the green. Tracing my path back along the wall towards Benfleet station, I discovered circles of field mushrooms and picked myself a bunch of the wild fennel that grows in abundance, imparting its fragrance to the breeze. Then I returned home on the train to Fenchurch St at six, pleasantly weary, sunburnt and windswept, with my mushrooms, plums and fennel in hand as trophies, enraptured by all the delights of Canvey.

“For the family there is no better spot than Canvey for holidays – the glorious, exhilarating air sends them home again pictures of health and happiness.”

I never saw Canvey Island’s petrochemical refineries, or what happens at night. I am prepared to countenance that Canvey has its dark side, but I was innocent of it. I am an unashamed day-tripper.

This boat is for sale, contact the owner at Rapkins Wharf, Canvey Island.

Mushrooms picked at Canvey.

Plums and fennel from Canvey

The wall around Canvey Island.

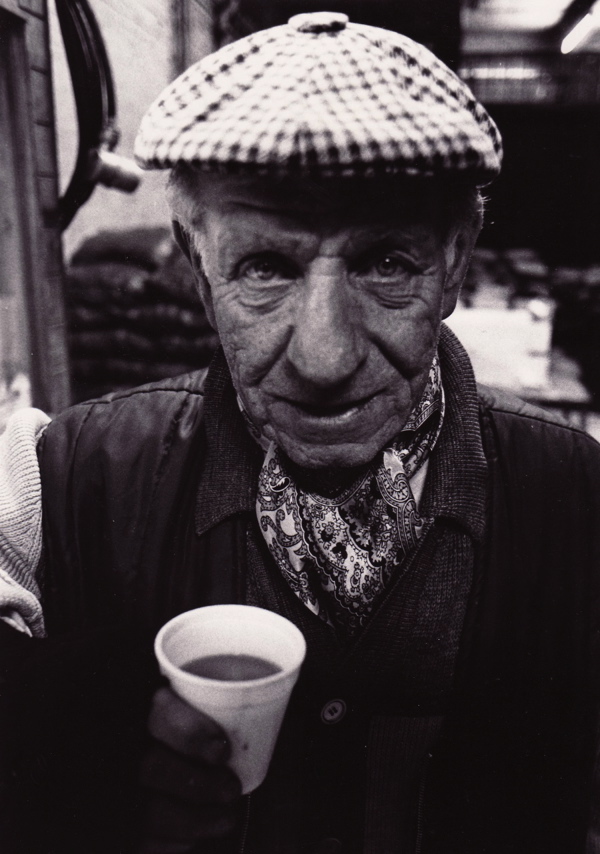

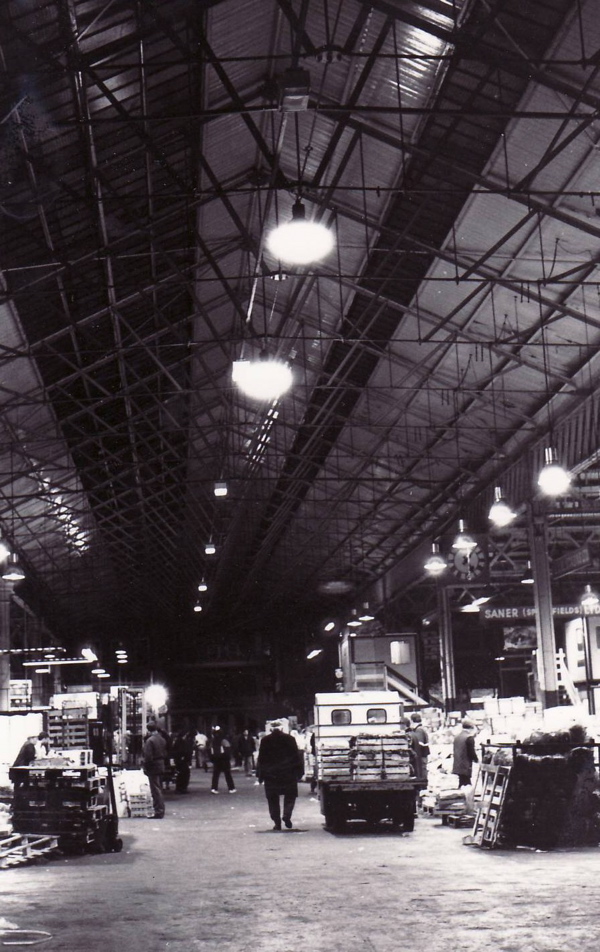

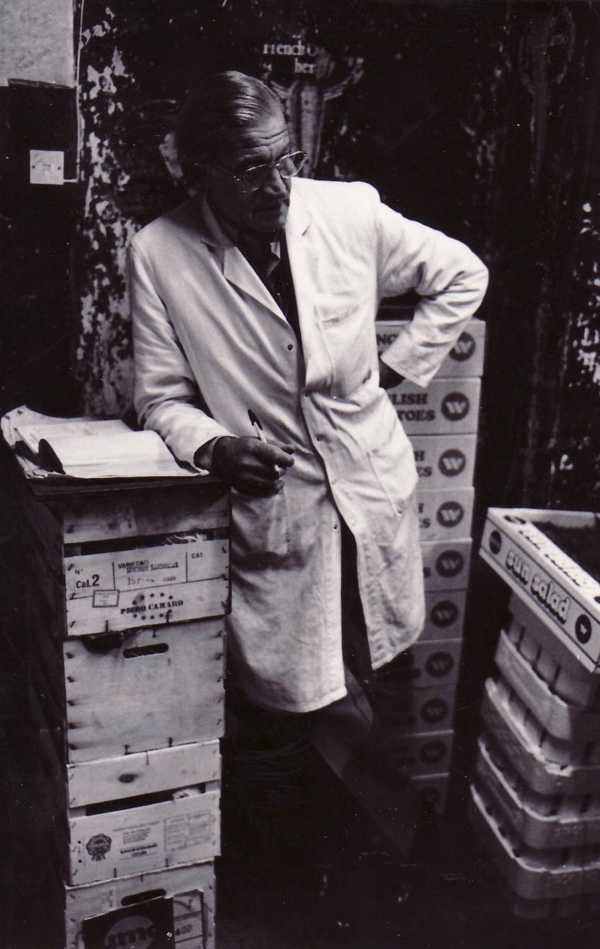

At the New Spitalfields Fruit & Vegetable Market

Last week, twenty years after he photographed the final months of the old fruit & vegetable market, Mark Jackson returned to Spitalfields for the first time. Shortly after completing his year’s photographic project in collaboration with Huw Davies in 1991, Mark took a job in Scotland where he has spent the intervening decades, but at the invitation of Janet Hutchinson of the New Spitalfields Market Tenants’ Association, he was persuaded to return for one night to photograph the fruit & vegetable market as it is now.

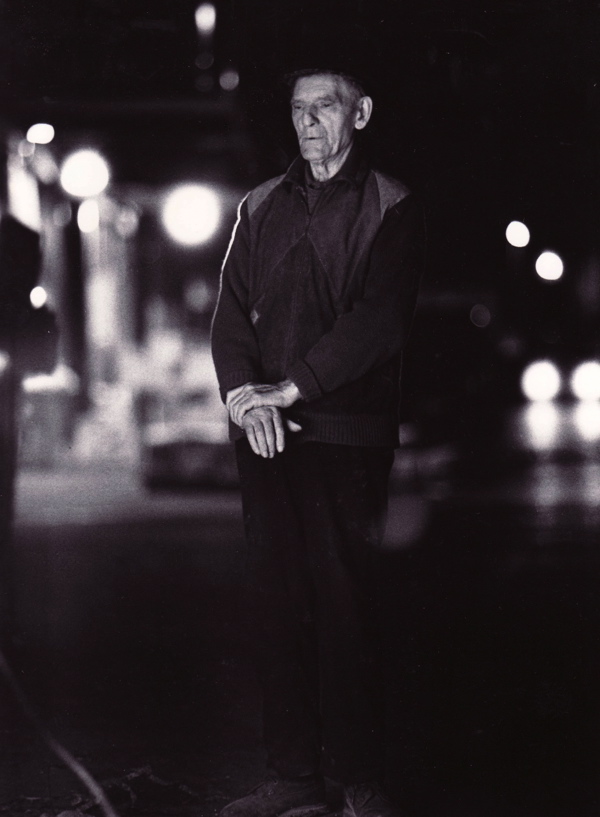

Mark came down from Aberdeen on the train and we met for a late drink at The Golden Heart in Commercial St, before taking a night bus to Hackney Wick and walking East until we came to the New Spitalfields Fruit & Vegetable Market, blazing with light through the darkness and rain. Although the market has been operating in Leyton successfully for nearly twenty years now, it still describes itself as “new.” And for Mark, it was a paradoxical experience, simultaneously familiar and unknown.

“The first aspect to strike me was the size of the new market, even the car park is vast – a stark contrast to the old lorry park at the top of Brushfield Street in E1 – it resembles a giant rave for white vans! Another difference is that the market is closed to the public now, late night revellers used to pour through the old market on their way home in 1990. Today there is a sense of being removed from the centre of London geographically, although not in spirit because the new market retains the same hum of business, the same frantic pace of sell, load and banter.

Over the years my memory has become monochrome. Huw and I worked in black and white and began to think in terms of contrast, shadows and grain, whereas the modern market is dominated by colour. Piles of fruit create an entire spectrum now the market is lighter, powerfully illuminated, and the produce is stacked much higher. Remarkably, some of the wooden carts I photographed still survive, but they are scattered thinly, replaced by a superhighway of forklifts swinging past like muscular daleks with tight turning circles.

The new building reflects the structure of the original with wide avenues and a roof constructed of girders, and a long thin line of overhead lamps. Yet in spite of the modern environment, some of the traders still have the same old desks and the clock on the main avenue was familiar, but I noted that very few of the salesmen wore the long overall that was almost a trademark uniform years ago. Although the languages and accents are more varied today, I recognised quite a few faces from before the move and a couple even remembered me too. Some I recalled working with their fathers when I was last here.

Twenty years ago, I returned frequently to photograph and absorb the spirit of Spitalfields – I revelled in it. By comparison, this was a flying visit and it was harder to soak up the essence in a much shorter time, so I’d welcome the chance to return and take more pictures. But it was very exciting to be ‘back’ and the reception was a really positive.”

When we met at The Golden Heart, Mark had already travelled overnight by train from Scotland and then completed a day of meetings in London, so I wondered how he would find the energy for a night awake at the market. Yet I need not have feared, because once we arrived he set to work tenaciously, excited by the environment, talking with one after another of the many hundreds who work there. If any were too busy, Mark arranged to return later in the night, revealing an enviable ability to strike up a conversation with anyone and everyone, speaking always as equals.

As we walked together, dodging the myriad forklifts flying past at death-defying speeds, I became aware of emotive conversations breaking out between the traders and customers, often in languages I did not understand. Many customers are wholesalers who need to pay the lowest price or risk making no profit at all, while equally the traders also have to make a profit selling the stock they have bought from producers, without losing customers to competition from other traders. This constantly volatile negotiation between the trader and the wholesaler is the point of maximum tension in the supply chain. It can be the cause for jubilation or disappointment, and Mark’s acute pictures of the traders totalling up their figures capture the exact moment of discovering which it will be.

I left Mark to pursue his personal exploration alone and wandered off along the long cathedral-like aisles lined with stacks of brightly coloured fruit under the halogen lights, gawping at the produce and savouring the fragrances of garlic, coriander and all the diverse varieties fresh greens gleaming with raindrops. Cobnuts and chanterelles were reminders of the season on this chilly night at the tail end of Summer. At the end of each aisle, I emerged through the hangar doors into the chaotic dark car parks where boxes were loaded all through the night in the incessant rain.

When dawn broke, we enjoyed a cooked breakfast with Jan Hutchinson at Dino’s Cafe to warm us after our night awake. Just six months into her job as Chief Executive, Jan is a passionate advocate for the market and, appreciative of the vibrant history and culture she inherits, she was eager to welcome the return of Mark Jackson. After so many hours awake, Mark could barely believe that the pictures he took half a lifetime ago had led him there. With the original portfolio of pictures by Mark Jackson & Huw Davies now acquired by the Bishopsgate Institute, I am delighted that their photographic endeavour of twenty years ago to record the life of the market is finally winning the recognition it deserves.

At Spitalfields Market 2010

At Spitalfields Market 1990

Photographs copyright © Mark Jackson

You may like the read my portrait of Jim Heppel, New Spitalfields Market

At the Old Spitalfields Fruit & Vegetable Market

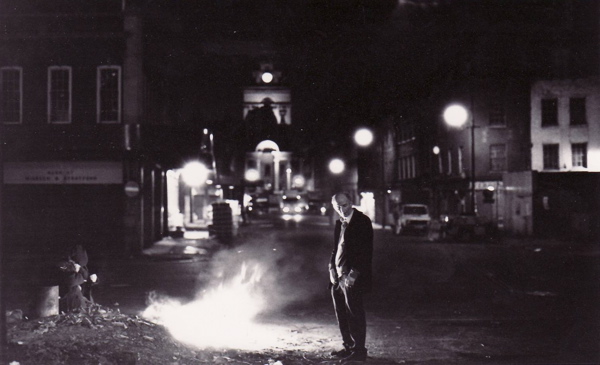

In the last eighteen months of the Fruit & Vegetable Market in Spitalfields, young photographers Mark Jackson & Huw Davies set out to record the life of the market that operated on this site for over three centuries, before it closed forever in 1991. As recent graduates, Mark was working in a restaurant at the time and Huw was a bicycle courier. Without any financial support for their ambitious undertaking, they saved up all their money to buy cameras and rolls of film, converting a corner of their tiny flat into a darkroom.

“It was quite a struggle,” Mark Jackson confided to me, “because we weren’t earning a lot of money. But Spitalfields fired our imaginations. We caught the last tube to Liverpool St and spent the night there taking photographs, before heading into work next morning.”

The result of their passionate labours is a portfolio of more than four thousand images that has recently been acquired by the Bishopsgate Institute, due to be shown there in a major exhibition next year. It is my privilege to be able to show you a small selection of these phenomenal pictures that have never been seen before, as the first glimpse of an undiscovered photographic treasure trove.

I have the greatest respect for anyone who sets out to pursue idealistic projects such as this at great cost to themselves of money, time and labour. In this case, I am equally impressed by the quality of Mark & Huw’s photographs as distinguished social documentary, unsentimental yet infused with affectionate poetry too. Today, we are the fortunate beneficiaries of their selfless enthusiasm over all those months when they stayed up each night to take pictures and worked each day to buy film. It sounds like a beautiful story in retrospect but I have no doubt it took plenty of determination to carry the project through in isolation. I know that the market traders warmed to the young photographers and I think, in part, this accounts for relaxed intimate nature of some of these images, because the traders respected the commitment that Mark & Huw demonstrated, turning up night after night.

This particular set of images take us on a cinematic journey from the busy nocturnal world, when the market was active, through dawn into the early morning when the drama subsided. Mark & Huw photographed a dignified gallery of both the market traders and the homeless people, who were drawn by the fire that always burned to alleviate their discomfort ever since the market was granted its charter. We no longer see any of these characters in Spitalfields. These men would look displaced here in the renovated market today, they are soulful faces from a universe that is gone. When I walk through the Spitalfields Market at night now, it feels like an empty theatre, lacking the performance of the nightly drama that ran from 1638 when Charles I signed the licence to commence trading.

Even though Mark & Huw took their pictures only twenty years ago, they describe a society that feels closer to the world Dickens knew than our own present tense, ten years into the twenty-first century. Inspired by Tom Hopkinson and Bert Hardy’s work at Picture Post, these photographs were to become the first of a series documenting all the markets of London, that might have been a lifetime’s vocation for Mark & Huw. It was not to be. Life intervened and without any support the projected sequence was abandoned. Mark became a writer and Huw is now a teacher – they each have lives beyond their nascent photographic enterprises – but they deserve to be proud of these vital pictures because they are an honourable contribution to the worthy canon of British documentary photography.

Photographs copyright © Mark Jackson & Huw Davies

Simon Pettet's tiles at Dennis Severs' House

Anyone who has ever visited Dennis Severs’ house in Folgate St will recognise this spectacular chimneypiece in the bedroom with its idiosyncratic pediment designed to emulate the facade of Christ Church, Spitalfields. The fireplace itself is lined with an exquisite array of delft tiles which you may have admired, but very few people today know that these tiles were made by craftsman Simon Pettet in 1985, when he was twenty years old and living in the house with Dennis Severs. Simon was a gifted ceramicist who mastered the technique of tile-making with such expertise that he could create new delft tiles in the authentic manner which were almost indistinguishable from those manufactured in the seventeenth century.

In his tiles for this fireplace, Simon made a witty leap of the imagination, using them to create a satirical gallery of familiar Spitalfields personalities from the nineteen eighties. Today his splendid fireplace of tiles exists as a portrait of the neighbourhood at that time, though so discreetly done that unless someone pointed it out to you, it is unlikely you would ever notice amongst all the other beguiling details of Dennis Severs’ house.

Simon Pettet died of Aids in 1993, eight years after completing the fireplace and just before his twenty-eighth birthday, and today his ceramics, especially this fireplace in Dennis Severs’ house, comprise an intriguing and poignant memorial to remind us of a short but extremely productive life. Simon’s death imparts an additional resonance to the humour of his work now, which is touching in the skill he expended to conceal his ingenious achievement. As with so much in these beautiful old buildings, we admire the workmanship without ever knowing the names of the craftsmen who were responsible and Simon aspired to this worthy tradition of anonymous artisans in Spitalfields.

Once Anna Skrine (the former custodian of 27 Fournier St) told me the story, I wanted to go over to Folgate St and take a look for myself. And when I squatted down to peer into the fireplace, I could not help smiling at once to recognise Gilbert & George on the very first tile I saw. Simon had created instantly recognisable likenesses that also recalled Tenniel’s illustrations of Tweedledum & Tweedledee. Most importantly, the spontaneity, colour, texture and sense of line were all exactly as you would expect of a delft tile. Taking my camera and tripod in hand, I spent a couple of happy hours with my head in the fireplace before emerging sooty and triumphant with this selection of photographs of Simon’s tiles for you to enjoy. Reputedly, there is a portrait of Dan Cruickshank, but it must be hidden behind the fire irons because I could not find it that day.

Mick Pedroli and David Milne, manager and curator at Dennis Severs’ house, who graciously permitted me to invade the fireplace for a morning, were part of the social circle connected to the house that included Simon in the nineteen eighties. They talked about Simon affectionately as a vivid and charismatic presence and revealed that Simon’s clothes remain there in his trunk in his room. Let me also admit my gratitude to Martin Lane for whom Simon made a fine fireplace in the delft style for his Elder St dining room in 1988. Martin allowed me to photograph the plaque dating his fireplace, which has the order of service from Simon’s funeral in Christ Church, Spitalfields, tucked behind and concealed within the chimney breast.

A week later, I sat down with Marianna Kennedy (who did the gilding on the fireplace) and Jim Howett (who did some of the carpentry) and we enjoyed an afternoon looking at each of these tiles together, as they deliberated over the identities of the people, before arriving at a consensus, accompanied by colourful stories and engaging digressions about the individuals in question. Finally, Hugo Glendinning and Anna Skine told me about the last year of Simon’s life, when he knew he was dying and moved to 27 Fournier St to be cared for there. Hugo described a candlelit party in the last months of Simon’s life, when hundreds of people came to fill the house and celebrate with Simon. Fifteen years on, everyone in Spitalfields who knew Simon remembers him fondly.

When I had almost finished photographing all the tiles, I noticed one placed at the top right-hand side that was entirely hidden from the viewer by the wooden surround on the front of the fireplace. It was almost completely covered in soot too. David Milne used a kitchen scourer to remove the grime and we discovered this most-discreetly placed tile was a portrait of Simon himself at work making tiles. The modesty of the man was such that only someone who climbed into the fireplace, as I did, would ever find Simon’s own signature tile.

Gilbert & George.

Raphael Samuel, foremost historian of the East End.

Ricardo Cinalli, artist.

Jim Howett, furniture maker, whom Dennis Severs saw as the fly on the wall in Spitalfields.

Ben Langlands & Nikki Bell, two artists who made money on the side as housepainters.

Simon De Courcy Wheeler, photographer.

Julian Humphreys, who renovated his bathroom regularly, “Tomorrow is another day.”

Scotsman, Paul Duncan, who worked for the Spitalfields Trust.

Douglas Blain, director of the Spitalfields Trust, who was devoted to Hawksmoor.

The individuals portrayed in this notorious incident in Folgate St cannot be named for legal reasons.

Keith and Jane Bowler of Wilkes Street.

Her Majesty the Cat, known as “Madge,” watching “Come Dancing.”

Marianna Kennedy and Ian Harper, who were both students at the Slade.

Rodney Archer with his mother Phyllis, of Fournier St

Anna Skrine, secretary of the Spitalfields Trust.

Simon’s discreetly place self-portrait.

The fireplace Simon Pettet made for Martin Lane’s house in Elder St, with the order of service for Simon’s funeral tucked behind.

Simon Pettet, designer and craftsman (1965-93)

The Strippers of Shoreditch

Last night, I met a nice girl called Lara for a drink in The Pride of Spitalfields with her good friend Sarah, a photographer. Superficially, if you were introduced to the fresh-faced Lara Clifton and she flashed her dark eyes and her lovely gap-toothed smile that gives her an appealing aura of gaucheness, you might assume she was once a member of the Brownies or the Pony Club. You would certainly recognise her as a well-brought-up girl. You would never in a million years guess that she enjoyed a successful career as a stripper. You would not believe that it is her in the picture above. But Lara has far more sophistication, intelligence and moral courage than meets the eye upon first introduction.

“My flatmate started doing it,” says Lara, explaining how she began, “And I was shocked until I realised that it was less exploitative and better paid than the office temping I was doing. It was a more honest form of commerce and a lot of the girls enjoyed doing it. It was not sleazy or seedy.”

I was startled to hear this because I perceived stripping as a degrading activity that humiliates women, but this is not Lara’s view. Commenting on the notion of the dominant male gaze, Lara proposes a different perspective, “The punters are like little boys in a sweet shop, it’s a gentle gaze, it’s passive, very respectful. Everyone knows what’s going on. Nothing is hidden.” And Lara speaks warmly of the relationships between the girls too, “There is this genuine camaraderie. You quickly get to know people if you are naked together.” In Lara’s description, it sounds like they enjoyed a high old time, “The girls used to jump from table to table, it was like a crazy circus. They were the best group of people ever.”

Lara is quick to qualify her comments, emphasising that she can only speak for her own experience. And I must applaud her audacity in making such a brave career move because, even if Lara took to stripping like the proverbial duck to water, I have no doubt it took strong nerves to step out naked in public and laudable self-confidence to be open about what she did when there are plenty who would not hesitate to censure. Lara explained the routine to me whereby three women would perform in sequence during an evening, giving three shows each over three hours and passing the jug around before every strip. In Lara’s eyes, it was entirely preferable to the many more hours temping in an office to earn a comparable sum. I was intrigued by Lara’s interpretation of the power relationship between stripper and punter and it was my understanding that a strip ended at the moment of full nudity, but I learnt this not the case in Lara’s world. She ran around the pub naked, performing not on a stage but commanding the whole space, though, significantly, Lara always kept her high heels on, as the symbol of her dominant status within the performance arena over which she held control.

One day, Lara put a note on the changing room wall requesting written contributions from her fellow strippers and quickly found she had enough material for a book. Before long, Lara met photographers Sarah Ainslie and Julie Cook, who visited the pubs and the dressing rooms recording every aspect of the culture in hundreds of arrestingly candid and delicate pictures. “It was a gift,” admitted Sarah,“I drifted in and out for months, so I built a relationship with the girls.” “We forgot she was there,” says Lara, which is quite remarkable considering that in most pubs a single toilet served as makeshift changing room for all the dancers.

Three years in the making, the result is “Baby Oil & Ice – Striptease in East London”, a large format full-colour hardback limited edition book of nearly two hundred pages edited by Lara, that blends writing and photographic imagery together to create a broad and authoritative picture of the particular hidden world of East End striptease. “I wanted to capture something that was dying,” says Lara fondly, but she has achieved far more. Her remarkable book is an exuberant celebration, created by women, of the life, poetry and contradictions of this entirely absurd practice of a woman cavorting naked in clunky high heels for the pleasure of a mesmerised (and paradoxically emasculated) bunch of fully dressed men. Previous books about stripping were written by journalists and academics with their own moral agendas, but Lara’s book is important because it is the first written by performers – allowing the voices of real live strippers, who are usually silent, to speak in their own unedited words.

Until very recently, there were several pubs in Shoreditch that hosted stripping and formed a circuit for the performers, Ye Olde Axe, The Royal Oak, The Spreadeagle, Browns, The Crown & Shuttle and The Norfolk Village. Now this has ceased and some are closed entirely, although Lara says The White Horse still has strippers. Lara gave up when table dancing came in, because it took away the quality of performance from girls who could no long do their acts with their own music, and “I was rubbish at getting money out of people,” admits Lara wryly and somewhat unconvincingly.

You can buy a copy of ”Baby Oil & Ice” direct from Lara Clifton for £25 and she will sign it for you personally. Definitely a collectors’ item. Simply email lclifton76@gmail.com

“I think that your private body and your public body are very different…”

“My pleasure in stripping comes from the eye contact with customers that makes you conspirators. Over the years, I’ve had to learn how to engage this unspoken rapport in subtle ways – in stages that evolve gradually because the norm provides a natural distance from the client, which to my mind has to be breached, psychologically rather than physically. Effectively, the seduction, the tease is in the implied relationship not in the nudity…”

“Stripping was, in a lot of places, less of a spectator sport than it is now. Most places had no stage, which made the dancing environment more intimate, and probably then, inevitably, more interactive. Hands had to be playfully pushed away, baby oil and ice were commonplace props, and once, quite early on I had the misfortune of working with a girl who shot ping pong balls from between her legs into your pint glass!”

Professionally Speaking

I lead a life that millions would Envy, if they understood That it’s possible to flaunt your vanity Whilst holding firmly onto sanity. (Which at times can be tough When you’re parading in the buff And some intellect yells “Show us yer tits!” ‘Cause you want to smash his face to bits.) But instead, you smile once more, As if you never heard that before, You let him you think he’s really funny And then he gives you lots more money Which contributes to your untold bills And also pays for meals and thrills Of going to strange exotic shores, Where everything you want is yours. So for many reasons, I declare it, That I am proud to grin and bear it.

“The job makes you realise how insecure most men are. They put on this front to make them look macho. The more sad and insecure they are, the more they have to hide behind this front. Men are all kids. They’ll never grow up. I’ll never hate men.”

“Whether you are young or old, rich or poor, a gentleman or a complete tosser, the love of beautiful naked girls will have all types of men in the same room. By having alcohol mixed with testosterone, I see a different side of men that most women will never get to see and I definitely know I am a lot less naive for having seen it. I use this information to decide what kind of person I want to be with in my private life.”

Stripper photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Photograph of Ye Olde Axe copyright © Julie Cook