Tony Jack, Truman’s Brewery Chauffeur

“I was born in Balmoral Castle and I grew up in Windsor Castle …” Tony Jack told me proudly without bragging, “… they were both pubs in Canning Town.” It was a suitably auspicious beginning for an East End hero who was barely out of his teens before he joined the RAF and sent this picture home inscribed, “To Mother, Myself in a rear cockpit of a Harvard with the sun in my eyes. Love Tony.” Yet destiny had greater things in store for Tony, he was appointed to secret government work in Princes Risborough, where his sharp young eyes qualified him as an expert in photographic interpretation of aerial surveys, snooping on Jerry. If Tony spotted activity behind enemy lines, the information was relayed to our spies in the field who went to make a reconnaissance.

From there, young Tony was transferred to work in the Cabinet War Rooms deep beneath Whitehall where he barely saw daylight for weeks on end, taking solace in rooms lit with ultraviolet to induce the sensation of sunlight. Tony was involved in developing photographs of the blitz and making maps, but at the culmination of hostilities he was brought the document that ended the war, to photograph it and make fifty copies. With his outstanding eye for detail, Tony noticed that the date had been altered in ink from 7th May to 8th May 1945, and, with the innocent audacity of youth, Tony tentatively asked Winston Churchill if he would prefer this aberration photographically removed. “The Americans wanted the war to end on one date and the Russians wanted it to end on another,” growled the great man to the impertinent young whippersnapper in triumph, “But I got my way, May 8th!” And thus the correction duly remained in place upon the historic document.

When Tony told me these stories as we sat together drinking tea in Dino’s Cafe in Spitalfields this week, I did wonder how he could possibly follow these astounding life experiences when the war ended, but the answer was simple. Tony got a job as a chaffeur driving a Rolls Royce for the Truman Brewery in Brick Lane.

“There were seven of us and we were nicknamed the Black Crows on account of our black uniforms. We used to kick off the day by picking up the directors from railway stations and driving them to the brewery. During the day we used to drive them to and fro visiting pubs and there also was a certain private aspect, which we kept quiet about, taking their wives shopping. Most of the other chauffeurs had once driven delivery trucks for the brewery. They couldn’t tell you the names of the streets but they knew where all the pubs were, that’s how they navigated around London!”

“You couldn’t wish to work in a better environment than a brewery,” admitted Tony in rhapsodic tones, as he opened a worn plastic bag to show us his cherished cap badge and buttons that he keeps to this day. And that was when Michael-George Hemus (who is responsible for bringing Truman’s Beer back to life with his business partner James Morgan) got excited, holding up the rare badge to the light and scrutinizing it in wonder. And then, caught in the emotion of the moment and experiencing a great flood of memories, Tony launched into a spontaneous eulogy about the brewery, which gained an elegaic lustre in the description.

He told me the name of the head brewer was Gun Boat Smith. He told me the brewery had two black London taxis for visiting pubs incognito, registration numbers HYL55353 & 4. He told me there were two chefs in the canteen, one named Harry was a woodcarver who carved fancy work for churches and the other was a glass engraver who could put a painting into a glass and copy it onto the surface. He told me that John Henry Buxton asked “What regiment were you in?” and when Tony revealed he was in the RAF, declared, “Well, never mind!” He told me that a man called Cyclops was responsible for the “finings” which filtered the beer, as well as repairing the bottling girls’ clogs and distributing pints of beer to the delivery men in the mornings. He told me that the phone number of John Henry Buxton’s country home was Ware 2, a source of endless amusement when you asked the operator to connect you. He told me that the brewery staff manned the roof with buckets of water when the great Bishopsgate Goods Yard fire of 1964 sent burning cinders drifting into the sky. He told me that the brewery had its own customs officer because beer was taxed as it was brewed in those days. He told me that there was always a cooper on call night and day to make repairs, in case a barrel of beer split in a pub. He told me that the dray horses sometimes got out at night and wandered around which terrified him because they were magnificent creatures. He told me that there was priest who worked in the electrical shop who would marry employees. He told me that there was a man who was solely responsible for all the uniform badges and buttons, who was TGWU representative and also the Mayor of Bethnal Green. He told me that there was a rifle range below Brick Lane which still exists today and the cleaners refused to go there alone because there were so many rats. He told me that the shire horses were all sent to a retirement home in Long Melford. He told me that the brewery organised Sports Days and Beanos on alternating Summers. He told me that the Sports Days were held at Higham Park, Chingford, where they brought in circus acts to entertain the children. He told me that the Beanos were at Margate. He told me that they hired two trains from Liverpool St to get them there, and a paddle steamer to take them on a trip over to Folkestone and back for a sit down dinner at Dreamland. He told me that there was always plenty of beer on the train coming back. He told me that they were wonderful days out. He told me that Truman’s were unique in the sense that they were self-sufficient, you had no need to go outside.

One day, Tony was candidly given advance notice by the chairman, while driving him the Rolls Royce, that the brewery was being sold to Grand Metropolitan and chauffeurs would no longer be required. So Tony switched to working as a security guard for many years. “I know every inch of the brewery,” he assured me authoritatively. Then in 1969, Tony became a cab driver which he continued to do until 2007. “I retired just before I was eighty. I was happy because I was driving around and it was all I wanted to do in life,” he confided to me with a lightness of tone, revealing endearing modesty and impressive stamina.

All the astonishing details of Tony Jack’s vibrant description of life at the brewery were whirling in my mind as we crossed Commercial St and walked down Brushfield St together in the Autumn sunlight, before shaking hands in Bishopsgate. And then he hopped on a bus to Clerkenwell, where he lives, quite the most sprightly octogenarian I have met. It must be something in the beer.

A studio portrait of Tony from the nineteen twenties.

As a young man Tony acquired the nickname “Thumbs up!”

Tony is in the centre with his head down, working on a photographic interpretation of aerial surveys of enemy territory, as part of secret government programme in Princes Risborough during World War II.

The tax disc of the Rolls Royce that Tony drove for the Truman Brewery in the nineteen fifties.

The eagle on the left was Tony’s cap badge, the THB his lapel badge, along with two sizes of buttons, all from his chauffeur’s uniform. The eagle on the right was a truck driver’s cap badge and the key fob was from an ad campaign, “Ben Truman has more hops!” They are all laid upon a letter dated 29th June 1889, analysing the chemical constituents of the beer, that Tony salvaged from a skip when Truman’s were throwing out their archive. It concludes, “I do not think the beer is at all more laxative than any Burton beer would be in this weather.”

John Henry Buxton invited the members of the Brewery Angling Club to clear the weed out of the river at his estate at Wareside, Hertfordshire, in return for letting them fish in it.

Tony’s membership card for the Truman Brewery Sports Club dated 1st March 1959.

Tony photographed his daughter Janet on the roof after a Christmas party in the nineteen fifties.

Tony’s last day as cab driver in 2007, he drove Janet up to the West End for a shopping trip.

Michael-George Hemus of Truman’s Beer with Tony Jack at Dino’s Cafe, Spitalfields

Tony Jack

New portraits copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Martin Usborne, A Fox in Hoxton

At this time of year, as the shadows get longer and people hurry home through darkened streets, the foxes of the East End grow bolder, reclaiming their territory. Those that have acquired a taste for curry come streaming down Brick Lane in the early hours to pillage the bins, and throughout Spitalfields you may even see foxes during daylight hours skulking in the side streets, as familiar with humans as we have become with them. Consequently, I did not blink when I caught a glance of the first of Martin Usborne’s fascinating fox photographs. My immediate assumption was to admire his skill in capturing a rare moment – until I saw the other pictures and realised that a sly ruse was involved.

Now that digital manipulation of photography has become commonplace, there is an elegant poetry in the plain contrivance of taking a stuffed fox and placing it in the street, because a natural correlation exists between the still life of taxidermy and the frozen moment of a photograph. So familiar are we with photography as a record of an event that we naturally imagine the movement before and after the frame, an impulse that still exists even after we know the fox is immobile.

There is also the delight of complicity here, in observing how different people gamely participated in Martin’s project, when he spent three days wandering around with a dead fox that he rented from “Get Stuffed” taxidermy hire in Islington. (Martin was assured that the fox died of natural causes and was given to the taxidermist by the RSPCA.) The comedy of the undertaking is irresistible, even if it is underscored by the poignancy of this displaced creature returning to its urban habitat after death.

Athough foxes are common in the city, the surrealism of their presence never fails to startle, and these cunning photographs play upon this familiarity, pushing the limit of credibility. Since foxes appear to be as at home in the East End as we humans are, it would not actually be out of character for them to do any of the things shown here. It makes perfect sense to see a fox get cash from a machine and then hit the fried chicken shop. Equally, when I saw the picture of the fox with the girls in the cocktail bar, I could not help wondering if it was a hen night.

In reality, there is a large family of foxes that live in a secret enclave in the Old Truman Brewery, Brick Lane, which makes them perfectly placed to take advantage of the night life on their doorstep. Here in Spitalfields, I have become quite used to seeing foxes gambolling in my back yard. Although guests get excited to see the foxes emerging from the undergrowth seeking chicken bones whenever I serve dinner in the garden, this has become commonplace to me now. Sometimes in the Spring, fox cubs waken me with their cries while playing outside my bedroom window and if I go out at night to bring in washing from the line they prowl around me in the dark. Similarly, the neighbourhood cats appear to have entered into an understanding with the foxes, and I even saw Mr Pussy rubbing noses with a fox this Summer. And I shall never forget returning from the premiere of “Fantastic Mr Fox” to confront a fox on the street in Spitalfields at midnight and half-expecting him to ask, “How was it then?”

So you will understand why Martin Usborne’s clever fox photographs stuck a chord, they are only one step removed from actuality – and their subtle irony renders them as playful and engaging satires upon the absurdity of our curious inner-city existence.

Photographs copyright © Martin Usborne

You may also enjoy Martin’s pictures of Joseph Markovitch of Hoxton.

Martin Usborne’s current exhibition Dogs in Cars is at The Print Space, 74 Kingsland Rd, E2 8DL, until 9th November, Monday to Friday only.

All change at Crescent Trading

In the Spring, I visited Crescent Trading, the last cloth warehouse in Spitalfields, still operating in a way that Charles Dickens would recognise from his visit to a silk warehouse in 1851. Distinguished proprietors Philip Pittack and Martin White are clearance cloth merchants of the old school who have spent their entire lives in the industry, with more than one hundred and twenty years experience between them. For the past twenty years they traded from a charismatic old stable block in Quaker St, but now that the landlord has acquired planning permission to convert the building into a hotel, they are moving to an industrial unit across the road. These are momentous days for Crescent Trading, so I took my camera along to record the move.

I gasped to see the old warehouse, once packed to the rafters now cleared of cloth, and discovered Martin there, a dignified figure, ruminating like Hamlet in an empty theatre. Meanwhile Philip hauled a trolley piled with of bolts of cloth across the street outside, pink in the face with exertion and yet full of cheery resolve to make it to the new premises, where they have taken out a five year lease. “He’s seventy-nine and I am sixty-seven,” confessed Philip as he ran up a ladder with a roll of fabric over his shoulder, demonstrating the careless abandon of a thirteen-year-old, “When the lease finishes he will be eighty-four and I will be seventy-two.” At just two thousand square feet, the new warehouse, constructed of breezeblocks with a metal shuttered door, is half the size of the old one, so Philip has invested in a racking system which means he can stack the cloth higher, but requires him to climb more ladders.

Not many men at his time of life would take on this challenge, yet with heroic enthusiasm, Philip has embraced the whole process of hauling every one of all the thousands of rolls of cloth across the road manually and installing them in the racks, then taking them down and rearranging them to achieve a satisfactory arrangement. As Martin White declared later, deliberately and without overstatement, “Philip’s done a job which is a mighty one and it is quite incredible how it’s been done.”

Already customers are crossing the road, and they seem to like the new arrangement where everything can be seen at a glance. Crescent Trading is a treasure trove for small designers and design students who can buy cut lengths they could not get anywhere else, discovering rare high quality fabrics at a fraction of the cost they would pay at a mill. Even as Philip and I were talking, Mr Amecci, a designer in a snazzy deep blue serge trench coat with fur collar, fedora and forties moustache interposed. “Don’t write this up,” he begged me with winsome irony, “because I don’t want everyone to know! What I like about this place is that I can get things I wouldn’t get elsewhere, like mohair, mohair mixes and chinchilla at discount prices.” Then Matsuri, another cool-cat designer, entered in a Guy Fawkes hat with waist-length locks straggling out beneath, and eager for blazer-striped fabric. Regretfully, Philip had to send him back across the road to the old warehouse for it.

Simultaneously excited by the custom and frustrated by the circumstance, “We’ve come to the point of no return where we are running back and forth across the road!” Philip admitted to me, rolling his eyes and waving his hands in self-dramatizing resignation. Yet within a month, the move will be complete and so I persuaded Philip to take me on a sentimental tour, visiting the first floor storage space that once had a lift shaft big enough to bring shire horses up to be stabled. We passed a huge reptilian conveyor belt for bringing rolls of cloth upstairs – broken ten years ago, it will never run again – and we entered the vast empty warehouse, breathtaking in its lyrical state of dereliction, and possessing a poetry that no industrial unit can ever match.

These are emotional times at Crescent Trading. “I’m petrified,” admitted Philip when we were in private, revealing the nature of the passion that has driven him to manhandle every roll of cloth across the road, “We were happy. We had our feet under a table for twenty years. Now we eek out a living and times are very difficult. We have to work because all our money is sitting on the floor. This street used to be all small businesses, a trousermaker, three printers, a quilter and a dressmaker. I am angry that the council zoned this street as small businesses, and now it’s going to be just a hotel and a housing block.” And then, concerned that he might have lowered my spirits with this outburst, he put his hand into a box and slipped a bottle of whisky into my bag as I walked out the door.

Let me reveal, my sympathies are with Philip Pittack and Martin White for many reasons, not just because of the whisky, or because they carry the history of the textile industry in Spitalfields with them, but most importantly because they are two of the most soulful and witty gentlemen you could ever hope to meet. They are my heroes, wielding scissors and tape measures. Legends in the rag trade, they know as much as anyone could ever know about cloth and they love meeting all the young fashion students that come seeking inspiration. Whenever you visit Crescent Trading you will discover joy, because they sell it by the yard. Nobody is making a fortune, but everyone takes delight in celebrating all the varieties of fabric and the glorious multifarious human culture that attends it.

Thanks to sheer willpower, canny ingenuity and a superhuman expense of physical energy on Philip Pittack’s part, Crescent Trading is still here. Everything has changed yet nothing has changed.

Philip Pittack takes a last look at the warehouse where he stored his cloth for twenty years.

Philip sits upon the conveyor belt that broke ten years ago.

Philip personally manhandled every roll of fabric across Quaker St to the new warehouse.

Martin White contemplates the old premises, soon to be a hotel.

Philip arrives at the new warehouse on the other side of Quaker St.

The old warehouse.

The Stripper & the Oral Historian Chit Chat

These pictures illustrate what happens when you put a stripper and an eminent oral historian together in a photobooth. It was the perfect way to record the outcome of the our first Chit-Chat presented last week at Rough Trade East, with Lara Clifton celebrated stripper of Shoreditch in conversation with Clive Murphy, oral historian of Spitalfields and writer of ribald rhymes. For those of you who were not able to be there, here are a few excerpts to give you a flavour of the occasion.

Clive: When I was told I was going to interview a stripper, I was very amazed and very honoured, and I was told there was a photo of you and it’s the most outrageous photo I have ever seen in my life! Are you an exhibitionist by nature?

Lara: I guess I must be.

Clive: Because of lot of people do this (I’ve been to Raymond Revuebar and so on) because they are very shy. It’s very, very strange, they overcome their shyness by stripping

Lara: I completely associate with that, I’m a very shy person.

Clive: Would you like to tell me your first professional performance?

Lara: My very first job was at the Nag’s Head on Whitechapel High St and there was a certain circuit of pubs that we did. It used to be that you were paid to be there (given money to cover your travel), but when I was there it got worse, you were only paid the money that was in your pot – though you didn’t actually have to pay to be there like you do now.

Clive: I’ve read that you had a different way of performing to most strippers…

Lara: I used to jump off the stage with my knickers round my ankles and then run through the crowd because it was funny. Everyone came off the stage and jumped from table to table, but I was maybe a bit more hysterical in my delivery – it made the other girls laugh.

Clive: What do you think of the feminist point of view, that you’re demeaning yourself and you’re opening yourself up to men who will despise you?

Lara: I think it’s wrong. They haven’t been in a strip club if they think that’s the way, there isn’t any victimisation going on there, aside from men being asked to put money in the pot. I think it’s a very fair exchange.

Clive: How do you deal with the hostile punters?

Lara: It’s part of the job that you deal with customers and if anyone’s really awful they get kicked out. You get less verbal abuse from men in a strip club than you would in any other pub on a Friday night. Really the only way to offend a stripper is to not give her a pound in the jug.

Clive: You said the clubs were dying out in this area?

Lara: Yes, they are closing them down right now in Hackney and all of the strippers are campaigning against it, but their word is not valid apparently.

Clive: The White Horse is one that I go into …

Lara: That’s one that is in danger.

Clive: …and I just see people doing the crossword in there.

Lara: Yes, it’s genteel of an afternoon.

Clive: Did you dance entirely nude?

Lara: Yes.

Clive: That was ahead of its time wasn’t it?

Lara: No, no, it has been going on a long time in the East End.

Clive: And did you allow people to touch you?

Lara: No, that’s why it was fun because they knew they weren’t allowed, so you could charge at them and they would all run away because they knew they weren’t allowed to touch.

Clive: I thought that was the whole fun of it, trying to touch you.

Lara: Those were different clubs. It used to be even that if anyone had a camera you stilettoed it.

Clive: I knew you were physical! I have done a lot of interviewing but not of sex bombs. Shall we be natural now and every question I ask, you take off one item of clothing?

Lara: I will if you will.

Clive: You’ve called my bluff! So you don’t hate men, humiliating them by making them drool?

Lara: No. Lots of punters become good friends. You rely on regulars, because it’s more or less the same crowd of people that you see every day in all the pubs.

Clive: They become addicted?

Lara: It’s like trainspotting but more fun!

Clive: Did you go into it for money? Did you find it paid so much better than a humdrum job from nine to five, that you preferred it for that reason above all others?

Lara: Not above, but everyone works for money, so you might as well do something you like.

Clive: So you do enjoy stripping?

Lara: Mmm.

Clive: Is there anything else you want to say?

Lara: Let me ask you about oral history, why did you chose to come and live in Spitalfields and talk to people?

Clive: Because I am very interested in people, their background and why they are where are they now. I had done interviews in Pimlico but then I came to live here because a room was vacant at four pounds a month.

Lara: Yowsa! What people did you interview?

Clive: Lavatory attendants, two of them, a male and female and they were both published and I was asked would I do a hermaphroditic one next – but I think they had their tongue in their cheek a bit! I came here and I did an East End Hosteller and a Singer.

Lara: So my book is similar? It’s an oral history of strippers

Clive: Yes, but I did a whole book about each person.

Lara: Amazing!

Questions from the audience.

Question: What’s the situation with Hackney Council trying to close down the clubs?

Lara: All the strippers are writing in and saying this shouldn’t happen. Yet it looks like its going to happen anyway, even those places that have been here a very long time, even before the rich people started moving in. It’s part of this area’s heritage and history, and if we lose the strip clubs not only will a whole body of women lose their income but it’s a vibrant part of what the East End has always been. I think it would go underground, but the pubs manage the laws, so once it goes underground you loose all the rules and it becomes a lot more dangerous for the women.

Question: Do you think social mores with regard to stripping are changing?

Lara: I think people are getting a lot more prudey. The right wing and feminists are almost on the same line at the moment and that I find odd. I can understand how it’s evolved that way but I think there’s a fundamentalism around sexuality which is growing.

Question: Could it be due to the Islamic community?

Lara: But Muslims love strip clubs! Of course they come, everyone comes. One of the most amazing things about going in a strip club is the different people that are in there, the different classes and the different races. There isn’t one type of man that comes to a strip club, you get a variety of different types of men. I did a strip at a Muslim club on Green Lanes. There are also female Muslim strippers who work mostly on the underground scene. They say if their families found out they would be in trouble, but they are doing it because they enjoy doing it and they want to do it, not because they have to.

Question: Can you tell me about the history of stripping in the East End?

Lara: The strippers that I know now in their fifties were working as go-go dancers in the sixties, but there’s also evidence of Victorian strippers who stripped on metal trays with a candle nearby that would show their reflection, but I think they just stripped under their skirts. There’s a painting in Sir John Soane’s Museum that shows a girl holding a tray and that’s what she’s about to do.

Clive: I’ve got a marvellous idea, what about people arriving naked and then dressing slowly – they bring a costume in a bag and then as the evening goes on everyone gets dressed.

Lara: Sounds good! When shall we do that?

Columbia Road Market 56

The full moon was still reflecting in the puddles from last night’s downpour as I walked up to Columbia Rd before dawn to speak with young Albert Dean, at his double pitch selling cut flowers at the Western end of the market. With his knitted hat pulled down over his ears, hopping from foot to foot and rubbing his hands together enthusiastically in the cold, this wiry young man with sharp eyes informed me proudly that, although he has only been working there full time for about five years, the stall has been in his family for four generations.

Albert Dean is the fourth Albert Dean since his great-grandfather to run the pitch on this site – as long as the market has been here – which means that at any time during the last century you could have come and bought flowers from an Albert Dean at this street corner. The current Albert Dean has been working on the stall regularly since he was seven and now that his father is in semi-retirement, his energy motors the business into the future. “I don’t see why not, I’d like to think so!” he declared with an eager grin, when I asked if he expects to be here his whole life. “It’s in the blood, I don’t know anything different,” he announced with a hint of absurdity at his rare horticultural pedigree.

Rising at three in the morning, Albert drives down to Columbia Rd with a lorry full of flowers each Sunday, setting up at five-thirty and returning home again with an empty lorry. Taking Monday off, Albert works for the wholesale side of the business based at Golfside in Cheshunt the rest of the week. Flower orders are sent off on Tuesday, for the coming weekend at Columbia Rd and all the wholesale customers, while Wednesday is Albert’s second day off in his curiously syncopated routine. Then on Thursday, Friday and Saturday, Albert is sending out deliveries to restaurants, corporate clients and freelance florists, as well as preparing for Sunday too, including supplying other stalls in Columbia Rd. “We’re about as cheap as you can get,” he assured me with a toothy grin.

And thus the business has rolled on through four generations. Albert already has a daughter of sixteen months, Taylor May, but if a boy comes along there will be no question but that he will become Albert Deane V. Albert is qualified in his hopes that his children can continue the business, “I’d like to think so, though it’s getting a lot harder with the supermarkets getting better at selling flowers.” he confided cautiously. Yet Albert has the necessary optimistic temperament, acquired over these generations, that requires a energetic focus upon the business in hand, telling me that he actually prefers the cold to the heat. “It’s an incentive to keep moving!” he declared brightly, fidgeting in anticipation of all the day’s activities to come, “And it’s harder to keep the flowers looking good in the heat.”

With Halloween approaching, Albert has Chinese Lanterns (Physalis) on sale alongside a fine variety of decorative foliage. “That’s what all the restaurants are ordering this week!” he confirmed with all the inborn swagger and breezy confidence befitting the fourth generation Albert Dean, standing on the street corner that is his birthright.

Photograph copyright © Jeremy Freedman

In Bishopsgate, 1838

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

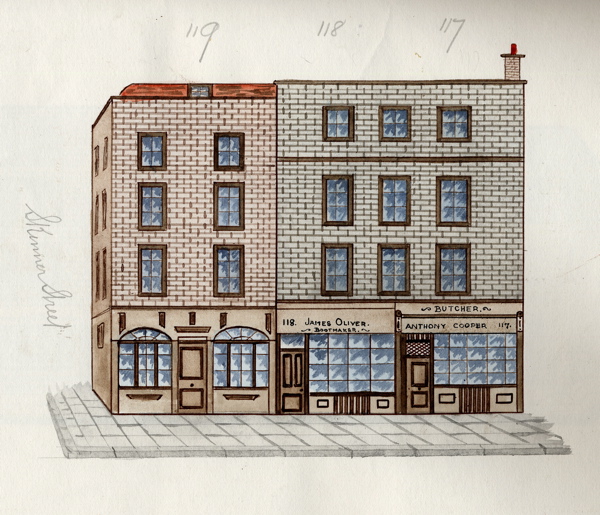

Before anyone ever dreamed of Google’s Street Views, there were Tallis’s London Street Views of the eighteen thirties, “to assist strangers visiting the Metropolis through all its mazes without a guide.” John Tallis created the precedent for a map which included pictures of all the buildings as a visual aid, commissioning the unfortunately named artist Charles Bigot to do the drawings and writer William Gaspey to create the accompanying text. Tallis had his imitators, evidenced by this beautiful set of anonymous watercolours of every single facade in Bishopsgate, Spitalfields, dated to 1838 and preserved in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute.

There is an infantile obsessive quality to these extraordinary paintings that drew my attention when I first came upon them, the degree of control and attention to detail in creating such perfect representations of the world is awe-inspiring. While there is a touching amateurism to the quality of the brushwork and lettering that recalls folk or outsider art, I cannot deny the attraction of the desire to record every facet of the world – because there is a strange reassurance to be gained from looking at these weird yet neat little pictures. They remind me of the idealised visualisations created for buildings that are yet to be built, in which the less salubrious elements, not just the dog mess and litter but sometimes even the people, are excluded in images designed to endear us to the visionary proposals of architects and planners.

Although these views of Bishopsgate advertise their veracity by recording every single brick, I cannot believe it actually looked like this because the buildings are uniformly clean and well maintained, lacking any wear and tear. You cannot imagine John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondia of 1817 walking down Bishopsgate as it is portrayed in these immaculate representations. In contrast to the distorted chaotic nature of Google Street Views that record our contemporary cityscapes, there is a comic flatness in these drawings that are more reminiscent of street scenes in toy theatres and the houses you find on model railway layouts, tempting me to paste them onto matchboxes and create my own personal Bishopsgate. They are innocent of all the complex poetry and patina of Alan Dein’s East End Shopfronts of 1989. Neat, tidy and eminently respectable, the early nineteenth century society envisioned by these innocuous facades is that of Adam Smith’s “nation of shopkeepers,” family businesses like that of Timothy Marr, the linen draper who opened up half a mile away upon the Ratcliffe Highway in 18o8 and came to such a terrible end in 1811.

Yet although Bishopsgate itself is unrecognisably altered from the time of these drawings, the proportion of the buildings, providing a shop on the ground floor, with family accommodation and sometimes workshops above, is still familiar in Spitalfields today. And the two stocks of brick used, red brick and the London yellow brick remain the predominant colours over one hundred and fifty years later. Sir Paul Pindar’s House, illustrated in the penultimate plate, is the lone survivor from the time before the fire of London when Spitalfields was a suburb where aristocrats had their country residences, including Elizabeth and Essex who once had houses on Petticoat Lane. Today the frontage of Sir Paul Pindar’s House can be viewed at the Victoria & Albert Museum where it was moved in 1890.

Named Ermine St by the Romans, for centuries Bishopsgate was the major approach to the City of London from the North leading straight down to London Bridge, and the Saddler & Harness Makers and Coach Builders present in the street reflect the nature of this location as a point of arrival and departure. There are some age-old trades recorded in these pictures that survived in Spitalfields until recent times, Upholsters, Umbrella Makers and Leatherworkers, while the Straw Hat Makers, Cutlers, Dyers, Tallow Sellers and Corn Dealers went long ago. Yet we still have plenty of Hair Dressers today, though I feel the lack of a Fishmonger and a Butcher sorely. Let me admit, my favourite business here is Mr Waterworth, the Plumber. He could become a credible addition to a set of Happy Families, along with all his little squirts.

You can see the frontage of Sir Paul Pindar’s House today at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Images copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

Hosten Garraway, Verger of Spitalfields

Hosten Garraway, Verger of Christ Church is a well known and widely respected figure in Spitalfields. With a natural gravitas and a warm sympathetic nature, you will find Hosten busy most days around Nicholas Hawksmoor’s magnificent eighteenth century church, the building that has been his charge for many years now. It was Hosten who had the job of reopening the church when it had been shut, over twenty years ago, and he has stayed around through all the restoration and building work to become the esteemed custodian who knows it better than anyone today. One quiet morning recently, Hosten and I sat down together in the deserted church, in a pool of Autumn sunlight, and he told me the story of how he came to be here in Spitalfields as Verger. It is a journey that began far away.

“I left Carriacou, an island off Grenada in the Caribbean, when I was eighteen. My mother came to England first and for a couple of years I lived with my uncle who had a small farm, until she sent for me. One day he said to me, “Would you like to go to England?” And straightaway I said, “Yes!” but I remember my uncle was quite concerned for me. We were travelling by boat, not planes then, and there were other lads on the boat that I knew, some who were coming to study, and we stopped off at other islands along the way to pick up passengers. I came from a family that had sailing boats, schooners, so I had sailed with my uncles, but many people became seasick. I went round getting cups of tea for them until a passenger told me to get him a cup of tea – he thought it was my job – so I had to explain that I was not being paid to do it. The voyage was exciting, I felt were all travelling to the same destination even if our goals were not the same. It was a beautiful trip, in which I saw schools of dolphins for the first time, they were racing the boat.

We landed at Southampton and when I got to Waterloo, there was my mother and a few of her friends and relatives to greet me. I think I must have slept for two days, I was so exhausted. We stayed in Old Montague St, Spitalfields, in one of the houses there, on the very top floor. (They were similar to the houses in Fournier St) It gave you a wonderful view of the rooftops. That was September 1962.

I quickly made friends with others in the neighbourhood, some were Irish, Scots, Welsh and some from other islands of the Caribbean, mostly from Jamaica. It was a closely-knit community with all the different peoples. I made friends with a Jewish family who had a shop, and as the years went by I used to help Sam in his little corner grocer shop in Old Montague St.

Sometimes Sam and I would drive down to Kent to deliver supplies to farms in remote areas. And on one occasion, Sam said, “Can you deliver the goods and collect the money?” and I said “OK.” There was a little child aged six or thereabouts with a basket, and I gave her the eggs and bread, but she did not give me the money so I followed her into the farm to get it. The farmer came out and said, “You don’t have to come in here! Who are you?” I explained that I was delivering the order and collecting the money. He said, “I’m not sure I would want you to come back here again.”

Looking at it now, I’m not sure if it was because I followed his daughter, or the idea of a total stranger on his property, or if it may have been the very first time he came into contact with a non-white person, so he may have been surprised. I don’t know. Sam went and explained the situation to the farmer. I don’t know how many years Sam had been delivering to him, but he wasn’t sure the farmer would want him to deliver goods again. “Next time we come, I’ll let you stay in the van,” said Sam. “That’s wise,” I thought.

Being a Jew, Sam asked me to come to his house and meet his wife and son every weekend. Around six o’clock, he would ask me to switch the light on and light the fire, so I thought, “OK, we’re friends.” But Sam hadn’t explained it to his neighbours who were suspicious when they saw me with a key, “Who are you? What are you doing?” they asked, and I explained, “I’ve come to light the fire.” So this went on quite a while, switching the light on and lighting the fire every Saturday. So eventually, I asked Sam, “Why can’t you switch the light on yourself?” and it was then he explained to me a little bit about Jewish culture and the Sabbath. I thought about it afterwards, “Did we become friends because he needed someone to light the fire?” but I think it was more that he asked me to light the fire because we became friends.

I used to go to Evening Classes in the Hanbury Hall, in the days when Christ Church Spitalfields was out of use. Eddy Stride was the Rector then and I started going to Sunday Service and we got talking from time to time and I got married and had two sons and I asked if he would christen them and he said, “Yes.” I was working as a Class A Welder at the time, but then in 1988 I had an accident whereby I was off work for a couple of years. I still attended church regularly and I began visiting some of the people who were not at church that week, as I was not working. Some people thought it was odd because I never chose whose door I would knock on, and the people who attended Christ Church were of mixed background, among those who were more affluent were those thought it “most strange.” I could tell by the looks on their faces. But I still visited and the news got back to Eddy. So he said to me one day, “I hear you have been visiting people, so I’ll give you a list of people to visit.” It took me up to Bethnal Green and as far as Stepney Green.

Then one day, the builders were doing work in Christ Church and a couple of the parish workers asked, “Can we open the church?” But they had no-one to open it, so I volunteered and Eddy Stride took me on one side and said “How would you like to work for the church?” and that frightened me a bit. He said, “You’ll be able to do the same things, but you’ll have to be more reliable. I want you to turn up for prayers on Monday at eight o’clock. You’ll be opening the church for months to come.” I felt nervous, but then he said, “You can talk to people who come into the church,” and then I became even more nervous. I thought, “What can I say to them?” Then I realised, “I’ll give them a tour of the building.” I’d seen Dan Cruickshank talk and seen how he speaks with hands, so he inspired me, and that’s how I got involved with Christ Church. It was very sad when Eddy retired. I used to think, “How will the church tick over in his absence?” but then it worked out quite well. A lay reader named Hugh Shelburn was here for a while. Part of his encouragement to me was to give this advice, “Thank God, look people in the eye, and just love them.”

With these words Hosten completed his story and looked at me. Raising his benign yet unsentimental gaze to meet mine, he humbled me with his plain testimony of a magnanimous soul who has retained an openness of nature – reconciling himself to all the varied experiences of humanity that he has encountered between Carriacou and Spitalfields. From the first incident on the boat, when Hosten described serving cups of tea to seasick passengers, it was apparent to me that he is an independent thinker who possesses a personal moral sense and a strength of character that will not be discouraged. Hosten is a slightly built man and yet he demonstrates an undeniable stature. There is a remarkable quality of stillness in Christ Church, Spitalfields when it is empty of crowds, and Hosten is at peace there in his spiritual home.