John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder of the Tower of London

Spitalfields is one of the hamlets in the vicinity of the Tower of London that today make up the Borough of Tower Hamlets and consequently all residents of the Borough enjoy a special relationship with the Tower which means we can gain entry for just one pound, simply by showing a library card. As a result, it is a place that I delight to visit throughout the seasons of the year and each time I discover more wonders. On a recent bright Winter’s day of frost and sunlight I took a walk from Spitalfields down to the Tower, where I found golden leaves scattered across the old yards surrounding the mythic White Tower, gleaming in the light. When William the Conquerer built this citadel nearly a thousand years ago in 1068, there was little else here and while the modern city has grown around it, the White Tower remains almost unchanged.

The purpose of my visit was to meet the Chief Yeoman Warder and it was an adventure in itself to be escorted into the inner sanctum of John Keohane’s office overlooking the White Tower, where he sat behind a desk, distinguished in his scarlet and black uniform beneath a portrait of the Queen. John has the quiet eyes of an old soldier, reflecting his long record of military service since 1964, when he signed up for a career that took him to Singapore, Thailand, Oman, the Falkland Islands, Belgium, Germany and Northern Ireland, resulting in a whole string of medals. Though for the sake of levity – in case I should be too overawed by his loftiness – John brought out an iphone from a special pocket in his uniform to show me a picture of him in costume as the Fat Controller on the South Devon steam railway, where he enjoys his month’s holiday each year.

In 1485, when Henry Tudor defeated Richard III at Bosworth Field, he brought his personal bodyguard back to his residence at the Tower and appointed them Yeoman Warders. “The privilege is that the appointment is for life,” explained John Keohane who continues this unbroken line of Chief Warders spanning five centuries,“though at New Year we have a toast, ‘May you never die a Yeoman Warder!'” The toast dates from the period before 1826, when the position, which includes accommodation in the Tower, was purchased, thus creating an imperative for the warder to sell out while they were still alive so that their wives would have a pension fund, because you could not sell the position once you were dead.

“In Northern Ireland, I served at the height of the troubles, and you were restricted where you could go. You had to be careful.”, John confided to me, with a glance to the window. And I understood that when you have spent your life living in barracks, as he has done, then it is a sympathetic transition to move into the Tower of London, an edifice which contains a veritable city within the City. To be eligible to apply, you must have a minimum of twenty-two years service in the armed forces and a record of good conduct, a fact which John was quick to qualify as being not so much about the lack of misbehaviour as the lack of being caught. Year in, year out, John lives and works here with his fellow Beefeaters and their families, pursuing an existence circumscribed by duty and ritual. Even the guard rota follows a time-honoured pattern referred to as the “daily waite.” “It doesn’t mean you can’t go out, but you have to follow the rules. People in civilian life would not be satisfied with it.” admitted John, who has made his home inside these walls since 1991.

He explained to me that, until 1603, the Tower was a royal residence and his predecessors ate at the King’s table. In those days cattle were primarily used for milking and their meat was a luxury food, although beef was served to the King and, by tradition, the Yeoman Warders were entitled to what was left – giving birth to the nickname ‘Beefeater,’ the term by which they are most commonly known today. It was the creation of Beefeater London Gin in 1871 which took this name to world with such success that the Yeoman Warders now accept they will always be Beefeaters in the popular imagination.

“You can get photographed as many as four hundred times in one day. Some of the warders take detours walking outside between the offices and their homes because otherwise you can be photographed five or six times just crossing the yard,” John revealed, rolling his eyes at the absurdity of it. Yet as we left the building, he was entirely magnanimous to the visitors who wanted to be photographed beside him. Then as we walked on beneath the White Tower, looming overhead, John cast his eyes around in pleasure at the spectacle and said, “What a place to bring your children and grandchildren to! That’s what sold the job to me. I hated history at school but now I am passionate about it – because this is where it happened.”

He took me into the Tower of London Club, the private bar lined with hundreds of tributes from all the regiments in which the warders have served, and it was a sober image to manifest the integral connection between the Yeoman Warders and the armed services. Then on another wall I came across evidence of a different kind of recognition, pictures of the Yeoman Warders with celebrities including Johnny Depp, Bruce Willis, Jackie Chan, Barack Obama (John showed Michelle and the girls around), Matt Damon, Bruce Forsyth, Sylvester Stallone, and Paul McCartney. These pictures raised the question of who was being photographed with who. The celebrity with the Beefeater? Or the Beefeater with the celebrity? It does seem Yeoman Warders like being photographed with colourful characters, just like rest of us. There is an undeniable poetry to this notion of senior soldiers having a new life in the Tower of London, sedate yet basking in adulation of the two and half million visitors each year. Secluded in their cloistered existence but leaving the confines to accompany the Queen at state occasions – existing at the very centre of their own particular world.

John says the years pass quickly here. Every night at ten precisely, he supervises the Ceremony of the Keys at which the Tower is locked for the night. Twice a year is the Ceremony of the Constable’s Dues when a visiting Naval ship’s Captain reports to the Tower to pay a due to the Constable of the Tower. Annually in May is the Lillies & Roses Ceremony commemorating Henry VI, the founder of Eton College and Kings College Cambridge, who was murdered at the Tower of London in 1471. Every three years is the Beating of the Bounds Ceremony on Ascension Day when the Yeoman Warders visit all the boundary markers in a circle around the Tower to beat them with willow wands. And every five years a new Constable of the Tower is installed as the monarch’s representative at the Tower.

Aware that his twenty years dwelling among these ancient walls is a mere blink in their nine hundred year history, time runs smoothly for John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warden of Her Majesty’s Royal Palace of the Tower of London.

John Keohane points out the figure of the Sultan of Oman in this painting of the state visit to the Tower, of special significance to John because he served in Oman in the seventies.

John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warden of Her Majesty’s Royal Palace of the Tower of London

Photographs copyright © Martin Usborne

On the Papercut Express with Rob Ryan

On Friday, I was thrilled to board a fast train at Euston with Rob Ryan, the papercut supremo, racing North through the dusk to Stafford for the opening of his latest exhibition. “Your job is to take this world apart and put it back together… but even better,” at the Shire Hall Gallery in the Market Square in Stafford, follows just two weeks after the breathtaking sellout success of Rob’s show at the Air Gallery in Dover St, entitled “The stars shine all day too.” He certainly has a way with titles.

While the London exhibition comprised monochrome papercuts and prints – some of truly astounding size and ambition – this show in Stafford features the papercuts he made as illustrations to complement the text by Carol Ann Duffy for “The Gift,” as well as some remarkable ceramics that signal a new departure for him. The gallery in Stafford sourced nineteenth century moulds for Staffordshire figures and they have cast new ones for Rob to decorate. When I visited Rob at his show at Somerset House in the Summer, there was a Staffordshire china dog that he had already decorated sitting upon his desk. By adding a pair of glasses, Rob had drawn attention to the unlikely resemblance between himself with his luxuriant locks and the spaniel with its curly ears. We used to have a pair upon the sill at the top of the staircase when I was child, so I was fascinated by Rob’s hilariously extrovert reworking of these inscrutable figures. And for months now I have been looking forward to seeing these new works, at their first public showing here in Stafford.

After dozing on the train up, we walked through the dark and frosty Friday-night streets of Stafford, and into the tall bright spaces of the Shire Hall where the rich colours of Rob’s papercuts and prints glowed with exuberant life. I went straight to the cabinet of shelves filled by pairs of china dogs and cats, all staring back at me through the glass. There was an exciting tension between the poise of their nineteenth century form and the lively decorative sensibility of Rob’s designs, animating the figures with idiosyncratic personality. It was the perfect marriage of two disparate threads of folk art, the Staffordshire figure and the papercut, both reinvented by Rob Ryan in an entirely contemporary way. The words which Rob applied exemplify the thoughts I always imagined the dogs on my parents’ staircase harboured. Naturally meditative and sometimes contradictory, reflecting the fact that these creatures are mirror images of each other, the texts are secret insights into the collective psyche of china dogs and cats. Now we know what they were thinking all along.

I was interrupted from my reverie by a local councillor giving a speech. He appeared to have stepped from a novel by Arnold Bennett, quick to declare his lack of specialist knowledge, yet eager to give his modest opinions at length about contemporary art, before swelling with pleasure to introduce the poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy, whom he chose to regard as a local lass – the pride of Stafford – in spite of her origins in Glasgow. By now the gallery was full with an enthusiastic crowd and once Carol Ann declared the show open, Rob found himself inundated with a long line of fans eager to make his acquaintance. And as my pictures testify, dressed for the occasion in a bright pink gingham shirt, and with a playful nature and a mantle of unkempt curls comparable to the lion in the Wizard of Oz, he is the consummate showman.

Meanwhile, the rest of the citizens of Stafford spread out to scrutinise the immense detail of the works on display and I slipped among them, taking a closer look for myself. The bright energy of these intricate pieces draws your attention and then the subtle melancholy touches your heart. As I noted all the delighted faces, I realised it was an immense body of achievement and a phenomenal finale to a year of hard graft by Rob Ryan.

Then suddenly it was time to hurry back through the maze of streets to the railway station, riffle the vending machine for snacks and hop onto the last train back to London. Rob brought out his game of Boggle and the happy atmosphere in the darkened carriage rattling through the night was more like that of the returning leg of a school trip than you might expect after a major exhibition by a rising star – yet it was the ideal way to wrap up our adventure on the papercut express.

The paparazzi move in on Rob Ryan and Carol Ann Duffy, the poet laureate.

These two ladies wore dresses to camouflage themselves amongst Rob’s papercuts.

Rob enjoys a game of Boggle on the night train home from Stafford to Euston.

Your job is to take this world apart and put it back together again … but even better runs at the Shire Hall Gallery, Market Square, Stafford until Sunday January 9th and The stars shine all day too runs at the Air Gallery, Dover St, London until Saturday November 20th.

The Milk Float that became a Carnival Float

There was an air of mystery when Henry Jones, the third generation dairyman of Jones Brothers in Middlesex St, summoned me over to see him in the Summer. Closing the office door discreetly and looking me in the eye with a good-natured intensity, he revealed he had a story to tell me – but first I had to agree not to disclose it before the Lord Mayor’s Show. Once I had pledged my word, he proudly unrolled the blueprints upon his desk, confiding that Jones Brothers had accepted the honour of entering the Lord Mayor’s parade and had been placed at an impressive ninth position in the hierarchy of the running order, out of nearly one hundred and fifty entrants. The elaborate designs, which Henry showed me with such conspiratorial delight, were to transform a milk float into a model of one of the medieval gates of the City of London, complete with crenellated turrets.

In 1877, the first Henry Jones drove his herd from Abergavenny in Wales to Middlesex St and founded the dairy in Stoney Lane. Today his grandson Henry Jones presides over the longest established family business in Petticoat Lane, where his young son, the fourth Henry Jones, also works. This is a family with a long relationship with this particular web of streets at the boundary of the City of London. “I was born here,” Henry will tell you proudly, referring to the former dairy, which has since disappeared beneath the modernist concrete development where he now has his office.

So it was in the light of this family history that I came to appreciate Henry’s passionate enthusiasm for the parade, demonstrating that the language of pageantry is as vibrant as it ever was. The design of the gatehouse refers to the gate (or ‘Aldgate’) to the City of London that once stood here, where Geoffrey Chaucer once lived up above the gatehouse. Henry Jones – who is an independent councillor in this ward known as Portsoken – told me the name Portsoken is Norman French and refers to the ‘soke‘ (or district) outside the ‘port’ (or gate), once used by the knights of old for jousting. Consequently, he was employing a knight in armour to ride with a lance in front of his milk float, representing the ‘knightengild’ who were given land here for service to King Edgar. And the Portsoken Militia, the eighteenth century police force, reformed recently for ceremonial occasions would be marching alongside the milk float in their scarlet uniforms as guard of honour. Once Henry had conjured the beguiling image of how the float and entourage incarnated the history of Portsoken, he pointed out the Teddy Bears adorning the gatehouse, which were puzzling me. These were Henry’s whimsical gesture to his friend Mike Bear, the Alderman of Portsoken, who was due to become next Lord Mayor of London.

Henry’s conception was exactly in line with the original function of the parade when the burghers of the city used their floats to declare their status and demonstrate allegiance to the new Mayor. Eager to share his big secret, Henry was excited to inform me that he had already submitted his design to the Pageantmaster and won approval for its suitability. I promised to keep my lips sealed and he agreed to invite me over on the day before the Lord Mayor’s Show for a privileged glimpse of the grand design.

And so last week, I was ushered into the garage in Middlesex St where the float was being assembled behind closed doors. Men on ladders were attaching painted panels to the modest milk float and staging a metamorphosis worthy of the ugly duckling that became a swan. I shook hands with Stuart Stanley, veteran West End theatrical designer, who had been hired to fulfil Henry’s vision. As the gatehouse came swiftly together, Henry proudly explained that he and the other members of the Portsoken Ward Club, who were co-presenting the float, had been staging raffles and fundraising for four years to raise the money to realise this dream.

On the day of the parade, I greeted Henry outside the Guildhall. He was resplendent in his robes as a deputy Alderman and radiant with joy as he prepared to climb into the open coach to ride behind the Lord Mayor, while the rest of his family including his son, the fourth Henry Jones, drove the float. I never learnt what Mike Bear said when he first saw the bears upon the milk float transmogrified into a medieval gatehouse – on the glorious morning of his inauguration as the six hundred and eighty third Lord Mayor of London – but I am sure he cannot have been disappointed by this magnificent gesture which comprised a heartfelt tribute from Henry Jones, the third generation dairyman of Middlesex St.

Henry Jones on the day before the parade.

The milk float gets a makeover.

The team that transformed the milk float, Stuart Stanley the designer is on the far left.

A moment of hilarity for the Jones family prior to setting off.

In the centre is the fourth Henry Jones with his sister Lucy, and flanking them Trevor Jones and his wife Hazel.

Photographs copyright © Ashley Jordan Gordon

At the Lord Mayor’s Show

One of the highlights of November is the Lord Mayor’s Show, and each year I walk over to London Wall early in the morning where this extraordinarily multifarious parade gathers, to observe the elaborate preparations at close quarters, before it all moves off at eleven with the new Lord Mayor in his gleaming fairytale coach at its head. I cannot think of a more vibrant image of the diversity of human social endeavour – in all its paradoxes and contradictions – than this three mile long parade which takes over an hour to pass by. The City is closed off to traffic on the day and you walk through streets where a dreamlike hush presides to reach the assembly point where glorious chaos reigns as six thousand overexcited participants, both military and civilian, all take the opportunity to mingle and show off their gorgeous outfits.

Ever since I saw her remarkable photograph Girl on the Kingsland Road, which was shown as part of Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize at the National Portrait Gallery, I have admired the work of Ashley Jordan Gordon and so it was my pleasure to invite her to join me at the parade on Saturday as Spitalfields Life’s newest contributing photographer. In the time before the parade moves off, a curious photo party takes place when everyone wants their photograph taken and Ashley did her best oblige as many as she could. There was a pervasive surrealism to this situation where all were in costume and it engendered a joyful camaraderie of equals in which the boundaries of normal life dissolved. I saw a platoon of soldiers dancing with a rock band, children climbing on a tank and, among so many braided uniforms, it was only upon second glance that I realised two were toy soldiers from Hamleys.

Meanwhile down at the Guildhall, in an atmosphere of high seriousness, the berobed dignitaries of the City of London were gathering, the Aldermen, the Sheriffs and the former Mayors. For these people the parade is one event in an entire weekend of formal dinners and arcane rituals that attend the inauguration of the next Lord Mayor of the City of London. And in the surrounding streets, their transport awaited as it has done each year since the event was transferred from the river after a drunken flower girl unseated the Lord Mayor in his barge in 1710. An array of immaculately preserved historic carriages were poised with magnificent horses and freshly shaved coachmen in uniforms to match – perfect in every detail as if they had just travelled through time to be here that morning.

I stood at the junction of Lothbury and Moorgate, at the rear of the Bank of England, to see the parade pass by. Even here the parade outnumbered those in the crowd, enforcing the sense that this was an event for the participants, not a performance for an audience but a moment of glory for those involved, in which our role was simply to be their witnesses. A costume implies an assumed identity, yet for many in the parade their clothes exemplified their roles, carrying a reality established over centuries. It took me a while to accommodate to this notion that I was not witnessing a reenactment of an historical event but the event itself. The outfits were not fancy dress they were real.

When a marching band in ceremonial uniform comes marching straight towards you, with a hundred musicians with playing simultaneously, looking sharp and displaying perfect focus, and the loud music echoes through the narrow streets, then the vivid intricacy of the spectacle is overwhelming. Here we were in the heart of the ancient City of London. Soldiers who returned from recent conflict were met with cheers, and respectful applause was forthcoming for the nurses and firemen too, public services that we all value, now facing cuts. Among all the carnival animals, the puppies on leads, the seven man bicycle and the veteran trucks, it was sobering to see a bomb disposal robot in the parade, rolling along with the innocence of a remote controlled toy.

From the playful to the grim, from the charitable to the corporate, from the raucous to the majestic, all the pageantry on display fused with an inescapable emotionalism into a wondrous vision of humanity. From the dignified seniors to the young crazy ones dancing on floats, and from those who take themselves alarmingly seriously to dumb clowns with painted faces, there were so many different proposals of what it means to be human.

Photographs copyright © Ashley Jordan Gordon

Columbia Road Market 59

It was damp and misty and mild when I left Spitalfields early this morning to pay a call upon Stuart Crump, his daughter Alice, and Curly who works with them on their stall. A man of substance yet a relative newcomer to the market, Stuart has been in Columbia Rd for ten years and worked this pitch for the past two or three years. “My mum was a lecturer in floristry at the college in Southwark,” he explained proudly, “so when I left school in 1994, I opened a flower shop in Tottenham and then I had a place in the Edgware Rd, before I came here.” Stuart flies to Holland every Tuesday where he spends two days of each week buying plants for the coming Sunday at the huge auctions in the West Land. This week, Stuart has a fine selection of Orchids at competitive prices, and Chilli plants and Cyclamen are popular too.

At this point, Stuart’s enthusiastic daughter Alice bounced into the conversation to explain that she takes responsibility for rousing her father from his bed each Sunday at three-thirty in the morning, which caused Stuart to place his arm round her protectively as he rolled his eyes at the very thought of these reluctant awakenings. Alice takes great delight in the market, working here alongside her brother Charlie most weeks, and she is eager to follow her father into the family business, even though Stuart is dubious of the imminent changes coming to Columbia Rd. Stuart told me the stalls will be widened to twice the breadth and separated. “It won’t be good for the market, people like the hustle and bustle, and we haven’t got the stock to fill the width.” he confided with a shrug.

At the other end of the stall I had a chat with Curly. A celebrated character in the market, he has been employed on this pitch for the past twenty-five years – working for the previous owner Colin Roberts for twenty-three years. From Mondays to Fridays, Curly has a job at a tyre and bodyshop in Tottenham but, after a quarter of a century, his regular Sunday foray into market life has become the highlight of his week. “It’s something different, very sociable, you meet great characters and the stallholders are quite friendly,” he said, taking a bite from a hasty beigel, “It’s been like this as long as I’ve known it.”

Photograph copyright © Jeremy Freedman

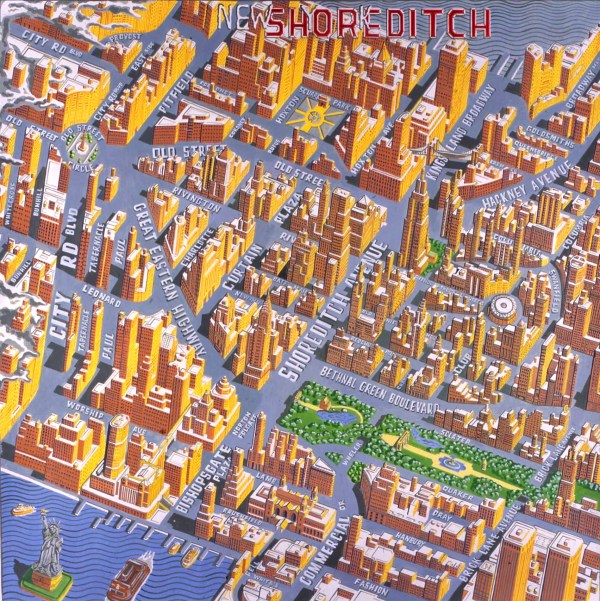

Adam Dant’s Map of Shoreditch as New York

“People do say they like the New Yorky feel, here in Shoreditch,” admitted Adam Dant with a wily smile and a discernible twinkle in his eye, when I asked him how he came to draw this map of Shoreditch as New York. In this arresting vision, (A double click will enlarge the map to fill your screen) Old St roundabout is transformed into Old St Circle, Arnold Circus Park becomes Madison Square Gardens and Liverpool St Station becomes Grand Central Station. In this metamorphosis, the buildings and terminology are Americanised too, Brick Lane becomes Brick Lane Avenue, Bethnal Green Rd becomes Bethnal Green Boulevard and Quaker St becomes simply Quaker. Commissioned in 2003 by the Shoreditch Map Company, the original painting now hangs above the table football machine in Bar Kick in Shoreditch High St, where Adam and I went to have a look at it yesterday. Unsurprisingly, we were told it is the subject of a great deal of discussion in the bar.

When you come to think about it, the comparison becomes less far fetched than you might assume, because Broadway in New York is along the line of an ancient pathway followed by the Algonquin tribe, whereas in Shoreditch, Old St follows the route of a primeval trackway of the ancient Britons, and Canal St in New York follows the route of the former canal whereas Shoreditch takes its name from the “Suer” that was once ditched and is now piped off. Both places are renowned for their mix of artists and immigrant culture, and down in Brushfield St, on the site of the Spitalfields Market, Adam has drawn New York’s Ellis Island building in acknowledgement of the immigrants who have come to New York and Spitalfields, defining the nature of these locations today.

Looking around the neighbourhood, you quickly come upon further clues. We have Rivington St here just as they do, and Broadway Market and Columbia Rd too, chiming with New York. And the extension of the Great Eastern Railway up to Old St created a narrow triangular plot, occupied by a tall tapered building at the bottom of Great Eastern St which is reminiscent of the Flat Iron Building. Many people live in lofts in this vicinity today just as you might find in Soho or Tribeca and, of course, we have Shoreditch House whereas in New York they have Soho House, though I am reliably informed our rooftop pool deck is bigger than theirs.

In Adam’s vision, the Bishopsgate Goods Yard is transformed into a park, something many residents would like to see. Wheler St crosses the yard beneath a bridge just as 79th St crosses Central Park, while the elevated garden upon the former railway arches that Adam has drawn resembles the Highline Park in Chelsea – and a similar proposal has been made here, to transform the continuation of the Bishopsgate Arches over in Pedley St into a raised park. On Sundays, you will find the Chelsea fleamarket in the West Village, and here in Sclater St and Bethnal Green Rd. In Summer months, young people fill Hoxton Square, just as their transatlantic counterparts fill Washington Square.

The impetus behind Adam’s map was the Situationists, who would take a map of Paris to the Sahara Desert, exploring the strange poetry of transferring a map from one area and applying it to another. Inspired by the Situationist movement, Adam had previously done a project of Reading as Rome, in which he staged a casting call in Reading for “Reading Holiday,” a remake of the classic Audrey Hepburn, Gregory Peck movie, relocated to Reading – using a Lambretta and back projection of the streets of Reading. “I tried to take photos of Reading where it could pass for Rome,” Adam explained to me with a smirk, as we walked back from Bar Kick to his studio in Club Row, “It was bloody difficult.”

Then we were both stopped in our tracks by an image on a passing courier truck in Redchurch St, showing New York viewed through Tower Bridge grafted onto the Brooklyn Bridge. But was it Tower Bridge joining the Brooklyn Bridge across the East River with Manhattan in the background? Or was it London with the New York Financial District transferred to Shad Thames? Was it London as New York or New York as London? We stood and looked at each other in amazement…

The courier truck in Redchurch St, is this London or New York?

You may like to take a look at Adam Dant’s Map of the History of Shoreditch and his Map of Shoreditch as the Globe. Next time, Shoreditch in the Year 3000. Adam Dant’s current exhibition Bibliotheques & Brothels runs at the Adam Baumgold Gallery, East 66th St, New York City until November 27th.

In & Out the Eagle Tavern

I wish you would take me out to the theatre. On these dark nights when the rain beats at my window and the wind moans down my chimney, I dream of leaving the gloomy old house one evening and joining the excited crowds, out in their best clothes to witness the spectacular entertainments that London has to offer. The particular theatre I have in mind is The Grecian Theatre attached to the Eagle Tavern in Shepherdess Walk, City Road between Angel and Old St.

The place seems to have developed quite a reputation, as I read yesterday, “The Grecian Saloon is really a hot house or a black hole, for the number of human beings packed in there every night would induce a supposition there was no other place of entertainment in London. At least two thousand persons were left unable to procure admission.” This was written in 1839, demonstrating that the popular art of having a good time – still pursued vigorously in the many pubs and clubs here today – is a noble tradition which has always thrived in the East End, outside the walls of the City of London.

“Up and down the City Road, in and out the Eagle, that’s the way the money goes…” The Eagle public house in the rhyme still exists to this day, though barely anything remains of the elaborate entertainment complex which developed there during the nineteenth century – apart from a single scrapbook that I found in the archive of the Bishopsgate Institute. All the balloon ascents, the stick fights, the operas, the wrestling and the wild parties may be over, and the thrill rides closed long ago, but there is enough in this album to evoke the extravagant drama of it all and fire my imagination with thoughts of glamorous nights out on the town.

You only have to walk through Brick Lane and up to Shoreditch on a Saturday night, through the hen parties and gangs of suburban boys out on a bevy, jostling among the crowds of the intoxicated, the drugged and the merely overexcited, to get a glimpse of what it might have been like two hundred years ago. With as many as six thousand attending events at the Eagle Tavern, we can assume that lines must have formed just as we see today outside nightclubs.

On the site of the eighteenth century Shepherd & Shepherdess Pleasure Garden, the Grecian Saloon developed at the Eagle Tavern to provide all kinds of entertainments, from religious events to conjuring and equestrian performances. There is a tantalising poetry to the hints that survive of these bygone entertainments, because sentences like “We are glad to find that little Smith has recovered her hoarseness.” and “We have little to find fault with save that the maniac was allowed to perambulate the gardens without his keeper.” do set the imagination racing. There are many fine coloured playbills in the cherished album that I hope to show you in coming weeks, crammed with enigmatic promises of exotic thrills. Take a look at the plates below and wonder who exactly was the beautiful Giraffe Girl, or General Campbell, the smallest man in the world. Amongst so much hyperbole there is a disappointing modesty to learn that the central attractions are merely supported by the “artistes of acknowledged talent.”

Elaborate pavilions with all manner of special effects were constructed at the Grecian Saloon, which in turn became the Grecian Theatre in 1858 where Marie Lloyd made her stage debut, aged fifteen. Eventually the building was acquired in 1882 by General William Booth of the Salvation Army and the parties came to an end. Yet this site saw the transition from eighteenth century pleasure garden to nineteenth century music hall. And when you come to think of the many thousands of souls who experienced so much joy there over all those years, it does impart a certain sacred quality to this location, even if it is now mostly occupied by the Shoreditch Police Station.

Watercolours of the New Grecian Theatre in 1899, built during the management of George Augustus Oliver Conquest in 1858 and later purchased by General William Booth of the Salvation Army.

All images copyright © Bishopsgate Institute