Spitalfields Antiques Market 22

This is Nancy Lee Child, a weaver who came from New York in 1969 and ran a weaving shop in Walthamstow for thirty-six years until she sold it in 2009. “When I retired at sixty-eight, they said, ‘What are you going to do? You’re an a empress and your empire is your life,'” Nancy confided to me, her sharp blue eyes sparkling with intensity. “But I’d had enough. This is my empire now, it’s six feet long and two feet wide.” she said, gesturing proudly to her stall and crossing her arms in contentment, “I’m in charge, I employ me and I answer to me.” As well as being a virtuoso at the loom, Nancy collected wooden boxes for forty years until she had so many she could not get into her living room. “Now the word is sell ’em and you ain’t buyin’ any more,” she informed me with gruff enthusiasm, “Every one I have, I like and now I’m trying to persuade the public to like ’em too.”

This is Jo & Kelvin Page who deal in drinking and smoking collectibles. “It’s my wife’s baby,” said Kelvin, passing me over to Jo. “We’ve been collecting for a long time,” responded Jo with a diplomatic smile, casting her eyes fondly over all their fancy ashtrays and kitschy cocktail paraphernalia,“I admit I am compulsive, if I see it I have to have it.” “We like to own it for a little while and then we sell it,” continued Kelvin, in tactfully qualification. “We like the nineteen fifties,” declared Jo helpfully. “Neither of us smokes, but we do like a drink,” announced Kelvin, catching Jo’s eye as they exchanged a private smile.“But we don’t overdo it,” added Jo prudently, just in case I imagined they enjoyed a decadent lifestyle, and revealing she is a Paediatric Audiologist for the rest of the week.

This is Tim Mason who has been trading in “quirks of art” for the past twenty-five years. “I used to have a flat full of weird and interesting things, but I am selling it all now I’ve become a dad because I need to keep the wolf from the door,” he confessed to me proudly with a grin untinged by regret, adding, “I’ve still got quite a nice art collection.” Tim’s stock ranges from taxidermy through vintage copies of Playboy to anatomical charts. “It serves me well coming to Spitalfields” he explained, setting his jaw purposefully,“because even if I have a slow day selling, all the other dealers are here so I can do a lot of buying.” If you look closely you can see Kermit the Frog to the left of Tim. “I’ve always had him, he’s been hanging around for years and no-one ever buys him. He’s my mascot,” confided Tim shyly, raising one eyebrow and revealing an unexpected whimsical side.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

You also like to look at

Spitalfields Antiques Market 1

Spitalfields Antiques Market 2

Spitalfields Antiques Market 3

etc

Rupert Blanchard, Salvager & Maker

If you go North from Shoreditch High St, up the Kingsland Rd, under the railway bridge, and turn immediately left down a tiny nondescript alley, you come to a metal door without any sign, that is the entrance to the secret world of Rupert Blanchard. Here you will find many wonders. You ring the bell and wait patiently for a while, and then you hear footsteps inside before the door opens and a skinny young man with a long nose and lanky hair leans out, clutching his black cat, and smiles amiably. This is Rupert.

Step inside and find yourself in what was formerly part of the Shoreditch Police Station and latterly a furniture factory, and currently the workshop, store and dwelling of Rupert Blanchard. Up on the wall are prized specimens of Rupert’s tubular chair collection, displayed in the way that others show hunting trophies. Turn and observe Rupert’s collection of errant drawers that have lost their siblings, all stacked up neatly. Step into the next room and admire Rupert’s collection of screen-printed milk bottles artfully arranged upon a roof beam. Beyond you will find a smaller room, with further collections stacked upon shelves. It goes on and on, like the opening shot of Citizen Kane.

“My obsession with drawers and collecting began at an early age,” Rupert admitted to me, “As a child, I would enjoy riffling through a large bank of watchmaker’s drawers that lined the corridor to my grandmother’s kitchen. Each tiny drawer was full of every useful object that you could ever need, an odd screw, a piece of string, folded plastic bags, buttons, paper and pens. Everyone should have a useful drawer.”

Rupert has developed a trained eye for the beauty of the disregarded and, as a consequence, lives at the mercy of his compulsion to hoard it, taking him to at least three car boot sales a week and connecting him to an elaborate network of scavengers, junk dealers, house clearance people, skip raiders and demolition workers. “Time will run out before the rubbish does,” he pronounced, pulling a long quizzical face, shaking his head and crossing his arms in bewilderment at his crazy hoarding instinct. Yet everything here is wonderful in its way, and Rupert has found means to give new life these artifacts once their original incarnation is defunct.

Taking lone drawers that survive from broken chests of drawers, damaged doors and fragments of enamel signs, Rupert contrives elegant pieces of furniture which allow the beauty of their constituent parts to be appreciated anew. It is a question not just of the aesthetic quality of the elements but also of their history – a personal matter for Rupert, witnessing the endless destruction that goes on in house clearance as the furniture of a dying generation is trashed. “You can see when people have saved money to buy a quality piece of furniture,” he informed me in melancholic contemplation of a sole wardrobe door, placing his hand upon it tenderly, “These are people’s lives.”

There is both poetry and humour in Rupert’s work, which plays upon the tension between an appreciation of the soulful nature of the material and the contemporary sensibility of his conception. And, there is an elegant conceit to his whole endeavour. Based here in this old furniture factory, and working with metalworkers and woodworkers based in the East End, using salvaged timber – much of which is from the East End – he has created a new industry producing appealingly idiosyncratic furniture, shop fittings and interiors to fulfil an ever-growing demand.

The inspired anarchy of Rupert’s sensibility is irresistible to me, and I especially like the cabinets laminated with fragments of old enamel advertising signs. Some were found patching up holes in leaky barns, others had been cut in pieces and were discovered in scrap yards and markets, none were in a condition to be of interest to collectors. Rupert built these cabinets from the recycled plywood that is the basis of most of his furniture, which comes from hoardings around building sites, providing a plentiful supply in the East End. The tops of the cabinets are teak reclaimed from a school science lab, still with its graffiti and marks that evidence its use – and even the hinges and screws are recycled from other furniture.

Everything that Rupert collects becomes a potential piece of a puzzle, just waiting to be reassembled in an unexpected new way to create unique furniture which declares the eclecticism of its origins. He has just completed a refit of Ally Capellino’s shop in Calvert Avenue and his work is more in demand than he can supply, yet in spite of Rupert Blanchard’s success, I do get the feeling that it is all an elaborate excuse for him to pursue his first love – trawling Outer London car boot sales for the lonely drawers and broken doors that are his unlikely passion.

Cabinet made from scraps of aluminium sections of a decommissioned London bus.

Designs copyright © Rupert Blanchard

You might also like to take a look at

The Handbells of Spitalfields

The joyous art of handbell ringing has survived because it was kept alive by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. “For many years we were the only company in the world making handbells,” revealed Kathryn Hughes – joint-Master Bellfounder with Alan Hughes – as we sat together in the peaceful office of the ancient foundry while outside the traffic roared down the Whitechapel Rd . “Handbell ringing survived because of one person, Anne Hughes, my husband’s grandmother.” Kathryn continued, “She was a solo handbell ringer, and that’s how Alan’s grandfather Albert met her, he heard the sound of her playing handbells at a concert. And for a wedding present, he gave her a thirty-chime set of handbells.”

As a lover of bells and bellringing, I am always pleased to visit the famous Whitechapel Bell Foundry, the centre of the world of tintinnabulation, responsible not just for casting big bells like the Liberty Bell and Big Ben, but also fine handbells. And, continuing the work of Anne Hughes, Kathryn herself is also a handbell ringer. “I do ring, yes,” she admitted with professional reserve – being an authority on handbells and presiding with formidable expertise over the handbells side of the business. “In the nineteenth century, traditional handbell ringing was very popular in the North of England,” she informed me, adopting an elegiac tone, “most villages had teams of handbell ringers just as they had brass bands, but the First World War decimated the teams and the whole thing died the death after World War II.”

“Albert Hughes wanted to stop making them,” confided Kathryn, almost embarrassed to admit it now and raising her eyebrows in barely concealed disapproval, “but his wife said, ‘Over my dead body.'” Anne’s stubborn refusal to let the art die was vindicated by the revival in handbell ringing which occurred in the latter half of the twentieth century, and today the art is thriving again. Now, in an exciting development, to complement the wide range of traditional compositions that exist, the bell foundry is supporting three commissions of experimental pieces for handbells by young composers to be performed as part of the Spitalfields Festival in the charismatic surroundings of Dennis Severs’ House next week.

I stepped by to join a rehearsal in one of the modest panelled rooms upstairs at the foundry, where a handsome array of gleaming brass bells lay upon the table, arranged in order of size. Taking it in turns to work with the two handbell players, the three composers drifted in and out from the next room, so I took the opportunity to have chat with them there, while the chimes continued on the other side of the door. In recent months, all three visited the time capsule house in Folgate St and have created pieces inspired by its mysterious interior, and conceived to be performed in its distinctive sound spaces.

“I’ve never worked with handbells before,” Shiva Feshareki declared, her dark pupils shining with excitement, “it’s been an opportunity to think in a different way.” The composer known only as Gameshow Outpatient agreed, “We’ve all gone in completely separate ways, which I think is good.” he said. Yet, seduced by the beauty of the sound of the bells, these two have both created semi-improvised compositions that allow the bells to speak for themselves. “I am using just four handbells, and I want to draw people to become aware of the quality of silence that exists in the house.” explained Shiva, “There are some church bells in the distance that I hope they will hear during my performance.”

Gameshow Outpatient has written a piece to be played in the withdrawing room on the first floor entitled “Dead Reckoning,” referring to the early eighteenth century when sea captains were expected to retain Greenwich Mean Time internally through physical memory during their voyages. “I’ve got a headache from listening to the opening of it over and over,” he said, rolling his eyes in playfully self-deprecation,”but the next section sounds really beautiful by comparison – thank goodness for that!”

“It’s nice to have the opportunity to be more intimate, you can encourage detailed listening when people are up close.” Edmund Finnis told me. “A lot of my music is quite fast paced and energetic but this is more meditative,” he confessed. He has sampled handbells and manipulated their sound, to accompany the live performance and provide an additional dimension of resonance.“I’m using a lot of handbells and I like the idea that people don’t know what they’re going to get,” he announced with a wicked smile, adding, “I haven’t cluttered it with too many notes, it’s about the joy of sound.”

These three premieres are part of a jubilant evening’s event celebrating bells that also includes performances in the Charnel House, and in the Masonic Temple beneath the former Great Eastern Hotel, entitled “Song of the Bell” and curated by Spitalfields Music Associate Artist Mica Levi – destined to bring Spitalfields alive to the echoing tintinnabulation of bells next week.

The composer known as Gameshow Outpatient.

You can book tickets for “Song of the Bell,” the bell-themed event curated by Mica Levi in Spitalfields on Tuesday 14th June at Spitalfields Music.

You may also like to read about

Beating the Bounds at the Tower of London

The Liberty of the Tower of London was once defined by the distance of an arrow’s flight from the outer walls of the Tower – an area independent of the City of London, and free of buildings so that those inside the Tower might see approaching forces. Yet although the modern city has crept up around the ancient Tower, the markers that define this territory still exist and every three years upon Ascension Day, the Yeoman Warders emerge from the Tower in procession to beat the bounds, reminding the neighbours of their former jurisdiction.

This year, John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder led the procession, for the fourth and final time in his tenure, with majestic aplomb. Behind him came the Chaplain of the Tower, followed by a bold troupe of boy scouts brandishing willow wands, followed by the choir and master of the music, followed by the Governor of the Tower, followed by the Officers of the Tower and all the families, including the children and even grandchildren of the Yeoman Warders, also waving their willow wands. And this year, I was invited to join as the penultimate member of the procession, before Alan Kingshott, the Yeoman Gaoler who followed up behind me with a great big axe. Meanwhile Spitalfields Life contributing photographer Sarah Ainslie ran ahead to capture the event with her lens.

When I arrived on Tower Green, I was delighted to be welcomed by the residents assembling and for the first time I encountered the entire community of people for whom the Tower is their home. All the tourists had gone and the informal atmosphere was that of a village square where the all inhabitants were gathering in the golden rays of the setting sun for a shindig, and we set off in high spirits as if it was the town carnival or we were off to the choir picnic.

It was a startling moment of worlds meeting when we emerged from the West Gate of the Tower where crowds of tourists lingering by the gift shop, who could hardly believe their eyes at this sudden eruption of the medieval world into the modern city. Cameras popped right, left and centre, and we acquired an accumulating entourage of excited photographers that grew and grew, in spite of our police escort, as we traced our route around the boundary.

At each marker, John Keohane raised his silver mace with the finial in the shape of the Tower and called his instruction to “Mark Well!” in his gruff voice, and the boy scouts and children of the Tower and some members of the choir and even a few adults, including the chaplain, took it as their cue to give it a great enthusiastic thwacking with their sticks – an inexplicable source of great hilarity and satisfaction to those involved. No doubt the atmosphere would have been different if the children had been beaten upon each of the boundary stones, as was the original practice to instill the boundaries forcefully into their minds.

Yet it was not long before a reminder of the once aggressive nature of the endeavour appeared, when we confronted the party from the parish of All Hallows by the Tower who were also beating their bounds, recalling “the riotous assembly” of 1698 who “protested in most vile manners at the disputed boundary betwixt the Tower and All Hallows Parish Church.” It was a face-off – like gangs of rival football fans – with our opponents consisting of City of London worthies, a gang of schoolchildren with sticks and the Vicar of All Hallows by the Tower. It might have turned ugly and required the police escort to keep the opposing parties apart, if the conflict had not been limited to huffing and puffing. It might have ASBOs all round, because the Tower kids and the boy scouts were up for a fight, and the Yeoman Warders were brandishing some serious weaponry, but fortunately the encounter was quelled by the exchange of civilized words.

The Governor of the Tower said, “We greet our neighbours of All Hallows and assure them that, unlike our predecessors of three hundred years ago, we come in peace.” And then a relieved Vicar replied, “We greet you in peace.” But then, just to make it clear who was the boss, the Governor of the Tower instructed them to take off their hats – oh so politely. “Before we part, may I ask the gentleman of both parties to doff their hats?” he said. There was a momentary hiatus before the party from All Hallows assented, and it made not a sliver of difference to the politics of the exchange that not even one of them wore a hat.

Then, in the manner of the fabled waters of the Red Sea, the crowd from All Hallows parted and we walked across the road to Trinity Square where one of the markers was inside the entrance of the magnificent Trinity House, indicated by brass strips set into the floor. Now we were in the City proper and commuters stopped in their tracks to wonder at our unlikely pageant that had materialized in the midst of the rush hour. “They must think that we’re mad!” whispered one of the Officers of the Tower – a distinguished gentleman in a dark suit who walked alongside me – when he saw the astonished faces of his counterparts from the City, as they hurried off towards Tower Hill tube.

If we were mad, our madness was sanctioned by the police who turned all the lights to red for our unlikely crew – of Beefeaters in red Tudor uniforms with gold braid, overexcited youths and choir singers with sticks, Officers of the Tower in suits and various family groups straggling along – permitting us all to weave our way through each of the pedestrian crossings that span the major roads converging at Tower Hill. The sun was declining in the West and the Thames was sparkling gold, as we returned to the waterfront and made a sharp right, crossing the middle drawbridge and re-entering the Tower a half hour after we left.

After one verse of the national anthem and photographs upon Tower Green, the Chaplain collected the willow wands off everyone just to make sure there was no funny business later. Then the assembly dispersed and we joined John Keohane and the boys of the Royal Eltham Scout Group for a refreshing glass of orange juice in the crypt beneath the chapel, where they store the bones of those unfortunates who were executed at Tower Hill. There, John introduced me to his wife, his daughter and his grandson, all of whom had participated in beating the bounds. It was a real family occasion.

Colonel Dick Harrald, Governor the Tower of London

Alan Kingshott, Yeoman Gaoler and John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

The Ceremony of the Lilies & Roses at the Tower of London

The Bloody Romance of the Tower

John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

Petticoat Lane Market 2

Benny Banks is a redoubtable operator who has worked in Petticoat Lane for over sixty years, putting out the stalls for the traders. “I’ve lived my life in this market,” he declared to me, leaning upon the bonnet of his red Jaguar in the midst of the lane and displaying his perfect gleaming teeth in a magnificent smile of satisfaction at the narrow territory around Middlesex St that is his beloved manor.

“When I was a kid in Wentworth St, we were always out in the streets. Except we had to stay in the yard on Sundays because we couldn’t afford posh clothes and everyone else was in their Sunday best. My mother used to pawn my dad’s suit and get it back by Sunday. Yet we never went hungry, even though there were four of us boys in one room and six girls in the boxroom. The house was spotless, everything stank of carbolic and bleach. We were proud people and I learnt to keep my bits of sticks clean, it’s rubbed off on me. It’s been a hard life but I am a proud man.

My mother was a flowerseller and wreathmaker with a licence to sell on Petticoat Lane and on the Cut outside the Old Vic – that’s where I started at threepence a bunch when I was seven or eight. My father was a fruitseller who bought his goods from Covent Garden, Spitalfields and Borough Market. He was a pikey and she was a gipsy. There was ten of us in the family and we all worked for our parents each day from four in the morning until ten o’clock at night.

Before they licenced Petticoat Lane, the only way you could get a stall was to get on a pitch and stay there all night. We used to light a fire and sit on the pitch, even in Winter. If anyone tried to push us off, there was a street fight. My father was a streetfighter and he fought Queensberry rules. They fought in Spitalfields. He would set about them and they would leave us alone, so we always had our pitch The lane finished at six and anything we had left we sold door to door, all night, me and my brothers and sisters. People always bought from us because we were so poor and our clothes were in rags. They bought out of pity and they would give us a cup of tea and a piece of cake.

I didn’t go to school, and I had to get along as best I could because I had no education and no-one would employ me except as a labourer. I was offered a job in the docks, checking goods off a list, but I can’t read or write. I did odd jobs for the Asians. I built the first restaurant for the Asian community and I started the first minicab company for them – doing airport runs in a van and they put their suitcases in at one pound a head. They still know me as ‘Mr Benny’ among the Asians.

My goal was to buy all the barrows in Petticoat Lane. It was like a village, everybody in Petticoat Lane was Jewish and they had them for generations and there’s no way they would sell them. But I got a lucky break when I bought ten barrows in Bakers Yard. All of a sudden, the people in the market, one after another, came to me wanting to sell their barrows but I had nowhere to keep them at first – it was a nightmare. There were only two left I didn’t buy, one was Dave King and the other was Joe Feinstein.

I was always told that one man could not own Petticoat Lane’s nine hundred barrows. It was something that could not be done and they said the logistics were impossible because you have to push them all around and set them out. But I owned the whole of Petticoat Lane by 1979 – my goal was fulfilled.

The secret of it was I used to get the down and outs from the hostels to help me set up the stalls at night. As long as the vagrants could lift the stalls, they were employed – because I couldn’t get any straight person to work in the market . They were social misfits. I gave them fifty pence and a bottle of methylated spirits each. They’d go to Spitalfields Market afterwards and sleep among the boxes, and sometimes trucks ran over them or they fell in the fire. And that’s how I used to run the market.

I still come to the market seven days a week. I can’t keep out of Petticoat Lane. I always have to be doing something. I’ve never stopped. All my ex-wives are good friends, they never really divorced, only in name. They worry about me. If I was ill they’ll be there, or sending food. I lost them over work. My children never had birthdays, just as I was brought up. I bought secondhand for my children and if they wanted anything, I said, “You earn half, I’ll give you half.” I didn’t have the time for them unless they were interested in work. I don’t know anything else. I’m awake at six and I work until six.”

Today there are only sixty stalls left out of the nine hundred that once comprised the glorious realm Benny presided over. In his own estimation the lane is “completely gone,” yet it remains endlessly fascinating to him as the arena of conflict and intrigue where he forged his identity through guts and graft. He won his single-minded quest to acquire ownership of his personal universe, Benny Banks will always be the man who bought Petticoat Lane Market.

Benny Banks among the stalls in 1983

Portraits copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Click here to watch a film of Petticoat Lane Market in 1926

You may also like to read

James Boswell’s East End

Yesterday afternoon, I went up to a leafy North London suburb to meet Ruth Boswell – an elegant woman with an appealing sense of levity – and we sat in her beautiful garden surrounded by raspberries and lilies, while she told me about her visits to the East End with her late husband James Boswell who died in 1971. She pulled pictures off the wall and books off the shelf to show me his drawings, and then we went round to visit his daughter Sal who lives in the next street and she pulled more works out of her wardrobe for me to see. And when I left with two books of drawings by James Boswell under my arm as a gift, I realised it had been an unforgettable introduction to an artist who deserves to be better remembered.

From the vast range of work that James Boswell undertook, I have selected these lively drawings of the East End done over a thirty year period between the nineteen thirties and the fifties.There is a relaxed intimate quality to these – delighting in the human detail – which invites your empathy with the inhabitants of the street, who seem so completely at home it is as if the people and cityscape are merged into one. Yet, “He didn’t draw them on the spot,” Ruth revealed, as I pored over the line drawings trying to identify the locations, “he worked on them when he got back to his studio. He had a photographic memory, although he always carried a little black notebook and he’d just make few scribbles in there for reference.”

“He was in the Communist Party, that’s what took him to the East End originally,” she continued, “And he liked the liveliness, the life and the look of the streets, and and it inspired him.” In fact, James Boswell joined the Communist Party in 1932 after graduating from the Royal College of Art and his lifelong involvement with socialism informed his art, from drawing anti-German cartoons in style of George Grosz during the nineteen thirties to designing the posters for the successful Labour Party campaign of 1964.

During World War II, James Boswell served as a radiographer yet he continued to make innumerable humane and compassionate drawings throughout postings to Scotland and Iraq – and his work was acquired by the War Artists’ Committee even though his Communism prevented him from becoming an official war artist. After the war, as an ex-Communist, Boswell became art editor of Lilliput influencing younger artists such as Ronald Searle and Paul Hogarth – and he was described by critic William Feaver in 1978 as “one of the finest English graphic artists of this century.”

Ruth met James in the nineteen sixties and he introduced her to the East End. “We spent quite a bit of time going to Blooms in Whitechapel in the sixties. We went regularly to visit the Whitechapel when Robert Rauschenberg and the new Americans were being shown, and then we went for a walk afterwards.” she recalled fondly, “James had been going for years, and I was trying to make my way as a journalist and was looking at the housing, so we just wandered around together. It was a treat to go the East End for a day.”

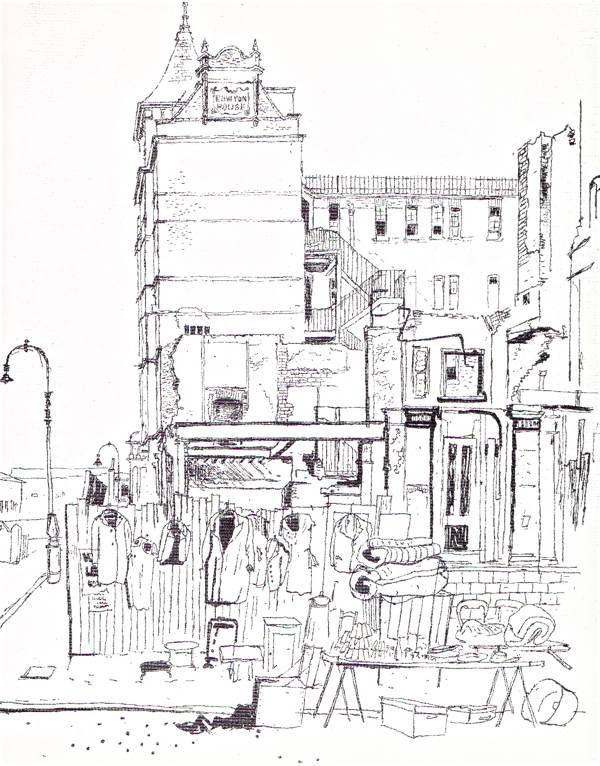

Rowton House

Old Montague St, Whitechapel

Gravel Lane, Wapping

Brushfield St, Spitalfields

Wentworth St, Spitalfields

Brick Lane

Fashion St, illustration by James Boswell from “A Kid for Two Farthings” by Wolf Mankowitz, 1953.

Russian Vapour Baths in Brick Lane from “A Kid for Two Farthings.”

James Boswell (1905-1971)

Leather Lane Market, 1937

Images copyright © Ruth Boswell

You can see more work by James Boswell at www.jboswell.info and copies of “James Boswell Unofficial War Artist” are available from Muswell Press.

You might also like to take a look at

In the footsteps of Geoffrey Fletcher

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Living in Spitalfields, an area of London defined by its markets, I am constantly aware of the traders and the ever-changing drama of street life in which they are the star performers that draw the crowds. Interviewing the market traders in Spitalfields has taught me that although they are here to make a living, it is an endeavour which may be described as culture as much as it is commerce. In fact, the markets prove so engaging to some as a location of social exchange that they carry on coming for the sake of it, even if they are not making any money.

This fascination of mine with the culture and performance of market places has led me to delight in the diverse sets of the Cries Of London for the pictures they give of street traders in the capital down through the ages. Even though they were frequently sentimentalised, these portraits also reveal the affection with which Londoners held the traders, celebrating the ingenuity of the identities created by vendors and casting them as the celebrities of the thoroughfare – collectively expressive of the very personality of the city itself, when the streets were full of people with wares of every description to sell.

With the Cries of London, there is always a story behind each of the portraits and Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries from the nineteenth century, hand-tinted and produced in a pamphlet with a blue paper wrapper for sixpence, engages the readers with rhymes that complement the pictures and invite respect for the hawkers. The middle class woman in the frontispiece leading her daughter down the street shows deference to a Lavender Girl in a dress stained with mud around the hem, and this pamphlet can be read an interpretation of the lives of the traders for the mother to read to her child.

The Band Box Man is selling the hat boxes that are product of his cottage industry, manufactured at home and sold on the streets, while the Lavender Girl walked into London carrying the lavender she picked that morning in the fields. The Vegetable Seller is pursuing a trade as a Costermonger, buying his fruit at the wholesale market and hawking it around the street, as many once did at Covent Garden and Spitalfields Markets. And we are reminded that the Knife Grinder provides a public service in the home and workplace, while the Mackerel Girl has no choice but to carry her basket of fish around the city from Billingsgate, which she herself may not get to eat. The mishap of the Image Seller, in comic form, even illustrates the vulnerability of the street seller who relies upon trading to earn a crust and the responsibility of the customer to permit them a living.

For hundreds of years, popular prints and pamphlets of the Cries of London presented images of the outcast and the poor, yet permitted them dignity in performing their existence as traders. The Cries of London celebrate how thousands sought a living through street-selling and, by turning it into performance, gained esteem and moral ownership of the territory – both transcending their economic status and creating the vigorous culture of street markets that persists to this day.

Images copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to take a look at

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders