John Claridge’s Spent Moments

Self-Portrait with Keith (standing behind with cigarette), E7 (1961).

“We still meet up for a drink and put the world to rights.”

Here is the young photographer John Claridge at seventeen years of age in 1961, resplendent in a blue suede jacket from Carnaby St worn with a polo neck sweater and pair of Levis, and bearing more than a passing resemblance to the character played by David Hemmings in ‘Blow-Up’ five years later.

On the evidence of this set of photographs alone – published here for the first time – it is apparent that John loves people, because each picture is the outcome of spending time with someone and records the tender moment of connection that resulted. Every portrait repays attention, since on closer examination each one deepens into a complex range of emotions. In particularly intimate examples – such as Mr Scanlan 1966 and the cheeky lady of 1982 – the human soul before John’s lens appears to shimmer like a candle flame in a haze of emotionalism. The affection that he shows for these people, as one who grew up among them in the East End, colours John’s pictures with genuine sentiment.

Even in those instances – such as the knife grinder in 1963 and the lady on the box in Spitalfields 1966 – in which the picture records a momentary encounter and the subjects retain a distance from the lens, presenting themselves with a self-effacing dignity, there is an additional tinge of emotionalism. In other pictures – such as the dance poster of 1964 and the windows in E1 of 1966 – John set out to focus on the urban landscape and the human subjects created the photographic moment that he cherished by walking into the frame unexpectedly. From another perspective, seeing the picture of the mannequin in the window, we share John’s emotional double-take on discovering that the female nude which drew his eager gaze is, in fact, a shop dummy.

For John, these photographs are not images of loss but moments of delight, savouring times well spent. If it were not for photography, John might only have flickering memories of the East End in his youth, yet these pictures capture the people that drew his eye and those that he loved half a century ago, fixing their images eternally.

Across the Street, E1 (1982) – “I did a double-take when I first saw this. In fact, it was a mannequin in the window. Still looked good.”

School Cap, Spitalfields (1963) – “I just found this surreal. It was as if the man behind was berating a nine-year-old who couldn’t care less.”

Two Friends, Spitalfields (1968) – “They were walking along sharing one piece of bread.”

The Box, Spitalfields(1960) – “I came across this lady sitting on an orange box, there was nothing else around. Then she got up and walked off with her box.”

Labour Exchange, E13 (1963) – “Never an uncommon sight.”

Ex-Middleweight Boxer, Cable St (1960) – “We were talking about boxing when he just gave me the thumps-up.”

Knife Grinder, E13 (1966) – “Every few weeks he would appear at the end of the street. Quite a cross-section of people had their knives sharpened!”

Mr Scanlon, E13 (1966) – “My next door neighbour. Always with a wicked sense of humour and an equally wicked smile.”

The Doorway, E2 (1962) – “To this day I would still like to know where her thoughts were.”

Crane Driver, E16 (1975) – “He could balance a crushed car on half a crown and still give you change.”

59 Club, E9 (1973) – “The noise of the pinball machines with the sound of the jukebox playing Jerry Lee.”

A 7/6 Jacket, E13 (1969) – “He had a small shed where he sold anything he could find, which he collected in a small handcart.”

A Portrait, E1 (1982) – “This special lady asked me ‘Why do you want to photo me?’ I replied ‘Because you look cheeky.’ This is the picture.”

Scrap Dealer, E16 (1975) – “This was shot in Canning Town, near the Terry Lawless boxing gym.”

The Step, Spitalfields (1963) – “A kid at play.”

Dance Poster, E2 (1964) – “I was taking a picture of the distressed posters when he glided past.”

The Windows, Spitalfields (1960) – “Behind every window.”

My Mum & Dad, Plaistow (1964) – “Taken in the backyard.”

Fallen Angel, E7 (1960) – “There were a lot of fallen angels in the East End.”

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

You may also like to take a look at

Along the Thames with John Claridge

At the Salvation Army with John Claridge

(Click to enlarge and explore this drawing)

In recent years, Redchurch St has become the conduit through which the culture of the New East End has been channelled into the Old East End, as the street that was once part of the infamous Old Nicol slum has been transformed into London’s most fashionable destination. At one end is Shoreditch, lined with new media enterprises and expensive bars, while at the other end is Brick Lane, with its street markets, leather shops and beigel bakeries. And in the middle is Adam Dant, the last artist left on Redchurch St, living and working in the midst of the hullabaloo.

Celebrated as a cartographer extraordinaire, Adam took his satirical pen in hand to create this epic social panorama of The Meeting of the Old & the New East End in Redchurch St populated with hundreds of characters, both real and mythological, that compose the identity of this notorious thoroughfare. At the far end, drunken Foxtons estate agents characterised by their pointy shoes and spiky haircuts collapse in a drunken heap while leaving The White Horse strip pub. Ken Livingston is about the run them over by driving a bendy bus round the corner as Boris Johnston falls off the open platform of a passing Routemaster. All this drama, yet you are merely on the threshold of Redchurch St.

Meanwhile, amongst those representing the Old East End, you may recognise Richard Lee, the bicycle parts seller whose family have been trading on Sclater St since 1880, and the young Charlie Burns, the legendary waste paper merchant who died recently at ninety-six, portrayed here at seven-years-old, put in a halter by his father to pull the waste paper cart round the City. Elsewhere in this extravagant fantasy (eerily not too far from the reality) the iconography of Old and the New East End appear to have become mixed up as members of Shoreditch House have relocated from their rooftop swimming pool to a flooded hole in the road and a pop-up brothel opens for business nearby. Amongst the mayhem unleashed in this tiny street by the surreal culture clash between flashy new money and long-term poverty, spot Terence Conran, Keira Knightley, Bud Flanagan, Pearlies behaving badly, a pack of dogs from Hoxton and urban foxes on the prowl.

“We are presented with a plastic version of the authentic, here at the City fringe,” Adam confided to me in a discreet whisper as we walked together down the street in question, “In Redchurch St, behind this scruffy fascia of poverty, people on laptops are designing apps.”

For local cognoscenti, Adam’s drawing is a chance to test your people-spotting skills while, for the rest of us, it is a welcome opportunity to chuckle at human folly.

Drawing copyright © Adam Dant

You may like to take a look at some of Adam Dant’s other work

The Redchurch St Rake’s Progress

Map of the History of Shoreditch

Map of Shoreditch in the Year 3000

Map of Shoreditch as the Globe

Map of the History of Clerkenwell

Map of the Journey to the Heart of the East End

Click here to buy a copy of The Map of Spitalfields Life drawn by Adam Dant with descriptions by The Gentle Author

Phil Maxwell’s Old Ladies

Photographing daily on the streets of Spitalfields and Whitechapel for the last thirty years, Phil Maxwell has taken hundreds of pictures of old ladies – of which I publish a small selection of favourites here today. Some of these photos of old ladies were taken over twenty years ago and a couple were taken this spring, revealing both the continuity of their presence and the extraordinary tenacity for life demonstrated by these proud specimens of the female sex in the East End. Endlessly these old ladies trudge the streets with trolleys and bags, going about their business in all weathers, demonstrating an indomitable spirit as the world changes around them, and becoming beloved sentinels of the territory.

“As a street photographer, you cannot help but take photos of these ladies.” Phil admitted, speaking with heartfelt tenderness for his subjects, “In a strange kind of way, they embody the spirit of the street because they’ve been treading the same paths for decades and seen all the changes. They have an integrity that a youth or a skateboarder can’t have, which comes from their wealth of experience and, living longer than men, they become the guardians of the life of the street.”

“Some are so old that you have an immediate respect for them. These are women who have worked very hard all their lives and you can see it etched on their faces, but what some would dismiss as the marks of old age I would describe as the beauty of old age. The more lines they have, the more beautiful they are to me. You can just see that so many stories and secrets are contained by those well-worn features.”

“I remember my darkroom days with great affection, because there was nothing like the face of an old lady emerging from the negative in the darkroom developer – it was as if they were talking to me as their faces began to appear. There is a magnificence to them.”

Photographs copyright © Phil Maxwell

See more of Phil Maxwell’s work here

Celebrating Joseph Grimaldi

Zaz the clown spins a disc for Joseph Grimaldi

Last week saw the one hundred and seventy-fifth anniversary of the death of the world’s most famous clown, Joseph Grimaldi, and a small group of devotees with painted faces gathered – as they do each year on the anniversary – at the former graveyard of St James’ Pentonville Rd to celebrate his memory, in the place where the bones of the great man lie interred.

The church was deconsecrated long ago and the churchyard cleared, reconstituted now as Joseph Grimaldi Park with his tombstone given pride of place in a location twenty feet from where he is actually buried. Nearby, the traffic roars up and down the Pentonville Rd with a ferocity unknown in Grimaldi’s day, yet the remains of thirteen hundred souls still lie here peacefully and, even though Grimaldi was decapitated before burial at his own request out of a morbid fear of being buried alive, his spirit becomes manifest each year when the clowns arrive to pay tribute.

On an occluded summer’s day, the sun broke through as the ‘Joeys’ came stumbling in one by one, wearing their big boots, enacting their crazy poetry of gurning, and bringing delight with old gags and dumb tricks. Resplendent in a garish suit of Buchanan tartan, Mattie, the curator of the clown museum and local resident who has lived thirty-five years years in Clerkenwell, gave a plain speech of remembrance before laying flowers for Grimaldi. At a distance, Puzzle the silent clown, wiped tears from his eyes as he stood under an umbrella in the sunlight while water pumped up through the handle cascaded down over the shade, making a suitable gesture to honour the man who developed the notion of the modern clown that is universally recognised today.

“It’s been low-key for donkeys’ years and we thought it would be nice to pay a bit more attention to it,” explained Bluebottle, rubbing his hands in delighted satisfaction at the turnout. A clown of twenty years experience, he was speaking to me as official secretary of Clowns International, the world’s largest clown organisation. By contrast, Fiasco the clown has only been doing it for six months, eagerly confiding that her sole ambition is “to bring people happiness and to entertain handicapped children.” Meanwhile, Zaz the clown who has been clowning since he was eleven and is now thirty-three, revealed that he had performed for Madonna’s children and been flown to India just to entertain at a party. And Jolly Jack confessed that he began clowning at the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977 and never looked back. They were a quorum of fools, and we delighted at their high jinks and idiocy.

At the entrance to Joseph Grimaldi Park, two metal coffin lids set into the ground invite you to dance upon them, triggering the sound of bells. They propose the triumph of clowning over death and offer a metaphor for the human condition – that we are all but dancing upon our graves. Clowning and mortality are inextricable in this way. We need clowns to humble us by reminding us of our essential foolishness, to encourage us to seek joy where it flies, and to confront us with our flawed humanity, lest we should make the mistake of taking ourselves too seriously.

Fans young and old gather to celebrate Joey the clown.

Mattie the clown.

Fiasco the clown with ‘Daddy.’

Bluebottle the clown.

Jolly Jack the clown.

Puzzle the clown.

Professor Geoffrey Felix’s Punch & Judy Show – Mr Punch is 350 years old this year.

Musical coffins commemorating Joseph Grimaldi and Charles Dibdin invite you to dance upon them.

[youtube uP-gMPl0XG0 nolink]

A sombre moment of remembrance at Grimaldi’s grave.

Joseph Grimaldi (18th December 1778 – 31st May 1837)

You may also like to read about

Yet More Trade Cards of Old London

After publishing selections of trade cards that might have been found in the eighteenth century by rummaging in a hypothetical drawer, searching down the back of a hypothetical sofa or under a hypothetical bed, it is my pleasure to show this further selection discovered beneath the hypothetical floorboards.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to see my earlier selections

At the Fruit & Wool Exchange, 1937

After granting a temporary reprieve in March, Tower Hamlets Council meets today to decide whether to grant permission to demolish the historic Fruit & Wool Exchange in Spitalfields, and I am publishing these excerpts from a brochure to promote the Exchange produced in 1937.

You, as a fruit grower, are interested in three things. Growing your fruit. Shipping your fruit. And marketing your fruit. Of these three essentials, the first is entirely your own responsibility, the second is partially under your guidance, and the third?

You may ask “Why is the London Fruit Exchange the best place to auction your fruit?” We answer the question in two ways. Firstly, we say, “Because the Exchange is the finest example in the world of a specialised fruit distribution centre.” Secondly, we point to the high reputation of the six Brokers who constitute the Exchange – John & James Adam & Co Ltd, Connolly Shaw Ltd, Goodwin Simons (London) Ltd, J.C. Houghton & Co (London) Ltd, Keeling & White Ltd, and Knill & Grant Ltd. One was flourishing back in 1740 and all have unblemished histories of financial soundness and high integrity. And these qualities, being so old are all the more jealously guarded.

Here you may be sure of a price that is as high as the market will stand. You may be sure that your fruit will be sold quickly while it is worth the most money. So sure may you be of these things, that, though many thousands of miles may separate you from your ships in the London Docks, you can always be certain that not a penny of your money is being thrown away by carelessness or delay.

It is often easier to understand the workings of a business if one knows how and why it was started – and so we will begin our story of the present Fruit Exchange by telling briefly where its roots lie, and how it grew to its present importance.

A century ago, there flourished in London four well-known Auction Fruit Brokers. To the fruit trade they were known as “The City Brokers.” With their headquarters at the City Sale Room, they handled a large proportion of London’s fruit business throughout the great industrial expansion of nineteenth century England. But with the twentieth century came greater and greater consumption of fruit, and in addition, London became a centre of fruit distribution for the Continent as well as the United Kingdom.

By 1929, the four Brokers of the City Sale Rooms made a great decision. They decided that by intelligent co-operation, it was in their power, and in the interests of the fruit trade, to form a central exchange for buyers and sellers. And so, in conjunction with the Central Markets Committee of the Corporation of London, these six firms organised and caused to be built the London Fruit Exchange. The first auction took place here in September 1929.

As an example of a specialised fruit distribution centre, the London Fruit Exchange is the finest in the world – in its one building are complete services for warehousing, sampling, buying and distribution, besides social amenities for the buyers who congregate there. Sales by auction are held here on every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Every sale day of the week, an average of 40,000 and 50,000 packages are offered for sale. On some occasions as many as 100,000 have been catalogued for sale on one day.

On the ground floor of the Exchange are spacious showrooms, in which can be exhibited 2,500 sample packages at one time. Here from 8am onwards, the buyers and the auctioneers examine and value the goods before the sales start. The Showrooms are connected with the Sales Rooms by electric indicators, which show at a glance which broker is selling at the moment and in which Sales Room. Immediately adjacent to the Sales Rooms are numerous telephone cabinets connected to a telephone operator. From these, buyers may swiftly communicate with their principals in Great Britain and the Continent to discuss the state of the market.

The sales take place from 10:30am in two inter-communicating auction rooms, providing seating for 1,000 buyers. These are fitted with every modern device for making business quick and easy. In each room, the Auctioneers speak into microphones connected to loudspeakers, which bring them into instant touch with every part of the room in which they are selling.

The important railways of Great Britain have offices within the Exchange itself, conveniently situated for the immediate use of buyers, and telewriters are installed in the Brokers’ offices which instantly link up with the principal ports of the United Kingdom, giving the latest market information up to the last second before the fruit is sold.

By these facilities, and by comfortable seating and central heating, the work of selling goes on smoothly and quickly. The seller has displayed his goods to his best advantage. The buyer is at his ease, and knows that he is dealing with honest men. Is it any wonder that prices at the London Fruit Exchange are uniformly good?

On the ground floor and basement of the Exchange, is warehouse accommodation capable of holding 200,000 packages. The basement is fed by electrical conveyors, gravity rollers and chutes, from the loading bays at ground floor level. There are fourteen loading bays, each wide enough to take two vehicles per bay. Twenty-eight vehicles can thus be loaded or unloaded simultaneously. Special traffic men are employed to regulate the vehicles, so that immediately a vehicle is loaded or unloaded, it is called out and another takes its place.

To do this work, a permanent warehouse staff is employed. During the busy season, it is necessary to employ additional labour, ranging from thirty to a hundred porters daily. At such times, the warehouse opens at 6am, and the business of loading and unloading, piling and sorting, continues smoothly and quickly until 10pm. At times, over 25,000 packages have been received and 25,000 packages despatched in one day. Taking the average weight of a package at 84lbs, this gives a total tonnage handled, piled and sorted in one day of 2,000 tons. All this work is done in a cool, even temperature, maintained on even the hottest days of summer by batteries of electric fans.

We say to you, the grower, and therefore the prime mover in this great industry, “We believe that you could choose no better way to consistently high prices and fair, reputable dealing, than of consigning more and more of your fruit to the handling of the London Fruit Exchange – the finest fruit auction centre in the world.”

Examine the Planning Application with English Heritage’s objections on pages 27 & 28 here

Read about the campaign to save the Fruit & Wool Exchange here

Visit the developer’s website here

Take a look at Paul Johnston and Dan Cruickshank’s alternative proposal here

Sign the petition to save the Fruit & Wool Exchange here

You may also like to read about

Return of the Hamburgs & the Mekelburgs

Solomon & Joseph Mekelburg at Solomon’s stall in Goulston St, around 1940.

For centuries the histories of the Hamburg and Mekelburg families were intertwined, living in parallel streets in the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam – even before coming as economic migrants to Spitalfields in the second half of the nineteenth century, where they intermarried, lived, and worked for three generations.

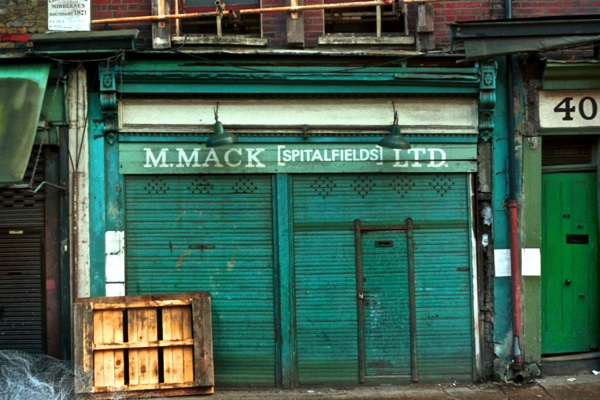

While the story of these two families and their complex interrelationships is without limit, the Spitalfields chapter begins with the arrival of Benjamin Hamburg in the nineteenth century and ends with the closure of M.Mack over a hundred years later. But it is a tale that would not be told at all, if it were not for John Marx, the grandson of Philip Mekelburg and Sarah Hamburg who were married at Sandys Row Synagogue in 1914. Five years ago, upon his retirement, John set out to trace descendants of all nineteen children of the first generation Mekelburg and Hamburg families in this country, and – astonishingly – he brought more than fifty of them together for a family reunion at Sandys Row earlier this month.

Cigarmakers Benjamin Hamburg and Isaac Mekelburg first came to London in the eighteen sixties and eighteen seventies respectively, and both married women who had come been born in Amsterdam. Benjamin and his wife Flora had ten children that survived, while Isaac and his wife Mary had nine. The Hamburgs lived at 24 Shepherd St (now Toynbee St) and the Mekelburg family lived round the corner at 2 Butler St (now Brune St), dwelling in close proximity just as they had done in Amsterdam. Twenty-three people lived in just five rooms and nine of the siblings were married nearby at Sandys Row Synagogue, including two marriages between the families.

All of the Mekelburg brothers worked in the fruit and vegetable trade. Solomon and Joseph Mekelburg had barrows in Petticoat Lane, and their endeavours evolved by 1922 into a wholesale business in the Spitalfields Market known as M. Mack, managed by Morris and Philip Mekelburg, that ran until the eighties when it closed prior to the move of the market to Leyton. The Hamburgs were known to have worked as upholsterers, shoe clippers, costermongers or tailors and, as the children of both families married, many moved from Spitalfields up to the newly built Boundary Estate occupying up to a dozen flats there, enacting the same culture of families living close-by that they had brought from Amsterdam.

John Marx’s research would barely have been possible without the internet. “It would have taken me a lifetime!” he acknowledged, “My son was looking on the web and discovered things about my mother’s family I didn’t know. I realised there was more to it than I ever imagined and curiousity drove me forward” As John discovered his living relatives that were previously unknown to him, he wrote to them all and then set out around the country to meet them face to face, pursuing a quest that culminated in the gathering in Spitalfields.

Anyone that walks through Spitalfields – more than anywhere else in London – cannot fail to wonder what became of all the people who have passed through these streets over the centuries, and the fascination of the Mekelburg/Hamburg reunion was that it provided a tangible answer to this intriguing question.

Most of those who came along did not know each other previously and many had not even been to Spitalfields before. People who had formerly been strangers discovered they were relatives as they visited the locations familiar to their forbears – which imbued the day with a certain sombre reverence as they recognised the poverty and deprivation of these recent ancestors. Yet it was John Marx who found the words which best expressed the emotional meaning of the occasion.“We remember the hardship they endured so that their children and their children’s children would benefit, and we have benefitted – which means they were successful.” he concluded, casting his eyes around the throng in the atmospheric old synagogue at Sandys Row where nine of the family had once married, in an earlier chapter of the same story which had brought everyone there that day.

Amelia & Isaiah Hamburg with their baby Mary, born in 1901.

First cousins Mary Mekelburg and Mary Hamburg

Amelia & Bella Mekelburg

Aaron Hamburg, c.1920.

Solomon Mekelburg and his stall in Goulston St in the twenties.

Joseph Mekelburg (right) and his son Teddy (left) behind their stall in the thirties.

Solomon and his daughter Mary in the forties.

Solomon Mekelburg in the fifties.

Premises of M.Mack (trading name of Mekelburg family wholesale business) in the eighties.

The reunion of the descendants of the Hamburgs and the Mekelburgs at Sandys Row Synagogue.

The bimah cover at Sandys Row Synagogue created for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 has been brought out for the current jubilee.

M.Mack photograph copyright © Philip Marriage

Reunion photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Find out more at www.sandysrow.org.uk

You may also like to read about