At Tom’s Flat

Tom in his living room

And so it turns out that Tom the Sailor, who was living in a van near Brick Lane, has had a flat all along but the conditions were such he would rather not stay there even in the severest winter weather. “If you saw it, you wouldn’t believe it!” he declared, conjuring both the enigma and wonder of it – and by way of issuing an invitation to me to visit. A gentleman of soulful character, Tom is to be seen almost every day on Brick Lane with his dog Matty, and is blessed with a gift for rhetoric and storytelling that I find irresistible – which explains how I came to find myself sitting at the front of the top deck on a bus with him going through Bethnal Green yesterday on the way to his flat.

“Do you know why I sit on the front of the bus? Because I can see what’s being thrown out, that’s the big advantage of a bus. You’re high up and you can see everything, if you’ve got a trained eye like mine. It’s better than a lorry, or a car, or a bike. Look there’s a bed there being thrown out! And when you do see something, you get off. I can’t believe the gear I find. I can tell by the way it’s piled up whether it’s on the way in or on the way out. These are the things you look for, you train yourself. Last week, I saw this gear, coming out of one of the wheelie bins. I got off and went through the lot, there was cine-cameras and cameras, handbags and lipstick of all sorts, all brand new. It had to be the Poles, they always throw everything out when they move. My Christ! I had it all in big black bag and I got back on the bus, and I struggled.”

During this speech, Tom was scanning the kerb on either side, as eagle-eyed and alert as a hunter, focusing on the familiar bins, the dumpsters and places where people abandon things which comprise the landmarks along his route and that have provided the source of his trading income on Brick Lane for decades. “There’s so much to tell, but the story you would learn it’s unbelievable,” he assured me as we reached the stop where we had to get off, “Just remember, I used to have a beautiful home.”

As we navigated the narrow lanes to reach Tom’s flat, he made a few detours to examine some piles of debris and peek inside a few bins. “See I can’t help it!” he informed me with a helpless grin, spreading his hands demonstratively, as if to renounce responsibility for these habitual actions.

When we reached the entrance to the block, Tom showed me a new sign warning tenants not to put anything in corridors – raising his eyebrows in disdain – and then as we approached his flat – with a defiant gesture – he indicated a dressing table next to the front door. Then, “Man, I’ve got to get a torch,” he announced theatrically, to himself, before turning to me and emphasising, “Remember, there’s a reason for everything.”

He opened the red door and went inside, and I followed in anticipation. The smell was ripe, and the air was heavy and humid. Two rooms were crowded with junk leaving narrow passages littered with old newspapers and waste paper, just wide enough to walk through. Following Tom’s flickering torch, I entered the living room where the contents were stacked almost to the ceiling. I concentrated upon Tom’s speech to avert my attention from retching in the foul atmosphere. He showed me the power meter that had been cut off but still clocked up a tariff. He explained the newspapers were because of a flood and pointed out the holes in the ceiling where the water came through. He told me that the possessions of his wife who died of cancer were under the pile. And he told me that he was the last resident remaining from when he moved in thirteen years ago, now that the building has been sold off to a management company.

In the next room, Matty was sleeping upon a mattress which, on further examination, belonged to a bed submerged under the clutter. Beside it were Matty’s water dish and food bowl, and a portable stove where Tom cooked for himself without leaving the bed. Tom told me he lived here happily until three years ago when he let his son have it for a year. Since then, his son moved on and Tom became so alienated by the interventions of the new management company that he preferred to sleep in his van. Yet now the van is sold, he is back in the flat and resolute that nothing will remove him.

I found the grief of the place unbearable, as if someone had died there long ago and Tom was the ghost of that person lingering among the debris of a life. “Why don’t you get rid of all this stuff?” I asked, impatient to dispel the torpid mood of stagnation,”Why don’t you sell it?” Tom looked at me critically and shook his head in disappointment. “You don’t understand, do you?” he said.

“You don’t understand an orphan. My wife didn’t understand an orphan. My kids didn’t understand an orphan. Only I understand an orphan, because I was born an orphan. You might say ‘You’ve got kids, so you’re not an orphan anymore,’ but you’re wrong. An orphan is one who never had a mother and father. If you’ve never seen or known them, you are an orphan. You think as an orphan.

If you knew what I have gone through you wouldn’t believe it. In an orphanage, you go from a cot to a bed in a dormitory and you don’t know what they’re going to do to you in there. One boy says, ‘Do you want a pillow fight with me?’ and you say ‘Yes’ and grab your pillow, and he hits you on the head with a pillow case that has got something metal in it. You put your hand up and it cuts your fingers open – Look! I still have the scar – but you don’t tell anyone, you cover your hands, and next day they find you in the bed unconscious and blood everywhere. They never dare do it again. Do you know why? When I came back, I stabbed the geezer. They got the message – Stay away from me! And this was how I was brought up.”

We were walking back through the streets and Tom spoke his thoughts out loud to counteract my silence. “I haven’t told you the stories, I’ve only made a start. If I told you all the stories you wouldn’t believe it.” he asserted again. “Are you with me?” he kept repeating after each statement, to disturb the mass of thoughts that were whirling in my head.

“Are you lonely?” I asked him when we were sat together on the top of the bus again.”I am not lonely, I’ve got my dog. He’s with me twenty-four hours a day. He sleeps in my bed because he likes the smell of me.” Tom barked in reply, his eyes glittering as he returned to his monologue about the perceived conspiracy to remove him from his flat, and asserting his passion to resist it with fighting talk. “If you’ve been sunk in a sailing ship in the Atlantic as a young man and survived that – I was only thirteen at the time – what harm can they do to me?” he insisted.

And then Tom brought out a spare travelcard with eight pounds on it and offered it to me, as a gift to console my unspoken distress at his flat. “What they’re doing to me is keeping me going – it’s the excitement. I don’t care, it just flows off of me. I can’t complain, I have had a good life. I’ve got three boys and a girl.” he admitted, apparently reconciled to his circumstance. I took the travelcard in my hand, touched by his generosity. I was overwhelmed by Tom’s flat. “Have you got a bit wiser now?” he asked.

“I can see what’s being thrown out, that’s the big advantage of a bus.”

“Man, I’ve got to get a torch.”

“Remember, there’s a reason for everything.”

“I am not lonely, I’ve got my dog.”

“If I told you all the stories you wouldn’t believe it.”

Tom the Sailor, more formally known as Thomas Frederick Hewson Finch.

Tom outside the eighteenth century Drapers’ Almshouses across the road from his flat.

You may also like to read about

Some East End Portraits by John Claridge

Boy, E7 1961 – “He was the son of a friend of my father’s – Peter, an electrician who worked down the docks. To find out if anything was live, he’d stick his finger in the socket!”

Eaten up by the consumption of chocolate, this lad is entirely unaware of the close proximity of photographer John Claridge‘s lens. And, judging from the enthusiasm with which he is sticking the chocolate in his mouth, it looks like he took after his father when it came to poking fingers into holes.

Published for the first time, these vibrant photographs reveal the range of John’s approaches to portraiture. “Most of the time I ask,” he admitted to me, “and sometimes people ask me to take their pictures, but at other times you just see something and grab it. I’ve no single way of doing it.”

“I talk to them and it is through talking that you can open a door,” he continued, ” if you’ve known someone for a while, it is very different from if they only have ten minutes to give me their soul. So I never set people up to look foolish, I treat them with dignity because I need to win their trust.”

Offering a variety of moods and contrasted energies, these portraits share a common humanity and tenderness for their subjects. In particular, John’s self-portrait fascinates me. He says he took it in a semi-derelict toilet “for the hell of it,” but, in retrospect, it is emblematic of his extraordinary project – he was a photographer in a world that was spiralling down.

The body of work from which these photos have been selected – of which I have published hundreds in weekly instalments over the last few months – is believed to be the largest collection of images by any single photographer covering this period in the East End. In their quality, their number, and their range, they will come to represent the eye of history – but it makes them especially interesting that they were taken by an insider. When he took these photographs, John Claridge was an Eastender looking at the East End. John was taking portraits of his own people.

Clocking Off, Wapping 1968 – “He was a neighbour and I arranged to meet him down at the warehouse after work.”

Boxer, E16 1969 – “A chap putting on his wraps at Terry Lawless’ gym in Canning Town. I walked in and I was talking to the guys – and I just took the picture.”

Man at Booth House Salvation Army, Whitechapel 1982 – “I printed this picture for the first time the other day. They guy is somewhere else, but I didn’t notice until this week the man with the camera taking the picture on the television.”

Children at the Salvation Army Care Centre, Whitechapel 1970s – “Some children were permanently in care and others were just there for the day. I can’t tell which these were. People only came in these places if there was a problem, if their dad was in the nick or their mum couldn’t take care of them.”

Worker at the Bell Foundry, Whitechapel 1982 – “You expect a man who works lugging bells around to be brawnier than this, but he’s got his cardigan on and he looks like a watchmaker.”

Antiques Dealer, E6 1962 – “He sold everything, penny farthings, paintings, cigarette cards … everything. I used to go down there and see him, and have cup of tea and poke around.”

My Dad in the Back Yard, E13 1961 – “He had a deck chair and he sat in the garden with a cup of tea. I said to him, ‘Just sit and don’t do anything,’ and he’d just laugh. Great times! There isn’t a day that goes by when I don’t think about him.”

Mates in Wapping, 1961 – “I think we were going down to the Prospect for a drink. I was seventeen years old, so everyone’s seventeen. It was Sunday and everyone’s got polished shoes. I haven’t been in touch, but they’re still around – I haven’t seen them for years.”

Man and Mannequin, Spitalfields 1965 – “This was just off the market. He’s listening to a portable radio on earphones. It looks like he has a mate with him and their bellies are almost touching.”

Edward and Mrs Simpson, Spitalfields 1967 – “Another kind of portrait. I love the military jackets for sale and Edward’s got one on, while Wallace is hiding and pointing him out.”

Caretaker at Wilton’s Music Hall, Wapping 1964 – “It said, ‘Please ring for caretaker.’ So I rang for the caretaker. I said, ‘Are you the caretaker?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ So I said, ‘May I take a photo of you?’ and he gave me this lovely smile.”

Self-Portrait, E14 1982 – “It was an old toilet in Poplar, in use but at the end of its day. The mirror was still there. People asked me if I ‘d done self-portraits, so I thought I’d do one down there for the hell of it.”

My Mates, 1961 – “We all went out from the East End for the day somewhere. It might have been Southend, Brighton or Clacton, but I remember it was freezing.”

Man in a Knitted Hat, E17 1964 – “This was at Walthamstow Town Hall. He’d finished his fight, had a shower, put his hat on to keep warm, and we were chatting over a cup of tea. He was a visiting fighter from the States and his shirt says, ‘The Big Apple.'”

Woman in Her Kitchen, E12 1969 – “She had no home and a young family, and was staying in a building that was derelict. The council didn’t want people to use it, so there was barbed wire outside. It was a shelter, and they asked me to go down and take pictures to show how people were living there.”

Tony Moore and Joe Gallagher, Wapping 1970 – “Tony was an ex-heavyweight boxer and Joe was my ex-father-in-law. They look like they’re about to sort somebody out.”

My Friend JB, E14 1972 – “We met when we were both fifteen years old and working at McCann Erickson. We were both Eastenders. He was an incredible designer. He had a wonderful sense of humour. He died of a heart attack. He looked like a villain, and one day we went to New York together, and were in Little Italy in a restaurant, and this guy came in and said, ‘I remember you!’ I said, ‘We’d better get out of this place.'”

My Son, Spitalfields, 1982 – “I went along on a home visit with the Salvation Army and I saw this picture on the sideboard. I said, ‘Is that your son?’ and she said, ‘Yes, he was killed in the war.'”

Headless Bear, E2 1964 – “I just came across it. He had his head burnt off. He was lying there at the edge of a bomb site.”

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

You may also like to take a look at

Along the Thames with John Claridge

At the Salvation Army with John Claridge

A Few Diversions by John Claridge

Signs, Posters, Typography & Graphics

Views from a Dinghy by John Claridge

In Another World with John Claridge

Joanna Moore at the Tower Of London

Yeoman warders’ cottages built into the wall of the Tower

Spitalfields Life Contributing Artist Joanna Moore spent a couple of days at the Tower of London this week and made these sketches published here today. Joanna lives nearby the Tower in Wapping and walks past it every day, yet when she got inside she found the sunshine and heat of recent days proved to be a challenge. “Everyone thinks it must be lovely drawing outside in the sunshine, but in fact the light bleaches all the colours and it’s better in the early morning, when there are more subtle tones,” Joanna confessed to me. So Joanna was given a dispensation to arrive before the Tower opened to the public, which is when most of these drawings were done. “It was a privilege to have the Tower to myself and I found more of the character of the place became apparent outside visiting hours,” Joanna confirmed in excitement, “so now I want to go back and do more drawings in the early mornings.”

The Byward Tower with the Bell Tower in the foreground.

Looking over Henry VIII’s Watergate and Baynard’s Tower to the Thames.

Looking through the arch of the Bloody Tower to the White Tower.

Looking from the roof of the White Tower to the Thames.

Entrance to the White Tower.

The eleventh century Chapel of St John in the White Tower is the oldest church in London.

Visitors sheltering from the rain beneath the arch of the Byward Tower.

Alan, Yeoman Warder.

“Merlin the Raven is the cleverest raven at the Tower, she buries half of her breakfast under a tree outside the Queen’s House and returns to eat it later.”

Traitors’ Gate where Anne Boleyn and Thomas More entered the Tower.

Looking towards Tower Green, where Catherine Howard and Anne Boleyn had their heads chopped off.

Looking across St Peter ad Vincula, the Chapel Royal constructed in 1512, towards the Gherkin.

In the gallery of St John’s Chapel in the White Tower.

The White Tower – construction began at the order of William the Conqueror in 1078.

Drawings copyright © Joanna Moore

Residents of Spitalfields and the Tower Hamlets gain entrance to the Tower for one pound on production of an Idea Store card.

You may like to read these other Joanna Moore stories

The Spitalfields Nobody Knows (Part One)

The Spitalfields Nobody Knows (Part Two)

The Whitechapel Nobody Knows (Part One)

You may like to read these other Tower of London stories

Alan Kingshott, Yeoman Gaoler at the Tower of London

Graffiti at the Tower of London

The Beating of the Bounds at the Tower of London

The Ceremony of the Lilies & Roses at the Tower of London

The Bloody Romance of the Tower with pictures by George Cruickshank

John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

Constables Dues at the Tower of London

Kallistratus Wraith, Pirate Goth Magician & Corsetier

“I love not being like everybody else.”

In spite of what you might assume, Kallistratus Wraith, Pirate Goth Magician & Corsetier, was given his name at birth. “My parents were quite eccentric, they christened my elder brother and sister Arachnid and Grendel, so as soon as they were old enough they went to a lawyer and changed their names to July and John – but I like my name, I think it suits me,” Kallistratus admitted. “It means dweller from the deep, that’s why I have this,” he added, pointing to the octopus tattooed on his brow by means of explanation.

You may have seen Kallistratus – widely known as Kato – and his wife Pip in the streets of Spitalfields over the past year, looking strangely at home in their fearsome goth outfits among the old buildings, as if the entire neighbour had been constructed as some extravagant steampunk fantasy and they were creatures that had emanated from its deepest recesses. “She’s a rockabilly goth whereas I am more a piratey goth,” Kato informed me helpfully, exercising his lilting Herefordshire accent, and opening my eyes to the precise distinctions of gothdom.

“Pip and I met at a goth club, filled with goths gathered together. We already had our goth styles and we were both types that we both liked. So that was part of the attraction and we were more or less married twenty minutes after we met. At the time, Pip was living in a shared house with friends that she didn’t like and I was living in a house on my own, so we went down to get her things that night and she moved in with me and that was eighteen years ago.

We came here when our friend opened her goth shop, we worked for her before when she had a shop in Camden. It was ten years ago we met Sam, Pip worked for her at first but then she had an accident and broke her leg so I went in to help her out in the shop and the customers seemed to like it. I am a magician, I do magic acts and stage shows but when I am not doing that I am the corsetier in the shop, I measure the ladies for their corsets and fit them for their corsets. I love to seeing women in corsets and I’ve always been interested in Victorian styles.

Even when I was a little kid, I used to have long black painted fingernails at school and long black dyed hair. My dad was a magician and he collected old props and we used to have a skeleton in the front room. This was in Herefordshire. He died when I was ten and after that I wanted to do magic for him, to carry it along. I went to stay with my step-father who was my father’s best friend who was also a magician and lived in the Hollywood Hills in Los Angeles for many years.

I love not being like everybody else. Most of our friends are “different” though we do have some friends who dress quite ordinary. I don’t dress to make a statement, I wear what I want to wear and I’m not interested in what people think. You do get people calling abuse at you from cars sometimes but it’s just part and parcel, I ignore it. Nobody ever says it to your face. They see people like me and they think we are devil-worshippers and baby murderers, but if anyone comes to speak to us we are always friendly.”

Kato invited me to visit his tiny purple flat in Whitechapel that he shares with Pip. Stepping into the half-light of the living room, where sunlight filtered through closed curtains I could distinguish three sinister figures lurking in the gloom, life-size animatronic figures of familiar villains from horror movies. Yet Kato stood between these hell-raisers and extended his arms affectionately to introduce them to me as his cherished companions. Elsewhere in the room, horror babies nestled upon a rocking chair, a disembodied head lay upon the table and a skeleton presided over all, just as it did in Kato’s childhood home.

Kato told me that he used to perform magic at London fetish clubs but they have tailed off with the recession and he is looking forward to returning to the Holllywood Hills where the culture of goth horror magic remains vibrant. Kato delights in these transgressive areas of culture where the collective unconscious becomes tangible and, for him, the past is not something over and done but a continuum in which we can participate through our daily actions.

Entirely comfortable with dark areas of human experience that fill many with dread, Kato retains an upbeat courteous manner and is an engaging advocate for the seductions of fantasy. The ideal corsetier.

Kallistratus at home in Whitechapel with his animatronic moving horror figures.

A cosy corner of the living room.

Kallistratus Wraith, Pirate Goth Magician & Corsetier.

You may also like to read about

East End Desire Paths

In Weavers’ Fields

Who can resist the appeal of the path worn solely by footsteps? I was never convinced by John Bunyan’s pilgrim who believed salvation lay in sticking exclusively to the straight path – detours and byways always held greater attraction for me. My experience of life has been that there is more to be discovered by stepping from the tarmac and meandering off down the dusty track, and so I delight in the possibility of liberation offered by these paths which appear year after year, in complete disregard to those official routes laid out by the parks department.

It is commonly believed that the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard invented the notion of “desire paths” (lignes de désir) to describe these pathways eroded by footfall in his book “The Poetics of Space,” in 1958, although, just like the mysterious provenance of these paths themselves, this origin is questioned by others. What is certain is that the green spaces of the East End are scored with them at this time of year. Sometimes, it is because people would rather cut a corner than walk around a right angle, at other times it is because walkers lack patience with elegantly contrived curved paths when they would prefer to walk in a straight line and occasionally it is because there is simply no other path leading where they want to go.

Resisting any suggestion that these paths are by their nature subversive to authority or indicative of moral decline, I prefer to appreciate them as evidence of human accommodation, coming into existence where the given paths fail and the multitude of walkers reveal the footpath which best takes them where they need to go. Yet landscape architects and the parks department refuse to be cowed by the collective authority of those who vote with their feet and, from time to time, little fences appear in a vain attempt to redirect pedestrians back on the straight and narrow.

I find a beauty in these desire paths which are expressions of collective will and serve as indicators of the memory of repeated human actions inscribed upon the landscape. They recur like an annual ritual, reiterated over and over like a popular rhyme, and asserting ownership of the space by those who walk across it every day. It would be an indication of the loss of independent thought if desire paths were no longer created and everyone chose to conform to the allotted pathways instead.

You only have to look at a map of the East End to see that former desire paths have been incorporated into the modern road network. The curved line of Broadway Market joins up with Columbia Rd cutting a swathe through the grid of streets, along an ancient drover’s track herding the cattle from London Fields down towards Smithfield Market, and the aptly named Fieldgate St indicates the beginning of what was once a footpath over the fields down to St Dunstan’s when it was the parish church for the whole of Tower Hamlets.

Each desire path tells a story, whether of those who cut a corner hurrying for the tube through Museum Gardens or of those who walk parallel to the tarmac for fear of being hit by cyclists in London Fields or of the strange compromise enacted in Whitechapel Waste where an attempt has been made to incorporate desire paths into the landscape design. I am told that in Denmark landscape architects and planners go out after newly-fallen snow to trace the routes of pedestrians as an indicator of where the paths should be. Yet I do not believe that desire paths are a problem which can be solved because desire paths are not a problem, they are a heartening reminder of the irreducible nature of the human spirit that can never be contained and will always be wandering.

The parting of the ways in Museum Gardens.

The allure of the path through the trees.

In Bethnal Green, hungry for literature, residents cut across the rose bed to get to the library.

A cheeky little short cut.

An inviting avenue of plane trees in Weavers’ Fields.

A detour in Florida St.

A byway in Bethnal Green.

Legitimised by mowing in Allen Gardens, Spitalfields.

A pointless intervention in Shadwell.

Which path would you choose?

Over the hills and faraway in Stepney.

The triumph of common sense in Stepney Green.

Half-hearted appropriation by landscape architects on Whitechapel Waste.

A mystery in London Fields.

A dog-eared corner in Stepney.

The beginning of something in Bethnal Green.

Daniele Lamarche’s East End

Cheshire St Doorway – “He once ran after me into the beigel shop and urged me to follow him. I had no idea what he wanted, but he led me back to my car on Bethnal Green Rd to show me that I’d left my keys in the door – he was desperately worried I would lose them. It made me chuckle after that when passers-by clutched their shoulder-bags firmly and crossed the street at the sight of him.”

Photographer Daniele Lamarche came to stay in a flat in Wentworth St for two weeks in 1981 and ended up staying on for years. Working as an international news scriptwriter for Independent Television News in Leadenhall St, Daniele first visited Brick Lane when the Indian correspondent brought her here for lunch and she was capitivated. “As you crossed Middlesex St, coming from the City of London, all the windows were smashed and things were desolate.” she recalled, yet for Daniele it was the beginning of a fascination explored through photography which continues until the present day. “I found it interesting that a lot of people would not come and visit me in East London,” she confided to me, “Because it was the first place I found in London with a sense of wonder, a sense of poetry.”

In 1982, Daniele began taking photographs in Brick Lane. It was a time of racial discord in the East End and, working for the GLC Race & Housing Action Team, Daniele employed her photography to record injuries inflicted upon victims of racial assault, the racist graffiti and the damage that was enacted upon the homes of immigrants, the broken windows and the burnt-out flats. “People actually spat at me and shouted at me in the street,” she confessed. Undeterred, Daniele became part of the Bengali community and was called upon to photograph poor living conditions as residents campaigned for better housing – with the outcome that she was also invited to record more joyful occasions too, weddings and community events.

A Californian of French/American ancestry who grew up in Argentina and was taught to ride by a Gaucho, Daniele found herself in her element working at the Spitalfields City Farm for several years where she kept dray horses and rode around the East End in a cart. An experience which afforded the unlikely observation that the lettered fascias on shops and street signs are placed high because they were originally designed to be at eye-level for those sitting in horse-drawn vehicles. Becoming embedded in Spitalfields, Daniele photographed many of the demonstrations and conflicts between Anti-Fascist and Racist groups that happened in Brick Lane, taking pictures for local and national newspapers, as well as building up a body of personal work which traces her intimate relationship with the people here, reflecting the trust and acceptance she won from those whom she met.

George, Nora & the Pigeon Cage – “East Enders who once cared for the ravens at the Tower of London, they soon took to raising racing pigeons for club meetings and competitions.”

Bethnal Green Pensioner – “A delicately-faced woman answered the door when I knocked and talked to me at length about her life, her dreams and her memories…”

Elections – “A group of Bengali women vote in 1992 – when the BNP stood in Tower Hamlets – many for the first time, following a drive made by groups including ‘Women Unite Against Racism.’ This was formed when local women found themselves to be three or four in meetings of over a hundred men and decided that, rather than be patronized as token females, they preferred to reach out to empower and support those women who might not otherwise vote.”

Eva wins the prize – “Eva came from Germany in the fifties, and grew plants and made soups out of what others might consider weeds – nettles, spinach, beet root tops – as well as sewing and embroidering all manners of pillows and textile pieces, from hop-pillows to aid sleep at night to tablecloths in the Richelieu style – and she was always game to show her wares of jams, sewing and plants at local events.”

French waiter in the docklands.

John & John – “This is John Lee, formerly of Spitalfields City Farm, now an organic dairy and pig co-operative farmer in Normandy, and ‘John’ who would often pop in to visit from Brick Lane Market and use the toilet.”

Immigration – “This refers to the moment when individuals of Asian origin in East Africa were told their colonial British passports would be no longer valid after a certain date – thus causing many to come to Britain to establish their rights to nationality, and as a result, many families camped out at the airport waiting to be met.”

Toy Museum Lascars – “a set of nineteenth century figures which represent seamen from a range of ethnicities and cultures who would have once been seen in the docklands.”

Lam at Fire – “Lam who worked for the GLC’s Race and Housing Action Team visits a family of Vietnamese heritage in 1984 in the Isle of Dogs after they were petrol bombed the night before and only saved because the granny awoke and saw smoke. Lam lived as a refugee in Hong Kong, and then in England where he was housed at first in a small village which greeted him with a gift of dog faeces through the letter box. ‘Is it the same in the USA?’ he asked me.”

Minicab – “A traditional minicab sign hovers over a resident whose front door, back door and side doors touched three different boroughs, causing him havoc and much correspondence with council tax officers.”

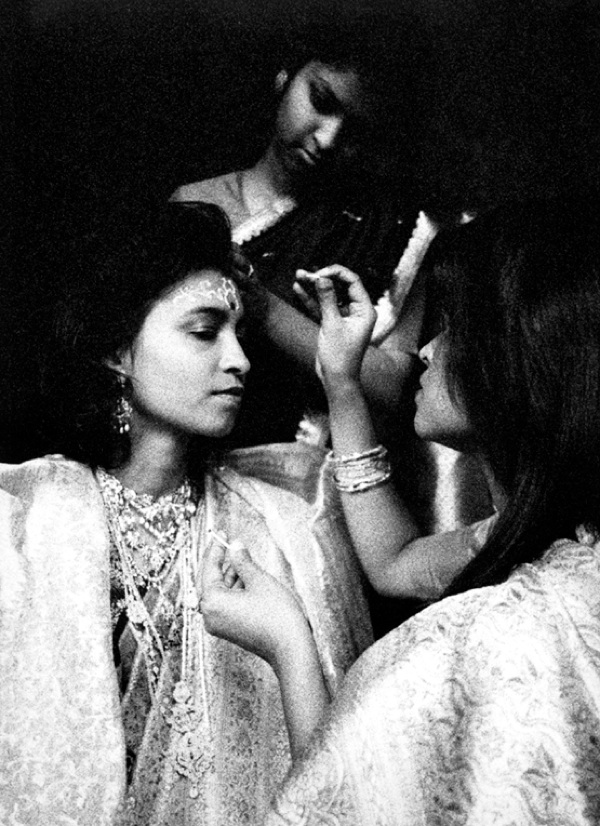

“Noore’s sister-in-law and friends help with wedding preparations, and a spot of toothpaste for intricate designs on her forehead.”

Paula, Woodcarver in her studio.

“Peter’s trades ranged from wheeling an old cart around as a rag & bone man to performing Punch & Judy puppet shows at children’s parties. Furniture and objects of interest flowed through his flat, and overflowed into the courtyard when a boat, which he’d sit in for evening cocktails, wouldn’t fit through the front door….”

Salmon Lane Horses – “A girl and her mother wait for the farrier after returning from school. Stables with horses for work and leisure dotted the streets and yards until developers picked off the remainder of the wasteland and yards where the animals were housed.”

Somali Girl – “This shows one of a group of children playing in a courtyard off Cable St where homes backed onto one another, enabling children to play within sight and ear-reach of parents indoors.”

Vietnamese Baby – “A voluntary sector advocate visits a Vietnamese family to check on their newborn’s progress. Over five hundred Vietnamese children of Chinese origin attended Saturday supplementary school classes at St Paul’s Way School in the eighties and nineties, most from Limehouse and the Isle of Dogs. Many had been housed across Britain but chose to leave the isolation of village homes, offered in a Home Office policy of dispersement, preferring the security of living in the metropolis – sometimes with thirteen family members in two rooms – thereby linking with community networks leading to jobs, further training and more fulfilling lives.”

Members of the Vietnamese Friendship Society.

Lathe, Whitechapel Bell Foundry – “Photographed in the eighties when the Bell Foundry was more a local point of interest, before it grew internationally famous.”

Brick Lane at Night – ” At a time when women were rarely seen on Brick Lane, I was once asked where my ‘friend’ was. I said the person I usually shopped with must be out and about – to which the questioner kindly patted my hand and whispered ‘they always come back…’ Some time passed before it dawned on me that many of the white women accompanying Asian men on the street were ‘working women’….”

Market Cafe Farewell – “Market traders, artists and local characters, ranging from Patrick who directed traffic from the Blackwall Tunnel and Tower Bridge to Commercial St- regardless of whether it flowed without his assistance – all squeezed into this one-room-cafe which opened in the early hours of each morning. Then it vanished one day with only a farewell note left to confirm where it had been.”

Photographs copyright © Daniele Lamarche

Cries Of London Scraps

It is my pleasure to publish these modest Victorian die-cut scraps which are the latest acquisition in my ever-growing collection of the Cries of London. The Costermonger scrap has the name “W. Straker, Ludgate Hill” rubber-stamped on the reverse and – sure enough – by pulling the London Trade Directory for 1880 off the shelf, I found William Straker, Silver & Copperplate Engraver, Printer, Die Sinker, Wholesale Stationer & Stamp Cutter, 49/63 Ludgate Hill. These mass-produced images appeal to me with their vigorous life, portraying their subjects with their mouths wide open enthusiastically crying their wares – all leading players in the drama of street life in nineteenth century London.

Newspaper seller (The Star was published in London from 1788-1960)

Sandwich-board man (Dan Leno started his career in Babes in the Wood at Drury Lane in 1888)

Milkman

Sweep

Watercress seller

Crossing sweeper

Shoe-shine

Buttonhole seller

Costermonger

You can read my feature about William Marshall Craig’s prints of the Cries of London in the September issue of World of Interiors on the newstands now.

You may also like to take a look at these other sets of the Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

More of Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders