Tony Bock At Watney Market

Tony Bock took these pictures of Watney Market while working as a photographer on the East London Advertiser between 1973 and 1978. Within living memory, there had been a thriving street market in Watney St, yet by the late seventies it was blighted by redevelopment and Tony recorded the last stalwarts trading amidst the ruins.

In the nineteenth century, Watney Market had been one of London’s largest markets, rivalling Petticoat Lane. By the turn of the century, there were two hundred stalls and one hundred shops, including an early branch of J.Sainsbury. Tony’s poignant photographs offer a timely reminder of the life of the market that existed before the concrete precinct of today.

Born in Paddington yet brought up in Canada, Tony Bock came back to London after being thrown out of photography school and lived in the East End where his mother’s family originated, before returning to embark on a thirty-year career as a photojournalist at The Toronto Star. Recalling his sojourn in the East End and contemplating his candid portraits of the traders, Tony described the Watney Market he knew.

“I photographed the shopkeepers and market traders in Watney St in the final year, before the last of it was torn down. Joe the Grocer is shown sitting in his shop, which can be seen in a later photograph, being demolished.

In the late seventies, when Lyn – my wife to be – and I, were living in Wapping, Watney Market was our closest street market, just one stop away on the old East London Line. It was already clear that ‘the end was nigh,’ but there were still some stallholders hanging on. My memory is that there were maybe dozen old-timers, but I don’t think I ever counted.

The north end of Watney St had been demolished in the late sixties when a large redevelopment was promised. Yet, not only did it take longer to build than the Olympic Park in Stratford, but a massive tin fence had been erected around the site which cut off access to Commercial Rd. So foot and road traffic was down, as only those living nearby came to the market any more. The neighbourhood had always been closely tied to the river until 1969 when the shutting of the London Docks signalled the change that was coming.

The remaining buildings in Watney St were badly neglected and it was clear they had no future. Most of the flats above the shops were abandoned and there were derelict lots in the terrace which had been there since the blitz. The market stalls were mostly on the north side of what was then a half-abandoned railway viaduct. This was the old London & Blackwall Railway that would be reborn ten years later as the Docklands Light Railway and prompt the redevelopment we see today.

So the traders were trapped. The new shopping precinct had been under construction for years. But where could they go in the meantime? The new precinct would take several more years before it was ready and business on what was left of the street was fading.

Walking through Watney St last year, apart from a few stalls in the precinct, I could see little evidence there was once a great market there. In the seventies, there were a couple of pubs, The Old House At Home and The Lord Nelson, in the midst of the market. Today there are still a few old shops left on the Cable St end of Watney St, but the only remnant I could spot of the market I knew was the sign from The Old House At Home rendered onto the wall of an Asian grocer.

I remember one day Lyn came home, upset about a cat living on the market that had its whiskers cut off. I went straight back to Watney St and found the beautiful tortoiseshell cat hiding under a parked car. When I called her, she came to me without any hesitation and made herself right at home in our flat. Of course, she was pregnant, giving us five lovely kittens and we kept one of them, taking him to Toronto with us.”

Eileen Armstrong, trader in fruit and vegetables

Joe the Grocer

Gladys McGee, poet and member of the Basement Writers’ group, who wrote eloquently of her life in Wapping and Shadwell. Gladys was living around the corner from the market in Cable St at this time.

Joe the Grocer under demolition.

Frames from a contact sheet showing the new shopping precinct.

Photographs copyright © Tony Bock

You may like to see these other photographs by Tony Bock

At The Annual Grimaldi Service

I am publishing my account of a visit to the Annual Grimaldi Service as a reminder to any readers who might choose to join this year’s service which takes place next Sunday 1st February at 3pm at All Saints Church, Livermore Rd, Dalston.

The first Sunday in February is when all the clowns arrive in East London for the annual service to honour Joseph Grimaldi (1778-1837), the greatest British clown – held since 1946 at this time of year, when the clowns traditionally gathered in the capital prior to the start of the Circus touring season. Originally celebrated at St James’ Pentonville Rd, where Grimaldi is buried, the service transferred to Holy Trinity, Dalston in 1959 where the event has grown and grown, and where there is now a shrine to Grimaldi graced with a commemorative stained glass window.

By mistake, I walked into the church hall which served as the changing room to discover myself surrounded by painted faces and multi-coloured suits. Seeing my disorientation, Mr Woo (in a red wig and clutching a balloon dog) kindly stepped over to greet me, explaining that he was veteran of forty years clowning including a stint at Bertram Mills Circus with the legendary Coco the clown – before revealing it was cut short when he fell over and fractured his leg, illustrating the anecdote by lifting his trouser to reveal a savagely-scarred shin bone. “He’s never going to win a knobbly knees contest now!” declared Uncle Colin with alarming levity, Mr Woo’s performing partner in the double act known as The Custard Clowns. “But what did you do?” I enquired in concern, still alarmed by Mr Woo’s injury. “I got a comedy car!” was Mr Woo’s shrill response, accompanied by an unnerving chuckle.

Reeling from the tragic ambiguity of this conversation, I walked around to the church where fans were gathering for the service and there, in the quiet corner church dedicated to Joseph Grimaldi, I had the good fortune to shake hands with Streaky the clown, a skinny veteran of sixty-three years clowning. There is a poignancy to old clowns such as Streaky with face paint applied to wrinkled skin – a quality only emphasised by the disparity between the harsh make-up and the infinite nuance of the lined features beneath.

At first, the presence of the clowns doing their sideshows to warm up the congregation changed the meaning of the sacred space, as if the vaulted arches became tent poles and we had come to a show rather than a church service – although both were strangely reconciled in the atmosphere of celebration that prevailed. Yet although the children delighted in the comedy and the audience laughed at the gags, I must admit that – as I always have – I found the clowns more funny peculiar than funny ha-ha.

But it is precisely this contradiction which draws me to them, because I believe that, through embracing grotesque self-humilation, they expose an essential quality of humanity – that of our innate foolishness, underscored by our tendency to take ourselves too seriously. We need to be startled or even alarmed by their extreme appearance, their gurning and their dopey japes, in order to recognise our true selves. This is the corrective that clowns deliver with a cheesey grin, confronting us with a necessary sense of the ridiculous in life.

“This is the best job I ever had – to make people smile and get them to laugh,” declared Conk the Clown, once he had demonstrated blowing bubbles from his saxophone. “How did you start?” I enquired. “I got divorced,” he replied – and everyone within earshot laughed, except me. “I had depression,” Conk continued with a helpless smirk, “so I joined the amateur dramatics, but I was no good at it, so I thought, ‘I’ll be a clown!'” Twelve years later, Conk has no apparent cause to regret his decision, as his mirthful demeanour confirmed. “It’s something inside, a feeling you know – everyone’s got laughter inside them,” he informed me with a wink, before disappearing up the aisle in a cloud of bubbles pursued by laughing children.

Turning around, I found myself greeted by Glory B, an elegant lady dressed in subtle tones of turquoise and blue, and sporting a huge butterfly upon her hat. Significantly, her face was not painted and she described herself as a ‘Children’s Entertainer’ rather than a ‘Clown.’ “Sometimes children are scared of clowns, ” she admitted, articulating my own thoughts with a smile, “so I work with Mr Woo as a go-between, to comfort them if they are distressed.”

Once the clown organist began to play, everyone took their seats and the parade of clowns commenced – old troupers and young goons, buffoons and funsters, jokers and jesters – enough to delight the most weary eyes and lift the spirits of the most down-hearted February day. An army of clowns filled the church with their pranking and japes, and their high wattage personalities. The intensity of an army of clowns is a presence that defies description, because even at rest there is such bristling potential for misrule.

In their primary-coloured parodic suits, I could recognise the styles of many periods, from both the twentieth and the nineteenth centuries, and when a clown stood up to carry the wreath to lay in honour of ‘Joey Grimaldi,’ I saw he was wearing an eighteenth century clown suit. At the climax of the service, the names of those clowns who had died in the year were read out and, for each one, a child carried a candle down the nave. After the announcements of ‘Sir Norman Wisdom,’ ‘Buddi,’ ‘Bilbo’ and ‘Frosty,’ I saw a feint light travel through the crowd to be lost at the rear of the church and it made tangible the brave purpose of clowning – that of laughing in the face of the darkness which surrounds us.

Mr Woo worked with Coco the clown at Bertram Mills Circus until he fractured his leg

Conk the clown once suffered from depression

Arriving at Holy Trinity, Dalston

Streaky at Grimaldi’s shrine with the case of eggs recording the distinctive make-up of famous clowns

Streaky the clown, a veteran of sixty-three years clowning

Glory B, Children’s Entertainer

The commemorative window for Joseph Grimaldi

You may also like to take a look at

Mattie Faint, Clown & Giggle Doctor

John Claridge’s Clowns (Act One)

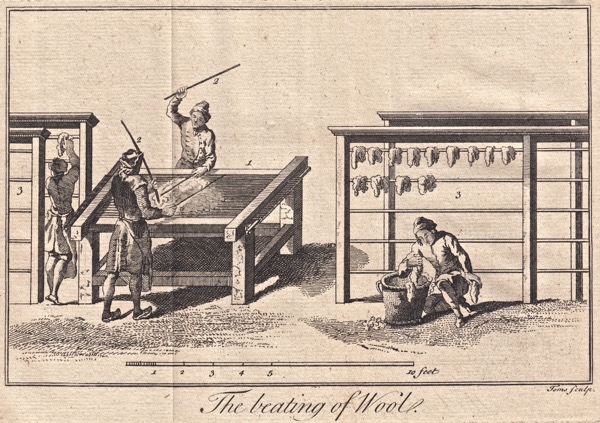

The Principal Operations Of Weaving

These copperplate engravings illustrate The Principal Operations of Weaving reproduced from a book of 1748 in the collection at Dennis Severs House. Many of these activities would have been a familiar sight in Spitalfields three centuries ago.

Ribbon Weaving

Dennis Severs House, 18 Folgate House, Spitalfields, E1

You make also like to read about

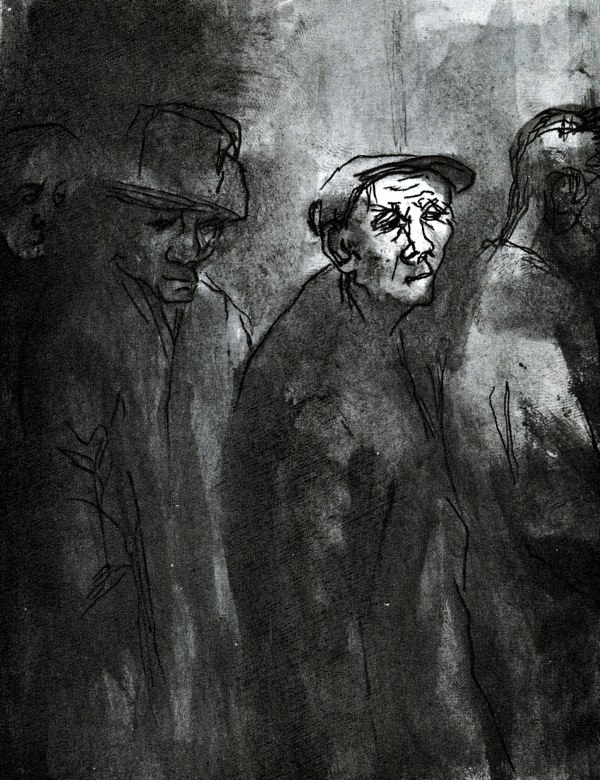

Eva Frankfurther, Artist

There is an unmistakeable melancholic beauty which characterises Eva Frankfurther‘s East End drawings made during her brief working career in the nineteen-fifties. Born into a cultured Jewish family in Berlin in 1930, she escaped to London with her parents in 1939 and studied at St Martin’s School of Art between 1946 and 1952, where she was a contemporary of Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach.

Yet Eva turned her back on the art school scene and moved to Whitechapel, taking menial jobs at Lyons Corner House and then at a sugar refinery, immersing herself in the community she found there. Taking inspiration from Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz and Picasso, Eva set out to portray the lives of working people with compassion and dignity.

In 1959, afflicted with depression, Eva took her own life aged just twenty-eight, but despite the brevity of her career she revealed a significant talent and a perceptive eye for the soulful quality of her fellow East Enders.

“West Indian, Irish, Cypriot and Pakistani immigrants, English whom the Welfare State had passed by, these were the people amongst whom I lived and made some of my best friends. My colleagues and teachers were painters concerned with form and colour, while to me these were only means to an end, the understanding of and commenting on people.” – Eva Frankfurther

Images copyrigh t© Estate of Eva Frankfurter

You may also wish to take a look at

Gillian Tindall’s Lost People

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A COPY FOR £10

Remembering writer and historian Gillian Tindall who died in October, I am publishing her meditation upon the paradox of photography – that brings us closer to history yet also separates us from the past.

Boulevard du Temple, Paris, by Louis Daguerre, 1838

It is over a hundred and fifty years years since photographic portraits ceased to be an exotic rarity and began to make their way into the homes of those with a little money to spare. And it is over a hundred years since the first cinemas opened to show flickering silent movies.

For all the centuries before, nearly all people and places that had gone were lost forever, surviving only in the memories of those who would themselves disappear in turn. As each generation died, another tranche of the past slipped quietly into the vast pool of the irretrievable. The faces of kings and a few others rich or famous enough to be painted from life were preserved. But the vast majority of men and women, however prosperous, however active and handsome, however busy their lives, simply became – as the Bible quietly warns – ‘as if they had never been born’.

The tiny minority whose names survived because their stories were told and re-told were typically portrayed in clothes and circumstances that belonged to the time of telling rather than those of their own date. We are used to seeing Mary the Virgin in medieval dress and Christ garbed something like a travelling friar of the same era. It does not bother us that the Palestinian garments of two thousand years ago may have been rather different.

Similarly, our Elizabethan ancestors, looking back into history, were quite at ease imagining that people had always lived and thought more or less as they did. Actors wore the contemporary clothes of their own time rather than ‘period costume.’ The battle scenes in Macbeth bear more relation to the Wars of the Roses – which in Shakespeare’s childhood would still have been remembered by the old – than they do to the battles of the Scottish usurper of five hundred years earlier. And the famous dinner, at which Macbeth is alarmed by Banquo’s ghost, resembles an Elizabethan social gathering rather than anything credible in a remote Scottish glen in the Dark Ages.

Today, if we have any acquaintance with history, we understand the past – I will not say ‘better’ but ‘differently.’ We know that our ancestors, though ‘just like us’ in some ways, did not speak or even think like us. They feared things we do not fear and were robust-minded in ways that shock us. We know they had different assumptions from us, different moral imperatives and different expectations. They are Philip Larkin’s ‘endless altered people’, forever walking down the church aisle in the same way – yet not quite the same.

Anyone who has seen They Shall Not Grow Old, the World War One documentary – with clips of the era adjusted to modern film-speed, coloured and with a sound-track added – will know what I mean. In one way, these young men brought back to life again, so many of whom did not survive till 1918, are painfully like our own husbands, brothers, sons. Only, they are not. They are preserved in an eternal moment that brings them close just as it keeps us apart from them. So much about them – their clothes, their weapons, their slang, their bad teeth, their boots, their mannerisms – indicate that it is the irretrievable past we are viewing.

Another remastered film came my way recently, of a journey along the Regent’s Canal in its working heyday, interspersed with fleeting views of surrounding streets. No Camden Lock market then, instead barges loaded with timber and hard-core, slowly pacing horses and men shifting crates. But no thumps and bangs, no clopping of hooves or crash of water into locks, for films were silent then. Instead, elegiac music has been added, even over the glimpses of streets full of trams and open-topped buses. Nothing could emphasise more the fact that, since the film was shot in 1924, all the busy people in hats and long coats, glancing curiously at the camera as they hurry pass, must now be dead.

The same is true of many other street photographs that now fascinate us with their juxtaposition of the familiar and the strange. Yet often they do not quite carry the same emotional charge as random shots. Many twentieth century photographers, in this and other countries, have done what sketchers and engravers of street-scenes did before them: they have picked out distinctive street-people – traders, beggars, down-and-outs, well-known local characters – as representative figures. Yet the very fact of being singled out makes these people subtly special.

It is the completely incidental figure, often apparently unaware of the camera, in a picture otherwise taken as a streetscape, that stirs in me the feeling that I really am being offered a brief entry into the past. The blessed Colin O’Brien’s views of Clerkenwell and Hackney in the later decades of the twentieth century are occasionally of this kind. So too are some of the East End scenes of John Claridge, though much of the dereliction he recorded is essentially unpeopled. In just a few shots – a lone man in a mackintosh riding a bicycle though a waste-land, a gaunt-faced workman in a suit looking round warily from his work in a yard – I get the eerie sense of being close to a vanished individual’s reality.

And this is true of the celebrated earliest street photo of all, which was taken by Louis Daguerre from a high window of a Paris boulevard in 1838. The camera’s shutter had to open for a long exposure which renders passing carriages and pedestrians as only faint blurs. Yet clearly visible is one man, because he was standing still to have his boots cleaned. He was the first person ever to be photographed. He did not know it. And we have no idea who he was.

Accident at the junction of Clerkenwell Rd and Farringdon Rd, 1957. Photo by Colin O’Brien

E16, 1982. “He’s going home to his dinner.” Photo by John Claridge

You may also like to read about

The Metropolitan Machinists’ Company Catalogue

In recent years, I have eschewed public transport and become a committed cyclist, so I was delighted to discover this 1896 catalogue for The Metropolitan Machinists’ Co, yet another of the lost trades of Bishopsgate, reproduced courtesy of the Bishopsgate Institute

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Signs Of Life

First Snowdrops in Wapping

Even now, in the depths of Winter, there is plant life stirring. As I travelled around the East End over the past week in the wet and cold, I kept my eyes open for new life and was rewarded for my quest by the precious discoveries that you see here. Fulfilling my need for assurance that we are advancing in our passage through the year, each plant offers undeniable evidence that, although there may be months of winter yet to come, I can look forward to the spring that will arrive before too long.

Hellebores in Shoreditch

Catkins in Bethnal Green

Catkins in Weavers’ Fields

Quince flowers in Spitalfields

Cherry blossom in Museum Gardens

Netteswell House is the oldest dwelling in Bethnal Green

Aconites in King Edward VII Memorial Park in Limehouse

Cherry Blossom near Columbia Rd

Hellebores in Spitalfields

Spring greens at Spitalfields City Farm

The gherkin and the artichoke

Cherry blossom in Itchy Park

Soft fruit cuttings at Spitalfields City Farm

Seedlings at Spitalfields City Farm

Cherry blossom at Christ Church