Alfred Daniels, Painter

Come and see Alfred Daniels’ new painting of the Gramophone Man from Wentworth St at The Artists of Spitalfields Life opening at Ben Pentreath Ltd on Wednesday 7th November.

The Gramophone Man

“I’m not really an East Ender, I’m more of a Bow boy,” asserted Alfred Daniels with characteristic precision of thought, when I enquired of his origin. “My parents left the East End, because they were scared of the doodlebugs and bought this house in 1945,” he explained, as he welcomed me to the generous suburban mansion in Chiswick where he lives today. Greeting me in his pyjamas and dressing gown in the afternoon, no-one could be more at home than Alfred in his studio occupying the former living room of his parents’ house. And yesterday, he was snug in the central heating and just putting the finishing touches to a commission that his dealer was coming to collect at six.

Alfred is at the point in life now where the copyright payments on the resale of works from his sixty year painting career mean he no longer has to struggle. “I’ve done hundreds of things to make a living,” he confessed, rolling his eyes in amusement, “Although my father was a brilliant tailor, he was a dreadful business man so we were on the breadline for most of the nineteen thirties – which was a good thing because we never got fat …” Smiling at his own bravado, Alfred continued painting as he spoke, adding depth to the shadows with a fine brush. “This is the way to make a living,” he declared with a flourish as he placed the brush back in the pot with finality, completing the day’s work and placing the painting to one side, ready to go. “The past is history, the future is a mystery but the present is a gift,” he informed me, as we climbed the stairs to the upstairs kitchen over-looking the garden, to seek a cup of tea.

Alfred had spent the morning making copious notes on his personal history, just it to get it straight for me. “This has been fun,” he admitted, rustling through the handwritten pages. “My grandfather came from Russia in the 1880s, he was called Donyon, and they said, ‘Sounds like Daniels.’ My grandfather on the other side came from Plotska in Poland in the 1880s, he didn’t have a surname so they said ‘Sounds like a good man’ and they called him Goodman. My parents, Sam and Rose, were both born in the 1890s and my mother lived to be ninety-two. I was born in Trellis St in Bow in 1924 and in the early thirties we moved to 145 Bow Rd, next to the railway station. I can still remember the sound of the goods wagons going by at night.

One good thing is, I gave up the Jewish religion and thank goodness for that. It was only when I was twelve and I read about the Hitler problem that I realised I was Jewish. Fortunately, we weren’t religious in my family and we didn’t go to the synagogue. But I went to prepare for my Bar Mitzvah and they tried to harm me with Hebrew. We were taught by these Russians and if you didn’t learn it they bashed you. That put me off religion there and then. Yet when we got outside the Black Shirts were waiting for us in the street, calling ‘Here look, it’s the Jew boys!’ and they wanted to bash me too. Fortunately, I could run fast in those days.

My mother used to do all the shopping in the Roman Rd market. She hated shopping, so she sent me to do it for her in Brick Lane. It was a penny on the tram, there and back. But they all spoke Yiddish and I couldn’t communicate, so I thought, ‘I’d better listen to my grandmother who spoke Yiddish.’ I learnt it from her and it is one of the funniest languages you can imagine.

Although my parents were poor, my Uncle Charlie was rich. He was a commercial artist and my father said to him, ‘The boy wants to learn a craft.’ So Charlie got me a place at Woolwich Polytechnic to learn signwriting but I spent all day trying to sharpen my pencil. Then he took me out of the school and got me a job as a lettering artist at the Lawrence Danes Studio in Chancery Lane. It was wonderful to come up to the city to work, and his nephew befriended me and we went to art shops together to look at art books. We drew out letters and filled them in with Indian Ink, mostly Gill Sans. Typesetters usually got the spacing wrong but if you did it by hand you could get it right. It was all squares, circles and triangles.

When Uncle Charlie started his own studio in Fetter Lane above the Vogue photo studio, he offered me a job at £1 a week. Nobody showed me how to do anything, I worked it out for myself. He got me to do illustrations and comic drawings and retouching of photographs. At night, we went down in the tube stations entertaining people sheltering from the blitz. I played my violin like Django Reinhardt and he played like Stefan Grappelli, and one day we were recorded and ended up on Workers’ Playtime.

I had been doing some still lifes but I wanted to paint the beautiful old shops in Campbell Rd, Bow, so I went to make some sketches and a policeman came up and asked to see my identity card. ‘You can’t do this because we’ve had complaints you’re a spy,’ he said. It was illegal to take photographs during the war, so I sat and absorbed into memory what I saw. And the result came out like a naive or primitive painting. When Herbert Buckley my tutor at Woolwich saw it, he said, ‘Would you like to be a painter? I’ll put you in for the Royal College of Art. To be honest, I should rather have done illustration or lettering. At the Royal College of Art, my tutors included Carel Weight – he said, ‘I’m not interested in art only in pictures.’ – Ruskin Spear – ‘always drunk because of the pain of polio’ – and John Minton – ‘ a lovely man, if only he hadn’t been so mixed up.'”

Alfred was keen to enlist, “I wanted to stop Hitler coming over and stringing me up !” – though he never saw active service, but the discovery of painting and of his signature style as the British Douanier Rousseau stayed with him for the rest of his life. After Alfred left the East End in 1945, he kept coming back to make sketchbooks and do paintings, often of the same subjects – as you see above and below, with two images of the Gramophone man in Wentworth St painted fifty years apart.

With natural generosity of spirit, Alfred Daniels told me, “Making a painting is like baking a cake, one slice is for you but the rest is for everyone else.”

The Gramophone Man in Wentworth St, 1950

Sketchbook pages – Cable St, April 1964.

Sketchbook pages – Old Montague St, March 1964.

Sketchbook pages – Hessel St, April 1964.

Sketchbook pages – Old Montague St & Davenant St, March 1964.

Sketchbook pages – Fruit Seller in Hessel St, March 1964.

Leadenhall Market, drawing, 2008.

Billingsgate Market.

Tower Bridge, 2008.

The Royl Exchange, 2008.

Crossing London Bridge, 2008.

In Alfred’s studio

Alfred Daniels, Artist

You may also like to read about

Robson Cezar, King Of The Bottletops

Come and see Robson Cezar’s bottletop pictures at The Artists of Spitalfields Life opening at Ben Pentreath Ltd on Wednesday 7th November.

If you are a regular in the pubs around Spitalfields, you may have noticed a man come in to collect bottletops from behind the bar and then leave again with a broad smile, clutching a fat plastic bag of them with as much delight as if he were carrying off a fortune in gold coins. This enigmatic individual with the passion for hoarding bottletops is Brazilian artist and Spitalfields resident Robson Cezar, and he needs to collect thousands because he makes breathtakingly intricate pictures with them.

Each day, Robson cycles from Spitalfields down to his studio at Tower Bridge where he delights to store his vast trove – the king of bottletops in his counting house – spending endless hours sorting them lovingly into colours and designs to organise his finds as the raw material for his very particular art. An art which transforms these ill-considered objects into works of delicacy and finesse, contrived with sly humour, and playing upon their subtle abstract qualities of colour and contrast.

It all started a couple of years ago, when he asked Sandra Esqulant at The Golden Heart in Commercial St to collect her bottletops for him. For months she gathered them conscientiously and it gave Robson the perfect excuse to drop in regularly. And last year, I showed you some smaller pictures he made, but over this last Winter Robson has begun creating larger, more elaborate bottletop works. As a consequence, Robson often sets out now to visit several bars each night to collect the harvest of bottletops which he needs, that is obligingly – if incidentally – created by the thirsty boozers of our neighbourhood.

And in return for the patronage of getting their bottletops, Robson makes pictures for the pubs. At first he made a golden heart in bottletops as a personal gift for Sandra, but when The Bell in Middlesex St offered him the opportunity to cover the exterior of the pub with bottletops, he seized the opportunity to do something more ambitious. Using over six thousand bottletops, and subtly referencing the colours of the red brick and the green ceramic tiles, Robson has contrived a means to unify the exterior of the building and render it afresh as a landmark with his witty texts. And since they were installed last year, people smile and stop in Middlesex St to take photographs when they catch sight of Robson’s bottletop panels on The Bell. With such eye-catching street appeal, Robson’s work is a natural complement to Ben Eine’s alphabet that he painted on all the shutters along this street last year.

A week ago, Robson’s latest picture was installed at the Carpenters Arms in Cheshire St where landlords Eric & Nigel have been obligingly collecting bottletops for over a year. Hung up on the roof beam in the bar, this is in a different vein from Robson’s works at The Golden Heart and The Bell – creating a stir among the regulars, who are puzzling over the choice of phrase SCREAM PARTNERS for the CARPENTERS ARMS. Go round to take a look yourself and if cannot work it out at once, then a couple of drinks will increase your powers of lateral thinking.

Robson Cezar came to Spitalfields in the footsteps of fellow Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica, who along with Caetano Veloso was one of the many Brazilian cultural exiles in London in the nineteen sixties. Oiticia staged an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1967, introducing the new cultural movement of Tropicalia to Europe by recreating a favela in the gallery. And now Robson is creating his own Tropicalia here in the twenty-first century, reinventing this poverty aesthetic with a pop exuberance that reflects the cosmopolitanism of his own life experience – which began in a favela in Brazil and took him on a journey from South to North America and eventually to Europe, where he found his home in the East End of London.

Combining the sensibility of a fine artist with the painstaking technique of a folk artist, Robson’s bottletop pictures are egalitarian in nature yet sophisticated in intent. They look like signs but they are not signs, or rather they are pictures pretending to be signs. Their exquisite technique and colouration is a crazy joke in contrast to the misrule engendered by the volume of alcohol imbibed to produce this number of bottletops. Yet the lush shimmering beauty of Robson Cezar’s work enchants us with all the bottletops that litter our streets disregarded, and reminds us of all the other pitiful wonders of human ingenuity that we forget to notice.

At the Bell in Middlesex St.

At the Carpenters Arms, Cheshire St.

Why SCREAM PARTNERS at the CARPENTERS ARMS?

Portraits of Robson Cezar in his studio copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Artworks copyright © Robson Cezar

James Brown at Gardners Market Sundriesmen

Come and see James Brown’s Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen print at The Artists of Spitalfields Life opening at Ben Pentreath Ltd on Wednesday 7th November.

This is illustrator & printmaker, James Brown, presenting Paul Gardner, the fourth generation paper bag seller, with a copy of the beautiful print he has created to celebrate this beloved and historic Spitalfields institution, Gardners Market Sundriesmen. When a one hundred and forty year old business advertises for the first time, something special is required and – working in collaboration with Paul – James has contrived a paper bag printed in gold and emblazoned with symbols of all the different items to be purchased at Gardners.

“Knowing about Paul and his story through Spitalfields Life, I thought it would be great to produce a design that he could use as a promotional flyer and that I could also make into a nice limited edition print too,” explained James shyly, standing in front of Paul and aware of the huge departure this first piece of advertising represents for Gardners.

Through supplying the bags, in this area traditionally occupied with small shops and markets, Gardners is naturally the epicentre. Yet with new people coming to set up stalls and open shops all the time, James’ beautiful postcards of his print constitute an ideal introduction to this uniquely appealing shop that will sell you as few bags as you need. James & I distributed the cards in shops and markets on Paul’s behalf, but you can pick up some yourself direct from Gardners Market Sundriesmen in Commercial St and take the opportunity to admire the limited edition print at The Artists of Spitalfields Life exhibition in Bloomsbury next week.

“Paul has so many stories to tell, my visits to Gardners were always lengthy and lively.” confided James, savouring the year it has take to develop his design. “It’s been great to get to know Paul and I really hope the flyer works for him, he is a lovely guy and offers a level of service that cannot be surpassed by any of the online bag and sundries suppliers.”

When I first met James Brown a couple of years ago, he had just quit a ten year career as a textile designer and struck out anew as an illustrator and printmaker, sharing a studio with his brother in Hackney Wick. Since then, I have been delighted to see his bravura designs turning up all over the place. “It’s snowballed really,” he admitted with a private smile of satisfaction, “And now I am making a living at it – exactly what I wanted to do and it’s brilliant!”

James’ screenprint celebrating Gardners Market Sundriesmen, Spitalfields’ oldest family business.

James’ screenprint celebrating Gardners Market Sundriesmen, Spitalfields’ oldest family business.

You may also like to read about

Paul Bommer & The Great Fire Of London

Come and see Paul Bommer’s series of forty-eight delft tiles inspired The Great Fire of London 1666 at The Artists of Spitalfields Life opening at Ben Pentreath Ltd on Wednesday 7th November

Like Pieter Breughel, George Cruickshank and Ronald Searle, Paul Bommer’s work is firmly rooted in the European grotesque and populated with distinctive specimens of humanity – conjured into being through his unique quality of line, waggish, calligraphic and lyrical by turns. Fascinated by culture and lore, Paul celebrates the strange stories that interweave to create social identity and the fabric of history, turning his attention to The Great Fire Of London in this latest series of limited edition Delft tiles.

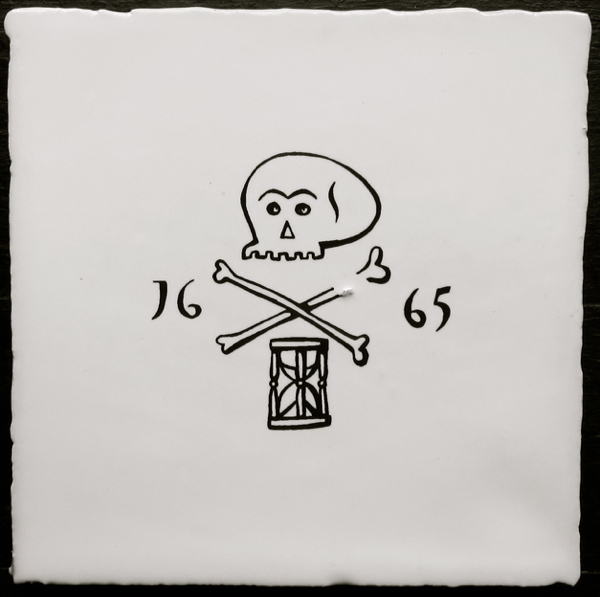

Pest Doctor 1665

Annus Mirabilis 1666

King Charles II

Pudding Lane

Poultry

Fish St Hill

Cock Lane

Eurus – The East Wind, that blew the Fire towards St Pauls.

Hare Court

Windmill

Fig Tree Court

Mister Punch – first recorded in Pepys diary

Smithfield Market

Samuel Pepys

Memento Mori of the Plague

Tiles copyright © Paul Bommer

You may also like to take a look at

Paul Bommer’s Cockney Alphabet

Paul Bommer & Christopher Smart & His Cat Jeoffry

The Artists Of Spitalfields Life

Ben Pentreath Ltd, 17 Rugby Street, Bloomsbury, WC1N 3QT

During the next week, leading up to the opening, I shall be publishing the stories of the artists featured in the exhibition.

Ruminations of a Ghost Hunter

At Halloween, it is my pleasure welcome this guest post from Roger Clarke, the Paranormalist of Shoreditch and author of A Natural History of Ghosts published tomorrow by Penguin.

Ye Olde Axe by Julie Cook

Last Saturday, 27th October, the Fortean Society held a Ghosts Conference at the Bishopsgate Institute and, in between lectures on ‘Ghosts in London’s Hospitals and Theatres’ and ‘Ghosts of the Senate House,’ I attempted to access some nineteenth century trades directories housed there. My friend and now host, The Gentle Author, no stranger to the building – indeed, known to haunt it – had suggested I research there in my quest to find out more concerning an intriguing Shoreditch figure, Georgiana Eagle. She was christened at St Leonard’s Church and her grandfather was a Shoreditch publican of Huguenot descent. I was trying to find out which pub. Was it one of the ‘lost’ haunted pubs of Shoreditch – Ye Olde Axe or the Nag’s Head on Hackney Rd, for example?

I had come across the name of Georgiana Eagle while researching my book A Natural History of Ghosts, and as a Shoreditch resident myself, I was naturally intrigued by her. Dalston was a Victorian nexus of young female psychics including the infamous Florence Cook in the eighteen seventies, and there was a very famous Dalston spiritualist group at the time many of whose members worked on the railways – two recently-built spurs (now the Overground) had opened up the area and were apparently instrumental in making Dalston popular for séances. It was a new area, opening new doors into the other world. However it seems an even younger East London psychic proceeded Miss Cook by several decades amongst the furniture-making factories and leather-working rooms of Shoreditch.

For many years, until 1963 in fact, a gold watch that was displayed in the College of Psychic Studies in Kensington was linked to Georgina Eagle. Known colloquially as ‘Vicky’s Ticker’ it had sported the following inscription ‘Presented by Her Majesty to Miss Georgina Eagle for her Meritorious and Extraordinary Clairvoyance produced at Osborn [sic] House, Isle of Wight, July 15th, 1846.’ It seems it had been bought by the famous newspaperman and even more famous Titanic victim W.T.Stead, and donated to the medium Etta Wriedt precisely because she was known to channel the imperious voice of the late queen.

It has been a holy grail amongst biographers of Queen Victoria to find the mediums the grieving queen might have consulted after the death of Prince Albert but, surprisingly, there is absolutely no evidence she ever consulted one. At first glance, this mysterious watch seemed to suggest otherwise though after a little research it soon emerged there were always, frankly, insurmountable problems with its authenticity. The name of Osbourne House was misspelled. The date predates the demise of Albert and also the advent of the London séance fashion by several years. It also turns out that little Georgiana’s father was a quite well-known stage magician called Barney Eagle.

In fact, little Georgiana did a double-act with her father, a mind-reading trick still in use today, and travelled round the country to local theatres and fairs. Though Eagle was not a conjuror of the first rank, he seemingly had a great gift for self-promotion and made hay with a public spat with another, much more famous, magician named John Henry Anderson. According to the magic historian Charles Waller ‘Of all of Anderson’s imitators, he was the most impudent…he stole Anderson’s tricks, copied his patter, and exactly produced his programme and billing matter’. Also 1846, the date on the watch when Georgiana was only eleven years old, was also the date he published his ‘Barnado’s Book of Magic’. Young Georgiana was billed by her father as ‘The Mysterious Lady,’ and members of the audience were invited to blindfold her in an ‘unmasking of clairvoyance’ (according to the Yorskhireman in December of that year).

Was the watch, which was stolen in 1963 and has never been since, simply a bit of promotional kit used by Barney Eagle to get attention for his book and his mind-reading act in 1846? Or did he add an inscription later? More likely, either Stead or Wriedt added the inscription after hearing a garbled version of the story – and that her act, for from professing to be of clairvoyance, was in fact a bit of flagged up vaudevillian fun.

As early as 1843, Eagle describes himself as an ‘ambidextrous prestidigitator to Her Majesty the Queen’ and adopted such colourful stage names as ‘The Napoleon of Wizards’ and ‘The Royal Wizard of the South.’ His insistence on some kind of royal connection over many years does suggest that at some point a member of the royal family witnessed one of his shows and that this was his main calling card. He died onstage in a Guernsey Temperance Hall in 1858, leaving his store of stage props and tricks to Georgiana, who only fitfully used them over the following years as her three husbands came and went – a photographer, a music professor and a finally a draper twenty-five years her junior. In 1873 in Cheltenham, she was billed as the ‘World Famed Wizard Queen, Humourist and Clairvoyant Mesmerist.’ Vicky’s Ticker seems certain to have been amongst her effects when she died in 1911, since that is the year it ends up with the mediums of Kensington.

It isn’t clear from these later bills whether this Shoreditch girl was now passing herself off as a real medium, and stranger things have been known in the annals of mediumistic practice. Her professional mention of humour seems however to suggest a quality usually lacking in the world of the Victorian Spiritualist, a little levity, and it must be seen as an irony she should end up role-reversed after death, co-opted and contained by the professional organisation of the very people she was actually debunking. As it happens, the library section which listed publicans of the era was closed for lunch and I never had time to go back, after getting sucked in to a talk on the Enfield Poltergeist. I like to think of her in one of the more freighted pubs of the area, perhaps at Ye Olde Axe which, though opposite the church where she was christened, is now a strip joint with an unfairly beautiful exterior. I see it every day from my house, where I wrote my ghost book, with its forlorn, stopped clock.

According to Guy Lyon Playfair – the main investigator of the Enfield Poltergeist – in his Haunted Pub Guide – ‘In 1979, a team of workmen spent nine weeks renovating Ye Olde Axe, which had been derelict for twenty-five years and had enjoyed a fairly unsavoury reputation before that’. Whilst the workmen were digging out foundations for a new fire escape, they found the skeletal remains of two people, including their legs and skulls. The bodies were buried in a trench two foot deep, along with a pair of rusty scissors.

The workmen had stayed overnight onsite in the somewhat derelict building. Playfair tells the story of one of these, one David Simcoe. ‘I’m a light sleeper,’ he said, ‘and one evening we heard quite a lot of noise and thought one of our mates had come into the room where we were sleeping.’ The next morning, they learned that he had been sound asleep before they had gone to bed. The following night, the men put a plank against their bedroom door. In the morning the plank was down and the door was open. This, said Simcoe, was just one of several strange things that had happened while he had been there. I have a feeling that we can expect more of this kind of thing, in view of this pub’s history.

St Leonard’s Church where Georgina Eagle, World-Famed Wizard Queen, Humourist and Clairvoyant Mesmerist, was baptised.

Ye Olde Axe where the mysterious skeletal remains were discovered, buried with a pair of rusty scissors.

Dalston became a nexus for female psychics in the eighteen seventies due to improved transport links.

Georgina Eagle commonly performed under the stage name of Madame Gilliland Card.

Photograph of Ye Olde Axe copyright © Julie Cook

Playbill © British Library

You may also like to read about

Bill Crome, the Spitalfields Window Cleaner who sees Apparitions

Cecile Moss of Old Montague St

Cecile aged four

Although Cecile Moss lived in Old Montague St for fourteen years, this is the only photograph taken of her in Spitalfields, and it was taken for a precise purpose. A photographer came round to take it in 1955, the year Cecile arrived from Jamaica aged four years old, and the picture was sent back to her family in the Caribbean as evidence that she was attending a proper Catholic school with a smart uniform and therefore all was well in London. Yet in contrast to the image of middle class respectability which Cecile’s mother strove to maintain, the family lived together in one room in a tenement and the reason there are no other photographs is because they had no money for a camera.

Almost no trace survives today of the Old Montague St that Cecile knew – a busy thoroughfare crowded with diverse life, filled with slum dwelllings, punctuated by a bomb site and a sugar factory, and lined with small shops and cafes. There, long-established Jewish traders sat alongside dodgy coffees bars in which Maltese, Somalis, Caribbeans and others congregated to do illicit business. In fact, Old Montague St offered a rich and stimulating playground to a young child filled with wonder and curiosity, as Cecile was.

The novel presence of black people proved a challenge to many East Enders at that time. “Sometimes, they knotted their handkerchiefs when they saw me,” recalled Cecile with mixed emotion, “and they’d say, ‘If you see a black person that’s good luck.'” Fortunately, Cecile’s mother’s professional status as a teacher proved to be an unexpected boost to Cecile in this new society and later Cecile became a teacher herself, an occupation that she pursues today from her home in New Cross Gate where she lives with her children and grandchildren. “Since the new overground train, I’ve spent a lot more time in the East End and I still have a lot of friends there.” she admitted to me when I visited her last week, “As you grow older, you tend to want to go back to your home.”

“We came to England from Jamaica in 1955, me, my sister Clorine and my mother, Marlene Moss, to Old Montague St in Spitalfields. She left my father and came over to live with her sister, Daisy. I was four years old and I didn’t know I was coming to England, I was traumatised. But I remember what I was wearing, I wore a double-breasted coat with a velvet Peter Pan collar and lace-up shoes. My mother was a teacher in Jamaica and she didn’t want us to look like refugees arriving in England. The voyage lasted ten days and we were met by my uncle at Southampton. It was very confined on the boat so that when I got off, I kept on running around.

We lived in a building where the Spitalfields health centre is today. We were 9b, above a shop where two elderly Jewish sisters lived. My mother cried for days because we had to share one toilet with three other floors, so it was really quite disgusting. I was told that I had come to get a doll. But it was an ugly chalky-skinned blond doll, and I was so angry and upset that I threw it away and smashed it, which made my aunt think I was a very ungrateful little girl. My mother,my sister and I all lived in one room. My sister was eleven and she remained silent, whereas my mum and I just cried a lot. I missed my family in Jamaica.

Because we were Catholics, we went to St Anne’s Catholic church and mother got talking to the priest. He told her she could teach in St Gregory, a Secondary Modern in Wood Close, doing supply work. When she started at the school she was shocked. One of the pupils was absent from the register and they said, ‘He’s gone down for GBH.’ My mother came back and asked my aunt, ‘What is this GBH?’ She said she was going introduce Shakespeare to the school but they said,‘We don’t want you bringing any of your kind of rubbish here!’

I went to St Patrick’s school around the back of St Anne’s and my sister, because she had already passed the eleven-plus, went to Our Lady’s convent in Stamford Hill. Yet I only lasted two weeks at St Patrick’s because the kids hit me and pushed me over. I can’t remember if they called me racist names, but I know I was terribly unhappy. My mother took me away and sent me to Stamford Hill too. I was five years old, and she put me on the 653 bus and told the conductor where to let me off. The people on the bus would look after me and I never missed my stop. I felt safe. So we lived in the East End but we went to school in North London. That was unusual but, because my mother was a teacher, we were middle class, even though we lived in Old Montague St which was a slum. Old Montague St had quite a reputation for drugs. There were dark tenements with dark passages with dark dealings.

When my mum got a permanent job at St Agnes’ school in Bow, she took me away from Our Lady’s at seven years old. So I never went back to school in Spitalfields but I used to play out on the street a lot. Most of the children I played with were second generation Irish with names like Touhy, O’Shea, Latimer and Daley – that’s who I grew up with. There was an older Irish boy who looked out for me, he said I was part of the gang. He told us we mustn’t speak to the people on Brick Lane because they were Jewish. He was looked after by his grandmother. She was a character. Every Saturday night, she went to the pub on the corner of Chicksand St and filled a jug with port or whatever and stumbled back singing, ‘Daisy, Daisy give me your answer do.’ And my mother cried and said, ‘Look what we have come down to.’ One day, the old lady, she tied a skipping rope across the street to stop the traffic so that we could play. When the police came along, she said, ‘The children have got nowhere to play.’ And we were all shocked, but later they opened a playground on the corner of Old Montague St and Vallance Rd.

I loved going to Petticoat Lane. Every Friday, my aunt would go and get a chicken – you could choose one and they would kill it for you. There were street entertainers, an organ grinder and man who lay on a bed of hot coals. Walking up Wentworth St, there were all Jewish shops with barrels of pickles and olives outside. I was fascinated but my mother said, ‘That’s not our food.’ A lot of the stallholders were quite friendly to me and my mother because they thought we were the next wave of immigrants. There was a cafe I walked past with my mum, it was full of black-skinned men but I couldn’t understand what they were saying even though they were like us. They were Somalis. The men outside, they’d give me sixpence and put me on their knee. They liked to see me because they were away from their own children. I think we were some of the first West Indians here, there were no other black kids.

I spent a lot of time in the fleapit cinema on Brick Lane on Saturdays. But by the time I turned seven, my mum stopped me playing out. She forbade me, so my wanderings around Spitalfields stopped and I don’t mix with the kids on the street anymore. Instead I became more friendly with the kids I was at school with in Bow.

My aunt Daisy went back to Jamaica and my sister returned when she was eighteen. So it was just me and my mum in the end. We shared a bedroom and we had a sitting room, with the kitchen in the hallway. I was very embarrassed about where I lived and I didn’t bring friends home because it was a slum. All this time, my mother was not divorced, she was still married and it really held her back. She even had to ask a friend to his name down for her to be able to buy a television.

There was a hardware shop and other shops run by Jewish people, where they got on well with my mother. There was a bit of snobbishness because she was a teacher. It used to cushion me too, I was Mrs Moss’ daughter. When she complained, they used to say to her, ‘Never mind, we had it, now it’s your turn.’ Referring the racial prejudice, they meant it was something you put up with, then it would pass. And by the time I left Spitalfields, it was the Bengalis coming in, so it was quite profound what they said – it was a rite of passage at that time.

When I was eighteen, we moved out. Looking back on it, I’ve got to say it was a happy time. I knew when I’d forgotten Jamaica and made my transition to England. I played a lot on the stairs and I pretended to have a ‘post office’ there. One day my mother was there too, washing some clothes on the landing and she corrected my speech. ‘It’s not ‘spag-ETTEE,” she said, ‘It’s ‘spaghetti” And, I realised then, that was because I’d left Jamaica behind and I spoke Cockney.

Today I often teach immigrants, children for whom English is their second language, and I can say to them, ‘I know what you are going through.'”

Old Montague St 1965 by Geoffrey Fletcher

Cecile Moss