Yet More Drypoint Etchings By Peta Bridle

This week Peta Bridle sent me her latest additions to the growing portfolio of drypoint etchings she has been working on for more than year, many inspired by stories and characters from the pages of Spitalfields Life.

Gary Arber, W F Arber & Co Ltd – On 28th May, Gary closes the print shop opened by his grandfather Walter in 1897 – “Gary is stood next to a Golding Jobber which he told me was used to print handbills for the suffragettes. On his right stands a Supermatic machine and, behind him in the corner, is a Heidelberg which he filled with paper to show me how it worked. The whole room was a confusion of boxes and paper with the odd tin toy thrown in, and lots of string hanging from the ceiling. I feel privileged to have been invited downstairs to make this record of his print shop.”

Spoons by Barn The Spoon – “From left to right: A cooking spoon. A spoon of medieval design. A spoon based on a Roma Gypsy design. The small spoon in the centre is a sugar spoon. A shovel. The large spoon on the right is a Roman ladle spoon. Barn told me the word ‘Spon’ which is carved on the handle is an old Norse word which means ‘chip of wood.’”

Leila’s Shop, Calvert Avenue “- I love visiting Leila’s Shop throughout the year to discover the fresh vegetables of every season, straight from the field and piled up in mouth-watering displays.”

Donovan Bros, Crispin St – “Although it is not a shop anymore I believe Donovan Bros are still producing packaging. I like the muted colours the shop front has been painted and wonder what the shop would have looked like inside?”

Borough Market, London Bridge – “This is the view overlooking Borough Market, looking from the top of Southwark Cathedral tower. The views of London from up there are beautiful but I don’t like the height too much!”

Clerk’s Cootage, Higham – “Charles Dickens based some of Great Expectations around the north Kent marshes and, if you were to travel past this fifteenth century cottage to the end of the road and turn right and carry on through the village of Higham, you would arrive at Gads Hill Place, his former home. If you were to turn left from the road beyond Clerk’s Cottage, you would reach St. Mary’s Church where Katey Dickens married Charles Collins, brother of Wilkie Collins.

Wapping Old Stairs – “To reach the stairs you have a to go along a tiny passage to the side of the Town of Ramsgate. Originally, the stairs were a ferry point for people wishing to catch a boat along the river. I think they are quite beautiful and I like to see the marks of the masons’ tools, still left on the stones after all this time.”

The Widow’s Son, Bow – “The landlady stands holding a hot cross bun in front of a large glass Victorian mirror with the pub name etched onto it. Every Good Friday, they have a custom where a sailor adds a new bun in a net hanging over the bar to celebrate the widow who once lived here, who made her drowned sailor son a hot cross bun each Easter in remembrance.”

E.Pellicci, Bethnal Green Rd. “Nevio Pellicci kindly allowed me to make a couple of visits to take pictures as reference to create this etching. It was at Christmas time and after they closed for the afternoon. Daisy my daughter is sitting in the corner.”

Paul Gardner at Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen, Commercial St. “I did buy a few bags off Paul whilst I was there!”

Tanya Peixoto at bookartbookshop, Pitfield St. “I am friends with Tanya who runs this shop and she has stocked my homemade books in the past.”

Des at Des & Lorraine’s Junk Shop, Bacon St. “An amazing place that I want to re-visit since I never got to look round it properly …”

Liverpool St Station

Prints copyright © Peta Bridle

Nicholas Borden’s Winter Paintings

Junction of Vallance Rd & Three Colts Lane (Click to enlarge)

This new picture by Nicholas Borden from last Winter shows the exact spot I first met him in Vallance Rd, painting in the snow, over a year ago. Since then, Nicholas has been extraordinarily productive with two successful shows in Spitalfields and another coming up at the Millinery Works in Islington in the Summer. “When I began, I was at a low point and I needed to help myself, that’s all it was – I didn’t have an audience,” he admitted to me, “but now I have a lot more confidence in my work, it’s allowed me to look at what I do seriously and realise there is a future in it.”

Now we can say for certain that Winter is over, it is possible to take a look back at the oil paintings Nicholas has achieved, working outside while the rest of us were huddled by the fire. “I spend as many days as I can out on the street, if the weather allows I am out seven days a week,” he assured me, “but I can’t work for more than several hours at a time.” Hardy by nature and an experienced fisherman, Nicholas is not discouraged by the weather as these dozen paintings testify. In fact, he is a connoisseur of our cloudy Northern skies which overarch most of his canvasses.

“I’ve always known I wanted to do this,” Nicholas confessed to me as he contemplated his new paintings in modest satisfaction, “but it’s not a social reflex, I don’t have a political agenda – I just feel a compulsion to record what’s around me.”

Shoreditch High St (Click to enlarge)

Mare St (Click to enlarge)

Crescent on Essex Rd (Click to enlarge)

Morning Lane, Hackney (Click to enlarge)

Kings Cross Rd (Click to enlarge)

Kings Cross Station (Click to enlarge)

St Pancras Station

St Pancras Hotel

Covent Garden Underground Station

Charlton Place, Islington

Barbican Towers – work-in-progress

Nicholas Borden

Paintings copyright © Nicholas Borden

You may like to take a look at more of Nicholas Borden’s work

Adam Dant’s London Bestiary

Adam Dant has been at work over Easter to create this splendid portfolio of chiaroscuro wood cuts of Ten Creatures of London Legend which make their debut with TAG Fine Arts at the London Original Print Fair that runs at the Royal Academy from tomorrow until Sunday. In the sprit of Hogarth, you can buy a customised woodcut ticket from Adam for £20 and get a chance to win one of two sets of these prints being raffled.

The Vegetable Lamb Of Tartary, Lambeth Palace

This was believed to be a sheep grown on a plant from a melon-like seed. Introduced to England by Sir John Mandeville in the fourteenth century, an example of this legendary zoophyte can be found at Lambeth Palace.

The City Of London Dragon, Chancery Lane

The dragon guards the boundary of the City of London and its design is based upon a seven-foot-high original created by J B Bunning in 1849, upon the roof of the former Coal Exchange in Lower Thames St.

The Werewolf Of London, Guys Hospital

In 1963, Dr John Illis of Guys Hospital wrote a paper On Porphyria & Aetiology Of Werewolves, arguing that red teeth, photosensitivity and psychosis experienced by those suffering of Porphyria may have been the characteristics that led to them being mistaken for werewolves.

The Enlightenment Merman, British Museum

Part-monkey and part-fish, the Merman was ‘caught’ in Japan in the eighteenth century and given to Queen Victoria’s virtuous grandson Prince Arthur who donated the desiccated creature to the British Museum, where it may be found today in the Enlightenment Gallery.

The Olympic Park Monster Catfish, Stratford

In December 2011, a Canada Goose was dragged beneath the waters of the River Lea by an unseen predator believed to be a Monster Catfish known to locals as ‘Darren.’

The Sheep Having A Monstrous Horn, Royal Society

This animal from Devonshire gained fame in the capital having been presented to the Royal Society on account of a giant twenty-six inch horn which grew from its neck.

Old Martin, Martin Tower At The Tower Of London

Old Martin, the phantom bear of the Tower of London’s Martin Tower is reported to have scared one unfortunate beefeater to death. A bear by the name of Old Martin was given to George III by the Hudson Bay Company in 1811 when the Tower had its own menagerie.

Spring-Heeled Jack, Bearbinder Rd In Mile End

Numerous sightings of a violent demonic creature with supernatural abilities at jumping terrorised people in the East End in 1838.

The Phantom Chicken, Pond Sq Highgate

The half-plucked Chicken, which was seen most recently in 1970 by a caressing couple, is said to be the same chicken which Sir Francis Bacon had attempted to pack with ice in 1626 during an early experiment in freezing food that resulted in the philosopher’s death from Pneumonia.

Twelve Foot Fossilised Irish Giant, Broad St Station

Weighing two tons and fifteen hundredweight and standing twelve feet two inches tall, the fossilised ‘Irish Giant’ disappeared from Broad St Station in 1876 after being dug up by a Mr Dyer in County Antrim and toured around Liverpool and Manchester.

Images copyright © Adam Dant

Email Adamdant@gmail.com to buy a customised woodcut ticket for £20 for a chance to win one of two sets of woodcut prints of Ten Creatures Of London Legend being raffled.

Greengrocers & Hardware In Aldersgate

Aldersgate takes its name from one of the ancient gateways to the City of London that formerly divided the street into “within” and “without.” Here Shakespeare once owned property and, in later days, John Wesley had a religious experience which led to the founding of Methodism.

Yet Aldersgate does not declare its history readily, dominated now by the Barbican and Golden Lane Estates. Although Crescent House still harbours a string of independent shops which tell their own modest story of the family businesses that have lined this street for centuries – as Contributing Photographer Patricia Niven & I found out when we went calling recently.

John Horwood, Greengrocer

“My dad Harry, his old shop used to be opposite Barbican Underground station,” explained John, “He got moved out in 1964, when they were building the Barbican, and he opened up here in Crescent House in 1965 – but William, my grandfather, he had a shop before that in Goswell Rd.”

John was standing amidst a fine array of high-quality fruit and vegetables that testify to the three generations of experience which lie behind him and also to his nightly visits to Covent Garden Market, topping up the stock daily to keep everything fresh. Mystified why people visit the supermarkets that surround him to buy inferior produce at higher prices, John is proud that he has kept faith in the trade he grew up in. It is a matter of honour for him. Consequently, John has loyal customers who once visited his father’s shop and still buy their vegetables from John regularly today, including several retired nurses from St Bart’s Hospital who live locally – one of whom, Nancy, is ninety-six.

“Five nights a week, I get up at quarter past one and and I am at the market by quarter to two, then I get back here around five thirty and. after preparation, I am ready to open at eight,” he admitted to me proudly, “In the past, this shop had five or six people in it but now there’s just me.”

John’s greengrocer’s shop is one of the most appealing I have visited, not for the overtly demonstrative nature of his displays but because everything is chosen and arranged with such care and attention. “I attempt to find the best and I have a big range of fruit,” he assured me with twinkly eyes and quiet enthusiasm, ” I have artichokes and chicory at present, which are very popular with the Italian travel agents across the road.”

These days, John supplements his business by selling a splendid variety of plants alongside clay flowerpots, watering cans and compost, fulfilling the demand from residents of surrounding flats who cultivate window boxes and pot plants upon their sills. So, if you are in Aldersgate, I urge you to seek out John Horwood, a dignified professional and the last of the gentleman grocers in this corner of London.

Marc, Peter, Betty, Paul & Simon Benscher, three generations in hardware

If you were of the Do-It -Yourself frame of mind and you walked into City Hardware in Aldersgate, then you might have an experience of religious intensity – comparable with that of John Wesley three centuries ago – in response to the mind-boggling range of ironmongery that may be obtained here, supplied by the Benscher family.

Simon Benscher who runs the company with his brother Paul told me they have four hundred corporate clients, and his son Marc fitted all the locks at the Olympics – which is mighty impressive for a business started by their parents Peter & Betty in 1965, selling china, glass and fancy goods from a single shop in the same parade. Originally, Peter & Betty were publicans in Poplar who were sick of getting up at four in the morning and wanted a quieter life.

“Simon joined the business from school but I worked in retail in the West End for fifteen years before I started working for the family,” explained Paul, who spends his days behind the counter while his brother Simon handles the paperwork. “He’s office based, I’m counter based,” admitted Paul, outlining the demarcation of responsibility and acting careworn in an exaggerated fashion when his brother appeared waving an invoice. “We’re just a classic Jewish matriarchal family,” Simon announced, by means of explanation, as Paul telephoned his wife, Sonia, who speaks five languages, for an impromptu translation on behalf of a customer with no English. “I do enjoy serving the public,” Simon assured me, “I’ve served everyone from Princess Anne down.”

The two enterprising brothers took over premises close to their parents’ shop and never looked back. And fifty years after they set up their own shop, Peter & Betty are still involved in the family business.“They turn up twice a week and tell us what we’re doing wrong!” confided Simon affectionately.

Paul Benscher

Simon Benscher

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

You may also like to take a look at

Patricia Niven’s Golden Oldies

At The Charterhouse

Brick buildings of 1531 in Preacher’s Court with the Barbican beyond

Desirous of a second visit to view the magnificence of the Charterhouse more closely, I made another call upon my new friend Brother Hilary Haydon one sunny afternoon last week, using the excuse of undertaking a photoessay, and these pictures – interspersed with lantern slides from the Bishopsgate Institute of the same subject a century ago – are the result.

Hilary is also enamoured by the atmosphere of repose conjured by the ancient buildings and lush gardens at the Charterhouse. “I must say, it is very pleasant to relax here and leave those fellows over in the City doing all that stressful hard work,” he confessed to me, now happily retired and enjoying the peace and quiet, after a long career as a Barrister in the Square Mile.

Carved details of the Gatehouse and the Physician’s House, 1716

Gateway of c1400 with Physician’s House built above in 1716

Cloisters in Preacher’s Court

The Preacher’s House built in the eighteen-twenties

Old pump in Preacher’s Court

Tudor chimneys in Preacher’s Court

The Great Staircase, erected in early seventeenth century and destroyed in 1941

Wash House Court

Passageway into Wash House Court

Master’s Court built in 1546

Great Hall built by Thomas Howard in 1571 while under house arrest here for plotting with Mary Queen of Scots to depose Elizabeth I

Portrait of Thomas Sutton in the Great Hall with Thomas Fenner below

Portrait of Elizabeth Salter attributed to Hogarth in the Great Hall

Chapel Cloister

Chapel Cloister

Tomb of Thomas Sutton, the founder of the Charterhouse

Thomas Sutton

The fifteenth century South Aisle of the Chapel

Brother Hilary Haydon in the North Aisle of the Chapel, added in 1614

Names of Charterhouse schoolboys etched upon the glass in the nineteenth century

Tudor brickwork upon the exterior of Wash House Court

Physician’s House built in 1716

Entrance to the Charterhouse viewed through the former Priory Gate

Knocker upon the main gate

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Tours of the Charterhouse are available by clicking here

You may also like to read about

Viscountess Boudica’s Easter

She may be no Spring chicken but that does not stop the indefatigable Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green from dressing up as an Easter chick!

As is her custom at each of the festivals which mark our passage through the year, she has embraced the spirit of the occasion wholeheartedly – festooning her tiny flat with seasonal decor and contriving a special outfit for herself that suits the tenor of the day. “Easter’s about renewal – birth, life and death – the end of one thing and the beginning of another,” she assured me when I arrived, getting right to the heart of it at once with characteristic forthrightness.

I feel like a child visiting a beloved grandmother or favourite aunt whenever I call round to see Viscountess Boudica because, although I never know what treats lie in store, I am never disappointed. Even as I walk in the door, I know that days of preparation have preceded my visit. Naturally for Easter there were a great many fluffy creatures in evidence, ducks and rabbits recalling her rural childhood. “When my uncle had his farm, I used to put the little chicks in my pocket and carry them round with me,” she confided with a nostalgic grin, as she led me over to admire the wonder of her Easter garden where yellow creatures of varying sizes were gathering upon a small mat of greengrocer’s grass, around a tree hung with glass eggs, as if in expectation of a sacred ritual.

I cast my eyes around at the plethora of Easter cards, testifying to the popularity of the Viscountess, and her Easter bunting and Easter fairy lights that adorned the walls. There could be no question that the festival was anything other than Easter in this place. “As a child, I used to get a twig and spray it with paint and hang eggs from it,” she explained, recalling the modest origin of the current extravaganza and adding, “I hope this will inspire others to decorate their homes.”

“Cadbury’s Dairy Milk is my favourite,” she confessed to me, chuckling in excited anticipation and patting her waistline warily, “I probably will eat a lot of chocolate on Easter Monday – once I start eating chocolate, I can’t stop.” And then, just like that beloved grandmother or favourite aunt, Viscountess Boudica kindly slipped a chocolate egg into my hands as I said my farewell, and I carried it off under my arm back to Spitalfields as a proud trophy of the day.

Viscountess Boudica writes her Easter cards

“yellow creatures of varying sizes were gathering upon a small mat of greengrocer’s grass, around a tree hung with glass eggs, as if in expectation of a sacred ritual”

Viscountess Boudica turns Weather Girl to present the forecast for the Easter Bank Holiday – “I predict a dull start with a few patches of sunshine and some isolated showers. In the West Country, it will be nice all day with temperatures between sixty and eighty degrees Farenheit. There will be a small breeze on the coast and sea temperature of around fifty-nine degrees Farenheit.”

Easter blessings to you from Viscountess Boudica!

Viscountess Boudica and her fluffy friends

Be sure to follow Viscountess Boudica’s blog There’s More To Life Than Heaven & Earth

Take a look at

Viscountess Boudica’s Domestic Appliances

Viscountess Boudica’s Halloween

Viscountess Boudica’s Christmas

Viscountess Boudica’s Valentine’s Day

Viscountess Boudica’s St Patrick’s Day

Read my original profile of Mark Petty, Trendsetter

and take a look at Mark Petty’s Multicoloured Coats

Liam O’Farrell, Artist

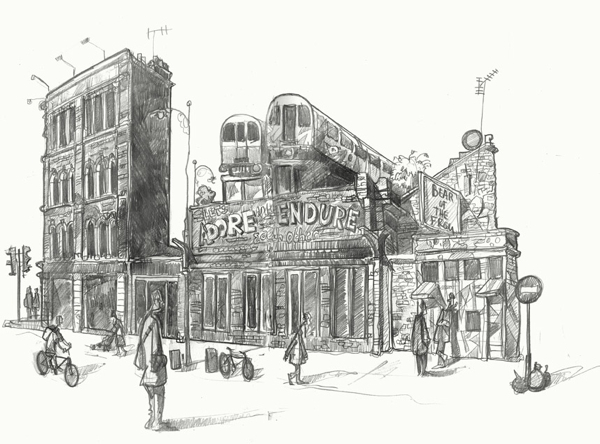

Brick Lane at the corner of Bacon St

Liam O’Farrell delights in painting East End markets in all their shambolic minutiae, often returning to the same subject many times to explore the mutable nature of their architecture and communities.

“I moved to London in 1988 from Portsmouth and at first I spent all my time around the West End, in Leicester Sq and Ed’s Diner in Soho, but after six months it stopped giving anything to me,” he admitted, “My sister worked in the rag trade in the East End and she took me to an old pub and showed me around the streets here, and eventually I moved to Hackney and it felt just like home.”

Living here for more than twenty years brought Liam an intimate knowledge of the streets and kindled his desire to devote himself to drawing and painting fulltime. Yet this realisation also led to his departure. “I realised that if I wanted to do more paintings of London, I needed to not live here anymore, so I reduced my overheads by moving to Somerset in 2011,” he explained. “Now I come back to the East End every couple of weeks and I like to draw in short bursts – especially with the cold and the bloody rain – I make drawings for reference and work them up into paintings in my studio.”

In Liam’s pictures, people and architecture are inextricable and, in spite of their apparent realism, these are images constructed from memory – a synthesis of Liam’s perception of a place and its inhabitants, rather than any literal representation. In his affectionate vision, Liam celebrates the intricate details of the markets and the people that make this place distinctive.

Bacon St

Sclater St Market

Corner of Brick Lane ands Bethnal Green Rd

Columbia Rd

Great Eastern St

Whitechapel Rd

Round Chapel, Hackney

St Andrew Undershaft, St Mary Axe

The Cockpit, City of London

Royal Courts of Justice

St Paul’s Choir School, City of London

St Paul’s Cathedral

Liam O’Farrell at work in Fournier St

Images copyright © Liam O’Farrell