The Spitalfields Weaver

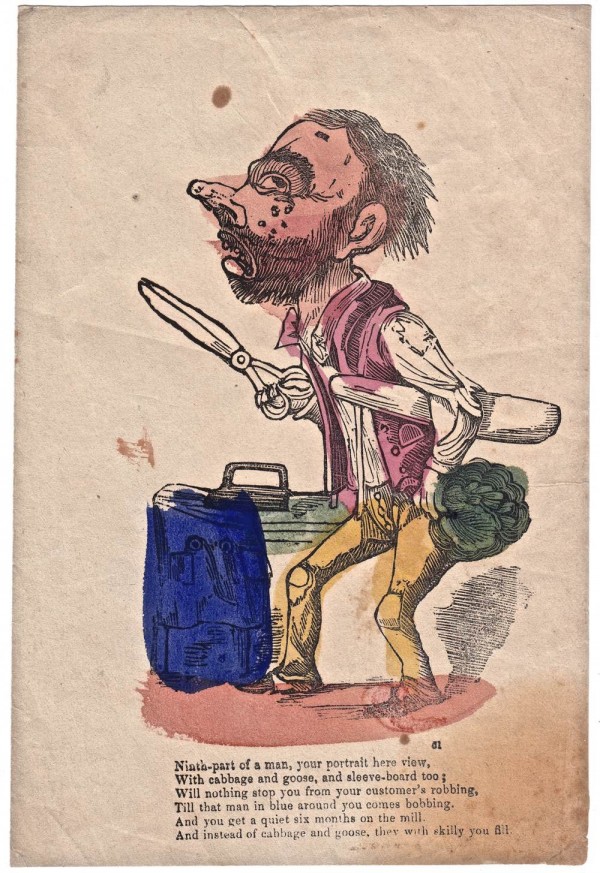

Today I publish these excerpts of Arthur Armitage’s text for Illustrator Kenny Meadows’ The Heads of the People or, Portraits of the English, 1840 concerning The Spitalfields Weaver

Holidays are red letter days for the Spitalfields Weaver. When holiday-making, he attires himself in his best suit which, being characteristic, we shall attempt to describe. His upper garment is a frock coat with a very long waist and prodigious long skirts. Two parallel cords run down either side of his trousers, at the termination of which he displays a pair of highly-polished high-lows, secured across the instep with a strap or a buckle. His throat is confined by a loose bandanna handkerchief tied with studied negligence. His hair is a pale canary tortured into two pensile ringlets of the Corinthian order and surmounted by a glossy silk hat.

The Spitalfields Weaver expresses notions of gallantry at once peculiar and original. For example, he will walk for miles with his ‘betrothed’ on his arm and his hands quietly deposited in his breeches pockets. His favourite suburban resort is Clay Hall, a sort of tea gardens in Old Ford. As might be supposed from his sedentary occupation, the Weaver is more of a meditative than a mercurial temperament. Rural felicity with him is sitting in a close box, exhaling the fumes of tobacco, imbibing copiuos drafts of mild ale and picking shrimps.

The Spitalfields Weaver is by hereditary predilections, a pigeon fancier. Let his family be ever so numerous, his privations ever so great, he must have a pigeon trap on the roof of his domicile, where twice a day, at dinner and tea time, for ten minutes he exhibits the capabilities of his highly-trained covey pouters, tumblers, dragons, Jacobins and carriers. He flaps a long cane and the pigeons fly off and describe concentric circles in the air. Anon, he puts two fingers between his teeth and gives a shrill whistle, when the sagacious creatures immediately return to their lawful habitation.

The Spitalfields Weaver is a passionate lover of harmony. Every Monday night, he attends a concert on the free and easy principle at the ‘Cheshire Cheese.’ His taste in singing, as in everything else, is eccentric. His favourite melodies those which he calls ‘sentimental’ generally relate to shipwrecks and disasters at sea. They never consist of less than fourteen verses of eight lines each and usually occupy from ten minutes to a quarter of an hour in the delivery. He laughs immoderately at comic songs, especially those which touch upon itinerant vendors of greengrocery. Unlike the tailor, who handles with equal dexterity the fiddle and the sleeve board, the Weaver rarely performs upon any instrument. When he does feel musically inclined, he patronises the mouth organ.

If we may credit the assertion of the Weaver, some twenty years ago there was no more flourishing branch of industry in existence than that of the silk weavers of Spitalfields. The introduction of machinery, the multiplication of journeymen, and other causes, have conspired to reduce it to a state with which the situation of a scavenger must be truly eligible. Surprisingly as it may appear, the Weaver while deploring the depressed condition of his trade, as soon as his children are capable, puts them as a matter of course in the loom. The Spitalfields Weaver, whose portrait heads this article, afford a similar example of blind fanaticism. His attachment to weaving being on the grounds of being able to sit all day long.

In the palmy days of weaving, the most-favourite recreation of the Spitalfields Weaver was bull-baiting. A bull, smoking-hot from Smithfield on a Monday afternoon, was looked for by the sporting gentry of Mile End New Town, as regularly as the London mail by the ostlers of a country inn. The streets were lined at an early hour by young gentlemen in their shirt sleeves, each equipped with a knobby club and all on tiptoe of expectation. As soon as the animal appeared in sight, a wild shout of triumph suddenly rent the air, and apprentices – deaf to the call of duty – sprang out of their looms and scampered off to join the melee.

Fairlop Fair has, from the period of its instigation, been annually honoured by the elite of Spitalfields. Early on the first Friday in July, light commodious vans covered with red bordered canvas and tastefully decorated with green boughs, start for Epping Forest, each capable of conveying a double row of ladies and gentlemen, varying in age from one score to three score and in number from twenty-five to thirty-five. Large stone bottles are carefully deposited between the legs of the sterner sex, in order that those who may experience on the road a sudden depression of spirits can be furnished with prompt means of alleviation. A hamper or two secured on the outworks of the conveyance and heavily laden with cold legs of pork affords scope to the imaginations of the silent.

The Spitalfields Weaver when his trade has been particularly stagnant has endeavoured to give it a stimulus by angling for the patronage of royalty. One of the most expensive baits that ever was thrown out to hook a crowned head was a magnificent robe presented by the Weavers of Spitalfields to the fourth George. His majesty, of course, felt highly flattered by this proof of affection in his industrious subjects and pronounced it to be an exquisite piece of workmanship, promised to recommend that the gentlemen of his court abjure India and use pocket handkerchiefs only of home manufacture, and having retired to his dressing room, threw the robe to his valet.

The Spitalfields Weaver next resolved to make a desperate experiment upon the gratitude of female majesty. Accordingly, a bevy of ingenious vestals with spotless hands was elected from the virgin operatives of Spitalfields and dedicated to fabricate a specimen of their ability in reconciling warp and woof for the adornment of their beloved sovereign. The work was finished and taken with all due ceremony to the palace. Her majesty at once candidly confessed that she had never seen anything one half so beautiful. The ladies of her court (like gentlemen of the former) were one and all instructed, on the spot, to provide themselves with articles of apparel from a similar source with all convenient expedition.

To facilitate the execution of this benevolent design, a proclamation was issued commanding all the housemaids in the royal establishment to cast aside any dress of silken fabric they might have in their use or possession, and assume forthwith the more-becoming garb of merinos, stuffs and printed cottons. The Weaver’s bosom was filled with joy and the housekeeper’s room with indignation.

The poor Weaver saw in his sleep a vision of St James glittering in the effulgence of Spitalfields silks, while the persecuted housemaids saw nothing but degradation. At length, the royal household began to talk of the imperative necessity for republican institutions and, meanwhile, the Spitalfields operatives discoursed calmly on the serene beauty of the monarchy. Time flew on, the housemaids knew not what course to pursue and the weaver pointed to himself and and bade them learn a beneficial lesson of resignation.

Spitalfields Weaver

Illustrator Kenny Meadows and his Portraits of the English

You may also like to take a look at

The Principal Operations of Weaving, 1748

Start Your Own Blog In 2016

Today, I published blogs by two alumni of the Spitalfields blog course, A London Inheritance and Bug Woman London. If you are contemplating starting your own blog in 2016, there is still time to sign up for the course on 30th & 31st January. Scroll down for further information.

A LONDON INHERITANCE

My father was born in London in 1928, lived in the city throughout World War II and took photographs of the capital from 1946 to 1954. These show a city which has changed dramatically and, through A London Inheritance, I document my exploration of London, using his photographs as a starting point, trying to identify the original locations and show how the buildings, streets and topography of the capital have developed.

I walked down to the Tower one Sunday to see how much had changed. The majority of the cannon have been removed, although a couple remain, looking rather sad up against the approach to Tower Bridge at the far end of the photo. I do not know when they were removed or why, I can only guess. Perhaps Health & Safety considerations? Although falling was an accepted risk of climbing anything as a boy. An understandable reason could have been damage to the cannon. Making more space in this area is possible, as it really does get crowded at the peak of the tourist season. Or perhaps the fact that they all seemed to be pointing directly at City Hall on the south bank of the river may have made certain occupants rather nervous?

Whilst the majority of my father’s photos came to me as negatives, a number were printed, and of these some had the location written on the back. On this photo, my father had written the simple title “Autumn in Finsbury Circus.” Taken early in the morning, it shows autumnal light shining through the trees with the first fallen leaves on the path. I suspect that he had taken this photo for a competition at the St. Brides Institute Photographic Society as it has a more composed quality than the straight-forward recording of buildings and streets. To try and find the location of this photo, a day off from work provided the opportunity for a walk around London. Finsbury Circus is much the same today, with one significant exception being that it is a site for Crossrail, however parts that remain open show that not too much has changed (if you ignore the major construction to your left).

My father’s photo of the Lamb & Flag in Rose St, Covent Garden, was taken in 1948. Barclay, Perkins & Co. Ltd operated from the Anchor Brewery in Park St, Southwark, originally founded in 1616, and becoming Barclay, Perkins in 1781 when John Perkins & Robert Barclay took over. Barclay, Perkins & Co merged with Courage in 1955 and the brewery closed in the early seventies.

The Lamb & Flag occupies one of London’s older buildings. It was originally built at the same time as Rose Street in 1623 and much of the original timber frame survives, although the front was rebuilt in 1958 as can be seen in my photo. The rebuild lost many of the original architectural features including what appears to be a parapet running the width of the building with a carving of the Lamb and Flag at the centre. The ‘lamb’ is from St John, “Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sins of the world” while the flag is that of St George. The pub was also once known as the ‘Bucket of Blood’ due to links with prize fighting.

BUG WOMAN LONDON

Bug Woman is a slightly scruffy middle-aged woman who enjoys nothing more than finding a large spider in the bathroom. She plans to spend the next five years exploring the parks, woods and pavements within a half-mile radius of her North London home, and reporting on the animals, plants and people that she finds there. She will also be paying close attention to the creatures that turn up in the garden and the house. She promises to post every week on a Saturday, and more often if she can tear herself away from the marmalade making. She looks forward to finding out what’s happening in your half-mile.

Although I usually write about the wildlife outside my house, today I would like to share some tales with you about the creatures that we actually select as our companions. My husband and I began to foster cats for the Cats Protection League back in 2008, because for me a house without a pet is not a home.

During our five years of fostering, we looked after nearly eighty cats and learned a lot about non-attachment, about how every cat is different, and how tolerant it was possible to be in the face of feline bodily fluids. We also developed a clear idea of the kind of cat that we would want to adopt. So here, in no particular order, are some of the cats that were in our care, sometimes for weeks, sometimes for months.

We looked after Rosie when her owners went away on holiday. She was a cat with quite severe disabilities – she could not stand up, and had to be helped to her litter tray a couple of times a day. She would always let you know when she wanted to go, which was generally at the human-friendly times of 8:00am and 6:00pm. She was a very perky cat, interested in everything that was going on, and loved to sit on the sofa next to you or to be picked up for a cuddle. She also loved other cats, but they generally knew that there was something wrong with her and would avoid her. Until, that is, her owner adopted another little cat who had been through the most horrific abuse I had ever heard of. He loved Rosie on sight, and would cuddle up with her in her basket – maybe she reminded him of his mother, or maybe he just recognised another cat that wasnot able to deal with the world around her on her own. At any rate, the two of them were a comfort to one another throughout their lives.

Rosa was the only cat who gave birth to her kittens in our house. And what an event it was! We had prepared several places for the big event, but of course she had her babies squeezed between the bookshelf and the radiator, on the 4th November. On the 5th November there was a Guy Fawkes party in the street, with deafening explosions and shouting and general carry-on, but she stayed firm despite it all. When the kittens first came out from their hiding place after a few weeks, she spent a lot of time trying to corral them by tapping them with her front feet, like a footballer trying to dribble the ball, but eventually she gave up and let them start to explore. We felt like proud parents!

Tabby was a lynx in miniature. Look at the size of those paws! He grew to be enormous, and was the gentlest kitten we ever looked after, happy to lie in your arms like a baby.

Colette was rescued from a house fire – in fact, the cat carrier in which she was saved was melted like a Salvador Dali painting. She smelled of smoke for days and also had a brutal flea infection. She made a quick recovery – however – and was soon off to her new home, where – hopefully – they had made sure the wiring was not a death-trap.

Galaxy came to us with a terrible throat lesions, an allergic reaction to his vaccinations and a general air of depression. Mother cats who are not vaccinated can pass calicivirus onto their kittens, which leaves them with a lifelong tendency to throat and mouth inflammation. Galaxy’s throat was so painful that there was some talk of putting him to sleep if the situation did not improve, and so we spoilt him horribly. We let him slept on our bed, in spite of his snoring. He got all the best food. We put up with his outrageous flatulence. And, lo and behold, he gradually improved, and was finally (after a year) re-homed with a wonderful lady who gave him venison and wild boar at Christmas, and did not mind him sleeping in her potted plants on the patio. He lived for another five years, and was so cherished that he was frequently featured on his owner’s Christmas cards.

Honey was a most unfortunate-looking cat. She was as round as a beach ball and had a most disapproving expression (not helped by her moustache). However, she was an affectionate cat, and would sit beside you, purring like an idling engine. If you did not stroke her, she would reach out with one paw and place it on your arm until you produced the desired caresses. If they stopped, she would pause for a moment and then apologetically reach out again. Eventually, she found a home with someone who could see past her unfortunate looks to the characterful creature beneath.

Mocha & Latte were described to us by the people at the cat shelter as ‘the Cappuccino Kits’ but they arrived as two lively adolescent lunks, with all the social graces of a troop of teddy boys. One afternoon, Latte decided to run up our full-length sitting room curtains, and, before I could stop him, Mocha tried to do the same. Unfortunately, Mocha was twice the weight of Latte and so the entire curtain rail, complete with an enormous chunk of plaster, came out of the wall, leaving a cloud of dust. Suffice to say that they were both in hiding for at least five minutes before they ventured out to inspect the damage.

Talking of adolescent lunks, Lee was our first teenager, and were a whole heap of trouble. Lee was forever jumping out of open windows, hiding on the top of bookcases and, on one occasion, getting into the washing machine.

So what do you think happened when we finally decided to adopt? Was it a big tough tomcat, full of personality and affection? Umm, no.

Our last two foster cats were a brother and sister: a big tough tom, and an extremely shy little female cat. The big tough tom was adopted out to Gerrard’s Cross, to a man who owned a stable full of show jumpers and who did not mind if his cat wanted to sleep on the bed. This just left the female, who, up to then, had spent her whole time hiding behind the sofa.

John and I wondered who, on earth, would ever adopt a cat who never showed herself. The months went on. Nobody wanted a very ordinary little black and white scaredy cat. And yet, we had started to notice that she was not such a scaredy cat any more. She liked to be brushed, for just a minute or so at first. Eventually, she would demand to be brushed, and complain when you stopped.

We stopped thinking about her in terms of “Who else will adopt this cat if we don’t?” and started to realise that, for us, she was ideal. She did not hunt and kill the creatures in my garden. She respected our sleep time. She did not have any strange problems with food. She did rip the sofa to shreds. So, Gentle Reader, we adopted her, and put away all notions of the cats that we thought we wanted, in favour of the one that we actually did.

Every animal has a personality. If we can understand this with our pets, I wonder why we find it so hard to acknowledge that wild animals might be the same?

COMMENTS BY STUDENTS FROM PREVIOUS SPITALFIELDS BLOG COURSES

“I highly recommend this creative, challenging and most inspiring course. The Gentle Author gave me the confidence to find my voice and just go for it!”

“Do join The Gentle Author on this Blogging Course in Spitalfields. It’s as much about learning/ appreciating Storytelling as Blogging. About developing how to write or talk to your readers in your own unique way. It’s also an opportunity to “test” your ideas in an encouraging and inspirational environment. Go and enjoy – I’d happily do it all again!”

“The Gentle Author’s writing course strikes the right balance between addressing the creative act of blogging and the practical tips needed to turn a concept into reality. During the course the participants are encouraged to share and develop their ideas in a safe yet stimulating environment. A great course for those who need that final (gentle) push!”

“I haven’t enjoyed a weekend so much for a long time. The disparate participants with different experiences and aspirations rapidly became a coherent group under The Gentle Author’s direction in a gorgeous house in Spitalfields. There was lots of encouragement, constructive criticism, laughter and very good lunches. With not a computer in sight, I found it really enjoyable to draft pieces of written work using pen and paper. Having gone with a very vague idea about what I might do I came away with a clear plan which I think will be achievable and worthwhile.”

“The Gentle Author is a master blogger and, happily for us, prepared to pass on skills. His “How to write a blog” course goes well beyond offering information about how to start blogging – it helps you to see the world in a different light, and inspires you to blog about it. You won’t find a better way to spend your time or money if you’re considering starting a blog.”

“I gladly traveled from the States to Spitalfields for the How to Write a Blog Course. The unique setting and quality of the Gentle Author’s own writing persuaded me and I was not disappointed. The weekend provided ample inspiration, like-minded fellowship, and practical steps to immediately launch a blog that one could be proud of. I’m so thankful to have attended.”

“I took part in The Gentle Author’s blogging course for a variety of reasons: I’ve followed Spitalfields Life for a long time now, and find it one of the most engaging blogs that I know; I also wanted to develop my own personal blog in a way that people will actually read, and that genuinely represents my own voice. The course was wonderful. Challenging, certainly, but I came away with new confidence that I can write in an engaging way, and to a self-imposed schedule. The setting in Fournier St was both lovely and sympathetic to the purpose of the course. A further unexpected pleasure was the variety of other bloggers who attended: each one had a very personal take on where they wanted their blogs to go, and brought with them an amazing range and depth of personal experience. “

“I found this bloggers course was a true revelation as it helped me find my own voice and gave me the courage to express my thoughts without restriction. As a result I launched my professional blog and improved my photography blog. I would highly recommend it.”

“An excellent and enjoyable weekend: informative, encouraging and challenging. The Gentle Author was generous throughout in sharing knowledge, ideas and experience and sensitively ensured we each felt equipped to start out. Thanks again for the weekend. I keep quoting you to myself.”

“My immediate impression was that I wasn’t going to feel intimidated – always a good sign on these occasions. The Gentle Author worked hard to help us to find our true voice, and the contributions from other students were useful too. Importantly, it didn’t feel like a ‘workshop’ and I left looking forward to writing my blog.”

“The Spitafields writing course was a wonderful experience all round. A truly creative teacher as informed and interesting as the blogs would suggest. An added bonus was the eclectic mix of eager students from all walks of life willing to share their passion and life stories. Bloomin’ marvellous grub too boot.”

“An entertaining and creative approach that reduces fears and expands thought”

“The weekend I spent taking your course in Spitalfields was a springboard one for me. I had identified writing a blog as something I could probably do – but actually doing it was something different! Your teaching methods were fascinating, and I learnt a lot about myself as well as gaining very constructive advice on how to write a blog. I lucked into a group of extremely interesting people in our workshop, and to be cocooned in the beautiful old Spitalfields house for a whole weekend, and plied with delicious food at lunchtime made for a weekend as enjoyable as it was satisfying. Your course made the difference between thinking about writing a blog, and actually writing it.”

“After blogging for three years, I attended The Gentle Author’s Blogging Course. What changed was my focus on specific topics, more pictures, more frequency, more fun. In the summer I wrote more than forty blogs, almost daily from my Tuscan villa on village life and I had brilliant feedback from my readers. And it was a fantastic weekend with a bunch of great people and yummy food.”

“An inspirational weekend, digging deep with lots of laughter and emotion, alongside practical insights and learning from across the group – and of course overall a delightfully gentle weekend.”

“The course was great fun and very informative, digging into the nuts and bolts of writing a blog. There was an encouraging and nurturing atmosphere that made me think that I too could learn to write a blog that people might want to read. – There’s a blurb, but of course what I really want to say is that my blog changed my life, without sounding like an idiot. The people that I met in the course were all interesting people, including yourself. So thanks for everything.”

“This is a very person-centred course. By the end of the weekend, everyone had developed their own ideas through a mix of exercises, conversation and one-to-one feedback. The beautiful Hugenot house and high-calibre food contributed to what was an inspiring and memorable weekend.”

“It was very intimate writing course that was based on the skills of writing. The Gentle Author was a superb teacher.”

“It was a surprising course that challenged and provoked the group in a beautiful supportive intimate way and I am so thankful for coming on it.”

“I did not enrol on the course because I had a blog in mind, but because I had bought TGA’s book, “Spitalfields Life”, very much admired the writing style and wanted to find out more and improve my own writing style. By the end of the course, I had a blog in mind, which was an unexpected bonus.”

“This course was what inspired me to dare to blog. Two years on, and blogging has changed the way I look at London.”

HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ – 30th & 31st JANUARY

Spend a weekend in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Spitalfields and learn how to write a blog with The Gentle Author.

This course will examine the essential questions which need to be addressed if you wish to write a blog that people will want to read.

“Like those writers in fourteenth century Florence who discovered the sonnet but did not quite know what to do with it, we are presented with the new literary medium of the blog – which has quickly become omnipresent, with many millions writing online. For my own part, I respect this nascent literary form by seeking to explore its own unique qualities and potential.” – The Gentle Author

COURSE STRUCTURE

1. How to find a voice – When you write, who are you writing to and what is your relationship with the reader?

2. How to find a subject – Why is it necessary to write and what do you have to tell?

3. How to find the form – What is the ideal manifestation of your material and how can a good structure give you momentum?

4. The relationship of pictures and words – Which comes first, the pictures or the words? Creating a dynamic relationship between your text and images.

5. How to write a pen portrait – Drawing on The Gentle Author’s experience, different strategies in transforming a conversation into an effective written evocation of a personality.

6. What a blog can do – A consideration of how telling stories on the internet can affect the temporal world.

SALIENT DETAILS

The course will be held at 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields on 30th & 31st January from 10am -5pm on Saturday and 11am-5pm on Sunday. Lunch will be catered by Leila’s Cafe of Arnold Circus and tea, coffee & cakes by the Townhouse are included within the course fee of £300.

Accomodation at 5 Fournier St is available upon enquiry to Fiona Atkins fiona@townhousewindow.com

Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book a place on the course.

One Day Young

For more than five years, Jenny Lewis has been photographing mothers and their babies within twenty four hours of birth in Hackney and more recently she has supplemented these with a series of portraits from Malawi. I can think of no better way to begin the New Year than this contemplation of the joy, resilience and intimacy of motherhood.

Nicky & Oscar

Ana & Barney

Joyce & baby

Karin & Johannes

Gitta & Til

Esther & Joyce

Lorien & Tam

Hazel & Rudy

Jennifer & Jonathan

Sarah & baby

Helen & Hudson

Jenny & Suki

Elfrida & son

Meredith & Lina

Joti & Kiran

Justina & Joseph

Rebecca & Osiris

Tara & Inca

Madalitso & Linda

Jhanne & Lily

Nicola & Jemima

Miriam & Caroline

Martha & baby

Olivera & Albie

Salome & baby

Karla & River

Laura & Finn

Esnart & baby

Theresa & Tommy

Rosie & Buddy

Margaret & baby

Tamysen & Eve

Trinidad & Carmen

Suprawadee & Eveline

Katy & Ada

Lizzie & Fred

Alinafe & Boyson

Tessa & Lois

Kyle & Winona

Judith & Adamisi

Dilek & Noah

Clemmie & Imo

Rita & Ruth

Photographs copyright © Jenny Lewis

Click here to buy a copy of Jenny Lewis’ book ‘One Day Young’ from Hoxton Mini Press

You may also like to take a look at

So Long, Pam Chawla (Mama Thai)

On the last day of the year, I remember Pam Chawla of Mama Thai who died in November. In recent years, Mama Thai had been a favourite destination for lunch where I was always greeted like one of the family by Pam & her husband Raj – and when the winter got cold, Pam fed me with spicy curry and Raj gave me special tea that never failed to alleviate any cold or flu. Mama Thai was a much-loved Spitalfields institution and Pam will be keenly missed.

Pam & Raj Chawla, proprietors of ‘Mama Thai,’ began selling noodles from a wooden hut in the Spitalfields Market on the very first day it reopened after the wholesale Fruit & Vegetable Market moved out in 1991. I used to go every Sunday and perch on a bench in the cavernous empty market to wolf a steaming plate of Mama Thai’s spicy noodles with chilli sauce. Before the renovations, there was a train that gave rides around the Market, there were football pitches and all kinds of community events, of which the dog show was most notable, and, sitting amongst all this chaotic life, Thai noodles were the perfect dish to warm my body and raise spirits after trudging around Columbia Rd and Brick Lane in the frost.

When the Market was renovated, Pam & Raj opened a shop at the corner of Toynbee St and Brune St, fifty yards down a side street from Christ Church, where hordes of office workers came every day to carry off dishes of their delicious and keenly-priced noodles and curry for lunch. A cooked meal for under five pounds is rare now – especially in Spitalfields – yet at Mama Thai you could buy good quality food prepared daily from fresh ingredients and get change from five pounds. There was a touching egalitarianism about this welcoming, brightly coloured restaurant, run with pride by Pam & Raj for a loyal coterie of regular customers, who kept coming back to show their appreciation.

Yet, although in the last quarter century, Mama Thai only moved a hundred yards from the Spitalfields Market to Toynbee St, the story began far away on another continent and it is a saga that involves both hard work and romance in equal measure.

Raj Chawla, our hero, was a restless spirit with perceptive dark eyes, who won a scholarship from India to study in Germany and, upon his return in 1971, decided to seek a life in Thailand. He learnt to cook in an American grill and managed a German restaurant in Bangkok, living above the shop. It was there that the demure Pam, our heroine, caught his attention when she came to sit in the restaurant, engendering a tender romance which continued for the rest of their lives. Together, the couple came to London in 1975 on a work permit to study hotel management, starting a stall at Camden Lock each weekend selling noodles cooked by Pam, who like many great cooks was self-taught, improvising her dishes and learning through experience.

On the first day trading in Spitalfields, Mama Thai took just twenty pounds but, over time, business grew to capacity. Then, in spite of Pam & Raj’s perseverance, Mama Thai had to leave the market when renovations replaced the wooden huts with steel and glass spaces now occupied by chain restaurants and commanding a rent beyond the turnover of a small independent. It took Pam & Raj a year to find their new premises, but it is a credit to their tenacity that while homogenous restaurants closed in their expensive central locations, Mama Thai deservedly thrived in this side street where discerning thrifty diners sought them out.

Five years ago, Raj took retirement after nineteen years at his job at the post office and Pam taught him to cook vegetarian dishes. “She’s the boss,” confirmed Raj, indicating Pam who glided around concealing her deep concentration with effortless poise and an easy smile. Possessing the immaculate hair, make-up and inscrutable grace of a forties’ screen goddess and ruling the kitchen with unspoken authority, Pam was capable of speaking volumes simply by raising a single eyebrow, which was exactly what she did at that moment, endorsing Raj’s statement.

I was putting away my notebook before lunch when a passing office worker, shovelling noodles into his mouth with clownish delight as he walked out the door, announced spontaneously to the world, “This is where I come when I’m hungry!” Pam & Raj laughed, because he proved their point – out of hard work and talent, they created a beautiful restaurant offering good food that everyone could afford and we all loved them for it.

The celebrated Pam Chawla, Mama Thai herself, stands holding Raj’s arm (standing second from left) when a new sign by Robson Cezar (front right) was installed last year

Pam & Raj portrait copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Group portrait copyright © Sarah Ainslie

A Night At The Beigel Bakery

New Year’s Eve is always the busiest night of the year at the Brick Lane Beigel Bakery, so a few years ago I chose to spend the night of 30th December accompanying Sammy Minzly, the celebrated manager of this peerless East End institution, to observe the activity through the early hours as the staff braced themselves for the rush. Yet even though it was a quiet night – relatively speaking – there was already helter-skelter in the kitchen when I arrived mid-evening to discover five bakers working at furious pace amongst clouds of steam to produce three thousand beigels, as they do every day of the year between six at night and one in the morning.

At the centre of this tiny bakery which occupies a lean-to at the rear of the shop, beigels boiled in a vat of hot water. From here, the glistening babies were scooped up in a mesh basket, doused mercilessly with cold water, then arranged neatly onto narrow wet planks named ‘shebas,’ and inserted into the ovens by Stephen the skinny garrulous baker who has spent his entire life on Brick Lane, working here in the kitchen since the age of fifteen. Between the ovens sat an ogre of a huge dough-making machine, mixing all the ingredients for the beigels, bread and cakes that are sold here. It was a cold night in Spitalfields, but it was sweltering here in the steamy atmosphere of the kitchen where the speedy bakers exerted themselves to the limit, as they hauled great armfuls of dough out of the big metal basin in a hurry, plonking it down, kneading it vigorously, then chopping it up quickly, and using scales to divide it into lumps sufficient to make twenty beigels – before another machine separated them into beigel-sized spongey balls of dough, ripe for transformation.

In the thick of this frenzied whirl of sweaty masculine endeavour – accompanied by the blare of the football on the radio, and raucous horseplay in different languages – stood Mr Sammy, a white-haired gentleman of diminutive stature, quietly taking the balls of dough and feeding them into the machine which delivers recognisable beigels on a conveyor belt at the other end, ready for immersion in hot water. In spite of the steamy hullabaloo in the kitchen, Mr Sammy carries an aura of calm, working at his own pace and, even at seventy-five years old, still pursues his ceaseless labours all through the night, long after the bakers have departed to their beds. Originally a baker, he has been working here since the beigel bakery opened at these premises in 1976, although he told me proudly that the Brick Lane Beigel Bakery superceded that of Lieberman’s fifty -five years ago. Today it is celebrated as the most visible legacy of the Jewish culture that once defined Spitalfields.

Hovering at the entrance to the kitchen, I had only to turn my head to witness the counterpoint drama of the beigel shop where hordes of hungry East Londoners line up all night, craving spiritual consolation in the form of beigels and hot salt beef. They come in sporadic waves, clubbers and party animals, insomniacs and sleep walkers, hipsters and losers, street people and homeless, cab drivers and firemen, police and dodgy dealers, working girls and binmen. Some can barely stand because they are so drunk, others can barely keep their eyes open because they are so tired, some can barely control their joy and others can barely conceal their misery. At times, it was like the madhouse and other times it was like the morgue. Irrespective, everyone at the beigel bakery keeps working, keeping the beigels coming, slicing them, filling them, counting them and sorting them. And the presiding spirit is Mr Sammy. Standing behind the counter, he checks every beigel personally to maintain quality control and tosses aside any that are too small or too toasted, in unhesitating disdain.

As manager, Mr Sammy is the only one whose work crosses both territories, moving back and forth all night between the kitchen and the shop, where he enjoys affectionate widespread regard from his customers. Every other person calls out “Sammy!” or “Mr Sammy” as they come through the door, if he is in the shop – asking “Where’s Sammy?” if he is not, and wanting their beigels reheated in the oven as a premise to step into the kitchen and enjoy a quiet word with him there. Only once did I find Mr Sammy resting, sitting peacefully on the salt bin in the empty kitchen in the middle of the night, long after all the bakers had left and the shop had emptied out. “I’m getting lazy! I’m not doing nothing.” he exclaimed in alarmed self-recognition, “I’d better do something, I’d better count some beigels.”

Later he boiled one hundred and fifty eggs and peeled them, as he explained me to about Achmed, the cleaner, known as ‘donkey’ – “because he can sleep anywhere” – whose arrival was imminent. “He sleeps upstairs,” revealed Mr Sammy pointing at the ceiling. “He lives upstairs?” I enquired, looking up. “No, he only sleeps there, but he doesn’t like to pay rent, so he works as a cleaner.” explained Mr Sammy with an indulgent grin. Shortly, when a doddery fellow arrived with frowsy eyes and sat eating a hot slice of cake from the oven, I surmised this was the gentlemen in question. “I peeled the eggs for you,” Mr Sammy informed him encouragingly, a gesture that was reciprocated by ‘donkey’ with the merest nod. “He’s seventy-two,” Mr Sammy informed me later in a sympathetic whisper.

Witnessing the homeless man who came to collect a pound coin from Mr Sammy nightly and another of limited faculties who merely sought the reassurance of a regular handshake, I understood that because it is always open, the Beigel Bakery exists as a touchstone for many people who have little else in life, and who come to acknowledge Mr Sammy as the one constant presence. With gentle charisma and understated gesture, Mr Sammy fulfils the role of spiritual leader and keeps the bakery running smoothly too. After a busy Christmas week, he was getting low on bags for beigels and was concerned he had missed his weekly deliver from Paul Gardner because of the holiday. The morning was drawing near and I knew that Paul was opening that day for the first time after the break, so I elected to walk round to Gardners Market Sundriesmen in Commercial St and, sure enough, on the dot of six-thirty Paul arrived full of good humour to discover me and other customers waiting. Once he had dispatched the customers, Paul locked the shop again and we drove round to deliver the twenty-five to thirty thousand brown paper bags that comprise the beigel shop’s weekly order.

Mr Sammy’s eyes lit up to see Paul Gardner carrying the packets of bags through the door in preparation for New Year’s Eve and then, in celebration of the festive season, before I made my farewells and retired to my bed, I took advantage of the opportunity to photograph these two friends and long-term associates together – both representatives of traditional businesses that between them carry significant aspects of the history and identity of Spitalfields.

Old friends, Paul Gardner, Market Sundriesman, and Sammy Minzly, Manager of the Beigel Bakery.

On The East End Milk Round At Christmas

Monday was the first delivery after Christmas for Kevin Read, the heroic milkman who delivers the milk to Spitalfields and a whole expanse of the East End stretching from the Olympic Park in the East to Hoxton Square in the West. After a heavy downpour, on such a damp occluded morning, while the rest of the world were still dozing in their warm beds, it was my pleasure to join Kevin on his round to offer some companionship in his lonely vigil.

“I worked Christmas Days in this job back in the nineteen eighties,” Kevin recalled without sentiment, cheerful that those times are behind him as we sped along in the heated cabin of his diesel-powered float.“When I had the electric float with the open cabin, I used to be white down one side of my body by the time I arrived at my first call on snowy mornings,” he added with a shudder.

As we drove up through Hackney from Spitalfields in the darkness of the early morning, I spotted a few souls shivering at bus stops, cleaners and service workers reluctantly off to work, and we passed several beaten-up vans of totters cruising the streets to salvage abandoned washing machines and other scrap metal discarded over Christmas. The road sweepers were out too, muffled up in hooded windcheaters like fluorescent Eskimos, dutifully cleaning up the gutters in the night.

“With so many people away, it’s difficult to keep track,” said Kevin, rolling his eyes crazily as he scrabbled through his round book, “I should save time, but I have to keeping checking the books – so I don’t, I just lose money.” With an income consisting entirely of commission on sales, Kevin is used to seeing his earnings plummet at this time of year when offices are shut and customers go away, reducing his weekly delivery from eight thousand to two thousand pints.“After buying diesel for the van, I’ll be lucky if I see twenty pounds for today’s work.” he admitted to me with a shrug, squinting through the windscreen into the murky depths beyond. Yet in recognition of his popularity in the East End, Kevin takes consolation that his Christmas tips were up this year. “People are getting to know me, I’m becoming part of the family!” he reassured me with a cocky smirk, before he ran off into the dark with a wind-up torch and a handful of milk bottles.

“How are you supposed to read a damp note in the dark?” he asked, as he returned from the rain, playfully waving a soggy piece of paper between two fingers, “It’s like being down a coal mine with your eyes shut out there.” The note read “No Milk till Tuesday,” but today was Tuesday. Kevin and I looked at each other. Did the note mean this Tuesday or next Tuesday ? “You need to be mind reader in this job!” observed Kevin, with a wry grimace – though, ever conscientious, he elected to leave milk and make a detour to discover the outcome next day.

For four hours we drove around that cold morning, as the sky lightened and the streetlights flickered out, to deliver two hundred pints of milk, twisting and turning through the streets and housing estates, in what appeared to be an unpopulated city. And Kevin seemed to loosen up, overcoming his stiffness, and constantly checking the pen which was the marker in his round book, dividing the calls done from those still to do, as he made sharp work of his scattered deliveries. In some streets, Kevin makes one call and in others a cluster. It is both inexplicable and a matter of passionate fascination to Kevin – trying to discover the pattern in this chaos. Because if he can unlock the mystery, perhaps he might restore the lost milk rounds of the East End and go from one door to the next delivering milk again, as he did when he began over thirty years ago.

At the end of his short Christmas round, Kevin could go home and have a nap, but he seemed dis-satisfied. “I sometimes think I’d like just this round, without the extra pressure of the office deliveries.” he brooded, envisaging this hypothetical future before dismissing it, smiling in recognition of his own nature, “I’d work three until seven, be done and dusted, and home by eight in the morning – but I’d be so bored.”

The truth is that Kevin provides a public service as much as he is in business, and while it may not make him rich, he shows true nobility of spirit in his endeavour. Renowned for his humour and resilience, it is a matter of honour for Kevin to go out and deliver the milk, working alone unseen in the night for all these years to uphold his promise to his customers, whatever the weather. He takes the rigours of the situation as a test, moulding his character, and this is how he has emerged as an heroic milkman, with stamina and dreams.

There is a myth that it is cheaper to buy milk in a supermarket or shop than have it delivered, but this is false. So why not consider having Kevin deliver to you in the New Year ? – because it is a beautiful thing to discover milk in glass bottles on your doorstep in the morning.

If you want Kevin Read to deliver milk or yoghurt or eggs or fresh bread or even dogfood to you, contact him directly by calling 07940095775 or email kevinthemilkman@yahoo.co.uk. Kevin says, “You don’t have to have a delivery every day,” and “No order is too small.”

You may also enjoy

So Long, Mike Henbrey

Last summer, I was asked if I would meet Mike Henbrey, Collector of Books, Ephemera & Tools, to create a portrait of him in the last few weeks of his life. In the event, we struck up a brief friendship in which I visited Mike over successive Saturdays for more than a month and he survived until November. Now, as the year draws to a close, I remember Mike and his beloved collections.

Mike Henbrey

On the outside, Mike Henbrey’s council flat looked like any other – but once you stepped inside and glimpsed the shelves of fine eighteenth century leather bindings, you realised you were in the home of an extraordinarily knowledgeable collector. High up in the building, Mike sat peacefully in his nest of books, brooding and gazing out at the surrounding tree tops through his large round steel glasses and looking for all the world like a wise old owl.

Walls lined with diverse pairs of steel dividers and shelves of fat albums testified to his collections of tools and ephemera. It was all the outcome of a trained eye and a lifetime of curiosity, seeking out wonders in the barrows, markets and salerooms of London, enabling Mike to amass a collection far greater than his means through persistence and knowledge.

“Of all my collections, the Vinegar Valentines are the one that gives me the most pleasure,” he assured me with characteristic singularity, despite his obviously kind nature. ‘Vinegar Valentines’ were grotesque insults couched in humorous style, sent to enemies and unwanted suitors, and to bad tradesmen by workmates and dissatisfied customers. Unsurprisingly, very few have survived which makes them incredibly rare and renders Mike’s collection all the more astonishing. Immensely knowledgeable yet almost entirely self-educated, Mike was drawn to neglected things that no-one else cared for and this was the genius of his collecting instinct.

Of course, I wanted to pore through all of Mike’s books and albums, but I had to resist this impulse in order to discover his own story and learn how it was that he came to gather his wonderful collection.

“I was born in Chingford in 1943 but, unfortunately, we moved to Norfolk when I was eight. I never liked it there, it was a lonely, cold and draughty place. My father James was a furrier and his father – who was also James – had been a furrier before him in the East End, but they moved out. My mother, Laura Lewis, was a machinist who worked for my father and I think she came from the East End too. I grew up playing in the furriers because my father had his factory in the back garden and the machinists gave me sweets. I think that’s where I got my love of tools.

There was quite a lot of bombing in Chingford during the war and the house next to us got a direct hit which left a great big crack in our wall. I played on bomb sites even though I was told not to, and somehow my mother always seemed to know. I think it must have been the mixture of brick dust and soot on my clothes.

It was a filthy dirty job, being a furrier, and, although my father was a good furrier, he wasn’t a good businessman and he ended up in bankruptcy when I was eight. So that’s how we ended up in Mundesley by the sea in North Norfolk in the early fifties.

As soon as I left school at sixteen, I headed back to London. Ostensibly, it was to complete my training in the catering trade but I hated it, I had already done a year at catering college in Norwich. In reality, I was taking lots of drugs – dope and speed mostly – and working at a night club. I got a job on the door of club called The Bedsitter in Holland Park Avenue. I actually had a bedsitter off Holland Park itself for five pounds a week with a gas ring in the corner. That was a good time.

I worked at a hotel in Park Lane for a few months. The chef used to throw things at me. They fired me in the end for turning up late. I drifted through life by signing on and working on the side, and the club gave me a good social life. I’m a vicarious hedonist. I’ve always read a lot, I taught myself to read by reading my brother’s copies of Dandy and Beano. He was ten years older than me and he died in his early thirties.

A hippy friend of mine was a packer at a West End bookshop in Grafton St and he got me a job there. I worked for Mr Sawyer, he was a nice man. He employed hippies because they didn’t mind his cigar smoke and he never noticed the smell of pot in the packing room. He employed me as a porter but he told me to buy a suit and I got a job in the bookshop itself. I learnt such a lot while I was there. It was nice to be around books, so much better than working for a living.

Mr Gibbs was the shop manager, he taught me how to catalogue. He couldn’t understand why he kept finding more money in his pay packet. It was because we youngsters kept asking for a pay rise and Mr Sawyer couldn’t give it to us without giving it to Mr Gibbs too.

Mr Gibbs taught me not to speak to Mr Sawyer until he’d been around to Brown’s Hotel for his ‘breakfast’ and I presume this was because ‘breakfast’ consisted of at least three gin and tonics. He was a kind employer, he didn’t pay much but you learnt a lot. He had a tiny desk hidden behind a bookcase with two old spindly chairs that were permanently on the brink of collapse. The place was a university of sorts. I learnt so much so quickly. You can’t always recognise good stuff until you’ve had it pass through your hands.

Mr Sawyer would go through the auction catalogue of books and mark how much you were to bid and send you off to Sotheby’s. You had to stay on the ball, because sometimes he’d make an agreement with other booksellers not to let him get a lot below a certain price, because he’d be bidding for a customer and he’d be on commission. In those days, it was possible to make living by frequenting Sotheby’s and buying books. You learn a lot about the peculiarities of the bookselling trade. I think I was earning fourteen pounds a week. It was positively Dickensian.

By then I had met my wife Jeanna. We got married in 1965 and moved around between lots of flats we couldn’t afford. Jeanna & I started a book stall in Camden Passage called Icarus. I love the street markets like Portobello and Brick Lane. We made a lot of sales and I bought some wonderful stuff in street markets when you could discover things, and I’ve still got some of it.

We had two daughters, Samantha & Natasha, but Jeanna died young. We were living in Islington in Highbury Fields and I was left on my own to bring up the kids, who were eight and three years old at the time. That’s when I got this council flat, on account of being a single parent, and I’ve been here thirty-eight years. I lived on benefits with bookselling on the side to bring in some extra money and brought up my kids with the help of girlfriends.

A friend of mine had a secondhand tool shop and I worked there for a while. You could buy old tools from the sixteenth and seventeenth century for not very much money then, and we had some that no-one ever wanted to buy, so I brought them home. I am fascinated by tools for specialist professions, each one opens a door to a particular world. I still have my father’s furriers’ tools and they pack into such a small box.

From then on I’ve been a book dealer. Once you fall out of having a regular job, it’s difficult to go back. I think my kids regard me with mixture of mild disappointment and tolerance. On occasion, they have generously put up with me spending money on books instead of dinner.

I’ve always been a collector, reference books mainly, and from there I’ve become a dealer. I’m not interested in fiction but I do love a good reference book.”

Sawyer, the bookseller in Grafton St where Mike Henbrey once worked

Mr Gibbs, bookshop manager

![]()

GLOSSARY

by Spitalfields Life Contributing Slang Lexicographer Jonathon Green

Mike Henbrey, Collector of books, ephemera and tools

Mike Henbrey’s Vinegar Valentines have been purchased by Bishopsgate Institute where they are preserved in the archive as the Mike Henbrey Collection

You may like to take a closer look at some of Mike Henbrey’s collections

Mike Henbrey’s Vinegar Valentines

Vinegar Valentines for Bad Tradesmen