Oranges & Lemons Churches

First published in 1722, there has been enormous speculation around the identity of the churches in ‘Oranges & Lemons.’ But since St Clement’s Eastcheap once stood in close proximity to St Martin Ongar within an area traditionally inhabited by moneylenders in the City of Lond0n, I deduce these are the two churches featured in the opening lines.

From here, the locations spiral out and around the City like a peal of bells blowing on the wind. The third line refers to St Sepulcre-without-Newgate which stands opposite the Old Bailey and close to the location of the Fleet Prison where debtors were held. The fourth line features St Leonard’s, Shoreditch, while the church in the fifth line is St Dunstan’s, Stepney, and rhyme culminates back in the City of London at St Mary-le-Bow, Cheapside.

St Clement’s, Eastcheap

“Oranges and lemons,” say the bells of St. Clement’s

Site of St Martin Orgar, Martin Lane

“You owe me five farthings,” say the bells of St. Martin’s

St Sepulchre-without-Newgate

“When will you pay me?” say the bells of Old Bailey

St Leonard’s, Shoreditch

“When I grow rich,” say the bells of Shoreditch

St Dunstan’s, Stepney

“When will that be?” say the bells of Stepney

St Mary Le Bow, Cheapside

“I do not know,” says the great bell of Bow

You may also like to take a look at

The Cries Of Old London

My CRIES OF LONDON exhibition designed by Adam Tuck at Bishopsgate Institute closed yesterday, so I am publishing some of the panels from the show today for those who were unable to visit. Meanwhile, there are just a few tickets left for my illustrated lecture at Wanstead Tap on Tuesday 9th February. (This event is now sold out but I will be giving a lecture at the National Portrait Gallery in the summer at a date yet to be announced.)

(Click on this image to enlarge and read the text)

(Click on this image to enlarge and read the text)

(Click on this image to enlarge and read the text)

(Click on this image to enlarge and read the text)

(Click on this image to enlarge and read the text)

(Click on this image to enlarge and read the text)

(Click on this image to enlarge and read the text)

(Click on this image to enlarge and read the text)

(Click on this image to enlarge and read the text)

CLICK TO BUY A SIGNED COPY OF CRIES OF LONDON FOR £20

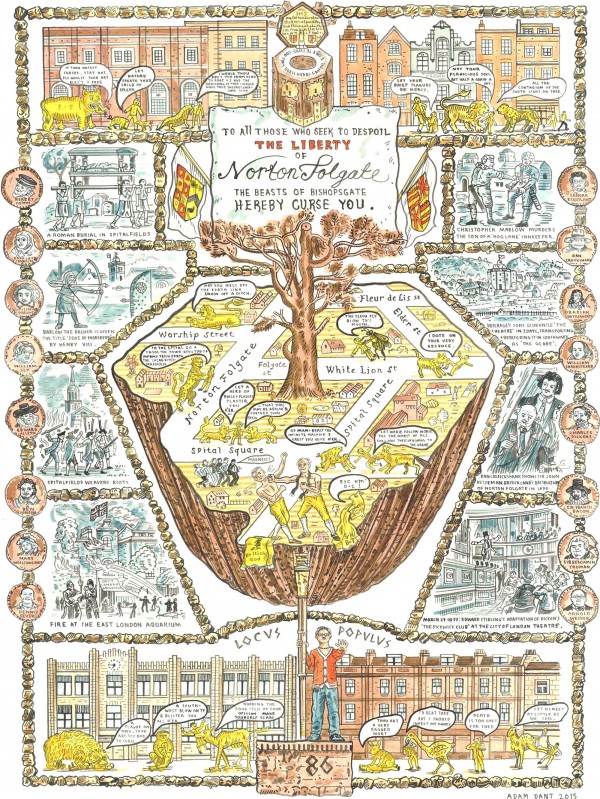

Beware The Curse Of Norton Folgate!

Click on Adam Dant’s map to enlarge

After Henry VIII destroyed the Priory of St Mary Spital, the Spanish Mystic, Dona Luisa de Carvajal y Mendoza who resided in Spital Sq, placed a curse upon anyone who might seek to despoil Norton Folgate in future and this week the ancient curse is making itself felt.

Ever since Boris Johnson waved through British Land’s proposal to obliterate Norton Folgate under a hideous corporate plaza last week, there has been a cloud of gloom hanging over Spitalfields, as downcast residents trudge the streets with their eyes to the pavement and hands deep in pockets.

No-one was surprised when the Mayor overturned the Council’s unanimous decision in favour of the developer, since he has done it a dozen times before, yet everyone was sickened by his vanity and the British Land executives high-fiving each other in the chamber once they got their desired result.

But yesterday there was a sudden break in the cloud, as the joyous news circulated that The Spitalfields Trust has been granted a Judicial Review to challenge Boris Johnson on of each of the four grounds upon which they believe the Mayor erred in law by intervening in the Norton Folgate case in favour of British Land’s plans to destroy more than 70% of the fabric of their site in a Conservation Area.

As our shameless Mayor approaches the end of his tenure, we await the full hearing at the High Court in the Spring – but in the meantime you can read the full text of the Judicial Review documentation by clicking here.

Boris Johnson & British Land, Beware the Curse of Norton Folgate!

Adam Dant is producing a limited edition of thirty copies of his Map of Norton Folgate at £500 each – sized 30” x 22” and all hand-tinted by the artist. Contact AdamDant@gmail.com for purchase enquiries.

You may also like to read about

At The London Chest Hospital

Plans for the future of the former London Chest Hospital next to Victoria Park are revealed at an exhibition which opens 3-8pm today and 10-2pm on Saturday at the Methodist Church in Approach Rd, Bethnal Green. Circle Housing bought the site from the National Health Service for forty-seven million pounds and we wait to see what their scheme will offer to the 22,000 families on the housing list in the borough – and whether the ancient Mulberry which bears the distinction of being the oldest tree in the East End will survive the redevelopment.

Thanks to an invitation from a reader last year, I had the opportunity of making the acquaintance of the oldest tree in the East End, a dignified tottering specimen known as the Bethnal Green Mulberry. Imported from Persia by James I in the sixteenth century, it is more than five hundred years old and once served to feed the silkworms cultivated by local weavers.

The Mulberry originally grew in the grounds of Bishop Bonner’s Palace that stood on this site and an inkwell in the museum of the Royal London Hospital, carved from a bough in 1915, has a brass plate engraved with the sardonic yarn that the Bishop sat beneath it to enjoy shelter in the cool of the evening while deciding which heretics to execute.

My visit was a poignant occasion since the Mulberry stands today in the grounds of the London Chest Hospital which opened in 1855 and closed forever last April prior to being put up for sale by the National Health Service in advance of redevelopment. My only previous visit to the Hospital was as a patient struggling with pneumonia, when I was grateful to come here for treatment and feel reassured by its gracious architecture surrounded by trees. Of palatial design, the London Chest Hospital is a magnificent Victorian philanthropic institution where the successful campaign to rid the East End of tuberculosis in the last century was masterminded.

It was a sombre spectacle to see workmen carrying out desks and stripping the Hospital of its furniture, and when a security guard informed me that building had been sold for millions and would be demolished since “it’s not listed,” I was shocked at the potential loss of this beloved structure and the threat to the historic tree too. So now we await the developers’ plans for this much-loved East End institution and, since the Mulberry is subject to a Tree Preservation Order, we hope this will be sufficient to save it.

Gainly supported by struts that have become absorbed into the fibre of the tree over the years, it was heartening to see this ancient organism renewing itself again after five centuries. The Bethnal Green Mulberry has seen palaces and hospitals come and go, but it continues to bear fruit every summer regardless.

The Mulberry narrowly escaped destruction in World War II and charring from a bomb is still visible

You might also like to read about

The Queen Mother’s Rebel Cousin

Roger Mills, author of Everything Happens in Cable Street, is currently researching the life of Lilian Bowes Lyon, a forgotten and barely-documented woman from an aristocratic background who committed herself to the East End in the Second World War. Some would describe her as ‘The Queen of the Slums,’ but Roger prefers to call her ‘The Queen Mother’s Rebel Cousin.’

This house at 141 Bow Rd is not remarkable other than because it survived Hitler’s Blitz and the ravages of post-war demolition, which saw traditional housing stock replaced with imposing tower blocks and maze-like estates. What is remarkable is the story of the woman who occupied this house during East London’s darkest hour. There is no plaque on the wall to tell her story to passers-by on the busy highway. There is no book to be read or documentary to be viewed. There is – in fact – very little of her story to be found anywhere. This is surprising, given her background, her voluntary and literary work, and her close connections to the Royal family.

One autumn day while wandering along the Charing Cross Rd, I noticed a slim volume of poetry in one of the second-hand bookshops. On seeing the cover I realised that the author, Lilian Bowes Lyon, must be part of the illustrious and well-known family of that name. What intrigued me was the title, Evening in Stepney. Stepney is my part of town. Why, I wondered, had the high-born poet chosen to write about East London? What I uncovered gave me some of the answers, none of which I expected.

Lilian was a first cousin of the Queen Consort of King George VI – better remembered today as that much-loved matriarch, the Queen Mother. Lilian was a novelist, poet and, at one point in her life, the mistress of the man who would go on to become Prince Charles’ personal guru-in-chief. Yet during the Second World War, despite being born into a wealthy and aristocratic family, she chose to work and live in the desperate, bombed-out streets of East London. Here, she befriended dock-workers and dustmen. Some would describe her as ‘The Queen of the Slums’ or ‘The Florence Nightingale of the East End.’ Yet today, she is totally forgotten. Over several decades of research into the history of East London, I have not found a single reference to her in many hundreds of histories, autobiographies and studies that I have read. Apart from one brief account, she appears only as a footnote in the histories of men. Am I alone in being curious that she remains an unknown figure?

Lilian Bowes Lyon was born, the youngest of seven, just before Christmas in 1895. Her parents were the Honourable Francis Bowes Lyon and Lady Anne Lindsay. As a child, she was waited on by servants at Ridley Hall in Northumberland and free to roam through acre upon acre of the estate’s dense woodland and landscaped gardens. She was five years older than her cousin, Elizabeth. Lilian joined the future Queen in Scotland’s Glamis Castle to help nurse injured servicemen when it was used as a convalescent home during the First World War. She later studied in London and at Oxford. She travelled extensively, spoke several languages and between the wars wrote two novels, the second under an assumed name. ‘Not because it was libellous or indecent or politically tendentious,’ her friend, William Plomer, wrote, ‘but because it did not conform to [her family’s] conventions either that she should write, or that she should write fiction, or that, if she did, she should write fiction suggesting that life was not a wholly comfortable proceeding.’

The books are those of a modern freethinker, with hints of taboo sexuality, and in The Spreading Tree, outright condemnation of a class-ridden England. Plomer wrote, ‘I used to tease her and call her a Bolshevik, but I am not sure that she was a political being at all… She was a poet with an acute response to the creative stirrings, however blind and dumb, of every human being.’ Lilian was ahead of her time – William Plomer’s homosexuality was fully accepted by her in a time of anti-gay prejudice, to the extent that she helped him financially to buy presents for his lovers. Bohemians’ begat beatniks begat Beatles and hippies. She never lived to see the sixties and the flowering of freedoms that she championed. But if she had, I like to imagine her, an eccentric old dame, turning up to do readings at basement jazz clubs, ‘happenings’ and Pop Art exhibitions. She was to be cheated out of that by a premature and tragic death.

The thirties saw her reputation as a poet grow with publications such as The White Hare, and Bright Feather Fading. That decade also saw her conduct an affair with the white South African adventurer, Laurens van der Post, nine years her junior and already married. Laurens would become a household name in later years, beguiling the Prince of Wales and the television viewing public with his tales of encounters with the Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert and his wartime experiences as a Japanese prisoner of war.

Lilian became a member of the Women’s Voluntary Service before the outbreak of war and assisted in the evacuation of the capital’s children to the countryside. She also guided bombed-out and traumatised Stepney children to the Hampstead War Nursery, partly run by Anna Freud, daughter of Sigmund. But her main association with the East End was to begin in a most unlikely place.

The Tilbury Shelter was formed from the arches, vaults and cellars of the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway goods station and an adjacent eight-story warehouse. Not being fully underground, it made a strange refuge from the bombs of the Luftwaffe. Yet every night it was bursting at the seams with East Enders desperate to escape the raids. At the start of the Blitz, the Tilbury was run by two separate bodies. On one side, vaults requisitioned by the borough council were authorised for shelter use. The connected warehouse site, however, was still being used as storage space. When bombing began it became clear that the vaults would not contain the numbers trying to get into them, and consequently the desperate crowd – aided by members of the local Communist Party – broke into the restricted area. Evidence indicates that it was occupied by up to 16,000 people every evening.

In all the shelters there was concern about the spreading of disease – scabies, impetigo, tuberculosis, diphtheria – and there were reports of lice. But anecdotal and official sources indicate that the Tilbury was the most filthy and disgusting of them all. ‘Hell Hole’ was a common description for it. There were just twelve chemical toilets in a curtained-off area, with some overflowing buckets for the children. As cold as the night might be, the temperature would rise, bringing about a foul stench from thousands of bodies who lacked any washing facilities. And at the heart of it, a mountain of rancid margarine, abandoned when the warehouse was overrun.

Lilian was a regular in the shelter, probably taking refuge when carrying out her work and, given her position in the WVS, almost certainly assuming a supportive role there. Eventually, the soiled margarine was removed and a clean-up operation begun when the situation – and the stench – could no longer be tolerated. So notorious was the Tilbury that it became a sort of subterranean cause celèbre, with artists such as Henry Moore and Edward Ardizzone joining the crowds. Also documenting the scene was the self-taught Rose L. Henriques, wife of Basil Henriques, founder of the local Oxford & St George’s Jewish Boys’ Club. Although she is known for philanthropic work, Rose’s paintings are less well remembered.

During 1942, Lilian Bowes Lyon came to live in Bow and composed her epic poem, Evening in Stepney. A brief entry about Lilian’s time here appears in The Queen Mother’s Family Story, written by James Wentworth Day and published in the sixties. It contains an interview with Lilian’s wartime housekeeper, Ellen Beckwith. Ellen recalls a royal visit – ‘The Queen Mother came one day. No fuss. She had a cup of tea with Lilian in the flat, and Lilian told her just what we needed down here,’ Other anecdotes feature the Duke of Kent dropping by and Lilian summoning Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, to Bow Rd to ‘give him a good talking-to and just show him what Bow needs.’ Lilian supposedly obtained a direct line to the Queen’s rooms at Buckingham Palace to berate one of the ladies-in-waiting for lack of free food and hot drinks during the VE Day celebrations. Ellen also recounts an incident of how during a bomb blast, Lilian was kicked in the leg by a hysterical woman. The inference is that the injury exacerbated a long-term diabetic condition. Lilian was resident in Bow until at least February 1945, but when her physical condition deteriorated she found herself swept back into the world of privilege she had attempted to escape.

I tracked the locations of Lilian’s life – the site of Tilbury Shelter, 141 Bow Rd, the series of West London houses where she spent her last days recovering from a series of grisly operations and her final dwelling in luxurious Brompton Sq. In constant pain, with both legs amputated, Lilian passed away there in the summer of 1949, yet continued to write her poetry until the end.

Later, I made a pilgrimage to the place of her birth in Northumberland and her final resting place. I was granted access by Durham University Library to her handwritten letters to William Plomer. Perhaps the most significant discovery I made was an article – she refers to it as a ‘letter’ – that William urged her to write about her time in, as she calls it, ‘dock-back-street-canal-and-sewer-land.’ The piece remains unpublished since it appeared in 1945. In it, she writes passionately about the lie of the ingrained class system in the ‘Two Nations’ of England and how social change could come swiftly, ‘if the whole lot of us faced the lie as we have faced the War.’

Her focus was the hardship faced by ordinary working class people, especially women and children. ‘The synthesis Marx had in mind, the social re-organisation on a higher level … depends on children,’ she wrote. ‘In one district here, where the Great North Sewer comes out, a district of gluey canals, of grinding machinery, of smells that are sour or sweetish according to which factory’s boilers were last cleaned, there is a children’s play-centre, where I often go, because it helps me believe that even the grimiest cocoon can’t kill the spirit of man. Except for this little centre … the children have nowhere to play, except the street. No room at home, often two large families divide the home between them, rents being high and the shortage of accommodation acute.’

The ‘letter’ tantalisingly refers to a diary kept by Lilian. It would be a fascinating read, possibly containing more of her views on politics, her local contacts and of another affair that she conducted with a married Jewish doctor while in East London. What happened to the diary on her death? Enquiries made to the highest family in the British social scale have brought about the reply that no archive relating to Lilian Bowes Lyon exists. The Royal circle tend to keep their secrets. I wonder if because of her left-leaning views, her romances, her circle of outsiders and her questioning of the accepted social order, Lilian is one of those secrets?

Lilian Bowes Lyon remembered outside the house where she lived 1942-45

Roger Mills at 141 Bow Rd

An extract from

EVENING IN STEPNEY

by Lilian Bowes Lyon

The circle of greensward evening-lit,

And each house taciturn to its neighbour.

The destruction of a city is not caused by fire;

What many have lost begets a ghostlier heritage

Or hails the unknown horizon; workaday street

A travel-ordained encounter, the breakable family

Fortified in defeat by the soldering air.

The destruction is in the rejection of a common weal;

Agony’s open abyss or the fate of an orphanage,

Mass-festering, mass-freezing or mass-burial,

Crime’s worm is in ourselves

Who crumble and are the destroyer.

Time to repair the infirmary soon, for tissue torn;

To plan the adroit, repetitive memorial.

The Tilbury Shelter, bombed second time, by Rose Henriques, 1941

The Tilbury Shelter in Stepney by Edward Ardizzone, 1941

The Tilbury Shelter in Stepney by Henry Moore, 1941

You may also like to read about

In The Debtors’ Cell

Walking into a cell from an eighteenth century prison in Wellclose Sq was an especially vivid experience for me because – if I had lived then – I and almost everyone I know would have invariably ended up in here at some point. Although almost nothing is known of the occupants of this cell, they created their own remembrance through the graffiti they left upon the walls during the few years it was in use, between 1740-1760, and these humble inscriptions still recall their human presence after all this time.

No one could fail to be touched by the emotional storm of marks across the walls. There are explicit names and dates carved with dignity and proportion, and there are dozens of crude yet affectionate images, presumably carved by those who could not write. There are also a few texts, which are heartbreaking in their bare language and plain sentiment, such as “Pray Remember the Poor Deptors.” The spelling of “deptors” after the model of “Deptford” is a particularly plangent detail.

About six feet wide and ten feet long, with a narrow door in one corner, and lined with vertical oak planks, this is one of several cells that once existed beneath the Neptune public house. There is a small window with wide bars, high upon the end wall, corresponding with street level – not enough to offer a view, but just sufficient to indicate if it was daylight. There would have been straw on the floor and some rough furniture, maybe a table and chairs, where the inmates might eat whatever food they could afford to buy from the publican, because this was a privately-managed prison run for profit.

Wellclose Sq was once a fine square between Cable St and the Highway, which barely exists any more. St Peter’s School, with its gleaming golden ship as a weathervane, is the only building of note today, though early photographs reveal that many distinguished buildings once lined Wellclose Sq, including the Danish Embassy, conveniently situated for the docks. When the Neptune was demolished in 1912, two of the cells were acquired by the Museum of London, where I was able to walk into one to meet Alex Werner the curator responsible for putting it on display. “We’re never going to know who they are!” he said with a cool grin, extending his arms to indicate all the names and pictures that people once carved with so much expense of effort, under such grim conditions, to console themselves by making their mark.

It is a room full of sadness, and even as I was taking my photographs, visitors to the museum came and went but did not linger. In spite of their exclamations of wonder at the general effect of all the graffiti, people did not wish to examine the details too closely. The lighting in the museum approximates to candlelight, highlighted some areas and leaving others in gloom, so I took along a flashlight to examine every detail and pay due reverence to the souls who whiled away long nights and days upon these inscriptions.

In a dark corner near the floor, I found this, painstaking lettered in well-formed capitals, which I copied into my notebook, “All You That on This Cast an Eye, Behold in Prison Here Lie, Bestow You in Charety.” The final phrase struck a chord with me, because I think he refers to moral charity or compassion. Even today, we equate debt with profligacy and fecklessness, yet my experience is that people commonly borrow money to make up the shortfall for necessary expenses when there is no alternative. I was brought up to avoid debt, but I had no choice when I was nursing my mother through her terminal illness at home. I borrowed because I could not earn money to cover household expenses when she lived a year longer than the doctors predicted, and then I borrowed more when I could not make the repayments. It was a hollow lonely feeling to fill in the lies upon the second online loan application, just to ensure enough money to last out until she died, when I was able to sell our house and pay it off.

So you will understand why I feel personal sympathy with the debtors who inhabited this cell. Every one will have had a reason and story. I wish I could speak with Edward Burk, Iohn Knolle, William Thomas, Edward Murphy, Thomas Lynch, Richard Phelps, James Parkinson, Edward Stockley and the unnamed others to discover how they got here. In spite of the melancholy atmosphere, it gave me great pleasure to examine their drawings incised upon the walls. Here in this dark smelly cell, the prisoners created totems, both to represent their own identities and to recall the commonplace sights of the exterior world. There are tall ships with all the rigging accurately observed, doves, trees, a Scots thistle, a gun, anchors and all manner of brick buildings. I could distinguish a church with a steeple, several taverns with suspended signs, and terraces stretching along the whole wall, not unlike the old houses in Spitalfields.

I shall carry in my mind these modest images upon the walls of the cell from Wellclose Sq for a long time, created by those denied the familiar wonders that fill our days. Shut away from life in an underground cell, they carved these intense bare images to evoke the whole world. Now they have gone and everyone they loved has gone, and their entire world has gone generations ago, and we shall never know who they were, yet because of their graffiti we know that they were human and they lived.

You may also like to read about

Trinity Green Needs Friends

(Click this image to enlarge)

Trinity Green Almshouses in Mile End only survive because some illustrious friends saved these distinguished and benign examples of social housing, which were built at the end of the seventeenth century under the supervision of Sir Christopher Wren.

CR Ashbee, founder of the Guild of Handicrafts at Essex House, was so dismayed to see the destruction of a palace in Bow which once belonged to James I, he launched a campaign in 1895 to rescue Trinity Green Almshouses when demolition and redevelopment were suggested upon the implausible premise that it would be too expensive to repair the drains.

With the vocal support of William Morris, Octavia Hill, Lord Leighton, Walter Besant and many others, Ashbee succeeded in his goal and Trinity Green became the first historic building in the East End to be saved for posterity. As part of his campaign, he published a handsome monograph, surveying and recording the building in detail, from which the drawings here are reproduced. This monograph became the origin of the Survey of London which continues to this day.

Today, Trinity Green needs friends again to counter the neglect of the fabric of recent years and to challenge the development by Sainsbury’s which proposes a tower of luxury flats the height of Centrepoint overshadowing the almshouses. So please click here and sign up to become a Friend of Trinity Green and – by doing so – continue the work of CR Ashbee, William Morris, Octavia Hill, Lord Leighton, Walter Besant and all those involved at this crucial site for the Conservation Movement.

Already, as a consequence of the influence of the newly-formed Friends of Trinity Green, Historic England have written a letter of support which condemns the height of the Sainsbury’s luxury block and challenges Tower Hamlets Council with a Public Enquiry if they approve the current plan.

CR Ashbee, saviour of Trinity Green – drawing by William Strang in 1903

Trinity Green seen from the Master’s House

Retired naval gentlemen in the club room at Trinity Green

Statue of Captain Richard Naples

Elevation on Mile End Rd

A game of draughts

Model ship from the frontage on Mile End Rd

Model ship from the frontage on Mile End Rd

Cat at the foot of the statue of Captain Maples

The current Master & Commander at Trinity Green

Sainsbury’s proposed tower of luxury flats

Click here to learn more about the FRIENDS OF TRINITY GREEN

You may also like to read about