Doreen Fletcher’s East End, Then & Now

Recently, Contributing Photographer Alex Pink accompanied Doreen Fletcher on a pilgrimage to visit the locations of many of her paintings and Alex photographed what they discovered …

Benji’s Mile End, 1992

Mile End church seen from the park, 1986

The Albion Pub, 1992

Snow in Mile End Park, 1986

Park with train, 1990

Limehouse library, 1986

Shops in Commercial Rd, 2003

Terrace in Commercial Rd under snow, 2003

Brickfields Gardens, 1986

Grand Union Canal, 1983

Hairdresser, Ben Jonson Rd 2001

Rene’s Cafe, 1986

Bus Stop, Mile End, 1983

The Condemned House, 1983

Caird & Rayner Building, Commercial Rd, 2001

Paintings copyright © Doreen Fletcher

Photographs copyright © Alex Pink

Doreen Fletcher’s exhibition LOST TIME opens on Friday 10th June at Townhouse, 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields and runs daily until 26th June

You may also like to take a look at

Robert Green Of Sclater St Market

One afternoon recently, over a couple of drinks in the quiet back bar at The Carpenters Arms in Cheshire St, Robert Green told The Gentle Author the epic story of his family’s involvement in the market through three generations and over almost a century

Robert Green – My connection to the Sclater St Market goes right back to my father’s father, Edward Green, who started down here in the twenties. He used to sell bird seed. In those days, it was a big animal market and pigeons were the number one thing. Every man in the East End used to levitate his way down towards Club Row, as it was known then. So my grandfather ended up down here selling bird seed on a regular basis and, as soon as he was old enough, Ronald, my father – who was born in 1921 – started coming down here with him too. My grandfather was in the Coldstream Guards. He got wounded and sent to the military hospital at Woolwich. After he came out of there, he began trading down the market on Sundays.

In the thirties, my father started thinking about market trading himself but he did not join the animal market, he decided to go into clothing – which we are still doing today, selling a few socks and things like. He traded all through the war and I remember him telling me about the first time they had an air raid siren – he said he had never seen the market pack up so fast, everyone was gone in about ten minutes.

After the war, a lot of buildings had gone. That plot behind my stall where the ‘Avant Garde’ Tower is now was one big wasteland. A lot of people set up stalls on that piece of ground. The owners of the properties had not got any war damage compensation, so no one really planned to do anything. It was just left as wasteland and people started trading there, which was how my father ended up on a bomb site. He traded there from 1948 until the mid-fifties, which is when we got the licence in the market. He had been applying for the licence all that time while he was working in a menswear shop in Green St during the week and trading on Sundays, until he got prosecuted for illegal trading– a five pound fine and ten shillings cost. Finally in 1955 – just before I was born – he managed to get a licence. A pitch became available and the council offered him a permanent licence, so he took that.

The Gentle Author – Why did it take so long to get a licence?

Robert Green – You simply could not get a licence in those days, it was such a busy market that there was literally no space. All the pitches were taken. Nowadays it is easy to forget, but relatively recently – from pre-war days up to the fifties, even the early seventies – on a Sunday, you go could down your local high street and hear a pin drop. There was nothing open. If you wanted to go anywhere and do any shopping or look around, the only place to go on a Sunday morning was down the market. In Tower Hamlets, on Sunday there was Petticoat Lane, Club Row and Columbia Rd. Virtually all the men in the local area used to make their way towards Club Row Market because it was the place to be on a Sunday morning. It was always known as a local market, whereas Petticoat Lane was a bit touristy, attracting people from far and wide.

The Gentle Author – My parents went to Petticoat Lane on their honeymoon in 1958.

Robert Green – Imagine someone saying that now! “I’m taking you to Petticoat Lane for your honeymoon,” I do not think it would go down too well. Incredible when you think how times have changed. Down here in Club Row, it was mostly pets and birds in particular. If you look at any photos from the fifties and sixties or earlier, nine out of every ten people would be men. Very few women used to come down, it was always known as a man’s market mostly because of the association with birds, which were an exclusively masculine interest in those days.

Originally we had one pitch from which we traded all through the forties and fifties. By the late fifties, my father had made a little bit of money in the market so he managed to acquire the shop in Upton Park which acted as a base.

The Gentle Author – Your grandfather was dealing in bird seed, why do you think your father switched to shirts?

Robert Green – When my father left school, he started working in a pawnbrokers at Canning Town and they used to deal in a certain amount of clothing. Then he got a job in a department store near Canning Town called ‘Stabbings’ and he worked in menswear. Then he transferred to another one at Upton Park – ‘Woodmanses,’ which had a menswear department too. Finally, he ended up working in a menswear shop next to the Odeon at Upton Park. It was called ‘Finkles’ and my dad worked for the Jewish man that ran it for ten years, so he built up a background in clothing. When he eventually got his own shop in Green St, it took off because he became an agency for a lot of big firms – Fred Perry, Raelbrooks – all the top names of the time. That enabled him to have a fantastic trade because a lot of shops could not even get those brands, so having them in a market put him streets ahead of everybody else. By the sixties, we had two stalls in the market. We had two vans and two drivers – on an average Sunday we had about six people working on our stalls.

The Gentle Author – Was a lot of this clothing manufactured locally?

Robert Green – In those days, it was all manufactured in England and a lot of them were London-based firms. Raelbrooks was in Walthamstow and Fred Perry’s factory was up in Tottenham. Double Two was a Wakefield shirt company, they had two factories – Barnsley and Cleckheaton – up in Yorkshire. We used to go there two or three times a year, once we could buy a lot of stock. In the market, it used to be absolutely phenomenal. During the sixties, when I was still at school, I was down here every Sunday and I spent all morning wandering round the market. Then I came back and spent a few hours sitting under the stall in a cardboard car, eating sweets.

The Gentle Author – What were your first impressions of the market?

Robert Green – I thought it was incredibly exciting, I could not wait to get down here every Sunday even though I was only about ten years old. You could find stalls for everything under the sun.

In those days, every Sunday was like Wembley at Cup Final – you had to push your way through the crowd, shoulder to shoulder. We used to have them about five or six deep round our stall. If you walked away from the stall, you could not get back, it was be so crowded. It was an absolute magnet. I have seen people fighting over a yard of space because they did not have enough room for their stall. It was so crowded you would not believe it. Now you could drive a bus through here and it would not touch anything.

There were so many characters too. Going to the market in the fifties and sixties was like street theatre. Even if you did not want to buy anything, you could spend the morning being entertained because all the stalls had characters who had their own routines.

Beside our pitch we had two brothers – they used to sell crockery, tea sets and china. They started off by spreading out this massive tea service, cups on top, saucers, and they would have the whole thing piled up with about fifty pieces of china. Eventually, they would throw the whole lot up in the air, crash it down onto the stall and shout out a price. I must have seen them do that thousands and thousands of times, but I never once saw them break anything. It was a real skill, there was an art to it. As a boy, I used to be fascinated, standing there for ages watching them over and over again, waiting for them to drop something, but they never did.

There was an elderly man with his daughter who stood one stall away from us, they sold that white paste you clean cookers with, which gets the grease off and grime. It was his own concoction because in those days there was no real consumer legislation. I remember his daughter. She was probably in her thirties and she looked like a film star, always very glamorous – the most unlikely person you could imagine on a market stall. She had bright blonde hair, always wore bright red lipstick and she dressed very smart.

They took it in turns to demonstrate and he would get these old grimy cooker pieces out, spread this stuff on, then give you the spiel and, after a few minutes, magically wipe all the dirt off and it would be beautiful and clean. Then, to demonstrate how safe it was, he would put his finger in the tin, scoop a dollop out and clean his teeth with it, to show that – no matter what you did – it was not going to do you any harm. I used to stand there for hours and hours watching. Almost every other stall had someone doing this type of thing. It was a day out.

On the other hand, I have mixed feelings about the animal market because I am a passionate supporter of animal welfare. There were genuine people but I would not dispute there were also a lot of unscrupulous people who attached themselves to it as well. You did get a lot of things going on that should not have been allowed and, during the eighties, the animal rights campaigners began arriving each week, so eventually it got outlawed and you could no longer trade in animals. It did have a massive effect on the market because probably a third of the people who used to go down there only went for the animals, so that was a real turning point.

In one way, I am glad the market changed but there were a lot of innocent victims who got pushed out at the same time. Palmers’ pet shop, for example, established over a hundred years. I knew Mr Palmer well, his father had been there since the turn of the nineteenth century. They spent all week bagging up birdseed and, on Sunday, the whole lot would go out in one morning. There used to be a queue of people outside right up until they closed at two o’clock in the afternoon. In the late eighties, Mr. Palmer retired and a West Indian who was running the place for him took over the business until redevelopment forced him out. I still keep in touch with him, he is back in Trinidad now but he phones up occasionally.

The Gentle Author – Do you remember the Bishopsgate goods yard fire?

Robert Green – It was on a Saturday night. We used to go out for walks after the shop closed and we had been out one Saturday night when we came home and it was on the newsreel. My father looked up and my mother said, “There’s a big fire up in Shoreditch somewhere, it’s on the news now.” My father said, “Ere, that’s the goods yard! What’s going to happen to the market? It’s coming up to one of the busiest times of the year – we won’t be able to trade tomorrow.” It was in the run up to Christmas 1964. My father said, “This is one of the busiest days of the year – it’s a disaster!” On Sunday morning, we set off as usual but we could not get anywhere near Sclater St. There were firemen everywhere. The whole of Sclater St was covered in fire hoses, they had the road blocked off. My father said, “Oh this is terrible, we’re going to lose a whole day’s trading.”

There were twice as many people there as normal, because you had all the usual market crowd plus a lot of others who had watched the news and come to see what had happened. By around ten o’clock, the fire was over apart from trails of smoke here and there, so the fire brigade decided to clear the hoses and the police let us down Sclater St.

In those days, the market inspectors were very strict. They came round at one o’clock and that was the end of trading. They all looked like Blakey out of ‘On the Buses,’ they had long trenchcoats and peaked caps and they would come round with a clipboard, very stern. “One o’clock, stop trading, stop serving, start packing up!” So at ten o’clock we only had three hours to trade, yet that turned out to be one of the busiest Sundays we ever had. I remember my father telling me we were so busy that he had to send one of the drivers back in the van to the shop to get more stock. Yet, although it was a disaster that turned out to be an amazing success from a business point of view, I cannot forget the people who lost their lives in that fire – a customs officer and a railway worker.

That fire transformed the place and it never really got back to normal. Thousands and thousands of people used to be in and out of the goods yard all the time but, after the fire, it made the area desolate during the week. From Monday to Saturday, you would see nobody you knew. Eventually they pulled the goods yard down but in the meantime the market had got to the stage where, over thirty years after the war, it was the same as it had been since the bombs dropped. I remember there were old burnt out cars abandoned on the bomb site and, where the cellars once were and they had levelled it off, the ground dipped down. I used to play and lark about over there. All through the seventies, the bomb site was full of stalls, there was literally hundreds and hundreds of stalls, and that created a massive uplift in the market because it had almost gone to four times its size. It all merged into one and we probably did more trade in the seventies than during the fifties and sixties.

The Gentle Author – By this point, you were running the family pitches?

Robert Green – I was coming up to leaving school and my father did not even ask me, he just assumed that I would start working for him, so in 1971 when I left at the end of the summer term, he said, “You have a couple of weeks off and then you can start working for me.” So I had two weeks’ holiday – I did not go anywhere, I was just loafing about – and then I started working in the shop and, from then on, I was in the market every Sunday serving on the stalls with my sister Pat.

I was only a teenager but I had new ideas and, after a year or two, when I had found my ground, I started to put more and more into the business and we began to build it up, so by the mid-seventies we were doing more trade than ever. We drove down here with two big vanloads and came back with virtually nothing. We used to have a little crowd of people waiting for us when we arrived at the stall. People used to come up and say, “Give us one of them in white, blue, cream, in this size,” and that was it, a dozen at a time.

In the late seventies, there was a period of rapid inflation. We were putting up prices four or five times a year and that was reflected in lower sales, and we got into a vicious spiral. Then the animal market went and there was a 50% drop in our business. By then the trading laws had changed, so the market was no longer the place to be on a Sunday morning because the high streets shops were open too and there were car boot sales opening all over the place.

We kept going because it is what we do but we got rid of one of the pitches. We were back to where started yet, although the trade was not there and we were not making money any more, I do not ever remember my father even vaguely suggesting that we might not be there. Whether the trade was there or not, he still had the same attitude.

Since 1971, I have only missed seven Sundays. Six of those were in 1976 when I broke my leg and could not walk, and the other one I had to miss because the licence was being changed into my name and the council stopped me trading for a week. I ignored it and went down there but, the following week, they came up and said, “If you’re here next week, we’re going to prosecute you because you’re not allowed to be here.” I still went down there actually but I was not trading.

In 1996, my father went to hospital and they said, “You’ve got cancer and there’s nothing we can do about it,” and they gave him six months to live. As it happens he went on for just over a year. He still kept going down the market but, when it came to the last few months, he got pretty bad and he could not. He had been here every Christmas since the nineteen-twenties when he used to come down with his father. He was very sick but he said to me, “I want to go down there for the last Sunday’s trading.” I told him, “You can’t go down there dad, you can’t hardly walk ,” but he said, “I want to go down there.”

So, on the last Sunday’s trading before Christmas, me and Pat came down here and traded as we always do and packed up a little bit early and went back. By the time I got back to the shop it was four o’clock in the afternoon. I brought him downstairs and into the car. I drove him back up there to market and I said, “Well come on then, obviously you’ve missed the day, but you can still say you’ve actually been here for the last Sunday.”

By the time I got him here and parked up near our pitch, everybody had gone. It was raining, so it was wet, cold and windy and he was in a terrible state. I got him out of the car and walked him over and he stood on the pitch. We both stood there and neither of us said anything but I knew he was thinking the same as me, he was running through in his mind all the years he had been standing there. We stood for about ten or fifteen minutes looking up and down the road. Neither of us said a word, and then eventually I said, “Come on dad, you can’t stay here now, it’s cold and it’s wet.”

I walked him back and got him into the car and then, after almost seventy years of being down here every Sunday, he left Sclater St for the last time and two weeks after that he was dead, just after Christmas.

I thought to myself, “What he would want me to do? He would want me to prove myself, prove my own worth, that I could do just as much as he did.” So I threw myself into the work wholeheartedly. I was working twenty hours a day in the shop. I was there until one o’clock in the morning unpacking stock. I was out all the time going round wholesalers and suppliers. For a year or two it paid off. We ended up doing as much trade as we used to do years ago but then, because I was successful at it, I found did not want to do it anymore. I had proved that I could, I had been as successful as he had. I had fought against adversity but I did not see any point in carrying on and I started to get a few health problems.

I went to my doctor and he said to me,“You’re going to have to make radical changes because you’re heading for catastrophe.” I had never had a holiday since I was ten years old when my father took me to Torquay. That was the only holiday I ever had, but even then it was only Monday to Saturday, because we had to go on Monday and come back on Saturday so we did not miss the market on Sunday. My doctor said to me, “You’re not that young any more” – by that stage I was nearly fifty – “You can’t do a hundred hours a week.”

We were getting a lot of problems in the shop – burglaries and robberies all the time – things had totally transformed in Upton Park. We had to keep the door locked during the day even though the shop was open. So it was a choice – either the market or the shop. There was no way I could lose the market, so I discussed it with my sister and we decided to sell the shop. Since fifty, I have gone into sort of semi-retirement and at the end of this year I will be sixty. I do not think I would be here now if I had not taken my doctor’s advice because I could not have carried on like that. After I sold my father’s shop, I was wracked with guilt for three or four years but I am sure I made the right choice.

We have not made any money in the market for the last four or five years and most weeks it costs me money to be here, but I do not care. I am coming down here because it is where we have always been, it is tradition. I know everybody down here – it is like a social club more than anything.

To a lot of people, the market is like a family, they feel comfortable down here. You get those who are on the fringe of society, they do not really fit in elsewhere, these people seem to levitate towards it because they feel comfortable here. These days you hear so much about community spirit but they do not know what they are talking about. Having a shiny block of flats is not generating community spirit, it is completely missing the point. What is going on down here in the market and what has happened in the past, that really is a community spirit. People feel comfortable, they feel that they are part of something and when they are not here they feel as if they are on the outside looking in at everybody else but they love it in the market because they really feel this is where they belong, you know.

Transcript by Rachel Blaylock

Ronald Green trading in shirts in the fifties

Ronald sells shirts on a bomb site in Sclater St in the fifties

Ronald Green’s shop in Upton Park

Robert Green outside L&S Bird Stores in Sclater St in the seventies

Robert minds the stall as a youngster in the seventies

Ronald & Robert Green in Sclater St in the eighties

Robert & Patricia Green in the eighties

Patricia & Robert Green selling shirts on Sclater St today

You may also like to read about

Doreen Fletcher’s Exhibition

Just over six months ago, I introduced you to Doreen Fletcher’s paintings in these pages and I am thrilled to announce that – thanks to the extraordinary positive response by you, the readers of Spitalfields Life – Doreen’s first solo exhibition of these works opens next Friday 10th June at Townhouse, 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields, and runs until 26th June.

Hairdresser, Ben Jonson Rd, 2001

It is my pleasure to publish this selection of the remarkable paintings and drawings created by Doreen Fletcher in the East End between 1983 and 2003.

“I was discouraged by the lack of interest,” admitted Doreen to me plainly, explaining why she gave up after twenty years of doing this work. For the past decade, all these pictures have sat in Doreen’s attic until I persuaded her to take them out and let me photograph them for publication here.

Doreen came to the East End in 1983 from West London. “My marriage broke up and I met someone new who lived in Clemence St, E14,” she revealed, “it was like another world in those days.” Yet Doreen immediately warmed to her new home and felt inspired to paint. “I loved the light, it seemed so sharp and clear in the East End, and it reminded me of the working class streets in the Midlands where I grew up,” she confided to me, “It disturbed me to see these shops and pubs closing and being boarded up, so I thought, ‘I must make a record of this,’ and it gave me a purpose.”

For twenty years, Doreen conscientiously sent off transparencies of her pictures to galleries, magazines and competitions, only to receive universal rejection. As a consequence, she forsook her artwork entirely in 2003 and took a managerial job, and did no painting for the next ten years. But eventually, Doreen had enough of this too and has recently rediscovered her exceptional forgotten talent.

Many of Doreen’s pictures exist as the only record of places that have long gone and I publish her work in the hope that she will receive the recognition she deserves, not just for outstanding quality of her painting but also for her brave perseverance in pursuing her clear-eyed vision of the East End in spite of the lack of any interest or support.

Bartlett Park, 1990

Terminus Restaurant, 1984

Bus Stop, Mile End, 1983

Terrace in Commercial Rd under snow, 2003

Shops in Commercial Rd, 2003

Snow in Mile End Park, 1986

Laundrette, Ben Jonson Rd, 2001

The Lino Shop, 2001

Caird & Rayner Building, Commercial Rd, 2001

Rene’s Cafe, 1986

SS Robin, 1996

Benji’s Mile End, 1992

Railway Bridge, 1990

St Matthias Church, 1990

The Albion Pub, 1992

Turner’s Rd, 1998

The Condemned House, 1983

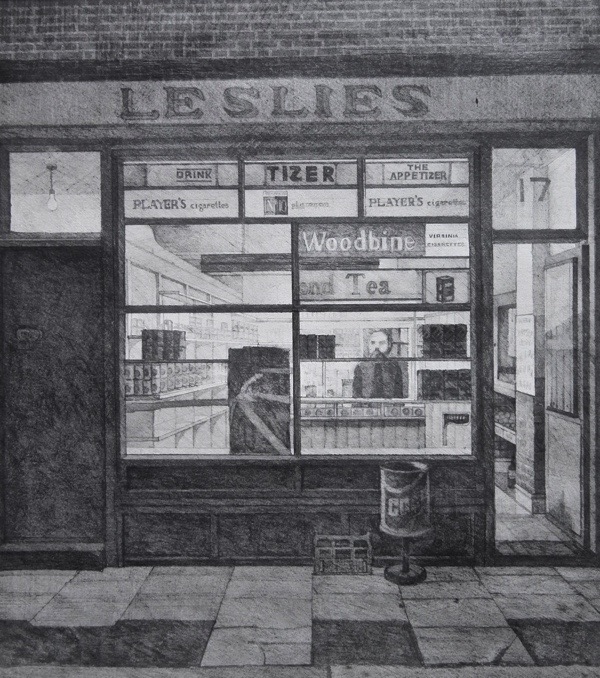

Leslie’s Grocer, Turner’s Rd, 1983 (Pencil Drawing)

Newsagents, Canning Town, 1991 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Bridge Wharf, 1984 (Pencil Drawing)

Pubali Cafe, Commercial Rd, 1990 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Ice Cream Van, 1990 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Turner’s Rd, E3

Palaseum Cinema, Commercial Rd

Salmon Lane in the Rain, 1987

Mile End Park, 1987

Wintry Park, 1987

Limehouse Churchyard, 1987

Stepney Snooker Club, 1987

Stepney Snooker Club, Evening, 1987

Commercial Rd, 1989

Railway Arch, Bow

Images copyright © Doreen Fletcher

You may also like to take a look at

John Claridge’s People On The Street

Tonight, Friday 3rd June, John Claridge will be talking about his EAST END photography with Stefan Dickers at 7pm at WATERSTONES PICCADILLY, W1J 9HD. Email piccadilly@waterstones.com to reserve your free ticket.

We shall be giving away posters of John Claridge’s photograph of Sammy Fisher’s Grocery Shop to all comers!

Brick Lane 1966

“Sometimes there is no reason, but you have to do it and that’s what makes magical things happen.” photographer John Claridge said, introducing this set of pictures,“There is no why or wherefore of doing it, because it’s not from the head – it’s from the heart.”

I took John’s declaration as a description of his state of rapture as he wandered the pavements of the East End to take these photographs of people on the street, going about their daily lives.“I used to get up early and walk around,” he confided to me and I understood the sense of loneliness that haunts these evocative pictures, in which the subjects appear distant like spectres, self-absorbed and lost in thought.

“The important word is ‘request'” said John, speaking of the photo of the man at the request bus stop, “He’s in some kind of world that we are not party to.” In John’s youthful vision – enthralled by the writing of Franz Kafka – the East End street became an epic stage where an existential drama was enacted, peopled by characters journeying through a strange landscape of forbidding beauty.

John knew he was photographing a poor society within a poor environment, but he was a part of it and held great affection for it. “Just another day of people walking around,” he concluded to me with uneasy levity – emphasising that while these images are emblematic of a world which time may have rendered exotic, it is also world that was once commonplace to him.

Whitechapel, 1960

Whitechapel, 1981.

E13, 1962 -“This was taken from my window at home.”

Spitalfields, 1962 – “They look like they are up to no good.”

Whitechapel, 1968 -“Where did the boy get that peaked cap?”

Spitalfields, 1961. -“An old man stops to light up.”

Spitalfields, 1961 – “A moment, a story in itself.”

Whitechapel, 1982

Spitalfields, 1982 – “I walked past her and just grabbed the picture as I went by.”

Spitalfields, 1962

Spitalfields, 1968 – “The dog is looking at the rubbish in exactly the same way as the man is looking at the rubbish.”

At the ’59 Club, 1973

Weavers’ Fields, 1959 An old lady walks across a bombsite in Bethnal Green.

Whitechapel, 1964

E16, 1964 –“The important word is ‘request.’ He’s in some kind of world that we are not party to.”

Whitechapel, 1982

E16, 1982 -“He’s going home to his dinner.”

Princelet St, 1962 – “Just a man and a pigeon.”

Spitalfields, 1968 -“I like the shadows, where they’re falling.”

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

John Claridge’s Time Out

Join me tonight, Thursday 2nd June at the BOOK LAUNCH PARTY for John Claridge’s EAST END from 6pm upstairs at THE FRENCH HOUSE, 49 Dean St, Soho, W1D 5BG. We are giving away posters of Sammy Fisher’s Grocery Shop to all comers!

Tomorrow, Friday 3rd June, John Claridge will be talking about his EAST END photography with Stefan Dickers at 7pm at WATERSTONES PICCADILLY, W1J 9HD. Email piccadilly@waterstones.com to reserve your free ticket.

Cornerman, E17 1982.

“People take time out of their lives in all kinds of ways, so I thought I’d explore the spectrum of the things people used to do,” John Claridge told me, outlining his rationale in selecting this contemplative set of pictures. Each shows a moment of repose, yet all are dynamic images, charged by the lingering presence of what came before or the anticipation of what lies ahead.

While the photograph of the Cornerman above literally shows“time out” at a boxing match, John was also interested in the cross-section of people watching and taking a breather from their working lives. “With a boxing ring, you’re wondering what’s going to happen. You’re waiting for the episode.” he admitted, “I like that tension and quietness, knowing that you’re going to get boxers flying around the ring in a few minutes.”

Similiarly, speaking of his photograph below of the pub compere, John said to me, “You can’t see anyone on the stage but you know something’s going to happen. I like it that people have to contribute to the picture, it takes you into another environment. You have to enter another world. You have to ask questions.”

John’s pictorial frame equates to the boxing ring or the pub stage, encompassing a space through which life passes – but his is an arena of calm within the relentless clamour of existence, a transient place of both photographic and emotional exposure.

Time out!

End of the Game, E14 1962 – “When the churchyard was dug up, someone arranged the stones respectfully so they could be seen. Life was over and even the churchyard was gone too.”

Sunday Morning, Spitalfields 1963. “He was leaning out the window having a conversation, it just felt like Sunday morning.”

The Allotment, E14 1959.

Soup Kitchen, Whitechapel 1967. “Time out for a cup of tea and a sandwich, time out from the streets.”

Passports, E16 1968.

Game at the Hostel, Salvation Army Victoria Homes, Whitechapel 1982.

The Conversation, 1982.

Underworld, public toilet outside Christchurch Spitalfields 1982.

Pub Compere, E14 1964.

My Dad Singing At a Pub, E14 1964. – “He had a good voice, very powerful, and he used to play the ukelele banjo as well. My mum got up and sang too. He’d say, ‘Don’t be silly, you can’t sing.’ and she’d say, ‘Yes, I can,’ and get up there. They had a fantastic relationship.”

The Ring, E17 1982.

Wraps, E16 1968. “This is at Terry Lawless’ Gym. I still have a punchbag at home and start by putting my wraps on.”

After Sparring, E16 1968. – “He had just finished, marked up a little but not too bad.”

Dance Class, E7 1982. – “Did people go to learn to dance or because they were lonely?”

Dog Racing, Walthamstow Dog Track 1982.

Some Were Got Rid Of. – “It still looks like it’s running.”

Dart Night, E17 1968. – “We were playing darts and sat down for a break, everyone in their own world. The guy with the sideburns, his wife was jealous and always asked him to bring her a Chinese takeaway. He would remove the prawns, eat them himself and then rearrange the food. ‘She’s not worth all those,’ he said to me. ‘She won’t know,’ I said. ‘She’ll never know, but I do,’ he replied.”

Some People I Knew, Cable St 1969.

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

CLICK HERE TO ORDER YOUR COPY OF EAST END FOR £25

Pick up your free poster of Sammy Fisher’s Grocery Shop from The French House tonight

Last Saturday, I published Paul Gardner’s story of Sammy Fisher of Old Montague St but since then Barbara Holland has managed to uncover more of the long journey that led to his photographic encounter with John Claridge in 1961.

Sammy Fisher’s story is similar to that of many Jewish families who made the East End of London their home in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I have put together a picture of just a small part of his life, and hopefully answered one or two questions from Paul Gardner’s account of his friendship with Sammy.

Sammy Fisher was born Samuel Fischhoff in Kingston Upon Hull on 19th October 1908, son of Josef and Rose Fischhoff. His father, Josef, an egg merchant, was born in 1883 in Galicia, a region of Austria which suffered extreme poverty in the nineteenth century. This forced hundreds of thousands of people to leave the area in order to survive, many choosing to start a new life in another country. So Josef would have been one of these many migrants who eventually made their way to Hull.

Hull was a prominent destination for migrants heading from Eastern Europe. It is estimated that 2.2 million people passed through the Emigration Platform at Hull’s Paragon Station up until 1914, about a half million of whom were Jewish. The city had a thriving Jewish community at the beginning of the twentieth century which would have provided support to the migrants. Although most people were in transit, heading for America, Canada, Brazil or South Africa, some – like Josef – chose to stay.

There is no record for Josef (or Joseph) in the 1901 census, so he probably arrived after this year. He applied for naturalisation to become a British citizen and this was granted on 15th October 1909. By this time, he had married Rose Gelman in 1905, who was born in Russia, and they had four children – Israel Solomon who was three years old, Benjamin a one year old, and twins Jacob and Samuel, eight months old. So we now know that Sammy had a twin brother, Jacob, as well as two older brothers – but Jacob died in 1929.

By 1911, Josef and Rose had another son, Isaac, born in 1910 and they were living at 46 Norfolk St, Sculcoates in Hull. They went on to have a total of fourteen children, with Alexander (born 1912), Chaim (1913), Chaiena D. (1914), Elsie (1916), David (1917), Harris/Harry (1919), Alter (1921) Daniel (1924), and Leizer/ Leslie (1925). All survived to adulthood except Chaim and Chaiena.

Sammy’s father ran the family business importing eggs, originally in partnership with Lionel Isaac Robin and then on his own, until his sons were old enough to join. By the nineteen-thirties, the family had egg importing businesses in Tooley St, London and in Manchester as well as Hull. Joseph’s original business in Hull, now described as egg & china merchants, went bankrupt in 1941, but the others continued in business under the management of his sons.

At some point, Sammy made the move to London. The first record I can find is a marriage between Samuel Fischhoff and Bertha Richer in 1934 in Hackney. Bertha was the daughter of Joseph and Jane Richer (previously Reicher), the youngest of eleven living children. They were also from Galicia in Austria, the same region as Sammy’s parents, although they came over in the eighteen-eighties and settled in Whitechapel. By 1911 they were living in Dalston.

In the Electoral Register for 1936, Sammy and Bertha are living at 17 Tallack Rd, Leyton, but have the shop at 92 Old Montague St in Whitechapel. In the 1938 Post Office Directory, Samuel Fischhoff is now listed as an egg merchant & salesman at number 92. Going back to the 1934 directory, number 92 was being run by a Miss Hetty Handler (or possibly Kandler), egg merchant. So it looks as if he took over the shop between 1934 and 1936 as a ‘going concern,’ probably to sell eggs as part of the family business. Phone books for the period 1936 to 1949 have S. Fischhoff, Grocery Provisions, listed at number 92.

The Electoral Registers for 1939 and 1948 lists Samuel and Bertha as living at 6 Evelyn House, Greatorex St, just around the corner from number 92. I can find no record of them having any children.

I had almost given up trying to track Sammy and his wife after 1949 as they did not appear in any records, including death records. This was because they changed their surname – mysteriously not to ‘Fisher’ (as he told Paul Gardner), but to ‘Franklyn.’ Armed with this information, I established that they continued to live in Evelyn House until at least 1983, probably until Sammy died in early 1984. I believe Bertha died soon after in 1986 in Southend, although I cannot be absolutely certain.

And what of those well-off Manchester relatives who turned up at Sammy’s funeral in a Rolls Royce? At least two of his brothers, Isaac (d. 1985) and David (d.2000) survived him. David Fischhoff had a china & glass business in Manchester which is still going, now selling ‘memorial, floral, giftware and home décor.’ Another brother, Alexander, had been an egg merchant and then a china merchant in Manchester as well. So there was probably some wealth from these business interests that meant they could afford a Rolls Royce to go to the funeral. With such a large family, other relatives may also have attended, and some of them may have memories of Sammy and his family to share.

John Claridge’s Moments Of Connection

Join me tonight, Wednesday 1st June for the EXHIBITION OPENING of John Claridge’s EAST END photography from 6pm at VOUT-O-RENEES, 30 Prescot St, Aldgate, E1 8BB. (Exhibition runs until 21st July)

Tomorrow, Thursday 2nd June is the LAUNCH PARTY for John Claridge’s EAST END book from 6pm upstairs at THE FRENCH HOUSE, 49 Dean St, Soho, W1D 5BG.

This Friday 3rd June, John Claridge is talking about his EAST END photography with Stefan Dickers at 7pm at WATERSTONES PICCADILLY, W1J 9HD. Email piccadilly@waterstones.com to reserve your free ticket.

Self-Portrait with Keith (standing behind with cigarette), E7 (1961).

“We still meet up for a drink and put the world to rights.”

Here is the young photographer John Claridge at seventeen years of age in 1961, resplendent in a blue suede jacket from Carnaby St worn with a polo neck sweater and pair of Levis, and bearing more than a passing resemblance to the character played by David Hemmings in ‘Blow-Up’ five years later.

On the evidence of this set of photographs alone it is apparent that John loves people, because each picture is the outcome of spending time with someone and records the tender moment of connection that resulted. Every portrait repays attention, since on closer examination each one deepens into a complex range of emotions. In particularly intimate examples – such as Mr Scanlan 1966 and the cheeky lady of 1982 – the human soul before John’s lens appears to shimmer like a candle flame in a haze of emotionalism. The affection that he shows for these people, as one who grew up among them in the East End, colours John’s pictures with genuine sentiment.

Even in those instances – such as the knife grinder in 1963 and the lady on the box in Spitalfields 1966 – in which the picture records a momentary encounter and the subjects retain a distance from the lens, presenting themselves with a self-effacing dignity, there is an additional tinge of emotionalism. In other pictures – such as the dance poster of 1964 and the windows in E1 of 1966 – John set out to focus on the urban landscape and the human subjects created the photographic moment that he cherished by walking into the frame unexpectedly. From another perspective, seeing the picture of the mannequin in the window, we share John’s emotional double-take on discovering that the female nude which drew his eager gaze is, in fact, a shop dummy.

For John, these photographs are not images of loss but moments of delight, savouring times well spent. If it were not for photography, John might only have flickering memories of the East End in his youth, yet these pictures capture the people that drew his eye and those that he loved half a century ago, fixing their images eternally.

Across the Street, E1 (1982) – “I did a double-take when I first saw this. In fact, it was a mannequin in the window. Still looked good.”

School Cap, Spitalfields (1963) – “I just found this surreal. It was as if the man behind was berating a nine-year-old who couldn’t care less.”

Two Friends, Spitalfields (1968) – “They were walking along sharing one piece of bread.”

The Box, Spitalfields(1960) – “I came across this lady sitting on an orange box, there was nothing else around. Then she got up and walked off with her box.”

Labour Exchange, E13 (1963) – “Never an uncommon sight.”

Ex-Middleweight Boxer, Cable St (1960) – “We were talking about boxing when he just gave me the thumps-up.”

Knife Grinder, E13 (1966) – “Every few weeks he would appear at the end of the street. Quite a cross-section of people had their knives sharpened!”

Mr Scanlon, E13 (1966) – “My next door neighbour. Always with a wicked sense of humour and an equally wicked smile.”

The Doorway, E2 (1962) – “To this day I would still like to know where her thoughts were.”

Crane Driver, E16 (1975) – “He could balance a crushed car on half a crown and still give you change.”

59 Club, E9 (1973) – “The noise of the pinball machines with the sound of the jukebox playing Jerry Lee.”

A 7/6 Jacket, E13 (1969) – “He had a small shed where he sold anything he could find, which he collected in a small handcart.”

A Portrait, E1 (1982) – “This special lady asked me ‘Why do you want to photo me?’ I replied ‘Because you look cheeky.’ This is the picture.”

Scrap Dealer, E16 (1975) – “This was shot in Canning Town, near the Terry Lawless boxing gym.”

The Step, Spitalfields (1963) – “A kid at play.”

Dance Poster, E2 (1964) – “I was taking a picture of the distressed posters when he glided past.”

The Windows, Spitalfields (1960) – “Behind every window.”

My Mum & Dad, Plaistow (1964) – “Taken in the backyard.”

Fallen Angel, E7 (1960) – “There were a lot of fallen angels in the East End.”

Photographs copyright © John Claridge

CLICK HERE TO ORDER YOUR COPY OF EAST END FOR £25

John Claridge’s East End Landscapes

Join me tomorrow, Wednesday 1st June, for the opening of the exhibition of John Claridge’s EAST END photography from 6pm at VOUT-O-RENEES, 30 Prescot St, Aldgate, E1 8BB. (Exhibition runs until 21st July)

This Thursday 2nd June, there is a book launch party for John Claridge’s EAST END from 6pm upstairs at THE FRENCH HOUSE, 49 Dean St, Soho, W1D 5BG.

On Friday 3rd June, John Claridge is talking about his EAST END photography with Stefan Dickers at 7pm at WATERSTONES PICCADILLY, W1J 9HD. Email piccadilly@waterstones.com to reserve your free ticket.

My Backyard, E.13 (1961) by John Claridge

“My bedroom and darkroom. What more could you want? Somewhere to get your head down. Somewhere to get your print down.”

When William Wordsworth was growing up, he had an overwhelming epiphany of the power of the landscape while out in a boat upon Grasmere beneath a starry sky, and photographer John Claridge had an equally influential experience at a similar age – in a very different kind of environment – while out on a night’s ratting expedition at a piggery next to the London Docks. “There was the glow of the lights of the dock, but all around us were vast expanses of darkness,” he told me in his excitement at recalling the wonder of the East End during his childhood in the nineteen-fifties, in the days before the halogen glow which obscures the stars today.

“It was a different kind of landscape – without fields – but it was a landscape I loved, the landscape I grew up with,” John confessed, remembering the acres of bombsites and craters, wasteland and allotments that he once knew, and which he recorded in these pictures. “When I was fifteen, I was interested in motorbikes, girls and photography, though I couldn’t say in what order,” he admitted to me with a laugh.

There is a certain cast of occluded light shared by many of these photographs that is partly the result of the London smog of that era, partly mist off the river and partly the light of the early morning when John delighted to explore the East End. “I’m still an early riser, from the days of getting up at five to do my paper round.” he explained, “I’d have breakfast with my dad and listen to his stories – that was my education – then I’d cycle around in the dawn delivering papers before school each morning. You always expected something to happen, but you had to let it happen – that was part of the excitement of seeing something that you weren’t expecting to see, and then you wanted to share it.”

In the post-war East End, prior to redevelopment, the open spaces created a landscape of possibility where nature thrived, where anyone could have an allotment, and where John liked to go scrambling on his motorbike. It was a landscape that offered emotional freedom and creative space to John, who as a fan of Dan Dare and Flash Gordon, was off on his own imaginative journey.

Ultimately, it was John’s talent that took the young photographer on a journey far from his native landscape, giving him a career filled with globe-trotting assignments. Today these early pictures record a place that no longer exists except as a personal landscape of memory. They show how the first landscape that met John’s eyes became the landscape upon which his vision as a photographer was shaped. And it is an epic landscape.

East End Blossom, E.1 (1960). “Blossom on a bomb site.”

Canning Town Bridge in the Fog, E.16 (1965). “Shot from my motorbike (Triton) – stopped, of course.”

Sewer Bank Rd, E.13 (1964). “My house was just over the fence to the right.”

Ford & Vauxhall, E.15 (1960). “Turner Prize?”

Clearing a Bomb Site, E.13 (1961). “The next street to where I lived.”

Iron Bridge, E.16 (1964). “An iron bridge across the railway line, not far from the docks.”

The East End Horse, Allen Gardens, Spitalfields (1972). “The horse takes a break from the harness of a dray cart.”

Smoke, E.16 (1963). “Winter’s morning looking towards Canning Town. I used to take my old scrambler motorbike and ride the bomb craters there.”

Vicky Park, E.3 (1962). “Where I used to take the occasional girlfriend.”

Canal, E.3 (1968). “Early morning, grey day but full of expectation.”

After the Rain, E.16 (1982). “That beautiful smell after everything’s had a good wash.”

Scrap Yard, E.16 (1982). “Sometimes it got muddy.”

The Path, E.7 (1960). “Neglected cemetery, always so quiet.”

Allotments, E.6 (1963). ” This area always had a strange presence, a symbiosis between industrial and natural.”

The Small Creek, E.3 (1987). Daybreak.

Along the Track, E.16 (1973). “Shot from a parapet, early morning above the rail-track. I wanted a bit of height.”

Rooftops, E.3 (1982). “There was always a great man-made sculpture around, not to every one’s taste but I liked it.”

Slag Heaps, E.6 (1963). “This area seemed to always have a greyness that sat in the sky.”

Spillers, E.16 (1987). ” I loved these buildings, it was like walking into an early sci-fi movie.”

Photographs copyright © John Claridge