Fresh Fish For Passover In Stamford Hill

At nine o’clock yesterday morning, a tanker of fish pulled up at the kerb outside Hoffman’s Fish Shop in Stamford Hill, where a small crowd of families had already gathered in keen expectation of its arrival. They were seeking live salmon and trout to cook for Passover. Each customer had a plastic bin lined with a black bag and they stepped forward in turn to select live fish decanted in nets from the truck into tanks on the pavement.

The nature of the season, the splashing of the water and the liveliness of the fish engendered an infectious excitement as occasionally a large salmon made a leap for freedom onto the pavement, engendering shrieks of delight from the younger members of the congregation. Yet before long, everyone had acquired the requisite number of salmon and trout necessary to feed their family and relatives, and set off for home with their bags of fish still twitching in anticipation of Passover.

You may also like to read about

At Chu’s Garage

Quang Chu of Chu’s Garage

Chu’s Garage under the railway arches in London Fields has become a reliable institution among motorists in Hackney over the last thirty years for good service and honest dealing. Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I met the Chu family while making a survey of the small independent businesses under the arches which are currently being threatened with excessive rent increases up to 300% by Network Rail, and we decided to return to hear the Chu’s story.

In the middle of the day at Chu’s Garage, work ceases and a ring is attached to a gas bottle for Jimmy Chu to cook a fresh lunch, which the family eat around the table in the cosy hut, complete with an altar, which serves as their dining room.

Sarah & I were honoured to be lunch guests and afterwards, over cups of green tea, we learnt of the astonishing story that lies behind Chu’s Garage. This was an unexpected epic, the dramatic tale of the Chu family’s perilous journey from Viet Nam to Britain, revealing their remarkable hard work, courage and tenacity in pursuit of a new life, which culminated in opening their beloved garage.

Chuong Kim Chu in Hai Phong, Viet Nam, 1974

Nhi Chu – My father, Chuong Kim Chu, was Chinese but he was born in 1935 in Viet Nam. My grandfather had come from Quanzhou in the south of China and migrated with his brothers to Viet Nam. So my father married my mother, Lien, who was Vietnamese and, although we grew up knowing that my dad was Chinese, we did not speak Chinese until we came to the refugee camp in Hong Kong.

Quang Chu – I remember when I was small my grandfather tried to speak Chinese with us. At that time, Viet Nam and America were at war and, many times by day and by night, they were bombing the city where we lived. It was very scary but interesting for a child. At night I saw the rockets and they were colourful, like fireworks. I remember the sound of the aeroplanes and fire everywhere. The table and chairs shook! Many times we were evacuated from the city to escape the bombs.

Chau Chu – One day my mum said there was a siren and, as we didn’t have a shelter, she went to the neighbours and asked ‘ Can we please come in to your shelter?’ But they said, ‘We’re so sorry, there’s no space.’ So my mum took us somewhere else and later that day, when we came back, we found our neighbours’ house had been bombed and everyone killed.

Nhi Chu – When my father grew up in Viet Nam, the family were poor so he didn’t go to school but he taught himself to read and write, Vietnamese and Chinese. He said, he learnt by eavesdropping on classrooms. When my father was seven, my grandfather, who was a herbalist, saved someone’s life and in return they said, ‘Your son can come with me and I will give him an education.’ But, one night, my father wet the bed and was so scared that he would be beaten up that he ran away, and that was the end of his education. When he was thirteen, he became an apprentice in the engine room on a big passenger ship. He had such a curious mind that, when the captain went away, he took an engine apart and memorised how it fitted together. But when he put it back he forgot one piece, so when the captain returned he got a whack over the head.

Chau Chu – We never saw our father much because he was always away from home as a long distance lorry driver. Whenever it broke down, he could fix it himself. That was how he started as a mechanic. The company gave him the lorry and he had to look after it. He saved up a long time to buy his truck, yet when the Communists took over they just took it from him.

Nhi Chu – During the war with America, Viet Nam and China were on good terms but, after the war ended the two countries fell out over a border dispute. At that time, there was a campaign by the Vietnamese government to get all Chinese migrants and their descendants to leave the country, and they were as hostile to them as they possibly could be. People started to lose their businesses. My mother said that my father was being subjected to a lot of abuse at work, from his colleagues who had once been his friends. He was quite a popular person and every year when they had the competition to see whose lorry was in the best condition, my dad always won the first prize. But then the tables turned and he had his truck taken away, so he no longer had his business or customers. My father knew that he had to leave because he was no longer able to make a living.

Meanwhile, my mother was being bombarded by people saying, ‘Leave your husband! He’s Chinese, you are Vietnamese. If he goes to China, you should stay here because you will be abused there.’ So there was a conflict, but my mother decided she wanted to stay with her husband and children. As children, we felt we were Vietnamese, we didn’t know we were Chinese, we didn’t make the distinction.

Chau Chu – All of a sudden, people were pointing at us and saying, ‘You are Chinese, you don’t belong here!’

Quang Chu – When we got to Hong Kong, they spoke Cantonese and we had to start everything from the beginning. Everything was very hard for us.

Chau Chu – We were forced to leave Viet Nam, we had no choice. We didn’t go to Hong Kong right away, we just wanted to leave the hostile environment of Viet Nam.

Nhi Chu – Because my father was Chinese, the Chinese government gave him visas and papers to go to China legally and we travelled from Viet Nam to China by train. We lived there for a year but the problem was that, although my dad was accepted as Chinese and got a job as a lorry driver, my mother and us kids were not accepted. We were city folk but we were sent to the mountains and every day we were given a portion of a field and had to turn it into fertile soil. Unfortunately, my mother looks Vietnamese and she was subjected to a lot of abuse from the locals. She had no choice but to hide inside the house. My dad realised this was no way to live and no future for us children. We couldn’t stay and he knew he had to find a new territory where all of us could live together peacefully.

We left China illegally because in those days no-one was permitted to leave. We couldn’t all leave in one go, so we divided the family. The plan was for our elder brothers Quang and Jimmy to leave to Hong Kong and make some money and send it back, and then the rest of us would join them there.

Quang Chu – The sea was very rough and lot of people died. The old boat was rotten and leaked inside, and it was overloaded. There were more than two hundred people, old and young and even babies just born. All kinds of people but all seasick. It was their first time ever on a boat. This was a short distance but a long journey, very long. Suddenly the sky might turn dark with thunder and lightning, heavy rain and strong wind – oh, it was scary. It was only a few days but the captains were inexperienced and they went round and round. We were lucky we survived the sharks but a lot of people didn’t.

Nhi Chu – We waited but we didn’t hear anything from them for six months and then a year.

Quang Chu – We sent them letters but they didn’t get them.

Nhi Chu – My dad decided that we couldn’t wait and we needed to go. We left at night but we had to make the house look as if we were still living there, because if the police found out they would come and stop us. For about a week, we were stranded at sea and then we got to Hong Kong.

Chau Chu – They hated us as well because we wanted to come onto their small island. They wouldn’t let our boat land, it was only when it was sinking that they picked us up. They had to check we were not from China, because if they knew we were from China they would send us back, so we had to say we had come from Viet Nam.

Nhi Chu – For two nights, we were on the boat and there was a storm which hit our boat and it began to sink, which is why they took us on board. For two weeks, we were held in a Forbidden Camp, where you can’t get out of, and then we were released to a Freedom Camp. We were waiting to be allocated a sleeping area when we saw my brother Jimmy. He came with Quang and we asked, ‘Still alive! How come you didn’t write to us?’ They explained that they had to get rid of all their paperwork at the border, so they lost the address and every day for a year they took turns to come to the camp to see if we were there. Finally, we were reunited but we found out that if we had been a month later we should have missed Quang and Jimmy, because they had already decided to go to America.

My dad didn’t want to go America, he wanted to come to England because he had been told that they treat old people very nicely here. He said, ‘I’m going to be old one day.’

Quang Chu – He said, ‘Why don’t they say ‘Speak American’? – they say ‘ Speak English.’ So he thought England must be a very good country, better than America.

Nhi Chu – That was 1979 and Mrs Thatcher announced she would accept ten thousand Vietnamese refugees, so we among the first batch. We came to England in 1980 and we first settled at the refugee centre in Dorchester for ten months where we started learning English.

Quang Chu – We went to the sea at Bridport, it was very nice.

Chau Chu – There were about fifteen families and we were happy there. Each of the families took turns cooking. Then we were resettled in Barrow-in-Furness and all the racism started again, like in Viet Nam.

Nhi Chu – We had been sheltered in Dorset but then suddenly we were the only Vietnamese family in Cumbria. It was back to square one, and we couldn’t find work so Quang had to move to Wigan and Jimmy to Bournemouth.

Quang Chu – Barrow-in-Furness is a very small town where everyone works at the shipyard and that only offers enough jobs for the local people, so we had to go elsewhere. But I think it’s good to see other places and other ways of life. You learn a lot when you have to stand on your own two feet, facing life.

Nhi Chu – After five years, we moved south.

Quang Chu – I think my father had decided that Barrow was good enough for him, but then he met so many people in London.

Nhi Chu – Even though my father was in his late forties by then, he managed to pick up the English language. He continued to attend evening classes after the rest of the family stopped and, after about a year, he managed to get a job at the local garage in Barrow. When he went for an interview, the manager just said, ‘Here’s a car, tell me how many faults you can find with it.’ When he came back, the manager said, ‘There should be eleven,’ and my father said, ‘I found thirteen’ – and that’s how he got the job. Dad worked there for three years to get his qualification and then he was promoted to foreman, but he had such a hard time because the other younger mechanics resented him because of his age and race.

Chau Chu – He always knew that he would come to London one day to set up a garage.

Nhi Chu – One of his mottos in life was ‘Whatever anyone can do, the Chu family can do it just as good, if not better.’ We could never go to him and say, ‘Dad I can’t do that.’ He’d say, ‘What do you mean? You can’t yet!’

Chau Chu – He was fifty when he came to London.

Quang Chu – In 1985, he started across the road from here in a shed that he shared with a Turkish guy. There were holes in the ceiling, which made it very slippery when it rained. At that time, the railway arches were vacant and this was a very rough area.

Nhi Chu – After a year, quite a few people applied to rent this arch, but my father was lucky and he was successful. The rent was between five and six thousand annually then.

Quang Chu – We moved in here in 1988 and we fitted it ourselves but there was no business.

Nhi Chu – Bricks and cement fell from the arch whenever trains ran across. We contacted Network Rail but they ignored us for years and years.

Quang Chu – Business was very difficult, so my father decided to do MOT Class 7, vans and light commercial vehicles. There were so many garages doing MOT Class 4 but MOT Class 7 was very rare. In Hackney, we have not heard of anyone else doing it. So my father decided that doing Class 7 MOTs was the way to survive. There was so much regulation and red tape to get to be an MOT Station – but then we realised we had no MOT testing equipment! Everything for us for us was new. It was very scary.

Nhi Chu – Dad had to study the MOT textbook, the rules and regulations, and then he had to go and do a test. He really struggled, so he had to have the help of his old English teacher to translate all the terminology – and my dad passed.

Quang Chu – When we first became the MOT-nominated tester, we held a party and invited our old friends. It was very expensive to set up and we had to borrow money from so many people. The bank wouldn’t lend to us, so we had to do it Vietnamese style – we go to a lot of people, relatives, neighbours and friends, and borrow small amounts of money and keep a list. They said, ‘This is good for everybody, good for you and for the Vietnamese community.’ So we have tried to look after them and pay back everyone gradually.

Chau Chu – The MOTs have kept our business going, otherwise we would have shut down.

Quang Chu – We feel good about it – even Hackney Council bring their vans here for MOT.

Nhi Chu – When my dad died, we wanted to have a grave to represent his life, so we got a designer to come here and take a look at the garage. He said, ‘Howabout if we design it with an arch?’ My father used to say, ‘I spent all my time here, my blood and sweat to make this garage as it is, so when I die bury me in the maintenance pit.’ We achieved that in a way by creating a tombstone in the shape of an arch which he is now resting beneath.

When we start talking about our father, we realise what an amazing character he was. When he passed away, we had to tell the customers and some of them burst out crying. A lot of people miss him. Without his motivation, we would not have been able to bring the whole family from one country to another country. This garage is his legacy.

The Chus’ lunch cabin

Jimmy Chu cooks lunch

Nhi Chu

Chau Chu washes up

The Chu’s office

Nhi Chu

Chau Chu

Jimmy Chu

Quang Chu with his father’s toolbox

Quang Chu

Jimmy Chu

Chuong Kim Chu

Lien Chu

Chuong Chu standing in front of his trunk with Quang in Viet Nam, 1974

Chuong Chu standing in front of his trunk with Quang in Viet Nam, 1974

The Chu family reunited in Hong Kong 1979

Chu family in Barrow-in Furness

Chuong Chu at Chu’s garage

Mr & Mrs Chu outside Chu’s garage

Mrs & Mrs Chu upon their return to Viet Nam for their fiftieth wedding anniversary

New photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

The Pleasures & Miseries Of London

Written anonymously and published in 1820, The Tour of Dr Syntax Through the Pleasures & Miseries of London was one of a popular series of comedies featuring the idiosyncratic Dr Syntax, a character originated by William Coombe and drawn by Thomas Rowlandson. These plates are believed to be the work of Robert Cruikshank, father of George Cruikshank.

Dr Syntax & his Spouse plan their trip to London

Setting out for London

Arriving in London

Robbed in St Giles High St

A Promenade in Hyde Park

A Flutter at a Gaming House

At an Exhibition at the Royal Academy

At a Masquerade

In St Paul’s Churchyard on a Wet & Windy Day

Inspecting the Bank of England

Presented to the King at Court

A Night at Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens

A Visit to the House of Commons

A Trip behind the Scenes at the Opera

A Lecture at the London Institution

Going to Richmond on a Steam Boat

Reading his Play in the Green Room

Overshoots London Bridge & pops overboard into the Thames

Images courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

More of Tom & Jerry’s Life in London

James Boswell, Artist & Illustrator

Today I feature James Boswell, illustrator of A HOXTON CHILDHOOD, whose drawings we have reproduced from the original artwork for the new edition (including A.S. Jasper’s sequel THE YEARS AFTER illustrated by Joe McLaren) which I am publishing this spring.

The launch party for A HOXTON CHILDHOOD & THE YEARS AFTER is on Tuesday 25th April 7pm at the Labour and Wait Workroom, 29-32 The Oval, Off Hackney Rd, Bethnal Green, E2 9DT. There will be live music, readings and refreshments. Click here for tickets

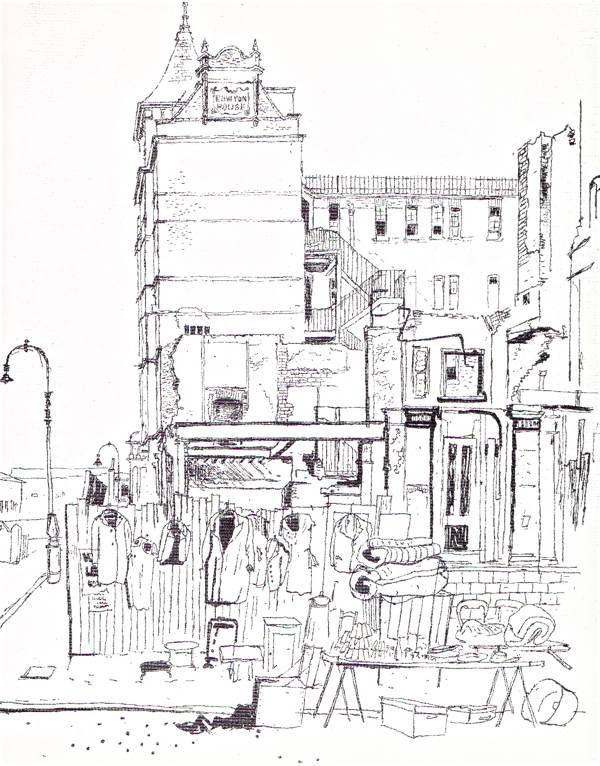

Drawing of Hoxton Market by James Boswell

A few years ago, I had the privilege of travelling up to a leafy North London suburb to meet Ruth Boswell – an elegant woman with an appealing sense of levity – and we sat in her beautiful garden surrounded by raspberries and lilies, while she told me about her visits to the East End with her late husband James Boswell who died in 1971. And when I left with two books of drawings by James Boswell under my arm as a gift, I realised it had been an unforgettable introduction to an artist who deserves to be better remembered.

Ruth is no longer with us. But this year I returned to that same North London suburb with designer David Pearson to meet James Boswell’s daughter Sal Shuel and enquire after his drawings for A.S Jasper’s A HOXTON CHILDHOOD. Thanks to Sal, we were able to photograph the original artwork of his illustrations and cover design, and reproduce them freshly in the new edition, A HOXTON CHILDHOOD & THE YEARS AFTER.

To introduce you to James Boswell’s work, I have selected these lively drawings of the East End done over a thirty year period between the nineteen-thirties and the fifties. There is a relaxed intimate quality to these – delighting in human detail – which invites your empathy with the inhabitants of the street, who seem so completely at home it is as if the people and cityscape are merged into one. Yet, “He didn’t draw them on the spot,” Ruth revealed, as I pored over the line drawings trying to identify the locations, “he worked on them when he got back to his studio. He had a photographic memory, although he always carried a little black notebook and he’d just make few scribbles in there for reference.”

“He was in the Communist Party, that’s what took him to the East End originally,” she continued, “And he liked the liveliness, the life and the look of the streets, and and it inspired him.” In fact, James Boswell joined the Communist Party in 1932 after graduating from the Royal College of Art and his lifelong involvement with socialism informed his art, from drawing anti-German cartoons in style of George Grosz during the nineteen thirties to designing the posters for the successful Labour Party campaign of 1964.

During World War II, James Boswell served as a radiographer yet he continued to make innumerable humane and compassionate drawings throughout postings to Scotland and Iraq – and his work was acquired by the War Artists’ Committee even though his Communism prevented him from becoming an official war artist. After the war, as an ex-Communist, Boswell became art editor of Lilliput influencing younger artists such as Ronald Searle and Paul Hogarth – and he was described by critic William Feaver in 1978 as “one of the finest English graphic artists of this century.”

Ruth met James in the nineteen-sixties and he introduced her to the East End. “We spent quite a bit of time going to Blooms in Whitechapel in the sixties. We went regularly to visit the Whitechapel when Robert Rauschenberg and the new Americans were being shown, and then we went for a walk afterwards.” she recalled fondly, “James had been going for years, and I was trying to make my way as a journalist and was looking at the housing, so we just wandered around together. It was a treat to go the East End for a day.”

Pennyfields

Rowton House

Old Montague St, Whitechapel

Gravel Lane, Wapping

Brushfield St, Spitalfields

Wentworth St, Spitalfields

Brick Lane

Fashion St, illustration by James Boswell from “A Kid for Two Farthings” by Wolf Mankowitz, 1953.

Russian Vapour Baths in Brick Lane from “A Kid for Two Farthings.”

James Boswell (1905-1971)

Leather Lane Market, 1937

Images copyright © Estate of James Boswell

You can see more work by James Boswell at www.jboswell.org.uk

You might also like to take a look at

In the Footsteps of Geoffrey Fletcher

The Most Famous Bells In The World

In the third of my series of the stories of Whitechapel Bells, I visit the Bow Bells in Cheapside

These are the bells of St Mary-le-Bow in the City of London which have good claim to be the most famous set of bells in the world, known as the Bow Bells. These are the bells that Dick Whittington heard in the fable, which seemed to call ‘Turn again Whittington, Thrice Lord Mayor!’ as he ascended Highgate Hill to depart the capital in 1392, inspiring his return to London to seek his fortune with the assistance of his celebrated cat. These are the bells that are so beloved of Cockneys that you must be born within the sound of Bow Bells to call yourself one of their crew. Naturally, these bells were cast at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, the most famous bell foundry in the world.

Simon Meyer, Steeplekeeper at St Mary-le-Bow had to ascend Christopher Wren’s magnificent tower to change the clock to British Summer Time recently, which afforded me the opportunity to accompany him and view the bells for myself. When we arrived in the belfry, Simon leapt happily around upon the frame as if it were second nature to him yet I found it necessary to place my feet a little more deliberately as we negotiated the famous bells. ‘They’re about to ring,’ he announced at one moment, which filled my head with alarming thoughts of bells rotating in their frames but in fact turned out to be a clock chime which did not entail any movement of bells. Occasioning a reverberation within the belfry as powerful as the sound itself, this is not something I shall forget in a hurry.

The earliest record of the Bow Bells is from 1469 when the Common Council ordered a curfew rung each night at 9pm, marking the end of the apprentices’ working day. In 1588, Robert Greene compared Christopher Marlowe’s poetry to the sound of Bow Bells when he wrote, “for that I could make my verses jet upon the stage in tragical buskins, every word filling the mouth like the faburden of Bow-Bell, daring God out of Heaven with that Atheist ‘Tamerlaine.'”

After the Great Fire, Christopher Wren rebuilt St Mary-le-Bow and the association with Whitechapel began in 1738 when Master Founder Thomas Lester recast the tenor bell. In 1762, he recast the other seven bells and added two more to make a set of ten that were first rung to celebrate George III’s twenty-fifth’s birthday.

In the twentieth century, the bells were restored by H. Gordon Selfridge, the department store entrepreneur, yet these were destroyed within eight years when the church was bombed during an air raid on May 10th 1941. Climbing the tower today, you are immediately aware that it is a reconstruction since the internal structure is of concrete, creating the strange impression of utilitarian bunker clad in seventeenth century stonework.

The current set of twelve bells were cast in Whitechapel in 1956 by Arthur Hughes, and Alan Hughes, the current Whitechapel Bell Founder, recalls being taken out of school for the day by his father to witness the casting. Every bell has an inscription from the psalms and the first letter of each spells out D WHITTINGTON.

It was the use of a 1927 recording of Bow Bells by the BBC during World War II that took them to the widest audience, broadcasting their sound to occupied countries across Europe as a symbol of hope. Even today, the sound of Bow Bells is broadcast globally as the interval signal by the BBC World Service, making these the most familiar bells on the planet. Bow Bells are the definitive London bells and the signature of the capital in sound.

FOUNDED BY ALBERT ARTHUR HUGHES OF THE WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY 1956

THE WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY LONDON

“‘I do not know,’ says the great bell of Bow’

The ringers’ chamber

St Paul’s viewed from the tower of St Mary-le-Bow

Erected in 1821, the Whittington Stone commemorates the spot on Highgate Hill where Dick Whittington heard the Bow Bells in 1392 and decided to return to London and seek his fortune

This sculpture of the cat was added in 1964

Sculpture of Dick Whittington and his cat at the Guildhall by Lawrence Tindall, 1999

St Mary-le-Bow, Cheapside, c.1900 (Courtesy Bishopsgate Institute)

You may also like to read about

A Visit To Great Tom At St Paul’s

A Petition to Save the Bell Foundry

Save the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

So Long, Whitechapel Bell Foundry

CLICK HERE TO SIGN THE PETITION

Henrietta Keeper, Singer

I am delighted to announce that my good friend Henrietta Keeper will be singing at the launch party for A HOXTON CHILDHOOD & THE YEARS AFTER on Tuesday 25th April 7pm at the Labour and Wait Workroom, 29-32 The Oval, Off Hackney Rd, Bethnal Green, E2 9DT. Click here for tickets

Friday is an especially good day to have lunch at E. Pellicci in the Bethnal Green Rd, because not only is Maria Pellicci’s delicious fried cod & chips with mushy peas likely to be on the menu, but also – if you are favoured – you may also get to hear Henrietta Keeper sing one of her soulful ballads. Celebrated for her extraordinary vitality, the venerable Henrietta (known widely as “Joan”) is naturally reticent about her age, a discretion which you will appreciate when I reveal that she is able to pass as one thirty years her junior.

Henrietta tucked into her customary fried egg & chips last Friday as the essential warm-up to her weekly performance while I sat across the table from her enjoying the cod & chips with mushy peas, and helping her out with her chips. “My husband died fourteen years ago, of emphysema from smoking and he ate a lot of hydrolized fat.” she admitted to me, her dark eyes shining with emotion,“When he died, I threw away the biscuits and I bought a book on nutrition and studied it, and now I’ve got strong. I only eat wholemeal bread, white bread’s a killer. I am keeping well, to stay alive for the sake of my children because I love them. I don’t want to go the same way my husband did.”

“Anna Pellicci makes me laugh, ‘She says, ‘Are you still here?”” continued Henrietta with affectionate irony, leaning closer and casting her eyes around the magnificent panelled cafe that is her second home,“I first came to Pelliccis in 1947 when I got married. No-one had washing machines then, so I used to take my washing to the laundrette and come here with my three babies, Lesley hanging onto the pram, Linda sitting on the front and Lorraine the baby inside.” Yet in spite of being around longer than anyone else, Henrietta possesses a youthful, almost childlike, energy and wears a jaunty bow in her hair. “I’m so tiny,” she declared to me batting her eyelids flirtatiously, “I’m just a little girl.”

As a prelude the afternoon’s performance, I asked Henrietta the origin of her singing and she grew playful, speaking with evident delight and invoking emotions from long ago. “It all started with my dad when I was a little girl, he had a beautiful voice.” she recalled fondly, “He was a road sweeper, but years ago there wasn’t much work – so, when he couldn’t get a job, he used to stand outside the pub singing. And people put money in his hat, and he took it home and gave to my mum. That was the only entertainment we had in those days. Everybody was poor, so the best thing was to go to the pub and make your own music. When I was sixteen years old, I used to sing duets with my dad in pubs. The first song I sang was “Sweet Sixteen – When I first saw the love light in your eyes, when you were sweet sixteen…”

Henrietta got lost in the sentiment, singing the opening line of Sweet Sixteen across the table in a whisper, before the choosing the moment to assure me,“I’m a ballad singer, I don’t like to sing ‘Hey, Big Spender!’ even though I think Shirley Bassey’s marvellous – that suits her voice, not mine.” I nodded sagely in acknowledgement of the distinction, before she continued with a fresh thought, “But I like Country & Western. Have you heard of Patsy Cline and Lena Martell? I like that one, ‘I go to pieces each time I see you again…'”

Born in the old Bethnal Green Hospital in the Cambridge Heath Rd, Henrietta and all her family – even her great-grandparents – lived in Shetland St opposite. Evacuated at the age of ten to Little Saxham, near Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk, Henrietta found herself with a devout Welsh family who worked on the land and went to church on Sundays. Here Henrietta excelled in the choir and “that’s how I learnt singing. I got to sing, ‘My Lord is Sweet,’ on my own and I loved it.” she confided to me with a tender smile.

Returning to the East End at the time of the doodlebugs, Henrietta was out playing with her friend Doris when they heard the sound of the Luftwaffe overhead followed by explosions. In the horror of the moment, Doris suggested they take refuge in Bethnal Green Tube Station, but Henrietta had the presence of mind to refuse and went instead to join her family sleeping under the railway arches. That night, one hundred and seventy three people were killed on the staircase as they crowded into the entrance of the tube, including Henrietta’s friend Doris. “It’s not for your eyes,” Henrietta’s father told her when they laid out the bodies on stretchers upon the pavements in lines, but she recalls it in vivid detail to this day.

We ate in silence for a while before Henrietta resumed her story.“When my children started school, I joined the Diamond “T” Concert Party,” she told me,”I had a friend who worked at Tate & Lyle in Silvertown and one of the things they did for the community was organise entertainments. We used to go to old people’s homes, churches and hospitals, and I became one of their singers for thirty years. We had quite a laugh. The only reason I left was that everyone else died.”

I understood something of Henrietta’s circumstance, her story, the origin of her singing and how she made use of her talent over all these years. I realised it was imperative that Henrietta continues singing, if she is to seek the longevity she desires, and for one born and bred in Bethnal Green, Pelliccis is the natural venue. Yet there was one mystery left – why does everyone know Henrietta as ‘Joan’ ?

“My mum was called Henrietta, and because I was the eldest I was called Henrietta, but I hated it so I when I went for my first job interview, as a machinist in Mare St making army denims, I told them I was called, “Joan.” she confessed, “They was more cockney there than I am, they said, ‘What’s your name, love?’ and I didn’t like calling out ‘Henrietta’ because it sounded so posh, I just said the first name that came into my head – ‘Joan.’ All my neighbours and my mother-in-law know me as Joan, but my family know me as Henrietta. And that’s how I told a little white lie, in case you might be wondering.”

As our conversation passed, we had completed our meals. Joan ordered a piece of bread pudding to take home to eat later and I polished off a syrup pudding with custard. And then, the moment arrived – Henrietta took her microphone from her bag and composed herself to sumon the spirit of the place, a hush fell upon the cafe and she sang…

“I’m a ballad singer, I don’t like to sing ‘Hey, Big Spender!”

Henrietta Keeper – “I’m so tiny, I’m just a little girl.”

You may like to read my other Pelliccis stories

A Visit To Great Tom At St Paul’s

In the second of my series of the stories of Whitechapel Bells, I visit one of London’s biggest bells

Click to hear the sound of Great Tom

Like bats, bells lead secluded lives hibernating in dark towers high above cathedrals and churches. Thus it was that I set out to climb to the top of the south west tower of St Paul’s Cathedral last week to visit Great Tom, cast by Richard Phelps at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in 1716.

At 11,474lbs, Great Tom is significantly smaller than Great Paul, its neighbour in the tower at 37,483lbs, yet Great Paul has been silent for many years making Great Tom the largest working bell at St Paul’s and, if Big Ben (30,339lbs) falls silent during renovations this year, then Great Tom will become London’s largest working bell.

To reach Great Tom, I had first to climb the stone staircase beneath the dome of St Paul’s and then walk along inside the roof of the nave. Here, vast brick hemispheres protrude as the reverse of the shallow domes below, creating a strange effect – like a floor of a multi-storey car park for flying saucers. At the west end, a narrow door leads onto the parapet above the front of the cathedral and you descend from the roof of the nave to arrive at the entrance to the south west tower, where a conveniently placed shed serves as a store for spare clock hands.

Inside the stone tower is a hefty wooden structure that supports the clock and the bells above. Here I climbed a metal staircase to take a peek at Great Paul, a sleek grey beast deep in slumber since the mechanism broke years ago. From here, another stone staircase ascends to the open rotunda where expansive views across the city induce stomach-churning awe. I stepped onto a metal bridge within the tower, spying Great Paul below, and raised my eyes to discern the dark outline of Great Tom above me. It was a curious perspective peering up into the darkness of the interior of the ancient bell, since it was also a gaze into time.

When an old bell is recast, any inscriptions are copied onto the new one and an ancient bell like Great Tom may carry a collection of texts which reveal an elaborate history extending back through many centuries. The story of Great Tom begins in Westminster where, from the thirteenth century in the time of Henry III, the large bell in the clocktower of Westminster Palace was known as ‘Great Tom’ or ‘Westminster Tom.’

Great Tom bears an inscription that reads, ‘Tercius aptavit me rex Edwardque vocavit Sancti decore Edwardi signantur ut horae,’ which translates as ‘King Edward III made and named me so that by the grace of St Edward the hours may be marked.’ This inscription is confirmed by John Stowe writing in 1598, ‘He (Edward III) also built to the use of this chapel (though out of the palace court), some distance west, in the little Sanctuary, a strong clochard of stone and timber, covered with lead, and placed therein three great bells, since usually rung at coronations, triumphs, funerals of princes and their obits.’

With the arrival of mechanical clocks, the bell tower in Westminster became redundant and, when it was pulled down in 1698, Great Tom was sold to St Paul’s Cathedral for £385 17s. 6d. Unfortunately, while it was being transported the bell fell off the cart at Temple Bar and cracked. So it was cast by Philip Wightman, adding the inscription ‘MADE BY PHILIP WIGHTMAN 1708. BROUGHT FROM THE RVINES OF WESTMINSTER.’

Yet this recasting was unsatisfactory and the next year Great Tom was cast again by Richard Phelps at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. This was also unsuccessful and, seven years later, it was was cast yet again by Richard Phelps at Whitechapel, adding the inscription ‘RICHARD PHELPS MADE ME 1716’ and arriving at the fine tone we hear today.

As well as chiming the hours at St Paul’s, Great Tom is also sounded upon the death of royalty and prominent members of the clergy, tolling last for the death of the Queen Mother in 2002. For the sake of my eardrums, I timed my visit to Great Tom between the hours. Once I had climbed down again safely to the ground, I walked around the west front of the cathedral just in time to hear Great Tom strike noontide. Its deep sonorous reverberation contains echoes of all the bells that Great Tom once was, striking the hours and marking out time in London through eight centuries.

Above the nave

Looking west with St Brides in the distance

Spare clock hands

Looking east along the roof of the cathedral

Up to the clock room

The bell frame for Great Paul in the clock room

Great Paul

Looking up to Great Paul

Looking across to the north west tower from the clock room

Looking along Cannon St from the rotunda

Looking south to the river

Looking across to the north west tower

Looking down on Great Paul

Looking up into the bell frame

Looking up to catch a glimpse of Great Tom, St Paul’s largest working bell

Great Tom cast by Richard Phelps in Whitechapel in 1716, engraved in 1776 (Courtesy of The Ancient Society of College Youths)

Great Tom strikes noon at St Paul’s Cathedral

You may also like to read about

A Petition to Save the Bell Foundry

Save the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

So Long, Whitechapel Bell Foundry