The Englishman & The Eel

I am delighted to announce that Stuart Freedman’s magnificent photographic survey of the culture of pie, mash and eels, THE ENGLISHMAN & THE EEL is published by Dewi Lewis Books. Click here to order a copy

At Manze’s Tower Bridge Rd, London’s oldest Pie & Mash Shop, which opened in 1897

In days like these, we all need steaming-hot pie & mash & eels to fortify us, as we face the vicissitudes of life and the weather. It gave photographer Stuart Freedman the excuse to visit some favourite culinary destinations and serve up these tasty pictures for us, accompanied by this brief historical introduction as an appetiser.

“Eels have long been a staple part of London food and were once synonymous with the city and its people. Lear’s Fool in his ramblings to the King, witters – “Cry to it, nuncle, as the Cockney did to the eels when she put ‘em i’ the paste alive, she knapped ‘em o’ the coxcombs with a stick, and cried ‘Down, wantons, down!’”

In a city bisected by the Thames, the eel’s popularity was that it was plentiful, cheap and, when most meat or fish had to be preserved in salt, eels could be kept alive in puddles of water. Reverend David Badham reports in his ‘Prose Halieutics Or Ancient & Modern Fish Tattle’ in 1854 – “London steams and teems with eels alive and stewed. For one halfpenny, a man of the million may fill his stomach with six or seven long pieces and wash them down with a sip of the glutinous liquid they are stewed in.”

Such was the demand that eels were brought over from The Netherlands in great quantities by Dutch eel schuyts, commended for helping feed London during the Great Fire. Although they were seen as inferior to domestic eels, the British government rewarded the Dutch for their charity by Act of Parliament in 1699, granting them exclusive rights to sell eels from their barges on the Thames.

When the Thames became increasingly polluted and could no longer sustain a significant eel population during the nineteenth century, the Dutch ships had to stop further upstream to prevent their cargo being spoiled and the rise of the Pie & Mash Shops was a direct result of the adulteration of eels and pies sold on the streets.”

A delivery of live eels at F. Cooke in Hoxton

Joe Cooke kills and guts the eels freshly at the rear of his shop in Hoxton Market

A dish of jellied eels served up in Hoxton

Paddy makes the pie lids at F. Cooke in Broadway Market

Tasty pies awaiting their destiny in Broadway Market

Joe strains the golden potatoes in Hoxton

Joe fills a bucket of creamy mash behind the counter in Hoxton

Kelly dishes up pies & mash with liquor at Manze’s in Tower Bridge Rd

Tucking in at Manze’s in Tower Bridge Rd

Manze’s, Walthamstow

Manze’s, Tower Bridge Rd

Sawdust at Manze’s in Walthamstow

Victorian tiling at Manze’s in Tower Bridge Rd

Original 1897 interior at Manze’s in Tower Bridge Rd

Lisa at Manze’s in Walthamstow

Miss Emily McKay enjoying pie & mash as an eighty-eighth birthday treat in Broadway Market

Clock of 1911 at F. Cooke in Broadway Market

Interior of F. Cooke in Broadway Market

F.Cooke – “trading from this premises since 1900”

Enjoying eels in Hoxton Market

Interior of Manze’s in Walthamstow

Art Nouveau tiles in Walthamstow

Vinegar, salt & pepper on marble tables at F.Cooke in Hoxton Market

Wolfing it down at Manze’s in Tower Bridge Rd

Glass teacups at Manze’s in Walthamstow

Wooden benches and tables of marble and wrought iron at Manze’s in Tower Bridge Rd

Bob Cooke, fourth generation piemaker, at F.Cooke in Broadway Market

Photographs copyright © Stuart Freedman

You may also like to read about

Boiling the Eels at Barney’s Seafood

Some Favourite Pie & Mash Shops

So Long, Milly Rich

I only learnt the sad news this week that Milly Rich died last year on 6th October at the grand age of one hundred. As her daughter Shula said to me, ‘her heart could not keep up with her any longer.’ I feel privileged to have met Milly and I publish my interview with her today as a tribute.

“You know, being nearly a hundred is a lot of years to account for…”

Portrait of Milly Rich by Patricia Niven

The Gentle Author – Are you from the East End?

Milly Rich – I am from the last place I have lived! But I was born at 19 Commercial Rd on October 23rd 1917, which of course was during the First World War and my mother, Leah, told me that the air raid warnings were sounding at the time. People were terrified of air raids but my she had a basement under her shop in Commercial Rd where she took shelter.

My mother made corsets and she taught me to make them too. Corsets were a vital part of a lady’s outfit in those days because – of course – smart clothes needed a good foundation and a good foundation was a nice heavily-boned corset with a strong steel bust in the front. Everybody had remarkably good posture, not slumped – like you see today – over a hand-held computer.

The Gentle Author – Your mother was proprietor of the shop?

Milly Rich – I have a picture of her standing outside the shop with her two assistants when she was not yet twenty. She was very creative, very artistic – and she got her first job in an embroidery factory in Hanbury St. Then she opened a shop at 87 Brick Lane and – many years later – it transpired that the young man I married was the son of the owner of the embroidery factory where my mother had once been a designer. So the world is full of concentric circles!

The Gentle Author – Tell me about your father.

Milly Rich – My father, Morris Levrant, was an ‘émigré of the Empire of Russia’ and I know that because he went to America first and patented an airtight valve for bicycle tyres when he was thirty. He was very clever. My mother said he spoke nine languages and he was an inventor. He was born in Siedlce in Poland where my daughter has traced our family back to 1733.

He left a wife and three children in New York when he came to London and my mother’s father was not very happy about that. Apparently, my grandfather put him through hoops to prove that he was properly divorced. I do not know how he got the divorce but he obviously did because otherwise they would not have allowed the marriage. My parents were married in Princelet St Synagogue and I was born in 1917, so I suppose they were married in 1916.

The Gentle Author – Do you have brothers and sisters?

Milly Rich – I had one brother, Mossy. He is dead now, he died at seventy-five years old. I suppose it speaks volumes for the kind of life we led that he had rickets, which is caused by malnutrition. He was very good with his hands and became a jeweller and worked in Black Lion Yard and Hatton Garden.

When the Jews were promised a homeland in the Balfour Declaration, my father decided he would settle in what was then Palestine. Of course, he was an inventor, and he was agog to go and be an inventor there – he was a clever chap. So in 1921 we set sail.

The Gentle Author – You shut the shop in Commercial Rd?

Milly Rich – Yes, we got rid of it and went off to Palestine but a war broke out there and, in the first month, my father was killed and he was buried there. He was only forty when he died and left three children in New York. We found them not very long ago. The two sisters were still alive, they were ten and eleven years older than me. We went and stayed with them, and they were lovely. They turned out to be artists and designers too

When my father died, my mother was expecting my brother, so she could not come back from Palestine at once but she did not speak the language and, of course, my father had all the money – she was stuck in Jaffa. Fortunately my uncle – my mother’s sister’s husband – came to the rescue and got us back to England. By that time, I was three, I remember. And we were stuck in Boulogne because I had a watery eye – they thought it was catching – an eye disease, maybe trachoma but it was just a trapped eyelash.

On our return, we stayed with my uncle in Whitechapel. He had a jewellery shop opposite the Whitechapel Gallery, it was museum as well in those days. I remember they had a septic mouse in a case on the stairs and an illuminated panorama of Medieval London on the landing. It was lovely, I used to stand and stare at it for hours.

We stayed there until my uncle found the shop at 192 Bethnal Green Rd. It was flanked on one side by the Liberal Party headquarters, Sir Percy Harris was the MP, and on the other side by a newsagent. They were not Jewish, but everybody was on excellent terms and there was no anti-Semitism where we were.

We lived above the shop and we had tenants as well, who had to come through the shop. Originally, it been a house and garden but it had been transformed into one great long space. My mother had a curtain put up to screen people walking through because they had to cross our parlour, which my mother also used as a fitting room for the corsets.

Women used to come in and treat her as an agony aunt. Like a hairdresser or a dressmaker, she was a recipient of confidences. All the locals would tell my mother their troubles which invariably were to do with their husbands. They used to speak Yiddish so that I should not hear but, knowing they were speaking so I could not understand, I soon picked up Yiddish. I never let on that I could and, of course, I would tell the stories to my friends at school which was a source of much merriment.

There was a window in the parlour so my mother could see if anyone came into the shop. My brother used to climb up to look through it at the women trying on the corsets and, of course, a good time was had by all!

The Gentle Author – What took you out of Bethnal Green?

Milly Rich – I won a scholarship to Central Foundation School in Spital Sq. It was a fee-paying school at the time and there used to be quite a division between the scholarship girls and the fee-paying pupils. I was a great reader and I have always loved words and I had a good vocabulary. The other children did not like it. “Oh you’ve swallowed a dictionary,” that was a great insult. I did not care, did I? From there, I won another scholarship but I could not make up my mind whether to go to the London School of Economics, because I wanted to be a journalist, or St Martin’s School of Art.

In the event, I decided I would not train to be a journalist because I was not going to learn shorthand – I was not going to take down anybody else’s words. So I took the place at St Martin’s instead and hated it. We used to sign in and go off to the local Lyons teashop and sit there for hours, making patterns on the tablecloth with the salt cellar. Eventually, my mother could not afford for me to stay there any longer because I only got ten shillings a week and I did not like it anyway – I do not like any form of regimentation.

I got a job inscribing certificates because I was quite good at lettering and I did that for a couple of months. It was trees in Israel. They kept planting forests and I used to write ‘five trees planted in the name of so-and-so on the occasion of his this-and-that.’

I did not do it for long, I got a job in a drawing office instead. I told them I could do it, even though I had never held a drawing pen in my life. They said, “Well, here’s one – take it home and bring it back tomorrow, completed.” I went into an art shop and asked, “How do you do this?” They showed me a drawing pen and how you filled it and how you used it, so I went home and I did the drawing and I took it back the next day and I got the job. The drawing office was quite fun actually, I enjoyed it there. It was right at the top of Crown House, which is still there on the corner of Drury Lane and Aldwych. We used to feed the pigeons and there was a Sainsbury’s around the corner which delivered lunch in a box. You got a sandwich and some orange juice and a piece of cake for sixpence.

You know – being nearly a hundred is a lot of years to account for.

The Gentle Author – Tell me about Moss, your husband.

Milly Rich – We met at a play-reading group. He was a writer, and I always liked plays and acting and so on. We met there and he would walk me home.

The Gentle Author – Where did he come from?

Milly Rich – His father had the embroidery factory in Hanbury St, where my mother had once worked doing the patterns although we did not realise that at the time. It was only when our parents were introduced that they realised that they all knew each other already. Small world. People were so ready to help each other, I do not know if people are still like that in the East End, but they were once. I remember the blackshirts marching down Bethnal Green Rd and shouting “The Jews, the Jews, we’ve got to get rid of the Jews!” Whenever they passed our shop, my brother used to be outside yelling.

The Gentle Author – Did you feel threatened?

Milly Rich – I do not think I was aware of it, but I became aware because Moss used to take me to the political meetings and the Unity Theatre. When there was the Battle of Cable St, we went there. I remember leaning on the lamppost outside Gardiner’s Corner and we were all yelling, “They shall not pass, they shall not pass.”

The Gentle Author – That was eighty years ago.

Milly Rich – Then war was declared and we all thought the first air raid would obliterate London. Everybody was terrified and I had known Moss four years, so he said “We’d better get married right away, while we can,” and he got a special licence. I did not want any fuss and I told my mother, “I’m not having any ‘do’” because getting married, especially in Jewish families, was a great occasion you know. I said, “I’m not having any family there.” It was the custom then – I do not know what people do now– for the woman to take the man’s name but I did not like that, so I said, “If I have got to take your name, you have got to take my name.” His name was Rich and my name was Levrant so we became Levrant Rich, which sounds quite good.

The Gentle Author– Was that unusual in those days?

Milly Rich – Goodness knows! Moss was very easy about it, he said he did not care. My mother said she would kill herself if we did not get married in the synagogue, but I said “I’m not having anyone there , I don’t want a fuss,” so she agreed she would not tell anyone. But when Moss and I arrived at the synagogue, standing outside wreathed in smiles was my fat Aunty Milly and her husband. I said, “I’m not going to do it!” and we turned tail and ran away, so we did not get married that day.

We came back the next day and got married when nobody was there. We got no photographs, nothing. It was just the two of us, and Moss had to go back to work because he was in the timber importing business, doing the advertising, and everybody thought the work was absolutely vital. So he went back to work and I went shopping in Petticoat Lane for a couple of cups and saucers and a saucepan.

Moss had found us an attic room at 4 Mecklenburgh Sq and we went back there. It was one pound a week which was a lot of money for rent. There was an oven on the landing which four other tenants used and we each took a turn to put a shilling in the meter. Sometimes, I would come back early and find the landlady on her knees fiddling the meter!

When the air raid siren went, we dashed down to the shelter which was just opposite. One night we got a direct hit. The thing shuddered but it did not go off and we were marshalled out by wardens. I remember walking up Gray’s Inn Rd with fires blazing on either side right up to Euston Station. There were aeroplanes droning overhead and the church opposite the station was on fire. We were ushered into the station and we spent the rest of the night there, before returning to Mecklenburgh Sq.

Although our rent was one pound a week, Moss earned four pounds and I earned two pounds and a bit, so we only had just over six pounds as our total income. After our pound rent was paid and Moss had ten cigarettes delivered each day, I used to be able to send stuff to the laundry. They would come and collect and deliver it, all freshly ironed, and a sheet was tuppence to launder. Can you imagine? Shirts and everything. I never did any washing myself. As well as Mrs Pointy the landlady, there was a caretaker who kept our two rooms clean for two shillings a week, which was very nice. Mrs Pointy used to feed her cat cods’ heads and the smell – I can still smell it – was absolutely indescribable.

The Gentle Author – Nowadays in London, many people spend half their wages on rent.

Milly Rich – I was just thinking about the nature of progress. When I was young, it was usual for a woman to stay at home and the man would bring home the money – his wage could support the wife and the family. Now two wages are not enough, do you call that progress?

Transcript by Rachel Blaylock

Milly, aged one and a half in 1919

Milly, aged five in 1922

Milly, aged twenty in 1939

Moss in 1939

Milly & Moss’ Marriage Certificate, 1939

Milly’s London Transport card, 1939

Milly & Moss in the forties

Milly & Moss in the eighties – Milly & Moss were married for seventy-two years

You may also like to read about

Maurice Sills, St Paul’s Cathedral Treasure

Jack Corbett, London Oldest Fireman

Aaron Biber, London’s Oldest Barber

Charlie Burns, Waste Paper Dealer

Looking Down On Old London

In my dream, I am flying over old London and the clouds part like curtains to reveal a vision of the dirty monochrome city lying far beneath, swathed eternally in mist and deep shadow.

Although most Londoners are familiar with this view today, as the first glimpse of home on the descent to Heathrow upon their return flight from overseas, it never ceases to induce wonder. So I can only imagine the awe of those who were first shown these glass slides of aerial views from the collection of the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society at the Bishopsgate Institute a century ago.

Even before Aerofilms was established in 1919 to document the country from above systematically, people were photographing London from hot air balloons, zeppelins and early aeroplanes. Upon first impression, the intricate detail and order of the city is breathtaking and I think we may assume that a certain patriotic pride was encouraged by these views of national landmarks which symbolised the political power of the nation.

But there is also a certain ambivalence to some images, such as those of Horseguards’ Parade and Covent Garden Market, since – as much as they record the vast numbers of people that participated in these elaborate human endeavours, they also reduce the hordes to mere ants and remove the authoritative scale of the architecture. Seen from above, the works of man are of far less consequence than they appear from below. Yet this does not lessen my fascination with these pictures, as evocations of the teeming life of this London that is so familiar and mysterious in equal measure.

Tower of London & Tower Bridge

Trafalgar Sq, St Martin-in-the-Fields and Charing Cross Station

Trafalgar Sq & Whitehall

House of Parliament & Westminster Bridge

Westminster Bridge & County Hall

Tower of London & St Katharine Docks

Bank of England & Royal Exchange

Spires of City churches dominate the City of London

Crossroads at the heart of the City of London

Guildhall to the right, General Post Office to the left and Cheapside running across the picture

Blackfriars Bridge & St Paul’s

Hyde Park Corner

Buckingham Palace & the Mall

The British Museum

St James’ Palace & the Mall

Ludgate Hill & St Paul’s

Pool of London & Tower Bridge with Docks beyond

Albert Hall & Natural History Museum

Natural History Museum & Victoria & Albert Museum

Limehouse with St Anne’s in the centre & Narrow St to the right

Reversed image of Hungerford Bridge & Waterloo Bridge

Covent Garden Market & the Floral Hall

Admiralty Arch

Trooping the Colour at Horseguards Parade

St Clement Dane’s, Strand

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Glass slides courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Lantern Slides of Old London

The High Days & Holidays of Old London

The Fogs & Smogs of Old London

The Forgotten Corners of Old London

The Statues & Effigies of Old London

The Reckoning With Crest Nicholson

David & Goliath by Osmar Schindler c.1888

Two weeks ago, I wrote to Crest Nicholson regarding their use without permission of my photograph of the Bethnal Green Mulberry in their leaflets and exhibition for their proposed London Chest Hospital Development. Although I would never have granted them permission, I asked them to pay for the use that had occurred. And yesterday they did so.

Last week – in an appalling moment of moral exposure – their response was to attempt to gag my criticism of their development and their plan to dig up the ancient Mulberry tree, as a condition of payment. Yet I reminded them I was under no obligation to accept any conditions from them, whereas they were legally obligated to pay me for their use of my photograph which was in clear breach of the law of copyright.

This week, thanks in no small measure to the magnificent support I received from you, the readers of Spitalfields Life, Crest Nicholson realised that they had no option but the pay me without requesting any conditions. Now they have admitted liability, I can consider whether to pursue action for damages.

In the meantime, there is a still time to write a letter of objection to their rotten London Chest Hospital development which includes digging up the Bethnal Green Mulberry. You will find a helpful guide below that explains how to write an objection which carries legal weight.

Read the pitiful saga here

Design by Paul Bommer

This is a simple guide to how to object effectively to Crest Nicholson’s application to redevelop the former London Chest Hospital in Bethnal Green.

Tower Hamlets Council will accept emails and letters until the Hearing of the Application, which is likely to be in March. Please send comments as soon as possible to be sure they are included in the planning officer’s report.

It is important to use your own words and add your own personal reasons for opposing this development. Any letters which simply duplicate the same wording will count only as one objection.

Be sure to state clearly that you are objecting to the application.

If you do not include your postal address your objection will be discounted.

Points in bold are material considerations and are valid legal reasons for Councils to refuse Applications.

Take a look at the full Application by following this link

Planning application PA/16/03342/A1

1. SOCIAL HOUSING

The level of social housing is below 28%, too far beneath the Mayor’s target of 50%.

2. THE LISTED BUILDING

The application proposes to demolish the Grade II listed 1860s south wing, causing harm to the designated heritage asset, and would therefore fail to comply with Paragraph 66 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990; National Planning Policy Framework paragraphs: 126, 131, 132, 133 and 134; as well as Tower Hamlets Local Plan Policy SP12.

The proposal would see the roof structure of the listed buildings unnecessarily rebuilt with new materials, involving the loss of original historic fabric when the applicant’s own survey notes that the chimneys are in ‘good condition’, and that the roof is ‘in a sound condition’. As such National Planning Policy Framework paragraphs: 126, 131, 132, 133 and 134 should be applied.

3. THE VICTORIA PARK CONSERVATION AREA

The development will damage the Victoria Park Conservation Area. The conservation area appraisal notes that: ‘Landmark institutional buildings generally sit within their own landscaped gardens, in keeping with the open character and setting of Victoria Park. The London Chest Hospital, opened in 1855, is the most significant of these buildings, in terms of its presence in the urban environment’.

The construction of large blocks beside the London Chest Hospital will deprive a landmark listed building of its open landscaped space and destroy the character of the conservation area. Paragraph 72 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990, and National Planning Policy Framework paragraphs 137 and 138 should therefore be applied when considering this application.

4. THE MULBERRY TREE

Deep concerns exist over the proposed digging up of the ancient Mulberry Tree and the unlikelihood of its survival if it is moved. No credible evidence has been put forward that this tree, which is subject to a Tree Protection Order, is not a veteran tree.

Paragraph 118 of National Planning Policy Framework 2012 states that ‘planning permission should be refused for development resulting in the loss of … aged or veteran trees found outside ancient woodland, unless the need for, and benefits of, the development in that location clearly outweigh the loss’

Paragraph 197 of The Town and Country Planning Act 1990 states that local planning authorities, ‘must ensure, whenever it is appropriate, that in granting planning permission for any development adequate provision is made, by the imposition of conditions, for the preservation or planting of trees’.

WHERE TO SEND YOUR OBJECTION

Letters and emails should be addressed to

planningandbuilding@towerhamlets.gov.uk

Quote application: PA/16/03342/A1

Town Planning, Town Hall, Mulberry Place, 5 Clove Crescent, London, E14 2BG

Crest Nicholson’s proposed redevelopment of London Chest Hospital

You may also like to read about

Here We Go Round The Bethnal Green Mulberry

A Plea For The Bethnal Green Mulberry

Eva Frankfurther, Artist

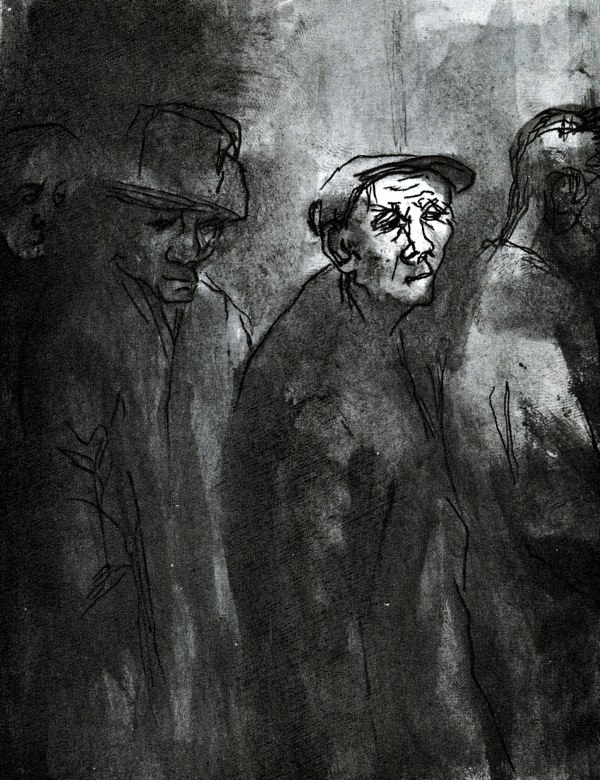

There is an unmistakeable melancholic beauty which characterises Eva Frankfurther‘s East End drawings made during her brief working career in the nineteen-fifties. Born into a cultured Jewish family in Berlin in 1930, she escaped to London with her parents in 1939 and studied at St Martin’s School of Art between 1946 and 1952, where she was a contemporary of Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach.

Yet Eva turned her back on the art school scene and moved to Whitechapel, taking menial jobs at Lyons Corner House and then at a sugar refinery, immersing herself in the community she found there. Taking inspiration from Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz and Picasso, Eva set out to portray the lives of working people with compassion and dignity.

In 1959, afflicted with depression, Eva took her own life aged just twenty-eight, but despite the brevity of her career she revealed a significant talent and a perceptive eye for the soulful quality of her fellow East Enders.

“West Indian, Irish, Cypriot and Pakistani immigrants, English whom the Welfare State had passed by, these were the people amongst whom I lived and made some of my best friends. My colleagues and teachers were painters concerned with form and colour, while to me these were only means to an end, the understanding of and commenting on people.” – Eva Frankfurther

Images copyrigh t© Estate of Eva Frankfurter

You may also wish to take a look at

A Reply From Crest Nicholson

Ten days ago, I wrote to Crest Nicholson regarding their use without permission of my photograph of the Bethnal Green Mulberry in their leaflets and exhibition for their proposed London Chest Hospital Development. I was encouraged by their initial response, admitting ‘we made a mistake’ and apologising ‘I am sorry you have had to contact us in this respect.’ But then this disappointing letter arrived from the Company Secretary which attempts to gag my criticism of their development and their plan to dig up the ancient Mulberry tree. Click here to read my initial letter.

(Click on this letter to enlarge)

My reply emailed to Crest Nicholson today:

29th January 2018

Dear Kevin Maguire,

Thankyou for your letter of 25th January in response to my letter of 17th January, relating to your use without permission of my photograph of the Bethnal Green Mulberry, which you reproduced in your leaflets and exhibition for your proposed London Chest Hospital development.

I understand that you have ceased circulation of the leaflet, removed my photograph from your exhibition and are now offering to pay for this usage.

However, I am unable to agree with your proposed letter of agreement in its current form.

I see no need for confidentiality in this matter and intend to continue to publish our correspondence as I have done to date. The confidentiality provision should be removed.

The statement referring to no admission of liability is a nonsense – you have acknowledged that it is my photograph which you have used without my permission. There is a clear breach of my copyright for which there is liability.

Your language concerning what I may or may not publish in the future is totally irrelevant to the issue of your breach of my copyright and has no place in the letter.

“by accepting this payment you agree that you shall not publish or cause to be published any false, misleading, derogatory, or disparaging comments about Crest Nicholson.”

You well know that I am critical of your proposed London Chest Hospital development and your attempts to secure permission to dig up the ancient Bethnal Green Mulberry, so I am unwilling to sign a document which would grant you recourse to take action against me if I were to write anything that you might choose to interpret as “false, misleading, derogatory, or disparaging.”

You underestimate me if you think that I will permit you to gag me by making it a condition of payment.

May I remind you it was your indefensible behaviour in using my photograph without permission in your leaflet discrediting the history of the Bethnal Green Mulberry which was the catalyst for this dialogue?

I am under no obligation whatsoever to accept any conditions of payment from you, but you are under legal obligation to pay me for the use of my photograph which was in clear breach of the law of copyright.

Please pay me without further delay.

Yours sincerely

The Gentle Author

The Gentle Author’s photograph of the Bethnal Green Mulberry which Crest Nicholson want to dig up

The Gentle Author’s photograph as reproduced without permission by Crest Nicholson in their leaflet and exhibition for their proposed London Chest Hospital development

You may also like to read about

Here We Go Round The Bethnal Green Mulberry

A Plea For The Bethnal Green Mulberry

Beattie Orwell, Centenarian

Portrait of Beattie Orwell by Phil Maxwell

On an especially cold day recently, it was my delight to accompany Contributing Photographer Phil Maxwell to visit centenarian Beattie Orwell and sit beside her in her cosy flat while she talked to me of her century of existence in this particular corner of the East End.

A magnanimous woman who delights in the modest joys of life, Beattie is nevertheless a political animal who is proud to be one of the last living veterans of the Battle of Cable St – a formative experience that inspired her with a fiercely egalitarian sense of justice and led to her becoming a councillor in later life, acutely conscious of the rights of the most vulnerable in society.

In spite of her physical frailty at one hundred years old, Beattie’s moral courage grants her an astonishing monumental presence as a human being. To speak with Beattie is to encounter another, kinder world.

“I am Jewish and both my parents were East Enders, born here. My father’s parents came over from Russia. On my mother’s side, her parents were born here but her grandfather was born in Holland. So I am a bit of a mixture!

My father Israel worked as a porter at the Spitalfields Market and my mother Julia was a cigar maker at Godfrey & Phillips in Commercial St. I grew up in Brunswick Buildings in Goulston St, until I got bombed out. It was horrible, we had a little scullery, too small to swing a cat. My mother had one bedroom and, the three children, we slept in a put-you-up. I had two sisters Rebecca & Esther. Rebecca was the eldest, she very clever at dressmaking. When she was fifteen, she could make a dress. We needed her because my father died when he was forty-four, he had three strokes and died in Vallance Rd Hospital. I was only thirteen. He used to take me everywhere, he was marvellous. He took to me to the West End to visit my aunt, she was an old lady with a parrot and lived on Bewick St. We used to have a laugh with the parrot.

We moved to City Corporation flats in Stoney Lane and I went to Gravel Lane School. It was lovely school, they taught us housewifery. We had a little flat in the school and we used to clean it out, then go shopping in Petticoat Lane to buy ingredients to make a dinner, imagining we were married. The boys used to do woodwork and learnt to make stools and things like that. I loved that school. When I was twelve it closed and I went to the Jewish Free School in Bell Lane. It was very strict and religious. When the teacher wanted us to be quiet, she’d say, ‘I’m waiting!’ It was good, I enjoyed my school life.

I left when I was fourteen and I went to work right away, dressmaking in Alie St. I used to lay out material. I do not know why but I must have heavy fingers, I could not manage the silk. It used to fall out of my hands. I only lasted a week before I left, I could not stand it. Then I went to work with my sister at Lottereys in Whitechapel opposite the Rivoli Picture Palace, they used to make uniforms for solders. I went into tailoring, men’s trousers, putting the buttons on with a machine. We worked long hours and it was hard work. By the time I got married I was earning two pounds and ten shillings a week. I never earned big money. I worked all the way through the war. I gave all the money to my mother and she gave me a shilling back. I used to walk up to the West End. It was threepence on the trolley bus.

I was nineteen in 1936. I was there with all the crowds at the Battle of Cable St. I am Jewish and I knew we must fight the fascists. They were anti-semitic, so I felt I had to do it. I was not frightened because there were so many people there. If I was on my own I might have been frightened, but I never saw so many people. You could not imagine. Dockers, Scottish and Irish people were there. It was a marvellous atmosphere. I was standing on the corner of Leman St outside a shop called ‘Critts’ and everyone was shouting ‘ They shall not pass!’ I was with my friend and we stood there a long time, hours. So from there we walked down to Cable St where we saw the lorry turned over. I never saw the big fighting that happened in Aldgate because I was not down there, but I saw them fighting in Cable St near this turned over lorry. From there, we walked down to Royal Mint St, where the blackshirts were. They were standing in a line waiting for Oswald Mosley to come. So I said to my friend, ‘We’d better get away from here.’

We went back through Cable St to the place where we started. From there, the news came through ‘They’re not passing.’ We all marched past the place where Fascists had their headquarters – they threw flour over us, shouting – to Victoria Park where we had a big meeting with thousands of people. I had never seen anything like it in my life and I used to go to all the meetings. I never went dancing. My mother used to say, ‘I don’t know where I got you from!’ because I was only interested in politics. I am the only one like this in the whole family. I still know everything that is going on.

I used to go to Communist Party socials in Swedenborg Sq, off Cable St, and – being young – I used to enjoy it. Then I joined the Labour Party, the Labour League of Youth it was called. We used to go on rambles. It was lovely. We went to Southend once. I always used to march to Hyde Park on May Day and carry one of the ropes of our banner. I met my husband John in Victoria Park when I was with the Young Communists League, although I was not a member. They had a Sports Day and my husband was running for St Mary Atte Bowe because he was a Catholic. I met him and we went to a Labour Party dance. We got married in 1939.

We managed to get a flat in the same building as my mother, at the top of the stairs. They were private flats and I remember standing outside with a banner saying, ‘Don’t pay no rent!’ because the owners would not do the flats up. They did not look after us, it was horrible thing for us to have to do but it worked. I laugh now when I think about it. I was always brave. I am brave now.

We got bombed out of those flats while my husband was in the army. I had a baby so they sent me to Oxford where my husband was based with the York & Lancasters. We had a six-roomed house for a pound a week. My mother and sister came with me and they looked after my baby while I went to work in munitions. I was a postwoman too and I used to get up at four in the morning and walk over Magdalen Bridge.

I came back to the East End to try to get a flat here and I got caught in one of the air raids, but I knew this was where I had to live. My mother used to get under the stairs in Wentworth St when there was a raid and put a baby’s pot on her head. The war was terrible.

They sent my husband to Ikley Moor and it was too cold for him, so we came back for good. I managed to get two horrible little side rooms in Stoney Lane, sharing a kitchen between four and a toilet between two. I had no fridge, just a wooden box with chicken wire on the front. I used to go the Lane and buy two-pennorth of ice and put the butter in there. I had to buy food fresh everyday. There was a black market trade in fruit. These flats had been built for the police but the police would not have them, so they let them out to other people. All the flats were named after royalty, we were in Queens Buildings. I watched them building new flats in Cambridge Heath Rd but, before I could get one of them, I was offered a lot of horrible flats. Yet when I got there we were overcrowded, until we got a three bedroom flat at last, because I had two girls and a boy. I lived sixty-seven years there.

My husband never earned much money so I had to carry on working. He had twenty-two shillings a week pension from the army. He did all kinds of things and then got a job in the Orient Tea Warehouse. In 1966, when he was going to be Mayor of Bethnal Green and they would not give him time off, he went up to the Hackney Town Hall and got a job in the Town Clerk’s Office. He was always good at writing, he had lovely hand writing.

I became a councillor and I loved it. Our council was the best council, they were best to the old people. We used to go and visit all the old people’s homes. I never told them I was coming because I used to try and catch them out. We checked the quality of food and how clean it was. I organised dinners in York Hall for all the old people and trips to Eastbourne, but it has all been done away with – they do nothing now.

I was a councillor for ten years from 1972 until 1982. I had to fight to get the seat but I always loved old people, my husband was the same. He was known as the ‘Singing Mayor’ because he used to sing in all the old people’s homes. From when I was forty-two, I used to go round old people’s homes on Friday nights and I still do it. We have dinners together, turkey, roast potatoes and sausages, with trifle for afters.”

Beattie Orwell is featured in Phil Maxwell & Hazuan Hashim’s forthcoming film PENSIONERS UNITED. Watch the trailer and you can support this inspirational endeavour by clicking here

Photographs copyright © Phil Maxwell

See more of Phil Maxwell’s work here

Phil Maxwell’s Kids on the Street

Phil Maxwell & Sandra Esqulant, Photographer & Muse

More of Phil Maxwell’s Old Ladies

Phil Maxwell’s Old Ladies in Colour