So Long, Stanley Rondeau

Stanley Rondeau died on 13th January aged ninety-two. His funeral will be on Wednesday 25th February at Edmonton Cemetery, 11.30am

Stanley Rondeau (1933-2026)

If you visited Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church, Spitalfields on any given Tuesday, you would find Stanley Rondeau – where he volunteered one day each week – welcoming visitors and handing out guide books. The architecture is of such magnificence, arresting your attention, that you might not even have noticed this quietly spoken white-haired gentleman sitting behind a small table just to the right of the entrance, who came here weekly on the train from Enfield.

But if you were interested in local history, then Stanley was one of the most remarkable people you could hope to meet, because his great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Jean Rondeau was a Huguenot immigrant who came to Spitalfields in 1685.

“When visiting a friend in Suffolk in 1980, I was introduced to the local vicar who became curious about my name and asked me ‘Are you a Huguenot?'” explained Stanley with a quizzical grin. “I didn’t even know what he meant,” he added, revealing the origin of his life-changing discovery, “So I went to Workers’ Educational Association evening classes in Genealogy and that was how it started. I’ve been at it now for thirty years. My own family history came first, but when I learnt that Jean Rondeau’s son John Rondeau was Sexton of Christ Church, I got involved in Spitalfields. And now I come every Tuesday as a volunteer and I like being here in the same building where he was. They refer to me as ‘a piece of living history’, which is what I am really. Although I have never lived here, I feel I am so much part of the area.”

Jean Rondeau was a serge weaver born in 1666 in Paris into a family that had been involved in weaving for three generations. Escaping persecution for his Protestant faith, he came to London and settled in Brick Lane, fathering twelve children. Jean had such success as weaver in London that in 1723 he built a fine house, number four Wilkes St, in the style that remains familiar to this day in Spitalfields. It is a indicator of Jean’s integration into British society that his name is to be discovered on a document of 1728 ensuring the building of Christ Church, alongside that of Edward Peck who laid the foundation stone. Peck is commemorated today by the elaborate marble monument next to the altar, where I took Stanley’s portrait which you can see above.

Jean’s son John Rondeau was a master silk weaver and in 1741 he commissioned textile designs from Anna Maria Garthwaite, the famous designer of Spitalfields silks, who lived at the corner of Princelet St adjoining Wilkes St. As a measure of John’s status, in 1745 he sent forty-seven of his employees to join the fight against Bonnie Prince Charlie. Appointed Sexton of the church in 1761 until his death in 1790, when he was buried in the crypt in a lead coffin labelled John Rondeau, Sexton of this Parish, his remains were exhumed at the end of twentieth century and transported to the Natural History Museum for study.

“Once I found that the crypt was cleared, I made an appointment at the Natural History Museum, where Dr Molleson showed his bones to me,” admitted Stanley, widening his eyes in wonder. “She told me he was eighty-five, a big fellow – a bit on the chubby side, yet with no curvature of the spine, which meant he stood upright. It was strange to be able to hold his bones, because I know so much about his history,” Stanley told me in a whisper of amazement, as we sat together, alone in the vast empty church that would have been equally familiar to John the Sexton.

In 1936, a carpenter removing a window sill from an old warehouse in Cutler St that was being refurbished was surprised when a scrap of paper fell out. When unfolded, this long strip was revealed to be a ballad in support of the weavers, demanding an Act of Parliament to prevent the cheap imports that were destroying their industry. It was written by James Rondeau, the grandson of John the Sexton who was recorded in directories as doing business in Cutler St between 1809 and 1816. Bringing us two generations closer to the present day, James Rondeau author of the ballad was Stanley’s great-great-great-grandfather. It was three generations later, in 1882, that Stanley’s grandfather left Sclater St and the East End for good, moving to Edmonton when the railway opened. And subsequently Stanley grew up without any knowledge of Huguenots or the Spitalfields connection, until that chance meeting in 1980 leading to the discovery that he was an eighth generation British Huguenot.

“When I retired, it gave me a new purpose,” said Stanley, cradling the slender pamphlet he has written entitled The Rondeaus of Spitalfields. “It’s a story that must not be forgotten because we were the originals, the first wave of immigrants that came to Spitalfields,” he declared. Turning the pages slowly, as he contemplated the sense of connection that the discovery of his ancestry has given him, he admitted, “It has made a big difference to my life, and when I walk around in Christ Church today I can imagine my ancestor John the Sexton walking about in here, and his father Jean who built the house in Wilkes St. I can see the same things he did, and when I am able to hear the great eighteenth century organ, once it is restored, I can know that my ancestor played it and heard the same sound.”

There is no such thing as an old family, just those whose histories are recorded. We all have ancestors – although few of us know who they were, or have undertaken the years of research Stanley Rondeau had done, bringing him into such vivid relationship with his ancestors. It granted him an enviably broad sense of perspective, seeing himself against a wider timescale than his own life. History became personal for Stanley Rondeau in Spitalfields.

The silk design at the top was commissioned from Anna Maria Garthwaite by Stanley’s ancestor, Jean Rondeau, in 1742. (courtesy of V&A)

4 Wilkes St built by Jean Rondeau in 1723. Pictured here seen from Puma Court in the nineteen twenties, it was destroyed by a bomb in World War II and is today the site of Suskin’s Textiles.

The copy of James Rondeau’s song discovered under a window sill in Cutler St in 1936.

Stanley Rondeau standing in the churchyard near his home in Enfield, at the foot of the grave of John the Sexton’s son and grandson (the author of the song) both called James Rondeau, and who coincidentally also settled in Enfield.

The Return Of Walter Donohue’s Screenwriting Course

Walter Donohue by Sarah Ainslie

We are delighted to announce that – due to popular demand – script editor, producer and luminary of the British cinema, Walter Donohue has agreed to teach another two-day screenwriting course at Townhouse in Spitalfields on the weekend of 18th and 19th April.

Here are some comments by students on Walter’s previous course:

“I just want to say thank you for putting on such a fantastic weekend – it was so, so interesting speaking with like-minded people who share such a love for film and to be able to speak to the wonderful Walter and Mike Figgis and glean some of their vast knowledge. The food was delicious and the setting was ideal, I really appreciate the effort that you put into making it such a fantastic weekend.” MN

“The course itself exceeded my expectations – I learned so many invaluable lessons about screenwriting and the film industry itself. I will take all the new skills into my career. Both Mike Figgis and Walter led an incredibly useful course and truly took their time with each student.” GE

“The weekend spent in the Townhouse was nothing short of wondrous. Walter’s passion for writing and storytelling is infectious. For every story that the students had, Walter had suggestions that took that story to a new level. The man’s knowledge of what is needed in screenwriting and how to pitch, for me, was invaluable. The weekend was two days that I will never forget. I now have the tools and ammunition to start my own personal project. The visit by Mike Figgis was insightful. His views on Hollywood and filmmaking were blunt, informative and most importantly, honest! I could have listened to him talk all day.” JL

WALTER’S EXPERIENCE

In the eighties, Walter began working as a script editor, starting with Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas and Sally Potter’s Orlando. Since then he has worked with some major filmmakers including Joel & Ethan Coen, Wim Wenders, Sally Potter, David Byrne, Mike Figgis, John Boorman, Viggo Mortensen, Alex Garland, Kevin Macdonald, and László Nemes.

For the past thirty years he has been editor of the Faber & Faber film list, publishing Pulp Fiction and Barbie, and screenplays by Quentin Tarantino, Wes Anderson, David Lynch, Sally Potter, and Greta Gerwig & Noah Baumbach, Joel & Ethan Coen, and Christopher Nolan among many others.

Walter also published Scorsese on Scorsese, and edited the series of interview books with David Lynch, Robert Altman, Tim Burton, John Cassavetes, Pedro Almodovar and Christopher Nolan.

THE COURSE

Walter’s course is suitable for all levels of experience from those who are complete beginners to those who have already written screenplays and seek to refresh their practise. The course is limited to sixteen students.

APPROACHES TO SCREENWRITING

Walter says –

“My course is about approaches to writing a screenplay rather than a literal step-by-step technique on how to write.

The objective of my course is to immerse participants in the world of film, acquainting them with a cinematic language which will enable them to create films that are unique and personal to themselves.

There are four approaches – each centred around a particular film which will be the focus of each of the four sessions.

The approaches are –

Structure: Paris, Texas

Viewpoint: Silence of the Lambs

Genre: Anora

Endings: Chinatown

Participants will be required to have seen all four films in advance of the course.”

This is a unique opportunity to enjoy a convivial weekend with Walter in an eighteenth century townhouse in Spitalfields and learn how to approach your screenplay.

Refreshments, freshly baked cakes and lunches are included in the course fee of £350.

Please email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book your place.

Please note we do not give refunds if you are unable to attend or if the course is postponed for reasons beyond our control.

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Viscountess Boudica’s Valentine’s Day

On Valentine’s Day, I cannot help thinking back to the days when we had Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green to make the East End a more colourful place, before she was ‘socially cleansed’ to Uttoxeter

Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green confessed to me that she never received a Valentine in her entire life and yet, in spite of this unfortunate example of the random injustice of existence, her faith in the future remained undiminished.

Taking a break from her busy filming schedule, the Viscountess granted me a brief audience to reveal her intimate thoughts upon the most romantic day of the year and permit me to take these rare photographs that reveal a candid glimpse into the private life of one of the East End’s most fascinating characters.

For the first time since 1986, Viscountess Boudica dug out her Valentine paraphernalia of paper hearts, banners, fairylights, candles and other pink stuff to put on this show as an encouragement to the readers of Spitalfields Life. “If there’s someone that you like,” she says, “I want you to send them a card to show them that you care.”

Yet behind the brave public face, lay a personal tale of sadness for the Viscountess. “I think Valentine’s Day is a good idea, but it’s a kind of death when you walk around the town and see the guys with their bunches of flowers, choosing their chocolates and cards, and you think, ‘It should have been me!'” she admitted with a frown, “I used to get this funny feeling inside, that feeling when you want to get hold of someone and give them a cuddle.”

Like those love-lorn troubadours of yore, Viscountess Boudica mined her unrequited loves as a source of inspiration for her creativity, writing stories, drawing pictures and – most importantly – designing her remarkable outfits that record the progress of her amours. “There is a tinge of sadness after all these years,” she revealed to me, surveying her Valentine’s Day decorations,” but I am inspired to believe there is still hope of domestic happiness.”

Take a look at

The Departure of Viscountess Boudica

Viscountess Boudica’s Domestic Appliances

Mike Henbrey’s Vinegar Valentines

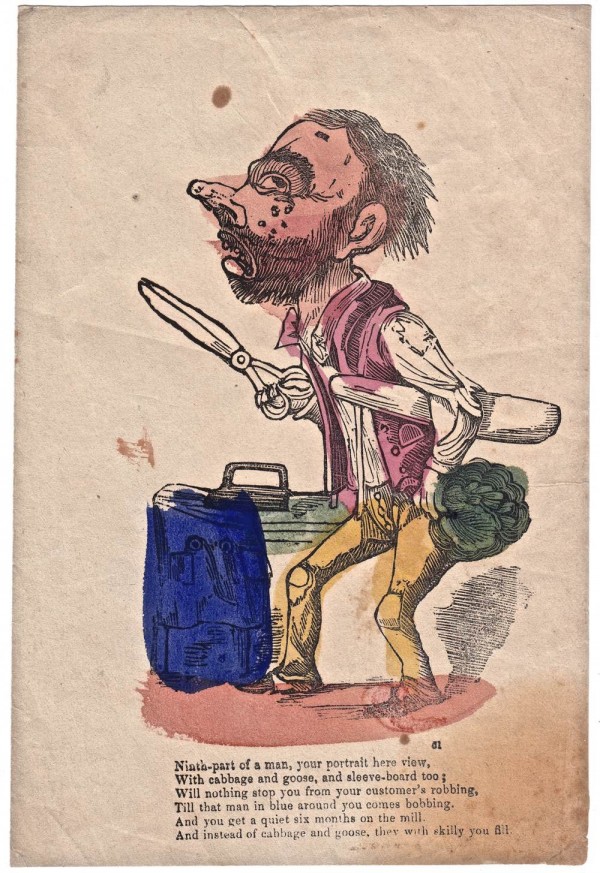

Inveterate collector, Mike Henbrey acquired harshly-comic nineteenth century Valentines for more than twenty years and his collection is now preserved in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute.

Mischievously exploiting the anticipation of recipients on St Valentine’s Day, these grotesque insults couched in humorous style were sent to enemies and unwanted suitors, and to bad tradesmen by workmates and dissatisfied customers. Unsurprisingly, very few have survived which makes them incredibly rare and renders Mike’s collection all the more astonishing.

“I like them because they are nasty,” Mike admitted to me with a wicked grin, relishing the vigorous often surreal imagination at work in his cherished collection – of which a small selection are published here today – revealing a strange sub-culture of the Victorian age.

Images courtesy Mike Henbrey Collection at Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to look at

Joyce Edwards’ Squatter Portraits

John the Fox, 1978

Half a century ago, documentary photographer Joyce Edwards (1925-2024) took these tender portraits of squatters who inhabited empty houses in the triangle of streets next to Victoria Park which had been vacated for the sake of a proposed inner city motorway that was never built. Her pictures are now being shown publicly for the first time at Four Corners in Bethnal Green in an exhibition entitled, Joyce Edwards: A Story Of Squatters, which opens tomorrow and runs until Saturday 20th March.

Joyce Edwards, 1980

Harold the Kangaroo, painter, with his dog Captain Beefheart, 1978

Billy Cowden, Joy Rigard & Jamie, 1978

Henry Woolf, actor, 1974

Beverly Spacie, 1977

Anthony & Andrew Minion, 1980

Elizabeth Shepherd, actor, c. 1970

John Peat, painter,1979

Gary Chamberlin, Beverly Spacie & Howard Dillon, 1977

Julia Clement, 1978

Vanessa Swann & Baz O’ Connell, 1979

Matthew Simmons, 1978

Shirley Robbins, 1977

Tosh Parker, 1977

Sue, 1977

Father & son, 1976

103 Bishops Way E2, Co-op headquarters, 1978

Attempted eviction, 1978

Joyce Edwards, 2012

Photographs copyright © Estate of Joyce Edwards

Joyce Edwards: A Story Of Squatters is at Four Corners, 121 Roman Rd, E2 0QN. Friday 13th February until Saturday 20th March (Wednesday to Saturday, 11am – 6pm)

You may also like to take a look at

Receipts From London’s Oldest Ironmonger

As any accountant will tell you – you must always keep your receipts. It was a dictum adopted religiously by the staff at London oldest ironmongers R. M. Presland & Sons in the Hackney Rd from 1797-2013, where this cache of receipts from the eighteen-eighties and nineties was discovered. They may no longer be of interest to the tax man, but they serve to illustrate the utilitarian beauty of nineteenth-century typographic design and tell us a lot about the diverse interrelated trades which once filled this particular corner of the East End.

You may also like to read about

In Search Of The Rope Makers Of Stepney

Rope makers of Stepney

In Stepney, there has always been an answer to the question, “How long is a piece of string?” It is as long as the distance between St Dunstan’s Church and Commercial Rd, which is the extent of the former Frost Brothers’ Rope Factory.

Let me explain how I came upon this arcane piece of knowledge. First I published a series of photographs from a copy of Frost Brothers’ Album in the archive of the Bishopsgate Institute produced around 1900, illustrating the process of rope making and yarn spinning. Then, a reader of Spitalfields Life walked into the Institute and donated a series of four group portraits of rope makers at Frost Brothers which I publish here.

I find these pictures even more interesting than the ones I first showed because, while the photos in the Album illustrate the work of the factory, in these newly-revealed photos the subject is the rope makers themselves.

There are two pairs of pictures. Photographed on the same day, the first pair taken – in my estimation – around 1900, show a gang of men looking rather proud of themselves. There is a clear hierarchy among them and, in the first photo, they brandish tankards suggesting some celebratory occasion. The men in bowler hats assume authority and allow themselves more swagger while those in caps withhold their emotions. Yet although all these men are deliberately presenting themselves to the camera, there is relaxed quality and swagger in these pictures which communicates a vivid sense of the personality and presence of the subjects.

The other two photographs show larger groups and I believe were taken as much as a decade earlier. I wonder if the tall man in the bowler hat with a moustache in the centre of the back row in the first of these is the same as the man in the bowler hat in the later photographs? In these earlier photographs, the subjects have been corralled for the camera and many regard us with a weary implacable gaze.

The last of the photographs is the most elaborately staged and detailed. It repays attention for the diverse variety of expressions among its subjects, ranging from blank incomprehension of some to the tenderness of the young couple with the young man’s hands upon the young woman’s shoulders – a fleeting gesture of tenderness recorded for eternity.

I was so fascinated by these photographs I wanted to go and find the rope works for myself and, on an old map, I discovered the ropery stretching from Commercial Rd to St Dunstan’s, but – alas – I could discern nothing on the ground to indicate it was ever there. The Commercial Rd end of the factory is now occupied by the Tower Hamlets Car Pound, while the long extent of the ropery has been replaced by a terrace of house called Lighterman’s Court that, in its length and extent, follows the pattern of the earlier building quite closely. At the northern end, there is now a park where the factory reached the road facing St Dunstan’s. Yet the terraces of nineteenth century housing in Bromley St and Belgrave St remain on either side and, in Bromley St, the British Prince where the rope makers once quenched their thirsts still stands.

After the disappointment of my quest to find the rope works, I cherish these photographs of the rope makers of Stepney even more as the best record we have of their existence.

Gang of rope makers at Frost Brothers (You can click to enlarge this image)

Rope makers with a bale of fibre and reels of twine (You can click to enlarge this image )

Rope makers including women and boys with coils of rope (You can click to enlarge this image)

Frost Brothers Ropery stretched from Commercial St to St Dunstan’s Churchyard in Stepney

In Bromley St

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read the original post