Adam Dant’s Map Of St James’ Sq

Adam Dant introduces his Map of St James’ s Sq, completed this spring just in time for inclusion in his MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND. An exhibition of Adam’s maps opens at Rich Mix, Bethnal Green Rd, E1 6LA, this Thursday 4th October from 6-8pm and runs until 21st December. All are welcome.

Click image to enlarge and study the details

“Unlike many other public squares in London, St James’s Square is in possession of a certain aloof – an upper crust aura in keeping with the private finance offices and gentlemen’s clubs that hide behind its well attended facades.

Dirty, smelly dogs are no more permitted into the gardens here than they would be in The London Library, The East India Club or the headquarters of British Petroleum – although my own dog is welcomed as a regular visitor at the nearby Christie’s auction house, possibly by dint of his diminutive size, impeccable manners and Scottish heritage.

Whilst sketching from a bench in the square beneath the statue of King William III, I noticed that not very much appeared to be going on in this square. Such an atmosphere of restraint in a public arena prompts all manner of fanciful notions as to the real identities, activities and motivations of passers-by. Much in the same vein as a novel by London Library habitué Grahame Greene, visitors to St James’s square assume the mantle of the Russian spy visiting a dead letterbox, the covert couple conducting an illicit affair or the minor royal jogging incognito. The real action here has to be invented as nobody is giving anything away.

Secrecy is the order of the day at The Royal Institute of International Affairs, better known as Chatham House whose famous ‘Chatham House Rules’ guarantee speakers at their events the requisite anonymity to encourage the sharing of sensitive information. Until recently, the church of Rome managed to keep their ownership of a handsome townhouse in the square under wraps, having purchased it with shady money from Mussolini.

It is in the same spirit that this topographical depiction of the square prompts the viewer to speculate as to the general goings-on among the characters portrayed and animate their stories, according to the roster of St James’s ‘types’ shown around the border.”

Adam Dant

Adam Dant at Rich Mix 4th October – 21st December

CLICK TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND BY ADAM DANT

Adam Dant’s MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND is a mighty monograph collecting together all your favourite works by Spitalfields Life‘s cartographer extraordinaire in a beautiful big hardback book.

Including a map of London riots, the locations of early coffee houses and a colourful depiction of slang through the centuries, Adam Dant’s vision of city life and our prevailing obsessions with money, power and the pursuit of pleasure may genuinely be described as ‘Hogarthian.’

Unparalleled in his draughtsmanship and inventiveness, Adam Dant explores the byways of English cultural history in his ingenious drawings, annotated with erudite commentary and offering hours of fascination for the curious.

The book includes an extensive interview with Adam Dant by The Gentle Author.

Adam Dant’s limited edition prints are available to purchase through TAG Fine Arts

You may like to take a look at some of Adam Dant’s other maps

Map of the History of Shoreditch

Map of Shoreditch in the Year 3000

Map of Shoreditch as the Globe

Map of the History of Clerkenwell

Map of the Journey to the Heart of the East End

The Coles Of Brushfield St

Kate Cole wrote this account of her ancestors who once lived in Brushfield St. “When I started my family research in the mid-eighties, I quickly discovered the connection to Spitalfields Market,” Kate told me, “And, even though I have visited the redeveloped market, when I think of Spitalfields it is the old market that stays in my mind and which led me to tell the story of my Victorian grocer.”

Kate Cole and her daughter Rose outside the former Cole’s grocery shop in Brushfield St.

I must be amongst a very rare number of twenty-first century Londoners who can visit the East London home of my ancestors and walk in their steps. Many of my Victorian ancestors lived in Bishopsgate in the City of London and Brushfield St in Spitalfields. Whilst I can no longer visit my ancestors’ substantial Bishopsgate home and factory, as it was compulsory purchased and swept away in the 1880s by the Great Eastern Railway so they could build the mighty Great Eastern Hotel in its place, I can still visit my ‘ancestral’ home in Brushfield St on the edge of Spitalfields Market.

Up until the 1870s, Brushfield St was known as ‘Union St East’. Halfway down, on the right-hand side – if you are walking from Bishopsgate – is a parade of shops all dating from the eighteenth century. Many readers may be familiar with the lovely restored Victorian frontage of the food shop A.Gold and the women’s fashion shop next door, Whistles. But have you ever looked above their signage and spotted a small plaque on the wall in between the two? This is from 1871, marking the parish boundary of Christ Church Middlesex and there on the wall, for all of London to see, is the name of my great-great grandfather, R. A. Cole.

In the 1850s, Robert Andrew Cole was a grocer and tea-dealer, living above his shop and trading from the premises which is now Whistles. Robert Andrew, along with his wife, Sarah Elizabeth (née Ollenbuttle) and their five children, William, Sarah, Margaret, Robert and Arthur, all lived in this terrace – first at 23 and then at 25 – for some thirty years from the 1850s until the 1880s, when the market was redeveloped and Robert Andrew Cole retired to Walthamstow. As an aside, I do find it ironic that today’s swanky redeveloped Spitalfields Market is now known as Old Spitalfields Market. In Robert Andrew Cole’s day, it was a brand spanking new, and perhaps an unwanted market with posh new buildings. Its very existence and construction was probably one of the reasons why the Coles gave up their shop and retired to the countryside of Walthamstow.

For many years, Robert Andrew Cole was also a churchwarden of Christ Church, Spitalfields and also the Governor and Director of the Poor of the parish. So he must have been amongst the wealthiest of this East London parish. In circa 1869-1870, Union St East was renamed Brushfield St, and it is possibly the renaming of this street which lead to the church boundary being marked in the wall in 1871. Hence, churchwarden R. A. Cole’s name was recorded for posterity in the brick-work. He must have been a very proud man when his name was unveiled on the terrace where he lived.

However, despite their standing in the community, the Coles’ time in Brushfield St was not entirely happy. Two of the Cole children, Sarah Elizabeth and William Henry, succumbed to a devastating outbreak of scarletina – then a deadly infectious disease. Both children were buried in Tower Hamlets Cemetery on 2nd August 1857. William was aged only twenty-two months and Sarah was a month short of her fourth birthday. One can only imagine the pain and horror experienced by their parents, along with the fear that their only surviving child, Robert, then aged five, might also fall victim to the terrible disease.

It must have been an awful time for this one Victorian family living in the shadows of Christ Church Spitalfields and the Fruit & Vegetable Market. However, their son Robert, did not become another victim (for, if he had, I would not be writing their story, as he is my great-grandfather). Eight months after burying their two children, a new child, Margaret was born, and a further year later, Arthur. Sadly, Margaret also did not survive childhood and once again, in 1869, the Cole family of Union St East buried another one of their own in Tower Hamlets Cemetery.

I have often pondered the fate of this small East End family. Of the five children, only two survived into adulthood and, of those two, only one had children of his own. Arthur Cole died a bachelor in his fifties and was buried in the second Cole family grave in Tower Hamlets Cemetery alongside his mother, grandparents, great-aunts, and great-uncles – true Londoners who worked, lived and died in the East End of the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Robert Andrew Cole, grocer and tea-dealer of Spitalfields Market, was buried in the same grave as his three children who had not survived childhood. While Robert Cole, the only child of Robert and Sarah Cole who went on to marry and father his own children, married Louisa Parnall, a member of a fantastically successful Welsh family of industrialists and philanthropists who had a substantial clothing factory on Bishopsgate.

When you are next in Brushfield St, stand and look up at the plaque marking the parish boundary of Christ Church, Middlesex. Then look down into the windows of Whistles clothes shop. The funeral processions of the Cole children must have stopped here on their way to Christ Church, before going to Tower Hamlets Cemetery. Imagine the tragedy and triumph that went on between those four walls and the drama of the daily family life of the Victorian grocer and tea-dealer, Robert Andrew and Sarah Elizabeth Cole.

Robert Andrew Cole, born 10th February 1819, Anthony St, St George in the East, baptised 7th March 1819 in the parish church of St George in the East. Married 25th December 1850 St Thomas’ Church, Stepney to Sarah Elizabeth Ollenbuttle. Died March 1895 in Walthamstow. Buried in one of two Cole family graves in Tower Hamlets Cemetery. Grocer and tea-dealer of Spitalfields Market for over thirty years. Churchwarden of Christ Church Spitalfields and Governor and Director of the poor of the parish.

Robert Cole, eldest child of Robert Andrew and Sarah Elizabeth Cole, born 4th May 1852 in Tunbridge Wells. Married 11th January 1880 to Louisa Parnall (great-niece of Robert and Henry Parnall of Bishopsgate). Died 17th June 1927 in Raynes Park, South London. Buried in Putney Vale Cemetery. Grocer and teadealer.

Margaret Cole, baptised 28th March 1858 at Christ Church, Spitalfields. Buried 20th January 1869 in Tower Hamlets Cemetery aged eleven years. The child in this photo looks to be about seven or eight years old, which dates all three photos to approximately the mid-1860s.

Robert Cole in 1879.

Louise Parnell – This tintype photo and the one of Robert above were possibly taken at their betrothal, before their marriage in January 1880.

The locations of the Coles’ business in Brushfield St and the Parnell’s business in Bishopsgate.

Philip Marriage’s photo of Brushfield St in 1985 with the former Coles premises indicated by the awnings.

Brushfield St in 1985, looking from the east.

The boundary stone with R. A. Cole’s name is on the top left of this picture from the eighties.

The boundary stone of 1871 in Brushfield St with the name of R.A.Cole.

Kate and her daughter Rose are the sixth and seventh consecutive generations of their family to work in the Bishopsgate area. Kate works in Finsbury Sq and Rose has just started in Finsbury Circle.

Archive photographs of Brushfield St © Philip Marriage

Cole family photographs © Kate Cole

You might like to take a look at Kate Cole’s blog Voices of Essex Past

Samuel Wilson’s Ledger

October is Huguenot Month in Spitalfields and this year’s theme is Women & Power including walks exploring Spitalfields Sisters, The Work & Lives of Remarkable Women.

Kate Wigley, Director of the School of Textiles, introduces the rare survival of an early nineteenth century weaver’s working diary. She will be speaking about Samuel Wilson’s ledger at 2pm on Saturday 20th October at Christ Church, Spitalfields. Click here for tickets

When my eyes fell upon the weaving ledger of Samuel Wilson (1792-1881) for the first time, I was struck not only by the captivating fabrics but also the beauty of the detailed records of production and manufacturing processes. Each line, carefully written in exquisite copper plate, sits alongside its own delicate textile production sample.

Written between 1811 and 1825, the ledger is a record of Samuel Wilson’s apprenticeship to his brother’s company, Lea & Wilson of 26 Old Jewry, Cripplegate, alongside an account of his personal exploration of weaving processes. When he embarked on his apprenticeship in 1806, Samuel began a comprehensive study of the process of silk manufacture – from throwing to weaving.

Samuel’s brother, Stephen Wilson was known for introducing an early version of the Jacquard loom into England in 1820 through his own patent. He was already well established within the London silk industry and had expanded his business with additional premises in Streatham. In the pages of the ledger, it is evident how mechanical improvements were contributing to the development of the Joseph Marie Jacquard’s new manufacturing technology.

Samuel Wilson became a leading force in the London silk industry and worked his way up to the position of Upper Bailiff in the Worshipful Company of Weavers. By 1838, the power of Samuel’s Wilson wider influence was recognised when he was elected Lord Mayor of the City of London.

Although his ledger is in private hands, I have been granted the opportunity of studying it in detail after I first encountered while researching early nineteenth century looms with textile historian, Mary Schoeser. Turning the pages carefully, we were both surprised how the ledger touched us and, without quite realising it, we found we had made a silent pact to uncover the secrets held within.

The opening pages are devoted to a discourse on how to create a perfect woven circle and the many minor adjustments to the ‘tyes’ and ‘sett’ that Samuel had to make on a loom to achieve this. It reveals the remarkable technological changes weavers experienced in the first three decades of the nineteenth century. Part-way, the ledger includes patterns for silk scarf designs. A tantalisingly small cutting of a hand-woven red and yellow silk for ‘chair bottoms for one of her majesty’s rooms in the Castle Windsor’ in 1816 is pinned carefully to the left-hand corner of a page.

Samuel Wilson’s apprenticeship record is a rare discovery that offers a unique view of the workings of the London silk industry in his era. More importantly, Samuel shares his own experiments and personal findings alongside accounts of disputes over weavers’ pay, dye recipes and client orders. The fabric samples and text are of great interest in their own right, but together they comprise an exceptional window into the development of a period in London’s textile history that is largely neglected. Through his personal ledger, we can read Samuel Wilson’s personal thoughts and hear his voice too.

Photographs copyright © Kate Wigley

Click here to see the full programme of events in this year’s Huguenot Month

You may also like to read about

Joginder Singh’s Boy

Spitalfields Life Books will be publishing A MODEST LIVING, Memoirs of Cockney Sikh by Suresh Singh in October. Here is the fourth instalment and further excerpts will follow over coming weeks.

In this first London Sikh biography, Suresh tells the story of his family who have lived in their house in Princelet St for nearly seventy years, longer I believe than any other family in Spitalfields. In the book, chapters of biography are alternated with a series of Sikh recipes by Jagir Kaur, Suresh’s wife.

You can support publication by pre-ordering a copy now, which will be signed by Suresh Singh and sent to you on publication.

Click here to order a signed copy of A MODEST LIVING for £20

Suresh Singh & Jagir Kaur at 38 Princelet St this summer (Photograph by Patricia Niven)

Me & Dad

As a child, I lived in awe of Dad, to me he was god. He was a very strong man and occasionally I would accompany him to the building sites where he worked. The Irish builders loved seeing us, father and son together, calling me ‘Jo’s boy.’ They would give me ten pence at the end of the day for helping and say, ‘He’s your boy, he’s our boy.’ I was so proud of Dad.

When he did repairs around the house, I passed him the hammer and carried the nails and I loved being around him. I believed nothing could hurt me if he was there. I felt safe anywhere he was. He had such a strong presence, making me feel as if I was in the company of someone holy.

Mum was affectionate and warm. She was a large woman who was very cuddly and I would always be hugging her. As the youngest boy, I spent all my time with her. She washed my hair every morning in the kitchen and every evening in front of the fire. It was a ritual – undoing the plait, combing the hair forward and washing it. Sometimes she would wash it with yoghurt, then massage mustard oil all the way down through the hair. Afterwards, she combed it, first in front and then flicking it back to comb it from behind. Finally, she would plait it into one long plait, wrap it all the way round into a big bob, cover it with a hanky and tie with a ribbon at the end to hold it all together. If she found an elastic band, she might encapsulate the bob to hold it in shape. Mum loved to see my hair tied up in a big knot and I think it broke her heart when it was cut off later. She missed it so.

From the age of two, I had asthma. It became more severe as I grew. I used to sleep with Mum when I was little and she would rub my chest with Vick’s eucalyptus cream and heat Wright’s Coal Tar in a vaporiser to clear my lungs. She was always making me jumpers and dressing me up. She liked putting me in dresses that she made. Visitors asked, ‘Is Suresh a girl or a boy?’ Mum loved sewing things, making clothes and other stuff for the home from bits and bobs of fabric that workers in the local rag trade gave her. ‘There’s a bit of lining left over,’ they would say, ‘you can have it.’ Dad bought old printed cotton curtains in the Sunday market and she adjusted them, hemming and sewing rings onto them.

Dad lit fires in the winter and he swept the chimney himself. Even though we covered everything, the soot got everywhere. When we all ate together on the floor in front of the fire, using newspaper as a tablecloth, Dad recited hymns from Guru Granth Sahib, the holy book. He always told us stories of the gurus, especially Guru Ravidas Ji the shoemaker and Guru Nanak, the first guru and founder of Sikhism.

Every day, I watched him leave and return from shoe shining on Liverpool Street station or labouring on building sites, then doing odd jobs for family and friends to make sure we were well fed. He could work all day on a building site and then go to shine shoes on Liverpool Street to make a bit extra.

Although our clothes might have been secondhand from the flea market or altered and patched up, they were always clean. Mum used to heat them in a pan with washing powder. Occasionally they boiled over, and the soap suds spilt all over the cooker and onto the floor.

My earliest memory was of playing in the yard on my bike which Dad got me in the Brick Lane market. Everyone always showed me great affection and, because I was the youngest boy, I was very well treated. It meant a lot to Mum and Dad that I was the one who had the Sikh hair, the kesh. I had to stay at home because I was ill and, even after I got married and everybody else moved out, I lived with them in Princelet Street right up to the end.

Some family and friends suggested that maybe my long hair was the reason my health was not good. It was down to my knees by then. I was taken to the doctor in Brune Street. Dr Gottlieb asked Mum, ‘Mrs Kaur, can you wait outside a minute?’ Then he spoke with me, ‘What’s the matter, Suresh?’ he asked. I started to cry and said, ‘I want to cut my hair off!’ My fear was that I would get bullied at secondary school and it was really hard to manage. Mum’s health was not good and she found it difficult to comb and wash it every morning and evening. Dr Gottlieb brought Mum in again and told her, ‘You’ve got to cut his hair off.’ Mum said, ‘Oh, that’s sad,’ but I was grateful to Dr Gottlieb for supporting me.

Dad took me into the yard and cut all my hair off with a pair of scissors. While he was doing it, he chanted ‘Wah Hey Guru.’ I wonder if it reminded him of when his hair was cut off in Glasgow. Mum collected my hair and treasured it in a hidden place in the house for more than a year, bundled in a cloth. Then one evening she took me for a walk to Tower Bridge and, producing the bundle from her handbag, released it with both hands over the parapet in silence into the Thames. Then she said to me, ‘Hun Chuyla,’ meaning ‘Let’s move on.’

Once my hair was cut off, I felt a proper jack the lad, you know? I played in the street with the Bengali children who had recently arrived from Bangladesh. They loved marbles and we played a lot of football in Princelet Street. We used to climb onto the garden walls of the houses in Fournier Street, walking from Brick Lane to Commercial Street.

Me in the yard with my topknot

Me in Weavers Fields after I lost my topknot

Mum & Dad in Princelet St

Click here to order a signed copy of A MODEST LIVING for £20

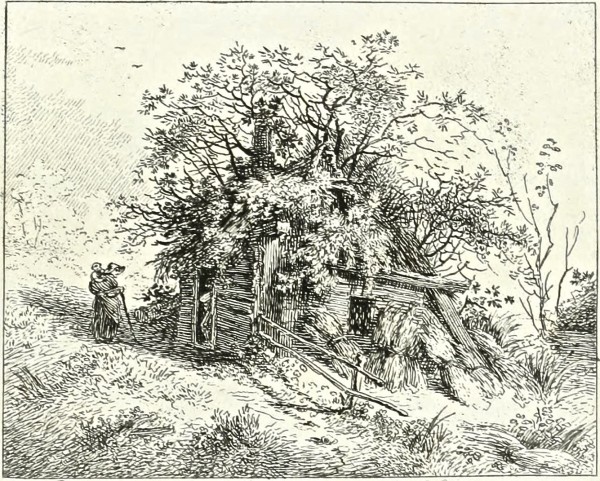

John Thomas Smith’s Rural Cottages

Near Battlebridge, Middlesex

As September draws to a close and autumn closes in, I get the urge to go to ground, hiding myself away in some remote cabin and not straying from the fireside until spring shows again. With this in mind, John Thomas Smith’s twenty etchings of extravagantly rustic cottages published as Remarks On Rural Scenery Of Various Features & Specific Beauties In Cottage Scenery in 1797 suit my hibernatory fantasy ideally.

Born in the back of a Hackney carriage in 1766, Smith grew into an artist consumed by London, as his inspiration, his subject matter and his life. At first, he drew the old streets and buildings that were due for demolition at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Ancient Topography of London and Antiquities of London, savouring every detail of their shambolic architecture with loving attention. Later, he turned his attention to London streetlife, the hawkers and the outcast poor, portrayed in Vagabondiana and Remarkable Beggars, creating lively and sympathetic portraits of those who scraped a living out of nothing but resourcefulness. By contrast, these rural cottages were a rare excursion into the bucolic world for Smith, although you only have to look at the locations to see that he did not travel too far from the capital to find them.

“Of all the pictoresque subjects, the English cottage seems to have obtained the least share of particular notice,” wrote Smith in his introduction to these plates, which included John Constable and William Blake among the subscribers, “Palaces, castles, churches, monastic ruins and ecclesiastical structures have been elaborately and very interestingly described with all their characteristic distinctions while the objects comprehended by the term ‘cottage scenery’ have by no means been honoured with equal attention.”

While emphasising that beauty was equally to be found in humble as well as in stately homes, Smith also understood the irony that a well-kept dwelling offered less picturesque subject matter than a derelict hovel. “I am, however, by no means cottage-mad,” he admitted, acknowledging the poverty of the living conditions, “But the unrepaired accidents of wind and rain offer far greater allurements to the painter’s eye, than more neat, regular or formal arrangements could possibly have done.”

Some of these pastoral dwellings were in places now absorbed into Central London and others in outlying villages that lie beneath suburbs today. Yet the paradox is that these etchings are the origin of the romantic image of the English country cottage which has occupied such a cherished position in the collective imagination ever since, and thus many of the suburban homes that have now obliterated these rural locations were designed to evoke this potent rural fantasy.

On Scotland Green, Ponder’s End

Near Deptford, Kent

At Clandon, Surrey – formerly the residence of Mr John Woolderidge, the Clandon Poet

In Bury St, Edmonton

Near Jack Straw’s Castle, Hampstead Heath

In Green St, Enfield Highway

Near Palmer’s Green, Edmonton

Near Ranelagh, Chelsea

In Green St, Enfield Highway

At Ponder’s End, Near Enfield

On Merrow Common, Surrey

At Cobham, Surrey – in the hop gardens

Near Bull’s Cross, Enfield

In Bury St, Edmonton

On Millbank, Westminster

Near Edmonton Church

Near Chelsea Bridge

In Green St, Enfield Highway

Lady Plomer’s Place on the summit of Hawke’s Bill Wood, Epping Forest

You may also like to take a look at these other works by John Thomas Smith

John Thomas Smith’s Ancient Topography of London

John Thomas Smith’s Antiquities of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

Dr Legg, General Practitioner

Contributing Writer Gillian Tindall celebrates the career of Leonard Fenton, an East End boy better known as ‘Dr Legg,’ who has recently returned to Eastenders at the fine age of ninety-two years old. Gillian’s books include The House by the Thames and A Tunnel Through Time.

Leonard Fenton as Dr Legg with June Brown as Dot Cotton (reproduced courtesy BBC)

When Dr Legg, the General Practitioner in Eastenders, retired in 1997, there was universal regret among viewers – even though they could see he was already older than any real-life General Practitioner would be. Afterwards, he continued to be referred to as an off-stage presence, like a benign Scarlet Pimpernel, and he made occasional informal reappearances – most notably for the stage-funeral of Mark Fowler in 2004, with whom he had once had ferocious doctorly words about heroin addiction and, in 2010, to counsel Dot Branning about a supposed Romanian foundling.

In real life, Dr Legg is the actor Leonard Fenton. Although his Eastenders‘ role has been the one for which he has been widely celebrated (and even accosted in the street and the Underground by people so convinced of the reality of soaps that they ask for friendly medical advice) he has a life-time of other roles to his credit. One of those actors who was always in work and much esteemed by other professionals, Len has done seasons with the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company, worked with Orson Welles, with Jonathan Miller and Samuel Beckett – who personally chose him in 1979 to play opposite Billie Whitelaw in Happy Days at the Royal Court.

His last stage roles were the Duke in The Merchant of Venice at Stratford-on-Avon in 2008 and the demanding part of Vincentio in The Taming of the Shrew at the Aldwych Theatre in London in 2009. By then Len was eighty-three years old, but you would never have guessed it. He went on for several more years specialising in ‘old rabbis’ and has only now taken to retirement in the actors’ home at Denville Hall, because his diabetes needs more careful management than he can give it alone.

The kindly Dr Legg in East Enders is obviously Jewish and the early lives of the doctor and the actor paralleled each other. Dr Legg was born in the East End, a bright boy who got a scholarship to a Grammar School and then to medical school, but had preferred to remain close to his roots in the fictional East London district of `Walford’ rather than moving out to a polite suburb.

Similarly, Len Fenton was born during the General Strike of 1926 in a little house in Duckett St, Stepney Green, that his parents and elder sister shared with relatives. When he was eleven, he won a Junior County scholarship to Raines School for Boys in Arbour Sq. A surviving school report, under the name Leonard Feinstein, describes him as “A quiet intelligent pupil. Gives no trouble and works well.” The same report shows that he was particularly good at drawing, singing and languages, but as he showed an aptitude for maths too, plus ‘satisfactory’ work at Chemistry and Physics, the headmaster urged him towards engineering – a destiny that took Len some years and quite a bit of enterprise to escape.

The heart of the Jewish East End in the twenties and thirties was in Whitechapel and Spitalfields. Half a mile away, in Duckett St there was only one other Jewish household besides Len’s family, although Len recalls a big block of flats on Stepney Green itself that was “full of our lot. I would rather liked to have lived there.” Possibly it was the presence of this block that drew Mosleys’ Blackshirts down to Stepney Green for a series of threatening marches that were to culminate in the Battle of Cable Street. As a small boy, Len remembers his mother standing in the upstairs window of their house with a baby – one of Len’s younger sisters – in her arms, watching Mosley giving a speech at the corner about how all Jews had substantial bank balances. At this point, she yelled down at him “Sir Oswald, would you like to see my fucking bank balance?” Her husband worked in the garment trade and, like most people in their position, they lived hand to mouth. Various neighbours, who were inclined to side with Mosley in those uncertain times, hastily cried “No, no, Fanny, we don’t mean you!”

Len’s mother had arrived in London as a baby, circuitously, via New York, at the beginning of the twentieth century. She was working in a box factory when she met her husband. Both sets of grandparents were immigrants from Eastern Europe, mother’s from Riga and father’s from Lithuania, and all that generation spoke Yiddish as their household tongue. The family name was originally, Len thinks, something like Resnik, a Russian-Yiddish term to do with tailoring, but it just happened that the neighbour who helped Len’s grandfather to register in London when he arrived in the 1890s suggested ‘Feinstein’ as a suitable name and it was accepted. The change to Fenton happened during the Second World War, when Len’s elder sister Sylvie convinced their father that it would be a good idea. However, the cousins living on the ground floor of the same house, including little Arnold who was six months younger than Len and his constant playmate, did not change their name. Arnold Feinstein, another scholarship boy, grew up to be a distinguished academic scientist and the husband of Elaine Feinstein, the poet. There are many routes out of the ghetto, but the Fenton-Feinstein families have always remained close.

Grandparents and uncles were important too. Len’s mother’s mother, who had been widowed in New York with the baby, come to London and remarried, lived at Bow. Neighbours of theirs organised a synagogue in their front room where the family foregathered on Saturdays. It was from here that an uncle took Len, then aged ten or eleven, on a trip to Watford to hear Thomas Beecham conducting Bizet’s First Symphony in C – for Len, a revelatory experience about what music could be. But, sadly, this thoughtful relative later became known to Len and his sisters as ‘bad uncle’ because he tried to convince Len that he could neither draw and paint, nor sing well enough to envisage it as a career – both of which no-doubt-well-intentioned judgements were untrue.

Len was thirteen in 1939, at the point when the whole Jewish East End began to be swept away, first by war and then by the social changes that war brought. Raines School was evacuated to various places near the south coast: hardly the ideal location in view of the threat of invasion, but such a hasty relocation was common in those times. By the time Len returned to battered and blitzed Stepney towards the end of the war, he was a tall and handsome seventeen-year-old – and his feisty mother, with whom he had not lived since he was a child, was suffering with tuberculosis and possibly diabetes as well. There was no NHS yet but, even if there had been, not a great deal could have been done for her. She died in 1945 and it was the eldest sister Sylvie who took on the maternal role for their father, for Len, his younger brother Cyril (who also died young) and the two pretty and ambitious younger sisters, Corinne and Annie.

National Service loomed at eighteen for all young men of Len’s generation yet, instead of joining the Army as a squaddie, Len was sent, on his head-master’s recommendation and Government approval, to do a two-year degree in Engineering at Kings’ College. He did not relish it at all, but it meant that, when the Army finally claimed him at age twenty, he was given a commission in the Royal Engineers – a new world for him. “I really enjoyed myself,” he recalled, “As an officer I could just oversee things and sign off the paper, while the NCOs did all the work!”

Len’s Army experience led him to five years in a civil engineering job in Westminster. This was still unsatisfying for Len, even though the firm in question seems to have been extraordinarily tolerant of their amiable but undevoted employee. Len found that he could take long, dreamy lunch hours walking round the London parks. By then he was living in Clapton and discovered, while changing from tube to bus at Aldgate on his evening commute, that Toynbee Hall ran courses in art and music. He started spending his evenings there, as many other aspirant East Enders had done before him – and a new life began. A starring role singing in a Christmas performance led to the offer of a place at the Webber-Douglas theatrel school, and the boy from Stepney was re-born as an actor and never looked back.

“I was older than most people at drama school,” he explained, “That was useful and I soon learnt to age myself up – I loved making-up.” A Spotlight award in his final year set Len off on a career playing character roles – fulfilling even if he never achieved a minor ambition to take the part of Baron Hard-Up in pantomime. “Trouble is, people don’t associate Dr Legg with slapstick,” he confessed.

Did becoming a celebrity in such a long-running soap affect his chances of other roles? Len feels that it may have kept him out of the theatre, but one would hardly think so given the stage successes of his last years in the profession. Oddly, Dr Legg is almost the only role in Len’s career which was not a character part. “The character wasn’t written to any great depth,”says Len, “so inevitably what came over on TV was a lot of me. I sometimes used to slip in words of my own that weren’t in the script! I think they should have given me a proper wife, though, not just a dead one.” Mrs Legg was supposed to have been a nurse, killed long ago by a land-mine.

In real life Len married, aged almost forty, to a professional cellist, Madeline Thorner, considerably younger than him. Three sons and a daughter arrived in quick time, in their house in Hampstead Garden Suburb that was a far cry from Duckett St. Although the marriage eventually foundered, Len and Madeline remain friends and it was she who managed to get him into Denville Hall.

Any regrets? “Well, if I’d know how well my voice would last,” he admitted, “I’d have been a singer.” Len does still sing beautifully, even in his ninth decade, and possesses an extraordinary ability to imitate dogs and cats well enough to fool the animals themselves. His ability to paint and aptitude for drawing that his headmaster and uncle dismissed long ago came to the fore during Len’s years as Dr Legg, and he continues to paint. The aura of cheerful interest in life, that stood him in such good stead as a small boy in Stepney, still surrounds Len today.

Leonard Fenton

Leonard’s mother and father with his elder sister Sylvie as a baby

Leonard and his sister Sylvie with their Uncle

Leonard Fenton’s publicity shot as a young actor

Leonard playing older than his years in the seventies

Leonard’s publicity shot in the eighties

Leonard in the West End

Leonard’s sketch of Samuel Beckett, done while rehearsing Happy Days at the Royal Court in 1979

You may also like to read about

Morris Goldstein, the Lost Whitechapel Boy

Charlie Chaplin in the East End

David Garrick at Goodman’s Fields Theatre

At the Pavilion Theatre, Whitechapel

Mr Pussy At Hatchards

Please join me at 6:30pm this Monday 1st October to launch THE LIFE & TIMES OF MR PUSSY, A Memoir of a Favourite Cat at Britain’s oldest bookshop, Hatchards in Piccadilly, where I will be reading stories from the book and signing copies. Admission is free and all are welcome.

Click here to order a signed copy for £15