The Curse Of Vicky’s Ticker

In these pages in 2012, Roger Clarke first revealed the intriguing tale of a gold pocket watch presented by Queen Victoria to an eleven-year-old Shoreditch clairvoyant. The watch – known as Vicky’s Ticker – went missing in 1962 when it was stolen from the London College of Psychic Studies, yet since Roger wrote his story for Spitalfields Life it has inexplicably reappeared.

Once I held it in my hand, I was aware of the weight of it. I was standing in a small downstairs room at Bonhams in South Kensington holding a Victorian gold pocket watch. Yet the weight I felt was not that of the precious metal or the intricate mechanics of its system, but of the significance of those whose hands through which the watch had passed: Queen Victoria, two celebrated psychics, a newspaper editor who went down in the Titanic and the thief who stole it fifty years ago.

Here is the entry in Bonham’s catalogue:

LOT 19: AN 18K GOLD KEY WIND OPEN FACE POCKET WATCH, Circa 1840 (£500–700)

Two engraved inscriptions: ‘Presented by Her Majesty to Miss Georgiana Eagle for her Meritorious & Extraordinary Clairvoyance produced at Osborn House, Isle of Wight, July 15th 1846′ and ‘Presented by W.T Stead to Mrs Etta Wriedt through whose mediumship Queen Victoria’s direct voice was heard in London in July 1911.’

I first came across the name of Georgiana Eagle, Wizard Queen & Mesmerist, while researching my book A Natural History of Ghosts – and as a Shoreditch resident myself – I was naturally intrigued by her. Dalston was a Victorian nexus of young female psychics, including the infamous Florence Cook in the eighteen seventies, and there was a very famous Dalston spiritualist group at the time many of whose members worked on the railways – two recently-built spurs (now the overground) had opened up the area and were instrumental in making Dalston popular for séances. It was a new territory, opening new doors into the other world. However it seems an even younger East London psychic proceeded Miss Cook by several decades amongst the furniture-making factories and leather-working rooms of Shoreditch.

Georgiana Eagle was born on November 28th 1834 and baptised at St Leonard’s Church. Her grandfather owned a pub in the parish and the family were of Huguenot descent. She lived with her father Barnardo Eagle in Holywell Place. He was a professional stage magician and the family led a nomadic existence as travelling players. In 1839, he was describing himself as ‘The Royal Wizard of the South’ and in the Birmingham Journal of November 23rd of that year claimed he had performed for ‘His late Majesty and Queen Adelaide, Duchess of Saxe-Weimar, Her Majesty Queen Victoria, The Duchess of Kent and numbers of the nobility.’

After the death of her mother, eight-year-old Georgiana stayed with her father while the rest of her siblings were packed off to live with their grandparents in 36 Coleman St. She was a willing participant in her father’s stage act of ‘Hundred feats of mighty magic’. He was a sceptic who revealed deception and his show, The Mysterious Lady, which was devoted to exposing the clairvoyance claims of mesmerists – proved immensely popular. Little Georgiana was the star and she performed for Queen Victoria at Osborne House when Prince Albert was still alive, receiving the gift of the gold watch from the monarch. Victoria’s journals show she gave similar watches to other children of Georgiana’s age and I believe Georgiana had it engraved after that event at Osborne House in 1846. This is the ill-fated watch that was subsequently stolen from the College of Psychic Studies in September 1962.

One morning last year, I received a call from a relative in the antiques business who was monitoring sales of objects connected to the Isle of Wight where we both grew up. He had learnt about the sale of a watch. I went in one day in January for a viewing and sat in a small windowless, fortified room as a young man brought it in. There was absolutely no doubt about it. This was Vicky’s Ticker – the watch given to Georgiana by Queen Victoria which has not been seen or heard of since 1962. It had been discovered among the effects of a jeweller from Manchester at his decease by his relatives, who had no idea of its tainted provenance.

There is a contemporary mention of Victoria’s gift of the watch to Georgiana in the Northampton Mercury in 1849. ‘On Monday last, a theatre suddenly upreared its tawdry head in the market square, decorated with pictures representing Miss Georgiana Eagle in trunk hose and flesh tights, in the act of receiving a splendid gold watch from Her Majesty Queen Victoria.’

A remarkable thing happened. In 1850, Barnardo Eagle advertised private clairvoyance sessions ‘to the nobility and gentry’ in Brighton. At a meeting in Edinburgh in November 1852, around sixty people were invited to experience Georgiana’s powers of mediumship and mesmerism. Whether this conversion was heartfelt or genuine, we will probably never know. It could have been simply that Barnardo was commercially savvy and he saw the wind was blowing in favour of psychics. Yet his journey from sceptic to believer is the reason that the watch is so precious to the College of Psychic Studies.

Those who were shocked by Barnardo’s apparent betrayal of his rational beliefs blamed him for dragging his eighteen year-old daughter along with him. It did not go well for either of them. By 1853, he had abandoned the profession and reverted to the family occupation, buying the licence to the Brown Bear Tavern near the British Museum. His infant daughter Rosabel died and was buried in a public grave, indicating the family’s reduced state at this time. Yet by 1855 they were back on the road, offering clairvoyance once again.

There was a late resurgence in their fame. The hiatus appears to have restored their public reputation now belief in psychic phenomena had became widespread. Then tragedy struck when Barnardo died onstage during his act. A few weeks later – while her father was barely cold in the ground – Georgiana married a Drury Lane scene-painter. She was now performing as Madame Card, Wizard Queen and Mesmerist and living happily with her husband in Cheltenham, until he was committed to a lunatic asylum in Sussex where he died seven months later.

She married a music professor from Islington and they toured together. He accompanying her act with musical numbers and they were reviewed quite favourably by the Evening Standard. Georgiana was by now an accomplished hypnotist and ‘performed with a dexterity that is scarcely surpassed by any other male conjurer’ Unfortunately, the music professor – a volatile character who got in trouble with the law over his temper – also died young and Georgiana was widowed for a second time by the age of forty-seven. She married a draper twenty-five years her junior, and eventually died in Muswell Hill of ‘senile decay’ in March 1911.

Within months of Georgiana’s death, the watch fell into the hands of the newspaper editor W.T. Stead who gave it to Etta Wriedt, a medium who used it to channel the spirit and voice of Queen Victoria in London in July 1911. When Stead drowned on the Titanic, Wriedt presented the watch to the London College of Psychic Studies.

The colourful history of this little timepiece might tempt the credulous to believe it has a curse attached to it – though why that should be, I have no explanation. I attended the ceremony marking the return of the watch at the College of Psychic Studies and afterwards talked with a throng of interested parties. ‘We think you were guided,’ suggested a couple of mediums but naturally I could not say. Yet it is very strange that I should write on the subject for Spitalfields Life and then find it.

I do not feel my business with Georgiana Eagle has quite finished yet.

Georgiana Eagle, Wizard Queen & Mersmerist of Shoreditch

Inscription of July 1846

Inscription of July 1911

St Leonard’s Church where Georgiana Eagle, Wizard Queen & Clairvoyant Mesmerist, was baptised

Dalston became a nexus for female psychics in the eighteen seventies due to improved transport links

Barnardo Eagle, the Royal Wizard of the South (Courtesy of Senate House Library)

Advertisement for a performance by Barnardo and Georgiana Eagle in Plymouth

Georgiana Eagle commonly performed under the stage name of Madame Gilliland Card (Poster courtesy of British Museum)

Etta Wriedt used Vicky’s Ticker to channel the spirit and voice of Queen Victoria in London in 1911

Journal of Spiritualism, Psychical, Occult & Mystical Research (Courtesy London College of Psychic Studies)

Roger Clarke wishes to thank Vivienne Roberts, College Curator & Archivist at the London College of Psychic Studies for her research

You may also like to read about

Upon The Nature Of Gothic Horrors

I believe I was born with a medieval imagination. It is the only way I can explain the explicit gothic terrors of my childhood. Even lying in my cradle, I recall observing the monstrous face that emerged from the ceiling lampshade once the light was turned out. This all-seeing creature, peering at me from above, grew more pervasive as years passed, occupying the shadows at the edges of my vision and assuming more concrete manifestations. An unexpected sound in my dark room revealed its presence, causing me to lie still and hold my breath, as if through my petrified silence I could avert the attention of the devil leaning over my bedside.

When I first became aware of gargoyles carved upon churches and illustrated in manuscripts, I recognised these creatures from my own imagination and I made my own paintings of these scaled, clawed, horned, winged beasts, which were as familiar as animals in the natural world. I interpreted any indeterminate sound or movement from the dark as indicating their physical presence in my temporal existence. Consequently, darkness, shadow and gloom were an inescapable source of fear to me on account of the nameless threat they harboured, always lurking there just waiting to pounce. At this time of year, when the dusk glimmers earlier in the day, their power grew as if these creatures of the shades might overrun the earth.

Nothing could have persuaded me to walk into a dark house alone. One teenage summer, I looked after an old cottage while the residents were on their holiday and, returning after work at night, I had to walk a long road that led through a deep wood without street lighting. As I wheeled my bicycle up the steep hill among the trees in dread, it seemed to me they were alive with monsters and any movement of the branches confirmed their teeming presence.

Yet I discovered a love of ghost stories and collected anthologies of tales of the supernatural, which I accepted as real because they extended and explained the uncanny notions of my own imagination. In an attempt to normalise my fears, I made a study of mythical beasts and learnt to distinguish between a griffin and a wyvern. When I discovered the paintings of Hieronymous Bosch and Pieter Breughel, I grew fascinated and strangely reassured that they had seen the apocalyptic visions which haunted the recesses of my own mind.

I made the mistake of going to see Ridley Scott’s The Alien alone and experienced ninety minutes transfixed with terror, unable to move, because – unlike the characters in the drama – I was already familiar with this beast who had been pursuing me my whole life. In retrospect, I recognise the equivocal nature of this experience, because I also sought a screening of The Exorcist with similar results. Perhaps I sought consolation in having my worst fears realised, even if I regretted it too?

Once, walking through a side street at night, I peered into the window of an empty printshop and leapt six feet back when a dark figure rose up from among the machines to confront my face in the glass. My companions found this reaction to my own shadow highly amusing and it was a troubling reminder of the degree to which I was at the mercy of these irrational fears even as an adult.

I woke in the night sometimes, shaking with fear and convinced there were venomous snakes in the foot of my bed. The only solution was to unmake the bed and remake it again before I could climb back in. Imagine my surprise when I visited the aquarium in Berlin and decided to explore the upper floor where I was confronted with glass cases of live tropical snakes. Even as I sprinted away down the street, I felt the need to keep a distance from cars in case a serpent might be lurking underneath. This particular terror reached its nadir when I was walking in the Pyrenees, and stood to bathe beneath a waterfall and cool myself on a hot day. A green snake of several feet in length fell wriggling from above, hit me, bounced off into the pool and swam away, leaving me frozen in shock.

Somewhere all these fears dissolved. I do not know where or when exactly. I no longer read ghost stories or watch horror films and equally I do not seek out dark places or reptile houses. None of these things have purchase upon my psyche or even hold any interest anymore. Those scaly beasts have retreated from the world. For me, the shadows are not inhabited by the spectral and the unfathomable darkness is empty.

Bereavement entered my life and it dispelled these fears which haunted me for so long. My mother and father who used to turn out the light and leave me to sleep in my childhood room at the mercy of medieval phantasms are gone, and I have to live in the knowledge that they can no longer protect me. Once I witnessed the moment of death with my own eyes, it held no mystery for me. The demons became redundant and fled. Now they have lost their power over me, I miss them – or rather, perhaps, I miss the person I used to be – yet I am happy to live a life without supernatural agency.

Fourteenth century carvings from St Katherine’s Chapel, Limehouse

You might also like to read about

Suresh Singh’s Spitalfields

When Suresh Singh was a student at City & East London College in 1979, he was given a project for General Studies O Level to record his neighbourhood. So he set out with his camera from his home at 38 Princelet St and took these photographs of the streets of Spitalfields. They are published here for the first time today and are now in the collection at Bishopsgate Insitute.

Suresh will be in conversation with Stefan Dickers talking about his book A MODEST LIVING, MEMOIRS OF A COCKNEY SIKH at the Write Idea Festival at the Whitechapel Idea Store on Saturday November 17th at 1pm. Click here to book a free ticket

Christ Church from Wilkes St

Spitalfields Market seen from Christ Church

Looking towards the City from the rooftop of a Hanbury St factory

Children playing cricket in Puma Court

Mr Sova, proprietor of Sova Fabrics on Brick Lane

Brick Lane

Shed on Brick Lane

Shoe shop on Cheshire St

Cheshire St

Stamp and coin dealer in Cheshire St

Boy carrying home the shopping on Brick Lane

Shops on Hanbury St

Truman Brewery seen from Grimbsy St

Woman on Brick Lane

Her shoes

Down and out on the steps of the Rectory, Christ Church

Homeless men sitting outside Christ Church – this area has recently been fenced off

In Fashion St

Naz Cinema, Brick Lane

Family walking from Shoreditch Station into Brick Lane

Clifton Sweetmart, Brick Lane

Former Central Foundation School for Girls, Spital Sq, now Galvin restaurant

Inside the former Central Foundation School for Girls, Spital Sq

Abandoned books at Central Foundation School for Girls

There was a constant police presence on Brick Lane due to the race riots

Crowds leaving the mosque on Brick Lane

Sign in Fournier St

Sign in Fournier St

Christ Church prior to restoration, without balconies

Christ Church from the roofs of Hanbury St

Photographs copyright © Suresh Singh

Click here to order a signed copy of A MODEST LIVING for £20

Luke Clennell’s Dance Of Death

More than fifteen years have passed since my father died at this time of year and thoughts of mortality always enter my mind as the nights begin to draw in, as I prepare to face the spiritual challenge of another long dark winter ahead. So Luke Clennell’s splendid DANCE OF DEATH engravings inspired by Hans Holbein suit my mordant sensibility at this season.

First published in 1825 as the work of ‘Mr Bewick’, they have recently been identified for me as the work of Thomas Bewick’s apprentice Luke Clennell by historian Dr Ruth Richardson.

The Desolation

The Queen

The Pope

The Pope

The Cardinal

The Elector

The Canon

The Canoness

The Priest

The Mendicant Friar

The Councillor or Magistrate

The Councillor or Magistrate

The Astrologer

The Physician

The Merchant

The Wreck

The Swiss Soldier

The Charioteer or Waggoner

The Porter

The Porter

The Fool

The Miser

The Miser

The Gamesters

The Gamesters

The Drunkards

The Beggar

The Thief

The Newly Married Pair

The Husband

The Wife

The Child

The Old Man

The Old Woman

You may also like to take a look at

Luke Clennell’s London Melodies

Luke Clennell’s Cries of London

Piggott Bros & Co Of Bishopsgate

Before banks and financial industries took over, Bishopsgate was filled with noble trades like J W Stutter Ltd, Cutlers, James Ince & Sons, Umbrella Makers and Piggott Bros, Tent Makers – whose wares are illustrated below, selected from an eighteen-eighties catalogue held in the Bishopsgate Institute. If this should whet your appetite for hiring a marquee, Piggotts are still in business, operating these days from a factory in Whitham.

Gentlemen, I have much pleasure in bearing testimony to the satisfaction given to my family and friends by the manner in which you carried out your contract, and also to the obliging manner with which your employees carried out their duties and our wishes. Considering the gale during the week in which the ball room was erected, the workmanship was most creditable to all concerned. Your &c, B Proctor (Glengariffe, Nightingale Lane, SW)

The Round Tent – 30ft circumference, 10 shillings for one day

The Square Tent – 6ft by 6ft, ten shillings for one day

The Bathing Tent – 6ft across with a socketed pole, seven shillings for one day

The Bell Tent – for one day six shillings & eightpence

The Gipsy Tent – 9ft by 7ft, six shillings and eightpence for one day

The Boating or Canoeing Tent – 9ft by 7ft, six shillings and eightpence for one day

The Mildmay Tent –18ft by 9ft with lining, bedroom partition and awning, forty shillings for one day

Tarpaulins – 24ft by 18ft, two shillings and sixpence per week

Rick Cloth – 12 by 10 yards for 40 loads, two shillings and fivepence for a fortnight

The Banqueting Marquee

The Marquee fitted for the Church or Mission

Wimbledon Camp – The Wimbledon Prize Meeting of the National Rifle Association

The Royal Agricultural Show at Bristol – Dear Sirs, I have much pleasure in testifying to the excellence of the temporary buildings erected by you for our Tottenham, Edmonton and Enfield Industrial Exhibition, held in October last. The light and ventilation were good, and the buildings warm and waterproof, and well adapted for the purpose. Yours Truly, J Tanner, Architect (24 Finsbury Circus)

The Temporary Ball Room – Dear Sirs, Your Ball Room gave me every satisfaction, and I should have great pleasure in recommending you, should you ever care to apply to me. Yours faithfully A. Cantor (Trewsbury, Cirencester)

The Marquee for Wedding, Ball or Evening Party – In sending you my cheque for the contract price for the ballroom, I think is only due to state to you that the temporary room was a great success and my guests one and all expressed great admiration for the excellence of the arrangements and the perfection of the dance floor. It is only fair that I should state at the same time that your men carried out the arrangements well and with promptitude and in a quiet and orderly way, and I am quite satisfied with all they did. Yours faithfully, E Canes Mason (Reigate, Surrey)

The Marquee for Laying a Foundation Stone

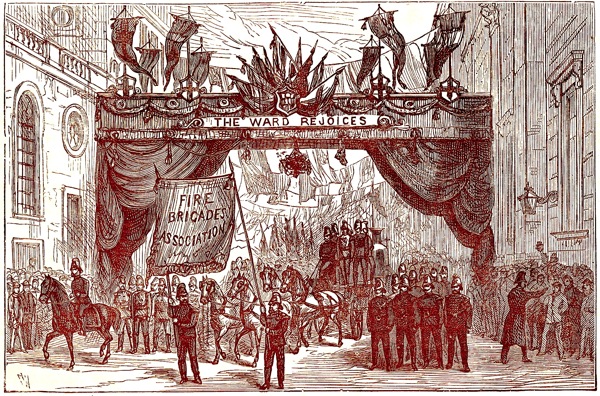

Lord Mayor’s Day, 1881

Lord Mayor’s Day, 1881 Lothbury

Piggott’s Orchestra

Piggots of Bishopsgate in the nineteenth century

Piggots of Bishopsgate in the twentith century

Images courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to read these other stories about Bishopsgate

At James Ince & Sons, Umbrella Makers

Charles Goss’ Bishopsgate Photographs

The Bread, Cake & Biscuit Walk

This biscuit was sent home in the mail during World War I

As regular readers will already know, I have a passion for all the good things that come from the bakery. So I decided to take advantage of the fine afternoon yesterday to take a walk through the City of London in search of some historic bakery products to feed my obsession, and thereby extend my appreciation of the poetry and significance of this sometimes undervalued area of human endeavour.

Leaving Spitalfields, I turned left and walked straight down Bishopsgate to the river, passing Pudding Lane where the Fire of London started at the King’s Bakery, reminding me that a bakery was instrumental in the very creation of the City we know today.

My destination was the noble church of St Magnus the Martyr, which boasts London’s stalest loaves of bread. Stored upon high shelves beyond the reach of vermin, beside the West door, these loaves were once placed here each Saturday for the sustenance of the poor and distributed after the service on Sunday morning. Although in the forgiving gloom of the porch it is not immediately apparent, these particular specimens have been there so many years they are now mere emblems of this bygone charitable endeavour. Surpassing any conceivable shelf life, these crusty bloomers are consumed by mould and covered with a thick layer of dust – indigestible in reality, they are metaphors of God’s bounty that would cause any shortsighted, light-fingered passing hobo to gag.

Close by in this appealingly shadowy incense-filled Wren church which was once upon the approach to London Bridge, are the tall black boards tabulating the donors who gave their legacies for bread throughout the centuries, commencing in 1674 with Owen Waller. If you are a connoisseur of the melancholy and the forgotten, this a good place to come on a mid-week afternoon to linger and admire the shrine of St Magnus with his fearsome horned helmet and fully rigged model sailing ship – once you have inspected the bread, of course.

I walked West along the river until I came to St Bride’s Church off Fleet St, as the next destination on my bakery products tour. Another Wren church, this possesses a tiered spire that became the inspiration for the universally familiar wedding cake design in the eighteenth century, after Fleet St baker William Rich created a three-tiered cake based upon the great architect’s design, for his daughter’s marriage. Dedicated today to printers and those who work in the former print trades, this is a church of manifold wonders including the pavement of Roman London in the crypt, an iron anti-resurrectionist coffin of 1820 – and most touching of all, an altar dedicated to journalists killed recently whilst pursuing their work in dangerous places around the globe.

From here, I walked up to St John’s Gate where a biscuit is preserved that was sent home from the trenches in World War I by Henry Charles Barefield. Surrounded by the priceless treasures of the Knights of St John magnificently displayed in the new museum, this old dry biscuit has become an object of universal fascination both for its longevity and its ability to survive the rigours of the mail. Even the Queen wanted to know why the owner had sent his biscuit home in the post, when she came to open the museum. But no-one knows for sure, and this enigma is the source of the power of this surreal biscuit.

Pamela Willis, curator of the collection, speculates it was a comment on the quality of the rations – “Our biscuits are so hard we can send them home in the mail!” Yet while I credit Pamela’s notion, I find the biscuit both humorous and defiant, and I have my own theory of a different nuance. In the midst of the carnage of the Somme, Henry Barefield was lost for words – so he sent a biscuit home in the mail to prove he was still alive and had not lost his sense of humour either.

We do not know if he sent it to his mother or his wife, but I think we can be assured that it was an emotional moment for Mrs Barefield when the biscuit came through her letterbox – to my mind, this an heroic biscuit, a triumphant symbol of the human spirit, that manifests the comfort of modest necessity in the face of the horror of war.

I had a memorable afternoon filled with thoughts of bread, cake and biscuits, and their potential meanings and histories which span all areas of human experience. And unsurprisingly, as I came back through Spitalfields, I found that my walk had left me more than a little hungry. After several hours contemplating baked goods, it was only natural that I should seek out a cake for my tea, and in St John Bread & Wine, to my delight, there was one fresh Eccles Cake left on the plate waiting for me to carry it away.

Loaves of bread at St Magnus the Martyr

Is this London’s stalest loaf?

The spire of Wren’s church of St Bride’s which was the inspiration for the tiered design of the wedding cake first baked by Fleet St baker William Rich in the eighteenth century

The biscuit in the museum in Clerkenwell

The inscrutable Henry Charles Barefield of Tunbridge Wells who sent his biscuit home in the mail during World War I

The freshly baked Eccles Cake that I ate for my tea

You may like to read these other bakery related stories

Lyndie Wright, Puppeteer

As a child, I was spellbound by the magic of puppets and it is an enchantment that has never lost its allure, so I was entranced to visit The Little Angel Theatre in Islington. All these years, I knew it was there – sequestered in a hidden square beyond the Green and best approached through a narrow alley overgrown with creepers like a secret cave.

Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I were welcomed by Lyndie Wright who co-founded the theatre in 1961 with her husband John in the shell of an abandoned Temperance Chapel. “We bought the theatre for seven hundred and fifty pounds,” she admitted cheerfully, letting us in through the side door,“but we didn’t realise we had bought the workshop and cottage as well.”

More than half a century later, Lyndie still lives in the tiny cottage and we discovered her carving a marionette in the beautiful old workshop. “People travel for hours to get to work, but I just have to walk across the yard,” she exclaimed over her shoulder, absorbed in concentration upon the mysterious process of conjuring a puppet into life. “Carving a marionette is like making a sculpture,” she explained as she worked upon the leg of an indeterminate figure, “each piece has to be a sculpture in its own right and then it all adds up to a bigger sculpture.” In spite of its lack of features, the figure already possessed a presence of its own and as Lyndie turned and fondled it, scrutinising every part like puzzled doctor with a silent patient, there was a curious interaction taking place, as if she were waiting for it to speak.

“I made puppets as a child,” she revealed by way of explanation, when she noticed me observing her fascination. Growing up and going to art school in South Africa, Lyndie applied for a job with John Wright who was already an established puppet master, only to be disappointed that nothing was available. “But then I got a telegram,” she added, “and it was off on an eight month tour including Zimbabwe.”

After the tour, Lyndie came to Britain continue her studies at Central School of Art and John was seeking a location to create a puppet theatre in London. “The chapel had no roof on it and we had to approach the Temperance Society to buy it,” Lyndie recalled, “We did everything ourselves at the beginning, even laying the floorboards and scraping the walls.” Constructed upon a corner of a disused graveyard, they discovered human remains while excavating the chapel to create raked seating as part of the transformation into a theatre with a fly tower and bridge for operating the marionettes. Today, the dignified old frontage stands proudly and the auditorium retains a sense of a sacred space, with attentive children in rows replacing the holy teetotallers of a former age.

“I had intended to return to South Africa, but I had fallen in love with John so there was no going back,” Lyndie confided fondly, “in those days, we sold the tickets, worked the puppets, performed the shows, and then rushed round and made the coffee in the interval – there were just five of us.” At first it was called The Little Angel Marionette Theatre, emphasising the string puppets which were the focus of the repertoire but, as the medium has evolved and performers are now commonly visible to the audience, it became simply The Little Angel Theatre. Yet Lyndie retains a special affection for the marionettes, as the oldest, most-mysterious form of puppetry in which the operators are hidden and a certain magic prevails, lending itself naturally to the telling of stories from mythology and fairytales.

John Wright died in 1991 but the group of five that started with him in Islington in 1961 were collectively responsible for the growth and development in the art of puppetry that has flourished in this country in recent decades, centred upon The Little Angel Theatre. Generations of puppeteers started here and return constantly bringing new ideas, and generations of children who first discovered the wonder of the puppet theatre at The Little Angel come back to share it with their own children.

“The less you show the audience, the more they have to imagine and the more they get out of it,” Lyndie said to me, as we stood together upon the bridge where the puppeteers control the marionettes, high in the fly tower. The theatre was dark and the stage was empty and the flies were hung with scenery ready to descend and the puppets were waiting to spring into life. It was an exciting world of infinite imaginative possibility and I could understand how you might happily spend your life in thrall to it, as Lyndie has done.

Old cue scripts, still up in the flies from productions long ago

Larry, the theatrical cat

Lyndie Wright

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Visit The Little Angel Theatre website for details of current productions