Terry Bay, Boxer, Compositor & Cab Driver

Terry aged four sitting on a cow named Tom

When he was evacuated from Bethnal Green at four years old, Terry Bay rode a cow through an orchard in Cambridgeshire but these days he rides a taxi around the London streets. In between these peregrinations – each delighting him with their ever-changing perspectives – Terry became a boxer and a compositor, exercising the breadth of his talents by adopting new professions to suit the varying demands of his life. Yet a pair of boxing gloves hangs from the rear-view mirror of Terry’s cab as an indicator of his true passion and, if any passenger should ask – as they often do – Terry brings out an envelope of boxing pictures that he always carries, eager to share his reminiscences with any fellow enthusiast.

I visited Terry in Barkingside where lives today, but I discovered his was a story of Bethnal Green and, in the hallway of his comfortable flat, he has an extraordinary gallery of sepia portraits of members of his and his wife’s families who all lived in Bethnal Green through many generations.

You would not automatically characterise Terry as a fighter, such is his gentle and self-effacing nature. Though when he told me his story and revealed that his father died when Terry was twelve, just before he started boxing, I understood how it became necessary to find the courage to stand up for himself. In fact, Terry discovered he was blessed with a natural talent as a boxer, yet although he won most of his fights he never became a champion. Instead, Terry shared an enduring camaraderie with his fellow boxers, benefiting from a wealth of friendships that has sustained him through the years and which he still enjoys today.

“If anybody asks, I say I come from Bethnal Green. I was born in Cranberry St off Vallance Rd in 1937 – but a bomb fell there in 1940 and we moved out, first to Corfield St and then to Middleton St where I lived until was twenty-six. But, in 1941, at four years old I was evacuated to Chatteris with my brother Albert and my sister Rita. My mother Connie – she was born in Russia Lane – she wouldn’t let us be separated. My father Bill – he was a fireman during the war – he came from Menotti St, and he died when I was twelve. He had TB and didn’t go for treatment. He worked in the Docks before the war and that’s how my brother got into the Docks. Later, me and my brother and my sister, were put under observation for TB because we were so skinny. We had to go the children’s clinic in Underwood Rd and they gave us spoonfuls of cod-liver oil which I hated.

The man we were sent to in Chatteris was a farmer, and he had an orchard out the back where he kept the chickens and pigs. He cleared out the chicken house and we stayed there, and my mum came to visit too. She used to wring the chicken’s necks and pluck them, and shoot the pigs with a pig gun. She did everything, she worked in bottle factory and she was a cleaner, and she lived for her children. Later, my cousins came down to join us and we all stayed in a cottage, and then my mum and dad came to visit us – and when the war was over, they came down and took us back to Bethnal Green.

I went to infant school in Teesdale St and then at eleven years old I went to the Mansford St where they had an after-school boxing club. There were all these boys standing in a circle and there was one kid who looked like a boxer. He was deciding who to box and – as I was thin and I didn’t look as if I could box – he picked me. It went a couple of rounds and he was supposed to be boxing me, but I was boxing his head off and he realised I had a natural talent – and he got the hump. So then I went off to the Mansford Boxing Club with Terry Staines and Georgie Whaiter and I had a couple of bouts there. The Repton Boxing Club was going strong and they poached Terry and Georgie, so I tagged along and became a Repton boy. They took me to the London Federation of Boys’ Clubs Competition and I won my first fight but got beaten in the semi-final. That was the story of my life, there was always somebody better than me! I boxed seventeen times as a junior and lost five. Then I gradually fell away from it, I was a teenager and I got distracted.

I left school and did a six year apprenticeship and became a compositor and got married and wanted to better myself and I went to work in Fleet St. At first, I worked for the Evening News where I got a holiday frame, covering for people on leave, but then I applied for a permanent job the next year and they kept me on. And I thought I was a millionaire, I was getting fifteen pounds before but at the Evening News I got thirty-seven pounds a week! This was in 1969 and I was thirty-two. You worked with hot metal and you had deadlines to meet. Firey Fred was the head printer and he used to be always on your back when you were working on a page, ‘Hurry up! Quick as you can, mates.’ There was a metal frame for the page and stories came in hot metal, and you had a graph of how it was supposed to be. The journalists came and told you where they’d like their stories and, if it was too long, they’d cut it down. Finally, you had to plane the plate down and that’s when I got my finger permanently bent. There was two of us working on a single page. One worked at the top and the one that worked at the bottom was the assistant. He was planing the finished page down to make it smooth and we were in a hurry because Firey Fred was making us sweat. It used to be a bit crazy. Then it’d all go quiet – and you’d go off and have breakfast or a beer until the next edition.

My wife and I moved into a flat in Cressy Mansions in Stepney when we got married but six months after our son Fraser was born in 1970 we moved out to a house in Chigwell. Eventually, after twelve years at the News Chronicle, I was made redundant when it closed in 1981. Then I did ten years at the Daily Mirror until computers came in and I was made redundant again, after Robert Maxwell took it over. I worked at Tower Typography in Holywell Lane, Shoreditch, doing general typesetting for a while, but I didn’t like it after the excitement of the newspapers. When I finally left printing, I bought a pub, The Dolphin on Redchurch St, but that didn’t suit either, the life of a publican. That’s when I became a cab driver, and that’s what I’ve done ever since, for the past twenty-four years.

I was never a famous boxer. My father loved boxing, he would have liked what I did but he died before I started. And although my mother never liked me doing it, I made a lot of friends and I had a fun-filled time with my pals. I was brought up in a rough area and people got into trouble. I was in a car once with some friends, and the police stopped us and found wax impressions and tools for making keys in the boot. They took us back to the station and I was remanded in Brixton for two weeks, even though I was never a villain or a thief.

The only thing I’ve done that I’m really proud of is my boxing life. Once I overheard the headmaster at my school talking to a class and he said, ‘I watched Terry Bay sparring in the playground and he’s very good.’ I didn’t know I was good. And for him to have said that meant everything to me.

I didn’t try to be a tough guy but you had to take care of yourself. I wasn’t brave, I was scared of being scared.”

Terry at the Repton Boxing Club.

Terry is on the far right of this picture of the Mansford St School Boxing team 1951.

Terry as a schoolboy.

Terry and his friend Bobby in Petticoat Lane, 1954.

Terry enjoys a drink with his mates at the Westminster Arms on the corner of Old Bethnal Green Rd.

Terry with pals outside departures at London Airport on the way to a holiday in Jersey.

At Strakers & Sons, Hackney Wick, where Terry was apprenticed as a compositor in 1956. Terry can be seen in the distance on the right in a white shirt.

Mr Souter, the press man, and Nobby, the overseer. Terry is on the extreme left.

Terry & Eileen at their marriage in 1969.

Terry with his good friend Terry Spinks, the famous boxer who won a gold medal in the 1956 Olympics and died this year, also shown as a younger man in the inset.

Terry Bay has a pair of boxing gloves hanging in his cab and always carries his boxing photos in an envelope in case he meets a fellow boxing enthusiast.

You may like to read these boxing stories

Sylvester Mittee, Welterweight Champion

Paul Anthony Gardner’s East End

Over the last quarter century, Photographer Paul Anthony Gardner (not the famous paper bag seller of the same name) has been recording the diverse architectural heritage of the East End. In the intervening years, some buildings have been cherished while others have been neglected and too many have been destroyed, but thanks to Paul we have these atmospheric photographs as evidence.

Timber Merchant, Whitechapel, 1998

Path under Railway Bridge, Limehouse 2008

Christ Church, Spitalfields 1996

Former Dispensary, Stratford 2009

Abbey Mills Pumping Station, Stratford 1997

East India Dock Rd, Limehouse 2008

German Lutheran Church, Alie St, Aldgate 1996

Baptist Chapel, Grove Rd, Bow 1997

House Mill, Three Mills Island, Bromley by Bow 1997

Lift Bridge, Shadwell Basin 2000

Princelet St Synagogue, Spitalfields 1996

Warehouses at the Bishopsgate Goodsyard, 1999

Council Chamber, Shoreditch Town Hall 1998

Puma Court, Spitalfields 1998

St Botolph’s Hall, Aldgate, 1996

Shoreditch Town Hall, 1996

Princelet St Synagogue, Spitalfields 1996

London Tramways Shed, Shoreditch 1998

Trinity Green Almshouses, Whitechapel, 1998

Hydraulic Pumping Station, Wapping, 1996

Undertakers. Limehouse, 2007

Wilton’s Music Hall, Cable St, 1996

Photographs copyright © Paul Anthony Gardner

You may also like to take a look at

Nigel Taylor, Tower Bell Production Manager

Nigel Taylor worked at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry for forty years, from 1976 until it closed in 2017, managing all aspects of making, casting and tuning bells for the last twenty years.

In this interview, Nigel explains why the foundry closed and twenty-five jobs were lost. Yet as advisor to UK Historic Building Preservation Trust & Factum Arte‘s scheme to reopen the foundry, re-equipped for twenty-first century, he is confident it can have a viable and sustainable future.

Below you can also read a statement by Dr Tristram Hunt, Director of the Victoria & Albert Museum who this week declared his support for scheme to re-open the foundry.

If you have not yet submitted your objection to the proposal to redevelop the Whitechapel Bell Foundry into a bell-themed boutique hotel, instructions follow beneath.

“I do not want to see all the things that England once held dear just die, especially the crafts and industries that we once had” – Nigel Taylor

Perhaps no-one was better placed to bear to witness to the tale of the closure of the historic Whitechapel Bell Foundry – the world’s most famous foundry – than Nigel Taylor, who worked there for forty years and was the senior foundry man. At the time, we understood that the closure of the foundry was inevitable due to the decline in demand for church bells, but Nigel Taylor has a different story to tell.

His is a sobering account which reveals that the shutting of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry was avoidable. Nigel asserts that it was a deliberate act by the bell founders who chose to sell up and sacrifice twenty-five jobs, rather than take action to modernise and ensure the survival of Britain’s oldest manufacturing business. Yet Nigel’s testimony also contains hope by asserting his belief that the foundry can have a viable future as a living foundry, rather than be ignominiously reduced to a bell-themed boutique hotel as has been proposed.

Nigel has been consumed by the culture of bells since early childhood and he is a passionate spokesman for those who make bells, those who ring bells, and all those who love bells.

“I am a Londoner, born in Hampstead. When I was a boy, my grandparents lived in Warwick, so as a small child I often heard the eight bells of St Nicholas. I was fascinated by the sound. I heard the sound of the bells of St Mary’s in Warwick as well. When I was five years old, I identified that they had ten bells not eight and they were a lower pitch. So my passion for bells was already there.

When I was six, we moved to Oxfordshire and the bells at Chipping Norton had not been rung for many years but they were rehung by Taylors of Loughborough. A friend of mine said, ‘They’re trying the bells out tonight, let’s go and listen.’ They told us, ‘You can’t learn to ring until you’re eleven.’ So when we were eleven, we went along to ring and my friend is still ringing the bells in that tower. Once I started to ring bells, I never looked back.

When I left school, I wrote to the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and asked, ‘Do you have any vacancies?’ I had an interview with Douglas Hughes – father of Alan Hughes the last bell founder – and he said, ‘We’ll start you off in the moulding shop.’ I had no experience. There were no college course in loam-moulding or anything like that. You could do an apprenticeship in an iron foundry in loam-moulding and some of the bell founders did that after they left school. But I learnt everything I know at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry.

My feelings about it were quite mixed when I arrived in 1976. I had to get used to a lot of bad language which was not tolerated at school in those days. There were an interesting variety of characters, some ringers and some not. I started off making up the loam which is a mixture of sand, clay, horse manure and all the rest of it. I was the one that introduced Jeyes Fluid into the mix, just to kill off some of the bugs. Then I made moulding bricks, using loam, and dried them in the oven. They acted as packing between the moulding gauge or template and the cast iron flask, filling the space between them. Then I started making cores and, after the head moulder retired in 2003, I got to do the inscriptions. I did the lot and I was running the entire foundry production by that stage as Tower Bell Production Manager, managing the making of the bells, the casting of the bells and the tuning of the bells.

I really liked doing the inscriptions. To begin with I made white metal copies of the inscriptions on old bells to transfer to the new ones when they were recast. Later, I made casts of inscriptions in resin and stamped them into the new mould while it was still damp. We also had various letter sets in different sizes, decorative lettering and stock friezes. We often put friezes on bells, at least one if not two or three. It was a very satisfying job, because a bell is likely to last for centuries. I used to put headphones on and listen to some music while I was working and I thought, ‘This is going to outlast me.’ I have lost count of how many bells I have made. I could count how many bells I have tuned because I have kept my notebooks, so I could go through and count them. It must be thousands.

Just before the Whitechapel Bell Foundry shut, we had an order for some bells from Thailand which required a special stamp. So rather than make it the old fashioned way, I went to a 3D print shop in Canary Wharf and they printed the design for one fifth of the cost of how we did it before. It was a highly significant moment, three months before the foundry closed down.

I want to see the Whitechapel Bell Foundry re-opened as a foundry. I believe it would be economically viable. The previous business could have been economically viable with the right kind of marketing and the right kind of management.

I would like to see local people involved in foundry work, because there are no other buildings in this locality which are suitable for this purpose. I would like to see apprenticeships and training in all aspects of casting – pattern-making, moulding, fettling, machining, polishing and tuning. There are a whole range of different skills to be taught and there would be employment for those people.

I would like to take an advisory role with regard to how best to make use of the building and set up the various workshops, and especially in the design and making of patterns for bells. The previous furnaces were oil-fired but my preference is for electric which would lower the emissions considerably.

I am in favour of modernising the foundry for the twenty-first century. In the last few years, it became increasingly difficult to obtain traditional materials. Quarries which supplied sand were becoming landfill sites, so we struggled to find sand that was suitable to produce loam. If you discard that system and use resin-bonded sand instead, the strength of the mould is no longer reliant upon which quarry the sand comes from and you can have a much higher success rate with your castings. It is cleaner too. We used to have clouds of loam dust floating around everywhere – it was a dirty job.

In the past, patterns were made of wood but now we can design the profile of a bell and digitally print the pattern in high-density polypropylene, which can be reused, making the process far cheaper. You can do it in one day instead of over a matter of weeks and you can make dozens of bells with one pattern that way. It is a huge difference.

There was a dip in sales around 2012/3 as a result of government spending cuts. I think bell founders Alan & Kathryn Hughes misinterpreted this as a terminal decline in bell founding, so when the market picked up they were not ready for it. It was obvious to me that they needed a good marketing strategy, but I saw them carry on with their old policy regardless and the Whitechapel Bell Foundry began to decline rapidly while Britain’s other bell foundry, Taylors of Loughborough, picked up the lion’s share of the work due to aggressive marketing. The Hughes incurred debts in the region of £450,000 but they were thrown a lifeline by the offer of purchasing the building. By then, the building was worth money and the business was worth nothing. So they took the lifeline and foundry closed in 2017.

In my estimation, Alan & Kathryn Hughes ran out of puff. They had two daughters who were not interested in the business. After three generations of ownership, it seemed the Hughes could only see it as a family business, so if no-one in the family was going to run it that was the end of business. That was certainly how it appeared to us, the staff, and it became apparent in the way the Hughes allowed the business to collapse.

I knew the Whitechapel Bell Foundry needed to put in more competitive quotes and carry out free inspections for prospective jobs. We were the only firm in the business that charged for quotations. It cost us a lot of work. We needed to introduce proper marketing, concentrate on their products and skilled staff – not the fact that it was a family business which was the oldest manufacturing company in England. Customers cared more about whether we could do a good job and how much it was going to cost. The Hughes might have introduced some new directors to bring fresh ideas but their notion of a family business prevented that.

So they did none of these things and twenty-five jobs were destroyed. I think the Hughes tried to block out their responsibility to their employees. I saw how Alan Hughes allowed circumstances to decline until they passed a point of no return. He once said to me, after he had announced that the foundry was going to close and we were all going to lose our jobs, he said ‘It’ll be quite interesting to dismantle it.’ It suggested he had formed a barrier to the emotions that must be inherent in anyone whose is going to close a business that has been in existence for over four hundred years.

In my opinion, he closure was avoidable. With the right strategy, I believe the foundry could have survived, or they could have sold the building and the business when it was a going concern and walked away with a nice amount of money in the bank. But their actions revealed they could only contemplate it as a family business. At present, there is a lot of work about. The bell market and the art foundry market are both very buoyant and I believe the new proposal is perfectly viable.

I am District Master of the Essex Association of Bell Ringers, and I still ring bells at least three nights a week and quite a lot at weekends. I am a traditionalist, I do not want to see all the things that England once held dear just die, especially the crafts and industries that we once had.”

STATEMENT OF SUPPORT BY THE DIRECTOR OF VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM

“The re-established Whitechapel Bell Foundry would add significantly to the creative offer in East London. As the V&A East establishes a substantial presence at Stratford and the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and develops particular links with the adjacent boroughs, we would welcome the opportunity to promote the Whitechapel-based art and bell foundry. Combining traditional skills with innovative technology and the offer of apprenticeship and further training in this specialized field will enhance the interpretation of the V&A’s important collection of works of art in bronze. Continuing the centuries-old tradition of bell founding in London with its global outreach will enrich the cultural presence and attract national, regional and international interest.”

Dr Tristram Hunt

You can help save the Whitechapel Bell Foundry as a living foundry by submitting an objection to the boutique hotel proposal to Tower Hamlets council. Please take a moment this weekend to write your letter of objection. The more objections we can lodge the better, so please spread the word to your family and friends.

HOW TO OBJECT EFFECTIVELY

Use your own words and add your own personal reasons for opposing the development. Any letters which simply duplicate the same wording will count only as one objection.

1. Quote the application reference: PA/19/00008/A1

2. Give your full name and postal address. You do not need to be a resident of Tower Hamlets or of the United Kingdom to register a comment but unless you give your postal address your objection will be discounted.

3. Be sure to state clearly that you are OBJECTING to Raycliff Capital’s application.

4. Point out the ‘OPTIMUM VIABLE USE’ for the Whitechapel Bell Foundry is as a foundry not a boutique hotel.

5. Emphasise that you want it to continue as a foundry and there is a viable proposal to deliver this.

6. Request the council refuse Raycliff Capital’s application for change of use from foundry to hotel.

WHERE TO SEND YOUR OBJECTION

You can write an email to

planningandbuilding@towerhamlets.gov.uk

or

you can post your objection direct on the website by following this link to Planning and entering the application reference PA/19/00008/A1

or

you can send a letter to

Town Planning, Town Hall, Mulberry Place, 5 Clove Crescent, London, E14 2BG

You may also like to read about

Hope for The Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Royal Jubilee Bells At Garlickhythe

The Most Famous Bells in the World

A Visit To Great Tom At St Paul’s

A Petition to Save the Bell Foundry

Doreen Fletcher’s Lost Time

Fiona Atkins, gallerist at Townhouse Spitalfields, will be giving a lecture about Doreen Fletcher’s painting at the Nunnery Gallery on Wednesday 20th February as part of Doreen Fletcher’s Retrospective exhibition which runs until 24th March. In advance of her lecture, Fiona explores Doreen’s work as a response to the changing East End in the eighties. Click here to book

Mile End Park at Twilight, 1987

Many people in the East End in the eighties probably did not recognise the significance of the changes that were taking place. The development of Canary Wharf, sitting in detached isolation, appeared to have nothing to do with them and preoccupied by the day-to-day, they carried on as usual. When Doreen Fletcher arrived in 1982, she instantly warmed to the sense of community evident in the corner shops, and cafes – to the familiarity of the terraced streets with the small houses that reminded her of home.

Yet as an outsider, she could see what the locals could not see because it was too familiar: that those same shops, pubs and cafes were remnants of an earlier community that had been slowly disappearing since the end of the Second World War, and they were not going to survive much longer.

So Doreen began to paint: she was not documenting architecture or history, she was painting the everyday lives of people living in an ordinary community. Over the next twenty years, she created what we can now see are an extraordinary group of paintings of an East End that has all but disappeared, and which will themselves become a part of the cultural memory of the East End as we come to realise what has been lost.

People feature rarely in her paintings, although they are there. It is the places that were the focus of the community that caught her attention. She did not use many of the shops and cafes herself and they are viewed with the eye of an outsider, a status which facilitated a clear vision. Yet, although people are largely absent from her paintings, there is an underlying warmth, revealing life going on behind the scenes, often conveyed in the small details: a light on in a room, a discarded beer can in the gutter and the graffiti. The two women chatting at the bus stop, in the painting of the same name, are unusual but they are barely noticeable, screened by the barrier of the shelter.

John Cooper, artist, teacher and founder of the East London Group, wrote ‘You can spoil the humanity of a picture if you put figures in,’ and Doreen’s humanity shines through, despite the lack of figures in her work. Mile End Park at Twilight was an early East End painting of Doreen’s and her choice to paint it at dusk immediately imbues the scene with a warm glow.

The light shining from the windows, including from the illuminated sign, contradicts the message of the boarded-up terrace of houses: there is clearly still life in these buildings. Condemned House was painted in the same year and enlarges on the theme. The house appears to be inhabited, with no suggestion that it has been abandoned and the curtains reveal an owner who was once proud of their home. The tree, apparently a rare one, is painted with colourful vibrancy, yet the broken railings hint at the fate of both house and tree.

Doreen paints with feeling and her style is well ordered and harmonious with a strong sense of colour. The flat clarity of her scenes occasionally lends her work the air of eighteenth- or nineteenth-century folk art, as for example Mile End Park with Church, which could almost be an eighteenth-century view painted with the clear vision of a young Gainsborough. It is a style that suits her theme in depicting a world that is orderly and peaceful, where derelict buildings convey a sense of the past rather than urban decay and there is no suggestion of aggression or violence. It accords with our perception of the post-war East End as a time of close-knit communities when the world was perhaps a simpler place – a lost time.

Bus Stop, Mile End 1983

The Condemned House, Poplar 1985

Mile End Park With Church, 1988

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF DOREEN FLETCHER’S BOOK FOR £20

Last Chance For Tadmans

I was dismayed to learn that permission had been granted for demolition of this fine Georgian corner building at 116 Jubilee St which has been a popular landmark for almost two centuries. Yet research this week by members of the East End Preservation Society has revealed that – due to a technicality – a decision has not, in fact, been made and it is still possible to lodge objections which must be taken into account by the council. Read the Society’s letter below accompanied by instructions explaining how to write your own objection. There is no time to waste because this is the last chance to save Tadmans in Stepney.

Jubilee St was laid out when Commercial Rd was constructed at the beginning of the nineteenth century to bring traffic from the docks to Aldgate and this building is one of the few from the Mercers’ Estate that survived both the blitz and the post-war slum clearances. Terraces at the north end of Jubilee St give a clear idea of how the entire street once looked, before the cityscape was torn apart in the mid-twentieth century and inferior modern buildings replaced their dignified predecessors.

Occupying the street corner with Stepney Way, it was built as The Mercer’s Arms and records of landlords date back to 1830. It became a greengrocer after 1915 and then Tadmans the undertakers in the seventies, moving to Jubilee St from Cable St. Tadmans have overseen the safe journey of generations of East Enders from this world to the next. As well as Stepney, they have parlours in Bethnal Green and Walthamstow.

Recognising its distinctive quality, Geoffrey Fletcher drew Tadmans in Jubilee St and included it in his seminal book of neglected yet significant buildings in the capital, The London Nobody Knows in 1962. Many of those London landmarks Geoffrey Fletcher recorded in his book have been saved and there is still hope that Tadmans can be too.

The generic London spreadsheet architecture that is proposed to replace Tadmans, 116 Jubilee St, comprising luxury flats without any social or ‘affordable’ housing

The generic London spreadsheet architecture that is proposed to replace Tadmans, 116 Jubilee St, comprising luxury flats without any social or ‘affordable’ housing

LETTER OF OBJECTION BY THE EAST END PRESERVATION SOCIETY

To The Director of Planning

Tower Hamlets Council

Mulberry Place

5 Clove Crescent

E14 2BG

Dear Mr Weir

116 Jubilee Street. Refs: PA/18/01423 & PA/18/00104

We write to express our strong opposition to the demolition of No. 116 Jubilee Street. This building is the subject of the current, undecided application PA/18/01423 and the approved application PA/18/00104.

If you are accepting comments on PA/18/01423 we would like you to count this as an objection.

No. 116 Jubilee Street dates from the early nineteenth century and is a fragment of the Mercers’ estate which extended east to Jamaica Street. This building, together with the surviving group (Nos 175-93) at the north end of Jubilee Street, displays the modest but high-quality development undertaken by the Mercers in this area. Jubilee Street itself is named after Jubilee Place, a small alley which marked the Golden Jubilee of George III in 1810. It was the first street to be built north of Commercial Road.

No. 116 was clearly built as a public house and is marked on Ordinance Survey maps from the nineteenth century as such, though in recent decades it has housed a funeral directors. It is shown, together with adjoining terraced houses, on OS maps up until the sixties. This particular area largely survived the Blitz, but most of the historic housing stock was sadly demolished for new housing in the sixties and seventies. There can be no doubt that if these houses had survived they would be a cherished part of the East End townscape – as are the houses that do survive further north on Jubilee Street and elsewhere within the Borough.

During the sixties and seventies, when areas of historic housing were cleared, pubs and churches were often left standing. Unlike the churches however, most pubs nineteenth-century pubs are not listed. Furthermore, as with No. 116, they remain isolated in areas of dominated by modern estates, giving them little hope of being included within Conservation Areas. However, as corner buildings they have a particular architectural distinction, constituting important landmarks, often with curved corners. Corner pubs and were intended to give the adjoining terraces a visual ‘anchor’ and be visible from connecting streets.

No. 116 is modest but carefully designed, elegant and well preserved. It now stands alone as an evocative reminder of how attractive and well-cared for these streets were before demolition.

• The building is not and does not fall within a designated heritage asset and, in a desk-based assessment, is therefore more difficult to identify as heritage worthy of protection. However, there are general policies designed to protect buildings such as these and it is vitally important that your council employs them in instances such as this. The proposed replacement building is not commensurate with the quality of the building it proposes to replace and will therefore contravene Policy SP10 of your Core Strategy which promotes the conservation of historic buildings and promotes good new design. The proposed scheme clearly falls short of these aspirations.

• The National Planning Policy Framework states that planning authorities should require applicants to assess the impact on the significance of any affected heritage assets. This building is certainly a heritage asset and should therefore be assessed in any proposals.

• No.116 is an ideal candidate for Local (if not national) Listing. Local Listing is a tool which should be employed to protect historic buildings such as this. Unfortunately, Historic England cannot be relied upon to list worthy buildings proposed for demolition.

Your Council must protect the buildings that survived the Blitz and post-war clearance and not perpetuate a legacy of needless destruction of its historic environment.

Yours sincerely,

The East End Preservation Society

Geoffrey Fletcher’s drawing of Tadmans from The London Nobody Knows, 1962

HOW TO OBJECT TO THE DEMOLITION OF TADMANS

Read the East End Preservation Society’s letter, then use your own words and add your own personal reasons for opposing the demolition. Any letters which simply duplicate the same wording will count only as one objection.

1. Quote the application reference: PA/18/01423

2. Give your full name and postal address. You do not need to be a resident of Tower Hamlets or of the United Kingdom to register a comment but unless you give your postal address your objection will be discounted.

3. Be sure to state clearly that you are OBJECTING to the application.

4. Request the council refuse the application for the demolition of Tadmans.

WHERE TO SEND YOUR OBJECTION

You can write an email to

dr.developmentcontrol@towerhamlets.gov.uk

you can post a letter to

Town Planning, Town Hall, Mulberry Place, 5 Clove Crescent, London, E14 2BG

The symbol of the Mercers’ Company upon the wall of Tadmans, formerly The Mercers’ Arms

Catching Up With Peta Bridle

Since 2013, I have been regularly publishing Peta Bridle’s splendid drypoint etchings of London and it my pleasure to present this selection of new works, seen publicly for the first time here today

View over Mare St, from St. Augustine’s Tower, Hackney

“I visited St Augustine’s Tower recently. Although I do not like heights, it was worth the struggle up the stairs for the view from the top. A man sat begging under the bridge while people on mobiles walked past, red buses turned the corner onto Mare St and the towers of the City huddled in the distance.”

George Davis is Innocent, Salmon Lane, Limehouse

“This graffiti has survived under a railway bridge, adorned with metal signs, since the seventies. I like graffiti and street art because it manifests the human touch. George Davis was an ex-armed robber who was imprisoned in 1975 for an armed payroll robbery at the London Electric Board Offices. Graffiti proclaiming his innocence can still be found on walls and railway arches.”

The Poplar Rates Rebellion Mural, Hale St, Poplar

“This bold mural, painted in primary colours, commemorates the rates rebellion led by councillor George Lansbury in 1921, pictured on the wall in his hat and chain of office. Poplar Council refused to take rates money off their poor residents because they believed it was unjust. Thirty councillors were imprisoned for contempt of court but were released after campaigning and their names are listed on the wall.”

The Thames Pub, Deptford

“This derelict pub, once know as the Rose & Crown, sits on the corner of Thames St and Norway St, and has been painted a deep rose hue. It is surrounded by new building and a brand new supermarket across the road, so I think its days are numbered.”

Petro Lube, Silvertown

“This derelict building, once the headquarters of Petro Lube, stands on an industrial estate in Silvertown. Note the building works in the background – (a common theme in many of these etchings).”

Abandoned Caravan, Poplar

“This caravan had been abandoned at the side of a minor road near the tip. When I returned a few weeks later to take reference shots, I discovered it in pieces piled on top of a skip. Nothing stands still in London.”

Gasometer, Bow Creek, Poplar

“I spotted this Victorian gasometer while out for a walk along Bow Creek. It was already partially dismantled and, when I returned a couple of months later, it had totally disappeared.”

Abandoned Nissan, Chapman St, Shadwell

“This car is not going anywhere, but I found it made a good subject with its graffittied bonnet and crazed windscreen.”

Spur Inn Yard, off Borough High St, Southwark

“Borough High St was once lined with inns . The Spur Inn, first recorded on a map in 1542, was desrcibed by John Stow as one of the ‘fayre Innes for receipt of travellers.’ It stood the test of time, even though it ceased to be an inn in 1848. A huge wooden beam was set into the left hand wall as you enter under the high archway and, on the right, timber frames criss-crossed the brickwork. The cobbled yard was narrow yet quite beautiful. This is the view from the back of the yard looking towards Borough High St. The tarpaulin at the top hides the roof and chimney stack, prior to demolition. Spur Inn Yard was swept aside to be replaced by a new hotel which opened in 2017. All that remains is the timber set into the wall and the old stone cart tracks.”

Prints copyright © Peta Bridle

You may also like to take a look at

Daniele Lamarche’s East End

Cheshire St Doorway – “He once ran after me into the beigel shop and urged me to follow him. I had no idea what he wanted, but he led me back to my car on Bethnal Green Rd to show me that I’d left my keys in the door – he was desperately worried I would lose them. It made me chuckle after that when passers-by clutched their shoulder-bags firmly and crossed the street at the sight of him.”

Photographer Daniele Lamarche came to stay in a flat in Wentworth St for two weeks in 1981 and ended up staying on for years. Working as an international news scriptwriter for Independent Television News in Leadenhall St, Daniele first visited Brick Lane when the Indian correspondent brought her here for lunch and she was capitivated. “As you crossed Middlesex St, coming from the City of London, all the windows were smashed and things were desolate.” she recalled, yet for Daniele it was the beginning of a fascination explored through photography which continues until the present day. “I found it interesting that a lot of people would not come and visit me in East London,” she confided to me, “Because it was the first place I found in London with a sense of wonder, a sense of poetry.”

In 1982, Daniele began taking photographs in Brick Lane. It was a time of racial discord in the East End and, working for the GLC Race & Housing Action Team, Daniele employed her photography to record injuries inflicted upon victims of racial assault, the racist graffiti and the damage that was enacted upon the homes of immigrants, the broken windows and the burnt-out flats. “People actually spat at me and shouted at me in the street,” she confessed. Undeterred, Daniele became part of the Bengali community and was called upon to photograph poor living conditions as residents campaigned for better housing – with the outcome that she was also invited to record more joyful occasions too, weddings and community events.

A Californian of French/American ancestry who grew up in Argentina and was taught to ride by a Gaucho, Daniele found herself in her element working at the Spitalfields City Farm for several years where she kept dray horses and rode around the East End in a cart. An experience which afforded the unlikely observation that the lettered fascias on shops and street signs are placed high because they were originally designed to be at eye-level for those sitting in horse-drawn vehicles. Becoming embedded in Spitalfields, Daniele photographed many of the demonstrations and conflicts between Anti-Fascist and Racist groups that happened in Brick Lane, taking pictures for local and national newspapers, as well as building up a body of personal work which traces her intimate relationship with the people here, reflecting the trust and acceptance she won from those whom she met.

George, Nora & the Pigeon Cage – “East Enders who once cared for the ravens at the Tower of London, they soon took to raising racing pigeons for club meetings and competitions.”

Bethnal Green Pensioner – “A delicately-faced woman answered the door when I knocked and talked to me at length about her life, her dreams and her memories…”

Elections – “A group of Bengali women vote in 1992 – when the BNP stood in Tower Hamlets – many for the first time, following a drive made by groups including ‘Women Unite Against Racism.’ This was formed when local women found themselves to be three or four in meetings of over a hundred men and decided that, rather than be patronized as token females, they preferred to reach out to empower and support those women who might not otherwise vote.”

Eva wins the prize – “Eva came from Germany in the fifties, and grew plants and made soups out of what others might consider weeds – nettles, spinach, beet root tops – as well as sewing and embroidering all manners of pillows and textile pieces, from hop-pillows to aid sleep at night to tablecloths in the Richelieu style – and she was always game to show her wares of jams, sewing and plants at local events.”

French waiter in the docklands.

John & John – “This is John Lee, formerly of Spitalfields City Farm, now an organic dairy and pig co-operative farmer in Normandy, and ‘John’ who would often pop in to visit from Brick Lane Market and use the toilet.”

Immigration – “This refers to the moment when individuals of Asian origin in East Africa were told their colonial British passports would be no longer valid after a certain date – thus causing many to come to Britain to establish their rights to nationality, and as a result, many families camped out at the airport waiting to be met.”

Toy Museum Lascars – “a set of nineteenth century figures which represent seamen from a range of ethnicities and cultures who would have once been seen in the docklands.”

Lam at Fire – “Lam who worked for the GLC’s Race and Housing Action Team visits a family of Vietnamese heritage in 1984 in the Isle of Dogs after they were petrol bombed the night before and only saved because the granny awoke and saw smoke. Lam lived as a refugee in Hong Kong, and then in England where he was housed at first in a small village which greeted him with a gift of dog faeces through the letter box. ‘Is it the same in the USA?’ he asked me.”

Minicab – “A traditional minicab sign hovers over a resident whose front door, back door and side doors touched three different boroughs, causing him havoc and much correspondence with council tax officers.”

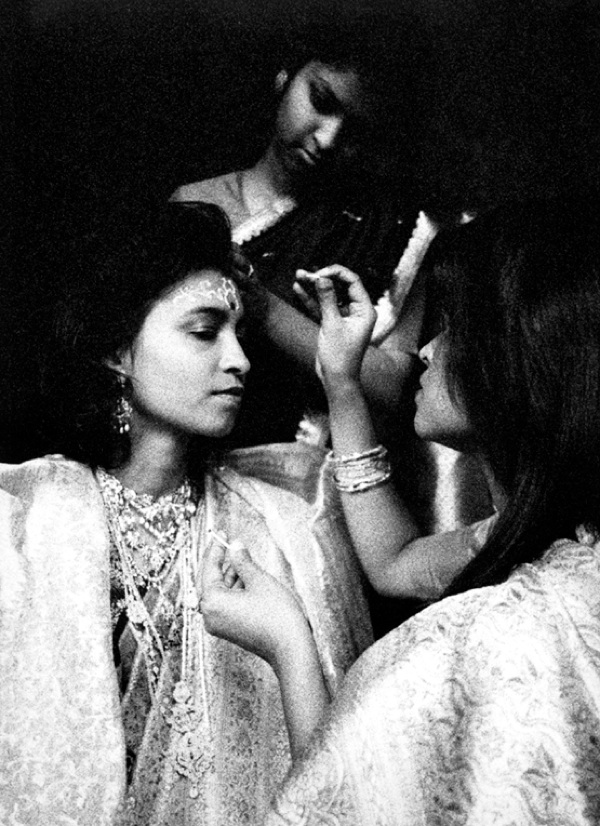

“Noore’s sister-in-law and friends help with wedding preparations, and a spot of toothpaste for intricate designs on her forehead.”

Paula, Woodcarver in her studio.

“Peter’s trades ranged from wheeling an old cart around as a rag & bone man to performing Punch & Judy puppet shows at children’s parties. Furniture and objects of interest flowed through his flat, and overflowed into the courtyard when a boat, which he’d sit in for evening cocktails, wouldn’t fit through the front door….”

Salmon Lane Horses – “A girl and her mother wait for the farrier after returning from school. Stables with horses for work and leisure dotted the streets and yards until developers picked off the remainder of the wasteland and yards where the animals were housed.”

Somali Girl – “This shows one of a group of children playing in a courtyard off Cable St where homes backed onto one another, enabling children to play within sight and ear-reach of parents indoors.”

Vietnamese Baby – “A voluntary sector advocate visits a Vietnamese family to check on their newborn’s progress. Over five hundred Vietnamese children of Chinese origin attended Saturday supplementary school classes at St Paul’s Way School in the eighties and nineties, most from Limehouse and the Isle of Dogs. Many had been housed across Britain but chose to leave the isolation of village homes, offered in a Home Office policy of dispersement, preferring the security of living in the metropolis – sometimes with thirteen family members in two rooms – thereby linking with community networks leading to jobs, further training and more fulfilling lives.”

Members of the Vietnamese Friendship Society.

Lathe, Whitechapel Bell Foundry – “Photographed in the eighties when the Bell Foundry was more a local point of interest, before it grew internationally famous.”

Brick Lane at Night – ” At a time when women were rarely seen on Brick Lane, I was once asked where my ‘friend’ was. I said the person I usually shopped with must be out and about – to which the questioner kindly patted my hand and whispered ‘they always come back…’ Some time passed before it dawned on me that many of the white women accompanying Asian men on the street were ‘working women’….”

Market Cafe Farewell – “Market traders, artists and local characters, ranging from Patrick who directed traffic from the Blackwall Tunnel and Tower Bridge to Commercial St- regardless of whether it flowed without his assistance – all squeezed into this one-room-cafe which opened in the early hours of each morning. Then it vanished one day with only a farewell note left to confirm where it had been.”

Photographs copyright © Daniele Lamarche