The Soup Kitchens Of Spitalfields

Today Philip Carstairs traces the history of Spitalfields through its soup kitchens and, if this leaves you hungry for more, he will be speaking about soup kitchens at London Metropolitan Archives at 2:30pm on Tuesday May 21st (Click here for tickets)

This feature is complemented by Stuart Freedman‘s photographs taken at the Jewish Soup Kitchen in Brune St, Spitalfields, in 1990

Jewish Soup Kitchen 1902, 17-19 Brune St

Huguenot Soup Kitchen 1797, 115 Brick Lane

You cannot write a history of Spitalfields without describing its soup kitchens, nor can you write a history of soup kitchens without discussing Spitalfields. The relationship between the two is deeply entwined and both their stories are complex and interesting. The history of these kitchens encapsulates the changes in this place since the seventeenth century.

Spitalfields still has two buildings that once housed soup kitchens. The Spitalfields Soup Society functioned on Brick Lane from the late-eighteenth century and the London Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor operated on Brune Street from 1902. Both these institutions were deeply embedded in the community and have long histories.

However these were not the first soup kitchens in Spitalfields. Soon after Huguenot refugees settled in the second half of the seventeenth century, they set up La Soupe. Although soup had been used charitably almost since it was invented, this was the first institution in England set up to serve soup. One reason for providing soup rather than money was that benefactors repeatedly claimed beneficiaries “wickedly disposed of the money in tobacco and brandy.” Thus the “advantage” of soup was that it was hard to trade or sell. Additionally, La Soupe carried out careful casework before issuing soup, investigating the circumstances of each applicant to ensure they really deserved the help.

Between 1689 and 1826 when it closed, La Soupe moved several times, yet always in the vicinity of the Spitalfields market. After 1741, it seems to have stopped providing soup and distributed bread and meat instead. At the same time, local residents weew also providing soup to the less well-off. Newspapers in 1767 reported that “a gentleman” was giving soup to more than fifty Spitalfields poor from his house and John Gray, a Quaker journeyman pewterer, is recorded as regularly taking soup to his neighbours in the late-eighteenth century. Extreme poverty grew commonplace when the silk industry entered its long decline and the Society of Friends was at the forefront of the local philanthropy.

The late 1790s were times of great hardship for the poor across Britainas the Napoleonic wars, recession and high food prices brought famine. In Spitalfields, the silk industry was hit by falling demand and competition from smuggled silk. This great distress prompted two friends, William Phillips and William Allen, to organise a soup charity which became the best known soup kitchen in the country. Others sought its advice or bought the manuals it published. Its relationship to La Soupe is unclear. William Allen grew up in Spitalfields on Steward St where his father, Job Allen, was a silk weaver. So William must have known of La Soupe’s existence and history, although it is never mentioned in the surviving documents.

The “Society for supplying the Poor with a good and nutritious Meat Soup established in Spitalfields in 1797,” as its minute book proudly proclaims, was set up in late 1797, yet did not start supplying soup until the following January. When advertising in the press, they wisely shortened its name to the “Spitalfields Soup Society.” It seems to have operated until the early twentieth century as a soup kitchen and was still in existence as a charity in the sixties.

Although almost none of the founding committee were Spitalfields residents or associated with the silk trade (Allen was a chemist of distinction and Phillips a printer) the soup kitchen responded to the ups and downs of the silk industry throughout the ensuing century, opening when downturns threw thousands out of work and closing when times improved again. The list of committee members and donors was a catalogue of the City’s burgeoning banking and insurance sector, with Barclays, Hoares, Gurneys and others digging deep in their pockets. The partners in the Truman & Hanbury Brewery became the principal organisers until handing over control to the Rector of Christ Church in 1883.

The soup house ( the term “soup kitchen” was not widely used until the mid-nineteenth century) always remained at the same address, although the building was reorganised at some point before the 1860s when the famous print below from the Illustrated London News of the soup kitchen was engraved. As the picture shows, the soup kitchen, located behind the shops on the street frontage, was always busy when open. For six days a week, it served beef soup between 2,000 and 4,000 people from Spitalfields and neighbouring parishes.

The other principal soup kitchen in the neighbourhood was the London Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor. This started life in 1800 in the corner of Duke’s Place, Aldgate near the Great Synagogue, but closed around 1802. The Jewish soup kitchen was refounded in 1854 in Whitechapel when immigration from Eastern Europe increased significantly and moved north to Fashion Street in 1866 as the Jewish community expanded northward.

By the 1890s, the increasing number of Jewish refugees meant that these premises, squeezed into a stable yard, were no longer viable and – as is ever the case in Spitalfields – they were to be redeveloped. So the charity raised £10,000 to build the Brune Street premises which opened in 1902. Here several thousand received soup and bread every day. This fine building was a strong statement that the Jewish community would look after its poor and it only ceased operations after the Second World War.

There have been several other soup kitchens in the area. In around 1795, five ordinaries (an ordinary was the equivalent of a café) in Spitalfields were paid by a charitable subscription raised in the City to provide half-price soup to the poor (there were a further sixteen ordinaries selling subsidised soup in Shoreditch, Bethnal Green and Whitechapel). Two of the Spitalfields ordinaries were on Brick Lane, one at either end, and the others were on Fashion Street, Lamb Street and Smock Alley (now Artillery Passage). The Smock Alley building is now occupied by Ottolenghi’s Restaurant. The proprietor of this ordinary, George Franklin, continued providing soup to the local poor for twenty years. Another large soup kitchen operated between 1847 and about 1855 at St Matthias’ Chapel on St John Street (now under the railway).

This significant element of the Spitalfields history has been largely forgotten and the documents lost or scattered. Yet, even piecing together the story from remaining fragments, it is clear that these charities and individuals provided an invaluable service in supplying sustenance to a significant proportion of the population when no other form of welfare was available.

The Jewish Soup Kitchen in Fashion St, 1867 (Illustrated London News)

The Jewish Soup Kitchen in Spitalfields, 1879 (Illustrated London News)

The Jewish Soup Kitchen in Spitalfields, 1990, photographed by Stuart Freedman

Groceries awaiting collection

A volunteer offers a second hand coat to an old lady

An old woman collects her grocery allowance

A volunteer distributes donated groceries

View from behind the hatch

A couple await their food parcel

An ex-boxer arrives to collect his weekly rations

An old boxer’s portrait, taken while waiting to collect his groceries

An elderly man leaves the soup kitchen with his supplies

Photographs copyright © Stuart Freedman

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Philip Marriage In Spitalfields

On the corner of Gun St & Brushfield St, 1967

In Spitalfields, the closure of the Truman Brewery in 1989, the moving of Fruit & Vegetable Market in 1991 and the subsequent redevelopment of the site in 2002, have changed our neighbourhood so rapidly that even the recent past – of the time before these events – appears now as the distant past. Time has mysteriously accelerated, and we look back from the other side of the watershed created by these major changes to a familiar world that has been rendered strange to us.

Such was my immediate reaction, casting my eyes over Philip Marriage’s photographs. Between 1967 and 1995, Philip visited Spitalfields regularly taking photographs, after discovering that his ancestors lived here centuries ago. And the pictures which are the outcome of his thirty-year fascination comprise a spell-binding record of these streets at that time, taken by one on a personal quest to seek the spirit of the place.

“I worked in London from 1959 to 1978 and, for the first ten years, I commuted from Enfield to Liverpool St Station. So I was aware of Spitalfields from that time, though my real interest started when I discovered that my great-great-grandfather was a silk weaver at 6 Duke St, Old Artillery Ground. And I found records of others sharing the Marriage (then French Mariage) surname in the area as far back as 1585.

My job – as a graphic designer and later Design Manager – for HMSO Books (the former government publishers) was based on Holborn Viaduct so I was near enough to Somerset House, the Public Records Office and the Guildhall Library to undertake family history research in my lunchtime. In the autumn of 1967, I visited Spitalfields with my camera for the first time to see if I could locate any of the places associated with my family. In those days colour print film was expensive and I mostly took transparencies, but later Ilford brought out a cheap colour film for a pound a roll which provided twenty small colour prints and each negative returned mounted in 2×2 cardboard mounts – quite novel, but affordable.

When I married in 1968 and moved to Hertfordshire, my family history researches came to an end. Then, in 1978, my job took me to Norwich where I’ve remained since. However, I occasionally found myself in London and, if time permitted whilst waiting for the Norwich train, I always nipped out of Liverpool St Station and down Brushfield St for a brief reminder of my favourite places.”

Crispin St, 1985.

Spital shop, 1970.

Parliament Ct, 1986.

H.Hyams, Gun St, 1970.

Corner of Fashion St & Brick Lane, 1979.

Fashion St, 1979.

Toynbee St, 1970.

The Jolly Butchers, Brick Lane, 1985.

The Crown & Shuttle, Norton Folgate, 1987.

Boundary Passage with The Ship & Blue Ball, 1985.

The Carpenter’s Arms at the corner of Cheshire St & St Matthew’s Row, 1985.

Brick Lane, 1985.

Tour in Hanbury St, 1985.

Corner of Wentworth St & Leyden St, 1990.

Brushfield St, 1990.

Mosley Speaks, 1967.

Fournier St, 1985.

Corner of Quaker St & Grey Eagle St, 1986.

Truman Brewery, Brick Lane, 1985.

E. Olive Ltd, Umbrella Manufacturers, Hanbury St, 1985.

E. Olive Ltd, Umbrella Manufacturers, Hanbury St, 1985.

Corner of Lamb St & Commercial St, 1988.

Brushfield St, 1990.

Spitalfields Market, 1986.

Brushfield St, 1985.

Gun St, 1985.

Brushfield St, 1985.

Christ Church, Spitalfields, 1985.

Photographs copyright © Philip Marriage

You may also like to look at

Alan Dein’s East End Shopfronts of 1988

Mark Jackson & Huw Davies, Photographers

Dave Thompson, Joiner

In Spitalfields, Dave Thompson is famous for the blue overalls he has worn as long as anyone can remember, popular for the apples and eggs he brings up fresh from Kent each day, but – most of all – he is celebrated for his superlative joinery.

Over the last fifteen years, Dave has been at the core of a group of craftsmen who have worked continuously upon the renovation of the eighteenth century houses and, as a result, he has earned the affections of many of the owners. They treasure Dave for the skill and application he brings to his work, yet such is his magnanimous nature that he chooses to reciprocate their appreciation of his talent with regular deliveries of apples and eggs. Thus it has come to be understood, among those who dwell in the ancient streets beside Christ Church, that only when you are in receipt of Dave’s deliveries from Kent can you truly be said to have arrived in Spitalfields.

To seek Dave, you have to look in a special place secluded from the public gaze and known only to the initiated. On the Eastern side of Brick Lane lies part of the Truman Brewery once inhabited by dray horses and coopers, here in an old cobbled yard stands a crumbling stable block where at its furthest extremity, framed by an elegant brick arch, you will find Dave’s workshop. Any residual doubt whether this is the correct location will be assuaged by the presence of the massive pile of scrap timber you see tossed to the right of the arch.

Yet, by the time you reach the woodpile, you will very likely already have heard the sound of Dave’s machine tools roaring within his workshop, and you will know that this is the place and Dave is inside at work. Certainly, this was my experience when I arrived and opened the door to be greeted by Dave’s smile, his blue overalls standing out in sharp contrast to the yellow wood shavings and sawdust that surrounded him.

I come from a little village, Loose near Maidstone in Kent. At school, I learnt what I could do and I started off in furniture making at Maidstone Art College where I did City & Guilds Carpentry and Joinery, basic and advanced. Then I worked as a cabinet maker in a furniture factory for eight years, making fireside chairs and stuff like that, and I worked in East Farleigh making bespoke kitchens. I was lucky to get the chance to come to London but it was a big gamble – I was offered the choice of being made redundant and getting five thousand pounds, so I took it.

When I first came up to Spitalfields fifteen years ago, I was restoring 1 and 3 Fournier St for James Hutcheson. He had a showroom at the front and I had my workshop at the back, but after three years he sold number 3 to Marianna Kennedy & Charles Gledhill, and I worked for them. That was six years of my life, then I moved over to the Truman Brewery stable block. I knew nothing about the restoration of old buildings when I first come up here but I learnt a lot working with Jim Howett, he’s been here thirty years and he’s got a lot of specialist knowledge.

If you can do something like mouldings, everybody wants you to make them because in every old house the mouldings are different. One of my specialities is fitting shutters in rooms that don’t have shutter cases and making new panelling. I’ve done a lot of external shutters in Wilkes St and Princelet St. When you do restoration, you try to use the old timber. Often if the panelling is damaged, you can patch it up and put it back. It was all good work they did in the old days. They didn’t have the tools but they had all the time in the world. I’ve never had to look for work, I’ve been up here so long now that people just come to me – but it’s been hard, for years I got up at four thirty every morning to get into London by six.

In Eleanor Jones’ house in Fournier St, I put in a big pair of curved doors on the first floor that are the same as on the ground floor. I had a lot of curved work to do the bay window and Bogdan helped me, he was a very good joiner from Poland. The two of us put our heads together and sorted that out. One day, he came in and said he’d been to the specialist. It was cancer. He’d had his chips. He did quite a lot of work around here and extensively renovated the Market Coffee House. He was one of the best.

Since then, I’ve done a lot of work for people in Fournier St. When I started, I used to fit shutters, internal and external, but most of the time now, I’m doing work for people making joinery for their carpenters to fit on site. As you get older and wiser, you don’t fit it, you make it and leave that to someone else. Matt Whittle and Tony Clarence are two blokes I work with, we started at the same time fifteen years ago. There was quite a little gang of people and we all got to know each other and we’d be working together restoring the same houses. Sometimes, the people would sell the houses, and we’d get paid to rip out the work we did and then do it all over again to suit the new owner.

About three years ago, I had a quadruple heart bypass. I used to work quite long hours but now all I do is get in at six and work until three, four days a week. Not so stressful. I’ve got an old farm cottage in Loose. Unfortunately, it’s only a two bedroom cottage. I restored it myself and I like to be comfortable. I’m sixty-five in April, I don’t think I’ve got many more years – though it is getting to the stage in Spitalfields where there is less and less to do. But I’ve left my mark and I’m proud of the work I’ve done here.”

One day – to his alarm – Dave saw that some contractors had tried to cut corners by tearing an eighteenth century door case off the front of a house in Wilkes St and throwing it in a skip. Yet thankfully, when the building inspectors enforced the listed status of the building, it was Dave who got the painstaking job to piece the fragments back together and reconstruct it with the help of Diana Reynell (a grotto designer) who restored the mouldings. And the dignified door case in question stands today, as if it had never been broken.

The emotionalism with which this event is charged for Dave reveals the depth of his personal involvement with these old houses. His conscientious labour over all these years has comprised the culmination of his life’s work and it honours those craftsmen whose work he has furthered.

Even as Dave and his fellows have pursued the long task of restoring these buildings, residents have come and gone, raising the question of who – if anybody – truly has ownership of these properties. Because, as much as these buildings manifest the status and taste of their occupants, they also commemorate the talents of the artisans who have worked upon them, both recently and long ago.

Dave worked on the restoration of 1 Fournier St in the nineteen-nineties

Fragments of the eighteenth century doorcase torn from the wall but rescued from the skip in Wilkes St

The eighteenth century doorbox re-instated by Dave at number 13 Wilkes St and replicated at number 1

Doorboxes at 7 & 9 Fournier St by Dave, commissioned by neighbours John Nicolson and Kate Jenkins

Dave Thompson, joiner, outside his workshop in the former stable of the Truman Brewery

You may also like to read about

Michelle Mason’s Flower Market

As you know, I always go to Columbia Rd Market each Sunday to buy a bunch of flowers. And I often pop in to visit Michelle Mason who has been running a shop there for several years and complements her displays with flowers from the market.

Growing fascinated by the changing varieties through the seasons of the year, Michelle began photographing her arrangements and now she has written a beautiful book, FLOWER MARKET, Botanical Style At Home, which is full of inspiration to create your own imaginative floral displays.

Michelle will be demonstrating how it is done at Townhouse Spitalfields on Tuesday 21st May at 6:30pm as past of the Chelsea Flower Show Festival Fringe. Click here for tickets

“Summer show-stoppers include blowsy Peonies, Roses, Foxgloves and Lupins and as the season unfurls through the warmer months of June, July and August the variety of flowers and foliage reaches its most glorious peak. This is, no doubt, the most productive and creative time for growers and florists as they prepare for summer weddings and other events.”

“I love the scent of early summer Stocks and the gorgeous apricot variety I used here filled the entire room with a sweet clove-like fragrance. Using an old glass jar I added white Anenomes, coral pink Freesia, zesty Ranunculus and a peach tea Rose for a romantic garden feel and set it against a botanical wall chart with illustrations of Sweet Peas. This scene was inspired by flower paintings from the Dutch Golden Age of the late 1600s, when still-life paintings depicting exotic botanicals became popular.”

“As we reach May and June, the flower market comes alive with colour and variety, ranging from Peonies the size of saucers to Roses in every shape and shade, exotic oriental Poppies, Delphiniums, Cornflowers, Phlox, pear-scented Snapdragons and so many dainty and delicate meadow flowers such as Forget-me-Nots, Fennel and Mustard flowers. The choice is overwhelming.”

“This botanical illustration from the twenties sets the tone for a delicately faded scene. The caramel-coloured Rose was the starting point for the flowers and I added the fragrant cream double Daffodils with a buttery yellow centre, aptly named ‘Cheerfulness’, with Hazel twigs, white Freesia and pearly butterfly Ranunculus.”

“This palette of spring colour, randomly arranged on a metal table, includes soft pink Primroses, Tulips, Grape Hyacinths, orange Ranunculus, yellow and blue Hyacinths, cream Freesia, Snowdrops and white Wax Flower.”

“Using old fabrics is a way to layer pattern and colour, and I especially like to use hessian, hemp and plain linens to add tone and texture, such as this sugar sack. The worn, faded cloth, stamped with Tate & Lyle, makes an attractive backdrop to the pale floral arrangement of white Lilac, Tulips with honey-coloured centres, cream Narcissi and palest pink Viburnum.”

“Winter displays need not be limited to evergreens and dried leaves. November offers colour like these caramel-coloured Ranunculus, Anemones and rosy apricot, peach and yellow late-flowering Iceland Poppies.”

“Beautiful, sweet-smelling Peonies are the quintessential summer blooms. They range from the ruffle- feathered pink blush variety ‘Sarah Bernhardt’ to the deep burgundy ‘Rubra Plena’ and the white ‘Alba Plena’, all of which have large velvety double flowers. ‘Coral Sunset’, a little less full-flowered but equally pretty, with a gold and apricot centre, reminds me of my grandmother’s garden.”

” In April and May the larger peony-like, fuller-flowered tulip varieties come on to the market in a blaze of colour from scorching hot reds to ballet-slipper pinks, yellows and ivory streaked with peach. ”

“Traditional flowers such as Forget-me-Nots, trailing Honeysuckle, wild sweet Briar, Lily-of-the-Valley (symbolising happiness), Lupins, Larkspur and Foxgloves make dreamy summer bouquets and add unusual elements to wedding flowers.”

“Little posies of peony Ranunculus, pink Viburnum blossom and Ammi Majus (a form of cow parsley sometimes known as Bishop’s Flower) in a collection of glassware from cloudy eau de vie bottles, chemists’ bottles, inkpots and an old jam jar.”

Photographs copyright © Michelle Mason

Click here to buy a copy of FLOWER MARKET by Michelle Mason direct from Pimpernel Press

Other CHELSEA FLOWER SHOW FRINGE EVENTS at Townhouse

BEE URBAN, between 2:30-4:30pm Saturday 18th May

The beekeepers who tend the bees on the roof of the National Theatre and the South Bank Centre will be displaying a mobile observation beehive. (No booking necessary)

THE BETHNAL GREEN MULBERRY, 6:30pm Wednesday 22d May

The Gentle Author tells the story of the campaign to save the East End’s oldest tree. (Click here to book)

EDIBLE LANDSCAPES, 12:30pm Thursday 23rd May

Jo Honan talks about how to identify edible plants and trees, including, lovage, saltbush, jostaberry, medlar, calendala and allium. Lecture includes a light lunch of edible plants. (Click here to book)

The Secrets Of Christ Church

There is a such a pleasing geometry to the architecture of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church, Spitalfields, completed in 1729, that when you glance upon the satisfying order of the facade you might assume that the internal structure is equally apparent. Yet it is a labyrinth inside. Like a theatre, the building presents a harmonious picture from the centre of the stalls, yet possesses innumerable unseen passages and rooms, backstage.

Beyond the bellringers’ loft, a narrow staircase spirals further into the thickness of the stone spire. As you ascend the worn stone steps within the thickness of the wall, the walls get blacker and the stairs get narrower and the ceiling gets lower. By the time you reach the top, you are stooping as you climb and the giddiness of walking in circles permits the illusion that, as much as you are ascending into the sky, you might equally be descending into the earth. There is a sense that you are beyond the compass of your experience, entering indeterminate space.

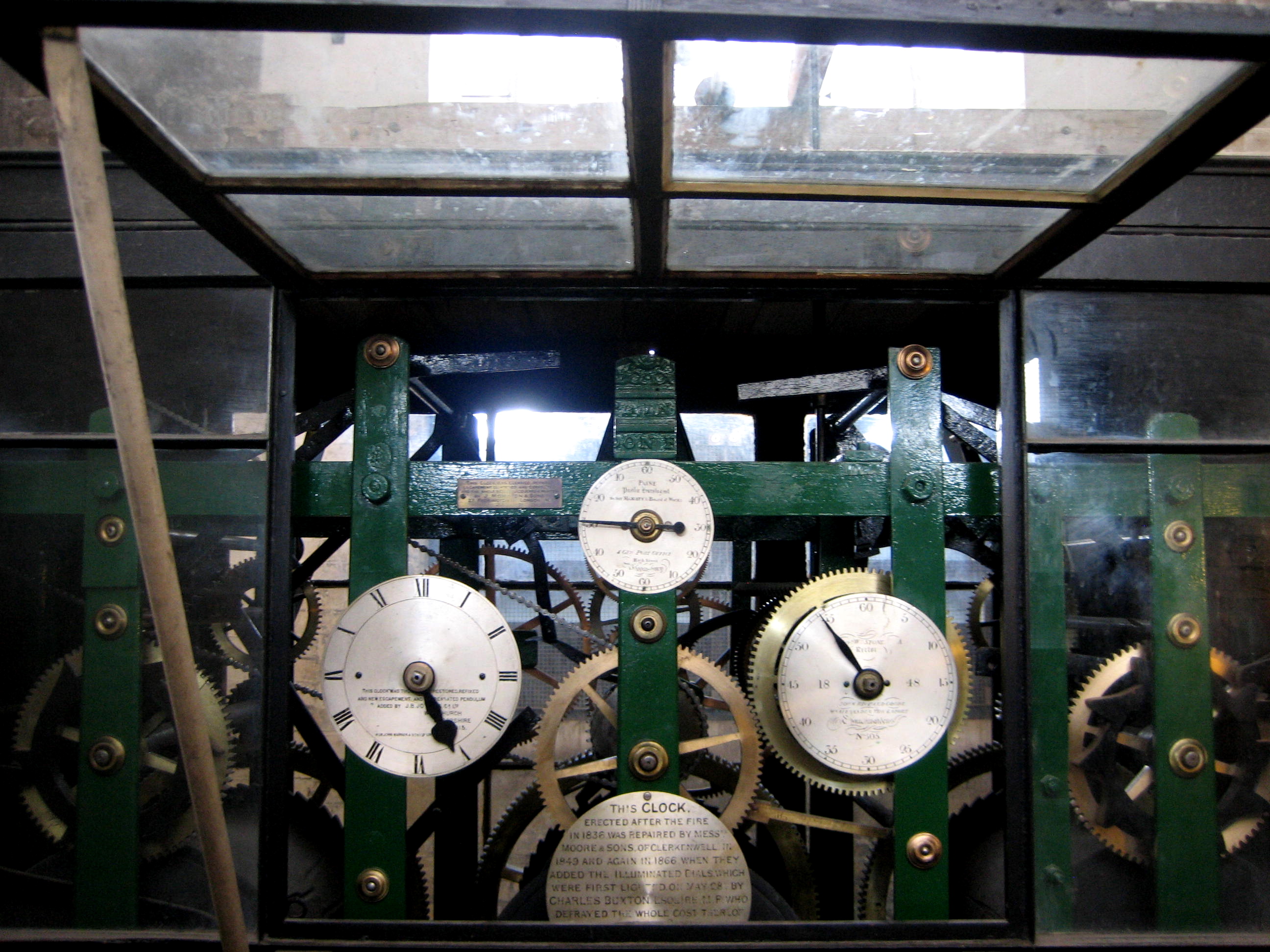

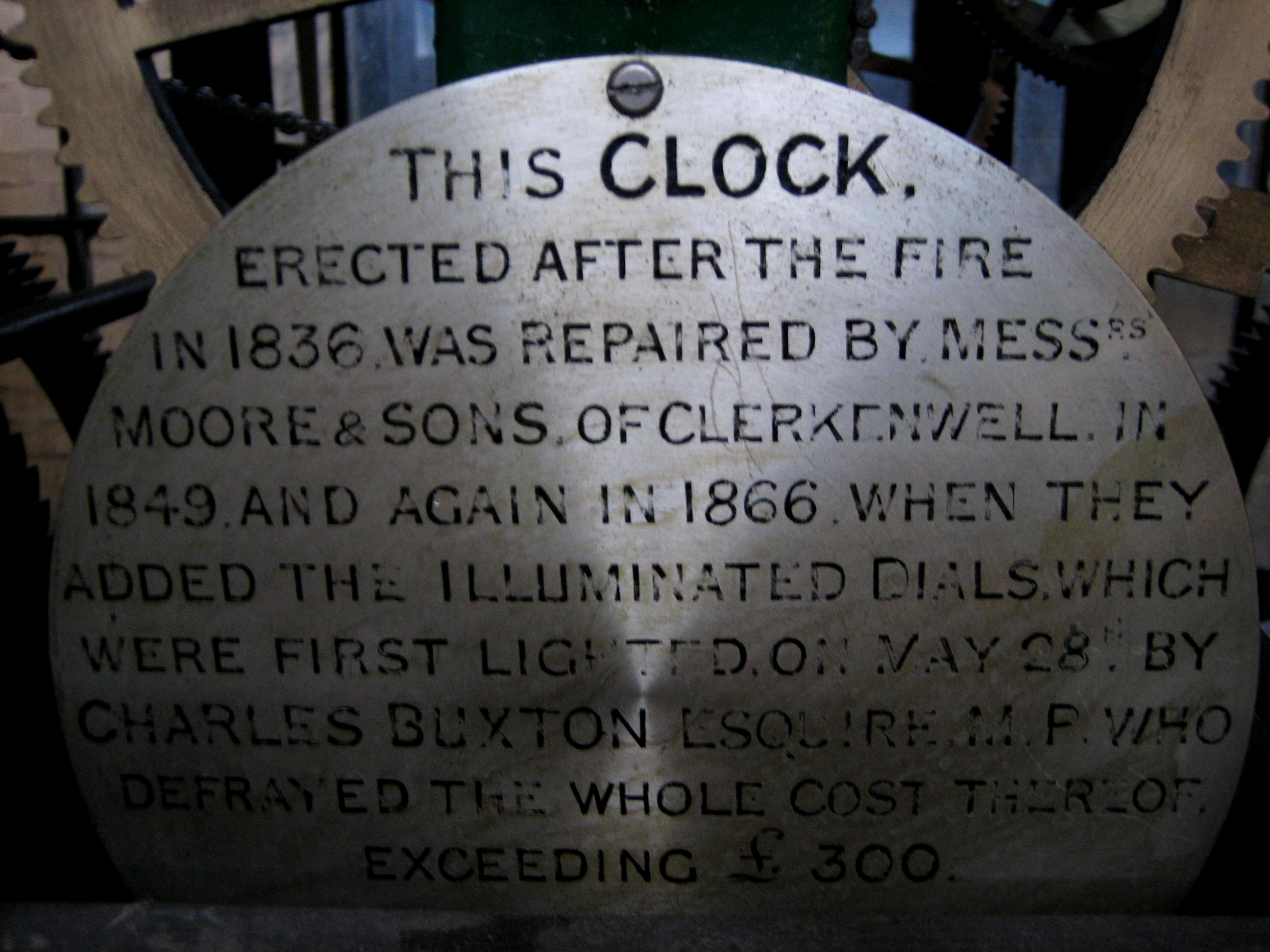

No-one has much cause to come up here and, when we reached the door at the top of the stairs, the verger was unsure of his keys. As I recovered my breath from the climb, while he tried each key in turn upon the ring until he was successful, I listened to the dignified tick coming from the other side of the door. When he opened the door, I discovered it was the sound of the lonely clock that has measured out time in Spitalfields since 1836 from the square room with an octagonal roof beneath the pinnacle of the spire. Lit only by diffuse daylight from the four clock faces, the renovations that have brightened up the rest of the church do not register here.

Once we were inside, the verger opened the glazed case containing the gleaming brass wheels of the mechanism, turning with inscrutable purpose within their green-painted steel cage, driving another mechanism in a box up above that rotates the axles, turning the hands upon each of the clock faces. Not a place for human occupation, it was a room dedicated to time and, as intervention is required only rarely here, we left the clock to run its course in splendid indifference.

By contrast, a walk along the ridge of the roof of Christ Church, Spitalfields, presented a chaotic and exhilarating symphony of sensations, buffered by gusts of wind beneath a fast-moving sky that delivered effects of light changing every moment. It was like walking in the sky. On the one hand, Fashion St and on the other Fournier St, where the roofs of the ighteenth century houses topped off with weavers’ lofts create an extravagant roofscape of old tiles and chimney pots at odd angles. Liberated by the experience, I waved across the chasm of the street to residents of Fournier St in their rooftop gardens opposite, just like waving to people from a train.

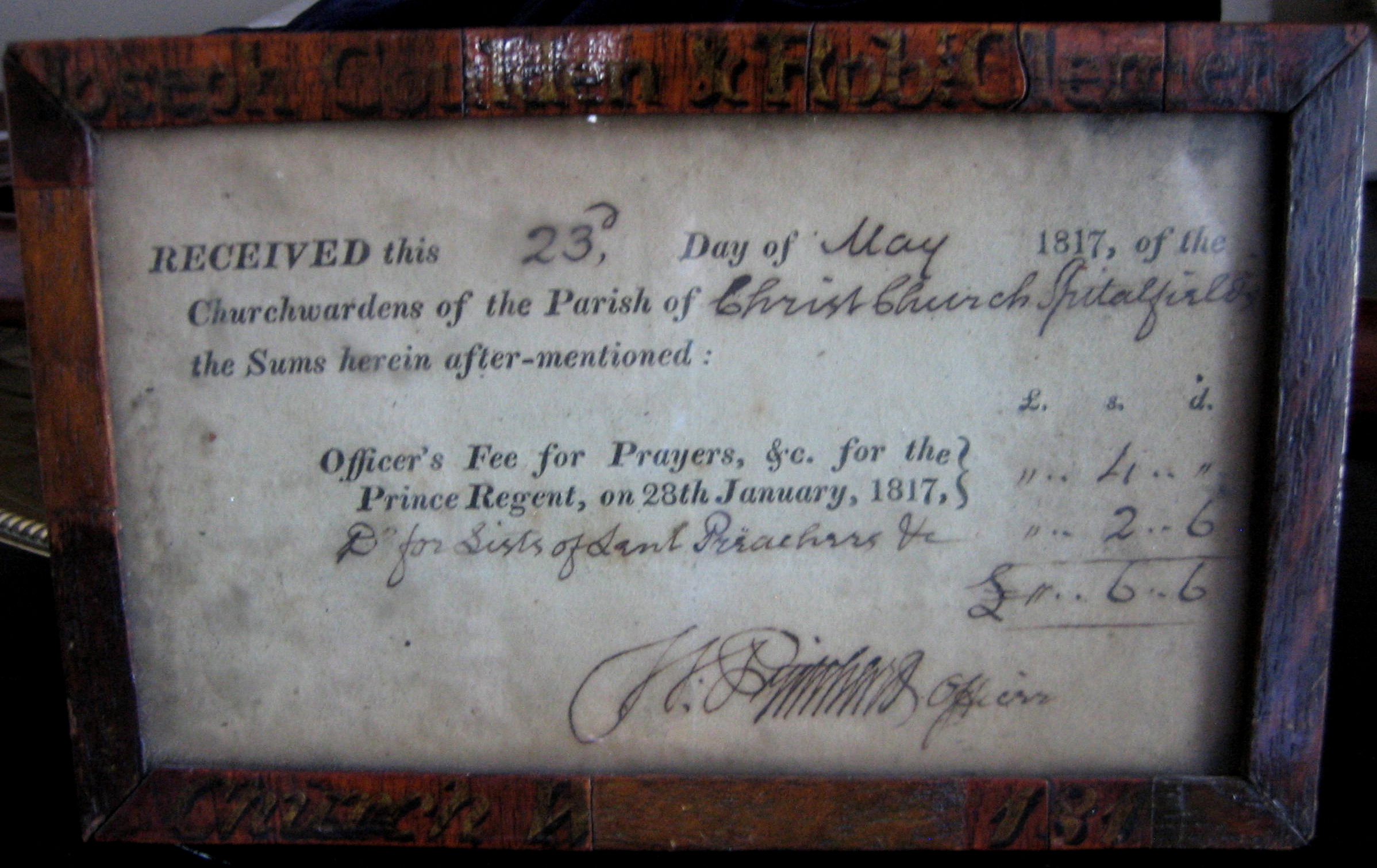

Returning to the body of the church, we explored a suite of hidden vestry rooms behind the altar, magnificently proportioned apartments to encourage lofty thoughts, with views into the well-kept rectory garden. From here, we descended into the crypt constructed of brick vaults to enter the cavernous spaces that until recent years were stacked with human remains. Today these are innocent, newly-renovated spaces without any tangible presence to recall the thousands who were laid to rest here until it was packed to capacity and closed for burial in 1812 by Rev William Stond MA, as confirmed by a finely lettered stone plaque.

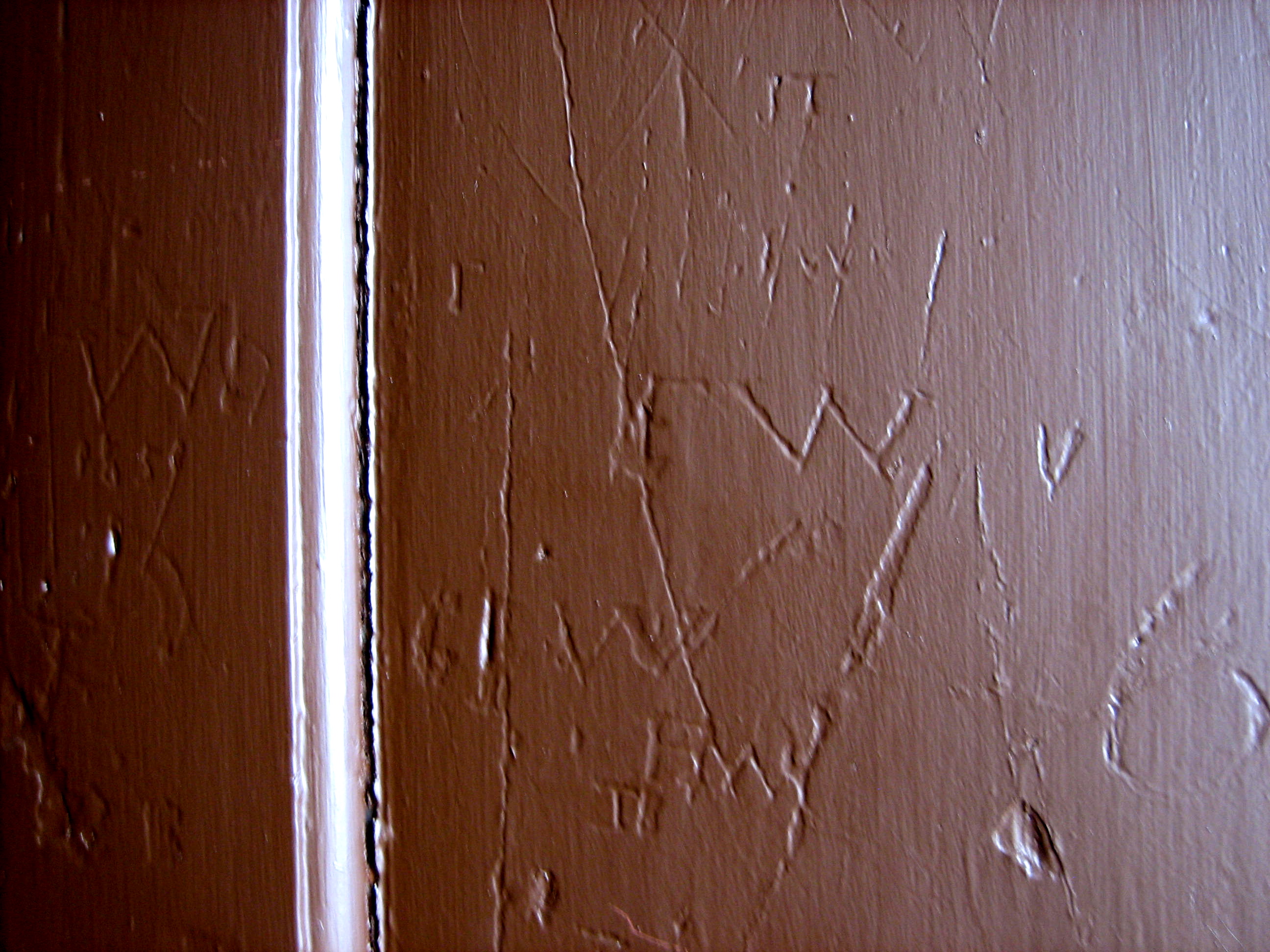

Passing through the building, up staircases, through passages and in each of the different spaces from top to bottom, there were so many of these plaques of different designs in wood and stone, recording those were buried here, those who were priests, vergers, benefactors, builders and those who rang the bells. In parallel with these demonstrative memorials, I noticed marks in hidden corners, modest handwritten initials, dates and scrawls, many too worn or indistinct to decipher. Everywhere I walked, so many people had been there before me, and the crypt and vaults were where they ended up.

My visit started at the top and I descended through the structure until I came, at the end of the afternoon, to the small private vaults constructed in two storeys beneath the porch, where my journey ended, as it did in a larger sense for the original occupants. These delicate brick vaults, barely three feet high and arranged in a crisscross design, were the private vaults of those who sought consolation in keeping the family together even after death. All cleaned out now, with modern cables and pipes running through, I crawled into the maze of tunnels and ran my hand upon the vault just above my head. This was the grave where no daylight or sunshine entered, and it was not a place to linger on a bright afternoon in May.

Christ Church gave me a journey through many emotions, and it fascinates me that this architecture can produce so many diverse spaces within one building and that these spaces can each reflect such varied aspects of the human experience, all within a classical structure that delights the senses through the harmonious unity of its form.

The mechanism of this clock runs so efficiently that it only has to be wound a couple of times each year

Looking up inside the spire

A model of the rectory in Fournier St

On the reverse of the door of the organ cupboard

In the vestry

For nearly three centuries, the shadow of the spire has travelled the length of Fournier St each afternoon

You may also like to read about

Harry Landis, Actor

“I was born and brought up in the East End, then I went away for fifty years and came back eight years ago – but I returned to a very different East End from the one I left,” admitted Harry Landis, as we stood together outside the former Jewish Soup Kitchen in Brune St.

“When I was four years old, I came here with my mother holding me in one hand and a saucepan in the other, to get a dollop of soup and a loaf of bread.” Harry confided to me, “When I returned, the soup kitchen had been converted into flats, and I thought it would be great to buy a flat as a reminder – but the one for sale was on the top floor with too many stairs, so I didn’t buy it. Yet I’d have loved that, living in the soup kitchen where I went as a child.”

“I don’t feel any sense of loss about poverty and the bad old days and people suffering,” Harry declared with a caustic grin, as we ambled onward down Brune St. And when Harry revealed that growing up in Stepney in the nineteen thirties, he remembers taking refuge in his mother’s lap at the age of ten when a brick came smashing through their window – thrown by fascists chanting, “Get rid of the Yids! Get rid of the Yids!” – I could understand why he might be unsentimental about the past.

We walked round into Middlesex St to the building which is now the Shooting Star, that was once the Jewish Board of Guardians where Harry’s mother came to plead her case to get a chit for soup at the kitchen. “I hate those jumped up Jews who blame poor Jews for letting down the race,” Harry exclaimed to me, in a sudden flash of emotion as we crossed the road, where he accompanied his mother at four years old to face the Board of Guardians sitting behind a long table dressed in bow ties and dinner jackets.

When she told the Board she had two children – even though she only had Harry – in hope of getting more of the meagre rations, the Guardians unexpectedly challenged Harry, requiring evidence of his mother’s claim. With remarkable presence of mind for a four year old, he nodded in confirmation when asked if he had a sister. But then the Guardians enquired his sister’s name, and – in an extraordinary moment of improvisation – Harry answered, “Rosie,” and the Board was persuaded. “She used to break her loaf of bread and give half to the poor Christians waiting outside the soup kitchen,” he told me later, in affectionate recognition of his mother’s magnanimous spirit, even in her own state of poverty.

Yet the significance of Harry’s action reverberated far beyond that moment, because it revealed he had a natural talent for acting. It was a gift that took him on a journey out of the East End, gave him a successful career as an actor and director, and delivered him to the Royal Court Theatre where he originated the leading role in one of the most important post-war British plays, Arnold Wesker’s masterpiece “The Kitchen.” Although, ironically, at Stepney Jewish School where Harry was educated, the enlightened headmistress, Miss Rose, made the girls do woodwork and the boys learn cooking – and when Harry left at fourteen he wanted to become a chef in a kitchen, but discovered apprenticeships were only available to those of sixteen.

“They sent me to work in a cafe pouring tea but I didn’t last very long there, I did several jobs, window cleaner and milkman. And I used to go to the Hackney Empire every week, first house on a Monday because that was the cheapest – the company had just arrived, rehearsed with the band once and they were on at six, but the band weren’t sure what they were doing, so I enjoyed watching it all go wrong.

Being a cheeky little sod, I used to perform the show I’d seen on the Monday night next day at the factory where I worked – Max Miller’s jokes, the impersonators and Syd Walker who did a Rag & Bone act. 95% of them nobody knows now. “The shop steward, who was my mentor said, “You ought to be on the stage.”I’d never seen a play. I said, “Where do I go to see a play?” He said, “If you go the West End, the play will be about the tribulations of the upper classes, the problems of posh people. But there is one theatre in Kings Cross called the Unity Theatre, the theatre of the Labour & Trade Union Movement that does plays about ordinary people. I’m going there next Sunday night with my wife, if you’d like to come.” And I went. And at the Unity Theatre, that’s where my life changed.

It knocked me out because the people on the stage could have been living in my street and the language they spoke was the language we all spoke down the East End. The shop steward said, “You should be here, I’ll get you an audition.” I did my audition and I showed them my acting of bits I’d seen at the Hackney Empire, and they put me in the variety group. We performed shows in air raid shelters and parks. But then they transferred me to the straight acting section because I was fifteen and there was a shortage of men since they were all away at war. I was playing above my years but learning to act.

After two or three years of this and doing my military service, I returned to the Unity Theatre and the headmaster of a South London school saw me and said, “You should be professional, why don’t you apply for a grant from the London County Council to go to drama school?” I was twenty. He got me the form and we filled it out, and I was given a grant and money to live on. How times have changed! I did three years at Central School of Speech & Drama. You learnt RP (Received Pronunciation) but you never lost your own speech. I was considered a working class actor.

“I got cast in a wonderful play at the Royal Court Theatre, run by George Devine where they did the plays of John Osborne. It was “The Kitchen” by Arnold Wesker, and I played the part of Paul, the pastry cook – which is the Arnold Wesker character – that’s what he did when he worked in a kitchen. It was about himself. Arnold wrote without any knowledge of theatre, which is to say a play with twenty-five actors in it which only lasts seventy-five minutes. People said they could see the food we were cooking but it was all mimed…”

So Harry fulfilled his childhood ambition to become a chef – on stage – through his work as an actor in the theatre. To this day, he gratefully acknowledges his debt to the Unity Theatre and those two individuals who saw his potential – “I was going to be an amateur but I was pushed to the next stage,” he accepts. Harry enjoyed success as one of a whole generation of talented working class actors that came to prominence in the post-war years bringing a new energy and authenticity to British drama. Now Harry Landis has returned to his childhood streets and laid the ghosts of his own past, he is happy to embrace the changes here today, although he does not choose to forget the East End he once knew.

“It’s a different East End. The bombs got rid of a lot and it’s all been rebuilt. The Spitalfields Market is full of chains and it’s been gentrified, and you’ve got your Gilbert & Georges and your Tracey Emins, and the place is full of art studios and it’s become the centre of the world. It’s the new Chelsea. I sold my house in Hammersmith where I lived for forty years (that I bought for £2,000 with 100% mortgage from the LCC) and I came back and bought a flat here in Spitalfields with the proceeds. And the rest I put in the bank for when I am that constant thing – an out of work actor!”

Outside the soup kitchen in Brune St where Harry came with his mother at the age of four

At the former Jewish Board of Guardians in Middlesex St

Harry as Private Rabin in “A Hill in Korea,” 1956

Harry Landis

The Bethnal Green Gasometers

If you care about the fate of the Bethnal Green gasometers, I recommend you attend the public consultations held by St William Homes (a joint venture by National Grid and the Berkeley Group) who are currently considering the option of retaining the gasometers as part of their redevelopment of the site.

The exhibition takes place this Saturday 11th May from 11:00am – 4:00pm, Monday 13th from 3:00pm – 7:00pm and Tuesday 14th from 11:00am – 3:00pm at the Redeemed Christian Church of God, 7-8 The Oval, Bethnal Green, E2 9DT.

Behold the majestic pair of gasometers in Bethnal Green, planted regally side by side like a king and queen surveying the Regent’s Canal from aloft. Approaching along the towpath, George Trewby’s gasometer of 1888-9 dominates the skyline, more than twice the height of its more intricate senior companion designed by Joseph Clarke in 1866.

Ever since these monumental gasometers were granted a ‘certificate of immunity against listing’ by Historic England, which guarantees they will never receive any legal protection from destruction, their fate has been in the balance.

The Bethnal Green gasometers were constructed to contain the gas that was produced by the Shoreditch Gas Works, fired by coal delivered by canal. The thick old brick walls bordering Haggerston Park are all that remains today of the gas works which formerly occupied the site of the park, built by the Imperial Gas Light & Coke Company in 1823.

Crossing Cat & Mutton Bridge, named after the nearby pub founded in 1732, I walked down Wharf Place and into Darwen Place determining to make as close a circuit of the gasometers as the streets would permit me.

Flanked by new housing on either side of Darwen Place, the gasometers make a spectacularly theatrical backdrop to a street that would otherwise lack drama. Dignified like standing stones yet soaring like cathedrals, these intricate structures insist you raise your eyes heavenward, framing the sky as if it were an epic painting contrived for our edification.

Each storey of Joseph Clarke’s structure has columns ascending from Doric to Corinthian, indicating the influence of classical antiquity and revealing the architect’s chosen precedent as the Coliseum, which – if you think about it – bears a striking resemblance to a gasometer.

As I walked through the surrounding streets, circumnavigating the gasometers, I realised that the unapproachable nature of these citadels contributes to their magic. You keep walking and they always remain in the distance, always just out of reach yet looming overhead and dwarfing their surroundings. In spite of the utilitarian nature of this landscape, the relationship between the past and present is clear in this place and this imparts a strange charisma to the location, an atmosphere enhanced by the other-wordly gasometers.

After walking their entire perimeter, I can confirm that the gasometers are most advantageously regarded from mid-way along the tow path between Mare St and Broadway Market. From here, the silhouette of George Trewby’s soaring structure may be be viewed against the sun and also as a reflection into the canal, thus doubling the dramatic effect of these intriguing sky cages that capture space and inspire exhilaration in the beholder.

We hope that the developer recognises the virtue in retaining these magnificent towers and integrating them into their scheme, adding value and distinction to their architecture, and drama and delight to the landscape.

The view from Darwen Place

Decorative ironwork and classical columns ascending from Doric to Corinthian like the Coliseum

The view from Marian Place

The view from Emma St

The view from Corbridge St

The view from Regent’s Canal towpath

George Trewby’s gasometer of 1888 viewed from Cat of Mutton bridge over Regent’s Canal

You may also like to read