Philip Cunningham’s East End Portraits

In the seventies, while living in Mile End Place and employed as a Youth Worker at Oxford House in Bethnal Green and then as a Probationary Teacher at Brooke House School in Clapton, Photographer Philip Cunningham took these tender portraits of his friends and colleagues. “I love the East End and often dream of it,” Philip admitted to me recently.

Publican at The Albion, Bethnal Green Rd. “We would often go there from Oxford House where I was a youth worker. Billy Quinn, ‘The Hungry Fighter’ used to drink in there. He would shuffle in, in his slippers and, if I offered him a drink, the answer was always the same. ‘No! No! I don’t want a drink off you, I saved my money!’ He had fought a lot of bouts in America and was a great character.”

Proprietor of Barratts’ hardware – “An unbelievable shop in Stepney Way. It sold EVERYTHING, including paraffin – a shop you would not see nowadays.”

Terry & Brenda Green, publicans at The Three Crowns, Mile End

“My drinking pal, Grahame the window cleaner, knew all that was happening on the Mile End Rd.”

Oxford House bar

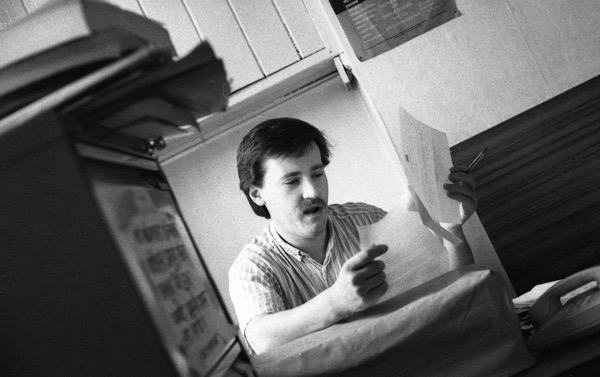

“Bob Drinkwater ran the youth club at Oxford House where I was a youth worker” c. 1974

Pat Leeder worked as a volunteer at Oxford House

Caretaker at Oxford House

My friend Michael Chalkley worked for the Bangladeshi Youth League and Bangladeshi Welfare Association

Frank Sewell worked at Kingsley Hall, Bow, and ran a second hand shop of which the proceeds went to the Hall, which was ruinous at that time

Historian Bill Fishman in Whitechapel Market

Mr Green

Kids from the youth club at Oxford House, Weavers’ Fields Adventure Playground, c. 1974

Kids from the youth club at Oxford House, Weavers’ Fields Adventure Playground, c. 1974

Salim, Noorjahan, Jabid and Sobir with Michael Chalkley, c. 1977

Coal Men, A G Martin & Sons, delivering to Mile End Place

Mr & Mrs Jacobs, neighbours at Mile End Place

Mr & Mrs Mills, neighbours at Mile End Place

Commie Roofers, Mile End Place

Friend and fighter against racism, Sunwah Ali at the Bangladeshi Youth League office, c. 1978

Norr Miah was a friend, colleague and trustee of the Bangladeshi Youth League

Chess players at Brooke House School, c. 1979

Teacher at Brooke House – “The best school I ever taught in with a really congenial staff” c. 1979

“Boys from Brooke House School where I was a probationary teacher, c.1979”

“My friend and colleague Salim Ullah with his baby” c.1977

John Smeeth (AKA John the Beard), my daughter Andrea, and Michael Wiston (AKA Whizzy) c. 1977

Eddie Marsan (dressed as Superman) and friends, Mile End Place

“Rembert Langham in our studio in New Crane Wharf, Wapping. He made monsters for Dr Who and went pot-holing”1975

Mother & son, Whitechapel. “She asked me why I was taking photos of derelict buildings, so I said I would like to take a picture of her and she agreed.”

“John the Fruit used to drink in the Three Crowns and we were good friends. We were in the pub one night when some tough characters came in. It turned out they owned this property I had been photographing. I asked if I could do some photos inside, they said, ‘Yes, come on Thursday.’ I duly arrived, but the place was locked and no one was about. Then John the Fruit turned up so I took his picture, as you see above. Later that week in the Three Crowns, the rough guys walked in and, when they saw me, accused me of not turning up. I was grabbed by the shoulder to be taken outside (very nasty). However John, who was an ex-boxer and pretty fit for an old boy, pulled the bloke holding me aside and said ‘He was there, because I was there with him!’ They put me down and were most apologetic to John. He saved me from something bad, God Bless Him!!”

Abdul Bari & friend, Whitechapel. “Abdul Bari (Botly Boy) lived in the Bancroft Estate and was a parent at John Scurr School where I was a governor and where my daughter attended. The photo was taken on Christmas day.”

Printer at the Surma newspaper, Brick Lane. The paper supported Sheikh Mujibur Rahman & the Awami League.

Porters at Spitalfields Market c.1978

Porters at Spitalfields Market c.1978

Boys on wasteland, Whitechapel c.1977

My friends Sadie & Murat Ozturk ran the kebab shop on Mile End Rd. Their daughter Aysher was best friends with my daughter and both went to John Scurr School. We spent alternate Christmases at each others’ home until they returned to Turkey. They were very hard-working and I hope they have prospered. c.1978

Engineers in the Mile End Automatic Laundry. It was a fantastic facility for people like us, with just an outside toilet and a butler’s sink in the kitchen. It had machines to iron your sheets which was a palaver, but everyone used to help each another. c.1975

Jan Alam & Union Steward, Raj Jalal on an Anti-Fascist march in Whitechapel

Chris Carpenter & Jim Wolveridge on Mile End Waste. My long-time friend Chris was a teacher at John Scurr School who went to Zimbabwe to teach for a number of years. When he arrived there were very few books in the School, but oddly there was one called ‘Ain’t It Grand’ by Jim Wolveridge. How it got there nobody could explain. Jim Wolveridge used to have a second hand book stall on the Waste every Saturday. In this photo, Chris is telling him about finding his book in his school in Zimbabwe. c.1985

My photography student Rodney at Deptford Green Youth Centre would often say ‘Hush up & listen to the Teach!’

Michael Rosen and Nik Chakraborty both taught my daughter at John Scurr School. c.1979

Photography students at Deptford Green Youth Centre. They were eager to learn and I hope they’ve all done well. c.1979

My friend and colleague, Caroline Merion at Tower Hamlets Local History Library where she spent most of her time. I went to her house once or twice and I noticed she had a habit of hoarding bags. c.1979

Harry Watton worked in the Local History Library in Bancroft Rd for many years. He was always helpful and had an immense knowledge about Tower Hamlets. c.1979

The Rev David Moore from the Bow Mission and Santiago Bell, an exile from Pinochet’s Chile who was a ceramicist and wood carver. He taught David to carve and, on retirement, David built himself a studio and has been carving ever since. This picture was taken at the opening of Bow Single Homeless & Alcoholic Rehabilitation Project and the carving, which was the work of both David and Santiago, depicts the journey of rehabilitation. c.1986

Builders at Oxford House. c.1978

Gasmen at Mile End Place, 1977

Harry Diamond at a beer festival at Stepping Stones Farm Stepney. After I left art school in 1978, I met Harry at Camerawork in Alie St. He was always generous with his knowledge of photography and, after talking to him, I changed the type of film I was using. Harry was famously painted by Lucien Freud standing next to a pot plant, but when I asked Harry what he thought of Lucien, he did not have a high opinion of the great artist. c.1978

Teacher Martin Cale and Bob the School-keeper (an ex-docker) at John Scurr School. c.1978

At Hungerford Bridge, I came across this man in a doorway. He was not yet asleep so I asked if I could take his photo. ‘If you give me a cigarette,’ he said. ‘I only smoke rollups,’ I replied. ‘That’ll do.’ I rolled him a cigarette then took his portrait. c.1978

Paul Rutishauser ran the print workshop in the basement of St George’s Town Hall in Cable St

‘We don’t want to live in Southend’ – Housing demonstration on the steps of the old Town Hall

Kids from Stepping Stones Farm in Stepney c.1980

“Kingsley Hall was a Charles Voysey designed building off Devons Rd, Bow, that had fallen into disrepair and which we were trying to turn into a community centre.”

Kids from Kingsley Hall

In the pub with Geoff Cade and Helen Jefferies (centre and right) who worked at Kingsley Hall

“Geoffrey Cade worked at Kingsley Hall from about 1982. He fought injustice all his life and was a founding member of Campaign for Police Accountability, a good friend and colleague.”

East London Advertiser reporters strike in Bethnal Green, long before the paper moved to Romford c.1979

National Association of Local Government Officers on strike at the Ocean Estate

Teachers on strike c. 1984

Policing the Teacher’s Strike c. 1984

Teachers of George Green’s School, Isle of Dogs, in support of Ambulance Crews c. 1983

Kevin Courtney was my National Union of Teachers Representative when I began my teaching career

Lollipop Lady in Devons Rd, Bow

“Our first play scheme was in the summer of 1979. One of the workers was a musician called Lesley and her boyfriend was forming a band, so they asked me to photograph them and, as they lived on the Ocean Estate, we went into Mile End Park to do the shoot.”

Does anyone remember the name of this band?

Busker in Cheshire St c. 1979

“We bought our fruit and vegetables every Saturday from John the greengrocer in Globe Rd who did all his business in old money.” c.1980

Photographs copyright © Philip Cunningham

You may also like to take a look at

Joseph Merceron v Ross Poldark

In advance of tonight’s episode of POLDARK, featuring the real life character of Joseph Merceron, Julian Woodford author of THE BOSS OF BETHNAL GREEN, explains how he uncovered the breathtakingly appalling life of this notorious Huguenot, gangster and corrupt East End magistrate.

Joseph Merceron by Joe McLaren

The Cinnamon restaurant is at 134 Brick Lane today but, in 1764, this was a Huguenot pawnbroker’s shop and, on 29th January of that year, a baby boy was born there. His name was Joseph Merceron and he would grow up to be The Boss of Bethnal Green – the Godfather of Regency London.

My biography was a decade in its gestation. I first came across Joseph Merceron’s name in 2005, when I happened upon a reference to him in Roy Porter’s London: A Social History. Porter described Merceron as an early corrupt political ‘Boss’ who had dominated the East End some one hundred and fifty years before it became the home of the Kray twins. By coincidence, I had seen Merceron’s name the day before, listed as a defendant in a series of legal cases at the National Archives. I was intrigued: Merceron is not a common name in England. Was this the same man? The internet confirmed that it was, and revealed that he had been a larger-than-life character. His story seemed to anticipate the plot of the Marlon Brando movie On the Waterfront, where a corrupt gangster is taken on – and eventually toppled – by a brave and determined local priest.

Over the next few days, I found that Merceron was name-checked by virtually every book about the history of London’s darker side, from academic classics like Dorothy George’s London Life in the Eighteenth Century to true-crime exposés like Fergus Linnane’s London’s Underworld. The facts given were always similar, and I soon learned that all these accounts had their origins in The Rule of the Boss, a chapter in Sidney & Beatrice Webb’s seminal 1906 work on English local government, The Parish and the County. The Webbs, a husband-and-wife team of early socialists, were embarking on a nine-volume treatise regarded as a classic by historians. They intended that the centuries of inefficiency and corruption they described would be swept away by the statistical analysis and central planning espoused by the early Labour movement.

The Webbs’ research had unearthed parts of Merceron’s story, seeing him as the perfect illustration of corruption within English parochial self-government. The Marxist academic Harold Laski wrote that ‘they have added new figures to our history, the school books of the next generation will make Merceron [and his like] illuminating examples of what a democracy must avoid.’ As it turned out, Professor Laski was wrong: the Second World War intervened and the prominence given to 20th century history in school curricula meant that Merceron’s story has been largely forgotten.

The Rule of the Boss is an intriguing read, but the Webbs were not biographers, and had no interest in dissecting the personal life behind Merceron’s rule. Their account leaves fundamental questions unanswered. Who exactly was Joseph Merceron? Where did he come from? What drove him? How did he become so wealthy? How did he gain power while so young and retain it for so long? Frustratingly, all subsequent accounts I could find regurgitated parts of the Webbs’ story but failed to provide the answers. Even a brief reference to Merceron in the Dictionary of National Biography could shed no further light. In his excellent book of tales about Brick Lane, An Acre of Barren Ground (2005), Jeremy Gavron had drawn some interesting conclusions about Merceron’s links to the brewer Sampson Hanbury, but when we met Jeremy explained that, apart from this, he too had struggled to make headway with Merceron’s wider story.

Convinced that Merceron’s story was worth telling, I delved deeper. Searching through the births, marriages and deaths columns of The Times, with the help of the electoral register I traced Merceron’s family tree forwards and learned there were just a handful of people with that family name living in the United Kingdom. I wrote to the most promising candidates and a couple of days later was rewarded with a call from an elderly lady who introduced herself as Susan Kendall, Merceron’s great-great-granddaughter. Mrs Kendall added that she would be delighted to invite me to her home in Wiltshire but, she added, ‘You had better come quick, because I’m ninety-three!’

I rushed off to the pretty village of Ramsbury to meet Mrs Kendall and over a cup of coffee explained my plans. But when I mentioned Beatrice Webb, Mrs Kendall almost exploded. ‘That beastly woman,’ she exclaimed, had published Merceron’s story just before her own birth. The Mercerons were a wealthy and respected county family in Edwardian times, and Susan and her sisters were presented at Court to Queen Mary as teenagers. The Webbs’ story had not been helpful, to say the least, and Mrs Kendall expressed satisfaction that finally I was going to disprove it. This was not promising.

When I nervously explained that, based on my research to date, if anything Merceron had been even more of a tyrant than the Webbs had described, I wondered if I was about to be asked to leave. But Mrs Kendall reflected. ‘If that is the true story,’ she said, ‘then of course you must tell it.’ From that moment on, she gave me every support and we corresponded regularly until her death a few years later. She generously lent me the few family papers she had, but said I would need to meet with her nephew Daniel to see the rest.

Daniel Merceron was serving overseas with the army. It was a frustrating several months before he returned and I was able to visit him, but it was worth the wait. Daniel left me with a cup of tea while he disappeared into his attic, returning with Merceron’s two-hundred-year-old tin chest: full of deeds, letters and other papers which shed new light on Merceron’s misdeeds, added colour to his personal life and provided crucial clues to the existence and location of other original records of the Court of Chancery at the National Archives – heavy parchment rolls, encrusted with dust and unopened for two centuries. They told a fascinating story – the depths of an obsession with money which led Merceron to lock away his half-sister in a lunatic asylum and steal the inheritances of his nephews, as well as that of a mentally ill orphaned girl, all before he was twenty-three years old.

But even this was outshone by the other surprise Daniel had in store for me. He disappeared again, returning brandishing an old flintlock pistol that he announced was the weapon with which the madman James Hadfield tried to assassinate King George III at the Drury Lane theatre in 1800. Daniel was unclear how the gun had fallen into Merceron’s hands, but within an hour on the internet we had found the transcript of Hadfield’s trial and discovered that the key prosecution witness, who had picked up the pistol after Hadfield fired it at the King, was none other than Merceron’s clerk.

Pulling this thread further, I uncovered Merceron’s links to a network of government spies, set up to monitor the activities of underground revolutionary societies during the Napoleonic wars. This was the story the Webbs had missed. By keeping Merceron and his associates in power in the East End, successive British governments, desperate to stamp out radical republicanism after the French Revolution, repeatedly turned a blind eye to his criminal operations. In doing so, they abetted a social catastrophe. Joseph Merceron’s story turns out to be more than a tale about a man and his money. It is also about the origins of London’s East End, a world of riots, lynching, public executions and extreme poverty where whole families could easily starve or freeze to death.

As Merceron became extraordinarily wealthy, Bethnal Green became the epitome of the East End Victorian slum. By 1838, when young Charles Dickens chose it as the home of the murderer Bill Sikes in Oliver Twist, Bethnal Green was beset by wretched poverty, the bankrupt home of cholera and typhus, its rotting workhouse crammed with more than a thousand starving paupers.

Joseph Merceron’s name is commemorated today in Merceron St, Bethnal Green, and in Merceron Houses which were erected as ‘model dwellings’ for the poor on the site of Merceron’s garden off Victoria Park Sq, in 1901 just before the Webbs reminded the world of his darker deeds.

Birthplace of Joseph Merceron “On Sunday 29th January 1764, Joseph Merceron was born on Brick Lane, which formed the boundary between the parishes of Spitalfields and its eastward neighbour Bethnal Green. His parents were James Merceron, a Huguenot pawnbroker and former silk weaver, and his second wife Ann. The Mercerons had three other children: Annie, Joseph’s two-year-old sister, John, almost thirteen, and Catherine, eight, the latter two being the surviving offspring from James’s first marriage.”

“Joseph was christened at the local Huguenot church known as La Patente, in Brown’s Lane (the building and lane are now known as Hanbury Hall and Hanbury Street) just a short walk from his parents’ house. The Mercerons, like other Huguenot families in the area, clung tightly to their nationality. Joseph’s details in the register of baptisms – the first recorded at La Patente for 1764 – were entered in French, which many families still insisted on speaking out of respect for their ancestors.”

“On the corner of Fournier Street stands the Jamme Masjid, since 1976 one of London’s largest mosques. For much of the twentieth century it was a synagogue, and before that it spent a decade as a Methodist chapel. Originally, before a brief occupation by the London Society for Promoting Christianity amongst the Jews, it was a Huguenot church. High on a wall is the date of its completion, 1743, and a sundial with its motto: Umbra Sumus (‘we are shadows’).”

“The Merceron pawnshop at 77 Brick Lane was at the epicentre of this district, among a row of ramshackle buildings directly opposite Sir Benjamin Truman’s imposing and famous Black Eagle brewery. The Black Eagle was one of the largest breweries in the world. To those living opposite, the mingled odours of yeast, malt and spilt beer – not to mention the steaming output of the many dray horses – must have been overpowering, even by the pungent standards of the times. The noise, too, was tremendous, as the shouts of draymen punctuated the rumble of horse-drawn carriages and carts up and down the lane.”

“The judge had ordered the execution to take place several miles away at Tyburn, the usual site of such events in London, but the master weavers – keen to dispose of Valline and Doyle in front of their own community to discourage further loom cutting – lobbied successfully to change the location to ‘the most convenient place near Bethnal Green church’. Several thousand people assembled outside The Salmon & Ball to see Valline and Doyle hang. Bricks and stones were thrown during the assembly of the gallows. They protested their innocence to the end, but to no effect. Doyle’s last words were enough to ignite an already explosive situation. As soon as the hanging was over, the crowd tore down the gallows and surged back to Spitalfields…”

“On 26th October 1795, Joseph Merceron donned his magistrate’s wig and robes and climbed the steps of the imposing Sessions House on Clerkenwell Green for his first Middlesex Sessions meeting. This was a world away from Brick Lane. The Sessions House, built in the aftermath of the Gordon Riots, was awe-inspiring and was said to rival any courthouse in England.”

“St John on Bethnal Green was built by the eminent architect Sir John Soane but budgetary constraints led to his grand design for a steeple being aborted, replaced with a stunted tower of particularly phallic design that rapidly became a source of bawdy amusement throughout the neighbourhood. Merceron was outraged. Announcing that the design had ‘mortified and disappointed the expectations of almost every individual’, he ordered Brutton to write to complain. The task put Brutton in an acutely awkward position: how to explain the exact nature of the problem? The vestry clerk’s literary skills were tested to the limit as he described the tower’s ‘abrupt termination in point of altitude’ that made it ‘an object of low wit and vulgar abuse’.”

“All the great and good of London’s East End were there. Twenty thousand people, packed six deep in places along the Bethnal Green Road, had turned out to see the cortège on its way to St Matthew’s church. Just before one o’clock the procession arrived, at a sedate walking pace. The jet-black horses, with their sable plumes, were blinkered to prevent anything from distracting the stately progress of the hearse. Merceron was the original ‘Boss’ of Bethnal Green, the Godfather of Regency London, controlling its East End underworld long before celebrity mobsters such as the infamous Kray twins made it their territory. His funeral at the church of St Matthew, Bethnal Green – the very same church where the Krays’ funerals would be held more than 150 years later – reflected his importance: it was by far the biggest event to take place at the church since it was established in the 1740s.”

Tomb of Peter Renvoize “His closest ally and childhood friend, Peter Renvoize, was repeatedly elected as churchwarden for much of this period, from which position he helped Merceron pull off his most audacious financial coup yet. Bethnal Green’s share of the government relief grant was £12,200, equivalent to almost three times the annual poor’s rates raised by the parish. Having obtained the money, Merceron appointed himself chairman of a committee, with four of his closest associates, including Renvoize, to manage its distribution. What happened next is difficult to determine. But it is clear that, five months after the government had advanced the funds, there were several thousand pounds sitting in Merceron’s own account.”

“As for Joseph Merceron, lying buried in the shadow of the vestry room he dominated for half a century, there is one last strange episode to recount. In the afternoon sunshine of Saturday 7th September, 1940, as millions of Londoners sat down to their tea, the ‘Blitz’ began. Bethnal Green suffered terribly, and in the carnage St Matthew’s church took a direct hit from an incendiary bomb. Next morning it was a roofless, burnt out shell, but two gravestones survived the bombing intact. The first, outside the main entrance to the church, is that of Merceron’s old friend Peter Renvoize. About twenty paces away, a large pink granite slab, surrounded by a low iron rail in the shelter of the south wall of the church, is the grave of Joseph Merceron and his family. He spent a lifetime cheating the law, somehow it is fitting that he should have cheated the Luftwaffe too.”

“Merceron Houses, erected in 1901 by the East End Dwellings Company on land formerly part of Joseph Merceron’s garden in Bethnal Green.”

Joseph Merceron’s signature

The pistol used in the assassination attempt upon George III at Drury Lane in 1800

[youtube iznWirIaqB0 nolink]

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A COPY OF THE BOSS OF BETHNAL GREEN FOR £20

At Ben Truman’s House

Behold the shadows glimmering in this old house in Princelet St built in the seventeen-twenties for Benjamin Truman. A hundred years later, a huge factory was added on the back which more than doubled the size. In the twentieth century, this became the home of the extended Gernstein family who left the house in the eighties. Notable as Lionel Bart’s childhood home, who once returned to have his portrait taken by Lord Snowden on the doorstep, in recent years it has served as the location for innumerable film and photo shoots. Then, as if to complete the circle, the house was acquired by the proprietors of the Old Truman Brewery.

You may also like to take a look at

The Spitalfields Roman Woman

Curator of Human Osteology, Rebecca Redfern watches over her charge

In his Survey of London 1589, John Stow wrote about the discovery of pots of Roman gold coins buried in Spitalfields and it had long been understood that ancient tombs once lined the road approaching London, just as they did along the Appian Way in Rome. Yet it was only in the nineteen-nineties, when large scale excavations took place prior to the redevelopment of the Spitalfields Market, that the full extent of the Roman cemetery was uncovered.

In March 1999, a Roman stone sarcophagus containing a rare lead coffin decorated with scallop shells came to light, indicating the burial of someone of great wealth and high status. Grave goods of fine glass and jet were buried between the coffin and the sarcophagus. It was the first unopened sarcophagus to be found in London for over a century and when the entire assemblage was removed to the Museum of London, the coffin was opened to reveal the body of a young woman in her early twenties, buried in ceremonial fashion. In the week after the opening of the coffin, ten thousand Londoners came to pay their respects to the Spitalfields Roman woman. She was the most astonishing discovery of the excavations yet, as the years have passed and more has been learnt about her, the enigma of her identity has become the subject of increasing fascination.

Analysis of residue in the coffin revealed that her head lay upon a pillow of bay leaves, her body was embalmed with oils from the Arab world and the Mediterranean, and wrapped in silk which had been interwoven with fine gold thread. Traces of Tyrian purple were also found, perhaps from a blanket laid over the coffin. Such an elaborate presentation suggests she may have been displayed to her family and friends seventeen hundred years ago as part of funeral rites.

The sarcophagus and grave goods are on public exhibition at the Museum but, thanks to Rebecca Redfern, Curator of Human Osteology, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie and I had the privilege to visit the Rotunda where the human remains are stored and view the skeleton of the Spitalfields Roman woman. Deep in a windowless concrete bunker filled with metal shelving stacked with cardboard boxes, containing the remains of thousands of Londoners from the past, lay the bones of the woman. We stood in silent reverence with just the sound of distant traffic echoing.

Rebecca is the informal guardian of the Spitalfields woman and remembers switching on the television to watch news of the discovery as a student. Today, she has a four-year-old daughter of her own. “The work went on for so many years that a lot of couples met working in Spitalfields,” Rebecca admitted to me, “and there is now a whole generation of ‘Spital babies’ born to those archaeologists.”

“She’s five foot three and delicately built, petite like a ballet dancer,” Rebecca continued, turning her attention swiftly from the living to the dead and gesturing protectively to the bones laid out upon the table. While some might objectify the skeleton as a specimen, Rebecca relates to the Spitalfields Roman woman and all the other twenty thousand remains in her care as human beings. “They’re able to tell us so much about themselves, it’s impossible not to regard them as people,” she assured me.

Recent research into the isotopes present in the teeth of the Spitalfields Roman woman have revealed an exact match with those found in Imperial Rome, which means that her origin can be traced not just to Italy but to Rome itself. “I find it very sad that she came so far and then died so young,” Rebecca confided, recognising the lack of any indication of the cause of death or whether the woman had given birth. Contemplating the presence of the skeleton with its delicate bones dyed brown by lead, it is apparent that the Spitalfields Roman woman holds her secrets and has many stories yet to tell.

More than seventy-five Roman burials were uncovered at the same time as the sarcophagus, many interred within wooden coffins and some only in shrouds. You might say these represented the earliest wave of immigration to arrive in Spitalfields.

“People were so mobile,” Rebecca explained to me, “We found a fourteen-year-old girl from North Africa whose mother was European. A legion from North Africa was sent to guard Hadrian’s Wall and we have found tagine cooking pots that may been theirs. I pity those men – how they must have suffered in the cold.”

The only Roman sarcophagus discovered in London in our time was uncovered in Spitalfields in 1999

Inside the stone sarcophagus an elaborately decorated lead coffin was discovered

At the Museum of London, the debris was removed to uncover the pattern of scallop shells

The lead coffin was opened to reveal the body of a young woman

Photographs of coffin & excavations copyright © Museum of London

Portrait of Rebecca Redfern & photographs of skeletal details copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

The Animals Of Georgian London

Tom Almeroth Williams introduces CITY OF BEASTS, How Animals Shaped Georgian London

Old Smithfield Market by Jacques-Laurent Agasse, 1824 (courtesy of Yale Centre for British Art)

My ancestor, Herman Almeroth, emigrated to London from Germany in the late eighteenth century and established a sugar refinery in Whitechapel. As a teenager, I grew obsessed with Herman and my fascination with the working world of Georgian London began with him. Yet the catalyst for CITY OF BEASTS was a surprise encounter early one morning with thirty army horses in Kentish Town. When I searched for historical evidence of Georgian London’s animals, I was surprised to find that historians have written so little about horses, cows, sheep, pigs and dogs – the city’s most useful animals.

Herman does not appear in my book – his surviving records do not offer the excuse I require – but he almost certainly kept a cart horse and a guard dog, both of which are featured. My interest is in the relationship between working Londoners and their animals. I do not shy away from animal cruelty but, rather than depicting animals as victims, I explore what they contributed and how their existence was interwoven with human lives.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, an estimated 31,000 horses (double that if you include riding and carriage horses) were at work in the capital. Around the same number of sheep and cattle were driven through the streets every week. No other city in Europe or North America has ever accommodated so many large four-legged animals or felt their influence so profoundly.

The Georgian city of beasts was remarkable because of the astonishing diversity of the interactions between humans and animals. The world’s largest livestock trade was embedded at the heart of the city and both pig-keeping and cow-keeping thrived. While Victorian London employed more draught horses, its Georgian predecessor relied on mill horses to power machinery. In this earlier era, London was the centre of Britain’s equestrian culture, offering park riding and riding houses, as well as hunts and racecourses, before this was lost in the mid-nineteenth century.

Let us take a ride into the Georgian East End. We are setting out from Marylebone in the seventeen-eighties. Terraced houses are covering up fields where dairy cows once grazed. These animals are a vanishing sight in this part of town (where renting pasture is becoming too expensive) and multiplying in less wealthy, more urbanised areas such as Whitechapel and Bethnal Green.

Increasingly, these animals were kept in yards and fed on grain, hay and vegetables. Across Britain, cow-keepers experimented with feeding regimes designed to boost milk and meat yields. In London, a distinctly urban solution was found in the city’s colossal alcohol industry. After extracting liquid wort from grains, brewers and distillers sold their industrial waste – ‘spent grain’ – to local cow-keepers. In the early eighteen-hundreds, William Clement was purchasing grain from Charrington’s Brewery in Mile End and hired carters to make regular deliveries to his yard on the Hackney Rd. Smaller cow-keepers could not afford these cartage costs so they clustered around breweries, distilleries and associated businesses. In 1782, for example, the Gazetteer advertised the sale of a plot in Bethnal Green where the ‘farmer and cow-keeper’ Pearce Dunn kept cows on premises which he shared with a dealer in yeast and stale beer. In common with many other operators, Dunn also maintained a pigsty, recycling the protein-rich whey from his herd’s milk.

The Minories, Whitechapel, Mile End and Stepney housed many of the pigs kept in Georgian London. Although we have come to associate urban sties with poverty and disease, pig-keeping offered a profitable and relatively respectable side-line for entrepreneurial Londoners. In 1776, the Whitechapel distiller Samuel Liptrap contracted with the Navy (which had victualling yards at Tower Hill and Deptford) for £8,200 to supply two thousand hogs, which he delivered in six batches of around three hundred animals.

The East End teemed with inns, taverns, chop houses, pie shops and bakeries, and each of these businesses provided an opportunity for pigs to serve as live recycling plants. In the seventeen-nineties, you find the keepers of a chandler’s shop in East Smithfield and a ‘cook-shop’ in Brick Lane each fattening four pigs. Meanwhile, many victuallers took advantage of substantial yards to erect sties and fed their animals with stale beer and scraps. We know this because these well-fed pigs attracted so much unwanted attention – in 1794, William Goodall of the Ram Inn, West Smithfield, apprehended a man stealing a pregnant sow which, as he proudly informed the Old Bailey, he had bred himself.

To accelerate our progress from Marylebone, we have joined the New Rd or, as you may know it, the Euston Rd. Apologies for the stench and dust – the Paddington to Islington New Rd was created in the 1750s as a bypass to divert livestock droves and waggons out of the West End and Holborn. We have just overtaken a large drove of rather tired black cattle who have walked all the way from Devon to be sold at Smithfield Market.

Located just outside the City walls, Smithfield has been in use as a suburban cattle market since 950 AD. In 1300, it was set in open countryside but, by 1700, it lay at the heart of a heavily populated commercial district. In the Georgian period, the sale of bullocks, sheep, lambs, calves and hogs took place on Mondays and Fridays. By 1822, the market was processing an astonishing 1.7 million animals per year (1,507,096 sheep, 149,885 cattle, 24,609 calves and 20,020 pigs), all transported on the hoof through the city. Cattle sales at Smithfield only reached their peak of 277,000 in 1853, just two years before the trade was moved to Islington.

London’s expansion not only increased demand for meat, it meant livestock had to be driven greater distances through more congested streets. On the night preceding market day, cattle and sheep were collected from suburban pens which encircled the metropolis. From outposts at Islington, Holloway, Mile End, Knightsbridge, Paddington and Newington, drovers converged on the city like swarm. Once their charges were sold, drovers led some animals directly to Smithfield’s slaughterhouses but many more beasts were forced to walk as far as St James’s to meet their demise.

The Smithfield trade inflicted suffering on Londoners as well as their animals. Cattle regularly tossed, gored and trampled people in the streets, leaving them with broken ribs and limbs, fractured skulls, severe bruising and deep puncture wounds. In October 1820, the London Chronicle reported that a bullock running down the Minories from Whitechapel had charged at several women stallholders, leaving them badly injured. Then the enraged animal ran through a court into Rosemary Lane, where it plunged its horns into a cart horse’s belly. Finally, as the horse fell backwards, a porter was crushed to death.

In spite of this chaos, Smithfield remained an economic powerhouse and an awe-inspiring showcase of Britain’s agricultural progress. Its profitability and close relationship with neighbouring banks, inns and other businesses explain why it has resisted attempts to remove it for so long.

Weary of the New Rd, we turn south into Islington passing the fields and barns of some of the city’s most successful dairy farmers, Charles Laycock among them. Keen to avoid Smithfield’s droves and Holborn’s waggon traffic, we turn east to join Old St. One of London’s most frenetic and pungent industrial zones extends between here and Whitechapel, including breweries to paint manufacturers, both of which rely on horse-powered machinery.

By the eighteen-twenties, there were at least forty-two ‘colour-makers’ trading in the capital, mostly in Old St, Whitechapel and Southwark. The eighteenth century witnessed an explosion in the market for house paint, driven by metropolitan building booms and a growing taste for multi-coloured interiors. By the seventeen-forties, some manufacturers were using horse mills to grind up minerals, plants, shells and bone to extract pigments. Substituting horses for human hands saved huge amounts of money which vendors passed on to consumers. This was the origin of Britain’s do-it-yourself culture. London’s paint manufacturers rendered many house painters redundant because their pigments could be mixed with oil at home and applied by a servant. Some became big businesses in the same league as brewers, London’s leading industrialists.

Traditionally, brewing’s most energy-intensive processes – grinding malt, pumping water and drawing liquid wort from the mash ton into the copper – had been powered by man power as well as horse power. This all changed in the first half of the eighteenth century when breweries installed mill wheels driven by horses which, when linked to a gearing system, enabled them to mill and pump simultaneously. By increasing efficiency and cutting the cost of human labour, mill horses facilitated a revolution in brewing. Brewers had to expand their haulage operations to deliver beer to the pubs which were springing up across an expanding metropolis. It was for this reason that the Black Eagle’s dray horse stable almost doubled from 57 to 103 between 1810 and 1835.

These were some of the finest heavy horses in the country, admired for their strength and stamina but also for their intelligence. Visitors to the capital were astonished to observe that dray horses could raise and lower barrels without instruction. These animals were worked extremely hard. In 1764, a brewer in Hackney confirmed that his stables were never locked ‘because we are fetching the horses out almost all hours of the night’. Although this created suffering, equally brewing was at the forefront of improvements in horse breeding, stabling, feeding and farriery. In 1837, Truman’s unveiled a state-of-the-art stable for one hundred and fourteen, costing almost the same as Lambeth’s Church of St Andrew.

Virtually every business relied on cart horses, not least London’s construction trades. One of the most important in the East End was brick-making. In this period, bricks were made using horse-powered pugging mills and transported to building sites in carts. As an Old Bailey trial from 1809 reveals, this created heavy work for both men and horses.

On 20th September, Benjamin Hall set off from a brickmaker’s yard at Whitechapel Mount with a horse and cart crammed with five hundred bricks. After unloading at Wentworth Street in Spitalfields, the co-workers delivered a thousand bricks in two outings to the Swan Tavern in Bethnal Green. By then, Hall’s horse had hauled more than four tons of bricks over a total distance of eleven kilometres and this only amounted to half a day’s work. In the afternoon, the pair headed to Truman’s with another load. Hall claimed that, on arrival, he left his horse and cart in the care of a boy, went for a beer, and when he returned the bricks had gone. Hall was publicly whipped though Whitechapel and put to hard labour for six months. We cannot be sure of his guilt but carters lived tough lives, so I would not put it past or hold it against him.

Hurrying to catch a train a few weeks ago, I ended up retracing part of Hall’s fateful delivery route. I cannot walk anywhere in London now without thinking about what animal-related activity took place there. The survival of Georgian and Victorian architecture obviously makes this imaginative leap easier and more thrilling which is why I feel the loss when buildings like Tadmans on Jubilee St are destroyed. My ancestor’s sugar refinery has been gone for much longer but I still visit where it used to be and try, in vain, to picture it.

I hope my book offers new insights into the lives of Georgian Londoners and the workings and character of their city. I have found that even the most utilitarian old buildings, including stables and workshops, have extraordinary stories to tell.

The Second Stage of Cruelty by William Hogarth, 1751 (courtesy of Yale Centre for British Art)

(click on image to enlarge) The London Hospital Whitechapel, seen from the northern side of Whitechapel Rd, showing dozens of cattle being goaded by drovers, surrounded by waggons, carriages, riders and pedestrians. c. 1753 (courtesy of the Wellcome Collection)

Smithfield Drover from Pyne’s Costume of Great Britain, 1804 (courtesy of Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

Brick maker from Pyne’s Costume of Great Britain, 1804 (courtesy of Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

Truman’s dray horses in the twentieth century (courtesy of Truman’s Beer)

Geoffrey Fletcher’s drawing of Tadmans from ‘The London Nobody Knows,’ 1962 shows a horse-drawn funeral hearse

Click here to order a copy of Thomas Almeroth Williams’ CITY OF BEASTS

You may also like to read about

In Search Of Culpeper’s Spitalfields

Ragwort in Hanbury St

(The concoction of the herb is good to wash the mouth, and also against the quinsy and the king’s evil)

Taking the opportunity to view the plaque upon the hairdresser at the corner of Puma Court and Commercial St, commemorating where Nicholas Culpeper lived and wrote The English Herbal, the celebrated seventeenth century Herbalist returned to his old neighbourhood for a visit and I was designated to be his guide.

Naturally, he was a little disoriented by the changes that time has wrought to Red Lion Fields where he once cultivated herbs and gathered wild plants for his remedies. Disinterested in new developments, instead he implored me to show him what wild plants were left and thus we set out together upon a strange quest, seeking weeds that have survived the urbanisation. You might say we were searching for the fields in Spitalfields since these were plants that were here before everything else.

Let me admit, I did feel a responsibility not to disappoint the old man, as we searched the barren streets around his former garden. But I discovered he was more astonished that anything at all had survived and thus I photographed the hardy specimens we found as a record, published below with Culpeper’s own annotations.

Honeysuckle in Buxton St (I know of no better cure for asthma than this, besides it takes away the evil of the spleen, provokes urine, procures speedy delivery of women in travail, helps cramps, convulsions and palsies and whatsoever griefs come of cold or stopping.)

Dandelion in Fournier St (Vulgarly called Piss-a-beds, very effective for obstructions of the liver, gall and spleen, powerful cleans imposthumes. Effectual to drink in pestilential fevers and to wash the sores. The juice is good to be applied to freckles, pimples and spots.)

Campion in Bishop’s Sq (Purges the body of choleric humours and helps those that are stung by Scorpions and other venomous beasts and may be as effectual for the plague.)

Pellitory of the Wall in Hanbury St (For an old or dry cough, the shortness of breath, and wheezing in the throat. Wonderfully helps stoppings of the urine.)

Herb Robert in Folgate St (Commended not only against the stone, but to stay blood, where or howsoever flowing, and it speedily heals all green wounds and is effectual in old ulcers in the privy parts.)

Sow Thistle in Princelet St (Stops fluxes, bleeding, takes away cold swellings and eases the pains of the teeth)

Groundsel off Brick Lane (Represses the heat caused by motions of the internal parts in purges and vomits, expels gravel in the veins or kidneys, helps also against the sciatica, griping of the belly, the colic, defects of the liver and provokes women’s courses.)

Ferns and Campanula and in Elder St (Ferns eaten purge the body of choleric and waterish humours that trouble the stomach. The smoke thereof drives away serpents, gnats and other noisome creatures which in fenny countries do trouble and molest people lying their beds.)

Sow Thistle and Herb Robert in Elder St

Yellow Wood Sorrel and Sow Thistle in Puma Court (The roots of Sorrel are held to be profitable against the jaundice.)

Comfrey in Code St (Helps those that spit blood or make a bloody urine, being outwardly applied is specially good for ruptures and broken bones, and to be applied to women’s breasts that grow sore by the abundance of milk coming into them.)

Sow Thistle in Fournier St

Field Poppy in Allen Gardens (A syrup is given with very good effect to those that have the pleurisy and is effectual in hot agues, frenzies and other inflammations either inward or outward.)

Fleabane at Victoria Cottages (Very good to heal the nipples and sore breasts of women.)

Sage and Wild Strawberries in Commercial St (The juice of Sage drank hath been of good use at time of plagues and it is commended against the stitch and pains coming of wind. Strawberries are excellent to cool the liver, the blood and the spleen, or an hot choleric stomach, to refresh and comfort the fainting spirits and quench thirst.)

Hairy Bittercress in Fournier St (Powerful against the scurvy and to cleanse the blood and humours, very good for those that are dull or drowsy.)

Oxe Eye Daisies in Allen Gardens (The leaves bruised and applied reduce swellings, and a decoction thereof, with wall-wort and agrimony, and places fomented or bathed therewith warm, giveth great ease in palsy, sciatica or gout. An ointment made thereof heals all wounds that have inflammation about them.)

Herb Robert in Fournier St

Camomile in Commercial St (Profitable for all sorts of agues, melancholy and inflammation of the bowels, takes away weariness, eases pains, comforts the sinews, and mollifies all swellings.)

Unidentified herb in Commercial St

Buddleia in Toynbee St (Aids in the treatment of gonorrhea, hepatitis and hernia by reducing the fragility of skin and small intestine’s blood vessel.)

Hedge Mustard in Fleur de Lys St (Good for all diseases of the chest and lungs, hoarseness of voice, and for all other coughs, wheezing and shortness of breath.)

Buttercup at Spitalfields City Farm (A tincture with spirit of wine will cure shingles very expeditiously, both the outbreak of small watery pimples clustered together at the side, and the accompanying sharp pains between the ribs. Also this tincture will promptly relieve neuralgic side ache, and pleurisy which is of a passive sort.)

You may like to read about

Wonderful London’s East End

It is my pleasure to publish these evocative pictures of the East End (with some occasionally facetious original captions) selected from the popular magazine Wonderful London edited by St John Adcock and produced by The Fleetway House in the nineteen-twenties. Most photographers were not credited – though many were distinguished talents of the day, including East End photographer William Whiffin (1879-1957).

Boys are often seen without boots or stockings, and football barefoot under such conditions has grave risks from glass or old tin cans, but there are many urchins who would rather run about barefoot.

When this narrow little dwelling in St John’s Hill, Shadwell, was first built in 1753, its inhabitants could walk in a few minutes to the meadows round Stepney or, venture further afield, to hear the cuckoo in the orchards of Poplar.

Middlesex St is still known by its old name of Petticoat Lane. Some of the goods on offer at amazingly low prices on a Sunday morning are not above suspicion of being stolen, and you may buy a watch at one end of the street and see it for sale again by the time you reach reach the other.

A vanished theatre on the borders of Hoxton, just before demolition, photographed by William Whiffin. In 1838, a tea garden by the name of ‘the Eagle Tavern’ was put up in Shepherdess Walk in the City Rd near the ‘Shepherd & Shepherdess,’ a similar establishment founded at the beginning of the same century. Melodramas such as ‘The Lights ‘O London’ and entertainments like ‘The Secrets of the Harem,’ were also given. In 1882, General Booth turned the place into a Meeting Hall for his Salvation Army. There is little suggestion of the pastoral about Shepherdess Walk now.

In the East End and all over the poorer parts of London, a strange kind of establishment, half booth, half shop, is common and particularly popular with greengrocers. Old packing cases are the foundation of a slope of fruit which begins unpleasantly near the level of the pavement and ends in the recess behind the dingy awning. At night, the buttresses of vegetables are withdrawn into shelter.

Old shop front in Bow photographed by William Whiffin. Pawnbroking, once as decorous as banking, has fallen from the high estate in the vicinity of Lombard St. Now, combined instead with the sale of secondhand jewellery, furniture and hundred other commodities, it is apt to seek the corners of the meaner streets.

A water tank covered by a plank in a backyard among the slums is an unlikely place for a stage, but an undaunted admirer of that great Cockney humorist, Charlie Chaplin, is holding his audience with an imitation of the well-known gestures with which the famous comic actor indicates the care-free-though-down-and-out view of life which he has immortalised.

Old shop front in Poplar photographed by William Whiffin

An old charity school for girl and boy down at Wapping founded in 1704. The present building dates from 1760 and the school is supported by voluntary subscriptions. The school provided for the ‘putting out of apprentices’ and for clothing the pupils.

The hunt for bargains in Shoreditch. A glamour surrounds the rickety coster’s barrow which supports a few dozens of books. But, to tell the truth, the organisation of the big shops is now so efficient that the chances of finding anything good at these open air book markets may have long odds laid against it.

The landsman’s conception of a sailing vessel, with all its complex of standing and running rigging that serves mast and sail with ordered efficiency, is apt for a shock when he sees a Thames barge by a dockside. The endless coils and loops of rope of different thickness, the length of chain and the litter of brooms, buckets, fenders and pieces of canvas, seem to be in the most insuperable confusion.

Gloom and grime in Chinatown. Pennyfields runs from West India Dock Rd to Poplar High St. A Chinese restaurant on the corner and a few Chinese and European clothes are all that is to be seen in the daytime.

The gem of Cornhill, Birches, where it stood for two hundred years. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the brothers Adam erected its beautiful shop front. Within were old bills of fare printed on satin, a silver tureen fashioned to the likeness of a turtle and many other curious odd-flavoured things. Birches have catered for the inspired feasting of the City Companies and Guilds for two centuries but now this shop has moved to Old Broad St and, instead of Adam, we are to have Art Nouveau ferro-concrete.

It is doubtful if the Borough Council of Poplar had any notion, when they supplied the district with water carts, that the supplementary use pictured in this photograph by William Whiffin would be made of them. Given a complacent driver, there is no reason why these children should not go on for miles.

Grime and gloom in St George’s St photographed by William Whiffin. St George’s St used to be the famous Ratcliff Highway and runs from East Smithfield to Shadwell High St. It is a maritime street and contains various establishments, religious and otherwise, which cater for the sailor.

River Lea at Bow Bridge photographed by William Whiffin. On the right are Bow flour mills, while to the left, beyond the bridge, a large brewery is seen.

A view of Curtain Rd photographed by William Whiffin, famed for its cabinet makers. It runs from Worship St – a turning to the left when walking along Norton Folgate towards Shoreditch High St – to Old St. Curtain Rd got its name from a curtain wall, once part of the outworks of the city’s fortifications.

Fish porters of Billingsgate gathered around consignments lately arrived from the coast. At one time, smacks brought all the fish sold in the market and were unloaded at Billingsgate Wharf, said to be the oldest in London.

Crosby Hall as it stood in Bishopsgate. Alderman Sir John Crosby, a wealthy grocer, got the lease of some ground off Bishopsgate in 1466 from Alice Ashfield, Prioress of St Helen’s, at a rent of eleven pounds, six shillings and eightpence per annum, and built Crosby Hall there. It came into the possession of Sir Thomas More around 1518 and by 1638 it was in the hands of the East India Company, but in 1910 it was taken down and re-erected in Cheyne Walk.

Whatever their relations with the Constable may come to be in later life, the children of the East End, in their early days, are quite willing to use his protection at wide street crossings.

There is no more important work in the great cities than the amelioration of the slum child’s lot. Many East End children have never been beyond their own disease-ridden courts and dingy streets that form their playground.

Photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

![[Detail of] The London Hospital Whitechapel_seen from the northern side of the Whitechapel Road_c1753_Wellcome Collection CC BY](https://i0.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Detail-of-The-London-Hospital-Whitechapel_seen-from-the-northern-side-of-the-Whitechapel-Road_c1753_Wellcome-Collection-CC-BY-600x275.jpg?resize=600%2C275)