East End Mulberry Harvest

Now is the season for Mulberries, as this photograph I took yesterday confirms. We are working with Kitty Travers of the celebrated La Grotta Ices to produce Mulberry ice cream for our campaign to SAVE THE BETHNAL GREEN MULBERRY and we need your help to harvest the Mulberries.

If you have a Mulberry tree or access to one, we would be grateful if you can harvest them for us. If you have a Mulberry tree in the East End and are willing for us to come and harvest them, please get in touch. If you are willing to contribute a few hours harvesting Mulberries in the East End in the next ten days, please get in touch and give details of your availability.

Write to spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

The central collecting point for Mulberries will be Leila’s Shop in Calvert Avenue on the Boundary Estate, Shoreditch. Anyone that supplies Mulberries will receive some of our Mulberry ice cream in recompense.

We will shortly be announcing the next stage in our campaign to SAVE THE BETHNAL GREEN MULBERRY and stop developers Crest Nicholson uprooting the oldest tree in the East End. This week, the Woodland Trust criticised Tower Hamlets Council in the case of the Bethnal Green Mulberry for not enforcing the change in National Planning Policy Framework of July 2018 designed to extend protection to Ancient and Veteran trees.

Aubrey Silkoff At The Boundary Estate

Aubrey Silkoff returned to Navarre St, Arnold Circus, to view the brick where he incised his name on the nineteenth of April 1950, when he was eleven years old. You can see it just to the left of his upper arm in the photo above, indicated by two white dots on the brick.

When I first spoke with Aubrey over the phone, he admitted that he had no memory of carving it, although he confirmed that he grew up in Laleham Buildings on the Boundary Estate and Navarre St was where he played football as a child.

Fortunately for us, 1950 was also the year of the photo craze when Aubrey and his pals acquired cameras and were able develop their pictures at the Boys Club at Virginia Rd School. As a consequence, we have a photographic record to show us some of the children who wrote their names on the wall of Wargrave Buildings at that time. Capturing the spirit and energy of a fleeting moment, these pictures allow us to put faces to the names incised on the bricks, vividly evoking the childhood world of over half a century ago which produced graffiti of such unlikely longevity. Recalling Bert Hardy’s photographs of East End children on the street, what makes these exuberant images special is that they were taken by the children themselves.

As we walked down Navarre St together, I had the strange experience of introducing Aubrey to his long forgotten graffiti. “It was something to do while we talked,” said Aubrey, explaining that he and his pals used nails from the wooden scooters they constructed to roam as far as the bombsites in the City and around St Pauls. Yet although Aubrey recognised a few names when he saw them on the wall and even matched some up to the pictures, together we confronted the limit of his fragmentary memory after so many years. “I wonder what life held for them?” he said quietly, contemplating the names on the wall, as we stood in the empty street lined with parked cars that once echoed to the noise of children playing.

“The streets were clear of vehicles, except maybe the odd coal wagon or a fruiterer with a horse and cart. There were few cars because no-one could afford one and, if someone bought one, they took all the kids for a ride in it as a novelty,” Aubrey told me, explaining how, as children, they had possession of the streets for their playground, using cans, or laying down jumpers or coats in the road, to create goalposts.

“We were a group of kids that used to know each other and spend all our time together in the streets because the flats were not conducive to living in. There was no space for us inside, so we used to be outside, swinging on the railings at the corner of Navarre St and Arnold Circus. We didn’t know anything about girls. The boys had nothing to do with girls. Half the kids were Jewish but there was no conscious decision to mix with your own kind, although I think we gravitated together because we considered ourselves outsiders. Many kids had lost their fathers in the war, and they had background problems.

You didn’t know that you don’t have much money, because it was just not to be found. I had new clothes once a year. I used to have a new suit at Passover. My mother took me down to a place off Brick Lane. There were schleppers everywhere on the street – touts for tailors. I remember going back for fittings, there wasn’t much ready-made clothing available then. I was ashamed of my parents because I was born late and I thought they were old. On the day of the V.E celebrations we came down into the yard with our food on plates and our chipped enamel cups, we didn’t have china. And when the people saw them, they asked in disapproval, ‘Can we replace them?’ That was embarrassing.

I took the eleven-plus exam which decided whether I would go to Grammar School or Secondary Modern which was inferior. I don’t know what happened but I never passed or failed, I went to a Central School instead. At the end of term we were called onto the stage and divided up between which schools we were going to. I cried because I didn’t go to Grammar School. It was cruel because it split friendships up. ‘What are you doing today? We’re doing Latin and logarithmic equations,’ they said, and I felt a failure because I didn’t do any of those things.

Nothing has been easy for me, exams were always hard. But I was never at the bottom and never excelled either, I was always in the heap. I was fortunate that in those post-war years there were expanding opportunities open to me, giving me an education and a career. Because I had no ambition, I never looked further than my nose. Though I knew I wanted to get out of the East End because I did not want to work in a tailoring sweatshop as my father and all his friends did. As a greeting they, always asked each other, “Are you working?” because the work was seasonal and people were out of work for long periods of time.

In 1958, I moved out to a bedsitter in Stoke Newington on my own. I learnt to look out for myself and be wary of what people are trying to put over you, and as a consequence I’ve been known as a cynical person throughout my life. But I have no regrets about any of it today because it gave me a sense of looking at the glass as half-empty. I never expected anything wonderful to happen and it has. I have progressed over the years and I feel very lucky indeed.

I was interested in classical music from a very early age. One day I went over to Sadler’s Wells Theatre and offered money to buy a ticket but the kiosk person said ‘You haven’t got enough’, so this couple behind me in the queue said, ‘Do you really want to see it?’ and they bought me a ticket. That was ‘La Boheme’ – I wish I could repay that couple today.”

Contemplating the photo of himself at eleven, a crucial moment in his childhood, Aubrey pointed out the spilt food on the “scruffy” jacket and interpreted his expression as “sardonic,” while I saw self-possession and humour in his youthful visage. “I’m thinking ‘Why am I here?'” he said, rolling his eyes with a droll grin.

“Now I look at all these photographs and I wonder,’Did it actually happen?'” continued Aubrey, thinking out loud. Yet when he returned to Arnold Circus, he encountered the evidence that it did happen, because nearly seventy years later, Aubrey found his name graven into the wall on Navarre St – Aubrey Silkoff, Wed 19th April 1950.

Aubrey at the time he wrote his name on the wall of Wargrave Buildings

At the photographic club

At Arnold Circus, with the bandstand visible in the background

A stunt at the corner of Navarre St

The trick revealed – this is the same pillarbox

Aubrey Silkoff – with his brick in the top left corner

You may also like to read about

Sylvester Mittee, Welterweight Champion

This interview and photographs were commissioned by Ally Capellino and are published in a booklet entitled BOXERS. Free copies are available from press@allycapellino.co.uk

Sylvester Mittee by Alexander Sturrock

I shall never forget my visit to Sylvester Mittee, unquestionably one of the most charismatic and generous of interviewees. We met in his multicoloured flat in Hackney where Sylvester keeps his collection of hats that he waterproofs by painting with excess gloss paint left over from decorating his walls. During the course of our interview I began to go blind due to a migraine, yet Sylvester cured me by pummelling my back as a form of massage. Thanks to Sylvester’s therapy, I was bruised for weeks afterwards but my migraine was dispelled, and I came away with this remarkable interview.

“666 is my birth number, and my mother got scared until a priest told her that 666 is God’s number. I was called “spirit” back then. My mother, she went to the marketplace a few months before I arrived. She told people she could already feel me kicking and they said, “I think it’s the devil you got in there!”

My father was born in 1906, he was a very sober man and he liked to give beatings. He especially liked to beat me and I learnt to take it. He came to Britain from St Lucia in 1961, he’s passed away now. My mother still lives in St Lucia, she was born in 1926, she’s a tough old girl.

1966, 1976 and 1986 were important years for me, and at school nobody got more sixes than I did. Six is the number of truth and love and enlightenment. The only time I believed six was unlucky was when I was ill and life wasn’t happening for me.

I’ve been fighting for my life since I stepped off that banana boat at Southampton in 1962. Does a banana boat sound primitive? Ours had air-conditioning and a swimming pool.

My dad worked his bollocks off, doing everything he could to keep us alive. At first, he had a place in Hackney, then he rented a little run-down one bedroom flat in Bethnal Green, with my parents in one room and eight kids in the other, two girls and six boys. We had to live very close in them days. I came from St Lucia with my mum and dad in 1962 and my four sisters came in 1964 and my remaining four brothers in 1966.

When I came to England racism was bare. The kids in the playground ganged up on me and outnumbered me and they attacked me. Nobody did anything about it, parents, teachers, nobody. There was etiquette in fighting back home, but there was none of that in England. I was taught that you let people get up and you don’t hit people when they are down. But, if somebody hits you, you hit them back – that’s how I was brought up. I had to learn to fight. And I had to be good at it to survive. I had no choice. I fought to live and boxing became my life.

Before I knew how to reason, boxing was a short cut. The demons that you have inside, they control you unless you can think in a philosophical way. Boxing becomes a microcosm of the world when you are exposed to the extreme highs and lows of this life.

The experiences that boxing gave me have allowed me to grow. I’m like a tree and the punches I throw are the leaves I drop, so boxing is like photosynthesis for me. I fulfill my immediate needs, but I can also recognise my greater needs, and it is a chance to grow stronger.

Boxing is an opportunity to profess your philosophy through your actions and discover who you truly are. We are born into a part in life and expected to play our part bravely, and I am playing my part as good as I can. Boxing taught me how to grasp life. But the achievement is not in the winning, the enterprise will only hurt you if you seek perfection. I was European Welterweight Champion, but I say boxing just helped me get my bearings in life.

The boys in the playground who beat me, they were the ones who bought tickets to see me fight and they were cheering me on, supporting me. It gave me heart. I like to think it changed them, made them better people. I am a youth worker now in Hackney, and I also go to old people’s homes to do fitness classes and mobility exercises. Those kids that fought me in the playground and beat me, they live around me still. Now they are grown up and I work with some of their kids, and they come to me and tell me their parents remember me from school.”

Sylvester Mittee, European Welterweight Champion 1985

Sylvester in his living room

Sylvester on the cover of Boxing New 1985

Photographs copyright © Alexander Sturrock

You may also like to read my interview with

Eleanor Crow’s Shopfronts Of London

Seven years have passed since we first presented Eleanor Crow’s beautiful watercolours of East End shops in these pages and I am delighted to announce that Spitalfields Life Books is now publishing a handsome hardback collection of them SHOPFRONTS OF LONDON, In Praise of Small Neighbourhood Shops in collaboration with Batsford Books.

You can preorder to support publication and you will receive a signed copy in the first week of September. Click here to preorder for £14.99

At a time of momentous change in the high street, Eleanor’s witty and fascinating personal survey champions the enduring culture of Britain’s small neighbourhood shops.

As our high streets decline into generic monotony, we cherish the independent shops and family businesses that enrich our city with their characterful frontages and distinctive typography.

Eleanor’s collection includes more than hundred of her watercolours of the capital’s bakers, cafés, butchers, fishmongers, greengrocers, chemists, launderettes, hardware stores, eel & pie shops, bookshops and stationers. Her pictures are accompanied by the stories of the shops, their history and their shopkeepers – stretching from Chelsea in the west to Bethnal Green and Walthamstow in the east.

We guarantee you will recognise many of the shops in Eleanor’s book and we publish a selection of her favourite ironmongers below.

Eleanor Crow at E. Pellicci by Colin O’Brien

Daniel Lewis & Son Ltd, Hackney Rd

C W Tyzack, Kingsland Rd

Bernardes Trading Ltd, Barking Rd

Bradbury’s, Broadway Market

Chas Tapp, Southgate Rd

Emjay Decor, Bethnal Green Rd

General Woodwork Supplies, Stoke Newington High St

Diamond Ladder Factory, Lea Bridge Rd

Farringdon Tool Supplies, Exmouth Market

Histohome, Stoke Newington High St

KAC Hardware, Church St

Leyland SDM, Balls Pond Rd

KTS the Corner, Kingsland Rd

Mix Hardware, Blackstock Rd

City Hardware, Goswell Rd

Travis Perkins, Kingsland Rd

SX, Essex Rd

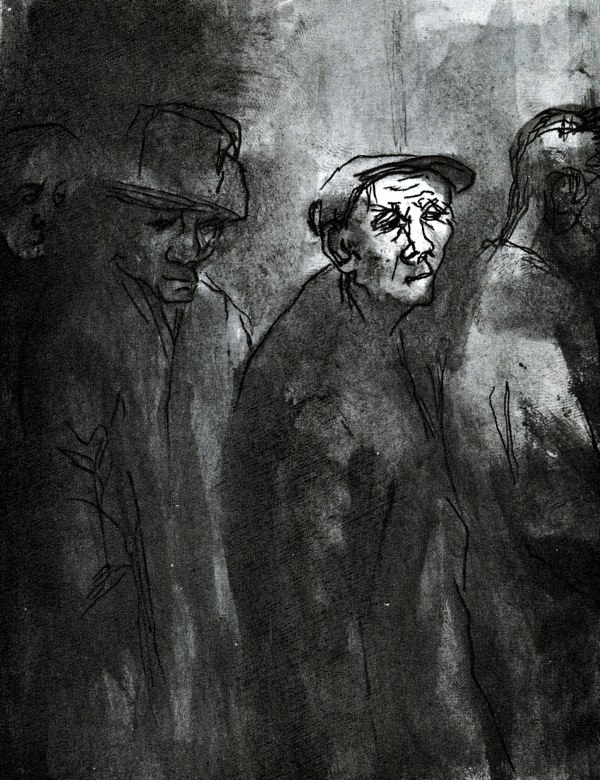

Eva Frankfurther’s Drawings

There is an unmistakeable melancholic beauty which characterises Eva Frankfurther‘s East End drawings made during her brief working career in the nineteen-fifties. Born into a cultured Jewish family in Berlin in 1930, she escaped to London with her parents in 1939 and studied at St Martin’s School of Art between 1946 and 1952, where she was a contemporary of Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach.

Yet Eva turned her back on the art school scene and moved to Whitechapel, taking menial jobs at Lyons Corner House and then at a sugar refinery, immersing herself in the community she found there. Taking inspiration from Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz and Picasso, Eva set out to portray the lives of working people with compassion and dignity.

In 1958, afflicted with depression, Eva took her own life aged just twenty-eight, but despite the brevity of her career she revealed a significant talent and a perceptive eye for the soulful quality of her fellow East Enders.

“West Indian, Irish, Cypriot and Pakistani immigrants, English whom the Welfare State had passed by, these were the people amongst whom I lived and made some of my best friends. My colleagues and teachers were painters concerned with form and colour, while to me these were only means to an end – the understanding of and commenting on people.” – Eva Frankfurther

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also wish to take a look at

The Consolation of Schrodinger

I believe most will agree that life is far from easy and that dark moments are an inescapable part of human existence. When I feel sad, when I feel confused, when I feel conflicted, when it all gets too much and my head is crowded with thoughts yet I do not even know what to do next, I lie down on my bed to calm myself.

On such an occasion recently, I was lying in a reverie and my consciousness was merging with the patterns of the changing light on the ceiling, when I heard small footsteps enter the room followed by a soft clump as Schrodinger landed upon the coverlet in a leap.

I lifted my head for a moment and cast my eyes towards him and he looked at me askance, our eyes meeting briefly in the half-light of the shaded room before I lay my head back and he settled himself down at a distance to rest.

I resumed my contemplation, trying to navigating the shifting currents of troubling thoughts as they coursed through my head but drifting inescapably into emotional confusion. Suddenly my mind was stilled and halted by the interruption of the smallest sensation, as insignificant yet as arresting as a single star in a night sky.

Turning my head towards Schrodinger, I saw that he had stretched out a front leg to its greatest extent and the very tip of his white paw was touching my calf, just enough to register. Our eyes met in a moment of mutual recognition that granted me the consolation I had been seeking. I was amazed. It truly was as if he knew, yet I cannot unravel precisely what he knew. I only know that I was released from the troubles and sorrow that were oppressing me.

When he was the church cat, Schrodinger lived a public life and developed a robust personality that enabled him to survive and flourish in his role as mascot in Shoreditch. After over a year living a private domestic life in Spitalfields, he has adapted to a quieter more intimate sequestered existence, becoming more playful and openly affectionate.

At bedtime now, he leaps onto the coverlet, rolling around like a kitten before retreating – once he has wished me goodnight in his own way – to the sofa outside the bedroom door where he spends the night. Thus each day with Schrodinger ends in an expression of mutual delight.

You may also like to read about

Schrodinger’s First Year in Spitalfields

Schrodinger’s First Winter in Spitalfields

Schrodinger, Shoreditch Church Cat

At Dr Johnson’s House

I walked over to Fleet St to pay a visit upon Dr Samuel Johnson who could not resist demonstrating his superlative erudition by recounting examples of lexicography that came to mind as he showed me around the rambling old house in Gough Sq where he wrote his famous Dictionary

House. n.s. [hus, Saxon, huys, Dutch, huse, Scottish.] 1. A place wherein a man lives, a place of human abode. 2. Any place of abode. 3. Place in which religious or studious persons live in common, monastery, college. 4. The manner of living, the table. 5. Family of ancestors, descendants, and kindred, race. 6. A body of parliament, the lords or commons collectively considered.

Acce’ss. n.s. [In some of its senses, it seems derived from accessus, in others, from accessio, Lat. acces, Fr.] 1. The way by which any thing may be approached. 2. The means, or liberty, of approaching either to things or men. 3. Encrease, enlargement, addition. 4. It is sometimes used, after the French, to signify the returns of fits of a distemper, but this sense seems yet scarcely received into our language.

To Rent. v.a. [renter, Fr.] 1. To hold by paying rent. 2. To set to a tenant.

Ba’ckdoor. n.s. [from back and door.] The door behind the house, privy passage.

Door. n.s. [dor, dure, Saxon, dorris, Erse.] The gate of a house, that which opens to yield entrance. Door is used of houses and gates of cities, or publick buildings, except in the licence of poetry.

Hábitable. adj. [habitable, Fr. habitabilis, Lat.] Capable of being dwelt in, capable of sustaining human creatures.

Time. n.s. [ꞇıma, Saxon, tym, Erse.] 1. The measure of duration. 2. Space of time. 3. Interval. 4. Season, proper time.

Stair. n.s. [ꞅꞇæᵹꞃ, Saxon, steghe, Dutch.] Steps by which we rise an ascent from the lower part of a building to the upper. Stair was anciently used for the whole order of steps, but stair now, if it be used at all, signifies, as in Milton, only one flight of steps.

Chair. n.s. [chair, Fr.] 1. A moveable seat. 2. A seat of Justice or authority. 3. A vehicle borne by men, a sedan.

Díctionary. n.s. [dictionarium, Latin.] A book containing the words of any language in alphabetical order, with explanations of their meaning, a lexicon, a vocabulary, a word-book.

A’ftergame. n.s. [from after and game.] The scheme which may be laid, or the expedients which are practised after the original design has miscarried, methods taken after the first turn of affairs.

Mystago’gue. n.s. [μυσταγωγὸς, mystagogus, Latin.] One who interprets divine mysteries, also one who keeps church relicks, and shews them to strangers.

Box. n.s. [box, Sax. buste, Germ.] 1. A case made of wood, or other matter, to hold any thing. It is distinguished from chest, as the less from the greater. It is supposed to have its name from the box wood. 2. The case of the mariners compass. 3. The chest into which money given is put. 4. The seats in the playhouse, where the ladies are placed. (David Garrick’s box illustrated)

Fascina’tion. n.s. [from fascinate.] The power or act of bewitching, enchantment, unseen inexplicable influence.

A’fternoon. n.s. [from after and noon.] The time from the meridian to the evening.

Intelléctual. n.s. Intellect, understanding, mental powers or faculties. This is little in use.

Prívacy. n.s. [from private.] 1. State of being secret, secrecy. 2. Retirement, retreat. 3. [Privauté, Fr.] Privity; joint knowledge; great familiarity. Privacy in this sense is improper. 4. Taciturnity.

Lexicógrapher. n.s. [λεξικὸν and γράφω, lexicographe, French.] A writer of dictionaries, a harmless drudge, that busies himself in tracing the original, and detailing the signification of words.

Ca’binet. n.s. [cabinet, Fr.] 1. A set of boxes or drawers for curiosities, a private box. 2. Any place in which things of value are hidden. 3. A private room in which consultations are held.

A’bsence. n.s. [See Absent.] 1. The state of being absent, opposed to presence. 2. Want of appearance, in the legal sense. 3. Inattention, heedlessness, neglect of the present object.

Work. n.s. [weorc, Saxon, werk, Dutch.] 1. Toil, labour, employment. 2. A state of labour. 3. Bungling attempt. 4. Flowers or embroidery of the needle. 5. Any fabrick or compages of art. 6. Action, feat, deed. 7. Any thing made. 8. Management, treatment. 9. To set on Work To employ, to engage.

Way. n.s. [wœʒ, Saxon, weigh, Dutch.] The road in which one travels.

Court. n.s. [cour, Fr. koert, Dut. curtis, low Latin.] 1. The place where the prince resides, the palace. 2. The hall or chamber where justice is administered. 3. Open space before a house. 4. A small opening inclosed with houses and paved with broad stones.

Cat. n.s. [katz, Teuton. chat, Fr.] A domestick animal that catches mice, commonly reckoned by naturalists the lowest order of the leonine species.

To Mew. v.a. [From the noun miauler Fr.] To cry as a cat.

Visit Dr Johnson’s House, 17 Gough Square, EC4A 3DE

You may also like to read about