James Boswell’s East End

A few years ago, I visited a leafy North London suburb to meet Ruth Boswell – an elegant woman with an appealing sense of levity – and we sat in her beautiful garden surrounded by raspberries and lilies, while she told me about her visits to the East End with her late husband James Boswell who died in 1971. She pulled pictures off the wall and books off the shelf to show me his drawings, and then we went round to visit his daughter Sal who lives in the next street and she pulled more works out of her wardrobe for me to see. And when I left with two books of drawings by James Boswell under my arm as a gift, I realised it had been an unforgettable introduction to an artist who deserves to be better remembered.

From the vast range of work that James Boswell undertook, I have selected these lively drawings of the East End done over a thirty year period between the nineteen thirties and the fifties.There is a relaxed intimate quality to these – delighting in the human detail – which invites your empathy with the inhabitants of the street, who seem so completely at home it is as if the people and cityscape are merged into one. Yet, “He didn’t draw them on the spot,” Ruth revealed as I pored over the line drawings trying to identify the locations, “he worked on them when he got back to his studio. He had a photographic memory, although he always carried a little black notebook and he’d just make few scribbles in there for reference.”

“He was in the Communist Party, that’s what took him to the East End originally,” she continued, “And he liked the liveliness, the life and the look of the streets, and and it inspired him.” In fact, James Boswell joined the Communist Party in 1932 after graduating from the Royal College of Art and his lifelong involvement with socialism informed his art, from drawing anti-German cartoons in style of George Grosz during the nineteen thirties to designing the posters for the successful Labour Party campaign of 1964.

During World War II, James Boswell served as a radiographer yet he continued to make innumerable humane and compassionate drawings throughout postings to Scotland and Iraq – and his work was acquired by the War Artists’ Committee even though his Communism prevented him from becoming an official war artist. After the war, as an ex-Communist, Boswell became art editor of Lilliput influencing younger artists such as Ronald Searle and Paul Hogarth – and he was described by critic William Feaver in 1978 as “one of the finest English graphic artists of this century.”

Ruth met James in the nineteen-sixties and he introduced her to the East End. “We spent quite a bit of time going to Blooms in Whitechapel in the sixties. We went regularly to visit the Whitechapel when Robert Rauschenberg and the new Americans were being shown, and then we went for a walk afterwards,” she recalled fondly, “James had been going for years, and I was trying to make my way as a journalist and was looking at the housing, so we just wandered around together. It was a treat to go the East End for a day.”

James Boswell’s work is featured in East End Vernacular

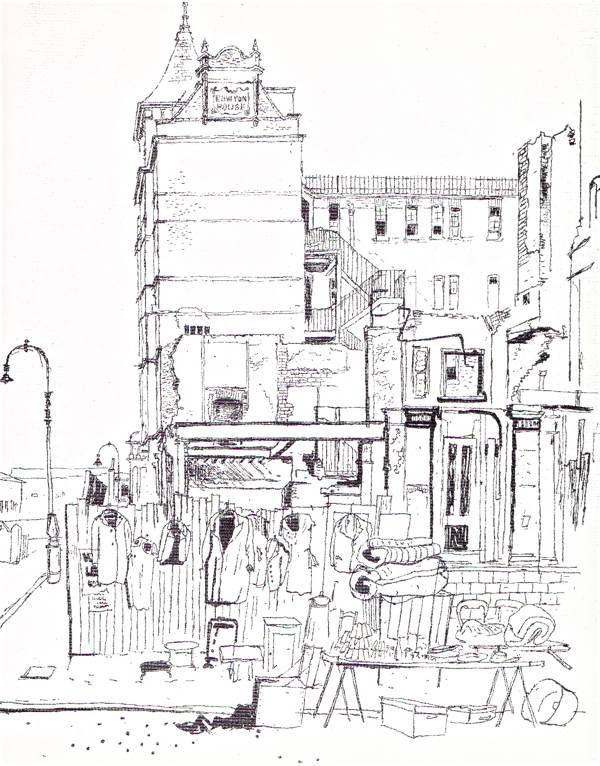

Rowton House

Old Montague St, Whitechapel

Gravel Lane, Wapping

Brushfield St, Spitalfields

Wentworth St, Spitalfields

Brick Lane

Fashion St, illustration by James Boswell from “A Kid for Two Farthings” by Wolf Mankowitz, 1953.

Russian Vapour Baths in Brick Lane from “A Kid for Two Farthings.”

James Boswell (1905-1971)

Leather Lane Market, 1937

Images copyright © Estate of James Boswell

You might also like to take a look at

In the footsteps of Geoffrey Fletcher

The Spitalfields Nobody Knows (Part One)

The Spitalfields Nobody Knows (Part Two)

Click here to order a copy of EAST END END VERNACULAR for £25

Jeffrey Johnson’s Favourite Spots

Enigmatic Photographer Jeffrey Johnson deposited a stack of his appealing pictures from the seventies and eighties with Archivist Stefan Dickers at the Bishopsgate Institute, including these photos of favourite spots in London. I cannot resist the feeling that Jeffrey is one after my own heart when I examine these characterful pictures of the capital’s forgotten corners.

Apostal’s

Buitifull Buttons

Arlington Way, N1

Broadway Market

Commercial Rd

Royal Exchange, City of London

Royal Exchange, City of London

King’s Cross

King’s Cross

King’s Cross

King’s Cross

King’s Cross

Teeth bought

Brick Lane

Barter St, Holborn

Great Ormond St, Bloomsbury

Little Montague Court, City of London

St Bartholomew’s Close, Smithfield

Albion Buildings

Alderney Rd

Photographs copyright © Jeffrey Johnson

You may also like to take a look at

The Forgotten Corners of Old London

Mystery Pictures of Brick Lane

Franta Belsky’s Sculpture in Bethnal Green

The Lesson by Franta Belsky (1959)

For years, I passed Franta Belsky’s bronze sculpture in Bethnal Green every Sunday on my way to and from the flower market in Columbia Rd without knowing the name of the artist. Born in 1921 in Brno, Czechoslovakia, Belsky fled to England after the German invasion and fought for the Czech Exile Army in France. Returning to Prague after the war, he discovered that most of his Jewish family had perished in the Nazi Holocaust, before fleeing again in 1948 when the Communists took over.

Creating both figurative and abstract work, Belsky believed that sculpture was for everyone. “You have to humanise the environment,” he said once, “A housing estate does not only need newspaper kiosks and bus-stop shelters but something that gives it spirit.”As you can see from this film of 1959, some local residents in Bethnal Green were equivocal about Belsky’s scupture at first – but more than half a century later it has become a much-loved landmark.

The Lesson by Franta Belsky (1921-2000)

You might also like to read about

Furniture Trade Cards Of Old London

I discovered these old furniture trade cards hidden in the secret drawer of a hypothetical cabinet

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to see my earlier selections

More Trade Cards of Old London

Yet More Trade Cards of Old London

Even More Trade Cards of Old London

Phil Maxwell’s Brick Lane

Tonight Tower Hamlets Development Committee decides upon the Truman Brewery’s application to build a shopping mall on Brick Lane with four floors of corporate offices on top. Click here for the link to watch the meeting live at 5:00pm

Phil Maxwell is the photographer of Brick Lane – no-one has taken more pictures here over the last thirty years than he. And now his astonishing body of work stands unparalleled in the canon of street photography, both in its range and in the quality of human observation that informs these eloquent images.

“More than anywhere else in London, Brick Lane has the organic quality of being constantly changing, even from week to week.” Phil told me when I asked him to explain the enduring fascination for a photographer. “Coming into Brick Lane is like coming into a theatre, where they change the scenery every time a different play comes in – a stage where each new set reflects the drama and tribulations of the wider world.”

Phil’s work is distinguished by a strong empathy, drawing the viewer closer. In particular, he is one of few photographers to have photographed the Bengali people in Spitalfields successfully, winning the trust of the community and portraying many of his subjects with relaxed intimacy. “That’s because I live on the other side of the tracks, and the vast majority of my neighbours are Bengalis – I’ve been to Bangladesh at least half a dozen times.” Phil revealed, “The main problem that Bengali families face is overcrowding, with parents and four or five kids living in one bedroom flats. That means their living space is not enough to be able to socialise and express themselves freely. And so, Brick Lane tends to be the place where they can feel free to be themselves and communicate with each other, in a way they can’t at home.”

When I confided to Phil that the lyrical quality of his portraits of old people appealed to me especially, he pointed out the woman with white hair, enfolding herself in her pale overcoat. “She seems bemused by what is happening round her, but in her appearance she is very much part of the built environment that surrounds her,” he said, thinking back over the years “I find older people have a kind of demeanour which derives from the environment they’ve been living in, and because of that they’re more interesting to photograph.”

In its mutable nature, Brick Lane presents an ideal subject for photography – offering an endless source of fleeting moments, that expose a changing society within a changing environment. And, since the early eighties, Phil Maxwell made it the focus of his life’s work to record this place, becoming the pre-eminent photographer of Brick Lane. “Whenever there’s a big fight on Brick Lane, the papers will send a photographer down to get some images, but that photographer has no relationship to the community.” Phil explained to me, conceding, “If my work has any authenticity, it is only because I lived here in the middle of the melting pot and I prefer it to anywhere else.”

“The bananas, the bridge and the man are all gone now.”

Photographs copyright © Phil Maxwell

More pictures by Phil Maxwell

The Cally In The Eighties

Last chance to book for tonight’s free webinar with Brick Lane traders discussing the threat of the Truman Brewery shopping mall on the day before Tower Hamlets Council decides on the planning application. Click here to register

Today Alan Dein enjoys a stroll along the Caledonian Rd forty years ago.

40 Caledonian Rd, 1983

The fascia of a clock repair shop has a clockface without hands, a seller of second-hand television sets advertises ‘The Bent TV Shop’, a stagnant canal basin slumbers in a post-industrial haze and a shady-looking sauna calls itself ‘KINGS X’ – yes, this is King’s Cross forty years ago.

Last November, when I heard of the passing of Leo Giordani whose Italian delicatessen ‘KC Continental Stores’ had been a much-loved King’s Cross institution for half a century, I was reminded of a fascinating collection of photographs that had been taken in the neighbourhood during the early eighties.

I came across these images while working on King’s Cross Voices, an oral history study that was conducted between 2004 to 2008. During these years, myself, my colleague Leslie McCartney and a group of volunteers collected some three hundred interviews accompanied by photographs and ephemera – all now held at the Camden Local Studies & Archives Centre.

The first decade of the new millennium proved to be a significant moment to interview people about their memories of living and working in a place that was in the early throes of massive redevelopment. Up to that point, King’s Cross had been locked in a twilight zone as a series of ill-thought-out development proposals had been thwarted by local residents and campaigners.

So the physical landscape of ‘the Cross’ just stagnated and, during the eighties and nineties, King’s Cross’ became synonymous with vice, sleaze and decay. It was depicted in the press as a bleak post-industrial wasteland, complete with seedy sex shops, dingy backstreets, and peppered with boarded-up Victorian houses. Yet many businesses like Leo’s KC Continental Stores kept going through this time when King’s Cross also offered low-rent creative spaces, social housing and squats, as well as headquarters for charities, trades unions and community projects.

The photographs had been languishing in the files of the planning team at Islington Council which administered the eastern section of King’s Cross. These images document the southernmost part of the mile-and-a-half long Caledonian Rd, affectionally dubbed by locals as ‘The Cally’. It links the eastern slopes of Camden Rd with Pentonville Rd in the south and was originally known as Chalk Rd. The name changed after the ‘Royal Caledonian Asylum’ was built in 1828, schooling children of exiled Scots who had been orphaned in the Napoleonic Wars. The asylum moved to Bushey in 1902 but the Caledonian name stuck. Today its former site is occupied by the Caledonian Housing Estate that neighbours Pentonville Prison.

While I was gathering memories of working and community life around the Cally – especially the King’s Cross end – I became fascinated by the geography, architecture and social history of the area. Contributors included landlords and publicans, shopkeepers and artists, street workers and community activists, and residents both former and current.

These photographs taken by Islington Council forty years ago document a world that was preserved in people’s memories but mostly disappeared by the time I was doing my interviews. It was vital these pictures should be archived as an evocative legacy, taken at what was a difficult time for this beloved King’s Cross neighbourhood.

The Bent TV Shop is now a Tesco

At Battlebridge Basin, the stagnant canal slumbers in a post-industrial haze

At the junction of Northdown St, a shady-looking sauna calls itself ‘KINGS X’

Albion Yard

North end of Balfe St

South end of Balfe St

Corner of Balfe St

Looking south down Caledonian Rd

76 & 78 Caledonian Rd

32 York Way

Keystone Crescent

KC Continental Stores

Bravington Block and the Lighthouse Building

King’s Cross Cinema, 1980 – it reopened as the Scala a year later

Images courtesy Islington Local History Centre & Camden Archives

You may also like to take a look at

Stephen Gill’s Trolley Women

When photographer Stephen Gill slipped a disc carrying heavy photographic equipment, he had no idea what the outcome would be. The physiotherapist advised him to buy a trolley for all his kit, and the world became different for Stephen – not only was his injured back able to recover but he found himself part of a select group of society, those who wheel trolleys around. And for someone with a creative imagination, like Stephen, this shift in perspective became the inspiration for a whole new vein of work, manifest in the fine East End Trolley Portraits you see here today.

Included now within the camaraderie of those who wheel trolleys – mostly women – Stephen learnt the significance of these humble devices as instruments of mobility, offering dominion of the pavement to their owners and permitting an independence which might otherwise be denied. More than this, Stephen found that the trolley as we know it was invented here in the East End, at Sholley Trolleys – a family business which started in the Roman Rd and is now based outside Clacton, they have been manufacturing trolleys for over thirty years.

In particular, the rich palette of Stephen Gill’s dignified portraits appeals to me, veritable symphonies of deep red and blue. Commonly, people choose their preferred colour of trolley and then co-ordinate or contrast their outfits to striking effect. All these individuals seem especially at home in their environment and, in many cases – such as the trolley lady outside Trinity Green in Whitechapel, pictured above – the colours of their clothing and their trolleys harmonise so beautifully with their surroundings, it is as if they are themselves extensions of the urban landscape.

Observe the hauteur of these noble women, how they grasp the handles of their trolleys with such a firm grip, indicating the strength of their connection to the world. Like eighteenth century aristocrats painted by Gainsborough, these women claim their right to existence and take possession of the place they inhabit with unquestionable authority. Monumental in stature, sentinels wheeling their trolleys through our streets, they are the spiritual guardians of the territory.

Photographs copyright © Stephen Gill