Where Dennis Severs Enjoyed A Pint

The immersive tour of Dennis Severs House I created for the Spitalfields Trust, as a re-imagination of the tours that Dennis Severs gave in the eighties, commences this Thursday 29th July and booking is open until the end of November.

One day, David Milne of Dennis Severs’ House in Folgate St took me along to the Hoop & Grapes in Aldgate for a pint, revisiting a special haunt that he was introduced to by Dennis Severs back in the nineteen eighties.

We walked together from Spitalfields up through Petticoat Lane until we arrived at the busy junction in Aldgate where traffic careers in every direction.“This was the major road in and out of London and it would always have been as full of people as it is now.” said David, as he peered down the road towards Whitechapel, wrinkling his brow to imagine centuries of travellers, before fixing his gaze directly across the road at three of the last remaining timber frame buildings surviving from before the fire of London. The central building, squeezed between its neighbours like a skinny waif sat between two fat people on a bus, was the Hoop & Grapes.

It is the oldest licensed house in the City, built in 1593 and originally called The Castle, then the Angel & Crown, then Christopher Hills, finally becoming the Hoop & Grapes – referring to the sale of both beer and wine – in the nineteen twenties. The first impression when you turn your back on the traffic to enter, is of the appealingly crooked Tudor frontage with sash windows fitted in the seventeen twenties at eccentric angles, and of two ancient oak posts guarding the entrance, each with primitive designs of vines incised upon them.

Stepping through the heavy door patched together over centuries, the plan of the narrow house is still apparent even though the partition walls have been removed. A narrow passageway ran ahead down the left of the building with small rooms leading off to the right, a structure which is revealed today by the placing of the beams in the ceiling and the bulges in the wall where the fireplaces in each room have been sealed up. Opening to your left is the bar, where the premises have expanded into the next house and to the back is flagged floor next to the largest chimney breast in a space that was a kitchen in the sixteenth century.

David and I enjoyed the privilege of access to the cellar where the landlady led us through a sequence of narrowing brick vaults built in the thirteenth century, until we reached the front of the building where she pointed out an old iron hook in the ceiling, held back by a lead catch. “No-one knows what this was for,” she admitted, prompting David to look down at his feet where a metal cover was set into the floor.“There was a well beneath,” he said, speculating,“the Aldgate pump was not far from here and the water table is high.” Then the landlady released the hook to hang vertical and it hung directly over the centre of the cover, perfect for hauling up a bucket. We all exchanged a smile of triumph at solving the puzzle, and stood together to appreciate this rare medieval space, essentially unchanged since Elizabeth I met Mary Tudor fifty yards away at Aldgate in 1553.

Upstairs, the landlady pointed out the site of a listening tube, centuries old yet covered over when a speaker system was fitted recently. This tube enabled whoever was in the cellar to hear what was spoken in the bar and vice versa. David believes it was used in the days of Oliver Cromwell by the landlord, who was in the pay of the authorities, to eavesdrop upon conspirators who chose this pub just outside the City gate for illicit liaisons, and there is no doubt that – thanks to the sparse renovations – once you have been here for a while you can begin to imagine the picture.

We sat down at the quiet corner table next to the crooked window with our drinks. “Dennis and I had this way of looking at things and making it more than it is,” confessed David to me with a contemplative affectionate smile “and that’s what we called ‘the theatre of life’. I used to come and visit him, and we’d go for walks around Spitalfields and end up here for a pint. We were looking for what remains – the signposts to the great City of old – the street that ran down to the City of London was full of houses like this. We would sit here and create a story about the merchants who lived in these ancient houses.”

In this no-man’s land between the City and Whitechapel, the Hoop & Grapes is a reliably peaceful place to go where just a few commuters drop in for a pint and tourists rarely appear – because it does not readily declare its history. Yet time gathers here in the stillness of this modest Tudor building – constructed atop a medieval foundation with eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth century accretions – while the world rushes past as it always has done.

Through his house in Folgate St, Dennis Severs’ reinvented the way that historic buildings are presented. When David Milne came here with Dennis Severs over forty years ago, all that was in the future, and today more than twenty years after his death, David is one of those who maintains Dennis Severs’ creation. “He was a remarkable man,” confided David, as we took our leave of the Hoop & Grapes, “and now this place is a signpost to my past with him.”

David Milne first came here with Dennis Severs over forty years ago

The thirteenth century cellars

An ancient hook above the well in the cellar

Two venerable oak posts carved with vines guard the door, and sash windows added in the seventeen twenties sit within a crooked sixteenth century structure

An insurance plate from 1782 still adorns the frontage

The three sixteenth century timber frame houses in Aldgate, predating the fire of London which came within fifty yards. The house on the right was refaced in brick in the eighteenth century

Archive photograph of the Hoop & Grapes courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Other Dennis Severs’ House stories

Where Dennis Severs Bought His China

The immersive tour of Dennis Severs House I created for the Spitalfields Trust, as a re-imagination of the tours that Dennis Severs gave in the eighties, commences this Thursday 29th July and booking is open until the end of November.

One day, David Milne of Dennis Severs’ House, got in touch to tell me about Stephen Long, an antique dealer who had dealt in early nineteenth century English china from a shop in the Fulham Rd since the nineteen sixties.

This was where Dennis Severs bought much of the china that graces the house in Folgate St, he revealed – adding that by Stephen Long had died and within the week the contents of his shop would be cleared out by an auction house. But before that happened, there might be an opportunity to visit and photograph one of London’s last traditional antique shops, he suggested.

Until then, I had not quite noticed how the old school antique shops have been vanishing from the world. In Kensington Church St and in the Portobello Rd, in streets formerly lined with antique dealers – where once I used to wander, window shopping at all the beautiful old things I would never buy – such businesses are thinning out and becoming sparser. Similarly in Fulham and Chelsea, part of the accepted landscape of London is quietly dissolving away.

David and I walked through Brompton Cemetery to reach the quiet stretch of the Fulham Rd where Stephen Long had his shop, beyond the fashionable street life of Chelsea yet not proxy to the bustle of Fulham Broadway either. “I had no idea he was ill,” David confessed, “I saw his shop was shut and a glass panel was broken. Nobody could contact him, so in mid-December they broke in and found him sick upstairs, where he lived. And he died in hospital in January.”

In a fine nineteenth century terrace, only one premises had its original shopfront intact, still in architectural unity with the upper storeys where the rest had been crudely modernised at street level to discordant effect. The name of Stephen Long caught my eye at once in its classic typeface, above the elegant five-bay Victorian display window. And, even before we entered, I recognised the shop as of the familiar kind I had visited a hundred times with my parents, for the delight of admiring the wonders yet ever wary that we might break something expensive. There were colourful old plates on wire stands and other pieces of china formally placed in symmetrical arrangements, their decorum offset by the whimsy of artificial fruit and flowers, and cheerful coloured paper lining the shelves.

“Stephen used to sit behind a low desk at the back of the shop – so that you couldn’t see him from the street, there in the shop in the darkness with beautiful stuff piled up around him,” recalled David, explaining how he discovered the connection with Dennis Severs, “I used to buy stuff from him and one day he told he knew a guy in Spitalfields.” Before Dennis Severs bought the house in Folgate St by which he is remembered, he lived in a mews in Gloucester Rd and gave rides around London in an open-top landau. Stephen Long told David, he remembered Dennis Severs parking the horse and carriage outside and coming in to buy things. Then, two years ago, Stephen Long visited Dennis Severs’ house at David’s invitation and when he saw the china, exclaimed, “I sold him all this!” At Dennis Severs’ House, the mass of china that decks the old dresser in the kitchen, the royal memorabilia in the parlour, the creamware and the teapots – it came from Stephen Long and his discreet price labels still remain on the underneath of the items to this day.

“What I loved about going into this shop, it was like stepping into the nineteenth century,” David confided to me as we entered the half light of the showroom, where most of the objects had been in stock for over twenty years but were now only resting in their former owner’s arrangements for one last afternoon. “In all the years I came to the shop, I never met anyone else in here,” David whispered, almost speaking to himself as he absorbed the atmosphere for the final time.

David told me Stephen Long was in his eighties, a quiet man, gentle, charming and of the old school, a dealer who knew his stuff. The shop was the manifestation of his sensibility and taste, after a lifetime of looking at things, displaying his eye for colour and form, and his playful delight in contrast and in gathering collections. “Like all the best dealers, he was a collector who only sold things to make room for the new,” said David and there it was, gleaming through the gloom – the last moment of one man’s treasure trove – just as he left it.

“He used to sit behind a low desk at the back of the shop – so that you couldn’t see him from the street.”

You may also like to read about

David Milne, Curator at Dennis Severs’ House

At Highgate Cemetery

If you seek to lose yourself in London and escape the scorching summer heat, Highgate Cemetery is the ideal destination. You step through the gothic-inspired gatehouse and take the winding path up the hill among the trees, with gracious architectural monuments, tombs and statues on either side. Foliage and shadow enclose the cemetery, shielding it from the city.

At the top of the hill you arrive at a grand entrance with exotically carved stone pillars and iron gates, hung with dense growth of ivy and creepers. You encounter deep shadows at the portal and, unavoidably, confront your own mortality. As you ascend the shady path alone towards the light, lined with doors, it is as if you are entering the ancient metropolis of a lost civilisation. But the residents have not fled, they are all still here under the permanent lockdown of death.

You wonder what you will find at the other end of this passageway. Yet you emerge again into the light to discover a narrow street of doorways leading to the left and the right, open to the sky and lined with flowers. As you pace around, you recognise that each one is subtly distinct from the others, with names to enable the holy postman. Within minutes, you discover this street is circular. You have arrived at the heart of the necropolis and you can walk for eternity around this street. You can change direction, but you can only travel in a circle.

Thank goodness there are stairs that permit you to escape and return to the world of the living, where you can stand and impassively observe this curious architectural feature at the heart of the cemetery. If you seek the soul of London, you will find it here in the rotunda at Highgate Cemetery.

Highgate Cemetery, Swain’s Lane, London N6 6PJ

You may also like to read about

The Queenhithe Mosaic

Queenhithe is a natural inlet of the Thames in the City of London, it means ‘Queen’s harbour’ and is named after Queen Matilda who granted a charter for the use of the dock at the beginning of the twelfth century. This is just one of two thousand years of historical events illustrated in a twenty metre mosaic installed upon the river wall at Queenhithe.

Commissioned by the City of London and paid for by 4C Hotel Group, it was designed by Tessa Hunkin and executed by South Bank Mosaics under the supervision of Jo Thorpe – and I recommend you take a stroll down through the City to the river, and study the intricate and lively detail of this epic work for yourself.

You may also like to read about

The Mystery Of Isabelle Barker’s Hat

Each day now, I am rehearsing actor Joel Saxon for the immersive tour of Dennis Severs House, commissioned by the Spitalfields Trust as a re-imagination of the tours that Dennis Severs gave in the eighties.

Tours commence next Thursday 29th July and booking is open until the end of November.

Even though I took this photograph of the hat in question, when I examined the image later it became ambiguous to my eyes. If I did not know it was a hat, I might mistake it for a black cabbage, a truffle, or an exotic dried fruit, or maybe even a specimen of a brain preserved in a medical museum.

Did you notice this hat when you visited the Smoking Room at Dennis Severs’ House in Folgate St? You will be forgiven if you did not, because there is so much detail everywhere and, by candlelight, the hat’s faded velvet tones merge unobtrusively into the surroundings. It seems entirely natural to find this hat in the same room as the painting of the gambling scene from William Hogarth’s “The Rake’s Progress” because it is almost identical to the hat Hogarth wore in his famous self-portrait, of the style commonly worn by men in his era, when they were not bewigged.

Yet, as with so much in this house of paradoxes, the hat is not what it appears to be upon first glance. If it even caught your eye at all because the gloom contrives to conjure virtual invisibility for this modest piece of headgear – if it even caught your eye, would you give it a second glance?

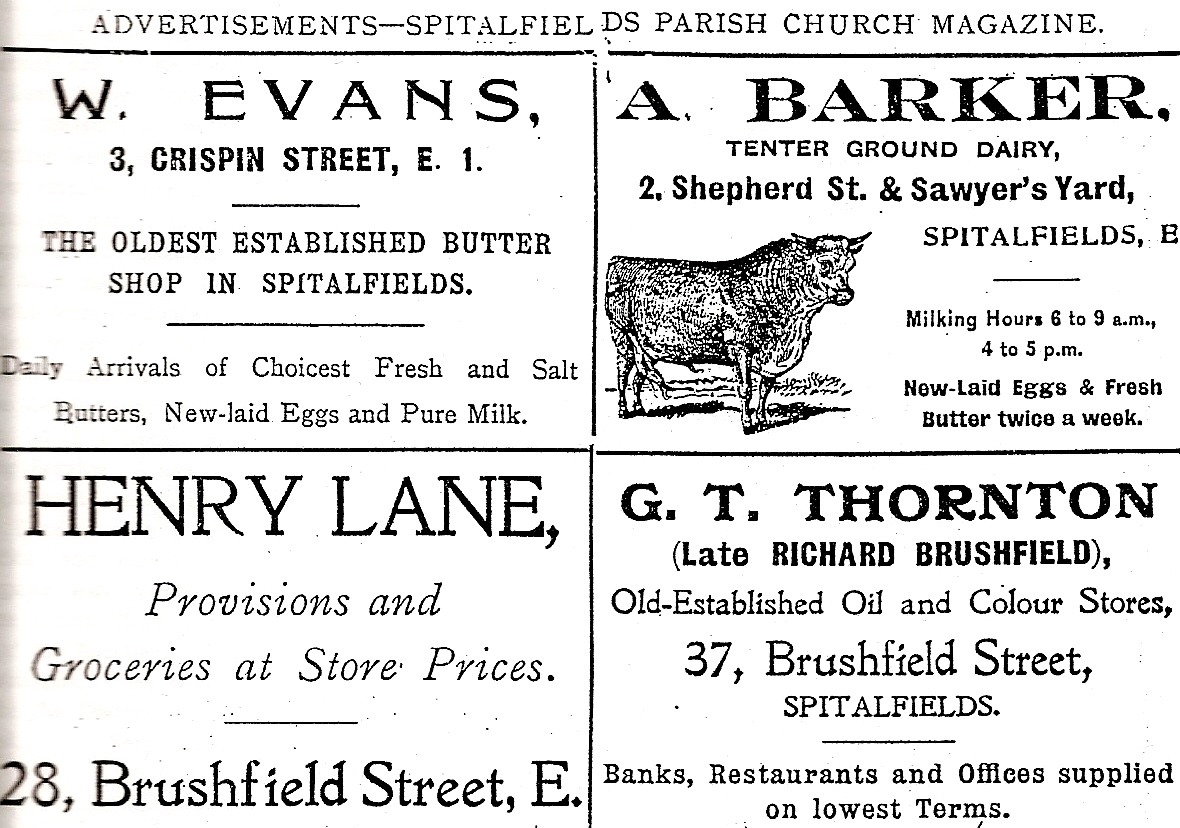

It was Fay Cattini who brought me to Dennis Severs’ house in the search for Isabelle Barker’s hat. Fay and her husband Jim befriended the redoubtable Miss Barker, as an elderly spinster, in the last years of her life until her death in 2008 at the age of ninety-eight. To this day, Fay keeps a copy of Isabelle’s grandparents’ marriage certificate dated 14th June 1853. Daniel Barker was a milkman who lived with his wife Ann in Fieldgate St, Whitechapel and the next generation of the family ran Barker’s Dairy in Shepherd St (now Toynbee St), Spitalfields. Isabelle grew up there as one of three sisters before she moved to her flat in Barnet House round the corner in Bell Lane where she lived out her years – her whole life encompassing a century within a quarter-mile at the heart of Spitalfields.

“I was born in Tenterground, known as the Dutch Tenter because there were so many Jews of Dutch origins living there. My family were Christians but we always got on so well with the Jews – wonderful people they were. We had a dairy. The cows came in by train from Essex to Liverpool St and we kept them while they were in milk. Then they went to the butchers. The children would buy a cake at Oswins the baker around the corner and then come and buy milk from us.” wrote Isabelle in the Friends of Christ Church magazine in 1996 when she was eighty-seven years old.

Fay Cattini first became aware of Isabelle when, in her teens, she joined the church choir which was enhanced by Isabelle’s sweet soprano voice. Isabelle played the piano for church meetings and tried to teach Fay to play too, using an old-fashioned technique that required balancing matchboxes on your hand to keep them in the right place. “I grew up with Isobel,” admitted Fay,“I think Isobel was one of the respectable poor whose life revolved around home and church. She had very thin ankles because she loved to walk, in her youth she joined the Campaigners (a church youth movement) and one of the things they did was to march up to the West End and back. She enjoyed walking, and she and her best friend Gladys Smith would get the bus and walk around Oxford St and down to the Embankment. Even when she was in her nineties, I never had to walk slowly with her.”

Years later, Fay and Jim Cattini shared the task of escorting Isabelle over to The Market Cafe in Fournier St for lunch six days a week. In those days, the cafe was the social focus of Spitalfields, as Fay told me,“Isabelle was quite deaf, so she liked to talk rather than listen. At The Market Cafe where she ate lunch every day, Isabelle met Dennis Severs. Dennis, Gilbert & George, and Rodney Archer were all very sweet to her. I don’t think she cooked or was very domestic but walking to The Market Cafe every day – good food and good company – then walking back again to her small flat on the second floor of Barnet House, that’s what kept her going.”

In fact, Fay remembered that Isobel gave her hat to Dennis Severs, who called her his “Queen Mother” in fond acknowledgement of her natural dignity, and he threw her an elaborate eightieth birthday party at his house in 1989. But although nothing ever gets thrown away at 18 Folgate St, when we asked curator David Milne about Isabelle Barker’s hat, he knew of no woman’s hat on the premises fitting the description – which was clear in Fay’s mind because Isabelle took great pride in her appearance and never went out without a hat, handbag and gloves.

“Although she was an East End person,” explained Fay affectionately,“she always looked very smart, quite refined, and she spoke correctly, definitely not a cockney. She had a pension from her job at the Post Office as a telephonist supervisor, but everything in her flat was shabby because she wouldn’t spend any money. As long as she had what she needed that was sufficient for her. She respected men more than women and refused to be served by a female cashier at the bank. Her philosophy of life was that you didn’t dwell on anything. When Dennis died of AIDS she wouldn’t talk about it and when her best friend Gladys had dementia she didn’t want to visit her. It was an old-fashioned way of dealing with things, but I think anyone that lives to ninety-eight is impressive. You had to soldier on, that was her attitude, she was a Victorian.”

When Fay showed me the photo you see below, of Isabelle Barker with Dennis Severs at her eightieth birthday party, David realised at once which hat belonged to her. Even though it looks spectacularly undistinguished in this picture, David spotted the hat in the background of the photo on the stand in the corner of the Smoking Room – which explains why the photo was taken in this room which was otherwise an exclusive male enclave.

At once, David removed the hat from the stand in the Smoking Room where it sat all these years and confirmed that, although it is the perfect doppel-ganger of an eighteenth-century man’s hat, inside it has a tell-tale label from a mid-twentieth century producer of ladies’ hats. It was Isabelle Barker’s hat! The masquerade of Isabelle Barker’s hat fooled everyone for more than twenty years and, while we were triumphant to have discovered Isabelle’s hat and uncovered the visual pun that it manifests so successfully, we were also delighted to have stumbled upon an unlikely yet enduring memorial to a remarkable woman of Spitalfields.

Dennis Severs & Isabelle Barker at her eightieth birthday party with the hat in the background

William Hogarth wearing his famous hat

Barker’s Dairy as advertised in the Spitalfields Parish Magazine in 1923

Fay and Isabelle in 2001

Dennis Severs House, 18 Folgate St, Spitalfields, E1 6BX

You may also like to read about

Ebbe Sadolin’s London

Danish Illustrator Ebbe Sadolin (1900-82) visited London in the years following the War to capture the character of the capital, just recovering from the Blitz, in a series of lyrical drawings executed in elegant spidery lines. Remarkably, he included as many images of the East End as the West End and I publish a selection of favourites here from the forties.

George & Dragon, Shoreditch

St Katherine’s Way, Wapping

The Prospect of Whitby, Wapping

Stocks, Shoreditch

Petticoat Lane

Tower Green, Tower of London

The Olde Cheshire Cheese, Fleet St

Rough Sleeper, Shoreditch

Islington Green

Nightingale Lane, Wapping

Fleet St

Wapping churchyard

Tower of London

St Pancras Station

High St, Plaistow

Bride of Denmark, Queen Anne’s Gate

Liverpool St Station

You may also like to look at

Huguenot Fan Makers

Fan commemorating the Battle of Dettingen by Francis Chassereau, 1743. Lacquered wood, etching & watercolour on paper (Helene Alexander Collection)

Whilst the Fan Museum is closed, curator Jacob Moss reveals recent research into Huguenot fan makers in an online talk organised by Huguenots of Spitalfields, tomorrow Thursday July 22nd at noon.

From the seventeenth century, the making and selling of handheld fans in London involved significant numbers of Huguenot refugees. Jacob Moss explores the complexities of a once thriving industry by tracing the Chassereau dynasty who, following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, fled from France to London where successive generations were fan-makers throughout the eighteenth century.

The Fan Museum is the brainchild of Helene Alexander who has devoted her life with an heroic passion to assembling the world’s greatest collection of fans – which currently stands at over five thousand, dating from the eleventh century to the present day. Below you can see a selection from the museum collection.

Folding fan with bone monture & woodblock printed leaf commemorating the Restoration of Charles II. English, c. 1660 (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan (opens two ways) with ivory monture. Each stick is affixed to a painted palmette. European (probably French), c. 1670s (Helene Alexander Collection)

Ivory brisé fan painted with curious depictions of European figures. Chinese for export, c. 1700(Helene Alexander Collection)

Ivory brisé fan painted in the style of Hondecoeter. Dutch, c. 1700 (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan with bone monture. The printed & hand-coloured leaf has a mask motif with peepholes. English, c. 1730

Folding fan with ivory monture, the guards with silver piqué work. The leaf is painted on the obverse with vignettes themed around the life cycle of one man. European (possibly German) c. 1730/40 (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan with ivory monture & painted leaf. English, c. 1740s (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan with ivory monture & painted leaf, showing Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens. English, c. 1750s

Folding fan with wooden monture & printed leaf, showing couples promenading. French, c. 1795-1800 (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan with gilt mother of pearl monture & painted leaf, signed ‘E. Parmentier. ’ French, c. 1860s

‘Landscape in Martinique’, design for a fan by Paul Gauguin. Watercolour & pastel on paper. French, c. 1887

Folding fan with blonde tortoiseshell monture, one guard set with guioché enamelling, silver & gold work by Fabergé. Fine Brussels lace leaf. French/Russian, c. 1880s (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan with smoked mother of pearl monture, the leaf painted by Walter Sickert with a music hall scene showing Little Dot Hetherington at the Old Bedford Theatre. English, c. 1890

Folding fan with tortoiseshell monture carved to resemble sunrays. Canepin leaf studded with rose diamonds & rock crystal, & painted with a female figure & putti amidst clouds, signed ‘G. Lasellaz ’92’. French, c. 1892 (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan with horn monture & painted leaf, signed ‘Luc. F.’ French, c. 1900

Folding fan with ivory & mother of pearl monture, the painted leaf, signed (Maurice) ‘Leloir.’ French, c. 1900 (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan with mother of pearl monture & painted leaf, signed ‘Billotey.’ French, c. 1905 (Helene Alexander Collection)

Horn brisé fan with design of brambles & insets of mother of pearl. French, c.1905 (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan with Art Nouveau style tinted mother of pearl monture & painted leaf, signed ‘G. Darcey.’ French, c. 1905 (Helene Alexander Collection)

Folding fan with tortoiseshell monture & feather ‘marquetry’ leaf. French, c. 1920

The Fan Museum, 12 Crooms Hill, Greenwich, SE10 8ER