At The Lutheran Church

The Altar and Pulpit at St George’s German Lutheran Church, Alie St

In Aldgate, caught between the thunder of the traffic down Leman St and the roar of the construction on Goodman’s Fields sits a modest church with an unremarkable exterior. Yet this quiet building contains an important story, the forgotten history of the German people in the East End.

Dating from 1762, St George’s German Lutheran Church is Britain’s oldest surviving German church and once you step through the door, you find yourself in a peaceful space with a distinctive aesthetic and character that is unlike any other in London.

The austere lines of the interior emphasise the elegant, rather squat proportion of the architecture and the strong geometry of the box pews and galleries is ameliorated by unexpected curves and fine details. In fact, architect Joel Johnson was a carpenter by trade which may account for the domestic scale and the visual dominance of the intricately conceived internal wooden structure. Later iron windows of 1812, with their original glass in primary tones of red and blue, bring a surprising sense of modernity to the church and, even on a December afternoon, succeed in dispelling the gathering gloom.

This was once the heart of London’s sugar-baking industry and, from the mid-seventeenth century onwards, Germans brought their particular expertise to this volatile and dangerous trade, which required heating vast pans of sugar with an alarming tendency to combust or even explode. Such was the heat and sticky atmosphere that sugar-bakers worked naked, thus avoiding getting their clothes stuck to their bodies and, no doubt, experiencing the epilatory qualities of sugar.

Reflecting tensions in common with other immigrant communities through the centuries, there was discord over the issue of whether English or the language of the homeland should be spoken in church and, by implication, whether integration or separatism was preferable – this controversy led to a riot in the church on December 3rd 1767.

As the German community grew, the church became full to overcrowding – with the congregation swollen by six hundred German emigrants abandoned on their way to South Carolina in 1764. Many parishioners were forced to stand at the back and thieves capitalised upon the chaotic conditions in which, in 1789, the audience was described in the church records as eating “apples, oranges and nuts as in a theatre,” while the building itself became, “a place of Assignation for Persons of all descriptions, a receptacle for Pickpockets, and obtained the name St George’s Playhouse.”

Today the church feels like an empty theatre, maintained in good order as if the audience had just left. Even as late as 1855, the Vestry record reported that “the Elders and Wardens of the Church consist almost exclusively of the Boilers, Engineers and superior workers in the Sugar Refineries,” yet by the eighteen-eighties the number of refineries in the vicinity had dwindled from thirty to three and the surrounding streets had descended into poverty. Even up to 1914, at one hundred and thirty souls, St Georges had the largest German congregation in Britain. But the outbreak of the First World War led to the internment of the male parishioners and the expulsion of the females – many of whom spoke only English and thought of themselves as British.

In the thirties, the bell tower was demolished upon the instructions of the District Surveyor, thus robbing the facade of its most distinctive feature. Pastor Julius Reiger, an associate of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a leading opponent of the Nazis, turned the church into a relief centre offering shelter for German and Jewish refugees during World War II, and the congregation continued until 1996 when there only twenty left.

St George’s is now under the care of the Historic Chapels Trust and opens regularly for concerts and lectures, standing in perpetuity as a remembrance of more than two centuries of the East End’s lost German community.

The classically-patterned linoleum is a rare survival from 1855

The arms of George III, King of England & Elector of Hanover

The principal founder of the church, Diederick Beckman

The Infant School was built in 1859 as gift from the son of Goethe’s publisher, W. H. Göschen

Names of benefactors carved into bricks above the vestry entrance.

St Georges German Lutheran Church, c. 1920

The bell turret with weathervane before demolition in 1934

The original eighteenth century weathervane of St George & the Dragon that was retrieved from ebay

St George’s German Lutheran Church, 55 Alie Street, E1 8EB

A Tourist In Whitechapel

Let us search the recesses of our memories to recall those distant days when London was frequented by tourists from overseas. I discovered this comic pamphlet of 1859 in the Bishopsgate Institute which gives a fictional account of the experiences of a French tourist in Whitechapel yet permits us a rare glimpse of East End street life in that era too.

Monsieur Theophile Jean Baptiste Schmidt was a great observer of human nature. He was a great traveller too, for he had been across the Atlantic. But he had never been to London, so to London he determined to come.

When he arrived at London Bridge, to which he came in his Boulogne steamboat, he was met by his friend and countryman, Monsieur Hippolyte Lilly, who had resided some years in the city and knew all about its ways. Now Monsieur Lilly was a bit of a wag, so he determined to play Monsieur Schmidt a practical joke. Instead of taking his friend to the West End of London, when he landed, he led him to Whitechapel, and lodged him in a small public house called the Pig & Whistle.

“Baptiste, my friend,” said Hippolyte, “The English are a very strange people and you must not offend them – if they ask you for anything, you must give it at once.”

The Lost Child

No sooner therefore were the friends in Whitechapel, than they sallied out to see London. The stranger was very much astonished at the throng of people and vehicles, and they had not gone far before they saw a little crowd assembled on the pathway, so they at once stopped to see what was going on. Looking over the shoulders of a couple of young ladies they discovered a little child being questioned by a policeman.

“What is the matter?” asked Hippolyte. “Child lost,” replied the policeman. “Better give the man a shilling,” said Hippolyte to his friend. Baptiste therefore put his hand in his pocket and drew out a long silk purse, and taking from it a franc presented it to the policeman, who received it with a nod and a knowing wink.

The Benefits of a Long Purse

The action of the foreigner was not lost upon the crowd, and in a few minutes the friends found themselves surrounded by eager applicants. A little boy with a broom tumbled head over heels for their diversion, a Jew offered them a knife with twenty blades. an Indian begged them to buy a tract, a cabman wished to have the honour of drinking their healths, a boy offered them apples at three a penny, a woman with a child in her arms asked them to treat her to glass of gin, a man with a board requested them to fit themselves with a suit of clothes and a little girl wished to sell them a string of onions. To all of these people Monsieur Baptiste gave some piece of money, so that he was soon a very popular character. The policeman, however, cleared the way and they walked on.

The Conductors of the London Press

Presently they came to the outside of a newspaper dealers, where they saw a crowd of boys and men, laughing, talking, and playing. “These are the conductors of the London Press,” said Hippolyte.

The Disputed Fare

Soon afterwards they witnessed, and took part in, a dispute between a gentleman with a great moustache, a policeman, and a cab driver assisted by a variety of little boys. Baptiste soon settled the dispute by giving the cabman a shilling.

The Great Market

“I will now take you to the Great Market,” said Hippolyte, leading him through the dense crowd assembled round the butchers’ shambles in Whitechapel.

Monsieur Baptiste wondered very much at all he saw, thought the flaming gaslight, streaming over the heads of the people, “a very fine sight,” allowed himself to be pushed and hustled to and fro in the throng with perfect good humour, and was not in the least offended when one stall keeper offered him five bundles of firewood for a penny, or when another recommended him to invest sixpence in the purchase of a dog collar, or when a third – stroking his upper lip – politely asked him whether she should show him the way to the half-penny shaving shop.

Nor did he doubt for a moment what his friend told him was true when he was informed that this was the principal market for the supply of London with fresh meat. At last however, he expressed a desire to get out of the hot, unwholesome throng of poor people, which became every moment more dense, more noisy, and more bewildering.

The English Aristocracy

“Let us have one little glass of wine,” said Hippolyte, and forthwith they found themselves in the centre of a throng in a low gin shop.

The space in front of the counter was crowded with people of the poorest sort – an Irish labourer, in a smock frock and trousers tied below the knee with a hay band, was treating a miserable-looking woman to a glass of gin – a poor, half-starved girl was trying to persuade her tipsy father to go home, while another child was staggering under the weight of a baby on one arm and a gin bottle under the other – a miserable hag of a woman was crying ballads in a cracked voice – while a dirty-faced man was selling shrimps and pickled eels from a basket on his arm – and a Whitechapel dandy was joking with the smart barmaid – whose master stood at the door of his private parlour and smoked his cigar with the air of a lord.

A very hot, disagreeable odour filled the place, so that Monsieur Baptiste was obliged he must go home to his hotel. But just before he reached the door of the gin shop, he turned to his friend and asked, “What sort of people are these?”

“These are the aristocracy of England,” said Hippolyte. “These?” exclaimed Baptiste, beginning to see his friend’s joke, “then take me to see the poor.”

How many other places the friends visited that evening, how many jokes Hippolyte played upon Baptiste, and how many other shillings the foreigner spent on his first day in London, I cannot tell you. But I know that he laughed a good deal at the idea of seeing the wrong end of London first.

“Nevertheless, ” Baptiste exclaimed the next morning, “London is a very fine, great, big wonderful city.”

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

Victoria Park Model Steam Boat Club

Spitalfields Life contributing photographer, Lucinda Douglas-Menzies became fascinated by the Victoria Park Model Steam Boat Club while out walking in the park. Over successive Sundays, her interest grew as she went back to watch the regattas, meet the members and learn the story of the oldest model boat club in the world, founded in 1904. Her photographic essay records the life of this society of gentle enthusiasts, many of whom have been making and racing boats on this lake for generations, updating the designs and means of propulsion for their intricate craft in accordance with the evolution of maritime vessels over more than a century. Starting on Easter Sunday, the club holds as many as seventeen regattas annually.

“Meet you at ten o’clock Sunday morning at the boating lake!” was the eager response of Norman Lara, the chairman, when Lucinda rang to enquire about his club. “On the morning I arrived, a group of about a dozen model boat enthusiasts were already settled in chairs by the water’s edge with a variety of handmade boats on display.” explained Lucinda, who was treated to a tour of the clubhouse by Norman. “We are very lucky, one of the few clubs to have this. Tower Hamlets are very good to us, they keep the weeds down in the lake and last year we were given a loo.” he said, adding dryly, “It only took a hundred years to get one.”

Meanwhile, the members had pulled on their waders and were preparing their vessels at the water’s edge, before launching them onto the sparkling lake. Here Norman introduced Lucinda to Keith Reynolds, the club secretary, who outlined the specific classes of model boat racing with the precision of an authority, “There are five categories of “straight running” boats. These include functional, scale boats (fishing boats, cabin cruisers, etc), scale ships (warships, cruise boats, liners,merchant ships, liners, merchant ships – boats on which you could sustain life for more than seven days), metre boats (with strict rules of engine size and length) and – we had to create a special category for this one – called “the wedge,” basically a boat made of three pieces of wood with no keel, ideal for children to start on.” In confirmation of this, as Lucinda looked around, she saw children accompanied by their parents and grandparents, each generation with their boats of varying sophistication and period design, according to their owners’ experience and age.

Readers of Model Engineering Magazine were informed in 1907 that “the Victoria Park Model Steam Boat Club were performing on a Saturday afternoon before an enormous public of small boys who asked, ‘What’s it go by mister?'” It is a question that passersby still ask today, now that additional racing classes have been introduced for radio controlled boats with petrol engines and even hydroplanes.

“We have around sixty members,” continued Keith enthusiastically, “but we could with some more, as a lot don’t sail their boats any longer, they just enjoy turning up for a chat. It’s quiet today, but you should come back next Sunday to our steam rally when the bank will be thick with owners who bring their boats from all over. Some are so big they run on lawn mower engines!”

It was an invitation that Lucinda could not resist and she was rewarded with a spectacle revealing more of the finer points of model boat racing. She discovered that “straight running,” which Keith had referred to, is when one person launches a boat with a fixed rudder along a course (usually sixty yards long) where another waits at the scoring gates to catch the vessel. The closer to a straight course your boat can follow, the more points you win, defined by a series of gates around a central white gate, which scores a bull’s-eye of ten points if you can sail your boat through it. On either side of the white gate are red, yellow and orange gates each with a diminishing score, because the point of the competition is to discover whose boat can follow the truest course.

Witnessing this contest, Lucinda realised that – just like still water concealing deep currents – as well as having extraordinary patience to construct these beautiful working models, the members of the boat club also possess fiercely competitive natures. This is the paradox of sailing model boats, which appears such a lyrical pastime undertaken in the peace and quiet of the boating lake, yet when so much investment of work and ingenuity is at stake (not to mention hierarchies of individual experience and different generations in competition), it can easily transform into a drama that is as intense as any sport has to offer.

Lucinda’s eloquent pictures capture this subtle theatre adroitly, of a social group with a shared purpose and similar concerns, both mutually supportive and mutually competitive, who all share a love of the magic of launching their boats upon the lake on Sundays in Summer. It is an activity that conjures a relaxed atmosphere – as, for over a century, walkers have paused at the lakeside to chat in the sunshine, watching as boats are put through their paces on the water and scrutinising the detail of vessels laid upon the shore, before continuing on their way.

Photographs copyright © Lucinda Douglas-Menzies

At Embassy Electrical Supplies

Mehmet Murat

It comes as no surprise to learn that at Embassy Electrical Supplies in Clerkenwell, you can buy lightbulbs, fuses and cables, but rather more unexpected to discover that, while you are picking up your electrical hardware, you can also purchase olive oil, strings of chili peppers and pomegranate molasses courtesy of the Murat family groves in Cyprus and Turkey.

At certain fashionable restaurants nearby, “Electrical Shop Olives” are a popular feature on the menu, sending customers scurrying along to the Murats’ premises next morning to purchase their own personal supply of these fabled delicacies that have won acclaim in the global media and acquired a legendary allure among culinary enthusiasts.

How did such a thing come about, that a Clerkenwell electrical shop should be celebrated for olive oil? Mehmet Murat is the qualified electrician and gastronomic mastermind behind this singular endeavour. I found him sitting behind his desk at the rear of the shop, serving customers from his desk and fulfilling their demands whether electrical or culinary, or both, with equal largesse.

“I am an electrician by trade,” he assured me, just in case the fragrance of wild sage or seductive mixed aromas of his Mediterranean produce stacked upon the shelves might encourage me to think otherwise.

“I arrived in this country from Cyprus in 1955. My father came a few years earlier, and he got a job and a flat before he sent for us. In Cyprus, he was a barber and, according to our custom, that meant he was also a dentist. But he got a job as an agent travelling around Cyprus buying donkeys for Dr Kucuk, the leader of the Turkish Cypriots at that time – the donkeys were exported and sold to the British Army in Egypt. What he did with the money he earned was to buy plots of land around the village of Louroujina, where I was born, and plant olive saplings. He and my mother took care of them for the first year and after that they took care of themselves. Once they came to the UK, they asked relatives to watch over the groves. They used to send us a couple of containers of olive oil for our own use each year and sold the rest to the co-operative who sold it to Italians who repackaged it and sold it as Italian oil.

I trained as an electrician when I left school and I started off working for C.J. Bartley & Co in Old St. I left there and became self-employed, wiring Wimpy Bars, Golden Egg Restaurants and Mecca Bingo Halls. I was on call twenty-four hours and did electrical work for Faye Dunaway, the King of Jordan’s sister and Bill Oddie, among others. Then I bought this shop in 1979 and opened up in 1982 selling electrical supplies.

In 2002, when my father died, I decided I was going to bring all the olive oil over from Louroujina and bottle it all myself, which I still do. But when we started getting write-ups and it was chosen as the best olive oil by New York Magazine, I realised we had good olive oil. We produce it as we would for our own table. There is no other secret, except I bottle it myself – bottling plants will reheat and dilute it.

If you were to come to the village where I was born. you could ask any shopkeeper to put aside oil for your family use from his crop. I don’t see any difference, selling it here in my electrical shop in Clerkenwell. It makes sense because if I were to open up a shop selling just oil, I’d be losing money. The electrical business is still my bread and butter income, but many of the workshops that were my customers have moved out and the Congestion Charge took away more than half my business.

Now I have bought a forty-five acre farm in Turkey. It produces a thousand tons of lemons in a good year, plus pomegranate molasses, sweet paprika, candied walnuts and chili flakes. We go out and forage wild sage, wild oregano, wild St John’s wort and wild caper shoots. My wife is there at the moment with her brother who looks after the farm, and her other brother looks after the groves in Cyprus.”

Then Mehmet poured a little of his precious pale golden olive oil from a green glass bottle into a beaker and handed it to me, with instructions. The name of his farm, Murat Du Carta, was on the label beneath a picture of his mother and father. He explained I was to sip the oil, and then hold it in my mouth as it warmed to experience the full flavour, before swallowing it. The deliciously pure oil was light and flowery, yet left no aftertaste on the palate. I picked up a handful of the wild sage to inhale the evocative scent of a Mediterranean meadow, and Mehmet made me up a bag containing two bottles of olive oil, truffle-infused oil, marinated olives, cured olives, chili flakes and frankincense to carry home to Spitalfields.

We left the darkness of the tiny shop, with its electrical supplies neatly arranged upon the left and its food supplies tidily stacked upon the right. A passing cyclist came in to borrow a wrench and the atmosphere was that of a friendly village store. Outside on the pavement, in the sunshine, we joined Mark Page who forages truffles for Mehmet, and Mehmet’s son Murat (known as Mo). “I do the markets and I run the shop, and I like to eat,” he confessed to me with a wink.

Carter, the electrical shop cat

From left to right, Mark Page (who forages truffles), Murat Murat (known as Mo) and Mehmet Murat.

Embassy Electrical Supplies, 76 Compton St, Clerkenwell, EC1V 0BN

At London Trimmings

Moosa, Ashraf & Ebrahim Loonat

If you ever wondered where the Pearly Kings & Queens get the pearl buttons for their magnificent outfits, I can disclose that London Trimmings – the celebrated family business run by the three Loonat brothers in the Cambridge Heath Rd – is the place they favour. And with good reason, as I discovered when I went round to investigate yesterday, because this shop has a mind-boggling selection of wonderful stuff at competitive prices.

Zips and buttons and buckles and threads and tapes and ribbons and snap fasteners and elastic and eyelets and cords and braids and marking chalk and pins, and a whole lot of other coloured and sparkly things, comprise the biggest magpie’s nest on the planet. Now I shall no longer go to fancy West End stores to buy taffeta ribbon to tie up my gifts and pay several pounds for just a couple of metres – not since I discovered that here in Whitechapel you can get a whole reel for five quid and choose from every colour of the rainbow too.

With his lively dark brown eyes and personable nature, Moosa Loonat was my expert guide to this haberdashery labyrinth. He took me on a tour starting in the trade orders department which occupies one of London Trimmings’ two premises in this fine red brick nineteenth century terrace of shops, built by the brewery that once stood across the road. Translucent glass windows might discourage the casual customer, but in fact everyone is welcome in this extraordinary store which feels more like a warehouse than a shop.

Once we had trawled through the crowded aisles here and in the basement, with Moosa pulling out all imaginable kinds of zips and buckles and toggles to explain the stories behind each and every one, he assured me with a proprietorial grin, “I know where everything is, because if you pay for it you know.” I surmise that Moosa said this because while everything has its place at London Trimmings, the overall effect might be described as organised chaos of the most charismatic kind.

Yet, as we explored, Moosa told me the story of the business and I learned there was even more going on here than you can see on the crowded shelves of this extraordinary emporium.

“The shop was started by my father Yousuf Loonat and his partner Aziz Matcheswala in 1971 at the corner of Whitechapel High St and New Rd. My dad came to this country from Gujurat just after the war. He went to Bradford where all the mills were and he worked his way down to Leicester, and from Leicester to London. He told me, at first, he worked in a factory manufacturing street lights and, in Leicester, he went into the food trade and then he got into the textile trade.

At eight years old, I used to go and help count out buttons for my father. Every single holiday, he’d say, “I’ve got lots of work for you.” In 1987, when I was seventeen years old, my father and his partner split, so he gave me a choice – “Either go to university or join the family business – but if you don’t, I’ll sell it.” I took the opportunity and I’m happy that I did. That choice was offered to my brothers too and we realised that if we didn’t all club together, we would lose it. Now every brother runs a different department.

In 1985, we had a fire and lost everything – a couple of hundred thousand pounds of stock and we only had thirty thousand pounds insurance. It was an arson attack. I remember it clearly, it was a dramatic time for the family and my dad was really upset. All our suppliers helped us, they put a freeze on what we owed them until we could repay it and allowed us a new credit account. They contributed to fitting out this new shop in the Cambridge Heath Rd too, they even paid for the sign.

It was busy in the old days, everything was sold by the box then, we had four or five vans in the road and we wouldn’t even entertain student customers. Fifteen years ago, every shop in Brick Lane had a factory above it. In this immediate neighbourhood, we had a thousand customers, now we have a hundred here. We supply the leather trade, the bag trade, the garment trade, the jacket trade, the dry-cleaning and alteration trade, and the shoe repair trade. We cater to students who buy one button and to designers like Mulberry, Hussein Chayalan, Vivienne Westwood and Alexander McQueen, and to High St stores like Top Man and River Island. During London Fashion Week, we had forty people in the shop all wanting to be served first.

Our main speciality is zips, you can buy one for 5p up to £20. We have two hundred different styles and each comes in several sizes. Other suppliers only stock up to No 5, but we have No 6, No 7, No 8, No 9, and No 10 -we even have No 4. We have double-ended zips, fluorescent zips, invisible zips, plastic zips, pocket zips, copper zips, aluminium zips, steel zips, nickel zips, satin zips and waterproof zips.

One customer comes from Ireland, an eighty-five year old man, he comes over every month with a suitcase, packs it up and is gone. Another customer comes regularly from Iceland, she spends two days in here to see what’s new. We had one tailor, he sent back an empty box of 1,044 pins he bought twenty-five years previously, saying “I’d like another one but this is the last I will need because I am over seventy.” Sometimes, people ring from New Zealand to buy press fasteners for the covers on on open-top vintage cars. Kanye West came in twice before we recognised who he was, he came in four or five times altogether, choosing trimmings. He spent a couple of hours each time and had a cup of tea.

I arrive at eight-thirty and I work until seven each day. I do an eleven hour shift. I could choose not to come because I’ve got the staff, but I’m a workaholic. We don’t open at weekends but I still come in on Saturdays to catch up. One day I could be serving customers at the counter, the next day unloading a container and the next out on the road to visit customers. It’s never the same. It’s not a mundane, everything the same, day-in-day-out job. We’ve had my father, me and my nephews all in here at once – three generations working in the same place. Some of the staff have been here thirty years and all the youngsters who came to work here straight from school have stayed.

We run a tight ship financially. The last to get paid will be me and my brothers. We only get our wages if the money’s there but if it’s not, we don’t take it.”

Moosa Loonat – “The last to get paid will be me and my brothers. We only get our wages if the money’s there but if it’s not, we don’t take it.”

Teresa Brace, Manager of Haberdashery – “It’s a lot tidier on my side of the shop!”

Moosa – “As you can see, we’re short of space…”

Ebrahim Loonat

Shirley Mayhew, Accounts Department – in the trimmings business since 1980.

“the biggest magpie’s nest on the planet”

London Trimmings, 26-28 Cambridge Heath Rd, London E1 5QH.

John Minton’s East End

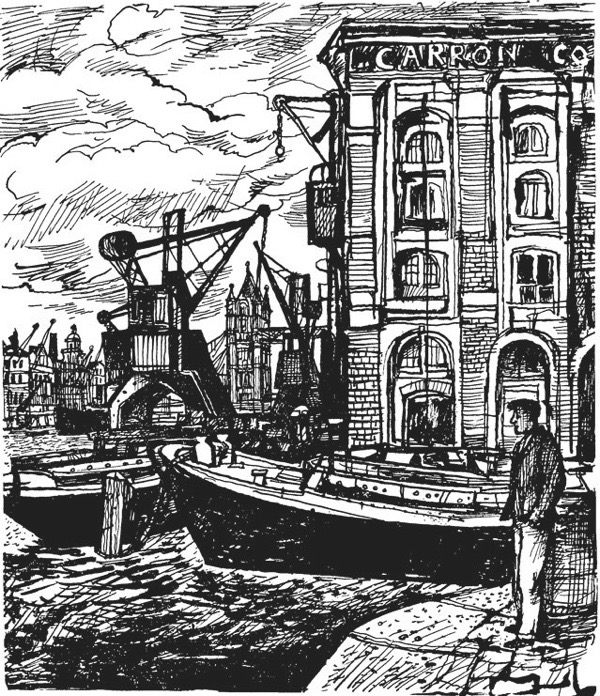

Martin Salisbury author of The Snail that climbed the Eiffel Tower, a monograph of John Minton’s graphic work, explores Minton’s fascination with the East End.

Never quite accepted by the establishment during his brief, rather tragic life, artist John Minton (1917—1957) has divided opinion ever since. Brilliant illustrator, inspirational teacher, prodigious habitué of Soho and Fitzrovia drinking establishments, Minton was bound to enter the folklore of post-war London. Somehow, he embodied the mood of elegiac romanticism that pervaded the arts through the forties and into the early fifties before fizzling out to be replaced by a more forward-looking, assertive art in the form of American abstract expressionism and British ‘kitchen-sink’ realism.

His life, riddled as it was with contradictions, began on Christmas Day 1917 in a wooden house near Cambridge, of an architectural style that some have termed ‘Gingerbread,’ and ended just under forty years later in Chelsea. He had apparently taken his own life. More than a hundred years after his birth, Minton is finally receiving the recognition enjoyed by other mid-century greats, Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious and John Piper.

Arguably, John Minton was at his best as a graphic and commercial artist, perhaps best known for his sublime illustrations for publisher John Lehmann to Elizabeth David’s highly influential food writing and Alan Ross; Corsica travel journal, Time Was Away, a lavish anti-austerity production. Yet Minton’s urban romanticism found its way into many commercial commissions too. Wartime drawings of bombed-out buildings in Poplar still exhibited the samr overwrought theatricality that was a feature of his work while under the spell of friend and fellow artist, Michael Ayrton.

In the immediate post-war years, as Minton’s work drew more consistently on direct observation, his visual vocabulary matured and his frequent visits to the river resulted in a mass of drawings of the cranes and wharves of the Port of London and Bankside. Rotherhithe from Wapping was painted in 1946 and a three-colour lithograph of the same composition followed two years later, renamed Thames-side.

The flattened perspective in this pictures embraces barges in the foreground and the jumble of warehouses on the far bank in the background. Typically, this image includes a pair of male figures in intimate conversation. Minton’s sexuality was central to his work and these dockland images embody the frustration he felt as a gay man at a time when sex between men was illegal. The many hours that Minton spent haunting the riverside allowed him not only to draw but to enjoy the company of sailors and dockers. Time and again, his pictures feature solitary male figures or distant pairs, huddled together, walking at low tide or working on boats, dwarfed by the surrounding buildings and brooding clouds.

John Minton’s only commission for London Transport came from publicity officer, Harold F. Hutchison in the form of a ‘pair poster’ titled London’s River. This concept involved posters designed in adjoining pairs, with one side featuring a striking pictorial image and the other containing text. The familiar dockland images are reworked here in gouache, in similar manner to the series of paintings commissioned for Lilliput in July 1947, London River.

An unpublished rough cover design for The Leader magazine executed in 1948 features another of Minton’s favourite motifs, the elevated street view. In this instance, the foreground figure gazing from an upper window bears more than a passing resemblance to the artist himself. The composition takes us beyond the streets below to the Thames via the dome of St Paul’s. A similar view, this time of the author’s native Hackney, graces the dust jacket of Roland Camberton’s Rain on the Pavements, published in 1951 by John Lehmann. This was the second of Camberton’s two novels, both with dust jackets designed by Minton, and tells the story of David Hirsch’s early years growing up in Hackney Jewish society.

In his 2008 article Man in a MacIntosh, Iain Sinclair followed in the footsteps of a fellow Hackney writer, recognising, “Camberton, in choosing to set ‘Rain on the Pavements’ in Hackney, was composing his own obituary. Blackshirt demagogues, the spectre of Oswald Mosley’s legions, stalk Ridley Rd Market while the exiled author ransacks his memory for an affectionate and exasperated account of an orthodox community in its prewar lull.”

John Minton’s magnificent jacket design draws us into that world with effortless elegance.

Rain on the Pavements, 1951

Scamp, 1950

Wapping, 1941

Bomb-damaged buildings, Poplar, 1941

Rotherhithe from Wapping, 1946

London Bridge from Cannon Street Station, 1946

London’s River, Lilliput 1947

London’s River, Lilliput 1947

London’s River, Lilliput 1947

Illustrations from Flower of Cities, 1949

London’s River: Pool of London, London Transport, 1951

The Leader, 1948

Isle of Dogs from Greenwich, 1955

Illustrations copyright © Estate of John Minton

You may also like to read about Alfred Daniels & Terry Scales who were taught by John Minton

In William Blake’s Lambeth

Glad Day in Lambeth

If you wish to visit William Blake’s Lambeth, just turn left outside Waterloo Station, walk through the market in Lower Marsh, cross Westminster Bridge Rd and follow Carlisle Lane under the railway arches. Here beneath the main line into London was once the house and garden, where William & Catherine Blake were pleased to sit naked in their apple tree.

Yet in recent years, William Blake has returned to Lambeth. Within the railway arches leading off Carlisle Lane, a large gallery of mosaics based upon his designs has been installed, evoking his fiery visions in the place where he conjured them. Ten years work by hundreds of local people have resulted in dozens of finely-wrought mosaics bringing Blake’s images into the public realm, among the warehouses and factories where they may be discovered by the passerby, just as he might have wished. Trains rumble overhead with a thunderous clamour that shakes the ancient brickwork and cars roar through these dripping arches, creating a dramatic and atmospheric environment in which to contemplate his extraordinary imagination.

On the south side of the arches is Hercules Rd, site of the William Blake Estate today, where he lived between 1790 and 1800 at 13 Hercules Buildings, a three-storey terrace house demolished in 1917. Blake passed ten productive and formative years on the south bank, that he recalled as ‘Lambeth’s vale where Jerusalem’s foundations began.’ By contrast with Westminster where he grew up, Lambeth was almost rural two hundred years ago and he enjoyed a garden with a fig tree that overlooked the grounds of the bishop’s palace. This natural element persists in the attractively secluded Archbishop’s Park on the north side of the arches in the former palace grounds.

To enter these sonorous old arches that span the urban and pastoral is to discover the resonant echo chamber of one of the greatest English poetic imaginations. When I visited I found myself alone at the heart of Lambeth yet in the presence of William Blake, and it is an experience I recommend to my readers.

‘There is a grain of sand in Lambeth that Satan cannot find”

These mosaics were created by South Bank Mosaics which is now The London School of Mosaic

You may also like to take a look