Adam Dant’s New Studio

I was delighted to visit my long-time collaborator and Spitalfields Life Contributing Cartographer Adam Dant at his beautiful new studio high up in the roof of Sandys Row, London’s oldest Ashkenazi synagogue.

For over twenty years, Adam had a studio on Redchurch St but was forced to leave when it fell foul of redevelopment yet he landed on his feet in this magnificent garret, as he explained to me last week.

‘I wanted to stay in Spitalfields because I have a sentimental attachment to the place and it is the grist to my mill, where everything starts in terms of my work. The neighbourhood has changed a lot since I moved here in 1995. Ironically, there are as many empty spaces now as when I moved here, then they were empty because everything was derelict and nobody wanted them but now nobody can afford to rent them.

I knew some of the board members at Sandys Row Synagogue and I heard that the caretaker had left several years ago, and there was a garret and the top of the building that would make an ideal artist’s studio. It is nice and quiet here, and they still have services in the synagogue.

So I wrote them some charming letters and they thought it was a good idea to have an artist in residence, and here I am. The caretaker left her bright orange wood-chip wallpaper but I prefer a more muted orange. The colour honours William of Orange, whom the first congregation came over with, and today the interior of the synagogue is painted orange and cream in recognition.

This is exactly at the boundary of Tower Hamlets and the City of London is on the other side of the road, within spitting distance. It is very odd, the rubbish does always seem to end up on this side of the street. I have nice view of Broadgate, St Mary Axe and Tower 42 which lights up with different messages at night. The pub on the corner gets a bit noisy on a Friday night and I think the caretaker here did not like that.

I moved in three yeas ago, and I have redecorated it to suit my artistic preference and moved my library of London books in. It was the hottest day of the year and I had to carry everything up the stairs. During the pandemic, it was so quiet here it was eerie but I carried on working. It was just here alone, I picked up the post and made sure all was in order at the synagogue.

Then they took the roof off the synagogue and replaced it. I was out of here for several months and my murals got damaged but I quite like it because now it looks like they were here before I came.

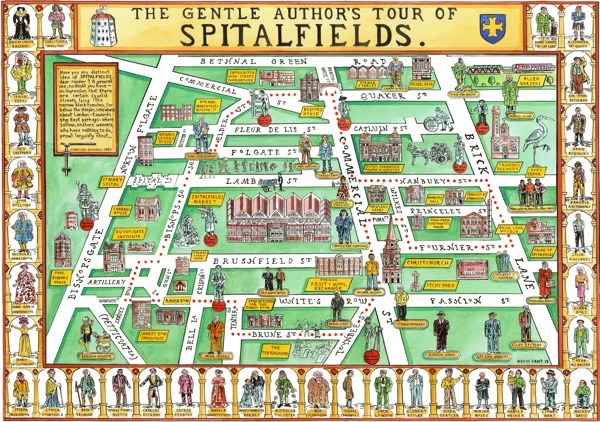

The subjects of the wall painting are my personal heroes of Spitalfields history as featured on the map of The Gentle Author’s Tour of Spitalfields. There is Christopher Marlowe with his spaniel, Mary Wollstonecraft who was born not far from here in a house by the market, Jack Sheppard who was born round the corner in Whites Row, Anna Maria Garthwaite, the eighteenth century silk designer, Nicholas Culpeper and Emilia Lanier, Shakespeare’s Dark Lady and the first woman in this country to publish a book of poems under her own name.

It is like a fancy dinner party here with guests from history around the table which is from the cellar of the synagogue, they say it is a coffin table.’

You can visit Adam’s studio as part of an open day at Sandys Row Synagogue on Sunday May 1st noon-5pm. (£5 admission charge towards the upkeep of the synagogue and East End kosher fare served. For security reasons please do not bring backpacks and large bags.)

McDonalds’ map of Rome over the fireplace

Portraits of Anna Maria Garthwaite, Christopher Marlowe and Mary Wollstonecraft.

Portraits of Emilia Lanier Bassano and Nicholas Culpeper

Click here to buy a copy of The Gentle Author’s Tour of Spitalfields Map for £5

Thanks to the magnificent generosity of over 400 people who supported our crowdfund, The Gentle Author’s Tour of Spitalfields runs throughout the summer.

There are only few tickets left at Easter and we are now taking bookings until the end of May.

BOOK YOUR TOUR AT WWW.THEGENTLEAUTHORSTOURS.COM

Adam Dant’s limited edition prints are available to purchase through TAG Fine Arts

The East London Waterworks Scandal

Nick Higham author of The Mercenary River – Private Greed, Public Good: A History of London’s Water reveals a salient lesson from history, warning of the dangers of privatised water companies who invariably put profit above safety.

The largest cylinder ever made for a water-pumping engine, 1849 (courtesy of London Museum of Water & Steam)

Take a walk along the banks of the River Lea in the shadow of the Olympic stadium and your gaze might land on a collection of ancient pipes straddling the river, graffitied and begrimed. They look out of place beside the manicured lawns and landscaped pathways of the Olympic Park.

These pipes are all that remain of a waterworks on which hundreds of thousands of East Enders once depended for almost a century and which, in London’s last cholera outbreak in 1866, was responsible for the deaths of nearly 3,800 people.

The East London Waterworks was first set up at Old Ford in 1806. It was one of a raft of new water companies founded in east, west and south London to serve the expanding metropolis, and one of the more ramshackle. Its engineer was fired before he had laid a yard of water main. Its chairman was forced to resign following an insider share trading scandal and later fled the country when it was revealed that he had also embezzled thousands of pounds of public money. Later members of the board included Joseph Merceron, a corrupt magistrate and slum landlord dubbed the ‘Boss of Bethnal Green.’

Towards the end of its life, the company struggled to get enough water from the Lea to keep the East End supplied. It had to build an eighteen-mile pipeline to bring water from the Thames at Hanworth in the eighteen-sixties and large storage reservoirs in the Lea valley – now Walthamstow Wetlands – where a couple of the company’s old pumping stations still loom over the waterfowl. Even those measures proved insufficient in a series of droughts in the eighteen-eighties and nineties when the company had to ration water.

The East London Waterworks, one of eight private London water companies, was not all bad. In 1829, it recruited the young Thomas Wicksteed as its chief engineer and he introduced the latest high-pressure steam pumping engines developed for use in Cornwall’s mines. These engines were more than twice as powerful as the previous generation of steam-driven pumps built by the Birmingham partnership of Boulton & Watt and two-thirds more efficient. A handful survive and have been restored, massive constructions of cast iron and brass. You can see them at work at the London Museum of Water & Steam at Kew Bridge.

The East London Waterworks was also a pioneer of ‘constant supply.’ Originally, water in London was delivered only a few hours every two or three days. Turncocks toured, turning the water on and off street by street. In the eighteen-fifties, the East London Waterworks was the first to take on the challenge of keeping its mains charged permanently so water was always available to customers at the turn of a tap.

But the 1866 cholera outbreak marked a low point in the company’s history. In the eighteen-forties and fifties, the tidal reaches of the River Lea had become increasingly tainted with sewage and toxic discharges. Prompted by legislation, the company moved its intake upriver to Lea Bridge, beyond the reach of the tide. There it installed filter beds to purify its water – today the beds have been left to run wild, part sculpture park, part nature reserve.

But the water from Lea Bridge still entered a covered aqueduct leading down to the company’s original reservoirs at Old Ford, from which it was pumped into the mains. Somehow the water in these holding tanks became tainted with cholera.

There are several possible explanations. One was contamination from sewage discharges upstream, perhaps from new houses built as homes for the 1,500 employees at the government’s arms factory at Enfield. Another was that water from the polluted river was seeping through the walls of the reservoirs at Old Ford. It was a problem made worse by the fact that this was the last place where London’s magnificent new sewerage system by Joseph Bazalgette was not yet finished and untreated sewage still poured into the Lea.

Yet an official inquiry established the likeliest cause of the contamination was negligence on the part of Wicksteed’s successor as chief engineer who allowed his foreman, on a nod and a wink, to top up the Old Ford reservoirs – illegally – with unfiltered water when supplies ran short.

Not everyone accepted that the company’s water was to blame. Even though official statistics showed that ninety per cent of those who died from the cholera were in the East London Waterworks’ area. Many – including several medical officers of health in the East End – refused to accept the findings of Dr John Snow, published before his death in 1858, that cholera was a waterborne disease.

The City of London’s medical officer insisted the water could not be the cause because he had analysed it and found it free of impurities, but he was also on the East London Waterworks’ payroll.

The company’s directors appear – from the minutes of their meetings – to have been blithely unperturbed by the revelation that their service might be killing the customers. They scarcely discussed the issue, and contented themselves with passively approving whatever steps their engineer took in response to the outbreak. It was not an untypical response from the capitalists of the era. This was one reason why the East London Waterworks disappeared in 1904, when with all the London water companies were taken over by the publicly-owned Metropolitan Water Board. The shareholders were richly rewarded.

Today, London’s water is again in private hands and campaigners report that the Lea is contaminated by discharges of untreated sewage.

The pipes that brought the cholera to the East End, still in use today

East London Waterwoks Coppermills pumping station in Walthamstow

East London Waterworks manhole cover at the junction of Old St and Hoxton St

Announcement of water shortage, 1896

Thomas Wicksteed’s drawing of a Cornish high-pressure steam pumping engine (courtesy of London Museum of Water & Steam)

You may also like to read about

At The Charterhouse

Brick buildings of 1531 in Preacher’s Court with the Barbican beyond

Desirous of an excuse to view the magnificence of the Charterhouse, I made a call upon my friend Brother Hilary Haydon one sunny afternoon, using the excuse of undertaking a photoessay, and these pictures – interspersed with lantern slides from the Bishopsgate Institute of the same subject a century ago – are the result.

Hilary is also enamoured by the atmosphere of repose conjured by the ancient buildings and lush gardens at the Charterhouse. “I must say, it is very pleasant to relax here and leave those fellows over in the City doing all that stressful hard work,” he confessed to me, now happily retired and enjoying the peace and quiet, after a long career as a Barrister in the Square Mile.

Carved details of the Gatehouse and the Physician’s House, 1716

Gateway of c1400 with Physician’s House built above in 1716

Cloisters in Preacher’s Court

The Preacher’s House built in the eighteen-twenties

Old pump in Preacher’s Court

Tudor chimneys in Preacher’s Court

The Great Staircase, erected in early seventeenth century and destroyed in 1941

Wash House Court

Passageway into Wash House Court

Master’s Court built in 1546

Great Hall built by Thomas Howard in 1571 while under house arrest here for plotting with Mary Queen of Scots to depose Elizabeth I

Portrait of Thomas Sutton in the Great Hall with Thomas Fenner below

Portrait of Elizabeth Salter attributed to Hogarth in the Great Hall

Chapel Cloister

Chapel Cloister

Tomb of Thomas Sutton, the founder of the Charterhouse

Thomas Sutton

The fifteenth century South Aisle of the Chapel

Brother Hilary Haydon in the North Aisle of the Chapel, added in 1614

Names of Charterhouse schoolboys etched upon the glass in the nineteenth century

Tudor brickwork upon the exterior of Wash House Court

Physician’s House built in 1716

Entrance to the Charterhouse viewed through the former Priory Gate

Knocker upon the main gate

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

A Walk Along The Black Path

‘Whan that Aprille with his shoures sote… Than longen folk to goon on pilgrimages’

Taking to heart the observation by the celebrated poet & resident of Aldgate, Geoffrey Chaucer, that April is the time for pilgrimages, I set out for day’s walk in the sunshine along the ancient Black Path from Walthamstow to Shoreditch. The route of this primeval footpath is still visible upon the map of the East End today, as if someone had taken a crayon and scrawled a diagonal line across the grid of the modern street plan. There is no formal map of the Black Path yet any keen walker with a sense of direction may follow it as I did.

The Black Path links with Old St in one direction and extends beyond Walthamstow in the other, tracing a trajectory between Shoreditch Church and the crossing of the River Lea at Clapton. Sometimes called the Porter’s Way, this was the route cattle were driven to Smithfield and the path used by smallholders taking produce to Spitalfields Market. Sometimes also called the Templars’ Way, it links the thirteenth century St Augustine’s Tower on land once owned by Knights Templar in Hackney with the Priory of St John in Clerkenwell where they had their headquarters.

No-one knows how old the Black Path is or why it has this name, but it once traversed open country before the roads existed. These days the path is black because it has a covering of asphalt.

On the warmest day of spring I took the train from Liverpool St Station up to Walthamstow to commence my walk, seeking respite in the sunshine. In observance of custom, I commenced my pilgrimage at an inn, setting out from The Bell and following the winding road through Walthamstow to the market. A tavern by this name has stood at Bell Corner for centuries and the street that leads southwest from it, once known as Green Leaf Lane, reveals its ancient origin in its curves that trace the contours of the land.

Struggling to resist the delights of pie & mash and magnificent 99p shops, I felt like Bunyan’s pilgrim avoiding the temptations of Vanity Fair as I wandered through Walthamstow Market which extends for a mile down the High St to St James, gradually sloping away down towards the marshes. Here I turned left onto St James St itself before following Station Rd and then weaving southwest through late nineteenth century terraces, sprawling over the incline, to emerge at the level of the Walthamstow Marshes.

Then I walked along Markhouse Avenue which leads into Argall Industrial Estate, traversed by a narrow footpath enclosed with high steel fences on each side. Here you may find Allied Bakeries, Bates Laundry and evangelical churches including Deliverance Outreach Mission, Praise Harvest Community Church, Celestial Church of Christ, Mountain of Fire & Miracle Ministries and Christ United Ministries, revealing that religion may be counted as an industry in this location.

Crossing an old railway bridge and a broad tributary of the River Lea brought me onto the Leyton Marshes where I was surrounded by leaves unfurling, buds popping and blossom exploding – natural wonders that characterise the rush of spring at this sublime moment of the year. Horses graze on the marshes and the dense blackthorn hedge which lines the footpath provided a sufficiently bucolic background to evoke a sense that I was walking an ancient footpath through a rural landscape. Yet already the municipal parks department were out, unable to resist taking advantage of the sunlight to give the verges a fierce trim with their mechanical mower even before the the plants have properly sprouted.

It was a surprise to find myself amidst the busy traffic again as I crossed the Lea Bridge and found myself back in the East End, of which the River Lea is its eastern boundary. The position of this crossing – once a ford, then a ferry and finally a bridge – defines the route of the Black Path, tracing a line due southwest from here.

I followed the diagonal path bisecting the well-kept lawn of Millfields and walked up Powerscroft Rd to arrive in the heart of Hackney at St Augustine’s Tower, built in 1292 and a major landmark upon my route. Yet I did not want to absorb the chaos of this crossroads where so many routes meet at the top of Mare St, instead I walked quickly past the Town Hall and picked up the quiet footpath next to the museum known as Hackney Grove. This byway has always fascinated me, leading under the railway line to emerge onto London Fields.

The drovers once could graze their cattle, sheep and geese overnight on this common land before setting off at dawn for Smithfield Market, a practice recalled today in the names of Sheep Lane and the Cat & Mutton pub. The curve of Broadway Market leading through Goldsmith’s Row down to Columbia Rd reveals its origin as a cattle track. From the west end of Columbia Rd, it was a short walk along Virginia Rd on the northern side of the Boundary Estate to arrive at my destination, Shoreditch Church.

If I chose to follow ancient pathways further, I could have walked west along Old St towards Bath, north up the Kingsland Rd to York, east along the Roman Rd towards Colchester or south down Bishopsgate to the City of London. But flushed and footweary after my six mile hike in the heat of the sun, I was grateful to return home to Spitalfields and put my feet up in the shade of the house. For millennia, when it was the sole route, countless numbers travelled along the old Black Path from Walthamstow to Shoreditch, but on that day there was just me on my solitary pilgrimage.

At Bell Corner, Walthamstow

‘Fellowship is Life’

Two quinces for £1.50 in Walthamstow Market

Walthamstow Market is a mile long

‘struggling to resist the delights of pie & mash’

At St James St

Station Rd

‘leaves unfurling, buds popping and blossom exploding which characterise the rush of spring’

Enclosed path through Argall Industrial Estate skirting Allied Bakeries

Argall Avenue

‘These days the path is black because it has a covering of asphalt’

Railway bridge leading to the Leyton marshes

A tributary of the River Lea

Horses graze on the Leyton marshes

“dense blackthorn which line the footpath provided a sufficiently bucolic background to evoke a sense that I was walking an ancient footpath”

‘the municipal parks department were out, unable to resist taking advantage of the sunlight to give the verges a fierce trim with their mechanical mower even before the the plants have properly sprouted’

The River Lea is the eastern boundary of the East End

Across Millfields Park towards Powerscroft Rd

Thirteenth century St Augustine’s Tower in Hackney

Worn steps in Hackney Grove

In London Fields

At Cat & Mutton Bridge, Broadway Market

Columbia Rd

St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch

You may also like to read about

Jeffrey Johnson’s Favourite Signs

Enigmatic Photographer Jeffrey Johnson deposited a stack of his pictures from the seventies and eighties with Archivist Stefan Dickers at the Bishopsgate Institute, including these photos of signs and ghost signs. Sharing Jeffrey’s relish at this magnificent array, I cannot resist the feeling that he is one after my own heart in savouring both the poetry and aesthetics of London’s old signage.

Win her affections with A1 Confections

Temporary office staff urgently required

Permanent waving clubs held here

More news than in any other daily paper

English clock system

Barry Lampert – Your choice for Hackney

The best food for the whole family sold here

Home cured haddocks & bloaters

The noted house for paper bags

£40 worth for four shillings weekly

Families and dealers supplied

Harris the sign king

Headache draughts

Progressive working class catering

For that natural just combed look

Radio London wireless said ‘The cosy fish bar in Whitecross St serves the best quality fish & chips in London.’

See the light…taste the light

We specialies in suits, donkey coats, officers uniforms, belts & braces, sailors clothing…

Laying out & measuring up undertaken

Photographs copyright © Jeffrey Johnson

You may also like to took at

Sally Flood, Poet

“I think my life is more in poetry than anything else”

“I had always written, as a child,” admitted Sally Flood with a shrug, “but it wasn’t stuff you showed.” In the years when her thoughts wandered whilst working in the factory in Princelet St, Sally wrote poems on the paper that backed the embroidery in the machine she operated – but she always tore up her compositions when her boss appeared.

Then, when she was fifty years old, Sally took some of her poems along to the Basement Writers in Cable St and achieved unexpected recognition, giving her the confidence to call herself a poet for the first time. Since then, Sally’s verse has been widely published, studied in schools and universities, and she has become an experienced performer of her own poetry. “At work, I used to write things to make people laugh,” she explained, “I used to say, ‘Embroidery is my trade, but writing is my hobby.'”

“I’ve got drawers full of poems,” she confided to me with a blush, unable to keep track of her prolific writing, now that poetry is her primary occupation and she no longer tears up her compositions. “I’ve got so much here, I don’t know what I’ve got,” she said, rolling her eyes at the craziness of it.

Ambulance helicopters whirl over Sally’s house, night and day, the last in a Georgian terrace which is so close to the hospital in Whitechapel that if you got out of bed on the wrong side you might find yourself in surgery. Sally moved there more than half a century ago with her young family, and now she has three grandchildren and five great grandchildren. Framed pictures attest to the family life which filled this house for so many years, while today boxes of toys lie around awaiting visits by the youngest members of her clan.

“In 1975, when my children were growing up and the youngest was fifteen, I decided that I need to do something else, because I didn’t want to be one of those mothers who held onto her children too much.” Sally recalled, “So I joined the Bethnal Green Institute, and it was all ballroom dancing and keep fit, but I found a leaflet Chris Searle had put there for the Basement Writers, so I decided to write a poem and send it along to them. Then I got a letter back asking me to send more – and I was amazed because the poem I sent was one I would otherwise have torn up. Of your own work, you’ve got no real opinion.”

“On my first visit, I went along with my daughter, but there were children of school age and I was turning fifty. I wasn’t sure if I should be there until I met Gladys McGee who was ten years older than me. She was so funny, I learnt so much from her – she had been an unmarried mother in the Land Army. I started going regular, and the first poem I read was published.”

“I think my life is more in poetry than anything else. I sometimes think my writing is like a diary. Chris Searle of the basement writers made such an impression on my life, he gave me the confidence to do this. And when I did my writing, my life took off in a certain direction and I met so many fantastic people.”

Sally’s house is full of cupboards and cabinets filled of files of poems and pictures and embroidery, and the former yard at the back has become a garden with luscious fuchias that are Sally’s favourites. After all these years of activity, it has become her private space for reflection. Sally can now get up when she pleases and enjoy a jam sandwich for breakfast. She can make paintings and tend her garden, and write more poems. The house is full with her thoughts and her memories.

“My grandparents were from Russia and they brought my father over when he was four years old.” Sally told me, taking down the photograph to remind herself, “He became cabinet maker and he was one of the best. In those days, they used to work from six until ten at night, so they knew what work was. I was born in Chambord St, Brick Lane, in 1925, and I grew up there. From there we moved to a two-up two-down in Chicksand St and from there to Bethnal Green, just before the war broke out. We had a bath in the kitchen with a tabletop. It was the first time we had a bath, before that we went to bathhouse. I’m telling you the history of the East End here!

I was evacuated to Norfolk at first. We took the surname Morris from father’s first name, so that people wouldn’t know we were Jewish. The people up there had a suspicion against Londoners and they thought we were all the same. But I was lucky, we ended up in a hotel on the river in Torbay in Devon. Life was fantastic, we used to go fishing. It was a different experience from my life in London. I joined the girl guides, I could never have done that otherwise. Where I was evacuated, they wanted to train me to be a teacher, but my mother came and took me back and said, “They’re going to exploit you, you’re going to be a machinist.”

“Being evacuated meant I went outside my culture, and I saw that English people were nice. I think that’s why I married outside my religion. We were together fifty-five years and I always say it wasn’t enough. If I hadn’t been evacuated I wouldn’t have done that.”

Sally put the photograph of her parents back on the shelf carefully, and turned her head to the pictures of her husband, her children, her grandchildren and great-grandchildren, on different sides of the room. I watched her looking back and forth through time, and the room she inhabited became a charged space in between the past and the future. This is the space where she does her writing. And then Sally brought out a book to show me, opening it to reveal it short poems in her handwriting accompanied by lively drawings of people, reminiscent of the sketches of L. S. Lowry or the doodles of Stevie Smith.

Sally is a paradoxical person. A natural writer who resists complacency, she continues to be surprised by her own work, yet she is knowledgeable of literature and an experienced teacher of writing. Appearing at the door in her apron and talking in her tender sing-song voice, Sally wears her erudition lightly, but it does not mean that she is not serious. With innate dignity and a vast repertoire of stories to tell, Sally Flood is a writer who always speaks from the truth of her experience.

Maurice Grodinsky, Sally’s father is on the left with Sally’s mother, Annie Grodinsky, on the right, and Freda, Maurice’s mother, in between. At four years old, Maurice was brought to Spitalfields from Bessarabia at the end of the nineteenth century. The two children are Marie and Joey – when this picture was taken in 1925, Sally was yet to be born.

Sally with her first child Danny in the early nineteen fifties.

Sally’s children, Maureen, Jimmy, Pat and Theresa in the yard in Whitechapel in 1962.

Sally’s husband, Joseph Flood.

Sally in Whitechapel, early sixties.

Sally with her children, Danny, Theresa, Jimmy, Maureen, Pat and Michael.

Sitting by the canal in the nineteen seventies.

Sally with Gladys McGee at the Basement Writers.

You may also like to read about

Val Perrin’s Brick Lane

Photography has been a lifetime’s hobby for Val Perrin. Yet it is apparent from this selection of his pictures of Brick Lane Market, taken between 1970-72, that he possesses a vision and ability which bears comparison with the Magnum photographers whose work he admired at that time.

While studying Medicine at University College, London, Val visited East End markets with members of the University Photographic Club, but Brick Lane drew his attention. Over the next two years, he returned alone and with fellow students, with whom he shared a flat in West Dulwich, to document the vibrant market life and surroundings of Brick Lane.

Born in Edgware, Val moved to live near Cambridge in 1976 and now photographs mainly wildlife and landscapes, but the eloquent collection of around a hundred photographs he took of Brick Lane in the early seventies comprises a significant and distinctive record of a lost era.

Photographs copyright © Val Perrin

You also might like to take a look at