Rob Ryan & The East End Trades Guild

Tickets are available for my Spitalfields tour throughout October & November

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

by Rob Ryan

As one of those who conjured the EAST END TRADES GUILD into existence back in November 2012 to advocate for the interests of local small businesses, I am beyond proud to announce the tenth anniversary of the founding of the Guild. During such challenging times for independent enterprises, its role is more vital than ever.

In celebration of such an auspicious moment, the Guild have commissioned ROB RYAN to design this year’s map of East End traders which will be available free from all members on Small Business Saturday 3rd December.

Your deadline to join the Guild and be featured on the map is Monday 10th October. Small businesses, independent shops, social enterprises, charities and self-employed people can join.

CLICK HERE TO JOIN THE EAST END TRADES GUILD

All members will be invited to our huge tenth anniversary party for the East End Trades Guild on 23rd November at the Bishopsgate Institute which will include a presentation by yours truly, and Paul Gardner promises to wear a suit.

I shall be hosting East End Trades Guild walks around Spitalfields on Small Business Saturday, revealing the diverse histories of the shops that make the place and telling the story of the origins of the Guild here in London’s traditional heartland for small traders and independent endeavours.

The founding of the East End Trades Guild in 2012 photographed by Martin Osborne

Paul Gardner, Paper Bag Baron & Founder of the East End Trades Guild

Symbol of the East End Trades Guild designed by James Brown, 2012

You may also like the read about

The Founding of the East End Trades Guild

Frank Merton Atkins’ City Churches

Tickets are available for my Spitalfields tour tomorrow and through October

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Christ Church, Spitalfields, 1 October 1957

A collection of photographs by Frank Merton Atkins – including these splendid pictures of City churches were donated to the Bishopsgate Institute by his daughter Enid Ghent who had kept them in her loft since he died in 1964.

‘My father worked as a cartographer for a company of civil engineers in Westminster and he drew maps of tram lines,’ Enid recalled, ‘Both his parents were artists and he carried a camera everywhere. He loved to photograph old pubs, especially those that were about to be demolished. Sometimes he got up early in the morning to take photographs before work and at other times he went out on photography excursions in his lunch break. He was always looking around for photographs.’

Captions by Frank Merton Atkins

All Hallows Staining Tower, 25 June 1957, 1.22pm

Cannon Street, looking west from corner of Bush Lane, 7 June 1957, 8.21am

St Botolph Aldgate, from Minories, 31 May 1960, 1.48pm

St Bride from Carter Lane, 31 May 1956, 8.20am

St Clement Danes Church, Strand, from Aldwych, 14 October 1958, 1.22pm

St Dunstan in the East (seen from pavement in front of Custom House), 13 June 1956, 1.14pm

St George Southwark, from Borough High Street, 14 August 1956, 8.15am

St James Garlickhithe, from Queenhithe, 20 May 1957, 8.23am

St Katherine Creechurch, 27 May 1957, 8.32am

St Magnus the Martyr, from the North, 26 June 1956, 8.17am

St Magnus the Martyr, Lower Thames Street, 26 June 1956, 8.23am

St Margaret Lothbury, 2 August 1957, 1.12pm

St Margaret Pattens, from St Mary At Hill, 13 June 1956, 1pm

St Mary Woolnoth, 8 August 1956, 5.49pm

St Pauls Church, Dock Street, Whitechapel, 3 September 1957, 1.09pm

St Pauls and St Augustine from Watling Street, 7 May 1957, 8.25am

St Vedast, from Wood Street, 30 July 1956, 8.17am

Photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to look at

The Return Of Sue Hadley

Tickets are available for my tour of Spitalfields THIS SATURDAY 1st OCTOBER

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Sue Hadley returned recently for an afternoon to revisit some of her childhood haunts and I had the privilege of accompanying her.

“From the age of three, I grew up here in James Hammett House on the Dorset Estate in Bethnal Green. It was a good old Labour council and each of the buildings was named after one of the Tolpuddle Martyrs. Architecturally they are quite special, designed by the Tecton partnership. I used to slide all the way down the handrail of the spiral staircase, which is similar to the one they did for the penguin pool at the Zoo. We lived at the top of the building, on the tenth floor, and we were the very first residents to move in in 1957. But I stayed up at the top, I was not allowed to come down and play for many years – which was a disappointment. Once I was old enough to be allowed down, then the whole of the estate was my playground. Mum was a machinist working from home and Dad was a leaded light maker working in the Kingsland Rd.”

Sue on the balcony at James Hammett House

“This is Jones Dairy where I used to come with my Mum to do our shopping – cornflakes and tins. It was a proper traditional grocer with a man behind the counter in a white coat, Mr Evans. If you asked for a packet of cornflakes, he would get out his stick and stretch up to the shelf for it. My Mum was uncomfortable shopping here because she did not like people to know what she was buying.”

“At four years old, I started nursery school here at Columbia Rd School. I could see it from my house and I used to walk to school once I was old enough. It was a good school and I had a good education. The East End was being elevated then and we were lucky to have some excellent teachers. It was quite disciplined and I got told off once for being late for morning assembly. I got in with two children who said, ‘Shall we go to the sweetshop and buy sweets instead?’ So I spent my sixpence pocket money on sweets and then I went to school and I got told off. I was placed in front of everyone in the hall and my wrist was slapped several times as punishment. I wasn’t too riotous, I think I was quite academic. English and Art were my best subjects. I still have one long-standing friend, Carol, who I met here. My parents were completely thrilled when I got a place at Central Foundation School and I left at twelve.”

“Round the corner from us was a bomb site known as ‘the black buildings.’ Subsequently, I found out it was the Columbia Rd Market founded by Angela Burdett Coutts. It was an open bomb site and the most dangerous of places to play. We used to dare each other to go in because it was so creepy. There were dead cats and boys threw things at you. It was a place of mayhem but it was fun.”

“When I was eight years old, my sister who was twelve years older than me, got married here at Shoreditch Church. My Mum made the bridesmaid dresses but my sister splashed out on a proper bridal dress from Stoke Newington. It must have been quite a stretch because my sister paid for most of her own wedding. She still has all the original receipts! I remember thinking how boring the service was, it just seemed to go on for ever and ever. They went on honeymoon to Canvey Island. It was a successful marriage, they were married almost sixty years until she lost her husband last year.”

Sue stands central as bridesmaid at the wedding of her sister Barbara to Ron

“When I was a kid, the most exciting thing to do on a Sunday was to come here to Sclater St with my Dad. He would buy sensible things like boxes of broken biscuits and tins with no labels on, he was quite a cheapskate. Afterwards, I would drag him down here to the shops with birds in cages. There was donkey for sale here once and people brought their puppies to sell. It was all a bit dodgy which was why they shut it down eventually. However, for me it was the most exciting thing because I could play with the puppies and kittens although I never got to own one. We always had a budgie at home, it was always called ‘Jackie’ because we had a succession of them. We didn’t keep it in the cage, our bird was free the fly around the flat. Some escaped.”

“Central Foundation School For Girls was prestigious and I had the best education, with the broadest range of subjects. It was the time of the equal rights movement and our teachers were quite right on. The hall was where we did sports and I remember playing volley-ball and smashing one of the lights. I did fencing and my teacher was in the Olympic team, she did well.

I was completely daft because I got engaged at fifteen when I was still at school. Although the world was moving on, in the East End we never quite got it. My parents’ aspiration for me was that I should not work in a factory, so I worked in an office. I left school and went to work at Central Electricity Board in Newgate St as a copy typist. It was clean, it was a step up. I also got married and moved to Gravesend, but it all fell apart after two years because I hated being away from London. I felt like a fish out of water and I came back. When I walk these streets, I feel like I belong.

Ten years ago, I became a Blue Badge Guide. I have always been interested in history, so I did an Open University degree at forty. I have Huguenot ancestry and am descended from Sarah Marchant who was buried in Christ Church, Spitalfields, in the eighteenth century.

It all came good for me in the end because I have so much knowledge in my head and it really helps me doing my guiding. I love it.”

Sue in the fencing team at Central Foundation School for Girls

You may also like to take a look at

Adam Dant, Cartographer Extraordinaire

Tickets are available for my tour of Spitalfields THIS SATURDAY 1st OCTOBER

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

The Gentle Author’s Tour Of Spitalfields

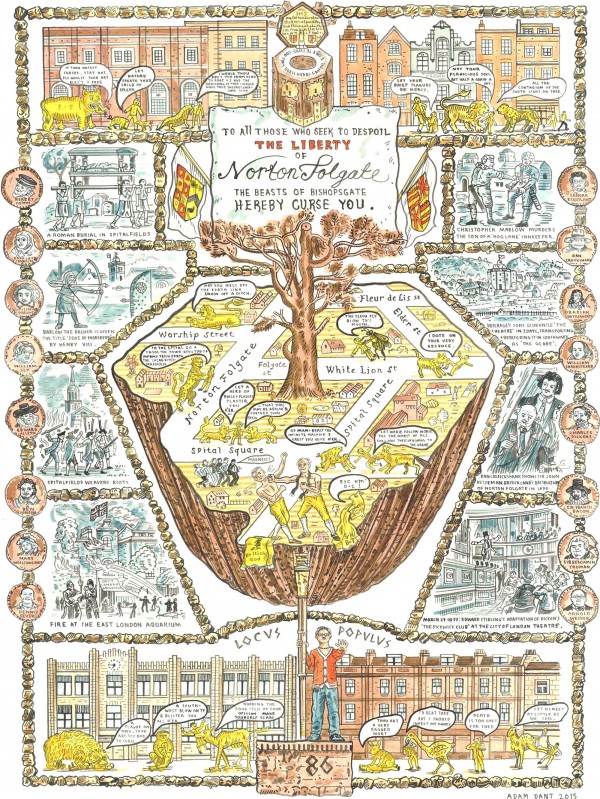

Cartographer Extraordinaire ADAM DANT opens the series of eight SPITALFIELDS TALKS I have curated with the Spitalfields Society at the Hanbury Hall in Hanbury St, next Tuesday 4th October at 6:30pm. Adam will be showing a selection of his maps including some of those in his new book, Adam Dant’s Political Maps published by Batsford.

Click here to book your ticket for Adam Dant’s talk for £6

Talks take place on the first Tuesday of each month, running through the winter into next spring. Readers are encouraged to buy season tickets at £35 available from Spitalfields Society.

The Map of Spitalfields Life

The Map of the Coffee Houses

The Map of Shoreditch as the globe

The Map of Shoreditch as New York

The Map of Shoreditch in the year 3000

The Hackney Treasure Map

The Map of Industrious Shoreditch

The Map of Wallbrook

The Map of Norton Folgate

The Map of William Shakespeare’s Shordiche

The Map of Thames Shipwrecks

Maps copyright © Adam Dant

Prints of Adam Dant’s maps are available from TAG Fine Arts

You may like to take a look at the whole series of talks

A Flight In A 1939 Tiger Moth

Tickets are available for my tour of Spitalfields this Saturday 1st October

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

What better way could there be to enjoy a warm September afternoon than taking a gentle spin in a 1939 Tiger Moth over Kent? I took off from Damyns Hall Aerodrome in Upminster where the East End pilots of World War Two did their training in exactly such a plane.

A train delivered me to Upminster, then a bus dropped me at Corbets Tey before I walked a mile along the grass verge towards Aveley. Strolling up an unremarkable farm track, I discovered a number of brightly coloured vintage aeroplanes and there, ahead of me, stretched a wide expanse of grass that serves as the runway.

My pilot Alex Reynier – the model of confident expertise in a sleek flight suit – was waiting in the clubhouse and, once I had signed a one day membership of the flying club, we walked out to survey the bright red Tiger Moth – as jaunty as a model plane.

These vehicles were used for pilot training – with two seats, one behind the other, open cockpits and dual controls. The robust simplicity of the vehicle is awe-inspiring, essentially a large kite with a motor engine attached. The wings are made of cloth stretched over a frame and the light-weight body of aluminium. Alex opened up the hood to reveal the engine, fitted upside-down to ensure that oil always reaches the pistons and it cannot stall.

I pulled the nozzle out of the nearby petrol pump and handed it Alex so he could fill the small overhead fuel tank, situated where the wings met. Wrapped in some extra layers for warmth, I climbed into my tiny cockpit then Alex strapped me in and fitted my headphones and microphone so we could communicate in the air.

After such a dry summer, the runway was bumpy but fortunately we did not discover any new rabbit holes and the tiny plane took off effortlessly into the sky, spiralling up at an astonishing speed into the rushing wind.

It is impossible not to be overwhelmed at first by the visceral experience of flight when you are exposed to the air without any barrier between you and the sky. You gaze down from the familiar height of an aeroplane, yet without any of the barriers that are designed to insulate you from the reality of flight in commercial airlines, especially the racing currents of wind and the vibration of the motor. In a Tiger Moth, you are seemingly suspended in air, like an insect.

We were high over the Dartford Bridge, so I turned my head right to see London and left to see the Thames estuary. Without direct reference, the sense of speed was indeterminate.

I was delighted and reassured to be reminded how green the landscape is, mostly undeveloped fields and woods, still peppered with fine old houses and castles – picture book England. Alex pointed out Eynsford Castle, Lullingstone Castle, Chavening House and Chartwell. At Chavening, we descended in a cheeky spiral around the house to take a nosy peek at the gardens. But the climax of the flight was to circle over Knole, just outside Sevenoaks. This is one of my favourite places and the house is often described as resembling a medieval city on account of its vast rambling structure, yet it appeared like a model that I could reach out and pick up if I chose.

Indeed I was beginning to feel that – from above – the world looked like a model of itself, the work of a fanatical enthusiast. This realisation engenders a seductive sense of powerful autonomy, encouraging the notion that it is all laid out from your pleasure and you can fly wherever you please upon a whim. Such was my exhilarated reverie, suspended at 1800 feet over Kent.

I discovered that in these tiny open planes, which take you so high into the air so quickly, the experience of flight has less mystique but a lot more wonder.

Knole

The Thames

Landing safe and sound at Damyns Hall Aerodrome

Geoff Perrior’s Spitalfields

Tickets are available for my tour of Spitalfields throughout October & November

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Geoff Perrior

This small cache of Geoff Perrior’s photographs of Spitalfields taken in the nineteen-seventies was deposited at the Bishopsgate Institute Library by his widow Betty Perrior. Fascinated to learn more of the man behind these pictures, I spoke with Betty in Brentwood where she and Geoff lived happily for forty-two years.

“He was a character,” she recalled fondly, “he belonged to eight different societies and he was a member of the Brentwood Photography Club for fifty-three years, becoming Secretary and then President.”

“He started off with a little Voightlander camera when he was a youngster, but he graduated to a Canon and eventually a Nikon. He said to me, ‘I can afford the body of the Canon and I’ll buy a lens and pay for it over a year.’ Then he sold it and bought a Nikon. He only switched to digital reluctantly because he thought it was rubbish, yet he came round to it in the end. For twenty years, we did all our own developing in black and white.

Geoff & I met at WH Smith. I had worked at WH Smith in Salisbury for twelve years before I went on a staff training course at Hambleden House in Kensington and Geoff was there. We just clicked. That was in July, we were engaged in October and married a year later. I was forty-four and we were both devoted, my only regret is that we had just forty-two years together.

Geoff worked for WH Smith for thirty-seven years and for thirty years he was Newspaper Manager at Liverpool St Station, but he never took photographs in the station because it was private property. He used to do the photography after he had done the early shift. He got up at three-thirty in the morning to go to work and he finished at midday. Then he went down to Spitalfields. One of the chaps by the bonfire called out to him, ‘I love this life!’ and, one day, Geoffrey was about to take out ten pounds from his wallet and give it to one of them, when the vicar came by and said, ‘Don’t do that, they’ll only spend it on meths – buy him a dozen buns instead.’

Geoff had a rapport with anybody and everybody, and more than two hundred people turned up to his funeral. I have given most of Geoff’s pictures away to charity shops and they always sell really quickly, I have just kept a selection of favourites for myself – to remind me of him.”

Geoff Perrior

Sitting by the bonfire in Brushfield St

“Got a light, Tosh?”

In Brushfield St

In Toynbee St

Spitalfields Market porter

In Brushfield St

In Petticoat Lane

In Brushfield St

In Toynbee St

In Brushfield St

In Brushfield St

Spitalfields market porter in Crispin St

In Brune St

In Brushfield St

In Brushfield St

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to take a look at

Dennis Anthony’s Petticoat Lane

Colin Ross, Docker

Tickets are available for my tour of Spitalfields throughout October & November

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Colin Ross has always been drawn to the river, though now it is the River Crouch at Hullbridge in Essex where he lives in retirement, rather than the Thames where once he and three generations of men in his family before him worked as dockers at the Royal London Dock. With his sharp bird-like features, deeply lined face, strong jaw and shock of white hair, Colin is an imposing figure with natural dignity and an open sociable manner. Above all, you sense a generosity of spirit. It is an heroic attribute in one who fought the long battles that Colin did – battles which proved to be unwinnable – to keep the docks alive and keep his fellow dockers in employment there.

Yet zeal was a quality that was never lacking in the Ross family, as demonstrated by his father Tom who was one of those who set up The Distress Fund. “There was no sickness benefit or compensation for injuries in the docks, and we had so many dockers who were dying and getting pauper’s funerals,” Colin explained, “Ten thousand people joined the fund at a shilling a week and if a docker died his widow got seventy-five pounds. The work they put in to collect that one shilling a week, but that was the kind of people East Enders were, we looked after each other.”

Similarly, Colin came up against a management that had no concern for the dockers’ welfare when manhandling sacks of asbestos. “They said it was perfectly safe,” he recalled with a frown, “and they told me I was troublemaker for objecting. But in 1967, we were the first workplace to ban it, when the union refused to touch it. I feared for the African dockers who loaded it in hessian sacks.”

Living modestly with his wife in an immaculately-kept mobile home surrounded by a small garden close to the River Crouch in Essex, Colin has found a peaceful haven and no longer comes up to London very often, but he was eager to speak to me of the conflicts surrounding the closure of the docks in which he fought with such courage and presence of mind.

“The Royal London Group of Docks was the largest enclosed docks in the world and I was the fourth generation of my family to work there – before me there was Tom, Jack and Archie, who came down from Scotland. My grandfather Jack was involved in the first great dock strike of 1889 that led to the foundation on the TGWU. The East End was absolute poverty then and the strike went on and on. Money was sent from all over the world to support the dockers. Randolph Hearst sent money, and in the end it was the intervention of the Catholic church and Cardinal Manning personally that got the ship owners to the negotiating table. My nan’s brother – his family were so destitute that his wife sold her body to make money and, when he found out after the strike, he killed her.

I joined the docks in 1965 at the age of twenty. At sixteen, I went to sea but if your dad was a docker it was expected you would work in the docks, and my dad’s reputation went before me. When you went to work, you earned good money – but most of the time you didn’t get to go to work. Jack Dash – the legendary union man – took me on one side to recruit me as union leader and said, “Son, there’s three people you want to avoid in life, ship owners, insurance agents and bankers.” I don’t think he was far off there.

People don’t realise the battles we had in our struggle to keep the docks open. We saw that containerisation was coming and we realised it was going to mash the East End to bits. There were 27,000 regulated dock workers and for every one of them another two workers dependent on the docks. 100,000 people relied on the docks for a living. We negotiated with the Port of London Authority and they said, “It’s no good standing in the way of progress.” But what’s the good of progress if it doesn’t benefit everyone? Our argument was – You have the docks in place and the rail links and the workforce, why can’t containerisation be done in the docks? Gradually, they weakened our cause with increased offers of severance pay and then, before we knew it, the asset strippers moved into the Royal London Docks – only they called them Venture Capitalists, they bought up the docks, closed them down and sold them as flats at half a million pounds each.

When I went into the docks, Charles Dickens would have recognised it. It was that antiquated because the ship owners never spent a penny on it. I thought, “Something’s wrong here,” because the shipping companies belong to the richest people in the country, and the wages were so low they could afford to keep 2,000 paid dockers in reserve to cover for the holiday period. It was the industry with the highest level of accidents in the country and you got no sick pay. The mortality rate was high and dockers did not expect to live beyond fifty-eight to sixty on average – this was in the nineteen sixties.

We never realised they were going to close down the docks until we met some American longshore men and they had experienced the same thing. But in America the union was so strong because it was run by the mafia, they got a deal we would die for. I went to Jack Jones at the TGWU and said “Can’t you see what’s happening?” We formed our own unofficial committee, the National Port Shop Stewards’ Committee. The problem was the same in Liverpool, Hull and Southampton and we decided to hold dock gate meetings. We picketed dock gates in London, saying to lorry drivers they would be blacklisted in every dock in the country if they crossed our picket line, and it was a roaring success. Ted Heath was Prime Minister at the time and they threatened to put us in prison, but they realised if they arrested us there would be carnage.

All the time we had viable propositions to keep the docks open, using the river and opening up rail links but the Port of London Authority didn’t want them. All of a sudden, five of our members were arrested and put in Pentonville Prison, so we created a picket line at the prison gate. And in my four or five days there I saw more of life than I’d seen in my life. The TUC called a General Strike in our support. All the unions, the carworkers, the steelworkers, they were with us. Our five members were released but they had smashed us. The dispute shifted from being our dispute to being a dispute about the Industrial Relations Act. The union backed me but my Dad said, “They backed you to take control, and they used it to get more severance money and send us back to work.” I knew then that the chips were down.”

In 1978, Colin Ross left the docks. He went to work at a container plant in Purfleet and his wages increased from £30 to £350 a week, but he found there was no camaraderie as he had known at the docks in the East End. Within two years, Colin left to run a fruit and vegetable at Globe Town Market Sq in the Roman Rd for the rest of his working life. “It was the saddest day of my life,” was how he described leaving dock work, after his personal history of struggle and the struggle of three generations behind him.

“We had it within our grasp to keep the docks open, they could have been working today.” he said to me, raising his hands and reaching out with visible emotion, “I’m not angry, what has happened has happened. I am not bitter but I am annoyed at how it happened. Canary Wharf may be beautiful, yet I can’t ever bring myself to go back to the docks anymore.”

The London Docks were closed by shipowners who wanted to move to new container ports as a means to break the unions and introduce casual labour, and make short-term profits by selling off their warehouse spaces. Yet the final irony lies with Colin, because anyone who has travelled upon the Thames – the silent highway, as they once called it – recognises the absurdity of the empty river when it is the obvious conduit for transport of goods as the roads grow ever more overcrowded. River transport linked to rail would be a much greener and more efficient option in the long term than the container ports and haulage trucks we are now forced to rely upon. With remarkable foresight, Colin saw all this fifty years ago and he fought his best fight to stop it happening. So although he may be disappointed his spirit is intact – and his story is an important one to remember today.

Colin made the front page of the Daily Mail in 1970.

Colin’s pass book issued by the National Dock Labour Board.

Colin’s union membership cards.

Note number six, the rate for unloading bags of Asbestos.

Colin as a Shop Steward in 1976.

Colin Ross in his garden in Hullbridge.

You may also like to read about Colin’s daughter