Last Days At W.F. Arber & Co

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKETS

Last week I learnt belatedly that my friend Gary Arber – the legendary printer of the Roman Rd – died three years ago. Here is my account of my last visit to his print works before it closed forever.

Gary Arber

Four years passed since I first walked eastward through the freshly fallen snow across Weavers’ Fields on my way to visit Gary Arber, third generation incumbent of W.F. Arber & Co Ltd, the printing works in the Roman Rd opened by Gary’s grandfather Walter Francis Arber in 1897. Captivated by this apparent time capsule of a shop where little had changed in over a century, I was tempted to believe that it would always be there, yet I also knew it could not continue for ever.

“In October, I couldn’t find enough money from my takings to pay my business rates,” Gary admitted to me then, “and that’s when I decided it was time to call it a day.” As the last in the family business, Gary had been pleasing himself for years. After three generations, the metal type was all worn out and so Gary let the machines run down, taking on less and less printing. Then he put the building up for sale and set a date that coincided with when his insurance ran out, as his date to vacate the premises.

Bearing the responsibility of being the custodian of the contents, a major question for Gary was to find a home for his collection of six printing presses which are of historic significance. He has gave them to the Cat’s Eye Press in Happisburgh, Norfolk, who agreed to restore them all to working order and put them to use again. Since he made his decision, Gary had been at work clearing up the sea of boxes and detritus that had accumulated to conceal the machines and I took advantage of this brief moment to see the presses in their glory before the process of taking them apart and transferring them to Norfolk commences later that week.

“It’s good to see them again after thirty years,” declared Gary, as he led me down the narrow staircase to the small basement print workshop where the six gleaming beasts were newly revealed from beneath the litter. In the far corner was the Wharfdale of 1900 that has not moved since it was installed brand new and, at the foot of the stairs, sat the Golding, also installed in 1900. The Wharfdale was a heavy rectangular machine that famously was used to print the Suffragettes’ posters while the more nimble Golding was employed to print their handbills. At WF Arber & Co Ltd it had not been forgotten that Gary’s grandmother Emily would not permit his grandfather to charge Mrs Pankhurst for this work.

The Heidelberg of 1939 was the last press still in full working order and Gary informed me that since World War II broke out after it was delivered, his father (also Walter Francis) had to pay the British Government for the cost of it, although he never discovered if the money was passed on to the Germans afterwards. Next to it, stood the eccentrically-shaped Lagonda of 1946 which we were informed by its future owner was believed to be the last working example in existence.

In between these two pairs, sat the big boys – two large post-war presses, a Mercedes Glockner of 1952 and Supermatic of 1950. Gazing around at these monstrous machines, sprouting pipes and spindles and knobs, Gary could recall them all working. In his mind, he could hear the fierce din and see those long-gone printers – Fred Carter, Alfie Watts, Stan Barton & Harry Harris among others – who worked there and wrote their names in pencil underneath the staircase. Sometime in the mid-fifties, alongside their names and dates, Gary wrote his name too, but instead of the date he wrote “all the time” – a statement amply confirmed by his continued presence more than half a century later.

Yet Gary never set out to be a printer. He set out to fly Lincoln Bombers, only sacrificing his life as a pilot after his father’s premature death, in order to take over the family print works. “I bought myself out in 1954, but I would be dead by now if I had stayed on, retired and grown fat like all the rest,” he confided to me, rationalising his loss, “I’m the only one surviving of my crew and I can still lift a hundredweight.”

“I remember when I first came here to visit the toy shop upstairs as a child but I didn’t get a toy except for my birthday and at Christmas,” Gary informed me, <“My grandfather always had his bowler hat on. He had two, his work bowler and his best bowler. He was a very strict and moral man, he raised money for hospitals and he was a governor of hospitals.”

We all missed WF Arber & Co Ltd, but it was far better that Gary chose to dispose of the business as it suited him, and wrapped it up to his satisfaction, than being forced into it by external circumstances. After all those years, Gary Arber could rest in the knowledge that he had fulfilled his obligation in a way that paid due respect to both the Walter Francis Arbers that preceded him.

The Wharfdale & The Glockner

The 1900 Golding that printed the Suffragettes’ handbills

The 1900 Wharfdale that printed the Suffragettes’ posters

The 1952 Mercedes Glockner

Gary was printing with this 1939 Heidelberg last week

The last known working Lagonda in the world, 1946

The 1950 Supermatic

Gary found his Uncle Albert’s helmet under one of the machines while clearing up. Albert was killed while in the fire service during World War II.

The printers wrote their names and dates in the fifties but Gary wrote “[here] all the time”

You may also like to read

At W. F. Arber & Co, Printing Works

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKETS

This week I learnt belatedly that my friend Gary Arber – the legendary printer of the Roman Rd – died three years ago. Here is my account of my second visit to his print works at the time I first got to know him.

Before

After

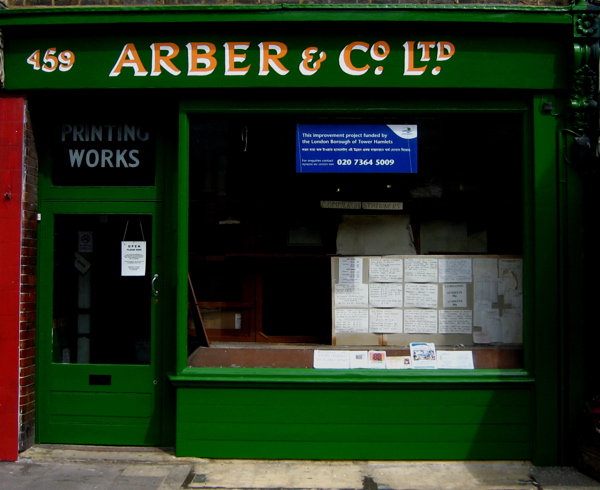

Six months later, there had been changes at W.F.Arber & Co Ltd (the printing works opened by Gary Arber’s grandfather in 1897 in the Roman Rd) since I first visited. At that time, Gary was repairing sash windows on the upper floors, replacing rotten timber and reassembling the frames with superlative skill. Unexpectedly, Gary was the recipient of a small grant from the Olympic fund for the refurbishment of his shop front, which had not seen a lick of new paint since Gary last painted it in 1965.

The contractors were responsible for the fresh coat of green but Gary climbed up a ladder and repainted the elegant lettering himself with a fine brush, delicately tracing the outline of the letters from the originals, just visible through the new paint. This was exactly what he did once before, in 1965, tracing the lettering from its first incarnation in 1947 when the frontage was spruced up to repair damage sustained during the war.

No doubt the Olympic committee could sleep peacefully in their beds, confident that the reputation of our nation would not be brought down by shabby paintwork on the front of W.F.Arber’s Printing Shop, glimpsed by international athletes making their way along the Roman Rd to compete in the Olympics at Stratford in 2012. Equally, Gary was happy with his nifty new paint job and so all parties were pleased with this textbook example of the fulfilment of the ambitious rhetoric of regeneration in East London which the Olympics promised.

If you look closely, you will see that the glass bricks in the pavement had been concreted over. When Gary found they were cracking and there was a risk of some passerby falling eight feet down into the subterranean printing works, he obtained quotes from builders to repair them. Unwilling to pay the price of over five thousand pounds suggested, with astounding initiative Gary did the work himself. He set up a concrete mixer in the basement printing shop, filled the void beneath the glass bricks with rubble, constructed a new wall between the building and the street, and carried all the materials down the narrow wooden cellar stairs in a bucket, alone. Gary’s accomplishments filled me with awe, for his enterprising nature, undaunted resilience and repertoire of skills.

“I shouldn’t be alive,” said Gary with a wry melancholic smile, referring not to his advanced years but to a close encounter with a doodle bug, while walking on his way down the road to school during the war, “The engine cut, which means it was about to explode and I could see it was coming straight for me, but then the wind caught it and blew it to one side. We lost all the glass in the explosion! Another day, my friend David Strudwick and I were eyeballed by the pilots of two Fokker Wolf 190s. We saw them looking down at us but they didn’t fire. – David joined the airforce at the same time I did, he flew Nimrods and died many years later, while making a home run during a cricket match in Devon.”

These thoughts of mortality were a sombre counterpoint to the benign weather at that time. Leading Gary to recall the happy day his father and grandfather walked out of the printing works at dawn one Summer’s morning and, in their enthusiasm for walking, did not stop until they got to Brighton where they caught the train home, having walked sixty miles in approximately twelve hours.

In those days, Gary’s uncles Len and Albert, worked alongside Gary’s father and grandfather in the print shop, when it was a going concern with six printing presses operating at once. Albert was an auxiliary reserve fireman who was killed in the London blitz and never lived to see his baby daughter born. Gary told me how Albert worked as a printer by day and as a fireman every night, until he was buried hastily in the City of London in an eight person grave. “I don’t know when he slept!” added Gary contemplatively. There was no trace of the grave when Gary went back to look for it, but Albert is commemorated by a plaque at the corner of Althelstan Grove and St Stephen’s Rd.

Whenever I had the privilege of speaking with Gary, his conversation always spiralled off in fascinating tangents that coloured my experience of contemporary life, proposing a broad new perspective upon the petty obsessions of the day. My sense of proportion was restored. This was why I found it such a consolation to visit and it led me to understand why Gary never wanted to retire. Each of Gary’s resonant tales served to explain why his printing shop was special, as the location of so much family and professional life, connected intimately to the great events of history, all of which remained present for Gary in this charmed location.

Once Gary became a sole operator, with only one press functional, he began scaling back the printing operations. And I joined him as he was taking down the printing samples from the wall where they had been for over half a century, since somebody pasted them onto some cheap paper as a temporary measure. It was the scrutiny of these printing specimens that occasioned the reminiscences outlined above. Although these few samples comprised the only archive of Arber’s printing works, even these modest scraps of paper had stories to tell, of businesses long gone, because Gary remembered many of the proprietors vividly as his erstwhile customers.

I was fascinated by the letters ADV, indicating the Bethnal Green exchange, which prefixed the telephone numbers on many of these papers. Gary explained this was created when smart people who lived in the big houses in Bow Rd objected to having BET for Bethnal Green – which they thought was rather lower class – on their notepaper. There were letters to the Times and a standoff with the Post Office, until the local schoolmaster worked out that dialling BET was the same as dialling ADV – which might be taken to stand for ‘advance’ indicating a widely-held optimistic belief in progress, which everyone could embrace. So just like Gary’s Olympic paint job, all parties were satisfied and looked to the future with hope.

“Bill Newman of Advance Insulation used to be covered in white asbestos powder. The whole place was like a flour mill! He smoked a fat cigar which we thought was the cause of the cancer that killed him, but later we learnt the truth. The Victoria Box Company closed in the nineteen sixties after a woman had her fingers cut off by a tin pressing machine and the compensation claim shut the company down. Mr Courcha was around in the nineteen fifties, he had a huge lump on his bald head like something out of a comic. We had three generations of Meggs chimney sweeps until the introduction of the smokeless zone finished them off.”

“Sollash made boxes, the factory took up four or five shops in the Hackney Rd but they packed up when Mr Sollash got old. You see that bull on the Bull Hotel notepaper, that was the bull we used on butcher’s bills! ‘Dr.’ means ‘debtor’, it was standard on invoices then.”

“This is a World War II ration card from Osborne the Butcher. Harry Osborne was a German who changed his name during World War I, his son Len ran the business until he retired in the nineteen seventies.”

You may also like to read

So Long, Gary Arber

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKETS

Only this week, have I learnt that my friend Gary Arber – the legendary printer of the Roman Rd – died three years ago. Gary lived a reclusive existence in Romford and, since I had not received any response from my messages, I had assumed that he might have passed but, nevertheless, I am sad to learn that he is gone from the world. Below is my account of how we first met.

I set out early from Spitalfields, crossing the freshly fallen snow in Weavers’ Fields and walking due East until I came to the premises of Arber & Co Ltd at 459 Roman Rd. Once I rang the bell, Gary Arber appeared from the warren of boxes inside, explaining that he did not have much time because he had to do his accounts. So, without delay, I took the photo above and Gary told to me that his grandfather Walter Francis Arber first opened the shop in 1897, as a printer and stationer that also sold toys. The business was continued by Gary’s father who was also called Walter Francis Arber and it is this name that remains on the stationery today.

“I’m here under duress because I’m an airman,” said Gary, explaining that he took over the business, sacrificing his career as a pilot flying Lincoln Bombers when his father died, because his mother relied upon the income of the printing works. “I left the beautiful Air Force forever in 1954,” he revealed wistfully. It is not hard to envisage Gary as a handsome flying ace, he has that charismatically nonchalant professionalism. Gary retains the Air Force moustache over half a century later, so you only have to imagine a flight suit in place of the overall to complete the picture. There is no doubt Gary saw life before he swapped the flight suit for an overall and vanished into the print shop. He was there at Christmas Island in 1946 to witness one of the first nuclear tests, though thankfully Gary was not one of those pilots who flew through the dust cloud to collect samples. “We were guests of the day, watching from a boat, we had bits of dark glass and they told us to shut our eyes when the countdown reached two and open our eyes to look through the glass when it reached minus five – but you saw it through your eyelids. Then you felt the shock, the turbulence and the heat. It was great fun.” Mercifully, Gary appeared to have suffered no ill-effects, still driving daily from his home in Romford.

In those days, Gary’s shop became something of a magnet for artists who loved his old-school letterpress printing but, as a sole operator, Gary only undertook these jobs “under pressure.” “The quality is rubbish,” he said, grabbing a pad of taxi receipts and turning one over to reveal the impress of the type, embossed into the paper – the only way he could get a clear print from the worn type then. “It should be smooth, like a baby’s bottom,” he sighed, running a single finger across the reverse of the page before tossing it back onto the pile. I was concerned upon Gary’s behalf until he disarmed me, “I don’t make any money, I’m just pottering about and enjoying myself!” he confided gleefully. Owning his premises, Gary enjoyed complete security and the freedom to carry on in his own sweet way.

I heard a rumour that the Suffragettes’ handbills were printed there and Gary confirmed this. “My grandmother, Emily Arber, was a friend of Mrs Pankhurst and she wouldn’t let my grandfather charge for the printing. A ferocious woman, she ruled everyone – the women, my grandmother and aunt, ran the toys’ side of the business.” And although the toys side was wrapped up long ago when Gary’s aunt (also called Emily) died, the signs remained everywhere. Lifting your eyes above the suspended fluorescents, you discovered beautifully coloured posters produced by toy manufacturers pasted to the ceiling. “If I removed those the roof would probably collapse!” quipped Gary with a grin. Then, indicating the glass-fronted cases that were used to display dolls, “All the shopfittings are a hundred years old, nothing’s been touched.” he said proudly, and pointed to an enigmatic line with scruffy ends of string hanging down, each carrying more dust than you would have thought possible, “Those bits of string had board games hanging from them once.”

Moving a stack of boxes to one side, Gary uncovered some printing samples for customers to select their preferred options. What a selection! There was a ration card from a butcher round the corner, a dance ticket for December 30th 1939 at Wilmot St School, Bethnal Green, and one for an ATS Social with the helpful text “You will be informed in the event of an air raid,” just in case you got seduced by Glenn Miller and do not hear the siren. There was a crazy humour about these things being there. I turned to confront an advert for a Chopper bicycle portraying a winsome lady with big hair, exhorting me to “Be a trendy shopper.” I turned back to Gary, “This is a shop not a museum,” he said sternly. You could have fooled me.

Aware that I was keeping Gary from his chores, I was on the brink of taking my leave, when Gary confessed that he was no longer in the mood for doing accounts. Instead he took me down to the cellar where six printers worked once. “This is where it used to happen,” he announced with bathos, as we descended the wooden staircase into a subterranean space where six oily black beasts of printing presses crouched, artfully camouflaged beneath a morass of waste paper, old boxes and packets with the occasional antique tin toy, left over from stock, to complete the mix. Here was a printing shop from a century ago, an untidy time capsule – where the twentieth century passed through like a furious whirlwind, demanding printing for the Suffragettes and printing for the Government through two World Wars, and whisking Gary away to Christmas Island to witness a nuclear explosion. And this what was what was left. I was completely overawed at the spectacle, as Gary began removing boxes to reveal more of the machines, enthusiastically explaining their different qualities, capabilities and operating systems. He pointed out the two that were used for the Suffragettes’ handbills and I stood in a moment of silent reverence to register the historical significance of these old hulks, a Wharfdale and a Golding Jobber.

Gary made a beeline for the Heidelberg, the only one that still worked, and began tinkering with the type that he used to print the taxi receipt I saw earlier. This was the heart of it all. I joined him and, standing together in the quiet, we both became absorbed by the magic of the press. Gary was explaining the technical names for the parts of the printer’s pie, when an unexpected wave of emotion overcame me there in this gloomy cellar, on that cold morning in February, up to my ankles in rubbish surrounded by historic printing presses.

I doubt very much that Gary did his accounts that day, but Gary is a sociable man with a generous spirit – even if he strikes an unconvincingly gruff posture occasionally – and if you chose to pay a visit yourself, then it is highly possible that you will have learnt – as I did – about the Roman sarcophagus that was discovered in the Roman Rd, or the woman who was the inspiration for the character of Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion, or Gary’s adventures on steam trains in India, or when Gary was invited to the National Physics Laboratory in the fifties see an early computer, as big as four houses, that could play chess.

One word of caution, “Printers are either highly religious or wicked,” declared Gary, adding “- and I don’t go to church!” with melodramatic irony. So if you decided to go round, you had to be sure to pay Gary due respect by buying something, even if it was only a modest thing. You needed to bear in mind, as you purchased your box of paperclips, that Gary was there under duress – he would rather be flying Lincoln Bombers – and then, once this subterfuge was achieved, it was appropriate to widen the nature of discourse.

You may also like to read about

Marie Lenclos In Columbia Rd

Happy Days on Ezra St

Now the sombre tones of autumn have enfolded us, it is startling to be reminded of the brilliant hues of the long hot summer we have left behind. Marie Lenclos has turned her attention to the maze of streets surrounding Columbia Rd Flower Market in Bethnal Green with their curious and contrasting range of domestic architectures. Her new paintings can be seen in an exhibition presented by Art Friend Gallery at 128 Columbia Rd from 23rd October until 2nd November.

“Columbia Rd is a place I visit on a Sunday morning to suck up the atmosphere. Flowers, plants, people, beigels, and antiques delight, but beyond these fleeting joys my eye catches the beauty of the old brickwork, the immaculate lines of nineteenth century terraces, and the profiles of the twentieth century estates rising high above the rooftops. For my show, I walked around the market and surrounding streets searching for permanence. Lost in my thoughts, I let my eyes guide me towards scenes of calm and respite: the quiet composition of a sixties housing estate, the soft reflections of the park in a sash window, the trees filling the streets and bringing cool shade. I love the bustle of the city but, even more, I enjoy the pause offered when you turn a street corner and catch a glimpse of a sunlit wall. The stillness of houses and buildings creates space for people. That is what I tried to capture in this new collection of paintings.”

– Marie Lenclos

Street Corner On Quilter St

Four Windows on Durrant St

Jesus Green

One Window on Durant St

Back of Columbia Rd

Park Reflections on Quilter St

An Evening in May in Bethnal Green Rd

Durant St in July

Evening Light in Padbury Court

The Light at Midday near Ravenscroft Park

Two Windows on the Boundary Estate

Homes in George Loveless House

Sunny Morning in Arnold Circus

From the Platform in Hoxton Station

Paintings copyright © Marie Lenclos

You my also like to take a look at

Businesses In Bishopsgate, 1892

I am giving an illustrated lecture of Spitalfields & Whitechapel in Old Photographs this Thursday 16th October at 7pm at the Hanbury Hall in Hanbury St, E1 6QR. CLICK HERE TO BOOK TICKETS

A Bishopsgate Trade Directory of one hundred and twenty years ago was recently discovered in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute and the adverts for all the specialist small trades that once gathered there portray a very different kind of commerce to the faceless corporate financial industries in their gleaming blocks which dominate this street today.

St Botolph’s Church & White Hart Tavern, Bishopsgate

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to read about

At James Ince & Sons, Umbrella Makers

Charles Goss’ Bishopsgate Photographs

A Walk With Mavis Bullwinkle

I am giving an illustrated lecture of Spitalfields & Whitechapel in Old Photographs this Thursday 16th October at 7pm at the Hanbury Hall in Hanbury St, E1 6QR. CLICK HERE TO BOOK TICKETS

Mavis Bullwinkle

In Spitalfields, we count ourselves favoured that, apart from her six years enforced exile as an evacuee in Aylesbury during World War Two, Mavis Bullwinkle has shown the good sense to spend her entire life here to become our most senior resident. In this picture, you can see her standing at the door of the church house in Buxton St where her grandfather Richard Pugh lived when he came from North Wales as a lay preacher in 1898 to minister to the people of the East End, and it was here that Mavis’ mother Gwen was born in 1899. I regret that we cannot turn back the wheels of time, so that Richard could step through this door to greet his granddaughter, but the unfortunate reality is that he died of pneumonia in 1905 and left Mavis’ grandmother to bring up seven children alone – an event which created repercussions that resonate to this day for Mavis.

Yet Mavis displayed her characteristic good humour, amplified by her bright red ankle-length raincoat, when I met her outside Christ Church after morning prayers on an especially grey and cloudy morning this week. And it was my privilege to take a stroll around the neighbourhood with Mavis, as she pointed out some of the landmarks on her personal landscape, because after her eighty years, there are few who know Spitalfields as well as Mavis.

Although Mavis remembers Christ Church (or “Spitalfields Church” as she knew it) when her Uncle Albert Pugh was caretaker at during the nineteen thirties, she did not come here regularly until 1951 when her local church All Saints in Buxton St was shut. “I found it very gaunt with all that dark masonry,” she recalled, rolling her eyes dramatically and casting her gaze up to the tall spire looming over us. Then, in 1958, death watch beetle was discovered at Christ Church and this was shut too. “They found it on the Thursday and it was closed by the weekend,” Mavis revealed in a disappointed tone, “My sister Margaret was due to be married on the Saturday and she had to make do with the horrible hall in Hanbury St.”

Already the rain was setting in, so we set off briskly towards the Hanbury Hall and Mavis ameliorated her opinion of the place by the time we got there. “My uncle and his family lived here on the ground floor,” she explained, “the bedroom was on the right of the entrance and the living room and kitchen to left.” Mavis told me there was so much unemployment in the nineteen twenties that young men were encouraged to go to Australia and, eager to relieve the burden on his mother, Albert emigrated at nineteen, only to have an accident in the Outback that left him with a curvature of the spine. On his return, he found it even harder to get work until the rector of Christ Church appointed him caretaker. And when he died young in 1943, leaving a wife and two girls, the Rector arranged for them to have a flat in the market building at the corner of Brushfield St. Mavis taught at the Sunday School here at the Hanbury Hall from 1951 until 1981, while the congregation was in exile, and she stood in the rain looking up at the building in disbelief that so much time could have passed.

Then we set off towards the the north-easterly quarter of Spitalfields, once known as Mile End New Town, to the small web of streets which Mavis counts as home and that remains the focus of her existence. Taking a minor detour down Brick Lane to visit the former Mayfair Cinema – once an Odeon and now Cafe Naz – where Mavis came in her teens with her mother during the nineteen forties, “We didn’t come down here much otherwise,” she admitted with a shrug, “We did our shopping in Whitechapel or Bethnal Green.”

The nature of our odyssey caused Mavis to peer in wonder at her familiar streets. “When you live in a place so long you take it for granted, until it’s not there anymore and then you can’t even remember what was there before.” she confessed as we turned from Brick Lane into Buxton St, approaching Allen Gardens. Before the green field that we know today, Mavis recalls a warren of little streets here surrounding All Saints Church, the centre of her emotional and social universe growing up in Albert Family Dwellings in Deal St. This was the block her grandmother moved into in 1905 and Mavis moved out of in 1979 when it was demolished.

“The Reverend Holdstock used to give wonderful Christmas parties, and I had some of the happiest times of my life in here,” she confided to me as we stood outside the square rectory, one of the few old buildings remaining in the street today. “Around 1913, when my aunt Esther was young, she remembered meeting the cows coming up Buxton St to be milked, each morning as she was on her way to work at a factory in Shoreditch.” Mavis informed me, gesturing back towards the Lane and conjuring an image of the herd. When Mavis’ grandfather died, her Aunt Esther had to give up her training to be a teacher, working first as a nanny in the vicarage and then at a clothing factory. “She never got over it that she never got to be a teacher,” recalled Mavis tenderly, “and when she used to go on about it, I’d remind her that if she’d never gone to work in the factory she’d never have met her husband, Uncle John.”

Then we reached the patch of green where the church of All Saints once stood. “It was a very pretty church, late Victorian,” she told me, “built at the same time as the terraces round here. In those days people wouldn’t live somewhere unless there was a church. It was damaged by the bombing and once, when the rain came in the roof, the vicar made a hole in the floor with his umbrella so that it could drain away.”

From here, we walked down Deal St where Albert Family Dwellings formerly stood on the south corner of Underwood Rd. Only the the iron bollards labelled M. E. N. T. remain today to indicate that this was once Mile End New Town. Yet in Mavis’ mind it all still exists – the Prince of Wales pub on the corner of Buxton St, Davis’ Welsh Dairy on the north corner of Underwood Rd and Mrs Finkelstein’s sweetshop opposite, where for penny you could put your hand in a bran tub and get a little thing to put in your dolls’ house. Standing outside the former entrance of Albert Family Dwellings, Mavis recalled the evening of 2nd September 1939 when she and her sister Margaret were summoned to the school to be evacuated without being told where, and Mavis’ mother went home alone clutching a card with her daughters’ address in Aylesbury. Today, Mavis is probably the only witness to the former life of these streets that still resides in this location and the empty pavements are crowded with memories for her.

Mavis gave up a career in the City in preference to a lower paid job as a secretary at the Royal London Hospital because she wanted to be of service to people, and she worked there for forty years. Her grandfather Richard Pugh, the lay preacher from Wales, would have been proud of Mavis, following his example. The last of the Bullwinkles in Tower Hamlets, she fills with delight to speak of Spitalfields, and more than a century of striving and thriving in her family in this corner of the East End. Out of almost everyone I know, Mavis could most be said to be of this place. With a self-effacing nature, she has shown moral courage and selflessness in her work at the hospital, and in caring for her mother and two aunts until they died at ripe old ages. After more than ninety years, Mavis Bullwinkle knows what it means to live, and we salute her example and applaud her spirit.

Gwen Bullwinkle holds up Mavis in Hanbury St in 1933. “Every time my mother saw this picture, she would say, ‘Fancy taking us outside a pub!'”

Mavis by the War Memorial at Christ Church which her father Alf tended. “He used to grow flowers around it and keep it tidy.”

All Saints Sunday School in 1939 – seven year old Mavis is in the second row on the extreme right and her five year old sister Margaret is on her right.

Mavis outside the former rectory of All Saints Church. “I had some of the happiest times of my life here.”

Mavis & Margaret’s evacuation card, 1939.

Mavis stands on the spot where All Saints Church used to be in Buxton St until 1951.

Spitalfields’ celebrations for the coronation of King George VI, 1937.

Mavis in Vallance Rd outside the house of Quaker philanthropist Mary Hughes, daughter of Thomas Hughes. “Mary Hughes came up to my mother pushing me in a pram in the Whitechapel Rd in 1932 and exclaimed ‘Oh you wonderful mother!’ She was a little old lady dressed in black silk, from the nineteenth century, and my mother pulled away in fear. Only later did she learn who it was.”

You may also like to read my original profile

and

Roy Wild, Van Boy

I am giving an illustrated lecture of Spitalfields & Whitechapel in Old Photographs this Thursday 16th October at 7pm at the Hanbury Hall in Hanbury St, E1 6QR. CLICK HERE TO BOOK TICKETS

Roy looking sharp in the fifties – “I class myself as an Hoxtonite”

The great goodsyard in Bishopsgate is an empty place these days, home to a pop-up shopping mall of sea containers and temporary football pitches, but Roy Wild knew it in its heyday as a busy rail depot teeming with life and he still keeps a model of the Scammell Scarab that he once drove there as a talisman of those lost times.

A vast nineteenth century construction of brick and stone, the old goodsyard housed railway lines on multiple levels and was a major staging point for freight, with deliveries of fresh agricultural produce coming in from East Anglia to be sold in the London wholesale markets and sent out again across the country. Today only the fragmentary Braithwaite arches of 1839 and the exterior wall of the former Bishopsgate Station remain as the hint of the wonders that once were there.

Roy knew it not as the Bishopsgate Goodsyard but in the familiar parlance of railway workers as ‘B Gate,’ and B Gate remains a fabled place for him. By their very nature, railways are places of transition and, for Roy Wild, B Gate won a permanent place in his affections as the location of formative experiences which became his rite of passage into adulthood.

“At first, after I left school at fifteen, I went to work for City Electrical in Hoxton and I was put as mate with a fitter named Sid Greenhill. One of the jobs they took on was helping to build the Crawley new town. We had to get the bus to London Bridge, take the train to East Croydon and change to another near Gatwick Airport – which didn’t really exist yet. It was a schlep at seven o’clock in the morning all through the winter, but I stuck it for eighteen months.

My dad, Andy, was a capstan operator for the London & North Eastern Railway at the Spitalfields Empty Yard in Pedley St off Vallance Rd, so I said to him, ‘Can’t you get a job for me where you work?’ He said, ‘There’s nothing going at the moment but I can get you a place at B Gate.’

In 1953, at sixteen and a half, I started as van boy for Dick Wiley in the cartage department at B Gate. The old drivers had worked with horses, they were known as ‘pair-horse carmen’ or ‘single-horse carmen’ and, in the late forties when the horses were done away with and the depot became mechanised, the men were all called in and given three-wheeled Scammell Scarabs and licences, no driving tests in those days. There was a fleet of two hundred of them at B Gate and although strictly, as van boys, we weren’t allowed to drive, we flew around the depot in them.

Our round was Stoke Newington and we’d be given a ticket which was the number of your container and a delivery note of anything up to twenty-five destinations. Then we’d have lunch at a small goods yard at Manor Rd, Stoke Newington, and in the afternoon we’d do collections, picking up parcels and taking them back to B Gate, from where they’d be delivered by rail around the country.

I decided I wanted to work with George Holman, a driver who was known as ‘Cisco’ on account of his swarthy features which made him look Mexican. He was an East Ender like me, rough and ready, and always larking about. His round was Rotherhithe which meant driving through the tunnel and he was a bit of a lunatic behind the wheel. Each morning after the round, he would drop me off at my mum’s in Northport St for lunch and pick me up again at 2pm. One day, we had to go back through ‘the pipe’ as they called the tunnel in Mile End and he said to me, ‘You take it through the tunnel, you know how it works.’ I was only seventeen but I drove that great big truck through the tunnel without any harm whatsoever.

Next I went to work with Bill Scola, a driver from Bethnal Green – the deep East End. He used to do Billingsgate, Spitalfields, Borough, Covent Garden, Brentford and Nine Elms Markets. Bill was a rascal and I was nineteen by then. We were doing a bit of skullduggery and I was told that the British Transport Police were watching me, so I said to Bill, ‘Things are getting too hot,” and I left it alone completely.

Then, one day we were having breakfast with at least a dozen others at the table, including Sid Green who was in charge of Bishopsgate football team, in the new canteen at B Gate when the British Transport Police came in, pinned my arms against my side and lifted me out of the chair. I was taken across to Commercial St Police Station and charged with larceny. They told me I had been seen lifting goods into the van that weren’t on the parcels sheet, with the intention of taking and selling them. I said I didn’t know what they were talking about. What were they were alleging was a complete fabrication and I had witnesses. What they were accusing me of was impossible because I had just clocked in – my clocking in number was 1917 – and there was a least a dozen witnesses on my side, but nevertheless I was convicted. I look back on it with great regret even now.

I was taken to Newington Butts Quarter Sessions which was the nearest Crown Court and I received six months sentence, even though I had first class character witnesses. I was taken straight to Wormwood Scrubs but kept apart from the inmates as a Young Prisoner. I couldn’t believe it, this was a for a first offence. I was sent to East Church open prison on the Isle of Sheppey and given a third remission off my sentence for good behaviour. It was like a Butlins Holiday Camp and I came home after four months. After that I did a couple of odd jobs, but I was full of regret – because I loved the railway so much and I made so many friends there, and particularly because I had disappointed my dad. That was the end of me and the LNER.

Then I met this guy, Billy Davis, he and Patsy (Patrick) Murphy held up Luton Post Office, but the postmaster grabbed hold of the gun and they shot and killed him, and they both got twenty-five years. He told me he worked for the railway and I asked, ‘Which depot?’ He said, ‘London, Midlands & Scottish Railway in Camden, why don’t you apply?’ So I did, I went along to Camden Town and was interviewed and told them I’d never worked on the railway before. When I started there as a driver, they gave me a brand new Bantam Carrier with a trailer and my round was Spitalfields Market, and I was paid by tonnage. The more weight you pulled onto the weighbridge at the Camden Town LMS depot, the more you earned.

I did it for some time and I always had plenty of fruit to take home to my mum. I got together with the Goods Agent’s secretary, he was the top man in the depot and I was on good terms with him too. I got very friendly, taking her out for more than a year, until one day she told me her boss wanted to see me in his office. He said to me, ‘I’ve got bad news – you never declared you were dismissed by LNER. Our security have run a check and they found it out. It’s gone above my head and I have to let you go. It’s all out of my hands.’ He told me he was sorry to see me go because of the amount of tonnage I brought in which was more than other driver.

I was only there eighteen months. It was the finest time of my life because of the camaraderie with all the other drivers. It was a lovely, lovely job and I made friends that I still have to this day.”

Roy Wild with a model of his beloved Scammell Scarab

Roy with a Scammell Scarab in British Rail livery

Colin O’Brien’s photograph of a Scammell Scarab tipped over on the Clerkenwell Rd, 1953

Roy gets into the cabin of a Scamell Scarab of the kind he used to drive at Bishopsgate Goodsyard

Roy’s father Andy worked as a Capstan Operator at Spitalfields Empty Yard at Pedley St off Vallance Rd

Roy Wild & lifelong pal Derrick Porter, the poet – “I came from Hoxton but he came from Old St”

Bishopsgate Station c. 1900

In its heyday the area of tracks at the goodsyard was known as ‘the field’

Looking west, the abandoned goodsyard after the fire of 1964

Looking east, the abandoned goodsyard after the fire

The kitchens of the canteen at the goodsyard

The space of the former canteen where Roy was arrested by the British Transport Police

Abandoned hydraulic lift for lifting vehicles at Bishopsgate goodsyard

The remains of the records at the Bishopsgate goodsyard

When Roy saw this photograph of the demolished goodsyard, he said, “I wish I could have gone and taken one of those bricks as a souvenir.”

The arch beneath the white tarpaulin was where Roy once drove in and out as a van boy

You may also like to read about