At The Bulmer Brick & Tile Company

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

The kiln

Brick Lane takes its name from the brick works that once filled Spitalfields and I always wondered how it was in those former times. So you can imagine my delight to visit Bulmer Brick & Tile Company in Suffolk, where bricks have been made since 1450, and be granted a glimpse of that lost world.

My guide on this journey through time was Peter Minter who has been making bricks in the traditional way for over seventy years. He began by taking me to the hole in the ground where they dig out the mud and pointing out the strata differentiated in tones of brown and grey. ‘You are looking at the Thames Estuary thirty-six million years,’ he declared with a mild grin of philosophical recognition.

At the lowest level is London clay, deposited in primordial times when the Thames flowed through Suffolk, used to make familiar stock bricks of which most of the capital was constructed in previous centuries. ‘Each of the strata here offer different qualities of clay for different purposes,’ Peter explained as he pointed out dark lines formed of volcanic ash that fell upon the estuary a mere twenty-five million years ago. ‘We have another fifty years of clay at this site,’ he admitted to me in the relaxed tone that is particular to a ninety-year-old brick maker.

“My father, Lawrence Minter, took over this brick works in 1936 when he was thirty-five. It had been here for hundreds of years, with the earliest evidence dating from 1450, and it was a typical local brick works. His uncle, FG Minter, was a builder in London and my father was brought up by him as a surveyor.

Before my father could get established, the war came along and shut the place down. There were thirty-five or thirty-six people working here but a lot got called up and we went down to about six or seven men. We made land drain pipes for the Ministry of Supplies and that was what kept us going. Those men were old or infirm but they kept the skills alive.

I was taught by those skilled men who had been born in the nineteenth century and brought up as brick makers. Without realising, I learnt all the old secrets of brick making but it was only when I knew that this was the direction of my life that I decided I had to save it, and started using the old techniques that had been forgotten rather than the new. This is what makes us unique. I have spent my whole life working here and I probably know more about making bricks than anyone alive. The business has changed and yet it has not changed, because the essence is the same.

When my father reopened after the war, everything was already beginning to change. There was so little trade in brick making that he got into the restoration business. When conservation started to develop, I was the only person in the country who knew how to manufacture bricks in the traditional way. Other people have theories but I am the only one who knows how to do it. There is no-one with our philosophy and the way we go about it.

We start backwards. We look at an old house and its history. We do not think simply of the profit we can make from selling you a brick. We work out why the bricks were made the way they were and how they were made, what techniques were used at that time. When I look at a building, I can tell you everything about its history this way.

In London, they were manufacturing what they called the ‘London Stock,’ the cheapest brick they could produce and they used all sorts of waste material in it as well as clay. They did not think about it lasting but it turned out to be one of the finest bricks of all time. That is what they would have been making in Brick Lane in the seventeenth century.

The clay is the secret because whatever have got beneath your feet is what you have to use, its characteristics dictate what you can make. We are digging out the clay for the next summer, we always do it at the end of September and try to catch the end of the good weather, which we have just done. We want it dry and crumbly, we do not want it compressed into mud. It needs to weather, so the salts and minerals in it liberate into the atmosphere, and you avoid getting salt crystallising upon the finished bricks.

When father was running the brick works, he simply dug the clay out but gradually we have become more precise so now we select layers of clay for different jobs. In his day, you bought a brick from Bulmer – father only did ‘Tudor’ – but now we make bricks specially for each particular job. More and more of our work involves some kind of experimentation. We no longer make generic bricks, everything is specialised now. We make over one hundred and fifty different kinds of bricks in a year. We look at our clay for its degree of plasticity, the grey clay is more plastic whereas yellow clay is more sandy, so we blend the clay as necessary for each order of bricks.

We are currently making around 30,000 bricks for Kensington Palace and another 30,000 for the Tower of London. We have been making bricks for Hampton Court since 1957. For thirty years, we supplied the clay for the moulds at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and the ‘bell bricks’ which were the radius bricks upon which they placed the mould.

Our bricks are laid out to air dry before firing in what are called ‘hack rows’ on the ‘hack ground’ or ‘hack stead.’ These are Saxon words. Once the bricks are dry enough, we set them up in ordered lines which is called ‘skinking.’ We have covers to ensure even drying, by keeping off the sun and the rain. If they get wet, they just turn back to mud.

Once a fortnight, we fire the kiln for three days. Someone has to stay to stoke the fires continuously. I rebuilt one of the kilns myself a few years ago. I have been responsible for the construction of four of these domed-roof kilns. I could not find an expert to tell me how to do it, so I worked out how to do it myself. I did not use a wooden frame for the dome, I built it in concentric circles of bricks so it was self supporting. As a child in 1936, I remembered the original kiln being built and the man looking down through the hole in the roof without any former supporting the dome, so I knew it was possible. He was obviously very proud of what he had built, he took me outside and drew a diagram in the dust with a stick to show me how he had built it. He said, ‘When you want to rebuild it, this is what you do.’

It is a down-draught brick kiln with seven fires around the outside to heat it, the heat is drawn up to the domed roof and down through the bricks to escape through the floor. It reaches about 1200 degrees centigrade and some of the brick lining has turned to glass.

Each aspect of brick making requires different skills and we are continually honing those skills and training new people. It takes five years to train a brick maker. I have two sons in the business here and one of them has two sons, so in time they will be taking over.”

Peter Minter, seventy years a brick maker

Thames mud used for London stock bricks

Making a shaped brick in a wooden mould

Jack has been a brick maker for two years

“He’s coming into quite a good brick maker’

Marking a batch of shaped bricks

Setting the bricks out to dry on the hack ground

Stacking bricks in this way is called ‘skinking’

The hack ground

The rough cut pieces of timber around the kiln that allow smoke to escape are known as ‘skantlings.’

Seven fires heat the kiln

Store for brick moulds

The Bulmer Brick & Tile Company, The Brickfields, Bulmer, Suffolk CO10 7EF

The Secret Gardens Of Spitalfields

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

Gardens in Spitalfields are open for visitors this year on Saturday 10th June from 10am – 4pm. Find details at the website of the National Gardens Scheme. If you are clever you can even fit in my tour of Spitalfields on the same day.

These hidden enclaves of green are entirely concealed from the street by the houses in front and the tall walls that enclose them. If you did not know of the existence of these gardens, you might think Spitalfields was an entirely urban place with barely a leaf in sight, but in fact every terrace conceals a string of verdant little gardens and yards filled with plants and trees that defy the dusty streets beyond.

You may also like to read about

Eva Frankfurther’s Drawings

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

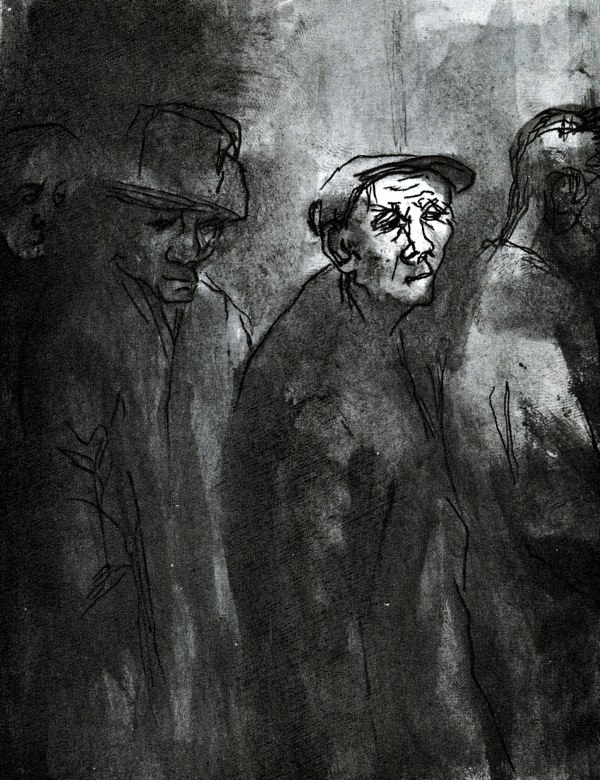

There is an unmistakeable melancholic beauty which characterises Eva Frankfurther‘s East End drawings made during her brief working career in the nineteen-fifties. Born into a cultured Jewish family in Berlin in 1930, she escaped to London with her parents in 1939 and studied at St Martin’s School of Art between 1946 and 1952, where she was a contemporary of Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach.

Yet Eva turned her back on the art school scene and moved to Whitechapel, taking menial jobs at Lyons Corner House and then at a sugar refinery, immersing herself in the community she found there. Taking inspiration from Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz and Picasso, Eva set out to portray the lives of working people with compassion and dignity.

In 1958, afflicted with depression, Eva took her own life aged just twenty-eight, but despite the brevity of her career she revealed a significant talent and a perceptive eye for the soulful quality of her fellow East Enders.

“West Indian, Irish, Cypriot and Pakistani immigrants, English whom the Welfare State had passed by, these were the people amongst whom I lived and made some of my best friends. My colleagues and teachers were painters concerned with form and colour, while to me these were only means to an end – the understanding of and commenting on people.” – Eva Frankfurther

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also wish to take a look at

The Fate Of The White Hart

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

Click here to book for my Spitalfields walk tomorrow and beyond

If you are concerned about the proposed redevelopment of Liverpool St Station – which includes plonking a tower block on top of the grade II listed Great Eastern Hotel – take heed from the pitiful fate of the historic White Hart tavern just across the road. Click here to sign the petition to Save Liverpool St Station

The White Hart (1246-2015)

Charles Goss, one of the first archivists at the Bishopsgate Institute, was in thrall to the romance of old Bishopsgate and in 1930 he wrote a lyrical history of The White Hart, which he believed to be its most ancient tavern – originating as early as 1246. “Its history as an inn can be of little less antiquity than that of the Tabard, the lodging house of the feast-loving Chaucer and the Canterbury pilgrims, or the Boar’s Head in Eastcheap, the rendezvous of Prince Henry and his lewd companions.” – Charles Goss

In Goss’ time, Bishopsgate still contained medieval shambles that were spared by the Fire of London and he recalled the era before the coming of the railway, when the street was lined with old coaching inns, serving as points of departure and arrival for travellers to and from the metropolis. “During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, The White Hart tavern was at the height of its prosperity.” he wrote fondly, “It was a general meeting place of literary men of the neighbourhood and the rendezvous of politicians and traders, and even noblemen visited it.”

The White Hart’s history is interwoven with the founding of the Hospital of St Mary Bethlehem in 1246 by Simon Fitz Mary, whose house once stood upon the site of the tavern. He endowed his land in Bishopsgate, extending beneath the current Liverpool St Station, to the monastery and Goss believed the Brothers stayed in Fitz Mary’s mansion once they first arrived from Palestine, until the hospital was constructed in 1257 with the gatehouse situated where Liverpool St meets Bishopsgate today. This dwelling may have subsequently became a boarding house for pilgrims outside the City gate and when the first licences to sell sweet wines were issued to three taverns in Bishopsgate in August 1365, this is likely to have been the origin of the White Hart’s status as a tavern.

Yet, ten years later in 1375, Edward III took possession of the monastery as an ‘alien priory’ and turned it over to become a hospital for the insane. The gateway was replaced in the reign of Richard II and the date ‘1480’ that adorned the front of the inn until the nineteenth century suggests it was rebuilt with a galleried yard at the same time and renamed The White Hart, acquiring Richard’s badge as its own symbol. The galleried yard offered the opportunity for theatrical performances, while increased traffic in Bishopsgate and the reputation of Shoreditch as a place of entertainments drew the audience.

“Vast numbers of stage coaches, wagons, chaises and carriages passed through Bishopsgate St at this time,” wrote Goss excitedly, “Travellers and carriers arriving near the City after the gates had been closed or those who for other reasons desired to remain outside the City wall until the morning, would naturally put up at one of the galleried inns, or taverns near the City gate and The White Hart was esteemed to be one of the most important taverns at that time. Here they would find small private rooms, where the visitors not only took their meals but transacted all manner of business and, if the food dispensed was good enough, the wine strong, the feather beds deep and heavily curtained, the bedrooms were certainly cold and draughty, for the doors opened onto unprotected galleries – but apparently they were comfortable enough for travellers in former days.”

The occasion of Charles Goss’ history of The White Hart was the centenary of its rebuilding upon its original foundations in 1829, yet although the medieval structure above ground was replaced, Goss was keen to emphasise that, “When the tavern was taken down it was found to be built upon cellars constructed in earlier centuries. Those were not destroyed, but were again used in the construction of the present house.” This rebuilding coincided with Bedlam Gate being removed and the road widened and renamed Liverpool St, after the Hospital of St Mary Bethlehem had transferred to Lambeth in 1815. At this time, the date ‘1246 ‘- referring to the founding of the monastery – was placed upon the pediment on The White Hart where it may be seen to this day.

“This tavern which claims to be endowed with the oldest licence in London, is still popular, for its various compartments appear always to be well patronised during the legal hours they are open for refreshment and there can be none of London’s present-day inns which can trace its history as far back as The White Hart, Bishopsgate,” concluded Goss in satisfaction in 1930.

In 2011, permission was granted by the City of London to demolish all but the facade of The White Hart and in 2015 the pub shut for the last time to permit the construction of a nine storey cylindrical office block of questionable design, developed by Sir Alan Sugar’s company Amsprop. Thus passed The White Hart after more than seven centuries in Bishopsgate, and I am glad Charles Goss was not here to see it.

The White Hart by John Thomas Smith c. 1800

The White Hart from a drawing by George Shepherd, 1810

White Hart Court, where the coaches once drove through to the galleried yard of the White Hart

Design by Inigo Jones for buildings constructed in White Hart Court in 1610

Seventeenth century tavern token, “At The White Hart”

Reverse of the Tavern Token ” At Bedlam Gate 1637″

The White Hart as it appeared in 1787

The White Hart, prior to the rebuilding of 1829

“When the tavern was taken down it was found to be built upon cellars constructed in earlier centuries. Those were not destroyed, but were again used in the construction of the present house.” Charles Goss describing the rebuilding of 1829. These ancient vaults were destroyed in the current redevelopment.

The White Hart in 2015

The White Hart today

Seen from the churchyard of St Botolph’s Bishopsgate by James Gold, 1728

Seen from the south west

Seen from Liverpool St

The meeting of the old and new in Liverpool St

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

Griff Rhys Jones on Liverpool St Station

Towering Folly at Liverpool St Station

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A COPY OF THE CREEPING PLAGUE OF GHASTLY FACADISM

Stephen Hicks, The Boxer Poet

Click here to book for my Spitalfields walk next Saturday and beyond

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

It is my pleasure to publish this account of of the life of Stephen “Johnny” Hicks, the East End boxer-poet, as told in his own words.

“When I turned professional, it was the greatest moment of my life and I meant to make the most of it. On my nineteenth birthday I signed a contract with Harry Abrahams for half-a-dozen ten round bouts at two pounds ten shillings each bout. I lost the first one in seven rounds against Wally Gilbert of Fulham who was a much more experienced boxer, but I won the second with a knock-out over Frankie White of Clerkenwell in the second round.

There have been many famous boxing venues in London’s East End but the most noted of all was the Premierland in Back Church Lane. It was a converted warehouse that held about five thousand spectators and almost every paid boxer of note must have fought there during its nineteen years reign from 1911 to 1930. My own luck at this time seemed to be in. Joe Goodwin of Premierland had billed me up for ten rounds with Alf Sheaf of Customs House. In 1927 I had turned twenty-one and I was in my boxing prime. I had a hard fight with Alf Sheaf and just managed to win on points. It was such a good contest that we had a further two meetings at the same venue, and what’s more I got three pounds for each bout. But all my hopes were shattered in my next bout at Premierland when I met an unknown boxer called Tommy Mason who knocked me out in the first round. I’m glad my brother Albert was not there that night. He would have done his nut I think.

I had a rest from boxing by visiting the hop country in Kent with Albert. We picked hops for a month and got quite bronzed and suntanned. We also kept ourselves fit and well by taking long walks through the countryside. Home again, I found that Joe Goodwin of Premierland had billed me for another ten rounds with former Navy champion “Stoker” Cockerel. He wore black tights and was very unorthodox, but it was great fight which ended in a draw after both of us had taken a count. So I regained my place at Premierland. I had learned one thing about a boxer’s life that if you give the fans their money’s worth you will never be out of a job.

On my next fight at Premierland, I got my first taste of a cauliflower ear. Although it was very painful, I got a piece of boracic lint soaked in surgical spirits and layed it on my ear. I had a stiffener of cardboard handy and bandaged it with the lint to the ear. When going to bed, I had to lay on my ear which was the left one. It was very painful of course, but by the next morning it was back to its normal size, although it was still very tender to the touch and it had to be bathed again in boiling water and in surgical spirits.

Then on Whit Monday in June 1930, when I entered the annual open air featherweight at the Crystal Palace, I received an unlucky blow in my right eye from Harry Brown of Northampton which finished me as a professional boxer. I did not realise how serious it was until the next morning when I paid a visit to the Royal Westminster Ophthalmic Hospital and was treated for a haemorrhage and laid on my back for almost six weeks with both eyes bandaged. They could nothing for me and the sight of my right eye was lost forever. I had a job to keep steady on my feet but my brothers Albert and Jack were with me. I thought, “in boxing I was taught to keep a cool head at all times, so I must try to do this now to fight for my existence.”

Albert and Jack came to my rescue. They had hundreds of tickets printed stating the plight I was in and the cause of it. They were bought by friends, neighbours and supporters, in the docks, shops and local boxing halls. I was very grateful for the money that was brought in, although it seemed I was living on charity I was able to pay my way. As soon as I was fit in mind and body for any kind of labour I turned to the docks, but there were hundreds of other unemployed labourers and so every morning it was a fight to the finish in the scramble to get a day’s work. I actually saw the mounted police with batons raised, disperse the hungry mob whose only criminal offence was a willingness to work.

It was 1936 and I was thirty years of age, when I joined Albert in the blacksmith’s shop. We both had experience beforehand of using a fourteen pound hammer as we once did six weeks work digging roads for the Stepney Borough. It certainly came in handy now as we were using the big hammer eight hours a day. In the summer evenings after work, I used to sit in our backyard at home, where we had grown a garden of mixed flowers, and relax in the thick grass that grew abundantly. Among the animals we had as pets were two cats, two rabbits and a tortoise, I used to get much amusement watching them greet each other by almost touching noses. It seemed so peaceful there and so quiet that I often fell asleep.

I was happy and contented, I could not see the war clouds hovering ever near. My home in Bohn St was bombed but luckily I was not in it at the time. I was thirty-four years of age when, because of my eye, I failed my medical test for military service. I was now living in one small room in John Islip St in Westminster. There were plenty of jobs for everyone, and it was while working on a steel cutting machine in my employer’s yard that I composed my first poem.

I always had the idea I could write poetry, as I had written a few on scraps of paper just for the fun of it. The first poem came to me on the Bridge Wharf in Westminster, when in the corner of the yard I noticed a small white flower growing bravely against a host of weeds and brambles and I thought how wonderful it looked in its struggle for survival. I thought that it must surely win through with such daunting courage, and so the first poem was born.

It was during March 1963 that I bought a ticket for a poetry reading at the Toynbee Hall in Aldgate featuring Dame Sybil Thorndike. I showed her a few of my poems and she said, “They are charming, can I keep them?” It was a week later that I received a letter from the famous actress from her home in Chelsea. “Dear Steve Hicks, Your poems are charming, I read them with great pleasure, thank you so much for giving them to me, all good wishes. Yours sincerely Sybil Thorndike.” One day I entered a poetry competition without success, but then I received a letter from the organiser, who reported that John Betjeman who judged the competition said that, “he hopes I continue to write.” Well of course I did. A defeat to me is nothing, I have had too many of them in the past.”

Copies of Stephen Hicks’ autobiography “Sparring for Luck,”also containing many of his poems, are available from Brick Lane Bookshop.

The Boxer Speaks

I took up boxing just for sport,

and though not very clever

I’m really glad that I was taught

the art of slinging leather.

I was always at my worst

with too many back pedals

And so I started out at first

for cutlery and medals.

So when I learnt to stand my ground

I then began to figure

That I could punch out every round

with all the utmost vigor.

And thus I carried on that way

with very small expense

‘Til I was brimful, one might say,

of much experience.

The big moment was now at hand

and I was mad to go

To get fixed up at Premierland

as an amateur turned pro.

Needless to say, my luck held out,

for there and other shows,

With hard earned cash from every bout

for punches on the nose.

I’ve had black eyes and swelled up ears

and K.O. once or twice

But I enjoyed it through the years

a fighter at cut price.

And through it all I say with pride

most boxers are great pals

Because they will stand by your side

if everyone else fails.

The Boxer Speaks

I took up boxing just for sport,

and though not very clever

I’m really glad that I was taught

the art of slinging leather.

I was always at my worst

with too many back pedals

And so I started out at first

for cutlery and medals.

So when I learnt to stand my ground

I then began to figure

That I could punch out every round

with all the utmost vigor.

And thus I carried on that way

with very small expense

‘Til I was brimful, one might say,

of much experience.

The big moment was now at hand

and I was mad to go

To get fixed up at Premierland

as an amateur turned pro.

Needless to say, my luck held out,

for there and other shows,

With hard earned cash from every bout

for punches on the nose.

I’ve had black eyes and swelled up ears

and K.O. once or twice

But I enjoyed it through the years

a fighter at cut price.

And through it all I say with pride

most boxers are great pals

Because they will stand by your side

if everyone else fails.

Some People

Some people eat and some do not.

It depends on how much cash they’ve got.

So if you’re hungry now I guess

Well, next week you may be getting less.

Some People

Some people eat and some do not.

It depends on how much cash they’ve got.

So if you’re hungry now I guess

Well, next week you may be getting less.

We don’t have much left over After everything is bought, Many are in clover But some don’t get what they ought.

Things that we need throughout the day Are so fantastically dear. It’s all right for them down Pall Mall way But we don’t get much round here.

The toffs of Knightsbridge and Mayfair Are blessed with all good things They’re never short of anything That’s what the good life brings.

I’ve often wondered to myself ‘Why does this have to be?’ For they’ve got nearly all the wealth And there’s nothing for you or me.”

Stephen Hicks (1906-1979) on the cover of his book of poems published in 1974

Stephen Hicks (1906-1979) on the cover of his book of poems published in 1974

Samuel Pepys In Spitalfields

Click here to book for my Spitalfields walk next Saturday and beyond

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

Artist Paul Bommer sent me his sly drawing, envisaging the celebrated diarist’s visit to Spitalfields, three hundred and fifty four years ago this week. At that time, much of Spitalfields was in use as an artillery ground, still commemorated today in the residual names of Artillery Lane, Gun St and the Gun pub.

Tuesday 20th April 1669

“Up and to the Office, and my wife abroad with Mary Batelier, with our own coach, but borrowed Sir J Minnes’s coachman, that so our own might stay at home, to attend at dinner – our family being mightily disordered by our little boy’s falling sick the last night, and we fear it will prove the small-pox.

At noon comes my guest, Mr Hugh May, and with him Sir Henry Capell, my old Lord Capel’s son, and Mr. Parker, and I had a pretty dinner for them, and both before and after dinner had excellent discourse, and shewed them my closet and my Office, and the method of it to their great content, and more extraordinary, manly discourse and opportunity of shewing myself, and learning from others, I have not, in ordinary discourse, had in my life, they being all persons of worth, but especially Sir H. Capell, whose being a Parliament-man, and hearing my discourse in the Parliament-house, hath, as May tells me, given him along desire to know and discourse with me.

In the afternoon, we walked to the Old Artillery-Ground near the Spitalfields, where I never was before, but now, by Captain Deane’s invitation, did go to see his new gun tryed, this being the place where the Officers of the Ordnance do try all their great guns, and when we come, did find that the trial had been made – and they going away with extraordinary report of the proof of his gun, which, from the shortness and bigness, they do call Punchinello. But I desired Colonel Legg to stay and give us a sight of her performance, which he did, and there, in short, against a gun more than twice as long and as heavy again, and charged with as much powder again, she carried the same bullet as strong to the mark, and nearer and above the mark at a point blank than theirs, and is more easily managed, and recoyles no more than that, which is a thing so extraordinary as to be admired for the happiness of his invention, and to the great regret of the old Gunners and Officers of the Ordnance that were there, only Colonel Legg did do her much right in his report of her.

And so, having seen this great and first experiment, we all parted, I seeing my guests into a hackney coach, and myself, with Captain Deane, taking a hackney coach, did go out towards Bow, and went as far as Stratford, and all the way talking of this invention, and he offering me a third of the profit of the invention, which, for aught I know, or do at present think, may prove matter considerable to us – for either the King will give him a reward for it, if he keeps it to himself, or he will give us a patent to make our profit of it – and no doubt but it will be of profit to merchantmen and others, to have guns of the same force at half the charge.

This was our talk – and then to talk of other things, of the Navy in general and, among other things, he did tell me that he do hear how the Duke of Buckingham hath a spite at me, which I knew before, but value it not: and he tells me that Sir T. Allen is not my friend, but for all this I am not much troubled, for I know myself so usefull that, as I believe, they will not part with me; so I thank God my condition is such that I can retire, and be able to live with comfort, though not with abundance.

Thus we spent the evening with extraordinary good discourse, to my great content, and so home to the Office, and there did some business, and then home, where my wife do come home, and I vexed at her staying out so late, but she tells me that she hath been at home with M. Batelier a good while, so I made nothing of it, but to supper and to bed.”

Samuel Pepys (1633-1703)

New illustration copyright © Paul Bommer

You may also like to take a look at

Thomson’s Street Life In London

Click here to book for my Spitalfields walk next Saturday and beyond

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

In Brick Lane, almost everyone carries a camera to capture the street life, whether traders, buskers, street art or hipsters parading fancy outfits. At every corner in Spitalfields, people are snapping. Casual shutterbugs and professional photoshoots abound in a phantasmagoric frenzy of photographic activity.

It all began with photographer John Thomson in 1876 with his monthly magazine Street Life in London, publishing his pictures accompanied by pen portraits by Adolphe Smith as an early attempt to use photojournalism to record the lives of common people. I contemplate the set of Thomson’s lucid pictures preserved at the Bishopsgate Institute, both as an antidote to the surfeit of contemporary imagery and to grant me a perspective on how the street life of London and its photographic manifestation has changed in the intervening years.

For centuries, this subject had been the preserve of popular prints of the Cries of London and, in his photography, Thomson adopted compositions and content that had become familiar archetypes in this tradition – like the chairmender, the sweep and the strawberry seller. Yet although Thomson composed his photographs to create picturesque images, in many cases the subjects themselves take possession of the pictures through the quality of their human presence, aided by Adolphe Smith’s astute texts underlining the harsh social reality of their existence.

When I look at these vivid pictures, I am always startled by the power of the gaze of those who look straight at the lens and connect with us directly, while there is a plangent sadness to those with eyes cast down in subservience, holding an internal focus and lost in time. The instant can be one of frozen enactment, like the billboard men above, demonstrating what they do for the camera, but more interesting to me are the equivocal moments, like the dealer in fancy ware, the porters at Covent Garden and the strawberry seller, where there is human exposure. There is an unresolved tension in these pictures and, even as the camera records a moment of hiatus, we know it is an interruption before a drama resumes – the lost life of more than one hundred and thirty years ago.

The paradoxical achievement of these early street photographs is that they convey a sense the city eludes the camera, because either we are witnessing a tableau which has been composed or there is simply too much activity to be crammed into the frame. As a consequence it is sometimes the “wild” elements beyond the control of the photographer which render these pictures so fascinating – the restless children and disinterested bystanders, among others.

I long to go beyond the bounds of these photographs, both in time and space. And reading Adolphe Smith’s pen portraits, I want to know all these people, because in their photographs they appear monumental in their dignified stillness – as if their phlegmatic attitudes manifest a strength of character and stoicism in the face of a life of hard work.

Street Doctor – “vendors of pills, potions and quack nostrums are not quite so numerous as they were in former days. The increasing number of free hospitals where the poor may consult qualified physicians have tended to sweep this class of street-folks from the thoroughfares of London.”

An Old Clothes Shop, St Giles – “As a rule, secondhand clothes shops are far from distinguished in their cleanliness, and are often the fruitful medium for the propagation of fever, smallpox &c.”

Caney the Clown – “thousands remember how he delighted them with his string of sausages at the yearly pantomime, but Caney has cut his last caper since his exertions to please at Stepney Fair caused the bursting of a varicose vein in his leg and, although his careworn face fails to reflect his natural joviality, the mending of chairs brings him constant employment.”

Dealer in Fancy Ware (termed swag selling) – “it’s not so much the imitation jewels the women are after, it’s the class of jewels that make the imitation lady.”

William Hampton of the London Nomades – “Why what do I want with education? Any chaps of my acquaintance that knows how to write and count proper ain’t much to be trusted into the bargain.”

The Temperance Sweep – “to his newly acquired sobriety, monetary prosperity soon ensued and he is well known throughout the neighbourhood, where he advocates the cause of total abstinence..”

The Water Cart – “my mate, in the same employ, and me, pay a half-a-crown each for one room, washing and cooking. It costs me about twelve shillings a week for my living and the rest I must save, I have laid aside eight pounds this past twelve months.”

Survivors of Street Floods in Lambeth – “As for myself, I have never felt right since that awful night when, with my little girl, I sat above the water on my bed until the tide went down.”

The Independent Bootblack – “the independent bootblack must always carry his box on his shoulders and only put it down when he has secured a customer.”

Itinerant Photographer on Clapham Common – “Many have been tradesmen or owned studios in town but after misfortunes in business or reckless dissipations are reduced to their present more humble avocation.”

Public Disinfectors – “They receive sixpence an hour for disinfecting houses and removing contaminated clothing and furniture, and these are such busy times that they often work twelve hours a day.”

Flying Dustmen – “they obtained their cognomen from their habit of flying from from one district to another. When in danger of collison with an inspector of nuisances, they adroitly change the scene of their labours.”

Cheap Fish of St Giles – ” Little Mic-Mac Gosling, as the boy with the pitcher is familiarly called by all his extended circle of friends and acquaintances, is seventeen years old, though he only reaches to the height of three feet ten inches. His bare feet are not necessarily symptoms of poverty, for as a sailor during a long voyage to South Africa he learnt to dispense with boots while on deck.”

Strawberries, All Ripe! All Ripe! – “Strawberries ain’t like marbles that stand chuckin’ about. They won’t hardly bear to be looked at. When I’ve got to my last dozen baskets, they must be worked off for wot they will fetch. They gets soft and only wants mixin’ with sugar to make jam.”

The Wall-Workers (A system of cheap advertising whereby a wall is covered with an array of placards that are hung up in the morning and taken in at night) – Business, sir! Don’t talk to us of business! It’s going clean away from us.”

Cast-Iron Billy – “forty-three years on the road and more, and but for my rheumatics, I feel almost as hale and hearty as any man could wish .”

Labourers at Covent Garden Market – “it is in the early morning that they congregate in this spot, and they are soon scattered to all parts of the metropolis, laden with plants of every description.”

The London Boardmen – “If they walk on the pavement, the police indignantly throw them off into the gutter, where they become entangled in the wheels of carriages, and where cabs and omnibuses are ruthlessly driven against them.”

Workers on the Silent Highway – “their former prestige has disappeared, the silent highway they navigate is no longer the main thoroughfare of London life and commerce, the smooth pavements of the streets have successfully competed with the placid current of the Thames.”

Old Furniture Seller in Holborn – “As a rule, second-hand furniture men take a hard and uncharitable view of humanity. They are accustomed to the scenes of misery, and the drunkenness and vice, that has led up to the seizure of the furniture that becomes their stock.”

Mush-Fakers and Ginger-Beer Makers. – “the real mush-fakers are men who not only sell but mend umbrellas. By taking the good bits from one old “mushroom” and adding it to another, he is able to make, out of two broken and torn umbrellas, a tolerably stout and serviceable gingham.”

Italian Street Musicans -“there is an element of romance about the swarthy Italian youth to which the English poor cannot aspire.”

A Convicts’ Home – “it is to be regretted that the accompanying photograph does not include one of the released prisoners, but the publication of their portraits might have interfered with their chances of getting employment.”

The Street Locksmith – “there are several devoted to this business along the Whitechapel Rd, and each possesses a sufficient number of keys to open almost every lock in London.”

The Seller of Shellfish – “me and my missus are here at this corner with the barrow in all weathers, ‘specially the missus, as I takes odd jobs beating carpets, cleaning windows, and working round the public houses with my goods. So the old gal has most of the weather to herself.”

The “Crawlers” – “old women reduced by vice and poverty to that degree of wretchedness which destroys even the energy to beg.”

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Read the story of Hookey Alf of Whitechapel from Thomson’s Street Life in London